Hastings

Hastings

Borough of Hastings | |

|---|---|

| Hastings | |

View of Hastings Old Town from the East Hill | |

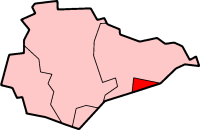

Borough of Hastings shown within East Sussex | |

| Coordinates: 50°51′N 0°34′E / 50.85°N 0.57°E | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | South East England |

| Historic county | Sussex |

| Ceremonial county | East Sussex |

| Status | Non-metropolitan district |

| Government | |

| • MP | Helena Dollimore MP (Labour Co-op) |

| • Mayor | Margarita O'Callaghan |

| • Borough Council | Julia Hilton, Leader (Green) |

| • County Council | Keith Glazier, Leader (Conservative)[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.47 sq mi (29.72 km2) |

| • Rank | 301st (of 296) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 92,855 |

| • Rank | 261st (of 296) |

| • Density | 9,000/sq mi (3,300/km2) |

| Ethnicity (2021) | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021) | |

| • Religion | List

|

| Time zone | UTC0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcodes | |

| Area code | 01424 |

| Website | Hastings Borough Council at www |

Hastings (/ˈheɪstɪŋz/ HAY-stingz) is a seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England, 24 mi (39 km) east of Lewes and 53 mi (85 km) south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place 8 mi (13 km) to the north-west at Senlac Hill in 1066. It later became one of the medieval Cinque Ports. In the 19th century, it was a popular seaside resort, as the railway allowed tourists and visitors to reach the town. Today, Hastings, is a popular seaside resort and is still a fishing port with the UK's largest beach-based fishing fleet. Its estimated population was 91,100 in 2021.[3][4]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The first mention of Hastings is found in the late 8th century in the form Hastingas. This is derived from the Old English tribal name Hæstingas, meaning 'the constituency (followers) of Hæsta'. Symeon of Durham records the victory of Offa in 771 over the Hestingorum gens, that is, "the people of the Hastings tribe." Hastingleigh in Kent was named after that tribe. The place name Hæstingaceaster is found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 1050,[5][6] and may be an alternative name for Hastings. However, the absence of any archaeological remains of or documentary evidence for a Roman fort at Hastings suggest that Hæstingaceaster may refer to a different settlement, most likely that based on the Roman remains at Pevensey.[7]

Evidence of prehistoric settlements have been found at the town site: flint arrowheads and Bronze Age artefacts have been found. Iron Age forts have been excavated on both the East and West Hills. This suggests that the inhabitants moved early to the safety of the valley in between the forts. The settlement was already based on the port when the Romans arrived in Britain for the first time in 55 BC. At this time, they began to exploit the iron (Wealden rocks provide a plentiful supply of the ore), and shipped it out by boat. Iron was worked locally at Beauport Park, to the north of the town. It employed up to one thousand men and is considered to have been the third-largest mine in the Roman Empire.[8] There was also a possible iron-working site near Blacklands Church in the town – the old name of 'Ponbay Bridge' for a bridge that used to exist in the area is a corruption of 'Pond Bay' as suggested by Thomas Ross (Mayor of Hastings and author of an 1835 guide book).[9]

With the departure of the Romans, the town suffered setbacks. The Beauport site was abandoned, and the town suffered from problems from nature and man-made attacks. The Sussex coast has always suffered from occasional violent storms; with the additional hazard of longshore drift (the eastward movement of shingle along the coast), the coastline has frequently changed. The original Roman port is probably now under the sea.[10]

Bulverhythe was probably a harbour used by Danish invaders, which suggests that -hythe or hithe means a port or small haven.[11]

Kingdom of Haestingas

[edit]From the 6th century AD until 771, the people of the area around modern-day Hastings, identified the territory as that of the Haestingas tribe and a kingdom separate from the surrounding kingdoms of Suth Saxe ("South Saxons", i.e. Sussex) and Kent. It worked to retain its separate cultural identity until the 11th century.[12] The kingdom was probably a sub-kingdom, the object of a disputed overlordship by the two powerful neighbouring kingdoms: when King Wihtred of Kent settled a dispute with King Ine of Sussex & Wessex in 694, it is probable that he ceded the overlordship of Haestingas to Ine as part of the treaty.[12][13]

In 771 King Offa of Mercia invaded Southern England, and over the next decade gradually seized control of Sussex and Kent. Symeon of Durham records a battle fought at an unidentified location near Hastings in 771, at which Offa defeated the Haestingas tribe, effectively ending its existence as a separate kingdom. By 790, Offa controlled Hastings effectively enough to confirm grants of land in Hastings to the Abbey of St Denis, in Paris.[14] But, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 1011 relates that Vikings overran "all Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Haestingas", indicating the town was still considered a separate 'county' or province to its neighbours 240 years after Offa's conquest.[15]

During his reign, Athelstan established a royal mint in Hastings in AD 928.[16]

Medieval Hastings

[edit]

The start of the Norman Conquest was the Battle of Hastings, fought on 14 October 1066, although the battle itself took place 6 mi (9.7 km) to the northwest at Senlac Hill. William had landed on the coast between Hastings and Eastbourne at Pevensey. It is thought that the Norman encampment was on the town's outskirts, where there was open ground; a new town was already being built in the valley to the east. That "New Burgh" was founded in 1069 and is mentioned in the Domesday Book as such. William defeated and killed Harold Godwinson, the last Saxon King of England, and destroyed his army, opening England to the Norman conquest.[citation needed]

William ordered a castle to be built at Hastings, probably using the earthworks of the existing Saxon castle.[citation needed]

Hastings was shown as a borough by the time of the Domesday Book (1086); it had also given its name to the Rape of Hastings, one of the six administrative divisions of Sussex. As a borough, Hastings had a corporation consisting of a "bailiff, jurats, and commonalty". By a charter of Elizabeth I in 1589, the bailiff was replaced by a mayor.[17]

Muslim scholar Muhammad al-Idrisi, writing c.1153, described Hastings as "a town of large extent and many inhabitants, flourishing and handsome, having markets, workpeople and rich merchants".[18]

Hastings and the sea

[edit]

By the end of the Saxon period, the port of Hastings had moved eastward near the present town centre in the Priory Stream valley, whose entrance was protected by the White Rock headland (since demolished). It was to be a short stay: Danish attacks and huge floods in 1011 and 1014 motivated the townspeople to relocate to the New Burgh.

