Lichen planus

| Lichen planus | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Dermatology |

Lichen planus (LP) is an uncommon disease of the skin with a prevalence reported between 0.1–0.3% in men and women respectively. The cause is unknown, but it is thought to be the result of an autoimmune process with an unknown initial trigger. There is no cure, but many different medications and procedures have been used in efforts to control the symptoms.

The term lichenoid reaction (or lichenoid lesion) refers to a lesion of similar or identical histopathologic and clinical appearance to lichen planus (i.e. an area which looks the same as lichen planus, both to the naked eye and under a microscope).[1][2] Sometimes dental materials or certain medications can cause a lichenoid reaction.[1] They can also occur in association with graft versus host disease.[1][3]: 258

Classification

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the skin, mucous membranes and nails.[4]

Lichen planus lesions are so called because of their "lichen-like" appearance[5] and can be classified by the site they involve, or by their morphology.

Site

Lichen planus may be categorized as affecting mucosal or cutaneous surfaces.

- Cutaneous forms are those affecting the skin, scalp, and nails.[6][7][8]

- Mucosal forms are those affecting the lining of the gastrointestinal tract (mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, anus), larynx, and other mucosal surfaces including the genitals, peritoneum, ears, nose, bladder and conjunctiva of the eyes.[9][10][11]

Pattern

Lichen planus lesions can occur in many different forms:

| Lesion morphology | Description[12][13] |

|---|---|

| Annular | 'Ring-shaped' lesions that develop gradually from single small pigmented spots into circular groups of papules with clear, unaffected skin in the center. Annular lesions occur in approximately ten percent of lichen planus cases. The ring-like lesions may very slowly enlarge, co-join and morph into larger irregular (serpentine) bands, sometimes accompanied by lines (See Linear, below). |

| Linear | Papules are arranged in a line (the "Blaschko line").[14] This pattern may develop secondary to trauma (koebnerization) or, uncommonly, as a spontaneous, isolated eruption, usually on the extremities, and rarely on the face.[15] |

| Hypertrophic | This pattern usually occurs on the extremities, especially the shins and the interphalangeal joints, and tends to be the most pruritic variant of lichen planus. Also known as "Lichen planus verrucosus". |

| Atrophic | This morphology is characterized by the presence of a few well-demarcated, white-bluish papules or plaques with central superficial atrophy. This is a rare variant of lichen planus. |

| Bullous | This morphology is characterized by the development of vesicles and bullae with the skin lesions. This is a rare variant of lichen planus, and also known as "Vesiculobullous lichen planus". |

| Ulcerative | This morphology is characterized by chronic, painful bullae and ulceration of the feet, often with cicatricial sequelae evident. This is a rare variant of lichen planus. |

| Pigmented | This morphology is characterized by hyperpigmented, dark-brown macules in sun-exposed areas and flexural folds. This is a rare variant of lichen planus. |

Overlap syndromes

Occasionally, lichen planus is known to occur with other conditions. For example:

- Lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome. Lesions of this syndrome share features of both lupus erythematosus and lichen planus. Lesions are usually large and hypopigmented, atrophic, and with a red-to-blue colour and minimal scaling. Telangectasia may be present.[13][16]

- Lichen sclerosus overlap syndrome, sharing features of lichen planus and lichen sclerosus.[17]

Signs and symptoms

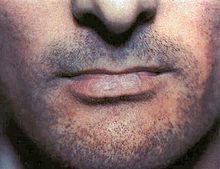

Although lichen planus can present with a variety of lesions, the most common presentation is as a well-defined area of purple-coloured, itchy, flat-topped papules with interspersed lacy white lines (Wickham's striae). This description is known as the characteristic "6 Ps" of lichen planus: planar (flat-topped), purple, polygonal, pruritic, papules, and plaques.[8] This rash, after regressing, is likely to leave an area of hyperpigmentation that slowly fades. That said, a variety of other lesions can also occur.[5]

