Noise music

| Noise music | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Early 1910s Europe |

| Subgenres | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Regional scenes | |

| Japan | |

| Other topics | |

Noise music is a category of music that is characterised by the expressive use of noise within a musical context. This type of music tends to challenge the distinction that is made in conventional musical practices between musical and non-musical sound.[1] Noise music includes a wide range of musical styles and sound-based creative practices that feature noise as a primary aspect. It can feature acoustically or electronically generated noise, and both traditional and unconventional musical instruments. It may incorporate live machine sounds, non-musical vocal techniques, physically manipulated audio media, processed sound recordings, field recording, computer-generated noise, stochastic process, and other randomly produced electronic signals such as distortion, feedback, static, hiss and hum. There may also be emphasis on high volume levels and lengthy, continuous pieces. More generally noise music may contain aspects such as improvisation, extended technique, cacophony and indeterminacy, and in many instances conventional use of melody, harmony, rhythm and pulse is dispensed with.[2][3][4][5]

The Futurist art movement was important for the development of the noise aesthetic, as was the Dada art movement (a prime example being the Antisymphony concert performed on April 30, 1919 in Berlin),[6][7] and later the Surrealist and Fluxus art movements, specifically the Fluxus artists Joe Jones, Yasunao Tone, George Brecht, Robert Watts, Wolf Vostell, Dieter Roth, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Walter De Maria's Ocean Music, Milan Knížák's Broken Music Composition, early LaMonte Young and Takehisa Kosugi.[8]

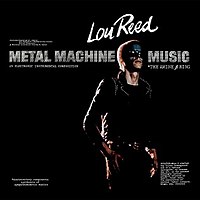

Contemporary noise music is often associated with extreme volume and distortion.[9] In the domain of experimental rock, examples include Jimi Hendrix's use of feedback,[10] Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music, and Sonic Youth.[11] Other examples of music that contain noise-based features include works by Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Helmut Lachenmann, Cornelius Cardew, Theatre of Eternal Music, Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham, Ryoji Ikeda, Survival Research Laboratories, Whitehouse, Ramleh, Coil, Brighter Death Now, Merzbow, Cabaret Voltaire, Psychic TV, Blackhouse, Jean Tinguely's recordings of his sound sculpture (specifically Bascule VII), the music of Hermann Nitsch's Orgien Mysterien Theater, and La Monte Young's bowed gong works from the late 1960s.[12] Genres such as industrial, industrial techno, lo-fi music, black metal, sludge metal, and glitch music employ noise-based materials.[13][14]

Development

The Art of Noises

Luigi Russolo, an Italian Futurist artist of the very early 20th century, was perhaps the first noise artist.[15][16] His 1913 manifesto, L'Arte dei Rumori, translated as The Art of Noises, stated that the industrial revolution had given modern men a greater capacity to appreciate more complex sounds. Russolo found traditional melodic music confining and envisioned noise music as its future replacement. He designed and constructed a number of noise-generating devices called intonarumori and assembled a noise orchestra to perform with them. Works entitled Risveglio di una città (Awakening of a City) and Convegno d'aeroplani e d'automobili (The Meeting of Aeroplanes and Automobiles) were both performed for the first time in 1914.[17]

A performance of his Gran Concerto Futuristico (1917) was met with strong disapproval and violence from the audience, as Russolo himself had predicted. None of his intoning devices have survived, though recently some have been reconstructed and used in performances. Although Russolo's works bear little resemblance to contemporary noise music such as Japanoise, his efforts helped to introduce noise as a musical aesthetic and broaden the perception of sound as an artistic medium.[18][19]

At first the art of music sought purity, limpidity and sweetness of sound. Then different sounds were amalgamated, care being taken, however, to caress the ear with gentle harmonies. Today music, as it becomes continually more complicated, strives to amalgamate the most dissonant, strange and harsh sounds. In this way we come ever closer to noise-sound.