In the Middle Ages Hastings became one of the Cinque Ports; Sandwich, Dover and New Romney were the first, followed by Hastings and Hythe then Rye and Winchelsea. At one point 42 towns were directly or indirectly affiliated with the group.

In the 13th century, much of the town and part of Hastings Castle was washed away in the South England flood of February 1287. During a naval campaign of 1339, and again in 1377, the town was raided and burnt by the French, and seems then to have gone into a decline. As a seaport, Hastings' days were finished.

Hastings had suffered over the years from the lack of a natural harbour, and there have been attempts to create a sheltered harbour. Attempts were made to build a stone harbour during the reign of Elizabeth I, but the sea destroyed the foundations in terrible storms. The fishing boats are still stored on and launched from the beach.

Hastings was then just a small fishing settlement, but it was soon discovered that the new taxes on luxury goods could be avoided by smuggling; the town was ideally located for that purpose.[19] Near the castle ruins, on the West Hill, are "St Clement's Caves", partly natural but mainly excavated by hand by smugglers from the soft sandstone. Their trade was to come to an end with the period following the Napoleonic Wars, for the town became one of the most fashionable resorts in Britain, brought about by the assumed health-giving properties of seawater, as well as the local springs and Roman baths. Once this came about, the town expanded, westwards only as there was little space left in the valley.

It was at this time that the elegant Pelham Crescent and Wellington Square were built; other building followed. In the Crescent (designed by architect Joseph Kay) is the classical style church of St Mary in the Castle (its name recalling the old chapel in the castle above) now in use as an arts centre. Building the crescent and church necessitated further cutting away of the castle hill cliffs. Once that move away from the Old Town had begun, it led to the further expansion along the coast, eventually linking up with the new settlement of St Leonards.

Such extensive development needed a large transient workforce. Many of the people coming into Hastings at this time settled on some waste-ground to the west of the main town called the America Ground. This land, originally a shingle spit created by the great storm of 1287, was declared to be Crown Property after an inquiry held at Battle during 1827 and the land was cleared in preparation for the development of this area of land by Patrick Francis Robertson.[20]

Like many coastal towns, the population of Hastings grew significantly as a result of the construction of railway links and the fashionable growth of seaside holidays during the Victorian era. In 1801, its population was a mere 3,175; by 1831, it had reached over ten thousand; by 1891, it was almost sixty thousand.

| Hastings Harbour Act 1890 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the incorporation of Commissioners and for the construction of Harbour Piers and other Works at Hastings in the County of Sussex and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 53 & 54 Vict. c. cxliii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 4 August 1890 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The last harbour project began in 1896, but this also failed when structural problems and rising costs exhausted all the available funds. Today a fractured seawall is all that remains of what might have become a magnificent harbour. In 1897, the foundation stone was laid on a large concrete structure, but there was insufficient money to complete the work and the "Harbour Arm" remains uncompleted. In fact, during World War II, it was partly blown up to discourage possible use by German invasion forces.

Between 1903 and 1919 Fred Judge FRPS photographed many of the town's events and disasters. These included storms, the first tram, visit of the Lord Mayor of London, Hastings Marathon Race and the pier fire of 1917. Many of these images were produced as picture postcards by the British Postcard manufacturer he founded now known as Judges Postcards.

In the 1930s, the town underwent some rejuvenation. Seaside resorts were starting to go out of fashion, Hastings perhaps more than most. The town council set about a huge rebuilding project, among which the promenade was rebuilt, and an Olympic-size bathing pool was erected. The latter, regarded in its day as one of the best open-air swimming and diving complexes in Europe, later became a holiday camp before closing in 1986. It was demolished, but the area is still known by locals as "the Old Bathing Pool".[21]

The 2021 census reported 91,497 inhabitants.

Governance

[edit]

Hastings returned two Members of Parliament (MPs) from the 14th century until 1885, since when it has returned one. Since 1983, it has been part of the parliamentary constituency of Hastings and Rye; the current MP, since July 2024, is Helena Dollimore of the Labour and Co-operative Party. Prior to 1983, the town formed the Hastings parliamentary constituency by itself.

Hastings, it is thought, was a Saxon town before the arrival of the Normans: the Domesday Book refers to a new Borough: as a borough, Hastings had a corporation consisting of a "bailiff, jurats, and commonalty".[10] Its importance was such that it also gave its name to one of the six Rapes or administrative districts of Sussex.

By a Charter of Elizabeth I in 1589 the bailiff was replaced by a mayor, by which time the town's importance was dwindling. In the Georgian era, patronage of such seaside places (such as nearby Brighton) gave it a new lease of life so that, when the time came with the reform of English local government in 1888, Hastings became a County Borough, responsible for all its local services, independent of the surrounding county, then Sussex (East); less than one hundred years later, in 1974, that status was abolished.

Hastings Borough Council is now in the second tier of local government, below East Sussex County Council.

