Korean Americans

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,706,822 0.6% of the US population (2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Los Angeles metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area, Washington, D.C. metropolitan area, and other major American metropolitan areas. | |

| Languages | |

| English, Korean | |

| Religion | |

| 61% Protestantism, 23% Unaffiliated, 10% Roman Catholicism, 6% Buddhism[2][3] |

| Korean Americans | |

| Hangul | 한국계 미국인 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 韓國系美國人 |

| Revised Romanization | Hangukgye Migukin |

| McCune–Reischauer | Han'gukkye Migugin |

Korean Americans (Korean: 한국계 미국인, Hanja: 韓國系美國人, Hangukgye Migukin) are Americans of Korean heritage or descent, mostly from South Korea, with a very small minority from North Korea. The Korean American community comprises about 0.6% of the United States population, or about 1.7 million people, and is the fifth largest Asian American subgroup, after the Chinese American, Filipino American, Indian American, and Vietnamese American communities.[1][4] The U.S. is home to the second largest Korean diaspora community in the world after the People's Republic of China.[5]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 462 | — |

| 1920 | 1,224 | +164.9% |

| 1930 | 1,860 | +52.0% |

| 1940 | 1,711 | −8.0% |

| 1970 | 69,130 | +3940.3% |

| 1980 | 354,593 | +412.9% |

| 1990 | 798,849 | +125.3% |

| 2000 | 1,076,872 | +34.8% |

| 2010 | 1,423,784 | +32.2% |

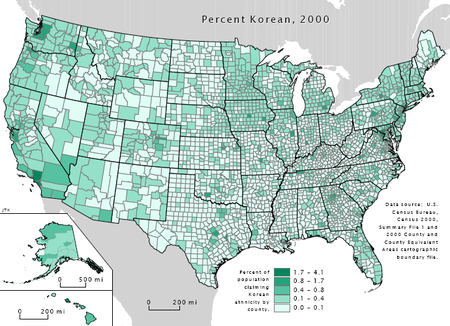

According to the 2010 Census, there were approximately 1.7 million people of Korean descent residing in the United States, making it the country with the second largest Korean population living outside Korea (after the People's Republic of China). The ten states with the largest estimated Korean American populations were California (452,000; 1.2%), New York (141,000, 0.7%), New Jersey (94,000, 1.1%), Virginia (71,000, 0.9%), Texas (68,000, 0.3%), Washington (62,400, 0.9%), Illinois (61,500, 0.5%), Georgia (52,500, 0.5%), Maryland (49,000, 0.8%), and Pennsylvania (41,000, 0.3%). Hawaii was the state with the highest concentration of Korean Americans, at 1.8%, or 23,200 people.

The two metropolitan areas with the highest Korean American populations as per the 2010 Census were the Greater Los Angeles Combined Statistical Area (334,329)[9] and the Greater New York Combined Statistical Area (218,764).[10] The Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan Area ranks third, with approximately 93,000 Korean Americans clustered in Howard and Montgomery Counties in Maryland and Fairfax County in Virginia.[11] Southern California and the New York City metropolitan area[12] have the largest populations of Koreans outside of the Korean Peninsula.[13] Among Korean Americans born in Korea, the Los Angeles metropolitan area had 226,000 as of 2012; New York (including Northern New Jersey) had 153,000 Korean-born Korean Americans; and Washington had 60,000.[14]

The percentage of Korean Americans in Bergen County, New Jersey, in the New York City Metropolitan Area, 6.3% by the 2010 United States Census[15][16] (increased to 6.9% by the 2011 American Community Survey),[17] is the highest of any county in the United States.[16] All of the nation's top ten municipalities by percentage of Korean population as per the 2010 Census are located within Bergen County,[18] while the concentration of Korean Americans in Palisades Park, New Jersey, in Bergen County, is the highest of any municipality in the United States,[19] at 52% of the population.[15] Between 1990 and 2000, Georgia was home to the fastest-growing Korean community in the U.S., growing at a rate of 88.2% over that decade.[20] There is a significant Korean American population in the Atlanta metropolitan area, mainly in Gwinnett County (2.7% Korean), and Fulton County (1.0% Korean).[9]

According to the statistics of the Overseas Korean Foundation and the Republic of Korea's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 107,145 South Korean children were adopted into the United States between 1953-2007.[21]