— Luigi Russolo The Art of Noises (1913)[20]

Antonio Russolo, Luigi's brother and fellow Italian Futurist composer, produced a recording of two works featuring the original intonarumori. The 1921 made phonograph with works entitled Corale and Serenata, combined conventional orchestral music set against the famous noise machines and is the only surviving sound recording.[21]

An early Dada-related work from 1916 by Marcel Duchamp also worked with noise, but in an almost silent way. One of the found object Readymades of Marcel Duchamp, A Bruit Secret (With Hidden Noise), was a collaborative work that created a noise instrument that Duchamp accomplished with Walter Arensberg.[22] What rattles inside when A Bruit Secret is shaken remains a mystery.[23]

Found sound

In the same period the utilisation of found sound as a musical resource was starting to be explored. An early example is Parade, a performance produced at the Chatelet Theatre, Paris, on May 18, 1917, that was conceived by Jean Cocteau, with design by Pablo Picasso, choreography by Leonid Massine, and music by Eric Satie. The extra-musical materials used in the production were referred to as trompe l'oreille sounds by Cocteau and included a dynamo, Morse code machine, sirens, steam engine, airplane motor, and typewriters.[24] Arseny Avraamov's composition Symphony of Factory Sirens involved navy ship sirens and whistles, bus and car horns, factory sirens, cannons, foghorns, artillery guns, machine guns, hydro-airplanes, a specially designed steam-whistle machine creating noisy renderings of Internationale and Marseillaise for a piece conducted by a team using flags and pistols when performed in the city of Baku in 1922.[25] In 1923, Arthur Honegger created Pacific 231, a modernist musical composition that imitates the sound of a steam locomotive.[26] Another example is Ottorino Respighi's 1924 orchestral piece Pines of Rome, which included the phonographic playback of a nightingale recording.[24] Also in 1924, George Antheil created a work titled Ballet Mécanique with instrumentation that included 16 pianos, 3 airplane propellers, and 7 electric bells. The work was originally conceived as music for the Dada film of the same name, by Dudley Murphy and Fernand Léger, but in 1926 it premiered independently as a concert piece.[27][28]

In 1930 Paul Hindemith and Ernst Toch recycled records to create sound montages and in 1936 Edgard Varèse experimented with records, playing them backwards, and at varying speeds.[29] Varese had earlier used sirens to create what he called a "continuous flowing curve" of sound that he could not achieve with acoustic instruments. In 1931, Varese's Ionisation for 13 players featured 2 sirens, a lion's roar, and used 37 percussion instruments to create a repertoire of unpitched sounds making it the first musical work to be organized solely on the basis of noise.[30][31] In remarking on Varese's contributions the American composer John Cage stated that Varese had "established the present nature of music" and that he had "moved into the field of sound itself while others were still discriminating 'musical tones' from noises".[32]

In an essay written in 1937, Cage expressed an interest in using extra-musical materials[33] and came to distinguish between found sounds, which he called noise, and musical sounds, examples of which included: rain, static between radio channels, and "a truck at fifty miles per hour". Essentially, Cage made no distinction, in his view all sounds have the potential to be used creatively. His aim was to capture and control elements of the sonic environment and employ a method of sound organisation, a term borrowed from Varese, to bring meaning to the sound materials.[34] Cage began in 1939 to create a series of works that explored his stated aims, the first being Imaginary Landscape #1 for instruments including two variable speed turntables with frequency recordings.[35]

In 1961, James Tenney composed Analogue #1: Noise Study (for tape) using computer synthesized noise and Collage No.1 (Blue Suede) (for tape) by sampling and manipulating a famous Elvis Presley recording.[36]

Experimental music

I believe that the use of noise to make music will continue and increase until we reach a music produced through the aid of electrical instruments which will make available for musical purposes any and all sounds that can be heard.

— John Cage The Future of Music: Credo (1937)

In 1932, Bauhaus artists László Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Fischinger and Paul Arma experimented with modifying the physical contents of record grooves.[36]

Under the influence of Henry Cowell in San Francisco in the late 1940s,[37] Lou Harrison and John Cage began composing music for junk (waste) percussion ensembles, scouring junkyards and Chinatown antique shops for appropriately tuned brake drums, flower pots, gongs, and more.

