Mohawk people: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 173.209.108.173 (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG (HG) |

|||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

[[File:Hudsonmap.png|thumb|map of Mohawk River]] |

[[File:Hudsonmap.png|thumb|map of Mohawk River]] |

||

In the [[Mohawk language]], the people say that they are from '''Kanien'kehá:ka''' or "Flint Stone Place." As such, the Mohawks were extremely wealthy traders as other nations in their confederacy needed their flint for tool making. Their Algonquian-speaking neighbors (and competitors), the People of "'''Muh-heck Heek Ing'''" (Food Area Place), a people who the Dutch called "[[Mohicans]]" or "Mahicans," called the People of Ka-nee-en Ka "Maw Unk Lin" or "'''Bear People'''." The Dutch and heard and wrote this as "Mohawks." This is why the People of Kan-ee-en Ka are often referred to as "'''Mohawks'''." The Dutch also referred to the Mohawk as ''"Egils"'' or ''"Maquas."'' The [[French people|French]] adapted these terms as ''Aigniers'', ''Maquis'', or called them by the generic '''"Iroquois,"''' which is a French derivation of the [[Algonquian_peoples|Algonquian]] term for the Five Nations: '''"Snake People."''' |

In the [[Mohawk language]], the people say that they are from '''Kanien'kehá:ka''' or "Flint Stone Place." As such, the Mohawks were extremely wealthy traders as other nations in their confederacy needed their flint for tool making. Their Algonquian-speaking neighbors (and competitors), the People of "'''Muh-heck Heek Ing'''" (Food Area Place), a people who the Dutch called "[[Mohicans]]" or "Mahicans," called the People of Ka-nee-en Ka "Maw Unk Lin" or "'''Bear People'''." The Dutch and heard and wrote this as "Mohawks." This is why the People of Kan-ee-en Ka are often referred to as "'''Mohawks'''." The Dutch also referred to the Mohawk as ''"Egils"'' or ''"Maquas."'' The [[French people|French]] adapted these terms as ''Aigniers'', ''Maquis'', or called them by the generic '''"Iroquois,"''' which is a French derivation of the [[Algonquian_peoples|Algonquian]] term for the Five Nations: '''"Snake People."''' |

||

"ninjas of the forest" |

|||

==History since colonization== |

==History since colonization== |

||

Revision as of 16:40, 12 December 2013

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| English, Kanien’kéha, French, Mohawk Dutch, Other Iroquoian Dialects | |

| Religion | |

| Karihwiio, Kanoh'hon'io, Kahni'kwi'io, Christianity, Longhouse, Handsome Lake, Other Indigenous Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Seneca Nation, Oneida Nation, Cayuga Nation, Onondaga Nation, Tuscarora Nation, other Iroquoian peoples |

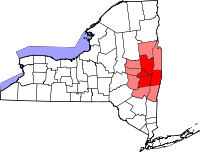

The Mohawk People are the most easterly tribe of the Iroquois Confederacy. They are the People of "Ka Nee-en Ka" (or "Flint Stone Place") and are an Iroquoian-speaking indigenous people of North America. They were historically based in the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York; their territory ranged to present-day southern Quebec and eastern Ontario. Their traditional homeland stretched southward of the Mohawk River, eastward to the Green Mountains of Vermont, westward to the border with the Oneida Nation's traditional homeland territory, and northward to the St Lawrence River. As original members of the Iroquois League, or Haudenosaunee, the Mohawk were known as the "Keepers of the Eastern Door". For hundreds of years, they guarded the Iroquois Confederation against invasion from that direction by tribes from the New England and lower New York areas. Mohawk religion is predominantly Animist. Their current settlements include areas around Lake Ontario and the St Lawrence River in Canada and New York. The People of Ka Nee-en Ka received their familiar name, "Mohawk," from the neighboring (and competing) People of Muh-heck Heek Ing (whom the Dutch called "Mohicans" or "Mahicans"). The Mohicans/Mahicans called them "Maw Unk Lin" or "Bear Place People." The Dutch heard and wrote, "Mohawk."