In a 2005 United States Census Bureau survey, an estimated 432,907 ethnic Koreans in the U.S. were native-born Americans, and 973,780 were foreign-born. Korean Americans that were naturalized citizens numbered at 530,100, while 443,680 Koreans in the U.S. were not American citizens.[22]

While people living in North Korea cannot—except under rare circumstances—leave their country, there are many people of North Korean origin living in the U.S., a substantial portion who fled to the south during the Korean War and later emigrated to the United States. Since the North Korean Human Rights Act of 2004 allowed North Korean defectors to be admitted as refugees, about 130 have settled in the U.S. under that status.[23][24]

History

One of the first Korean Americans was Seo Jae-pil, or Philip Jaisohn, who came to America shortly after participating in an abortive coup with other progressives to institute political reform in 1884. He became a citizen in 1890 and earned a medical degree in 1892 from what is now George Washington University. Throughout his life, he strove to educate Koreans in the ideals of freedom and democracy, and pressed the U.S. government for Korean independence. He died during the Korean War. His home is now a museum, cared for by a social services organization founded in his name in 1975.

A prominent figure among the Korean immigrant community is Ahn Chang Ho, pen name Dosan, a Protestant social activist. He came to the United States in 1902 for education. He founded the Friendship Society in 1903 and the Mutual Assistance Society. He was also a political activist during the Japanese occupation of Korea. There is a memorial built in his honor in downtown Riverside, California and his family home on 36th Place in Los Angeles has been restored by University of Southern California. The City of Los Angeles has also declared the nearby intersection of Jefferson Boulevard and Van Buren Place to be "Dosan Ahn Chang Ho Square" in his honor. The Taekwondo pattern Do-san was named after him.

Another prominent figure among the Korean immigrant community was Syngman Rhee (이승만), a Methodist.[1] He came to the United States in 1904 and earned a bachelor's degree at George Washington University in 1907, a master's degree at Harvard University, and a Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1910. In 1910, he returned to Korea and became a political activist. He later became the first president of the Republic of Korea.

In 1903, the first group of Korean laborers came to Hawaii on January 13, now known annually as Korean-American Day,[25] to fill in gaps created by problems with Chinese and Japanese laborers. Between 1904 and 1907 about 1,000 Koreans entered the mainland from Hawaii through San Francisco.[26] Many Koreans dispersed along the Pacific Coast as farm workers or as wage laborers in mining companies and as section hands on the railroads. Picture brides became a common practice for marriage to Korean men.

After the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910, Korean migration to the United States was virtually halted. The Immigration Act of 1924 or sometimes referred to as the Oriental Exclusion Act was part of a measured system excluding Korean immigrants into the US. In 1952 with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, opportunities were more open to Asian Americans, enabling Korean Americans to move out of enclaves into middle-class neighborhoods. When the Korean War ended in 1953, small numbers of students and professionals entered the United States. A larger group of immigrants included Western princesses married with U.S. servicemen. With the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, Koreans became one of the fastest growing Asian groups in the United States, surpassed only by Filipinos.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the quota system that had restricted the numbers of Asians allowed to enter the United States. Large numbers of Koreans, including some from North Korea who had come via South Korea, have been immigrating ever since, putting Korea in the top six countries of origin of immigrants to the United States[27] since 1975. The reasons for immigration are many including the desire for increased freedom and the hope for better economic opportunities.

In the 1980s and 1990s Koreans became noted not only for starting small businesses such as dry cleaners or convenience stores, but also for diligently planting churches. They would venture into abandoned cities and start up businesses which happened to be predominantly African American in demographics. This would sometimes lead to publicized tensions with customers as dramatized in movies such as Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing, and the Los Angeles riots of April 1992.

Their children, along with those of other Asian Americans, would also be noted in headlines and magazine covers in the 1980s for their numbers in prestigious universities and highly skilled white collar professions. Favorable socioeconomic status and education have led to the painting of Asian groups such as the Koreans as a "model minority". Throughout the 1980s until today, Korean Americans and other East Asian groups continue to attend prestigious universities in high numbers and make up a large percentage of the professional white collar work force including such fields as medicine, law, computer science, finance, and investment banking.

