Megalopolis (film)

| Megalopolis | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

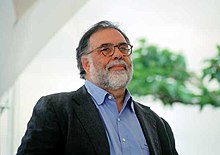

| Directed by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Written by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Mihai Mălaimare Jr. |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Osvaldo Golijov |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Lionsgate Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $120 million |

Megalopolis[a] is a 2024 American epic science fiction drama film written, directed, and produced by Francis Ford Coppola. It features an ensemble cast including Adam Driver, Giancarlo Esposito, Nathalie Emmanuel, Aubrey Plaza, Shia LaBeouf, Jon Voight, Laurence Fishburne, Talia Shire, Jason Schwartzman, Kathryn Hunter, Grace VanderWaal, Chloe Fineman, James Remar, D. B. Sweeney, and Dustin Hoffman. Set in an imagined modern United States, it follows Cesar Catilina (Driver), a visionary architect, as he clashes with the corrupt Mayor Franklyn Cicero (Esposito) in determining how to rebuild the metropolis of New Rome after a devastating disaster. The film references the characters involved in the Catilinarian conspiracy of 63 BC, including Catiline and Cicero, in addition to Caesar.

Megalopolis was a passion project for Coppola, who wanted to make a film drawing parallels between the fall of Rome and the future of the United States by setting the events of the Catilinarian conspiracy in modern New York. He conceived the idea for the film in 1977, being inspired by the historian Sallust, and actively started developing it by assembling notes for a future script in 1983. Preparations for a film based around his initial concept came together in 1989 to be shot in Rome, but was postponed after Coppola prioritized other projects to pay his debt to Hollywood after a string of box-office disappointments. Coppola revived the project in 2001, holding table reads with prominent actors in New York. After 9/11, an event that resembled its plot and themes, the film was again abandoned. Having become disheartened working for the studio system, Coppola soon after declared his intentions to self-finance the project if it ever came to fruition.

Coppola announced his return to the film in 2019 and, two years after, sold a portion of his winery in California to spend $120 million of his own money to fund it. After a delay caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, casting was underway by 2021. The film reunited Coppola with past collaborators, including actors Esposito, Fishburne, Remar, Shire, and Sweeney, cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr., second-unit director Roman Coppola, and composer Osvaldo Golijov. Principal photography took place from November 2022 to March 2023, in Georgia. Coppola adopted an experimental style that permitted improvisation during the shoot by letting actors write scenes and himself make spontaneous changes to the script. These methods proved divisive, leading to the resignation of the art department and visual effects team, among others, and raising comparisons to Coppola's history of challenging productions. Filming allegedly wrapped ahead of schedule.

Megalopolis was selected to compete for the Palme d'Or at the 77th Cannes Film Festival, where it premiered on May 16, 2024, and polarized critics. The film is scheduled to be theatrically released in the United States by Lionsgate Films on September 27.

Premise

[edit]An accident destroys a decaying metropolis called New Rome. Cesar Catilina, an idealist architect with the power to control time, aims to rebuild it as a sustainable utopia, while corrupt Mayor Franklyn Cicero remains committed to a regressive status quo. Torn between them is Franklyn's socialite daughter and Cesar's love interest, Julia, who, tired of the influence she inherited, searches for her life's meaning.[2][3]: 6

Cast

[edit]- Adam Driver as Cesar Catilina, a futuristic architect and the Chairman of the Design Authority in New Rome, blessed with the ability to stop time[4]

- Giancarlo Esposito as Mayor Franklyn Cicero, the arch-conservative mayor of New Rome[4]

- Nathalie Emmanuel as Julia Cicero, Cesar's love interest and Franklyn's daughter[4]

- Aubrey Plaza as Wow Platinum, a TV presenter specializing in financial news who loves Cesar[3]: 12 [4]

- Shia LaBeouf as Clodio Pulcher, Cesar's cousin who lusts for Julia[3]: 13 [4]

- Jon Voight as Hamilton Crassus III, Cesar's wealthy uncle and the head of Crassus National Bank[4][5]

- Laurence Fishburne as Fundi Romaine (the film's narrator), Cesar's driver and assistant[6]

- Talia Shire as Constance Crassus Catilina, Cesar's mother[7]

- Jason Schwartzman as Jason Zanderz, a member of Franklyn's entourage[7]

- Kathryn Hunter as Teresa Cicero, Franklyn's wife[7]

- Grace VanderWaal as Vesta Sweetwater, a virginal teen pop star[4]

- Chloe Fineman as Clodia Pulcher[3]: 33

- James Remar as Charles Cothope[3]: 33

- D. B. Sweeney as Commissioner Stanley Hart[3]: 33

- Isabelle Kusman as Claudine Pulcher[3]: 33

- Bailey Ives as Huey Wilkes[3]: 34

- Madeleine Gardella as Claudette Pulcher[3]: 34

- Balthazar Getty as Aram Kazanjian, Clodio's right-hand man[7]

- Romy Mars as Girl Reporter[3]: 34

- Haley Sims as Sunny Hope Catilina[3]: 34

- Dustin Hoffman as Nush Berman, Franklyn's fixer[7]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Growing up in New York City, Francis Ford Coppola was fascinated by science fiction films, such as Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927) and William Cameron Menzies's Things to Come (1936), and the scientific community's history with dangerous experiments.[8] His reading of the Roman historian Sallust and William Bolitho Ryall's book Twelve Against the Gods (1929) inspired him to make a film about Lucius Sergius Catiline, who sought consulship by campaigning to eliminate debt for the poor and wealthy, but lost to Marcus Tullius Cicero, who famously denounced Catilina before the Senate for conspiring to overthrow the Roman Republic in 63 BC.[3]: 7 Coppola conceived the overall idea for Megalopolis towards the end of filming Apocalypse Now (1979) in 1977.[9]: 50 Sound designer Richard Beggs described Coppola's vision as an opera screened over four nights, similar to Richard Wagner's Ring cycle (1876) in Bayreuth, in a "gigantic outdoor purpose-built theatre" in "some place as close as possible to the geographical center of the United States", for example the Red Rocks Amphitheatre in the state of Colorado.[10][11]: 181

Coppola devoted the beginning of 1983 to developing the film, assembling four hundred pages of notes and script fragments in two months.[12]: 333 Over the next four decades, he collected clippings and notes for a scrapbook detailing intriguing subjects he envisioned incorporating into a future screenplay, like political cartoons and different historical subjects, before deciding to make a Roman epic film set in an imagined modern America.[3]: 6 [8] In mid-1983, he described the plot as taking place in one day in New York City with Catiline Rome as a backdrop, similar to how James Joyce's modernist novel Ulysses (1922) used Homer in the context of modern Dublin and how he had updated the setting of Joseph Conrad's novella Heart of Darkness (1899) from the late 1800s amid the European colonial rule in Africa to the 1970s Vietnam War for Apocalypse Now.[8][13]: 74 [14]: 215