In Europe, during the late 1940s, Pierre Schaeffer coined the term musique concrète to refer to the peculiar nature of sounds on tape, separated from the source that generated them initially.[38] Pierre Schaeffer helped form Studio d'Essai de la Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française in France during World War II. Initially serving the French Resistance, Studio d'Essai became a hub for musical development centered around implementing electronic devices in compositions. It was from this group that musique concrète was developed. A type of electroacoustic music, musique concrète is characterized by its use of recorded sound, electronics, tape, animate and inanimate sound sources, and various manipulation techniques. The first of Schaeffer's Cinq études de bruits, or Five Noise Etudes, consisted of transformed locomotive sounds.[39] The last étude, Étude pathétique, makes use of sounds recorded from sauce pans and canal boats.

Following musique concrète, other modernist art music composers such as Richard Maxfield, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Gottfried Michael Koenig, Pierre Henry, Iannis Xenakis, La Monte Young, and David Tudor, composed significant electronic, vocal, and instrumental works, sometimes using found sounds.[36] In late 1947, Antonin Artaud recorded Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu (To Have Done with the Judgment of God), an audio piece full of the seemingly random cacophony of xylophonic sounds mixed with various percussive elements, mixed with the noise of alarming human cries, screams, grunts, onomatopoeia, and glossolalia.[40][41] In 1949, Nouveau Réalisme artist Yves Klein wrote The Monotone Symphony (formally The Monotone-Silence Symphony, conceived 1947–1948), a 40-minute orchestral piece that consisted of a single 20-minute sustained chord (followed by a 20-minute silence)[42] — showing how the sound of one drone could make music. Also in 1949, Pierre Boulez befriended John Cage, who was visiting Paris to do research on the music of Erik Satie. John Cage had been pushing music in even more startling directions during the war years, writing for prepared piano, junkyard percussion, and electronic gadgetry.[43]

In 1951, Cage's Imaginary Landscape #4, a work for twelve radio receivers, was premiered in New York. Performance of the composition necessitated the use of a score that contained indications for various wavelengths, durations, and dynamic levels, all of which had been determined using chance operations.[44][45] A year later in 1952, Cage applied his aleatoric methods to tape-based composition. Also in 1952, Karlheinz Stockhausen completed a modest musique concrète student piece entitled Etude. Cage's work resulted in his famous work Williams Mix, which was made up of some six hundred tape fragments arranged according to the demands of the I Ching. Cage's early radical phase reached its height that summer of 1952, when he unveiled the first art "happening" at Black Mountain College, and 4'33", the so-called controversial "silent piece". The premiere of 4'33" was performed by David Tudor. The audience saw him sit at the piano, and close the lid of the piano. Some time later, without having played any notes, he opened the lid. A while after that, again having played nothing, he closed the lid. And after a period of time, he opened the lid once more and rose from the piano. The piece had passed without a note being played, in fact without Tudor or anyone else on stage having made any deliberate sound, although he timed the lengths on a stopwatch while turning the pages of the score. Only then could the audience recognize what Cage insisted upon: that there is no such thing as silence. Noise is always happening that makes musical sound.[46] In 1957, Edgard Varèse created on tape an extended piece of electronic music using noises created by scraping, thumping and blowing titled Poème électronique.[47][48]

In 1960, John Cage completed his noise composition Cartridge Music for phono cartridges with foreign objects replacing the 'stylus' and small sounds amplified contact microphones. Also in 1960, Nam June Paik composed Fluxusobjekt for fixed tape and hand-controlled tape playback head.[36] On May 8, 1960, six young Japanese musicians, including Takehisa Kosugi and Yasunao Tone, formed the Group Ongaku with two tape recordings of noise music: Automatism and Object. These recordings made use of a mixture of traditional musical instruments along with a vacuum cleaner, a radio, an oil drum, a doll, and a set of dishes. Moreover, the speed of the tape recording was manipulated, further distorting the sounds being recorded.[49] Canada's Nihilist Spasm Band, the world's longest-running noise act, was formed in 1965 in London, Ontario and continues to perform and record to this day, having survived to work with many of the newer generation which they themselves had influenced, such as Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth and Jojo Hiroshige of Hijokaidan. In 1967, Musica Elettronica Viva, a live acoustic/electronic improvisational group formed in Rome, made a recording titled SpaceCraft[50] using contact microphones on such "non-musical" objects as panes of glass and motor oil cans that was recorded at the Akademie der Kunste in Berlin.[51] At the end of the sixties, they took part in the collective noise action called Lo Zoo initiated by the artist Michelangelo Pistoletto.