Geography and climate

[edit]

Hastings is situated where the sandstone beds, at the heart of the Weald, known geologically as the Hastings Sands, meet the English Channel, forming tall cliffs to the east of the town. Hastings Old Town is in a sheltered valley between the East Hill and West Hill (on which the remains of the Castle stand). In Victorian times and later the town has spread westwards and northwards, and now forms a single urban centre with the more suburban area of St Leonards-on-Sea to the west. Roads from the Old Town valley lead towards the Victorian area of Clive Vale and the former village of Ore, from which "The Ridge", marking the effective boundary of Hastings, extends north-westwards towards Battle. Beyond Bulverhythe, the western end of Hastings is marked by low-lying land known as Glyne Gap, separating it from Bexhill-on-Sea.

The sandstone cliffs have been the subject of considerable erosion in relatively recent times: much of the Castle was lost to the sea before the present sea defences and promenade were built, and a number of cliff-top houses are in danger of disappearing around the nearby village of Fairlight.

The beach is mainly shingle, although wide areas of sand are uncovered at low tide. The town is generally built upon a series of low hills rising to 500 ft (150 m) above sea level at "The Ridge" before falling back in the river valley further to the north.

There are three Sites of Special Scientific Interest within the borough; Marline Valley Woods, Combe Haven and Hastings Cliffs To Pett Beach. Marline Valley Woods lies within the Ashdown ward of Hastings. It is an ancient woodland of Pedunculate oak—hornbeam which is uncommon nationally. Sussex Wildlife Trust own part of the site.[22] Combe Haven is another site of biological interest, with alluvial meadows, and the largest reed bed in the county, providing habitat for breeding birds. It is in the West St Leonards ward, stretching into the parish of Crowhurst.[23] The final SSSI, Hastings Cliffs to Pett Beach, is within the Ore ward of Hastings, extending into the neighbouring Fairlight and Pett parishes. The site runs along the coast and is of both biological and geological interest. The cliffs hold many fossils and the site has many habitats, including ancient woodland and shingle beaches.[24]

Climate

[edit]As with the rest of the British Isles and Southern England, Hastings experiences a maritime climate with mild summers and mild winters. In terms of the local climate, Hastings is on the eastern edge of what is, on average, the sunniest part of the UK, the stretch of coast from the Isle of Wight southeastern coast Sandown Bay to the Hastings area. Hastings, tied with Eastbourne, recorded the highest duration of sunshine of any month anywhere in the United Kingdom – 384 hours – in July 1911.[25] Temperature extremes since 1960 at Hastings have ranged from 34.7 °C (94.5 °F) in July 2022,[26] down to −9.8 °C (14.4 °F) in January 1987.[27] The Köppen climate classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb" (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[28]

| Climate data for Hastings 1991–2020, extremes 1960– | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.1 (79.0) |

32.3 (90.1) |

34.7 (94.5) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

14.3 (57.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.3 (47.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.8 (14.4) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 79 (3.1) |

56 (2.2) |

45 (1.8) |

45 (1.8) |

45 (1.8) |

49 (1.9) |

52 (2.0) |

60 (2.4) |

60 (2.4) |

88 (3.5) |

93 (3.7) |

95 (3.7) |

767 (30.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 72 | 90 | 136 | 204 | 237 | 240 | 253 | 235 | 174 | 127 | 81 | 65 | 1,914 |

| Source 1: Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute[29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Met Office [1] | |||||||||||||

Neighbourhoods and areas

[edit]Some of the areas and suburbs of Hastings are Ore, St Leonards, Silverhill, West St Leonards, and Hollington. Ore, Silverhill and Hollington were once villages that have since become part of the Hastings conurbation area during rapid growth. The original part of St Leonards was bought by James Burton and laid out by his son, the architect Decimus Burton, in the early 19th century as a new town: a place of elegant houses designed for the well-off. It also included a central public garden, a hotel, an archery, assembly rooms and a church. Today's St Leonards has extended well beyond that original design, although the original town still exists within it.[30]

Demography

[edit]The population of the town in 2001 was 85,029, by 2009 the estimated population was 86,900. Hastings suffers at a disadvantage insofar as growth is concerned because of its restricted situation, lying as it does with the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty to the north. Redevelopment of the area is partly hampered by the split administration of the combined Hastings and Bexhill economic region between Hastings and Rother District councils. There is little space for further large-scale housing and employment growth within the designated boundaries of Hastings, and development on the outskirts is resisted by Rother council whose administrative area surrounds Hastings. Rother has a policy of urban expansion in the area immediately north of Bexhill, but this requires infrastructure improvements by central Governments which have been under discussion for decades.[31] This situation has now become the subject of parliamentary consideration.[32]

Ethnicity

[edit]| Ethnicity | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White: British | 80004 | 94.09 |

| White: Irish | 808 | 0.95 |

| White: Other | 1686 | 1.98 |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | 320 | 0.38 |

| Mixed: White and Black African | 145 | 0.17 |

| Mixed: White and Asian | 361 | 0.42 |

| Mixed: Other | 268 | 0.32 |

| Asian: Indian | 317 | 0.37 |

| Asian: Pakistani | 57 | 0.07 |

| Asian: Bangladeshi | 112 | 0.13 |

| Asian: Other | 143 | 0.17 |

| Black: Caribbean | 184 | 0.22 |

| Black: African | 180 | 0.21 |

| Black: Other | 46 | 0.05 |

| Chinese | 180 | 0.21 |

| Other | 220 | 0.26 |

Ethnicity in 2001[3]

Economy

[edit]

Until the development of tourism, fishing was Hastings' major industry. The fishing fleet, based at the Stade, remains Europe's largest beach-launched fishing fleet and has recently won accreditation for its sustainable methods. The fleet has been based on the same beach, below the cliffs at Hastings, for at least 400, possibly 600, years. Its longevity is attributed to the prolific fishing ground of Rye Bay nearby.[33] Hastings fishing vessels are registered at Rye, and thus bear the letters "RX" (Rye, SusseX).