Origins of name

In the Mohawk language, the people say that they are from Kanien'kehá:ka or "Flint Stone Place." As such, the Mohawks were extremely wealthy traders as other nations in their confederacy needed their flint for tool making. Their Algonquian-speaking neighbors (and competitors), the People of "Muh-heck Heek Ing" (Food Area Place), a people who the Dutch called "Mohicans" or "Mahicans," called the People of Ka-nee-en Ka "Maw Unk Lin" or "Bear People." The Dutch and heard and wrote this as "Mohawks." This is why the People of Kan-ee-en Ka are often referred to as "Mohawks." The Dutch also referred to the Mohawk as "Egils" or "Maquas." The French adapted these terms as Aigniers, Maquis, or called them by the generic "Iroquois," which is a French derivation of the Algonquian term for the Five Nations: "Snake People." "ninjas of the forest"

History since colonization

First contact with European settlers

The Mohawk encountered both the Dutch, who went up the Hudson River for trade near present-day Albany, New York, and the French, who came into their territory from Canada, both for trade and with Jesuit missionaries teaching about Christianity.

In 1614, the Dutch opened a trading post at Fort Nassau, New Netherland. The Dutch initially traded for furs with the local Mahican. In 1628, the Mohawk tribe defeated the Mahican, who retreated to Connecticut. The People of Ka-nee-en Ka (Mohawks) gained a near-monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch by not allowing the nearby Algonquian-speaking tribes to the north or east to trade with them. The Dutch also established trading posts at present-day Schenectady and Schoharie, further west in the Mohawk Valley and closer to Mohawk settlements.

The Mohawk and Dutch became allies. Their relations were peaceful even during the periods of Kieft's War and the Esopus Wars, when the Dutch fought localized battles with other tribes. The Dutch trade partners equipped the Mohawk with guns to fight against other nations allied with the French, including the Ojibwe, Huron-Wendat, and Algonquin. In 1645 the Mohawk made peace with the French.

During the Pequot War (1634–1638), the Algonquian Indians of New England sought an alliance with the Mohawk. The Mohawk refused the alliance, killing the Pequot sachem Sassacus, who had come to them for refuge.

In the winter of 1651, the Mohawk attacked to the southeast and overwhelmed Algonquians in the coastal areas. They took between 500-600 captives. In 1664, the Pequot of New England killed a Mohawk ambassador, starting a war that resulted in the destruction of the Pequot. The Mohawks also attacked other members of the Pequot confederacy, in a war that lasted until 1671.[citation needed]

In 1666, the French attacked the Mohawk in the central New York area, burning all the Mohawk villages and their stored food supply. One of the conditions of the peace was that the Mohawks accept Jesuit missionaries. Beginning in 1669, missionaries attempted to convert many Mohawks from paganism to Christianity and relocate to two mission villages near Montreal. These Mohawks became known as the Kahnawake (also spelled Caughnawaga) and they became allies of the French. Many converted to Catholicism at Kahnawake, the village named after them.

One of the most famous Catholic Mohawks was Kateri Tekakwitha. She was later beatified and was canonized in October 2012 as the first Native American Catholic saint.

After the fall of New Netherland to England in 1649, the Mohawk in New York became English allies. During King Philip's War, Metacom, sachem of the warring Wampanoag Pokanoket, decided to winter with his warriors near Albany in 1675. Encouraged by the English, the Mohawk attacked and killed all but 40 of the 400 Pokanokets.

From the 1690s, the Mohawk in the New York colony were appealed to convert by Protestant missionaries. Many were baptized with English surnames, while others were given both first and surnames in English.

During the era of the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War), Anglo-Mohawk partnership relations were maintained by men such as Sir William Johnson in New York (for the British Crown), Conrad Weiser (on behalf of the colony of Pennsylvania), and Hendrick Theyanoguin (for the Mohawk). The Albany Congress of 1754 was called in part to repair the damaged diplomatic relationship between the British and the Mohawk.

American Revolutionary War

During the second and third quarters of the 18th century, most of the Mohawk in the Province of New York lived along the Mohawk River at Canajoharie. A few lived at Schoharie, and the rest lived about 30 miles downstream at the Ticonderoga Castle, also called Fort Hunter. These two major settlements were traditionally called the Upper Castle and the Lower Castle. The Lower Castle was almost contiguous with Sir Peter Warren's Warrensbush. Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, built his first house on the north bank of the Mohawk River almost opposite Warrensbush.

Because of unsettled conflicts with colonists encroaching into their territory in the Mohawk Valley and outstanding treaty obligations to the British Crown, the Mohawk were among the four Iroquois tribes that allied with the British during the American Revolutionary War. Joseph Brant acted as a war chief and successfully led raids against British and German colonists in the Mohawk Valley.

A few prominent Mohawks, such as the sachem Little Abraham at Fort Hunter, remained neutral throughout the war. Joseph Louis Cook, a veteran of the French and Indian War and ally of the rebels, offered his services to the Americans, receiving an officer's commission from the Continental Congress. He led Oneida warriors against the British. During this war, Johannes Tekarihoga was the civil leader of the Mohawk. He died about 1780. Catherine Crogan, a clan mother and wife of Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant, named her brother Henry Crogan as the new Tekarihoga.