The art critic Rosalind Krauss argued that by 1968 artists such as Robert Morris, Robert Smithson, and Richard Serra had "entered a situation the logical conditions of which can no longer be described as modernist."[52] Sound art found itself in the same condition, but with an added emphasis on distribution.[53] Antiform process art became the terms used to describe this postmodern post-industrial culture and the process by which it is made.[54] Serious art music responded to this conjuncture in terms of intense noise, for example the La Monte Young Fluxus composition 89 VI 8 C. 1:42–1:52 AM Paris Encore from Poem For Chairs, Tables, Benches, Etc. Young's composition Two Sounds (1960) was composed for amplified percussion and window panes and his Poem for Tables, Chairs and Benches (1960) used the sounds of furniture scraping across the floor.

Popular music

Recorded noise in popular music can be heard as early as in the work of Spike Jones, who in the 1930s performed and released recordings that used buckets, cans, train whistles, neighing, croaking, and chirping sounds.[55] Later in rock music, the 1964 song "Walking in the Rain", performed by The Ronettes and produced by Phil Spector contained sound effects of thunder and lightning, which earned engineer Larry Levine a Grammy nomination.[56] In 1966, Pet Sounds by the American rock band The Beach Boys featured arrangements that included unconventional instruments such as bicycle bells, dog whistles, Coca-Cola cans and barking dogs, along with the more usual keyboards and guitars. The album closes with a sampled recording of passing trains.[57][58][59] Freak Out!, the debut album by The Mothers of Invention made use of avant-garde sound collage—particularly the 1966 track The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet.[citation needed] The same year, art rock group The Velvet Underground made their first recording while produced by Andy Warhol, a track entitled "Noise".[60]

"Tomorrow Never Knows" is the final track of The Beatles' 1966 studio album Revolver; credited as a Lennon–McCartney song, it was written primarily by John Lennon with major contributions to the arrangement by Paul McCartney. The track included looped tape effects. For the track, McCartney supplied a bag of 1⁄4-inch audio tape loops he had made at home after listening to Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge. By disabling the erase head of a tape recorder and then spooling a continuous loop of tape through the machine while recording, the tape would constantly overdub itself, creating a saturation effect, a technique also used in musique concrète. The tape could also be induced to go faster and slower. McCartney encouraged the other Beatles to use the same effects and create their own loops.[61] After experimentation on their own, the various Beatles supplied a total of "30 or so" tape loops to George Martin, who selected 16 for use on the song.[62] Each loop was about six seconds long.[62] The tape loops were played on BTR3 tape machines located in various studios of the Abbey Road building[63] and controlled by EMI technicians in studio two at Abbey Road.[64][65] Each machine was monitored by one technician, who had to keep a pencil within each loop to maintain tension.[62] The four Beatles controlled the faders of the mixing console while Martin varied the stereo panning and Geoff Emerick watched the meters.[66][67] Eight of the tapes were used at one time, changed halfway through the song.[66] The tapes were made (like most of the other loops) by superimposition and acceleration (0:07).[68][69] According to Martin, the finished mix of the tape loops cannot be repeated because of the complex and random way in which they were laid over the music.[70]

The Beatles would continue these efforts with "Revolution 9", a track produced in 1968 for The White Album. It made sole use of sound collage, credited to Lennon–McCartney, but created primarily by John Lennon with assistance from George Harrison and Yoko Ono. As Lennon described it, "Revolution 9" was made with the cut-up technique, cutting classical music tapes into about thirty loops (some played backwards). These loops were fed onto one master track.[71] The composition style is similar to the avant-garde Fluxus style of Ono as well as the musique concrète works of composers such as Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry. Lennon followed up this experiment with even more explicit noise music recordings, the first being Unfinished Music No.1: Two Virgins, an avant-garde recording by John Lennon and Yoko Ono from 1968 consisting of repeating tape loops as Lennon plays different instruments such as piano, organ, and drums with sound effects (including reverb, delay and distortion), changes tapes and plays other recordings, and converses with Ono, who vocalises ad-lib in response to the sounds.[72] They followed this recording with another noise recording in 1969 entitled Unfinished Music No.2: Life with the Lions. Beatles member George Harrison also released a noise/musique concrète recording in 1969, titled Electronic Sound.