Cutaneous lichen planus

Variants of cutaneous lichen planus are distinguished based upon the appearance of the lesions and/or their distribution.[18] Lesions can affect the:

- Extremities (face, dorsal hands, arms, and nape of neck).[a] This is more common in Middle Eastern countries in spring and summer, where sunlight appears to have a precipitating effect.[15][19][20]

- Palms and soles

- Intertriginous areas of the skin. This is also known as "Inverse lichen planus".[15]

- Nails[21] characterized by irregular longitudinal grooving and ridging of the nail plate, thinning of the nail plate, pterygium formation, shedding of the nail plate with atrophy of the nail bed, subungual keratosis, longitudinal erthronychia (red streaks), and subungual hyperpigmentation.[22] A sand-papered appearance is present in around 10% of individuals with nail lichen planus.[21]

- Hair and Scalp. The scalp is rarely effected by a condition known as lichen planopilaris, acuminatus, follicular lichen planus, and peripilaris, characterised by violaceous, adherent follicular scale with progressive scarring alopecia. While lichen planus and lichen planopilaris may occur together, aside from sharing the term ‘lichen’ and revealing inflammation on skin biopsy, there is neither established data on their co-occurrence nor data to suggest a common etiology. Lichen planopilaris is considered an orphan disease with no definitive prevalence data and no proven effective treatments.[23][24]

Other variants may include:

- Lichen planus pemphigoides characterized by the development of tense blisters atop lesions of lichen planus or the development vesicles de novo on uninvolved skin.[25]

- Keratosis lichenoides chronica (also known as "Nekam's disease") is a rare dermatosis characterized by violaceous papular and nodular lesions, often arranged in a linear or reticulate pattern on the dorsal hands and feet, extremities, and buttock, and some cases manifests by sorrheic dermatitis like eruption on the scalp and face, also palmo plantar keratosis has been reported.[15][26][27]

- Lichenoid keratoses (also known as "Benign lichenoid keratosis," and "Solitary lichen planus"[15]) is a cutaneous condition characterized by brown to red scaling maculopapules, found on sun-exposed skin of extremities.[15][28] Restated, this is a cutaneous condition usually characterized by a solitary dusky-red to violaceous papular skin lesion.[29]

- Lichenoid dermatitis represents a wide range of cutaneous disorders characterized by lichen planus-like skin lesions.[15][28]

Mucosal lichen planus

Lichen planus affecting mucosal surfaces may have one lesion or be multifocal.[30] Examples of lichen planus affecting mucosal surfaces include:[30]

- Esophageal lichen planus, affecting the esophageal mucosa. This can present with difficulty or pain when swallowing due to oesophageal inflammation, or as the development of an esophageal stricture. It has also been hypothesized that it is a precursor to squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus.[10][31]

- Genital lichen planus, which may cause lesions on the glans penis or skin of the scrotum in males, and the vulva or vagina in females.[8] Symptoms may include lower urinary tract symptoms associated with stenosis of the urethra, painful sexual intercourse, and itching.[8] In females, Vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome, is severe and distinct variant affecting the vulva, vagina, and gums, with complications including scarring, vaginal stricture formation,[32] or vulva destruction.[33] The corresponding syndrome in males, affecting the glans penis and gums, is the peno-gingival syndrome.[15] It is associated with HLA-DQB1.[15][34]

Oral lichen planus

Oral lichen planus (also termed oral mucosal lichen planus),[35] is a form of mucosal lichen planus, where lichen planus involves the oral mucosa, the lining of the mouth. This may occur in combination with other variants of lichen planus.[36] Six clinical forms of oral lichen planus are recognized:[36]

- Reticular, the most common presentation of oral lichen planus,[37] is characterised by the net-like or spider web-like appearance of lacy white lines, oral variants of Wickham's straiae.[36] This is usually asymptomatic.[37]

- Erosive/ulcerative, the second most common form of oral lichen planus,[37] is characterised by oral ulcers presenting with persistent, irregular areas of redness, ulcerations and erosions covered with a yellow slough. This can occur in one or more areas of the mouth. In 25% of people with erosive oral lichen planus, the gums are involved, described as desquamative gingivitis (a condition not unique to lichen planus). This may be the initial or only sign of the condition.[36]

- Papular, with white papules.

