Juglans nigra

| Eastern black walnut | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leaves and fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Subtribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | J. nigra

|

| Binomial name | |

| Juglans nigra | |

| |

| Natural range of Juglans nigra | |

Juglans nigra, the eastern black walnut, a species of flowering tree in the walnut family, Juglandaceae, is native to eastern North America. It grows mostly in riparian zones, from southern Ontario, west to southeast South Dakota, south to Georgia, northern Florida and southwest to central Texas. Wild trees in the upper Ottawa Valley may be an isolated native population or may have derived from planted trees.

The black walnut is a large deciduous tree attaining heights of 30–40 m (98–131 ft). Under forest competition, it develops a tall, clear trunk; the open-grown form has a short trunk and broad crown. The bark is grey-black and deeply furrowed. The pith of the twigs contains air spaces. The leaves are alternate, 30–60 cm (12–24 in) long, odd-pinnate with 15–23 leaflets, with the largest leaflets located in the center, 7–10 cm long and 2–3 cm broad. The male flowers are in drooping catkins 8–10 cm (3.1–3.9 in) long, the female flowers are terminal, in clusters of two to five, ripening during the autumn into a fruit (nut) with a brownish-green, semifleshy husk and a brown, corrugated nut. The whole fruit, including the husk, falls in October; the seed is relatively small and very hard. The tree tends to crop more heavily in alternate years. Fruiting may begin when the tree is 4–6 years old, however large crops take 20 years. Total lifespan of J. nigra is about 130 years. Black walnut does not leaf out until late spring when the soil has warmed and all frost danger is past. Like other trees of the Fagales order (oaks, hickories, chestnuts, birches, etc.), it has monoecious wind-pollinated catkins. The flowers comprise separate males and females, which do not appear on the same plant at once in order to prevent self-pollination and inbreeding. Thus, two trees are required to produce a seed crop and black walnut readily hybridizes with other members of the Juglans genus.

While its primary native region is the Midwest and east-central United States, the black walnut was introduced into Europe in 1629. It is cultivated there and in North America as a forest tree for its high-quality wood. Black walnut is more resistant to frost than the English or Persian walnut, but thrives best in the warmer regions of fertile, lowland soils with high water tables. Black walnut is primarily a pioneer species similar to red and silver maple and black cherry. It will grow in closed forests, but needs full sun for optimal growth and nut production. Because of this, black walnut is a common weed tree found along roadsides, fields, and forest edges in the eastern US. The wood is used to make furniture, flooring, and rifle stocks, and oil is pressed from the seeds. Nuts are harvested by hand from wild trees. About 65% of the annual wild harvest comes from the U.S. state of Missouri, and the largest processing plant is operated by Hammons Products in Stockton, Missouri. The black walnut nutmeats are used as an ingredient in food, while the hard black walnut shell is used commercially in abrasive cleaning, cosmetics, and oil well drilling and water filtration.

Where the range of J. nigra overlaps that of the Texas black walnut J. microcarpa, the two species sometimes interbreed, producing populations with characteristics intermediate between the two species.[1]

Uses

Black walnut | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nutritional value per 100 grams | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 2,586 kJ (618 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

9.91 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Starch | 0.24 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 1.10 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 6.8 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

59.00 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 3.368 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 15.004 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 35.077 g 2.006 g 33.072 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

24.06 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 4.56 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[2] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Planting

Black walnut plantings can be made to produce timber, nuts, or both timber and nuts. Patented timber-type trees were selected and released from Purdue University in the early 1990s. These trees have been sporadically available from nurseries. Varieties include Purdue #1, which can be used for both timber and nut production, though nut quality is poor compared to varieties selected specifically as nut producers.

Grafted, nut-producing trees are available from several nurseries operating in the U.S. Selections worth considering include Thomas, Neel #1, Thomas Myers, Pounds #2, Stoker, Surprise, Emma K, Sparrow, S127, and McGinnis. Several older varieties, such as Kwik Krop, are still in cultivation; while they make decent nuts, they would not be recommended for commercial planting. A variety index and characteristics guide is available from Missouri Extension.

Pollination requirements should be considered when planting black walnuts. As is typical of many species in Juglandaceae, Juglans nigra trees tend to be dichogamous, i.e.. produce pollen first and then pistillate flowers or else produce pistillate flowers and then pollen. An early pollen-producer should be grouped with other varieties that produce pistillate flowers so all varieties benefit from overlap. Cranz, Thomas, and Neel #1 make a good pollination trio. A similar group for more northern climates would be Sparrow, S127, and Mintle.

J. nigra is also grown as a specimen ornamental tree in parks and large gardens, growing to 30 m (98 ft) tall by 20 m (66 ft) broad.[4] It has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[5]

Food

Black walnut nuts are shelled commercially in the United States. The nutmeats provide a robust, distinctive, natural flavor and crunch as a food ingredient. Popular uses include ice cream, bakery goods and confections. Consumers include black walnuts in traditional treats, such as cakes, cookies, fudge, and pies, during the fall holiday season. The nuts' nutritional profile leads to uses in other foods, such as salads, fish, pork, chicken, vegetables and pasta dishes.