After the Revolution

After the American victory, the British ceded their claim to land in the colonies, and the Americans forced their allies, the Mohawk and others, to give up their territories in New York. Most of the Mohawk migrated to Canada, where the Crown gave them land in compensation. The Mohawks at the Upper Castle fled to Fort Niagara, while most of those at the Lower Castle fled to Montreal.

Joseph Brant led a large group of Iroquois out of New York to what became the reserve of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario. Another Mohawk war chief, John Deseronto, led a group of Mohawks to the Bay of Quinte. Other Mohawks settled in the vicinity of Montreal and upriver, joining the established communities (now reserves) at Kahnawake, Akwesasne, and Kanesatake.

On November 11, 1794, representatives of the Mohawks (along with the other Iroquois nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States, which allowed them to own land there.

The Mohawk fought with the British against the United States in the War of 1812.

Mohawk communities today

Members of the Mohawk tribe now live in settlements in northern New York State and southeastern Canada. Many Mohawk communities have two sets of chiefs, who are in some sense competing governmental rivals. One group are the hereditary chiefs nominated by Clan Mother matriarchs in the traditional Mohawk fashion; the other are the elected chief and councilors, with whom the Canadian and U.S. governments usually prefer to deal exclusively. These are grouped below by broad geographical cluster, with notes on the character of community governance found in each.

- Northern New York:

- Kanièn:ke(Ganienkeh) "Place of the flint". Traditional governance.

- Kana'tsioharè:ke "Place of the washed pail". Traditional governance.

- Along the St Lawrence:

- Ahkwesásne(St. Regis, New York and Canada) "Where the partridge drums". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Ka'nehsatà:ke(Oka) "Where the snow crust is". Canada, traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Kahnawà:ke "On the rapids". Canada, traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Southern Ontario:

- Kenhtè:ke(Tyendinaga) "On the bay". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Wáhta(Gibson) "Maple tree". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Ohswé:ken(Six Nations of the Grand River) "???". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections. Mohawks also form the majority on this Iroquois Six Nations reserve. There are also Mohawk Orange Lodges in Canada.

Since the 1980s, Mohawk politics have been driven by factional disputes over gambling, land claims, traditional government jurisdiction, taxation, and the Indian Act.

Mohawk ironworkers in New York

New York City has a Mohawk community founded by construction workers for bridges and skyscrapers of Mohawk and other Iroquois origin. They worked from the 1930s to the 1970s on special labor contracts as specialists and participated in building the Empire State Building. The construction companies found that the Mohawk ironworkers did not fear heights or dangerous conditions. Their contracts offered lower than average wages to the First Nations people and limited labor union membership.[1]

The work and home life of Mohawk steelworkers was documented in Don Owen's 1965 National Film Board of Canada documentary High Steel.[2] A Mohawk community in Brooklyn called "Little Caughnawaga" had its heyday from the 1920s to the 1960s. These Brooklyn Mohawk were mostly from Kahnawake, where they returned every summer.[3]

Approximately 200 Mohawk iron workers (out of 2000 total iron workers at the site) have contributed to rebuilding the One World Trade Center. They typically drive the 360 miles from the Kahnawake reserve on the St. Lawrence River in Quebec to work the week in lower Manhattan, and then return on the weekend to be with their families. A selection of portraits of these Mohawk iron workers were featured in an online photo essay for Time Magazine in September 2012.[4]

Casinos

Both the elected chiefs and the controversial Warrior Society have encouraged gambling as a means of ensuring tribal self-sufficiency on the various reserves or Indian reservations. Traditional chiefs have tended to oppose gaming on moral grounds and out of fear of corruption and organized crime. Such disputes have also been associated with religious divisions: the traditional chiefs are often associated with the Longhouse tradition, practicing consensus-democratic values, while the Warrior Society has attacked that religion and asserted independence. Meanwhile, the elected chiefs have tended to be associated (though in a much looser and general way) with democratic, legislative and Canadian governmental values.

On October 15, 1993, Governor Mario Cuomo entered into the "Tribal-State Compact Between the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe and the State of New York." The compact allowed the Tribe to conduct gambling, including games such as baccarat, blackjack, craps and roulette, on the Akwesasne Reservation in Franklin County under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA).