There are now various industrial estates that lie around the town, mostly on the outskirts, which include engineering, catering, motoring and construction; however, most of the jobs within the Borough are concentrated on health, public services, retail and education. 85% of the firms (in 2005) employed fewer than 10 people; as a consequence the unemployment rate was 3.3% (cf. East Sussex 1.7%). However, qualification levels are similar to the national average: 8.2% of the working-age population have no qualifications while 28% hold degree-level qualifications or higher, compared with 11% and 31% respectively across England.[citation needed]

Shopping and retail

[edit]

Hastings main shopping centre is Priory Meadow Shopping Centre, which was built on the site of the old Central Recreation Ground which played host to some Sussex CCC first-class fixtures, and cricketing royalty such as Dr. W. G. Grace and Sir Don Bradman. The centre houses 56 stores and covers around 420,000 ft2. Further retail areas in the town centre include Queens Road, Wellington Place and Robertson Street.

There are plans to expand the retail area in Hastings, which includes expanding Priory Meadow and creating more retail space as part of the Priory Quarter development. Priory was intended to have a second floor added to part of the retail area, which has not happened yet and so far only office space has been created as part of the Priory Quarter.[35]

Regeneration

[edit]In 2002 the Hastings and Bexhill task force, set up by the South East England Development Agency, was founded to regenerate the local economy, a 10-year programme being set up to tackle the local reliance on public sector employment. The regeneration scheme saw the construction of the University Centre Hastings, (now known as the University of Brighton in Hastings) the new Sussex Coast College campus and construction of the Priory Quarter, which still remains unfinished but now houses Saga offices, bringing 800 new jobs to the area.[36][37]

Culture and community

[edit]Cadets

[edit]Hastings has an Army Cadet Force (ACF) detachment which is part of Sussex ACF. This detachment is based in the old Territorial Army Unit Building on Cinque Ports Way, and is affiliated to PWRR.[38] Hastings also has a Royal Air Force Air Cadet Squadron, 304 (Hastings) Squadron of Sussex Wing RAFAC, based in the same building.[39] The town also has a Sea Cadet squadron, T.S. Hastings. This sits adjacent to the Army and Air Cadet building on the seafront. The site features a climbing wall and other training facilities.[40]

Events

[edit]

Throughout the year many annual events take place in Hastings, the largest of which being the May Day bank holiday weekend, which features a Jack-in-the-Green festival (revived since 1983) and usually falls around 1–3 May,[41] and the culmination of the Maydayrun—tens of thousands of motorcyclists having ridden the A21 to Hastings. The yearly carnival during Old Town Week takes place every August, which includes a week of events around Hastings Old Town, including a Seaboot race, bike race, street party and pram race. In September, there is a month-long arts festival 'Coastal Currents' and a Seafood and Wine Festival. During Hastings Week held each year around 14 October the Hastings Bonfire Society[42] stages a traditional Sussex Bonfire which includes a torchlight procession through the streets, a beach bonfire and firework display. Hastings Pirate Day takes place in July every year. Hastings, as of November 2017, still holds the Guinness World Record for the most pirates in one place.

Other events include the Hastings Beer and Music Festival, held every July on the Oval (Previously Alexandra Park), the Hastings Musical Festival held every March in the White Rock Theatre, the International Composers Festival split between Hastings and Bexhill during August[43] and the Hastings International Chess Congress. There is also a small Wildman event in late January.

Theatre and cinema

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

There are two main theatres in the town, the White Rock Theatre and the Stables Theatre. The White Rock theatre is the venue of the yearly pantomime and throughout the year hosts comedy, dance and music acts. The Stables stages more local productions and acts as an arts exhibition centre. An additional theatre is located in Cambridge Road, the Henry Ward Hall in a space shared with the His Place church in what used to be the Robertson Street United Reformed Church.

There is a small four screen Odeon cinema in the town, located opposite the town hall; however, there are plans to build a new multiplex cinema as part of the Priory Quarter development in the town centre. The town has an independent cinema called the Electric Palace located in the Old Town and a restored cinema in St Leonards called the Kino Teatr. The new luxury 'Sussex Exchange' Cinema, bar and conference venue is situated in St. Leonards.

The Regal cinema and the Cinema de Luxe in Hastings, and the Elite Cinema in St. Leonards, featured in a 1942 legal case, Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver, a leading case heard in the High Court and the Appeal Court, and ultimately resolved in the House of Lords, on the issue of company directors' duty of loyalty to the company they direct.[44]

Museums and art galleries

[edit]

There are three museums in Hastings; the Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, the Hastings Fishermen's Museum and the Shipwreck Museum. The former two mentioned are open for the whole year while the Shipwreck Museum is open only weekends during the winter, but daily for the rest of the year.

The Hastings Museum and Art gallery concentrates mostly on local history and contains exhibits on Grey Owl and John Logie Baird. It also features a Durbar Hall, donated by Lord Brassey; the hall contains displays focusing on the Indian subcontinent and the Brassey Family. The Fishermen's Museum, housed in the former fishermen's church, is dedicated to the fishing industry and maritime history of Hastings. The Shipwreck Museum displays artifacts from wrecks around the area.