Los Angeles has emerged as a major center of the Korean American community. Its "Koreatown" is often seen as the "overseas Korean capital." It experienced rapid transition in the 1990s, with heavy investment by Korean banks and corporations, and the arrival of tens of thousands of Koreans, as well as even larger numbers of Hispanics.[28][29] Many entrepreneurs opened small businesses, and were hard hit by the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[30] More recently, L.A.'s Koreatown has been perceived to have experienced declining political power secondary to re-districting[31] and an increased crime rate,[32] prompting an exodus of Koreans from the area. Furthermore, the aftermath of the 1992 riots witnessed a large number of Koreans from Southern California moving to the San Francisco Bay Area and opening businesses and buying property near downtown Oakland, furthering the growth of that city's Koreatown until the early 2000s,[33] although this Oakland neighborhood has also subsequently witnessed a decline in its Korean population, created by an exodus to other parts of the Bay Area.

According to Park (1998) the violence against Korean Americans in 1992 stimulated a new wave of political activism among Korean Americans, but it also split them into two main camps. The "liberals" sought to unite with other minorities in Los Angeles to fight against racial oppression and scapegoating. The "conservatives," emphasized law and order and generally favored the economic and social policies of the Republican Party. The conservatives tended to emphasize the political differences between Koreans and other minorities, specifically blacks and Hispanics.[34] Abelmann and Lie, (1997) report that the most profound result was the politicization of Korean Americans, all across the U.S. The younger generation especially realized they had been too uninvolved in American politics, and the riot shifted their political attention from South Korea to conditions in the United States.[35]

In recent years, ethnic Koreans such as Korean Mexicans and Korean Brazilians emigrated to the United States, bringing further diversity to the Korean-American community.

A substantial number of affluent Korean American professionals have settled in Bergen County, New Jersey since the early 2000s (decade) and have founded various academically and communally supportive organizations, including the Korean Parent Partnership Organization at the Bergen County Academies magnet high school[36] and The Korean-American Association of New Jersey.[37] Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, New Jersey, within Bergen County, has undertaken an ambitious effort to provide comprehensive health care services to underinsured and uninsured Korean patients from a wide area with its growing Korean Medical Program, drawing over 1,500 Korean American patients to its annual health festival.[38][39][40][41] Bergen County's Broad Avenue Koreatown in Palisades Park[42] has emerged as a dominant nexus of Korean American culture,[43] and its Senior Citizens Center provides a popular gathering place where even Korean grandmothers were noted to follow the dance trend of the worldwide viral hit Gangnam Style by South Korean "K-pop" rapper Psy in September 2012;[44] while the nearby Fort Lee Koreatown is also emerging as such. The Chusok Korean Thanksgiving harvest festival has become an annual tradition in Bergen County, attended by several tens of thousands.[45]

Bergen County's growing Korean community[46][47][48][49] was cited by county executive Kathleen Donovan in the context of Hackensack, New Jersey attorney Jae Y. Kim's appointment to Central Municipal Court judgeship in January 2011.[50] Subsequently in January 2012, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie nominated attorney Phillip Kwon of Bergen County for New Jersey Supreme Court justice,[51][52][53] although this nomination was rejected by the state's Senate Judiciary Committee,[54] and in July 2012, Kwon was appointed instead as deputy general counsel of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[55] According to The Record of Bergen County, the U.S. Census Bureau has determined the county’s Korean American population – 2010 census figures put it at 56,773[56][57] (increasing to 63,247 by the 2011 American Community Survey)[58] - has grown enough to warrant language assistance during elections,[15] and Bergen County's Koreans have earned significant political respect.[59][60][61] As of May 2014, Korean Americans had garnered at least four borough council seats in Bergen County.[62]

Flatbush boycott

In 1990, Korean-American owned shops were boycotted in the Flatbush section of the borough of Brooklyn in New York City. The boycott started by Black Nationalist, Sonny Carson, lasted for six months and became known as the Flatbush boycott.