In January 1989, Coppola announced his intentions to endeavor on Le Ribellion di Catilina, a film "so big and complicated it would seem impossible", which biographer Michael Schumacher said "sounded much like what he had in store for Megalopolis".[12]: 409–410 It was to be shot in Cinecittà, a large film studio in Rome, Italy, where production designer Dean Tavoularis and his design team built offices and an art studio for drafters to storyboard the film.[15]: 266 [16]: 234 The Hollywood Reporter described it as "swing[ing] from the past to the present", merging "the images of Rome ... with the New York of today".[12]: 410 Following the 1990–91 film awards season for The Godfather Part III (1990), Coppola's production company, American Zoetrope, announced several projects in development, including plans to film Megalopolis in 1991, despite lacking a finished script.[12]: 436 However, the film was postponed to "no earlier than 1996" after Coppola found himself prioritizing other projects, including Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), Jack (1996), and The Rainmaker (1997), to get out of debt accumulated from One from the Heart (1982) and Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988).[12]: 444 [17]: 110 [18]

"Do films the same way Ingmar Bergman did them, with a little group of collaborators that you know, making a script that you wrote. Otherwise, you will finally get beaten down by the fact that you are making things that you are not really interested in, from a script that you don't fully understand, by means that you don't approve of. The question is: Can you make bigger films, like Megalopolis or Cure, in that way? Certainly, the determining factor is the cast, because with a star cast comes the financing ..."

— Coppola, diary entry (August 15, 1992)[19]: 28

In 2001, Coppola held table reads in a production office in Park Slope, Brooklyn, with actors including Nicolas Cage (Coppola's nephew), Russell Crowe, Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, Edie Falco, James Gandolfini, Jon Hamm, Paul Newman, Al Pacino, Kevin Spacey, and Uma Thurman.[8][20][21] Other actors considered included Matt Dillon, approached during the filming of Rumble Fish (1983) for the role of a cadet who goes AWOL, and Parker Posey, though Coppola dispelled rumors he had written a part specifically for Warren Beatty.[15]: 262 [22][23] Jim Steranko, who previously created production illustrations for Bram Stoker's Dracula, produced concept art for Megalopolis at Coppola's behest, described in James Romberger's master's thesis as "expansive, elaborate and carefully rendered pencil or charcoal halftone architectural drawings of huge buildings and urban plazas that appeared to mix ancient Roman, art deco and speculative sci-fi stylizations".[9]: 54 Proposed filming locations included the cities of Montreal and New York, with an anticipated budget of $50–80 million (equivalent to $82.2 million to $131 million in 2023).[15]: 263 [23][24]

That year, Coppola and cinematographer Ron Fricke recorded second unit footage of New York, thinking it would be simpler to do so before principal photography, with the 24-frames per second Sony F900 digital camera that George Lucas used for Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (1999).[3]: 8–9, 15 [8][24] After the September 11 attacks, during which Coppola and his team were location scouting in New York, the roughly thirty hours of footage was stashed, including more material they shot two weeks after, due to its resemblance to the script, which involved a Soviet satellite crashing into Earth and destroying a section of downtown New York.[9]: 54 [15]: 263 [25][26] "I feel as though history has come to my doorstep", Coppola said in October, declaring his plans to rewrite the film.[24] In 2002, he shot sixty to seventy hours of second unit footage in Manhattan on high-definition video that Lucas described as "wide shots of cities with incredible detail at magic hour and all kinds of available-light material".[15]: 263 [27][28]: 82 He also disclosed his intent to self-finance the film, still in place as his next project, having become disheartened making films to pay off his debt to Hollywood.[22][29]

Production on the film eventually halted. The success of his winery and resorts meant Coppola could produce it with his own money, which his friend Wendy Doniger said "paralyzed him", adding that, "He had no excuse this time if the film was no good. What froze him was having the power to do exactly what he wanted so that his soul was on the line".[30] In 2005, she gave him books that she deemed thematically relevant, including Mircea Eliade's Youth Without Youth (1976), a novella about a 70-year-old man struggling to complete an ambitious project. Coppola then shelved Megalopolis to self-finance a small-scale adaptation of the book, intended to be "the opposite of Megalopolis".[28]: 85 [30] In 2007, Coppola admitted that 9/11 "made it really pretty tough ... a movie about the aspiration of utopia with New York as a main character and then all of a sudden you couldn't write about New York without just dealing with what happened and the implications of what happened. The world was attacked and I didn't know how to try to do with that [sic]. I tried".[18] In 2009, in regards to the likelihood of revisiting the film, he said, "Someday, I'll read what I had on Megalopolis and maybe I'll think different of it, but it's also a movie that costs a lot of money to make and there's not a patron out there. You see what the studios are making right now."[31]

Pre-production

[edit]Bottom: Aubrey Plaza, Shia LaBeouf, and Jon Voight

On April 3, 2019, the day before his 80th birthday, Coppola announced his return to the project, having completed the script and approached Jude Law and Shia LaBeouf for lead roles.[32][25] In 2021, Coppola sold his Sonoma County wineries in a deal valued between $500 million and $1 billion to reportedly spend $120 million of his own money to produce the film.[8][33][34] By August, discussions with actors to star in the film had begun; James Caan was set to star after petitioning Coppola to write him a cameo role as a potential swan song, while Cate Blanchett, Oscar Isaac, Jessica Lange, Michelle Pfeiffer, Jon Voight, Forest Whitaker, and Zendaya were in various stages of negotiations.[3]: 3 [35]

In late 2021, Nathalie Emmanuel auditioned over Zoom while filming The Invitation (2022) in Budapest. During the session, Coppola had her participate in an acting exercise, tasking her with reciting a line from Alice Walker's novel The Color Purple (1982) in as many different contexts.[3]: 3 [36][37] Plaza similarly auditioned over Zoom sometime in 2022 during the production of the second season of The White Lotus while staying at the San Domenico, the same hotel in Italy that Coppola resided in during the filming of The Godfather (1972). Before the meeting, Coppola had emailed her the entire script and asked her to consider the role of "Wow Platinum", wanting an actress with a similar screen presence to Jean Harlow and Myrna Loy in screwball comedies from the 1930s.[3]: 3 [38]

By March 2022, Talia Shire (Coppola's sister) expressed her interest in joining the cast and Isaac was reported to have passed on the project.[39][40] By May, Emmanuel, Voight, and Whitaker were confirmed for the cast, with Adam Driver and Laurence Fishburne added.[41] After Caan died on July 6, 2022, his role was given to Dustin Hoffman.[3]: 3 [42] Driver originally demurred from accepting the lead role but reconsidered after Coppola incorporated ideas they developed together.[3]: 3