In 1975, Ned Lagin released an album of electronic noise music full of spacey rumblings and atmospherics filled with burps and bleeps entitled Seastones on Round Records.[73] The album was recorded in stereo quadraphonic sound and featured guest performances by members of the Grateful Dead, including Jerry Garcia playing treated guitar and Phil Lesh playing electronic Alembic bass.[74] David Crosby, Grace Slick and other members of the Jefferson Airplane also appear on the album.[75]

Postmodern developments: Noise as genre

Noise rock and No Wave music

Lou Reed's double LP Metal Machine Music (1975) is cited as containing the primary characteristics of what would in time become a genre known as noise music.[76] The album is an early, well-known example of commercial studio noise music[77] that the music critic Lester Bangs has sarcastically called the "greatest album ever made in the history of the human eardrum".[78] It has also been cited as one of the "worst albums of all time".[79] Reed was well aware of the drone music of La Monte Young.[80][81] Young's Theatre of Eternal Music was a minimal music noise group in the mid-60s with John Cale, Marian Zazeela, Henry Flynt, Angus Maclise, Tony Conrad, and others.[82] The Theatre of Eternal Music's discordant sustained notes and loud amplification had influenced Cale's subsequent contribution to The Velvet Underground in his use of both discordance and feedback.[83] Cale and Conrad have released noise music recordings they made during the mid-sixties, such as Cale's Inside the Dream Syndicate series (The Dream Syndicate being the alternative name given by Cale and Conrad to their collective work with Young).[84] The aptly named noise rock fuses rock to noise, usually with recognizable "rock" instrumentation, but with greater use of distortion and electronic effects, varying degrees of atonality, improvisation, and white noise. One notable band of this genre is Sonic Youth who took inspiration from the No Wave composers Glenn Branca and Rhys Chatham (himself a student of LaMonte Young).[85] Marc Masters, in his book on the No Wave, points out that aggressively innovative early dark noise groups like Mars and DNA drew on punk rock, avant-garde minimalism and performance art.[86] Important in this noise trajectory are the nine nights of noise music called Noise Fest that was organized by Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth in the NYC art space White Columns in June 1981[87][88] followed by the Speed Trials noise rock series organized by Live Skull members in May 1983.

Industrial music

In the 1970s, the concept of art itself expanded and groups like Survival Research Laboratories, Borbetomagus and Elliott Sharp embraced and extended the most dissonant and least approachable aspects of these musical/spatial concepts. Around the same time, the first postmodern wave of industrial noise music appeared with Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, and NON (aka Boyd Rice).[89] These cassette culture releases often featured zany tape editing, stark percussion and repetitive loops distorted to the point where they may degrade into harsh noise.[90] In the 1970s and 1980s, industrial noise groups like Current 93, Hafler Trio, Throbbing Gristle, Coil, Laibach, Steven Stapleton, Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, Smegma, Nurse with Wound, Einstürzende Neubauten, The Haters, and The New Blockaders performed industrial noise music mixing loud metal percussion, guitars, and unconventional "instruments" (such as jackhammers and bones) in elaborate stage performances. These industrial artists experimented with varying degrees of noise production techniques.[91] Interest in the use of shortwave radio also developed at this time, particularly evident in the recordings and live performances of John Duncan. Other postmodern art movements influential to post-industrial noise art are Conceptual Art and the Neo-Dada use of techniques such as assemblage, montage, bricolage, and appropriation. Bands like Test Dept, Clock DVA, Factrix, Autopsia, Nocturnal Emissions, Whitehouse, Severed Heads, Sutcliffe Jügend, and SPK soon followed. The sudden post-industrial affordability of home cassette recording technology in the 1970s, combined with the simultaneous influence of punk rock, established the No Wave aesthetic, and instigated what is commonly referred to as noise music today.[91]