According to the terms of the 1993 compact, the New York State Racing and Wagering Board, the New York State Police and the St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Gaming Commission were vested with gaming oversight. Law enforcement responsibilities fell under the cognizance of the state police, with some law enforcement matters left to the tribe. As required by IGRA, the compact was approved by the United States Department of the Interior before it took effect. There were several extensions and amendments to this compact, but not all of them were approved by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

On June 12, 2003, the New York Court of Appeals affirmed the lower courts' rulings that Governor Cuomo exceeded his authority by entering into the compact absent legislative authorization and declared the compact void [1]. On October 19, 2004, Governor George Pataki signed a bill passed by the State Legislature that ratified the compact as being Nunc Pro Tunc, with some additional minor changes.[5]

In 2008 the Mohawk Nation was working to obtain approval to own and operate a casino in Sullivan County, New York, at Monticello Raceway. The U.S. Department of the Interior disapproved this action and even after the Mohawk gained Governor Eliot Spitzer's concurrence, subject to the negotiation and approval of either an amendment to the current compact or a new compact, rejected their application to take this land into trust.[6]

There are currently two legal cases pending. The State of New York has expressed similar objections in its responses to take land into trust for other Indian nations and tribes.[7] The other contends that the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act violates the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution as it is applied in the State of New York and in 2010 was pending in the United States District Court for the Western District of New York.[8]

Culture

Traditional Mohawk dress

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

The traditional hairstyle of the Mohawk, and other tribes of the Iroquois, was to remove the hair from the head by plucking (not shaving) tuft by tuft of hair until all that was left was a square of hair on the back crown of the head. The remaining hair was shortened so that three short braids of hair were created, and those braids were highly decorated. This is the true "Mohawk" hairstyle and not the Hollywood version taken from the Pawnee.

The women wore their hair long, often dressed with traditional bear grease, or tied back into a single braid. They often wore no covering or hat on their heads, even in winter.

By traditional dress, the women went topless in summer and wore a skirt of deerskin. In colder seasons, women wore a full woodland deerskin dress, and leather tied underwear. They wore puckered-seam, ankle-wrap moccasins. They wore several ear piercings adorned by shell earrings, and shell necklaces.

The women used a layer of smoked and cured moss as an insulating absorbent layer during menses, as well as simple scraps of leather. Later, they used cotton-linen pieces, in areas where colonists had provided such items through trade.[citation needed]

Mohawk men wore a breech cloth of deerskin in summer. In cooler weather, they added deerskin leggings and a full-piece deerskin shirt. They also wore several shell strand earrings, shell necklaces, long fashioned hair, and puckered seamed wrap ankle moccasins. The men carried a quill and flint arrow hunting bag, and had arm and knee bands.

During the summer, the Mohawk children traditionally wore nothing up to the ages of thirteen. Then ready for their warrior or woman rites of passage, they took on the clothing of adults.[citation needed]

Later dress after European contact combined some cloth pieces such as the males' ribbon shirt in addition to the deerskin clothing, and wool trousers and skirts. For a time many Mohawk people incorporated a combination of the older styles of dress with newly introduced forms of clothing.

According to author Kanatí:ios in Rotinonhsión:ni Clothing and & Other Cultural Items, Mohawks as a part of the Rotinonhsión:ni Confederacy "traditionally used furs obtained from the woodland, which consisted of elk and deer hides, corn husks, and they also wove plant and tree fibers to produce [the] clothing". Later, sinew or animal gut was cleaned and prepared as a thread for garments and footwear and was threaded to porcupine quills or sharp leg bones to sew or pierce eyeholes for threading. Clothing dyes were obtained of various sources such as berries, tree barks, flowers, grasses, sometimes fixed with urine.[citation needed] Durable clothing that was held by older village people and adults was handed down to others in their family sometimes as gifts, honours, or because people had outgrown them.

Mohawk clothing was sometimes reminiscent of designs from trade with neighboring First Nation tribes, and more closely resembled that of other Six Nations confederacy nations; however, much of the originality of the Mohawk nation peoples' style of dress was preserved as the foundation of the style they wore.

Marriage

The Mohawk Nation people have a matrilineal kinship system, with descent and inheritance passed through the female line. Much respect is given to the woman because she is the head of the household and controls its property.[citation needed] They hold marriage as a great commitment that should be nurtured and respected. Mohawk Nation wedding ceremonies are conducted by a high-ranking man or by couple's choice. The marrying couple unite in a lifelong relationship.

The traditional marriage ceremony included a day of celebration for the newlyweds, a formal oration by a nobleman of the woman's clan, community dancing and feasting, and gifts of respect and honour by community members. Traditionally these gifts were practical items that the couple would use in daily life.