Comfort women controversy

In May 2012, officials in Bergen County's borough of Palisades Park, New Jersey rejected requests by two diplomatic delegations from Japan to remove a small monument from a public park, a brass plaque on a block of stone, dedicated in 2010 to the memory of comfort women, thousands of women, many Korean, who were forced into prostitution by Japanese soldiers during World War II.[46][63] Days later, a South Korean delegation endorsed the borough's decision.[64] However, in neighboring Fort Lee, various Korean American groups could not reach consensus on the design and wording for such a monument as of early April 2013.[65][66] In October 2012, a similar memorial was announced in nearby Hackensack, to be raised behind the Bergen County Courthouse, alongside memorials to the Holocaust, the Irish Potato Famine, and the Armenian Genocide,[60] and was unveiled in March 2013.[67][68] An apology and monetary compensation of roughly US$8 million by Japan to South Korea in December 2015 for these transgressions largely fell flat in Bergen County, where the first U.S. monument to pay respects to comfort women was erected.[69]

East Sea controversy

According to The Record, the Korean-American Association of New Jersey petitioned Bergen County school officials in 2013 to use textbooks that refer to the Sea of Japan as the East Sea as well.[70] In February 2014, Bergen County lawmakers announced legislative efforts to include the name East Sea in future New Jersey school textbooks.[71][72] In April 2014, a bill to recognize references to the Sea of Japan also as the East Sea in Virginia textbooks was signed into law.[73]

Sewol ferry tragedy memorial in the United States

In May 2014, the Palisades Park Public Library in New Jersey created a memorial dedicated to the victims of the tragic sinking of the Sewol ferry off the South Korean coast on April 16, 2014.[74]

Nail salon abuse

According to an investigation by The New York Times in 2015, abuse by Korean nail salon owners in New York City and Long Island was rampant, with 70 to 80% of nail salon owners in New York being Korean, per the Korean American Nail Salon Association; with the growth and concentration in the number of salons in New York City far outstripping the remainder of the United States since 2000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Abuses routinely included underpayment and non-payment to employees for services rendered, exacting poor working conditions, and stratifying pay scales and working conditions for Korean employees above non-Koreans.[75]

Languages

Korean Americans can speak a combination of English and Korean depending on where they were born and when they immigrated to the United States. New immigrants often use a mixture of Korean and English, a practice also known as "code switching".[76]

Memorials and celebrities

A number of U.S. states have declared January 13 as Korean American Day in order to recognize Korean Americans' impact and contributions. Celebrities are named at List of Korean Americans.

Politics

In a poll from the Asia Times before the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election, Korean Americans narrowly favored Republican candidate George W. Bush by a 41% to 38% margin over Democrat John Kerry, with the remaining 19% undecided or voting for other candidates.[77] However, according to a poll done by the AALDEF the majority of Korean Americans that voted in the 2004 Presidential Election favored Democrat John Kerry by a 66% to 33% margin over Republican candidate George W. Bush.[78] And another poll done by the AALDEF suggest the majority of Korean Americans that voted in the 2008 Presidential Election favored Democrat Barack Obama by a 64% to 35% margin over Republican John McCain[78] In the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election, Korean Americans favored Democrat Barack Obama over Republican John McCain, around 59% to 41%.[79] However, there are still more registered Republican Korean Americans than registered Democrats. Korean-Americans, due to their Republican and Christian leanings, overwhelmingly supported California's constitutional gay marriage ban, Proposition 8.[80] According to a Multilingual Exit poll from the 2012 Election, 77% of Korean Americans voted for Democrat Barack Obama while only 20% voted for Republican Mitt Romney[81] The poll also showed that 60% of Korean Americans identify themselves as being Democrats, while only 14% of Korean Americans identify themselves as being Republican.[81]

On 12 May 2013, South Korean President Park Geun-hye apologized to a Korean American female intern and Korean community about Yoon Chang-jung US sex scandal during her first trip to the United States as a newly elected president.[82][83]

Religion

Korean Americans have historically had a very strong Christian - particularly Protestant - heritage. Between 70% and 80% identify as Christian; 40% of those consist of immigrants who were not Christians at the time of their arrival in the United States. There are about 4,000 Korean Christian churches in the United States. The Korean Presbyterian churches represent a large religious bodies, the Korean-American Presbyterian Church, the Korean Presbyterian Church in America,[84] the Korean Presbyterian Church in America (Koshin) (part of the Presbyterian Church in Korea (Koshin)).[85] But the majority of Korean Presbyterians are members of the PC(USA) and the Presbyterian Church in America, both have several Korean language Presbyteries across the country.[86]