- Plaque-like appearing as a white patch which may resemble leukoplakia.[36]

- Atrophic, appearing as areas. Atrophic oral lichen planus may also manifest as desquamative gingivitis.[36]

- Bullous, appearing as fluid-filled vesicles which project from the surface.

These types often coexist in the same individual. Oral lichen planus tends to present bilaterally as mostly white lesions on the inner cheek,[37] although any mucosal site in the mouth may be involved. Other sites, in decreasing order of frequency, may include the tongue, lips, gingivae, floor of the mouth, and very rarely, the palate.[37]

Generally, oral lichen planus tends not to cause any discomfort or pain, although some people may experience soreness when eating or drinking acidic or spicy foodstuffs or beverages.[36] When symptoms arise, they are most commonly associated with the atrophic and ulcerative subtypes. These symptoms can include a burning sensation to severe pain.[37] Lichen planus, particularly when concomitant oral or genital lesions occur, significantly affects patients’ quality of life.

Causes

The cause of lichen planus is unknown,[5][34][38] but it is not contagious and does not involve any known pathogen.[39] It is thought to be a T cell mediated autoimmune reaction (where the body's immune system targets its own tissues).[37] This autoimmune process triggers apoptosis of the epithelial cells.[37] Several cytokines are involved in lichen planus, including tumor necrosis factor alpha, interferon gamma, interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin 6, and interleukin 8.[37] This autoimmune, T cell mediated, process is thought to be in response to some antigenic change in the oral mucosa, but a specific antigen has not been identified.[37]

Where a causal or triggering agent is identified, this is termed a lichenoid reaction rather than lichen planus. These may include:[11]

- Drug reactions, with the most common inducers including gold salts, beta blockers, traditional antimalarials (e.g. quinine), thiazide diuretics, furosemide, spironolactone, metformin and penicillamine.[39]

- Reactions to amalgam (metal alloys) fillings (or when they are removed/replaced),[40]

- Graft-versus-host disease lesions, which chronic lichenoid lesions seen on the palms, soles, face and upper trunk after several months.[39]

- Hepatitis, specifically hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection, and primary biliary cirrhosis.[17][39]

It has been suggested that lichen planus may respond to stress, where lesions may present during times of stress. Lichen planus can be part of Grinspan's syndrome.[citation needed]

It has also been suggested that mercury exposure may contribute to lichen planus.[41]

Diagnosis

Lichen planus lesions are diagnosed clinically by their "lichen-like" appearance.[5] A biopsy can be used to rule out conditions that may resemble lichen planus, and can pick up any secondary malignancies.[42]

Histopathology

Lichen planus has a unique microscopic appearance that is similar between cutaneous, mucosal and oral. A Periodic acid-Schiff stain of the biopsy may be used to visualise the specimen. Histological features seen include:[43]

- thickening of the stratum corneum both with nuclei present (parakeratosis) and without (orthokeratosis). Parakeratosis is more common in oral variants of lichen planus.

- thickening of the stratum granulosum

- thickening of the stratum spinosum (acanthosis) with formation of colloid bodies (also known as Civatte bodies, Sabouraud bodies) that may stretch down to the lamina propria.

- liquefactive degeneration of the stratum basale, with separation from the underlying lamina propria, as a result of desmosome loss, creating small spaces (Max Joseph spaces).

- Infiltration of T cells in a band-like pattern into the dermis[37] "hugging" the basal layer.