The Hastings Contemporary (formerly Jerwood Gallery until 2 July 2019)[45] located in the Stade area of Hastings Old Town is the home for the Jerwood Collection of 20th and 21st century art and a changing contemporary exhibition programme.[46] The project was opposed by many locals who felt that a new art gallery would have been better located elsewhere in the town.[47]

In 2019, following a funding dispute with its sponsor the Jerwood Foundation, the gallery was renamed the Hastings Contemporary.[48]

Parks and open spaces

[edit]There are many parks and open spaces located throughout the town, one of the most popular and largest being Alexandra Park opened in 1882 by the Prince and Princess of Wales. The park contains gardens, open spaces, woods, a bandstand, tennis courts and a café. Other open spaces include White Rock Gardens, West Marina Gardens, St Leonards Gardens, Gensing Gardens, Markwick Gardens, Summerfields Woods, Linton Gardens, Hollington woods, Filsham Valley, Warrior Square, Castle Hill, St Helens Woods and Hastings Country Park.

Local media

[edit]Local news and television programmes is provided by BBC South East and ITV Meridian. Television signals are received from the local TV transmitter.[49]

Hastings's local radio stations are BBC Radio Sussex on 104.5 FM, Heart South on 102.0 FM and More Radio Hastings on 107.8 FM.

Local newspapers are the Hastings Observer and Hastings Independent Press.

Landmarks

[edit]

Hastings Castle was built in 1070 by the Normans, four years after the Norman invasion. It is located on the West Hill, overlooking the town centre and is a Grade I listed building. Little remains of the castle apart from the arch left from the chapel, part of the walls and dungeons. The nearby St. Clements Caves are home to the Smugglers Adventure, which features interactive displays relating to the history of smuggling on the south coast of England.

Hastings Pier can be seen from any part of the seafront in the town. The old pier was opened in 1872, but closed in 2006 following safety concerns from the council. In October 2010, a serious fire burned down most of the buildings on the pier and caused further damage to the structure.[50] However, the pier reopened on 27 April 2016 in modern architectural forms after a £14.2m refurbishment.[51] It won the Stirling Prize of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA)in 2017.[52]

Many church buildings throughout the town are Grade II listed including; Church in the Wood, Blacklands Parish Church, Ebenezer Particular Baptist Chapel, Fishermen's Museum and St Mary Magdalene's Church.

On the seafront at St Leonards is Marine Court, a 1938 block of flats in the Art Deco style that was originally called 'The Ship' due to its style being based on the ocean liner RMS Queen Mary. This block of flats can be seen up to 20 mi (32 km) away on a clear day, from Holywell, in the Meads area of Eastbourne.

An important former landmark was "the Memorial", a clock tower commemorating Albert the Prince Consort which stood for many years at the traffic junction at the town centre, but was demolished following an arson attack in the 1970s.

Transport

[edit]Road

[edit]Hastings urban area (2011 census: includes Bexhill) is by a sizeable margin the most populous area in Britain to have no direct dual-carriageway link to the national motorway network. There are two major roads in Hastings: the A21 trunk road to London; and the A259 coastal road. Both are beset with traffic problems: although the London road, which has to contend with difficult terrain, has had several sections of widening over the past decades there are still many delays. Long-term plans for a much improved A259 east–west route (including a Hastings bypass) were abandoned in the 1990s. A new Hastings-Bexhill Link Road opened in April 2016 known as the A2690 with the hope of reducing traffic congestion along the A259 Bexhill Road. The new link road travels from Queensway in the North of Hastings and joins up to the A259 in Bexhill.[53] Hastings is also linked to Battle via the A2100, the original London road.

The town is served by Stagecoach South East buses on routes that serve the town, and also extend to Bexhill, Eastbourne and Dover as part of The Wave route. Stagecoach also run long distance buses up to Northiam, Hawkhurst, Royal Tunbridge Wells, Ashford and Canterbury.

National Express run service 023 to London.

National rail

[edit]

Hastings has four rail links: two to London, one to Brighton and one to Ashford. Of the London lines, the shorter is the Hastings Line, the former South Eastern Railway (SER) route to Charing Cross via Battle and Tunbridge Wells, which opened in 1852; and the longer is the East Coastway Line, the former London, Brighton & South Coast Railway (LBSCR) route to Victoria via Bexhill, Eastbourne and Lewes. Trains to Brighton also use the East Coastway Line. The Marshlink Line runs via Rye to Ashford where a connection can be made with Eurostar services, and is unelectrified except for the Hastings to Ore segment.

A historic British Rail Class 201 "Thumper" can sometimes be seen on historic runs to and from Hastings.[54]

Hastings is served by two rail companies: Southeastern and Southern. Southeastern services run along the Hastings Line, generally terminating at Hastings, with some peak services extending to Ore; the other lines are served by Southern, with services terminating at Ore or Ashford.

The town currently has four railway stations: from west to east they are West St Leonards, St Leonards Warrior Square, Hastings and Ore; this latter has been proposed to be renamed to Ore Valley.[55] There is also one closed station and one proposed station in the area. West Marina station (on the LBSCR line) was very near West St Leonards (on the SER line) and was closed in 1967. A new station has been proposed at Glyne Gap in Bexhill, which would also serve residents from western Hastings.[55]

Local rail

[edit]

There are two funicular railways, known locally as the West Hill and East Hill Lifts respectively.

The Hastings Miniature Railway operates along the beach from Rock-a-Nore to Marine Parade, and has provided tourist transport since 1948. The railway was considerably restored and re-opened in 2010.

Paths

[edit]The Saxon Shore Way, (a long distance footpath, 163 mi (262 km) in length from Gravesend, Kent traces the Kent and Sussex coast "as it was in Roman times" to Hastings. The National Cycle Network route NCR2 links Dover to St Austell along the south coast, and passes through Hastings.

Historical transport systems

[edit]Turnpike

[edit]In 1753 many prominent Hastings figures – including the major landowners Edward Milward and John Collier – obtained an act of Parliament, the Hastings-Flimwell Turnpike Act, that allowed them to take control of the existing Hastings-London trackway via Battle and Whatlington, as far north as Flimwell,[56] however the first properly recognised turnpike developed in St. Leonards in 1837 when builder James Burton was building his new town of St Leonards. The route of the road is that taken by the A21 today.