There are only 89 Korean Buddhist temples in the United States; the largest such temple, Los Angeles' Sa Chal Temple, was established in 1974.[87] A small minority, about 2 to 10% of Korean Americans are Buddhist.[88] Reasons given for the conversion of immigrant Korean families to Christianity include the responsiveness of Christian churches to immigrant needs as well as their communal nature, whereas Buddhist temples foster individual spirituality and practice and provide fewer social networking and business opportunities, as well as social pressure from other Koreans to convert.[89] Most Korean American Christians do not practice traditional Confucian ancestral rites practiced in Korea (in Korea, most Catholics, Buddhists, and nonbelievers practice these rites).[88][90]

Cuisine

"Korean American cuisine" can be described as a fusion of traditional Korean cuisine with American culture and tastes.[91] Dishes such as "Korean tacos" have emerged from the contacts between Korean bodega owners and their Mexican workers in the Los Angeles area, spreading from one food truck (Kogi Korean BBQ) in November 2008 to the national stage eighteen months later.[92]

According to Chef Roy Choi (of Kogi Korean BBQ fame), sundubu jjigae was a dish developed by Korean immigrants in Los Angeles.

Often, chefs borrow from Korean flavors and preparation techniques that they will integrate it into the style they are most comfortable with (whether it be Tex-Mex, Chinese, or purely American). Even a classic staple of the American diet, the hamburger, is available with a Korean twist – bulgogi (Korean BBQ) burgers.

With the popularity of cooking and culinary sampling, chefs, housewives, food junkies, and culinary aficionados have been bolder in their choices, favoring more unique, specialty, and ethnic dishes. Already popular in its subset populations peppered throughout the United States, Korean food debuted in the many Koreatowns found in metropolitan areas including in Los Angeles; Queens and Manhattan in New York City; Palisades Park[93] and Fort Lee[94][95] in Bergen County, New Jersey; Annandale, Virginia; Philadelphia; Atlanta; Dallas; and Chicago. Korean cuisine has unique and bold flavors, colors, and styles; these include spicy oddities (kimchi, kaktugi, sam jang), long fermented pastes (gochujang, ganjang, doenjang), noodle dishes (ramen and naengmyun), and fish cakes and raw seafood concoctions (raw octopus tentacles in spicy sauce, freshly halved sea urchin).

Broad Avenue in Bergen County's Palisades Park Koreatown in New Jersey has evolved into a Korean dessert destination as well;[96][97] while a five-mile long "Kimchi Belt" has emerged in the Long Island Koreatown.[98]

Korean coffeehouse chain Caffe Bene, also serving misugaru, has attracted Korean American entrepreneurs as franchisees to launch its initial expansion into the United States, starting with Bergen County, New Jersey and the New York City Metropolitan Area.[99]

Illegal immigration

In 2009, the Department of Homeland Security estimated that there were two hundred thousand (200,000) Korean "unauthorized immigrants"; they are the sixth largest nationality (tied with Asian Indians) of illegal immigrants behind those from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the Philippines.[100]

Notable Americans of Korean descent

See also

- Asian American

- Demographics of the United States

- Greater Dallas Korean American Chamber of Commerce

- KoreAm

- Korean adoptees

- Korean American writers

- Korean-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce

- Korean Americans in New York City

- Korean diaspora

- Koreans

- Koreatown

- Koreatown, Fort Lee

- Koreatown, Long Island

- Koreatown, Los Angeles

- Koreatown, Manhattan

- Koreatown, Palisades Park

- Koreatown, Philadelphia

- List of Korea-related topics

- List of Korean Americans

References

- ^ a b "Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ POLL July 19, 2012 (2012-07-19). "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". Pew Forum. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pew Forum - Korean Americans' Religions". Projects.pewforum.org. 2012-07-18. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ Barnes, Jessica S.; Bennett, Claudette E. (February 2002), The Asian Population: 2000 (PDF), U.S. Census 2000, U.S. Department of Commerce, retrieved 2009-09-30

- ^ [[:Template:Asiantitle]], South Korea: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2009, retrieved 2009-05-21

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Illinois' 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States". Census.gov. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ "America's Asian Population Patterns 2000-2010". Proximityone.com. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ a b "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data Los Angeles-Long Beach-Riverside, CA CSA". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data New York-Newark-Bridgeport, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ^ "KTV Plus Key Points" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- ^ Chi-Hoon Kim (2015). "Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover's Companion to New York City: A Food Lover's..." Oxford University Press, Google Books. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ Pyong Gap Min (2006). Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues. SAGE Publications. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-4129-0556-5.