Japanese noise music

Since the early 1980s,[92] Japan has produced a significant output of characteristically harsh bands, sometimes referred to under the portmanteau Japanoise, with perhaps the best known being Merzbow (pseudonym for the Japanese noise artist Masami Akita who himself was inspired by the Dada artist Kurt Schwitters's Merz art project of psychological collage).[93][94] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Akita took Metal Machine Music as a point of departure and further abstracted the noise aesthetic by freeing the sound from guitar based feedback alone, a development that is thought to have heralded noise music as a genre.[95] According to Hegarty (2007), "in many ways it only makes sense to talk of noise music since the advent of various types of noise produced in Japanese music, and in terms of quantity this is really to do with the 1990s onwards ... with the vast growth of Japanese noise, finally, noise music becomes a genre".[96] Other key Japanese noise artists that contributed to this upsurge of activity include Hijokaidan, Boredoms, C.C.C.C., Incapacitants, KK Null, Yamazaki Maso's Masonna, Solmania, K2, The Gerogerigegege and Hanatarash.[94][97] Nick Cain of The Wire identifies the "primacy of Japanese Noise artists like Merzbow, Hijokaidan and Incapacitants" as one of the major developments in noise music since 1990.[98]

Post-digital music

Following the wake of industrial noise, noise rock, no wave, and harsh noise, there has been a flood of noise musicians whose ambient, microsound, or glitch-based work is often subtler to the ear.[99] Kim Cascone refers to this development as a postdigital movement and describes it as an "aesthetic of failure."[100] Some of this music has seen wide distribution thanks to peer-to-peer file sharing services and netlabels offering free releases. Goodman characterizes this widespread outpouring of free noise based media as a "noise virus."[101][102]

Definitions

According to Danish noise and music theorist Torben Sangild, one single definition of noise in music is not possible. Sangild instead provides three basic definitions of noise: a musical acoustics definition, a second communicative definition based on distortion or disturbance of a communicative signal, and a third definition based in subjectivity (what is noise to one person can be meaningful to another; what was considered unpleasant sound yesterday is not today).[103]

According to Murray Schafer there are four types of noise: unwanted noise, unmusical sound, any loud sound, and a disturbance in any signaling system (such as static on a telephone).[104] Definitions regarding what is considered noise, relative to music, have changed over time.[105] Ben Watson, in his article Noise as Permanent Revolution, points out that Ludwig van Beethoven's Grosse Fuge (1825) "sounded like noise" to his audience at the time. Indeed, Beethoven's publishers persuaded him to remove it from its original setting as the last movement of a string quartet. He did so, replacing it with a sparkling Allegro. They subsequently published it separately.[106]

In attempting to define noise music and its value, Paul Hegarty (2007) cites the work of noted cultural critics Jean Baudrillard, Georges Bataille and Theodor Adorno and through their work traces the history of "noise". He defines noise at different times as "intrusive, unwanted", "lacking skill, not being appropriate" and "a threatening emptiness". He traces these trends starting with 18th-century concert hall music. Hegarty contends that it is John Cage's composition 4'33", in which an audience sits through four and a half minutes of "silence" (Cage 1973), that represents the beginning of noise music proper. For Hegarty, "noise music", as with 4'33", is that music made up of incidental sounds that represent perfectly the tension between "desirable" sound (properly played musical notes) and undesirable "noise" that make up all noise music from Erik Satie to NON to Glenn Branca. Writing about Japanese noise music, Hegarty suggests that "it is not a genre, but it is also a genre that is multiple, and characterized by this very multiplicity ... Japanese noise music can come in all styles, referring to all other genres ... but crucially asks the question of genre—what does it mean to be categorized, categorizable, definable?" (Hegarty 2007:133).

Writer Douglas Kahn, in his work Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (1999), discusses the use of noise as a medium and explores the ideas of Antonin Artaud, George Brecht, William Burroughs, Sergei Eisenstein, Fluxus, Allan Kaprow, Michael McClure, Yoko Ono, Jackson Pollock, Luigi Russolo, and Dziga Vertov.