In August 2022, Kathryn Hunter, Aubrey Plaza, James Remar, Jason Schwartzman (Coppola's nephew and Shire's son), and Grace VanderWaal joined the cast, with LaBeouf and Shire confirmed as part of it.[43][44] Chloe Fineman, Madeleine Gardella, Hoffman, Bailey Ives, Isabelle Kusman, and D. B. Sweeney would be added in October.[45] Coppola had reached out to Fineman, a cast member on Saturday Night Live, in 2020 after seeing her perform at a theater comedy event where she impersonated Ivana and Melania Trump.[46][47] In January 2023, Giancarlo Esposito was confirmed to star.[48] VanderWaal, whom Coppola met through her father, wrote original songs for the film.[49] Esposito, Fishburne, Remar, Shire, and Sweeney previously worked with Coppola.[3]: 2

Books that the film was influenced by included Bullshit Jobs (2018), The Dawn of Everything (2021), and Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011) by David Graeber; The Chalice and the Blade (1987) by Riane Eisler; The Glass Bead Game (1943) by Hermann Hesse; The Origins of Political Order (2011) by Francis Fukuyama; The Swerve (2011) by Stephen Greenblatt; and The War Lovers (2010) by Evan Thomas.[50] The character of Cesar was based on Catiline and renamed at classicist Mary Beard's suggestion that Julius Caesar had ties with Catiline and was far more known among audiences. Coppola said the character was inspired by Robert Moses as portrayed in Robert Caro's biography The Power Broker (1974) and architects like Norman Bel Geddes, Walter Gropius, Raymond Loewy, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Coppola also researched the Claus von Bülow murder case, the Mary Cunningham-William Agee Bendix Corporation scandal, the emergence of New York Stock Exchange reporter Maria Bartiromo, the history of Studio 54, and Felix Rohatyn's solution for the New York City fiscal crisis of 1975.[8] The fictional building material of Megalon was based in part on the work of architect and designer Neri Oxman, who appears in the film as "Dr. Lyra Shir".[3]: 10, 35 In line with The Godfather and Bram Stoker's Dracula, where he credited Mario Puzo and Bram Stoker as the original writers, Coppola branded the film with his name as Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis.[8]

The COVID-19 pandemic delayed the start of production. Before filming began, a week of rehearsals took place with theater-style exercises, much like the one Emmanuel described having in her audition.[36] Plaza described Coppola's workshop-style approach as allowing actors to improvise and provide feedback to the script, adding, "We wrote scenes and we conducted ourselves like a theater troupe, me and Jon Voight and Shia [LaBeouf]. We were writing scenes and giving them to the script supervisor. And then she would give them to Francis and sometimes he would like it and put it in. But every day he wanted to play. He ran it like it was a theater camp. There were games all day, and we were in character the whole time."[38]

Filming

[edit]Locations

[edit]

Principal photography began on November 7, 2022, in Fayetteville, Georgia, at Trilith Studios and concluded on March 11, 2023. Filming also took place in Atlanta.[3]: 3 It was to be the first film shot on Trilith Studios' Prysm Stage, an LED virtual production volume, but due to budget constraints, the production pivoted to a "less costly, more traditional greenscreen approach".[51][52][53] The decision to film in Georgia over the film's setting of New York was due to available tax benefits, studio facilities, local crews, and classical buildings to act as sets.[3]: 3 [10] Around July 2023, close to when editing began, additional content was shot on the Italy–Switzerland border.[54]

For the production, Coppola purchased a closed drive-in Days Inn motel for $4.35 million to reside in and accommodate the crew and his extended family. He renovated the motel to include facilities for rehearsal and post-production.[3]: 3 [55] The building in Peachtree City, Georgia, was later opened to the public by Coppola on July 5, 2024, as the All-Movie Hotel.[55] It offers hospitality and facilities needed to make films, including 27 rooms, two edit suites with laser projection and Meyer Sound 2.1 monitoring, two edit bays, offices, an ADR recording room, a conference room, an insert stage, a convivial space, and a screening room for private viewings, editing, or 9.1.6 Dolby Atmos sound mixing with calibrated Meyer sound monitoring, plus a swimming pool, wardrobe fitting room, and gym.[56] Memorabilia from Coppola's previous films is displayed throughout the hotel.[55]

Mihai Mălaimare Jr. served as cinematographer. He previously shot Coppola's Youth Without Youth (2007), Tetro (2009), and Twixt (2011).[57] The crew utilized two Arri Alexa 65s and one Alexa LF for the first unit and an Alexa Mini LF for the second unit. Panavision provided the lenses, which included a combination of wide Sphero 65s, Panaspeeds, and specialty lenses such as the 200mm and 250mm detuned Primo Artiste, rehoused Helios, and Lensbaby for specific scenes.[3]: 16 In reference to ancient Rome, some male actors donned Caesar cuts.[58] For Plaza, the last two weeks of the shoot overlapped with her role on the television series Agatha All Along (2024). The two projects were shot on the same lot, so she was allowed to do both.[38] In August 2023, during the SAG-AFTRA strike, the film received an interim agreement from the union, possibly for reshoots or for publicity purposes to qualify for festival screenings and distribution deals.[59][60]

Alleged conflicts on set

[edit]Creative differences

[edit]Plaza spoke positively about Coppola's willingness to experiment and how sometimes "all of a sudden, he would have another idea. And then all of a sudden, we're shooting in a different location we didn't even plan to shoot. And then the whole day goes by and you're like, 'I had no idea any of that was going to happen'".[38] Others described that approach as "exasperating" and "old-school", as Coppola was hesitant to decide how the film would look and would spend work days completing shots practically instead of relying on digital techniques. One crew member recalled, "He would often show up in the mornings before these big sequences and because no plan had been put in place, and because he wouldn't allow his collaborators to put a plan in place, he would often just sit in his trailer for hours on end, wouldn't talk to anybody, was often smoking marijuana ... And then he'd come out and whip up something that didn't make sense, and that didn't follow anything anybody had spoken about or anything that was on the page, and we'd all just go along with it, trying to make the best out of it." On Driver's first day on set, Coppola allegedly took six hours to achieve an effect by projecting an image on the side of Driver's head.[10]

On December 9, 2022, Coppola fired most of the visual effects team, with the rest of the department, including supervisor Mark Russell, soon following. In January 2023, reports indicated the budget ballooned higher than its initial $120 million, which The Hollywood Reporter compared to Coppola's history of challenging productions, most notoriously Apocalypse Now. Due to an alleged "unstable filming environment", a claim Coppola and Driver contested, several crew members exited the film, including production designer Beth Mickle and art director David Scott, along with the art department.[53][61] Coppola elaborated that he wanted Megalopolis to have a unique visual style similar to a woven mural or tapestry. Working with concept artist Dean Sherriff to translate his vision through keyframe concept art, he permitted minimal input from the art department, whose practices, having recently completed a Marvel production, he deemed conventional, expensive, and hierarchical. Coppola had originally set $100 million for the budget and $20 million as contingency. As the budget was at risk of rising to $148 million (which he said would have "bankrupted me and my family"), he laid off one of five art directors, leading the entire team to resign. Production allegedly wrapped a week ahead of schedule, with the budget close to the planned $120 million. On firing Russell and replacing him with his nephew Jesse James Chisholm, Coppola said they disagreed over his demand for "live special effects", which he completed with his son and second unit director Roman Coppola as they had with Bram Stoker's Dracula.[3]: 8–9, 15