Ahn, Daniel. "Profiling Culture: An Examination of Korean American Gangbangers in Southern California". Asian American Law Journal. 11. University of California Berkeley School of Law. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

Charles K. Armstrong (22 August 2013). The Koreas. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-136-16132-2.

Rough Guides (2 May 2011). The Rough Guide to California. Penguin. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4053-8302-8. - ^ Jie Zong and Jeanne Batalova (December 3, 2014). "Korean Immigrants in the United States - Table 1. Top Concentrations by Metropolitan Area for the Foreign Born from Korea, 2008-12". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c Karen Sudol and Dave Sheingold (2011-10-12). "Korean language ballots coming to Bergen County". © 2011 North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ a b Richard Newman (2012-08-30). "Korean company to buy Fort Lee bank". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates - Geographies - Bergen County, New Jersey". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ^ James O'Neill (February 22, 2015). "Mahwah library hosts Korean tea ceremony to celebrate new year". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ^ RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA (2010-12-15). "PALISADES PARK JOURNAL As Koreans Pour In, a Town Is Remade". The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ Korean American Population Data National Association of Korean Americans (Source: 2000 U.S. Census)

- ^ "Destination by Country, 1953-2007", Statistics on Overseas Koreans, South Korea: Overseas Korean Foundation, 2007, retrieved 2009-05-31

- ^ S0201. Selected Population Profile in the United States, United States Census Bureau, retrieved 2007-09-22

- ^ "In North Korea, a brutal choice". CNN. 2012-03-26.

- ^ Kim, Victoria (2012-01-10). "Wary of notice and trying to fit in". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Monsy Alvarado (January 13, 2014). "North Jersey Korean Americans celebrate another year of community's emergence". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Patterson, Wayne (2000), The Ilse: First-Generation Korean Immigrants in Hawai'i, 1903-1972, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 1–11, ISBN 0-8248-2241-2

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013 Lawful Permanent Residents Supplemental Table 1". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ Laux, H. C.; Theme, G. (2006). "Koreans in Greater Los Angeles: socioeconomic polarization, ethnic attachment, and residential patterns". In Li, W. (ed.). From urban enclave to ethnic suburb: New Asian communities in Pacific Rim countries. Honolulu: U of Hawaii Press. pp. 95–118. ISBN 0-8248-2911-5.

- ^ Youngmin Lee; Kyonghwan Park (2008). Negotiating hybridity: transnational reconstruction of migrant subjectivity in Koreatown, Los Angeles. Vol. 25. pp. 245–262. doi:10.1080/08873630802433822.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Abelmann, Nancy; Lie, John (1997). Blue dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles riots. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07705-9.

- ^ David Zahniser (2012-08-01). "Koreatown residents sue L.A. over redistricting". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ "Koreatown Crime". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ "Oakland's got Seoul / Koreatown emerges as hub of Asian culture and downtown's rebirth". SF Gate. Oakland. June 13, 2002.

- ^ Park, Edward J. W. (1998). "Competing visions: Political formation of Korean Americans in Los Angeles, 1992-1997". Amerasia Journal. 24 (1): 41–57.

- ^ Abelmann, Nancy; Lie, John (1997). Blue dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles riots. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 184–185. ISBN 0-674-07705-9.

- ^ "Bergen County Academies Parent Partnership Organization - Korean PPO". Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ "The Korean-American Association of New Jersey". Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ Aaron Morrison (September 27, 2014). "Korean Medical Program draws 1,500 to Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ Karen Rouse (September 29, 2013). "North Jersey Korean health fair data help track risks". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ Barbara Williams (2012-10-20). "Annual Korean health fair draws crowds at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-10-21.