- Development of a "saw-tooth" appearance of the rete pegs, which is much more common in non-oral forms of lichen planus.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for OLP includes:

- Other oral vesiculo-ulcerative conditions such as Pemphigus vulgaris and Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid

- Lupus erythematosus, with lesions more commonly occur on the palate and appear as centrally ulcerated or erythematous with radiating white striae. In contrast, OLP and lichenoid reactions rarely occur on the palate, and the striae are randomly arranged rather than radial.[44]

- Chronic ulcerative stomatitis

- Frictional keratosis and Morsicatio buccarum (chronic cheek biting)

- Oral leukoplakia

- Oral candidiasis

Treatment

There is no cure for lichen planus,[37] and so treatment of cutaneous and oral lichen planus is for symptomatic relief or due to cosmetic concerns.[5][37][42] When medical treatment is pursued, first-line treatment typically involves corticosteroids,[5] and removal of any triggers.[40] Without treatment, most lesions will spontaneously resolve within 6–9 months for cutaneous lesions,[5] and longer for mucosal lesions.[43] Recently, it was hypothesized that the interferon gamma/CXCL10 axis could be a target to reverse inflammation.[4]

Cutaneous lichen planus

Many different treatments have been reported for cutaneous lichen planus, however there is a general lack of evidence of efficacy for any treatment.[14][45] Treatments tend to be prolonged, partially effective and disappointing.[14] The mainstay of localized skin lesions is topical steroids. Additional treatments include retinoids such as Acitretin, or sulfosalazin. Narrow band UVB phototherapy or systemic PUVA therapy are known treatment modalities for generalized disease.

However, there is striking paucity of evidence regarding therapy, since randomized clinical trials on the medical or physical treatment of LP are lacking.[46]

Oral lichen planus

Reassurance that the condition is benign, elimination of precipitating factors and improving oral hygiene are considered initial management for symptomatic OLP, and these measures are reported to be useful.[37] Treatment usually involves topical corticosteroids (such as betamethasone, clobetasol, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone) and analgesics, or if these are ineffective and the condition is severe, the systemic corticosteroids may be used. Calcineurin inhibitors (such as pimecrolimus, tacrolimus or cyclosporin) are sometimes used.[37]

Prognosis

In contrast to cutaneous lichen planus, lichen planus lesions in the mouth may persist for many years,[42] and tend to be difficult to treat, with relapses being common.[34] Atrophic/erosive lichen planus is associated with a small risk of malignant transformation,[42] and so people with OLP tend to be kept on long term review to detect any potential change early. Sometimes OLP can become secondarily infected with Candida organisms.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of lichen planus in the general population is about 0.1–4.0%.[8] It generally occurs more commonly in females, in a ratio of 3:2, and most cases are diagnosed between the ages of 30 and 60, but it can occur at any age.[8][47]

Oral lichen planus is relatively common,[34] It is one of the most common mucosal diseases. The prevalence in the general population is about 1.27–2.0%,[37][42] and it occurs more commonly in middle aged people.[37] OLP in children is rare. About 50% of females with oral lichen planus were reported to have undiagnosed vulvar lichen planus.[8]

History

Lichen planus was first reported in 1869 by Erasmus Wilson.[43]

Notes

- ^ Cutaneous lichen planus affecting the extremities is also known as "Lichen planus actinicus", "Actinic lichen niditus," "Lichen planus atrophicus annularis," "Lichen planus subtropicus," "Lichen planus tropicus," "Lichenoid melanodermatitis," and "Summertime actinic lichenoid eruption"

References

- ^ a b c Greenberg MS, Glick M, Ship JA (2008). Burket's oral medicine (11th ed.). Hamilton, Ont.: BC Decker. pp. 89–97. ISBN 9781550093452.

- ^ Lewis MA, Jordan RC (2012). Oral medicine (2nd ed.). London: Manson Publishing. pp. 66–72. ISBN 9781840761818.