Nutritionally similar to the milder-tasting English walnut, the black walnut kernel is high in unsaturated fat and protein. An analysis of nut oil from five named J. nigra cultivars (Ogden, Sparrow, Baugh, Carter and Thomas) showed the most prevalent fatty acid in J. nigra oil is linoleic acid (27.80–33.34 g/100g dry kernel), followed (in the same units) by oleic acid (14.52–24.40), linolenic acid (1.61–3.23), palmitic acid (1.61–2.15), and stearic acid (1.07–1.69).[6] The oil from the cultivar Carter had the highest mol percentage of linoleate (61.6), linolenate (5.97%), and palmitate (3.98%); the oil from the cultivar Baugh had the highest mol percentage of oleate (42.7%); the oil from the cultivar Ogden has the highest mol percentage of stearate (2.98%).

Tapped in spring, the tree yields a sweet sap that can be drunk or concentrated into syrup or sugar.[citation needed]

Nut processing by hand

The extraction of the kernel from the fruit of the black walnut is difficult. The thick, hard shell is tightly bound by tall ridges to a thick husk. The husk is best removed when green, as the nuts taste better if it is removed then.[citation needed] Rolling the nut underfoot on a hard surface such as a driveway is a common method; commercial huskers use a car tire rotating against a metal mesh. Some take a thick plywood board and drill a nut-sized hole in it (from one to two inches in diameter) and smash the nut through using a hammer. The nut goes through and the husk remains behind.[7]

While the flavor of the Juglans nigra kernel is prized, the difficulty in preparing it may account for the wider popularity and availability of the Persian walnut.

Dye

Black walnut drupes contain juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), plumbagin (yellow quinone pigments), and tannin. These compounds cause walnuts to stain cars, sidewalks, porches, and patios, in addition to the hands of anyone attempting to shell them.[8] The brownish-black dye was used by early American settlers to dye hair.[9][better source needed] According to Eastern Trees in the Petersen Guide series, black walnuts make a yellowish-brown dye, not brownish-black. The apparent confusion is easily explained by the fact that the liquid (dye) obtained from the inner husk becomes increasingly darker over time, as the outer skin darkens from light green to black. Extracts of the outer, soft part of the drupe are still used as a natural dye for handicrafts.[10] The tannins present in walnuts act as a mordant, aiding in the dyeing process,[11][12] and are usable as a dark ink or wood stain.[13]

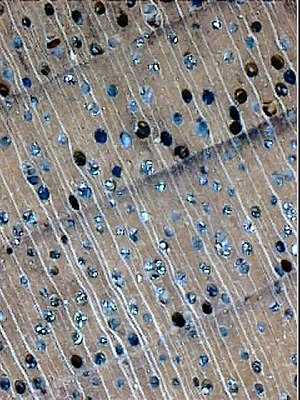

Wood

Black walnut is highly prized for its dark-colored, true heartwood. It is heavy and strong, yet easily split and worked. Walnut wood has historically been used for gunstocks, furniture, flooring, paddles, coffins, and a variety of other wood products. Due to its value, forestry officials often are called on to track down walnut poachers; in 2004, DNA testing was used to solve one such poaching case, involving a 55-foot (16-m) tree worth US$2,500. Black walnut has a density of 660 kg per cubic meter (41.2 lb/cubic foot),[14] which makes it less dense than oak.

Pests

Maggots (larvae of Rhagoletis completa and Rhagoletis suavis) in the husk are common, though more a nuisance than a serious problem for amateurs, who may simply remove the affected husk as soon as infestation is noticed. The maggots develop entirely within the husk, thus the quality of the nutmeat is not affected.[15] However, infestations of maggots are undesirable because they make the husk difficult to remove and are unsightly. Maggots can be serious for commercial walnut growers, who tend to use chemical treatments to prevent damage to the crop.[16] Some organic controls also exist, such as removing and disposing of infested nuts.[17]

The walnut curculio (Conotrachelus retentus) grows to 5 mm long as an adult. The adult sucks plant juices through a snout. The eggs are laid in fruits in the spring and summer. Many nuts are lost due to damage from the larvae, which burrow through the nut shell.[18]

Codling moth (Cydia pomonella) larvae eat walnut kernels, as well as apple and pear seeds.[19]

A disease complex known as thousand cankers disease has been threatening black walnut in several western states.[20] This disease has recently been discovered in Tennessee, and could potentially have devastating effects on the species in the eastern United States.[21] Vectored by the walnut twig beetle (Pityophthorus juglandis), Geosmithia morbida spreads into the wood around the galleries carved by the small beetles. The fungus causes cankers that inhibit the movement of nutrients in black walnut, leading to crown and branch dieback, and ultimately death.[22]

Soil toxicity

Like other walnuts, the roots, nut husks, and leaves secrete a substance into the soil called juglone that is a respiratory inhibitor to some plants. A number of other plants including apples, tomatoes, and white birch are poisoned by juglone, and should not be planted in proximity to a black walnut. Horses are susceptible to laminitis from exposure to black walnut wood in bedding.[23][24]