- ^ Barbara Williams (2012-11-24). "Holy Name will screen 2,000 for Hepatitis B". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ^ Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues Second Edition, Edited by Pyong Gap Min. Pine Forge Press - An Imprint of Sage Publications, Inc. 2006. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ BrianYarvin (2008-06-13). "Jersey Dispatch: Bergen County Koreatown". Newyork.seriouseats.com. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ Sachi Fujimori, Elyse Toribio (2012-09-22). "'Gangnam Style' dance craze catches fire in North Jersey". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ^ Mary Diduch (September 14, 2013). "Koreans in North Jersey give thanks at harvest festival". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ a b S.P. Sullivan (June 8, 2013). "Sexual slavery issue, discussed internationally, pivots around one little monument in N.J." New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ John C. Ensslin (2011-12-20). "North Jersey Korean-Americans relieved but worried about transition". © 2011 North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ^ "Korean War vets honored at Cresskill church". © 2011 North Jersey Media Group. 2011-06-26. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ "Hackensack attorney appointed to court". © 2011 North Jersey Media Group. 2011-01-15. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ "Hackensack attorney appointed to court". © 2011 North Jersey Media Group. 2011-01-15. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ^ Monsy Alvarado (January 24, 2012). "North Jersey Koreans welcome state Supreme Court nomination". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ^ Kate Zernike (January 23, 2012). "Christie Names a Gay Man and an Asian for the Top Court". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- ^ Juliet Fletcher (January 23, 2012). "Christie nominates gay black man, Asian to N.J. Supreme Court - video". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- ^ Baxter, Christopher (March 25, 2012). "In rejecting Supreme Court nominee Phillip Kwon, Dems send Gov. Christie a message". Star Ledger. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ SHAWN BOBURG AND JOHN REITMEYER (2012-07-26). "Update: Philip Kwon, rejected N.J. Supreme Court nominee, scores a top Port Authority job". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved 2012-07-29.

- ^ Monsy Alvarado (2012-09-04). "Bergen County swears in first female Korean-American assistant prosecutor". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- ^ Karen Sudol and Dave Sheingold (2011-10-12). "Korean language ballots coming to Bergen County". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- ^ "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates - Geographies - Bergen County, New Jersey". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ John C. Ensslin (2012-08-20). "After decades of work, Bergen County Koreans have earned political respect". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ^ a b Rebecca D. O'Brien (2012-10-14). "New Jersey's Korean community awakens politically". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2012-10-19.

- ^ Monsy Alvarado (2012-10-09). "Korean-Americans to sponsor three debates". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Monsy Alvarado (May 12, 2014). "South Korean officials, Menendez lead Englewood discussion on improving joint economy". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Kirk Semple (May 18, 2012). "In New Jersey, Memorial for 'Comfort Women' Deepens Old Animosity". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Monsy Alvarado (July 12, 2012). "Palisades Park monument to 'comfort women' stirs support, anger". © 2012 North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- ^ Dan Ivers (April 6, 2013). "Critics cause Fort Lee to reconsider monument honoring Korean WWII prostitutes". New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ Linh Tat (April 4, 2013). "Controversy puts planned 'comfort women' memorial in Fort Lee on hold". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ S.P. Sullivan (March 8, 2013). "Bergen County marks International Women's Day with Korean 'comfort women' memorial". © 2013 New Jersey On-Line LLC. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ^ Monsy Alvarado (March 8, 2013). "Memorial dedicated to women forced into sexual slavery during WWII". 2013 North Jersey Media Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ^ Matthew McGrath (December 28, 2015). "Mixed reaction to Japan apology on 'comfort women'". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Linh Tat (May 16, 2013). "Korean group petitions schools over textbook". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ Matt Friedman (February 14, 2014). "New Jersey lawmakers cause international stir with bill to rename 'Sea of Japan'". New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ John C. Ensslin and Michael Linhorst (February 14, 2014). "What's in a name: Bergen state lawmakers push Korean claim that Sea of Japan is East Sea". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ David Sherfinski (April 3, 2014). "Virginia's 'East Sea' textbook bill a nod to Korean Americans". The Washington Times. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ^ Monsy Alvarado (May 2, 2014). "Palisades Park library creates memorial for South Korean ferry victims". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ Sarah Maslin Nir, contributors Sarah Cohen, Jiha Ham, Jeanne Li, Yuhan Liu, Julie Turkewitz, Isvett Verde, Yeong-Ung Yang and Heyang Zhang, and research by Susan C. Beachy (May 7, 2015). "The Price of Nice Nails - Manicurists are routinely underpaid and exploited, and endure ethnic bias and other abuse, The New York Times has found". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Konglish". Koreatimes.co.kr. 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ Lobe, Jim (2004-09-16), "Asian-Americans lean toward Kerry", Asia Times, retrieved 2008-05-16

- ^ a b Lee, Bryan (2009), "The Asian American Vote in the 2008 Presidential Election" (PDF), AALDEF

- ^ naasurvey.com

- ^ "Korean Americans hate gay marriage the most", SF Weekly, 2010-07-20, retrieved 2010-12-10

- ^ a b "2012 AALDEF exit poll" (PDF). AALDEF.