Allegations of misconduct

[edit]

Anonymous crew members described Coppola's on-set conduct as unprofessional. On February 14, 2023, a "celebratory Studio 54-esque club scene" was filmed at the Tabernacle, a concert hall in Atlanta, for which 150–200 extras were assembled, with some being cleared for "topless nudity" or to be "scantily clad".[62] Crew members alleged that, during the shoot, Coppola pulled women to sit on his lap and kissed female extras to "get them in the mood". In response, executive producer Darren Demetre said, "Francis walked around the set to establish the spirit of the scene by giving kind hugs and kisses on the cheek to the cast and background players. It was his way to help inspire and establish the club atmosphere ... I was never aware of any complaints of harassment or ill behaviour during the course of the project."[10] When asked about the accusations, Coppola said, "My mother told me that if you make an advance toward a woman, it means you disrespect her, and the girls I had crushes on, I certainly didn't disrespect them." He also said a photo existed of a "girl" he kissed on the cheek that her father had taken, adding, "I knew her when she was nine. I'm not touchy-feely. I'm too shy."[63]

Videos of the encounters at the Tabernacle surfaced in July 2024, with sources telling Variety that Coppola had often inadvertently inserted himself into frame while interacting with extras and had announced on a microphone after multiple takes, "Sorry, if I come up to you and kiss you. Just know it's solely for my pleasure." Another source mentioned that, "Because Coppola funded it there was no HR department to keep things in check." Intimacy coordinators were not on set when the scene was shot and bystanders were reportedly told by senior crew members that they were not authorized to share recordings of the encounters because of non-disclosure agreements.[62] Days later, extras in the videos spoke out. Rayna Menz denounced the accusations against Coppola of inappropriate behavior, stating, "He did nothing to make me or for that matter anyone on set feel uncomfortable."[64] Meanwhile, Lauren Pagone said, "I was in shock. I didn't expect him to kiss and hug me like that. I was caught off guard," and expressed frustration with Menz' statement: "You can't speak for anyone but yourself. My experience was different." Another crew member alleged that Coppola kissed multiple women after calling "cut" for a different scene involving a New Year's Eve party that ended with kisses: "The women that I saw being kissed did not see him coming. He just basically grabbed them and planted the kiss on them without any kind of consent."[65]

Post-production

[edit]In March 2003, Coppola handwrote a letter to Osvaldo Golijov, asking him to compose a symphony that would have dictated the film's rhythm.[3]: 20 [66] They would go on to collaborate on Youth Without Youth, Tetro, and Twixt before returning to complete Megalopolis. Golijov wanted the score to blur the line between music and sound design. Given the ambiguity surrounding how the city and music of Rome sounded, he relied on Hollywood portrayals and composed a Roman suite inspired by Miklós Rózsa's score for Ben-Hur (1959). Coppola also asked Golijov to write a love theme in the vein of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's composition Romeo and Juliet (1870).[3]: 20–21 In February 2024, Coppola recorded the score with the Budapest Art Orchestra in Budapest, Hungary.[67]

Postproduction was completed at the All-Movie Hotel, where some reshoots were also held.[68] Cam McLauchlin and Glen Scantlebury edited the film, Coppola having contacted McLauchlin after seeing his work on Nightmare Alley (2021). McLauchlin defined Coppola's style as theatrical, incorporating theater warm-up techniques. The scene where Cesar and Julia play tug of war on an imaginary rope was a rehearsal take that inspired them to embrace the script's eccentricity. McLauchlin and Scantlebury were tasked to work on scenes independently but transitioned toward collaboration after realizing they had enough time to keep pace with shooting and experiment with alternate versions. For a scene involving catwalks, Coppola handled disruptive noise levels by pre-recording the dialogue and playing it over a loudspeaker for wide shots. He then asked Driver to recite William Shakespeare's Hamlet, seemingly as a warm-up exercise. After filming wrapped, Coppola handed McLauchlin the first half of the film and Scantlebury the latter half, allowing them to trade sections to complete the edit. After Scantlebury moved on to another project, McLauchlin and Coppola continued editing for eight more months, during which Coppola suggested including the Shakespeare scene.[3]: 18–20

Themes

[edit]In 1999, Coppola described the film as setting the characters of the Catilinarian conspiracy in modern New York, saying, "In many ways what it's really about is a metaphor—because if you walk around New York and look around, you could make Rome there", and adding, "Ultimately what's at stake is the future, because it takes the premise that the future, the shape of things to come, is being determined today, by the interests that are vying for control ... we already know what happened to Rome. Rome became a fascist Empire. Is that what we're going to become?"[69] In 2008, he stated that his intention was to create a character similar to author Ayn Rand and an "enlightened" version of urban planner Robert Moses who would want to want to build a city within New York that was the model of what a city could be and where the priorities are all positive, adding that, "The problem is that the people in power don't want it to be that, because today they gain their power from hatred, disagreement, and conflict. When you talk about the Middle East, the people today—they don't want peace. The people on top, they like it the way it is."[26] In 2022, Coppola said the film had an optimistic look at humanity and the intuitive goodness in people even in a divided climate.[70] In 2024, Coppola said he "wondered whether the traditional portrayal of Catiline as 'evil' and Cicero as 'good' was necessarily true" and described the film as a commentary for the United States, under the belief that the country's founders borrowed from Roman law to develop their democratic government without a king.[8]

Release

[edit]Distribution

[edit]Coppola saw Megalopolis in full for the first time on an IMAX screen at the headquarters of IMAX Corporation in Playa Vista, Los Angeles. The film used camera technology for certain sequences that could cover an entire IMAX screen.[58] On March 28, 2024, a private screening was presented to distributors at the Universal CityWalk IMAX Theater in Hollywood. Coppola and his longtime attorney Barry Hirsch, a producer on the film, said they would not decide where to debut the film until they secured a distribution partner and a firm rollout plan.[71] However, the "muted" response to the screening made securing a distributor difficult. Studios weighed the return on investment, as Coppola expected a print-and-advertising (P&A) campaign of $80–100 million and for producers to receive half of the film's revenues.[58][72] A distribution veteran suggested that "If [Coppola] is willing to put up the P&A or backstop the spend, I think there would be a lot more interested parties."[58] Coppola's plan to forgo a sales agent was, thus, altered, with the company Goodfellas handling international sales; Le Pacte, for France, became the first to acquire distribution rights to a foreign market in late April.[73][74] Variety noted that individual territories were not given rights to paid video on demand or streaming options, "perhaps by design to lure a big streaming service" into buying the streaming rights after its theatrical run. On May 15, Variety reported on sources that said Coppola was seeking an "awards-savvy distributor", such as A24, to release Megalopolis in the fourth quarter of 2024 so it could have an awards season campaign, but that "some potential indie outfits" who saw the film did not envision "much Oscars potential beyond technical categories and [feared] that Coppola [would] be an overly demanding partner."[75]