- ^ Barnes L (editor) (2009). Surgical pathology of the head and neck (3rd ed.). New York: Informa healthcare. ISBN 9781420091632.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Di Lernia, Vito (2016-07-01). "Targeting the IFN-γ/CXCL10 pathway in lichen planus". Medical Hypotheses. 92: 60–61. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2016.04.042.

- ^ a b c d e f g Limited, Therapeutic Guidelines (2009). Therapeutic guidelines (Version 3. ed.). North Melbourne, Vic.: Therapeutic Guidelines. pp. 254–255, 302. ISBN 978-0-9804764-3-9.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Asch, S; Goldenberg, G (March 2011). "Systemic treatment of cutaneous lichen planus: an update". Cutis; cutaneous medicine for the practitioner. 87 (3): 129–34. PMID 21488570.

- ^ Sharma, A; Białynicki-Birula, R; Schwartz, RA; Janniger, CK (July 2012). "Lichen planus: an update and review". Cutis; cutaneous medicine for the practitioner. 90 (1): 17–23. PMID 22908728.

- ^ a b c d e f g Le Cleach, Laurence; Chosidow, Olivier (23 February 2012). "Lichen Planus". New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (8): 723–732. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103641.

- ^ Cheng, S; Kirtschig, G; Cooper, S; Thornhill, M; Leonardi-Bee, J; Murphy, R (Feb 15, 2012). "Interventions for erosive lichen planus affecting mucosal sites". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2: CD008092. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008092.pub2. PMID 22336835.

- ^ a b Yamada T, Alpers DH, et al. (2009). Textbook of gastroenterology (5th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. p. 3304. ISBN 978-1-4051-6911-0.

- ^ a b Treister NS, Bruch JM (2010). Clinical oral medicine and pathology. New York: Humana Press. pp. 59–62. ISBN 978-1-60327-519-4.

- ^ Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 465–8. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ a b James, William D.; Elston, Dirk M.; Berger, Timothy G. Andrews' Diseases of the skin : clinical dermatology (11th ed.). London: Saunders/ Elsevier. pp. 219–24. ISBN 1-4377-0314-3.

- ^ a b c Gorouhi, F; Firooz A; Khatami A; Ladoyanni E; Bouzari N; Kamangar F; Gill JK (2009). "Interventions for cutaneous lichen planus". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008038.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L.; Rapini, Ronald P., eds. (2008). Dermatology (2nd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier. ISBN 1-4160-2999-0.

- ^ Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 366, 470–1. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ a b James, William D.; Elston, Dirk M.; Berger, Timothy G. Andrews' Diseases of the skin : clinical dermatology (11th ed.). London: Saunders/ Elsevier. p. 220. ISBN 1-4377-0314-3.

- ^ Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 466. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 468. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk M.; Berger, Timothy G. Andrews' Diseases of the skin : clinical dermatology (11th ed.). London: Saunders/ Elsevier. p. 223. ISBN 1-4377-0314-3.

- ^ a b Gordon, KA; Vega, JM; Tosti, A (Nov–Dec 2011). "Trachyonychia: a comprehensive review". Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 77 (6): 640–5. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.86470. PMID 22016269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk M.; Berger, Timothy G. Andrews' Diseases of the skin : clinical dermatology (11th ed.). London: Saunders/ Elsevier. p. 781. ISBN 1-4377-0314-3.

- ^ "Orphanet: Rare Diseases". Orphanet. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ "Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation". www.carfintl.org. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 471. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 472. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk M.; Berger, Timothy G. Andrews' Diseases of the skin : clinical dermatology (11th ed.). London: Saunders/ Elsevier. p. 224. ISBN 1-4377-0314-3.

- ^ a b Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 473. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk M.; Berger, Timothy G. Andrews' Diseases of the skin : clinical dermatology (11th ed.). London: Saunders/ Elsevier. p. 639. ISBN 1-4377-0314-3.