- ^ Woo, Jaeyeon (May 13, 2013). "Sexual Assault Allegations Prompt Presidential Apology". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ^ Woo, Jaeyeon (May 12, 2013). "South Korea apology for Yoon Chang-jung US sex scandal". BBC. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ^ http://www.kpca.org www.kpca.org

- ^ www.naparc.org/member-churches/

- ^ http://l2foundation.org/2009/how-many-asian-american-churches-in-the-usa

- ^ Suh, Sharon A. (2004), Being Buddhist in a Christian World: Gender and Community in a Korean American Temple, University of Washington Press, pp. 3–5, ISBN 0-295-98378-7

- ^ a b Lee, Jonathan H. X.; Kathleen M. Nadeau (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American folklore and folklife. ABC-CLIO. p. 703. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5.

- ^ Yoo, David; Ruth H. Chung (2008). Religion and spirituality in Korean America. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07474-5.

- ^ Park, Chang-Won (10 June 2010). Cultural Blending in Korean Death Rites. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-4411-1749-6.

- ^ Oum, Young-Rae (2005), "Authenticity and representation: cuisines and identities in Korean-American diaspora", Postcolonial Studies, 8 (1): 109, doi:10.1080/13688790500134380

- ^ Edge, John T. (2010-07-28), "The Tortilla Takes a Road Trip to Korea", The New York Times, retrieved 2010-07-28

- ^ "Palisades Park, NJ: K-Town West of Hudson". WordPress.com. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Karen Tina Harrison (2007-12-19). "Thriving Korean communities make Fort Lee and Palisades Park a boon to epicures". Copyright © 2012 New Jersey Monthly Magazine. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Melanie Lefkowitz (2011-04-30). "Bergen County's Fort Lee: Town With a View". The Wall Street Journal - Copyright ©2012 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Elisa Ung (February 9, 2014). "Ung: Destination spot for desserts". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ Elisa Ung (June 12, 2014). "Five Korean dishes to try this summer". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ Pete Wells (December 16, 2014). "In Queens, Kimchi Is Just the Start - Pete Wells Explores Korean Restaurants in Queens". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ Joan Verdon (June 5, 2014). "Korean coffee chain expanding in North Jersey". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Michael Hoefer; Nancy Rytina; Bryan C. Baker (January 2010). "Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2009" (PDF). DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

Further reading

- Abelmann, Nancy and Lie, John. Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles Riots. (1995). 272 pp.

- Kibria, Nazli. Becoming Asian American: Second-Generation Chinese and Korean American Identities (2003)

- Korean American Historical Society, comp. Han in the Upper Left: A Brief History of Korean Americans in the Pacific Northwest. (Seattle: Chin Music, 2015. 103 pp.)

- Min, Pyong Gap. Caught in the Middle: Korean Communities in New York and Los Angeles. (1996). 260 pp.

- Oh, Arissa H., “From War Waif to Ideal Immigrant: The Cold War Transformation of the Korean Orphan,” Journal of American Ethnic History (2012), 31#1 pp 34–55.

- Park, Kyeyoung. The Korean American Dream: Immigrants and Small Business in New York City (1997)

- Park, Kyu Young. Korean Americans in Chicago (2003)

External links

- KoreanAmericanStory.org: A Non-profit Organization Dedicated to Preserving Stories of Korean-Americans

- Arirang - Interactive History of Korean Americans

- AsianWeek: Korean American Timeline

- KoreAm Journal

- Korean-American Community and Directory

- Korean American Foundation

- Korean American Heritage Foundation

- Korean American Historical Society

- Korean American History

- Korean American literature

- Korean-American Ministry Resources (Listing of Korean-American churches)

- The Korean American Museum

- Early Korean Immigrants to America: Their Role in the Establishment of the Republic of Korea