On May 16, 2024, the 138-minute film premiered in competition at the 77th Cannes Film Festival.[76][77][78] During the film's Cannes press conference, Coppola criticized the studio system and likened a streaming option to a home video release, saying, "I fear that the film industry has become more a matter of people being hired to ... pay their debt obligations ... So it might be that the studios we knew for so long are not [going] to be here in the future anymore."[79][80] That same day, the film secured a limited global IMAX release, including in at least 20 cities in the United States regardless of distributor.[81] A month later, on June 17, Lionsgate Films acquired domestic distribution rights, scheduling a release for September 27, 2024.[82] The deal came after Coppola agreed to pay for marketing costs. Lionsgate is expected to play the film in more than 1,500 theaters, requiring a marketing budget of at least $15–20 million.[83] For its premium large format screenings, it will share IMAX screens with The Wild Robot before giving them up a week later to Joker: Folie à Deux.[84][85][86] The film will also screen at Roy Thomson Hall as part of the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival on September 9 and during the 72nd San Sebastián International Film Festival.[87][88][89] The private industry screening and the Cannes premiere had a person walk on stage in front of the projection screen and address the protagonist, Cesar, who seemingly breaks the fourth wall by replying in real time.[90] Jean Labadie, founder of the film's French distributor, Le Pacte, said in regards to replicating the moment, "We will work on that with every exhibitor in France to try to do it as many times as we can."[91] Lionsgate made a similar pledge in regards to the fourth wall break.[92]

Marketing

[edit]Tie-ins and documentary

[edit]Image Comics and Syzygy Publishing will distribute a graphic novel tie-in to the film written by Chris Ryall and with artwork by Jacob Phillips.[93] Ryall had direct input and liberty from Coppola while Phillips confirmed that he was "drawing this book (on and off) since December 2022" and wrapped his part of the 148-page comic adaptation in July 2024; the screenplay and concept art was used as foundations for the graphic novel.[94] The late author Colleen McCullough, whose book series Masters of Rome (1990–2007) partially inspired Megalopolis, wrote the novelization of the film prior to her death in 2015.[95] The novels will accompany the film's release, along with a behind-the-scenes fly-on-the-wall documentary, Megadoc, by Mike Figgis that features interviews with cast members, Spike Lee, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Coppola's late wife Eleanor Coppola, who died in April 2024.[96][97][98] Coppola clarified that "all three projects are independent" of him but based on his "many scripts and ideas over the decades".[99]

Trailer controversy

[edit]On August 16, 2024, Lionsgate announced a partnership with the company Utopia (co-founded by Coppola's nephew, Robert Schwartzman)[100] on the stateside theatrical release, with the latter working on "specialty marketing, word-of-mouth, and non-traditional theatrical distribution initiatives" to target filmgoers.[101] On August 20, Lionsgate shared a theatrical poster that featured Driver's character holding a t-square vertically. Roger Friedman of Showbiz411 felt the tool's resemblance to a lightsaber may have been intentional, given Driver's role as Kylo Ren in the Star Wars sequel trilogy (2015–2019).[102]

The following day, Lionsgate released a trailer that featured snippets of negative reviews for Coppola's The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, and Bram Stoker's Dracula followed by 90 seconds of footage from Megalopolis, all accompanied by Fishburne's narration that "True genius is often misunderstood" and "One filmmaker has always been ahead of his time" before naming the film "an event nothing can prepare you for". The unconventional tactic, according to Rolling Stone's Daniel Kreps, attempted to combat the film's mixed reception at Cannes by pointing out "similarly misguided critical assessments of Coppola's previous masterpieces".[103] Oli Welsh of Polygon called it "defensive", with the implication that viewers "should ignore the reviews and go see it before it is inevitably reevaluated as a visionary classic",[104] while Mary Kate Carr from The A.V. Club described it as "pretty clever", noting that it highlighted similarities between Coppola and the film's protagonist.[105] However, Vulture's Bilge Ebiri and soon after other publications verified that the blurbs cited in the trailer were fabricated, including those credited to Vincent Canby, Roger Ebert, Owen Gleiberman, Pauline Kael, Stanley Kauffmann, Rex Reed, Andrew Sarris, and John Simon. While some of their opinions were indeed negative (excluding Kael's positive review for The Godfather and Ebert's for Dracula), the quotes were fake.[106][107] As a result, Lionsgate took down the trailer the same day they published it (after it had accumulated 1.3 million views)[108] and issued an apology.[109] Two days later, Lionsgate fired Eddie Egan, the marketing consultant who delivered the quotes, citing "an error in properly vetting and fact-checking the phrases". Variety suggested that the quotes may have been produced by generative artificial intelligence.[110]

Reception

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 53% of 69 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 4.7/10.[111] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 59 out of 100, based on 28 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[112]

The early industry screening resulted in reactions considered divisive while some were mixed, though others were primarily of general bewilderment.[113] Many attendees praised LaBeouf's performance.[58][114] Deadline Hollywood's Mike Fleming Jr. praised the film's runtime and ambition, calling it "an epic and highly visual fable that plays perfectly on an IMAX screen".[71] Fellow director Gregory Nava said, "It is an unbelievable, astonishing film, and [Coppola] is pushing the boundaries of cinema ... [Coppola] has used visual effects, and things that before have simply been limited to superhero movies, in a way to evoke other kinds of emotions."[115] The film was additionally described as reminiscent of the literary works of Ayn Rand, particularly The Fountainhead (1943), and the films Metropolis (1927) and Caligula (1979).[116][117] Many journalists expressed fascination and concern regarding its success, labeling it a potential critical and box-office failure, while debating whether it could be Coppola's masterpiece.[118] Others criticized studio heads and executives who anonymously yet publicly lambasted the film.[119][120] Coppola optimistically compared the polarizing responses to the initial reactions to Apocalypse Now four decades prior,[115] and insinuated that the "unnamed sources... probably weren't at the screening and may not exist."[121]