For wedding clothing, they wore white rabbit leathers and furs with personal adornments, usually made by their families. The "Rabbit Dance Song" and other social dance songs were sung by the men, where they used gourd rattles and later cow-horn rattles. In the "Water Drum", other well-wishing couples participated in the dance with the couple. The meal commenced after the ceremony and everyone who participated ate.

Today, the marriage ceremony may follow that of the old tradition or incorporate newer elements, but is still used by many Mohawk Nation marrying couples. Some couples choose to marry in the European manner and the Longhouse manner, with the Longhouse ceremony usually held first.[9]

Longhouses

Replicas of seventeenth-century longhouses have been built at landmarks and tourist villages, such as Kanata Village, Brantford, Ontario, and Awkwasasne's "Tsiionhiakwatha" interpretation village. Other Mohawk Nation Longhouses are found on the Mohawk territory reserves that hold the Mohawk law recitations, ceremonial rites, and the Mohawk and Longhouse religion (or 'Code of Handsome Lake'). These include:

- Ohswé:ken(Six Nations) First Nation Territory, Ontario holds six Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Wáhta First Nation Territory, Ontario holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kenhtè:ke(Tyendinaga) First Nation Territory, Ontario holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Ahkwesásne First Nation Territory, Quebec holds two Mohawk Ceremonial Community Longhouses.

- Ka'nehsatà:ke First Nation Territory, Quebec holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouses.

- Kahnawà:ke First Nation Territory, Quebec holds three Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kanièn:ke(Ganienkeh) First Nation Territory, New York State holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kana'tsioharà:ke First Nation Territory, New York State holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

Notable Mohawk

- Joseph Brant, Mohawk leader, British officer

- Molly Brant, Mohawk leader, sister of Joseph Brant

- Joseph Tehawehron David, Mohawk artist

- John Deseronto, Mohawk chief

- Flemish Bastard, Mohawk chief

- Hiawatha, Mohawk chief

- Kahn-Tineta Horn, activist

- Kaniehtiio Horn, film and television actress

- Waneek Horn-Miller, Olympian

- Sid Jamieson, lacrosse player, coach

- Pauline Johnson, writer

- Stan Jonathan, former NHL hockey player

- Derek Miller, singer-songwriter

- Patricia Monture-Angus, lawyer, activist, educator, and author.

- Shelley Niro (b. 1954), filmmaker, photographer, and installation artist

- Ots-Toch, wife of Dutch colonist Cornelius A. Van Slyck

- Alex Rice, actress

- Robbie Robertson, singer-songwriter, The Band

- August Schellenberg, actor

- Jay Silverheels, actor

- Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, "Lily of the Mohawks", a Catholic saint

- Billy Two Rivers, professional wrestler

See also

- African Americans with Native Heritage

- Iroquois Confederacy

- Mohawk language

- Native American tribe

- Native Americans in the United States

- Oka Crisis

- One-Drop Rule

- The Kahnawake Iroquois and the Rebellions of 1837-38

- The Flying Head

- Kahnawake surnames

Notes

- ^ Joseph Mitchell, "The Mohawks in High Steel," in Edmund Wilson, Apologies to the Iroquois (New York: Vintage, 1960), pp. 3-36."

- ^ Owen, Don. "High Steel" (Requires Adobe Flash). Online documentary. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Tarbell, Reaghan (2008). 2 "Little Caughnawaga: To Brooklyn and Back". National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Wallace, Vaughn (2012-09-11). "The Mohawk Ironworkers: Rebuilding the Iconic Skyline of New York". Time.

- ^ see C. 590 of the Laws of 2004

- ^ "The Associate Deputy Secretary of the Interior" (PDF). Washington. 4 January 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "Former Website of the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "Warren v. United States of America, et al". Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Anne Marie Shimony, "Conservatism among the Iroquois at Six Nations Reserve", 1961

References

- Snow, Dean R. (1994). The Iroquois. Boston: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 1-55786-938-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Mohawk Creation Story

- "Tsiionhiakwatha archaeological site and interpretation centre".

- "Mohawk Institute", Geronimo Henry

- Hodenasaunee Clothing and other Cultural Items

- The Wampum Chronicles: Mohawk Territory on the Internet, a website dedicated to Mohawk history, culture, and current events

- Iroquois Book of Rites

- Mohawk tribe

- Iroquois

- First Nations in Ontario

- First Nations in Quebec

- Native American history of Massachusetts

- Native American history of New York

- Native American history of Vermont

- Native American tribes in Massachusetts

- Native American tribes in New York

- Native American tribes in Vermont

- People of New Netherland

- Algonquian ethnonyms