Alternative medicine

Black walnut has been promoted as a potential cancer cure by alternative medicine practitioners, on the basis it kills a "parasite" responsible for the disease. According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that hulls from black walnuts remove parasites from the intestinal tract or that they are effective in treating cancer or any other disease".[25]

Big tree

The US national champion black walnut is on a residential property in Sauvie Island, Oregon. It is 8 ft 7 in (2.62 m) diameter at breast height and 112 ft (34 m) tall, with a crown spread of 144 feet (44 m).[26]

The largest black walnut in Europe is located in the Castle Park in the city of Sered, Slovakia. It has a circumference of 6.30 m (20.7 ft), height of 25 m (82 ft) and estimated age of 300 years. [27]

Notes

- ^ http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/jugmic/all.html

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ RHS A-Z encyclopedia of garden plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. 2008. p. 1136. ISBN 1405332964.

- ^ "Juglans nigra". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Senter, S. D., Horvat, R. J., and Forbus, W. R.: "GLC-MS Analysis of Fatty Acids From Five Black Walnut Cultivars." Journal of Food Science 47(5) pp 1753, 1755 (1982)

- ^ Mason, Sandra. "Preparing Black Walnuts for Eating". University of Illinois Extension. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ^ Black Walnuts Drug Information

- ^ Nuts with High Fat Content:Black Walnuts

- ^ Black Walnut Basket Dye

- ^ Fixing natural dyes from walnuts, goldenrod, sassafras and poke weed in cotton

- ^ Dyeing with Tannic Acid and Iron: Walnut Husks (2005)

- ^ Making Walnut Ink. Madame Elizabeth de Nevell.

- ^ Niche Timbers Black Walnut

- ^ Walnut Husk Maggot, Rhagoletis suavis (Loew) and Walnut Husk Fly, Rhagoletis completa Cresson

- ^ Walnut Husk Maggot. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

- ^ Walnut Husk Fly.

- ^ Barbara C. Weber, Robert L. Anderson, and William H. Hoffard. How to diagnose black walnut damage. USDA Forest Service. General Technical Report NC-57.

- ^ University of California. Agriculture and Natural Resources. Publication 7412. Codling Moth.

- ^ Purdue University: Purdue Pest & Plant Diagnostic Laboratory. Pest Alert: Walnut Twig Beetle and Thousand Cankers Disease of Black Walnut

- ^ Bill Poovey. Black walnut tree thousand canker first in East US. Times Union. Posted July 30, 2010.

- ^ http://www.clemson.edu/public/regulatory/plant_industry/pest_nursery_programs/invasive_exotic_programs/pest_alerts/walnut_twig_beetle.html

- ^ "Laminitis Caused by Black Walnut Wood Residues" (PDF). Purdue University. January 2005. Retrieved 03-09-2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Black Walnut Toxicity". West Virginia University. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Black Walnut". American Cancer Society. April 2011. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Oregon Big Tree Registry.

- ^ Sered City has a unique tree Juglans nigra tree nominated in the contest of 2012

See also

- English walnut, Persian walnut

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Taxonomy of walnut tree varieties

References

- Hoadley, B. (1990). Identifying Wood: Accurate Results with Simple Tools. Taunton Press. p. 240 pages. ISBN 0-942391-04-7.

- Dirr, M. A. (1998). Manual of Woody Landscape Plants. Stipes Publishing. ISBN 0-87563-795-7

- Petrides, G. A. and Wehr, J. (1998). Eastern Trees. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-90455-2

- Williams, Robert D. Juglans nigra L. In: USDA Forest Service: Silvics of Trees of North America. Volume 2: Hardwoods.

- Little, Elbert L. (1980) National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Eastern Edition. Borzoi Books. ISBN 0-394-50760-6

External links

- USFS: Black Walnut Cultivars

- Guide to "Growing Black Walnuts for Nut Production" University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry

- Walnutsweb.com — extensive information about black walnuts

- Walnut Council.org homepage

- Flora of North America: Juglans nigra—Range distribution Map:

- Bioimages.vanderbilt.edu: Juglans nigra images

- Set of Black Walnut ID photos and range map

- Harvesting Black Walnuts

- Home Production of Black Walnut Nutmeats

- Growing Black Walnut

- Black Walnut crackers

- Black Walnut Diagnostic photos: tree, leaves, bark and fruit

- The Hiker's Notebook

- Black Walnut Toxicity study

- Images, diseases, galls and fungi on treetrees.com

- Juglans

- Edible nuts and seeds

- Trees of Eastern Canada

- Trees of the Eastern United States

- Trees of the Great Lakes region (North America)

- Trees of the Northeastern United States

- Trees of the North-Central United States

- Trees of the Plains-Midwest (United States)

- Trees of the Southeastern United States

- Trees of Ontario

- Flora of the Appalachian Mountains

- Symbols of Missouri

- Trees of humid continental climate

- Plants described in 1753

- Plant dyes

- Garden plants of North America

- Ornamental trees