The film received a similarly polarized response from critics at the Cannes Film Festival.[122] Variety's Matt Donnelly and Ellise Shafer summarized, "Though reactions have been mixed, the film was undoubtedly jam-packed with scenes that ranged from visionary to just plain puzzling."[123]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chang, Justin (May 16, 2024). "The Madly Captivating Urban Sprawl of Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 8, 2024. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Piña, Christy (May 4, 2024). "Adam Driver Controls Time in First-Look Clip for Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis: Productions Notes" (PDF). Cannes Film Festival. May 13, 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wise, Damon (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis Review: Francis Ford Coppola's Mad Modern Masterwork Reinvents the Possibilities of Cinema – Cannes Film Festival". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis is a Work of Absolute Madness". Vulture. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Macnab, Geoffrey (May 17, 2024). "Megalopolis, Cannes review: Francis Ford Coppola's $120M Self-Funded Epic is No Car Crash". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Rooney, David (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis Review: Francis Ford Coppola's Passion Project Starring Adam Driver is a Staggeringly Ambitious Big Swing, if Nothing Else". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Breznican, Anthony (April 30, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis: An Exclusive First Look at the Director's Retro-Futurist Epic". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on April 30, 2024. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c Romberger, James H. (September 2017). The Conflict of Progressive and Conservative Tendencies in the Film Work of Steranko (M.A. thesis). CUNY Academic Works. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Rose, Steve (May 14, 2024). "'Has this guy ever made a movie before?' Francis Ford Coppola's 40-year battle to film Megalopolis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ Cowie, Peter (April 20, 2001). The Apocalypse Now Book. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81046-8. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Schumacher, Michael (October 19, 1999). Francis Ford Coppola: A Filmmaker's Life. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 0-517-70445-5. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Thomson, David; Gray, Lucy (September–October 1983). "Idols of the King" (PDF). Film Comment. 19 (5): 61–75. JSTOR 43452924. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Chown, Jeffrey (May 20, 1988). Hollywood Auteur: Francis Coppola. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-92910-8. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Clarke, James (January 1, 2003). Virgin Film: Coppola. Virgin Pub. ISBN 0-7535-0866-4. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Cowie, Peter (August 22, 1994). Coppola: A Biography. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80598-1. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Cowie, Peter (January 1, 1997). The Godfather Book. Gardners Books. ISBN 0-571-19011-1. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Knowles, Harry (May 8, 2007). "Harry sits down in Austin with Francis Ford Coppola and talks Youth Without Youth, Seventies film, Wine, Tetro, and the Coppolas". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Boorman, John (January 1, 1994). Projections 3: Film-Makers on Film-Making. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-571-17047-1. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ Handy, Bruce (April 1, 2010). "The Liberation of Francis Ford Coppola". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Zilko, Christian (June 25, 2023). "Jon Hamm Left Megalopolis Table Read Thinking 'I Don't Know How He's Gonna Make This Movie'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 12, 2024. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Macnab, Geoffrey (September 26, 2002). "Back from the brink". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 1, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Archerd, Army (July 17, 2001). "Coppola prepping Megalopolis". Variety. Archived from the original on April 1, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c Lyons, Charles (October 16, 2001). "Megalopolis plans shifted". Variety. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Fleming, Mike Jr. (May 13, 2019). "Francis Ford Coppola: How Winning Cannes 40 Years Ago Saved Apocalypse Now, Making Megalopolis, Why Scorsese Almost Helmed Godfather Part II & Re-Cutting Three Past Films". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 16, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Jacobson, Harlan (January–February 2008). "Brief Encounters: Francis Ford Coppola". Film Comment. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- ^ Kerch, Steve (November 5, 2003). "Coppola: The City and His Dreams, Famed Director Readies Vision of Future Megalopolis". Urban Land Institute. Archived from the original on December 7, 2003. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

The director has already shot about 70 hours of film in Manhattan that will serve as background for the movie.