- ^ a b Ebrahimi, M; Lundqvist, L; Wahlin, YB; Nylander, E (October 2012). "Mucosal lichen planus, a systemic disease requiring multidisciplinary care: a cross-sectional clinical review from a multidisciplinary perspective". Journal of lower genital tract disease. 16 (4): 377–80. doi:10.1097/LGT.0b013e318247a907. PMID 22622344.

- ^ Chandan, VS; Murray, JA; Abraham, SC (June 2008). "Esophageal lichen planus". Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 132 (6): 1026–9. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2008)132[1026:ELP]2.0.CO;2. PMID 18517264.

- ^ Panagiotopoulou, N; Wong, CS; Winter-Roach, B (April 2010). "Vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome". Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 30 (3): 226–30. doi:10.3109/01443610903477572. PMID 20373919.

- ^ Schlosser, BJ (May–Jun 2010). "Lichen planus and lichenoid reactions of the oral mucosa". Dermatologic therapy. 23 (3): 251–67. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01322.x. PMID 20597944.

- ^ a b c d Nico, MM; Fernandes, JD; Lourenço, SV (Jul–Aug 2011). "Oral lichen planus". Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 86 (4): 633–41, quiz 642–3. PMID 21987126.

- ^ Alam, F; Hamburger, J (May 2001). "Oral mucosal lichen planus in children". International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 11 (3): 209–14. PMID 11484471.

- ^ a b c d e f g Scully C (2008). Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 192–199. ISBN 9780702049484.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Thongprasom, K; Carrozzo, M; Furness, S; Lodi, G (Jul 6, 2011). "Interventions for treating oral lichen planus". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (7): CD001168. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001168.pub2. PMID 21735381.

- ^ Roopashree, MR; Gondhalekar, RV; Shashikanth, MC; George, J; Thippeswamy, SH; Shukla, A (November 2010). "Pathogenesis of oral lichen planus--a review". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 39 (10): 729–34. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00946.x. PMID 20923445.

- ^ a b c d Colledge, Nicki R.; Brian R. Walker; Stuart H. Ralston (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. illustrated by Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1265–1266. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ^ a b Issa, Y; Brunton, PA; Glenny, AM; Duxbury, AJ (November 2004). "Healing of oral lichenoid lesions after replacing amalgam restorations: a systematic review". Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 98 (5): 553–65. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.12.027. PMID 15529127.

- ^ Dunsche A, Frank MP, Lüttges J, et al. (April 2003). "Lichenoid reactions of murine mucosa associated with amalgam". The British Journal of Dermatology. 148 (4): 741–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05229.x. PMID 12752133.

- ^ a b c d e Kerawala C, Newlands C, eds. (2010). Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 412–413. ISBN 978-0-19-920483-0.

- ^ a b c Scully, C.; El-Kom, M. (1 July 1985). "Lichen planus: review and update on pathogenesis". Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. 14 (6): 431–458. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00516.x.

- ^ Odell EW (Editor) (2010). Clinical problem solving in dentistry (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 159–162, 192. ISBN 9780443067846.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Cribier, B; Frances, C; Chosidow, O (December 1998). "Treatment of lichen planus. An evidence-based medicine analysis of efficacy". Archives of dermatology. 134 (12): 1521–30. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.12.1521. PMID 9875189.

- ^ Antiga, E.; Caproni, M.; Parodi, A.; Cianchini, G.; Fabbri, P. (2014-12-01). "Treatment of cutaneous lichen planus: an evidence based analysis of efficacy by the Italian Group for Cutaneous Immunopathology". Giornale Italiano Di Dermatologia E Venereologia: Organo Ufficiale, Società Italiana Di Dermatologia E Sifilografia. 149 (6): 719–726. ISSN 0392-0488. PMID 25664824.

- ^ Yu TC, Kelly SC, Weinberg JM, Scheinfeld NS (March 2003). "Isolated lichen planus of the lower lip". Cutis. 71 (3): 210–2. PMID 12661749.