Trams and trolleybuses

[edit]

Hastings had a network of trams from 1905 to 1929. The trams ran as far as Bexhill, and were worked by overhead electric wires, except for the stretch along the seafront from Bo-Peep to the Memorial, which was initially worked by the Dolter stud contact system. The Dolter system was replaced by petrol electric trams in 1914 due to safety concerns,[57] but overhead electrification was extended to this section in 1921. Trolleybuses rather than trams were used in the section that included the very narrow High Street, and the entire tram network was replaced by the Hastings trolleybus system in 1928–1929.[58][59]

Maidstone & District bought the Hastings Tramway Company in 1935, but the trolleybuses still carried the "Hastings Tramways" logo until shortly before they were replaced by diesel buses in 1959, following the failure of the "Save our trolleys" campaign.

Education

[edit]Hastings has 18 primary schools, four secondary schools, one further education college and one higher education institution.

The University of Brighton in Hastings offers higher education courses in a range of subjects and currently attracts over 800 students. The university's Hastings campus doubled in size in 2012, with the addition of the new Priory Square building designed by Proctor and Matthews Architects.[60] This is located in the town centre a short distance from the railway station.

Sussex Coast College, formerly called Hastings College, is the town's further education college; it is located at Station Plaza, next to the railway station.

The secondary schools in the town include Ark Alexandra Academy, Hastings Academy and The St Leonards Academy. East Sussex County Council closed three mixed comprehensive schools: Filsham Valley, The Grove and Hillcrest, replacing them with two academy schools; The St Leonards Academy, and The Hastings Academy. The sponsors for the academies are University of Brighton (lead sponsor), British Telecom and East Sussex County Council itself.

Religious buildings

[edit]The most important buildings from the late medieval period are the two churches in the Old Town, St Clement's (probably built after 1377) and All Saints (early 15th century).[61] There is also a mosque, formerly "Mercatoria School" until purchased by the East Sussex Islamic Association. The former Ebenezer Particular Baptist Chapel in the Old Town dates from 1817 and is listed at Grade II.[62] Christ Church, Blacklands (1876) has a complete decorative scheme of Mural, Stained Glass, Mosaic and Wrought Iron from the firm of Hardman's which gives it a ll* listing. When St. Andrew's was demolished in 1970 to make way for a supermarket, a fragment of the decorative scheme there, painted by Robert Noonan (also known as Robert Tressell, author of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists) was rescued and features in the Hastings Museum. The Parish and title were added to Blacklands Church.

Healthcare

[edit]During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries healthcare has been provided in a number of institutions, including the Royal East Sussex Hospital, Hastings, St Leonards and East Sussex Hospital, the Buchanan Hospital and St Helen's Hospital. In 1993 hospital provision was centralised into the Conquest Hospital.

Sport

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Every year the Hastings Half Marathon is held in the town although due to COVID-19 restrictions there was no half marathon that took place in 2020 or 2021. The 13.1 mi (21.1 km) race first took place in 1984 and attracts entrants from all over the country, taking runners on a route encircling the town, starting and finishing by the West Marina Gardens in St Leonards.

Hastings United F.C. is the town's oldest football team, playing in the Premier Division of the Isthmian League. It was founded in 1894 and plays its home games at The Pilot Field, which ground used to be home to two other senior clubs; St Leonards and the original Hastings United which folded in 1985. There are football clubs in Hastings that compete in the East Sussex League, such as Hollington United, St Leonards Social and Rock-a-Nore, playing at local parks and recreation grounds about the town. United attracted sports media headlines, when in 2013 they made it to the third round of the FA Cup for the first time in their history, being the lowest ranked team left in the contest before going out – losing 4–1 to Middlesbrough.

The Central Recreation Ground was one of England's oldest, most scenic and most famous cricket grounds. The first match was played there in 1864 and the last in 1989, after which the site was redeveloped into a shopping centre which opened in 1996.[63] It was particularly popular with touring Australian sides who played 18 matches there.[64] Hastings Priory is the town's largest cricket club, having 4 teams playing competitive, as well as a large junior section. The club's home is at Horntye Park, though it also makes use of the facilities at Ark Alexandra Academy.

ARK Alexandra Academy sees clubs using the school as their base, such as Hastings & Bexhill Rugby Football Club, Hastings Athletic Club and Hastings Priory Cricket Club 3rd and 4th teams.

Founded in 1895 South Saxons Hockey Club is one of the largest sports clubs in Hastings and is the towns only field hockey club. Locally known as 'Saxons' their home ground is the astroturf pitch at Horntye Park Sports Complex. Saxons field nine Saturday teams (4 Mens, 2 Ladies, 2 Boys development and a Girls development team). Saxons also have a thriving junior section who train on a Sunday and play in county 7's tournaments. Saxons Mens 1st XI play in Kent and Sussex Regional Division One and Saxons Ladies 1st XI play in Sussex Ladies League Premier Division.

Hastings Conquerors is an American Football Club, founded in March 2013 by local resident Chris Chillingworth and currently trains at William Parker Sports College. In June 2013 when it became the UK's first Co-Operative run not-for-profit American Football club.[65]

There are many bowling greens in the parks and gardens located about the town; the Hastings Open Bowls Tournament has been held annually in June since 1911 and attracts many entrants country-wide.[66]

Since 1920 Hastings has hosted the Hastings International Chess Congress. The annual event is held over the Christmas period at Horntye Park Sports Complex. A testament to its importance is that every World Champion before Garry Kasparov except Bobby Fischer played at Hastings including Emanuel Lasker (1895), José Raúl Capablanca (1919, 1929/30, 1930/1 and 1934/5), Alexander Alekhine (1922, 1925/6, 1933/4 and 1936/7), Max Euwe (1923/4, 1930/1, 1931/2, 1934/5, 1945/6 and 1949/50), Mikhail Botvinnik (1934/5, 1961/2 and 1966/7), Vasily Smyslov (1954/5, 1962/3 and 1968/9), Mikhail Tal (1963/4), Tigran Petrosian (1977/8), Boris Spassky (1965/6), and Anatoly Karpov (1971/2).