- ^ a b Delorme, Stéphane (October 1, 2010). Francis Ford Coppola. Cahiers du Cinéma. ISBN 978-2866425937. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Vaucher, Andrea R.; Harris, Dana (February 24, 2002). "Zoetrope, Myriad plan 3 pics". Variety. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Keegan, Rebecca (November 7, 2007). "Coppola, Take 2". Time. Archived from the original on April 1, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ Buchanan, Kyle (June 3, 2009). "Francis Ford Coppola to Movieline: 'Godfather Never Should Have Had More Than One Movie'". Movieline. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (April 3, 2019). "Francis Ford Coppola Ready to Make Megalopolis and is Eyeing Cast". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ Murray, Tom (May 17, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola says children 'don't need a fortune' after selling business to fund Megalopolis". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 23, 2024. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ Quackenbush, Jeff (June 24, 2021). "Francis Ford Coppola selling Sonoma County wineries to Napa's Delicato Family Wines". North Bay Business Journal. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (August 31, 2021). "Francis Coppola, A Gambling Maverick Moviemaker Who Won Big, Betting on Star Cast for Epic Megalopolis". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ a b Gardner, Chris (May 13, 2024). "Megalopolis Lead Nathalie Emmanuel on Sealing Role in a Playful Zoom with Francis Ford Coppola". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Ritman, Alex (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis Star Nathalie Emmanuel Talks Working with Francis Ford Coppola on His Mysterious Sci-Fi Drama: Like 'Being Part of an Orchestra and He's the Conductor'". Variety. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Blyth, Antonia (May 13, 2024). "Cannes Cover Story: Aubrey Plaza Says Francis Coppola 'Doesn't Need My Defense', Reveals the 'Collaboration and Experimentation' of Megalopolis". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ Gardner, Chris (March 3, 2022). "Francis Ford Coppola Explains Why He's Spending His Own $120M on Megalopolis". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Friedman, Roger (March 21, 2022). "Exclusive: Oscar Isaac Passes on Godfather Director Francis Ford Coppola's $120 Mil Megalopolis, Director Wants to Shoot This Fall". Showbiz411. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (May 12, 2022). "Francis Coppola Sets Megalopolis Cast: Adam Driver, Forest Whitaker, Nathalie Emmanuel, Jon Voight & Filmmaker's Apocalypse Now Teen Discovery Laurence Fishburne". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Dagan, Carmel (July 8, 2022). "James Caan, The Godfather and Misery Star, Dies at 82". Variety. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (August 22, 2022). "Aubrey Plaza Joins Adam Driver in Francis Coppola's Megalopolis". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (August 31, 2022). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Casts Talia Shire, Shia LaBeouf, Jason Schwartzman, and More". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (October 4, 2022). "Francis Coppola Sets Final Casting for Epic Megalopolis; Film Shooting This Fall in Georgia". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ Hailu, Selome (June 14, 2024). "Hannah Einbinder & Chloe Fineman – Actors on Actors (Full Conversation)". Variety. Event occurs at 25:20. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Waters, Jagger (January 17, 2020). "A Women-Led Performing Arts Collective Said Goodbye to 2019 with a Wake at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery". Vogue. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 23, 2023). "Giancarlo Esposito Joins Cast of Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Coppola, Francis Ford (December 8, 2023). "@gracevanderwaal is a multi-talented songwriter, musician, and actor whom I am so lucky to have worked with on @megalopolisfilm". Instagram. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ Rinder, Grant (January 22, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Might Actually Come Out This Year. Here's Everything We Know". GQ. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Bergeson, Samantha (September 28, 2022). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Will Debut Never-Before-Seen Film Technology". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Klawans, Justin (September 28, 2022). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis to Film at Prysm Stages in Atlanta Using Groundbreaking Technology". Collider. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Masters, Kim; Feinberg, Scott; Couch, Aaron (January 9, 2023). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis in Peril Amid Ballooning Budget, Crew Exodus (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 9, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ^ DeLucia, Francesca (July 10, 2023). "Mike Figgis, 'vi porto nella Megalopolis di Coppola'" [Mike Figgis, 'I'll take you to Coppola's Megalopolis']. Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (in Italian). Archived from the original on July 10, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c Kramon, Charlotte (July 17, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis wrapped at this Georgia hotel. Soon, it'll be open for business". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ Bergeson, Samantha (July 10, 2024). "You Can Now Stay Where Megalopolis Was Completed: Introducing Coppola's All-Movie Hotel". IndieWire. Archived from the original on July 10, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Valinsky, Michael (August 3, 2022). "A Cinematographer's Life with Mihai Malaimare Jr". The Making of (Podcast). Archived from the original on December 14, 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Abramovitch, Seth; Masters, Kim; McClintock, Pamela (April 8, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Faces Uphill Battle for Mega Deal: 'Just No Way to Position This Movie'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 13, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (August 31, 2023). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Lands Interim Agreement from SAG-AFTRA". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ Bergeson, Samantha (January 5, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola Confirms Megalopolis Early 2024 Release: 'Wait and See'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on January 6, 2024. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 10, 2023). "Francis Ford Coppola: No Truth to Apocalypse on Megalopolis". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 10, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Lang, Brent; Siegel, Tatiana (July 26, 2024). "Video of Francis Ford Coppola Kissing Megalopolis Extras Surfaces as Crew Members Detail Unprofessional Behavior on Set (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on July 26, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (June 6, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola: 'You Can't Be an Artist and Be Safe'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2024. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (July 30, 2024). "Salacious Variety Megalopolis Video a Sham, Says Rayna Menz, the Extra Shown with Francis Coppola". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Siegel, Tatiana; Lang, Brent (August 2, 2024). "Extra Kissed by Francis Ford Coppola in Megalopolis Set Video Breaks Silence: 'I Was in Shock'". Variety. Archived from the original on August 3, 2024. Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ Church, Michael (February 14, 2006). "Osvaldo Golijov: Composing the soundtrack for a Coppola movie". The Independent. Archived from the original on April 1, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ "Director Francis Ford Coppola Makes a Splash during Stay in Budapest". Hungary Today. February 18, 2024. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ Tangcay, Jazz (July 10, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola Opens Hotel for Filmmakers and Public in Georgia With On-Site Post-Production Facilities (Exclusive)". Variety. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Coppola, Francis Ford (1999). "Writing and Directing The Conversation: A Talk with Francis Ford Coppola". Scenario (Interview). Vol. 5, no. 1. Interviewed by Ann Nocenti. Archived from the original on December 15, 2000. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (March 25, 2022). "From The Godfather Trilogy to American Graffiti, Patton, The Conversation & Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola Shares His Oscar Memories". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ a b Fleming, Mike Jr. (March 28, 2024). "Francis Coppola's Megalopolis Screened for First Time Today for Distributors at CityWalk IMAX". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 30, 2024. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Keslassy, Elsa (April 23, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Nears French Distribution Deal with Indie Banner Le Pacte". Variety. Archived from the original on April 24, 2024. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Kay, Jeremy (April 30, 2024). "Goodfellas boards international sales on Francis Ford Coppola's Cannes Selection Megalopolis (exclusive)". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on May 1, 2024. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ Goodfellow, Melanie (May 22, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Cannes Contender Megalopolis Inks Another Raft of International Distribution Deals". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Lang, Brent; Siegel, Tatiana; Donnelly, Matt (May 15, 2024). "Can Cannes Save Megalopolis? Francis Ford Coppola Prepares to Unveil His $120 Million Epic as Controversy Builds". Variety. Archived from the original on May 15, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (April 9, 2024). "Francis Coppola's Megalopolis Locks Competition Slot at 77th Cannes Film Festival: The Dish". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy; D'Alessandro, Anthony; Bamigboye, Baz (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis Debuts at Cannes with 7-Minute Standing Ovation". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 21, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis: What the Critics are Saying". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ "Megalopolis by Francis Ford Coppola – Press Conference". Cannes Film Festival. May 17, 2024. Event occurs at 31:45. Archived from the original on May 19, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (May 17, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola on Movie Industry: 'Streaming is What We Used to Call Home Video', But Major Studios May Become Extinct – Cannes". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 8, 2024. Retrieved June 8, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony; Tartaglione, Nancy (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis IMAX Global Release Will Be Limited; Release Date Contingent on U.S. Distribution but Late September Eyed for IMAX in 20 US Cities; Coppola Live Event Planned – Cannes". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Welk, Brian (June 17, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis to Be Released This September by Lionsgate". IndieWire. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Couch, Aaron; Masters, Kim (June 20, 2024). "How Francis Ford Coppola's Embattled Megalopolis Finally Landed a Distributor". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 20, 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 22, 2024). "DreamWorks Animation's The Wild Robot Will Go One Week Later in the Fall". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on July 4, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca (June 17, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Lands at Lionsgate for U.S. Release After Divisive Cannes Premiere". Variety. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (June 17, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis to be Released by Lionsgate in U.S." Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 18, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (August 13, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis, Films from Pedro Almodovar and Max Minghella Join Toronto Film Fest". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 13, 2024. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ "Megalopolis". Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on August 13, 2024. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (August 16, 2024). "Cannes Highlights Anora, Megalopolis, Emilia Pérez Set for San Sebastian's Perlak Sidebar". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ LeBeau, Ariel (May 22, 2024). "Megalopolis is Even Wilder Than You Might've Heard". GQ. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas; Ntim, Zac; Goodfellow, Melanie (May 19, 2024). "Megalopolis: Will Distributors Replicate One of the Movie's Most Talked About Moments? 'We'll Try as Many Times as We Can', Says France's Le Pacte". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 19, 2024. Retrieved May 19, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (June 17, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis to Be Released by Lionsgate in U.S." Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 18, 2024. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Powell, Nancy (March 25, 2023). "Syzygy announces Megalopolis, Francis Ford Coppola graphic novel at WonderCon". Comics Beat. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (July 9, 2024). "Jacob Phillips Finishes Adapting Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on July 10, 2024. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Barsanti, Sam (September 3, 2023). "Francis Ford Coppola teases a Megalopolis novelization from Colleen McCullough—who died in 2015". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on May 7, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ Newman, Nick (January 10, 2023). "Francis Ford Coppola and Adam Driver Respond to Megalopolis Rumors; Mike Figgis Plans a Behind-the-Scenes Documentary". The Film Stage. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ @TheFilmStage (October 11, 2023). "Mike Figgis has interviewed Spike Lee and George Lucas for his documentary on Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis" (Tweet). Retrieved May 15, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Bamigboye, Baz (May 21, 2024). "Breaking Baz @ Cannes: Mike Figgis Mourns Fred Roos, Details Fly-on-the-Wall Coppola Documentary Megadoc; Festival Party Talk Through the Night with Blanchett, Schrader & Oldman". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Echebiri, Chike (May 7, 2024). "Megalopolis: Cast, Plot, Filming Details, and Everything We Know So Far About Francis Ford Coppola's Passion Project". Collider. Archived from the original on May 21, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ Zilko, Christian (August 16, 2024). "The Next Generation of Coppolas Will Help the Next Generation of Film Fans Discover Megalopolis". IndieWire. Archived from the original on August 17, 2024. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (August 16, 2024). "Megalopolis Lionsgate Theatrical Release to Get Boost from Utopia". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ Friedman, Roger (August 20, 2024). "New Official Poster for Coppola's Megalopolis A Riff on or Rip Off of Star Wars Light Saber?". Showbiz411. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (August 21, 2024). "Megalopolis: New Trailer Says Critics Were Wrong About Godfather, Dracula, and Now This Polarizing Epic". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Welsh, Oli (August 21, 2024). "This might be the most defensive movie trailer of all time". Polygon. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Kate Carr, Mary (August 21, 2024). "Megalopolis' first full trailer insists it will stand the test of time". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (August 21, 2024). "Did the Megalopolis Trailer Use Fake Movie Critic Quotes?". Vulture. Archived from the original on August 21, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Stephan, Katcy (August 21, 2024). "Megalopolis Trailer Fabricates Quotes From Famous Movie Critics". Variety. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Aguiar, Annie (August 21, 2024). "Studio Pulls Megalopolis Trailer Featuring Fake Review Quotes". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (August 21, 2024). "Lionsgate Recalling Megalopolis Trailer Amid Fabricated Quote Controversy: 'We Screwed Up'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Maddaus, Gene; Stephan, Katcy (August 23, 2024). "Megalopolis Trailer's Fake Critic Quotes Were AI-Generated, Lionsgate Drops Marketing Consultant Responsible For Snafu". Variety. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ "Megalopolis". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ "Megalopolis". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Wells, Jeffrey (March 28, 2024). "Coppola's Megalopolis Screens for Industry Elite at Universal IMAX". Hollywood Elsewhere. Archived from the original on April 16, 2024. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- Ruimy, Jordan (March 28, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis Screens: 'Startling', 'Experimental', 'Avant Garde'". World of Reel. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- Northrup, Ryan (March 29, 2024). "'Unflinching in How Bats**t Crazy It Is': Megalopolis Early Reactions Tease Coppola's Truly Bizarre Epic". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- Ruimy, Jordan (March 29, 2024). "More Megalopolis Reactions: 'Batsh*t Crazy', 'Tough Sell', 'Baffling'". World of Reel. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- Bailey, Micah (March 30, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola's $120M Sci-Fi Just Got a Lot More Exciting & Worrying for the Same Reason". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on March 30, 2024. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- Ruimy, Jordan (April 1, 2024). "More Megalopolis Reactions: 'Downright Confounding' and 'Fit for a Museum'". World of Reel. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ Belloni, Matthew (March 29, 2024). "What I'm Hearing: Netflix Wants NBA; Shari's Junk Debt; & Streaming Micro Wars". Puck. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Holmes, Helen (April 10, 2024). "Francis Ford Coppola Responds to Megalopolis Uproar: Exactly What Happened with Apocalypse Now". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on April 11, 2024. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ Northrup, Ryan (March 29, 2024). "'Unflinching in How Bats**t Crazy It Is': Megalopolis Early Reactions Tease Coppola's Truly Bizarre Epic". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Welk, Brian (April 2, 2024). "As Francis Ford Coppola Seeks Megalopolis Distribution, 'Everything is on the Table'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Johnston, Dais (April 30, 2024). "Will Francis Ford Coppola's Epic Ambitions Ruin His Potential Masterpiece?". Inverse. Archived from the original on May 15, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- Gentile, Dan (May 8, 2024). "Coppola's Megalopolis is the riskiest movie of the year. The first trailer just dropped". SFGate. Archived from the original on May 15, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- Lethbridge, Tommy (May 11, 2024). "We're Worried About Francis Ford Coppola's New Movie After Watching the First Clip". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on May 12, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- Valentine, Claire (May 15, 2024). "Will Megalopolis Be a Visionary Hit or a Major Miss?". W Magazine. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- Barber, Nicholas (May 15, 2024). "Why 'wild' sci-fi epic Megalopolis could be Francis Ford Coppola's $120m mistake". BBC. Archived from the original on May 15, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- Lodge, Guy (May 18, 2024). "The Fall Guy to Megalopolis: Is 2024 the Year of the Box-Office Megaflop?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (April 11, 2024). "Hollywood Is Doomed If There's No Room for Megalopolis". Vulture. Archived from the original on April 30, 2024. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ Macnab, Geoffrey (May 10, 2024). "Hollywood can't help being suspicious about Francis Ford Coppola – Megalopolis isn't going to change that". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 10, 2024. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

- ^ Wasson, Sam (May 17, 2024). "The View from Here". Air Mail. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Wiseman, Andreas (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis: What the Critics are Saying". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- Yuan, Jada (May 16, 2024). "Coppola's Megalopolis sparks Cannes frenzy and furious debate". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- Sun, Michael (May 16, 2024). "'Bafflingly shallow' or 'staggeringly ambitious'? Francis Ford Coppola's Megalopolis splits critics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- Bentz, Adam (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis, Francis Ford Coppola's Self-Funded Sci-Fi Epic, Fiercely Divides Critics". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- Ruimy, Jordan (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis: Boos, and Some Cheers, Greet Coppola's Ambitious WTF Statement [Cannes]". World of Reel. Archived from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- Protheroe, Ben (May 20, 2024). "10 Reasons Megalopolis' Reviews Are So Strongly Divided". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ Shafer, Ellise; Donnelly, Matt (May 16, 2024). "Megalopolis: The 5 Most WTF Moments from Francis Ford Coppola's Sci-Fi Epic". Variety. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

External links

[edit]- 2024 films

- 2024 independent films

- 2020s American films

- 2020s English-language films

- Advertising and marketing controversies in film

- American epic films

- American science fiction drama films

- American independent films

- American Zoetrope films

- Films about architects

- Films directed by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films produced by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films scored by Osvaldo Golijov

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot at Trilith Studios

- Films shot in Atlanta

- Film productions suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Films with screenplays by Francis Ford Coppola

- Lionsgate films