Hastings & St Leonards/Hastings Downs Golf Club (now defunct) was founded in 1893. The club disappeared in the 1950s.[67]

Hastings has hosted the World Crazy Golf Championships since 2003.

Notable people

[edit]- John Logie Baird lived in Hastings in the 1920s where he carried out experiments that led to the transmission of the first television image.[68] Robert Tressell wrote The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists in Hastings between 1906 and 1910.[69]

- Novelist Catherine Cookson lived in the town for many years and began her writing career when she joined the local writing group.[70] There is a blue plaque on her former home at 9–10 Exmouth Place.[71]

- Many notable figures were born, raised, or lived in Hastings, including computer scientist Alan Turing, poet Fiona Pitt-Kethley, actress Gwen Watford, comedian Jo Brand, Madness singer Suggs and Thomas H. Jukes, biologist. Gareth Barry, who holds the record number of appearances in the Premier League, was born in Hastings. Archibald Belaney, the author who worked as Grey Owl, was born in Hastings and lived here for several years.[72][73]

- Harry H Corbett, an actor best known for his role as Harold Steptoe in the BBC sitcom Steptoe and Son, lived in Hastings up until his death in 1982.

- Mark Edwards, a best-selling British fiction writer, grew up in Hastings.

- Anna Brassey, a collector and feminist pioneer of early photography, was based in Hastings until her death in 1887 (she was buried at sea).

- Tom Chaplin, best known as the lead singer of the English pop rock band Keane, was born in Hastings.

- The internationally renowned punk rock band Maid of Ace is from Hastings.

- Martin Honeysett (1943–2015), cartoonist known for his grotesque and biting sketches, lived in Hastings for a number of years.[74]

- Roger Lewis (born 1960), journalist, writer and biographer, author of The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, lives in the town. He suffered a heart attack on the car park at Morrisons supermarket and had to be airlifted to hospital.[75]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]- Shadow of a Man (1956)[76]

- The Canterbury Tales (1972)

- I Want You (1998)

- Grey Owl (1999)

- Some Voices (2000)

- The Final Curtain (2000)

- The Last of the Blonde Bombshells (2000)

- Another Life (2001)

- When I Was 12 (2001)[77]

- Byzantium (2013)

- Drunk on Love (2015)

- The Great Escaper (2023)

Television

[edit]- Buddy (1986)

- Foyle's War (2002–15)[78]

- Roadkill (TV series) (2020)

- Giri/Haji TV series (2019)[79]

- Close to Me (2021)[80]

Twin towns

[edit]Hastings is twinned with:

- Béthune, France[81]

- Oudenaarde, Belgium

- Schwerte, Germany

- Dordrecht, Netherlands

- Hastings, Sierra Leone

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "The Leader and Deputy Leader – Senior Council members". East Sussex County Council. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ a b UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – Hastings Local Authority (E07000062)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Neighbourhood Statistics". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ "UK Largest Cities". The Geographist. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Eilert Ekwall, The Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names, Oxford University Press, 1936.

- ^ Mills, A. D. & Room, Adrian (2002) "A Dictionary of British Place-names", in: Patrick Hanks et al. The Oxford Names Companion, Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-860561-7, pp. 895–1264; p. 1061

- ^ Combes, Pamela; Lyne, Malcolm (1995). "Hastings, Haestingaceaster and Haestingaport: a question of identity" (PDF). Sussex Archaeological Collections. 133: 213–24. doi:10.5284/1086680. ISSN 0143-8204.

- ^ "Beauport Park, East Sussex". OpenLearn. Open University. 22 June 2006. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Historical Hastings Wiki: Iron Working – Historical Hastings Wiki, accessdate: 10 December 2019

- ^ a b Marchant, Rex (1997). Hastings Past. Chichester: Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 1-86077-046-0.

- ^ "Hithe – the definition of Hithe". TheFreeDictionary.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2006. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons – Sussex". Historyfiles.co.uk. 18 September 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 124.

- ^ "S 133". The Electronic Sawyer. 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Key events 771 – 1699". The Hastings Chronicle. 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Challis, Christopher Edgar; I Stewart; NJ Mayhew; GP Dyer; PP Gaspar (1993). "The English and Norman Mints, c. 600–1158". A New History of the Royal Mint. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-24026-0. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ "Hastings | History of Parliament Online". historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ "Al-Idrisi; The Book of Roger The description of L'Angleterre" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Hastings Museum". Smuggling on the Sussex Coast. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Hastings local history Wiki". Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "The Bathing Pool at Hastings and St Leonards". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

- ^ "Natural England – SSSI (Marline Valley Woods)". English Nature. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ "Natural England – SSSI (Combe Haven)". English Nature. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ^ "Natural England – SSSI (Hastings to Pett Cliffs)". English Nature. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ "1911 Sunshine". TORRO. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- ^ "White Rock Gardens Hastings". wow.metoffice.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ "1987 Temperature". TORRO. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012.

- ^ "Hastings, England Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Archived from the original on 19 August 2017.

- ^ "Hastings Climate". KNMI. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Burton's St Leonards". 1066online. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ "Local Development Framework" (PDF). Hastings Online. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ Commons, The Committee Office, House of. "House of Commons – Communities and Local Government Committee – Second Report". Archived from the original on 27 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peak, Steve (1985). Fishermen of Hastings – 200 years of the Hastings Fishing Community.

- ^ "Opening of Lacuna Place set to create jobs for Hastings". Hastings & St. Leonards Observer. 24 September 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Priory Meadow shops to grow". Archived from the original on 3 October 2011.

- ^ Hastings Regeneration Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine SEEDA

- ^ Sea Space finalises plans for next Priory Quarter development Archived 26 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Sea Space

- ^ "Heathfield ACF Home". Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ "304 (Hastings)". RAF Air Cadets. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Home – Sea Cadets Hastings". sea-cadets.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "hastings-jitg". Archived from the original on 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Hastings Borough Bonfire Society". Archived from the original on 2 April 2005.

- ^ Home | Composers Festival Archived 7 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nolan, R., Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver (1942), in Landmark Cases in Equity, accessed 31 October 2023

- ^ "Hastings Contemporary". Hastings Borough Council. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "The Gallery". Jerwood Gallery. 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (12 March 2009). "Jerwood meets a sea of disapproval in Hastings". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014.

- ^ Stephens, Simon (27 March 2019). "Jerwood Gallery to be Renamed and Relaunched". Museum Association. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Hastings (East Sussex, England) Full Freeview transmitter". May 2004.

- ^ "Hastings Pier fire extinguished after four days". BBC News. 8 October 2010. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "Hastings Pier reopening delayed by a year". BBC News. 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ RIBA. "RIBA Stirling Prize 2017". Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Bexhill to Hastings link road – East Sussex County Council". East Sussex County Council. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008.

- ^ Limited, Richard Griffin, for Hastings Diesels. "Hastings Diesels Limited – Home". Archived from the original on 19 August 2005. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "ACCESS TO HASTINGS MULTI-MODAL STUDY (Consultation Report)" (PDF). p. 324. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ "Hastings History Wiki: Turnpike Roads". Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Historical Hastings Wiki: Tram – Historical Hastings Wiki Archived 14 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, accessdate: 14 January 2020

- ^ Robert J Harley, Hastings Tramways. Middleton Press 1993. ISBN 1-873793-18-9.

- ^ Historical Hastings Wiki: Trolleybus – Historical Hastings Wiki Archived 14 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, accessdate: 14 January 2020

- ^ University of Brighton, News. Archived 20 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Brighton.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 October 2013

- ^ Nairn, Ian, and Pevsner, Nikolaus, The Buildings of England: Sussex, Page 119. Penguin, 1965

- ^ Historic England (2007). "Ebenezer Particular Baptist Chapel, Ebenezer Road, Hastings, Hastings, East Sussex (1043527)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Historical Hastings Wiki: Central Cricket Ground – Historical Hastings Wiki Archived 24 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, accessdate: 24 December 2019

- ^ "Central Recreation Ground – England – Cricket Grounds – ESPN Cricinfo". Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

- ^ Brody, Travis (12 January 2015). "The Hastings Conquerors: A New Model for American Football?". The Growth of a Game.

- ^ "Hastings Open Bowls Tournament". Archived from the original on 25 June 2006.

- ^ "Hastings & St Leonards/Hastings Downs Golf Club" Archived 11 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, "Golf's Missing Links".

- ^ "John Logie Baird". Hastings Museum &Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ "Robert Tressell". Hastings Museum & Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ "Catherine Cookson: Her Life (and Husband) – Hastings History". hastingshistory.net. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Plaques, Open. "Catherine Cookson blue plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Simpson, Jeffrey; Ltd, Macmillan Education; Martin, Ged (26 December 2015). The Canadian Guide to Britain, vol 1: England page 129. Macmillan Education UK. ISBN 9781349811434. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Ruffo, Armand Garnet (1996). Grey Owl: The Mystery of Archie Belaney. Coteau Books. ISBN 9781550505337. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "Farewell, Martin Honeysett – you will be sadly missed". hastingsonlinetimes.co.uk. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Hemsley, Andy (27 February 2023). "Hastings man describes how he came back from the dead after collapsing in Morrisons car park". Sussex Express. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Shadow of a Man". Reel Streets. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "When I Was 12 (2001)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Foyle's War". IMDb. 2 February 2003. Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Giri/Haji". IMDb. 10 January 2020.

- ^ Watts, Alex (16 November 2021). "Hastings and St Leonards: See town locations where new TV thriller Close To Me was filmed". hastingsobserver.co.uk. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns [via WaybackMachine.com]". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baines FSA, John Manwaring (1963). Historic Hastings. F J Parsons Ltd.

- Challis, Christopher Edgar; I Stewart; NJ Mayhew; GP Dyer; PP Gaspar (1993). "The English and Norman Mints, c. 600–1158". A New History of the Royal Mint. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-24026-0. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- Combes, Pamela; Lyne, Malcolm (1995). "Hastings, Haestingaceaster and Haestingaport: a question of identity" (PDF). Sussex Archaeological Collections. 133: 213–24. doi:10.5284/1086680. ISSN 0143-8204.

- Peak, Steve (1985). Fishermen of Hastings: 200 Years of the Hastings Fishing Community. Newsbooks. ISBN 0-9510706-0-6.

- Marchant, Rex (1997). Hastings Past. Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 1-86077-046-0.

- Winn, Christopher (2005). I Never Knew That About England.

- Down the Line to Hastings Brian Jewell, The Baton Press ISBN 0-85936-223-X

- Robert J Harley, Hastings Tramways. Middleton Press 1993. ISBN 1-873793-18-9.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Penguin. p. 119.

- Brooks, Ken (1972). Hastings: Then And Now.

External links

[edit]