In Noise: The Political Economy of Music (1985), Jacques Attali explores the relationship between noise music and the future of society. He indicates that noise in music is a predictor of social change and demonstrates how noise acts as the subconscious of society—validating and testing new social and political realities.[107]

Characteristics

Like much of modern and contemporary art, noise music takes characteristics of the perceived negative traits of noise mentioned below and uses them in aesthetic and imaginative ways.[108]

In common use, the word noise means unwanted sound or noise pollution.[109] In electronics noise can refer to the electronic signal corresponding to acoustic noise (in an audio system) or the electronic signal corresponding to the (visual) noise commonly seen as 'snow' on a degraded television or video image.[110] In signal processing or computing it can be considered data without meaning; that is, data that is not being used to transmit a signal, but is simply produced as an unwanted by-product of other activities. Noise can block, distort, or change the meaning of a message in both human and electronic communication. White noise is a random signal (or process) with a flat power spectral density.[111] In other words, the signal contains equal power within a fixed bandwidth at any center frequency. White noise is considered analogous to white light which contains all frequencies.[112]

In much the same way the early modernists were inspired by naïve art, some contemporary digital art noise musicians are excited by the archaic audio technologies such as wire-recorders, the 8-track cartridge, and vinyl records.[113] Many artists not only build their own noise-generating devices, but even their own specialized recording equipment and custom software (for example, the C++ software used in creating the viral symphOny by Joseph Nechvatal).[114][115]

Compilations

- An Anthology of Noise & Electronic Music, Volumes 1–7 Sub Rosa, Various Artists (1920–2012)

- Bip-Hop Generation (2001–2008) Volumes 1–9, various artists, Paris

- Independent Dark Electronics Volume #1 (2008) IDE

- Japanese Independent Music (2000) various artists, Paris Sonore

- Just Another Asshole #5 (1981) compilation LP (CD reissue 1995 on Atavistic #ALP39CD), producers: Barbara Ess & Glenn Branca

- New York Noise, Vol. 1–3 (2003, 2006, 2006) Soul Jazz B00009OYSE, B000CHYHOG, B000HEZ5CC

- Noise May-Day 2003, various artists, Coquette Japan CD Catalog#: NMD-2003

- No New York (1978) Antilles, (2006) Lilith, B000B63ISE

- Women take back the Noise Compilation (2006) ubuibi

- "The Allegheny White Fish Tapes" (2009), Tobacco, Rad Cult

- The Japanese-American Noise Treaty (1995) CD, Relapse

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Priest, Eldritch. "Music Noise" in Boring Formless Nonsense: Experimental Music and The Aesthetics of Failure, p. 132. London: Bloomsbury Publishing; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

- ^ Chris Atton, "Fan Discourse and the Construction of Noise Music as a Genre", Journal of Popular Music Studies 23, no. 3 (September 2011): 324–42. Citation on 326.

- ^ Torben Sangild, The Aesthetics of Noise (Copenhagen: Datanom, 2002):[page needed]. ISBN 87-988955-0-8. Reprinted at UbuWeb.

- ^ Paul Hegarty, Noise/Music: A History (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007): 3–19.

- ^ Caleb Kelly, Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction (Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press, 2009): 60–76.

- ^ Matthew Biro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin, 2009, p. 50.

- ^ Documents at The International Dada archive at The University of Iowa show that Antisymphonie was held at the Graphisches Kabinett, Kurfürstendamm 232, at 7:45 PM. The printed program lists 5 numbers: "Proclamation dada 1919" by Huelsenbeck, "Simultan-Gedicht" performed by 7 people, "Bruitistisches Gedicht" performed by Huelsenbeck (these latter 2 pieces grouped together under the category "DADA-machine"), "Seelenautomobil" by Hausmann, and finally, Golyscheff's Antisymphonie in 3 movements, subtitled "Musikalische Kriegsguillotine". The 3 movements of Golyscheff's piece are titled "provokatorische Spritze", "chaotische Mundhöhle oder das submarine Flugzeug", and "zusammenklappbares Hyper-fis-chendur".

- ^ Owen Smith, Fluxus: The History of an Attitude (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, 1998), pp. 7 & 82.

- ^ Piekut, Benjamin. Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits. 2012. p. 193

- ^ "Jimi Hendrix". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Lou Reed and Amanda Petrusich "Interview: Lou Reed", Pitchfork Media (2007-09-17). (Archive from 23 November 2011, accessed 9 December 2013).

- ^ Such as 23 VIII 64 2:50:45 – 3:11 am The Volga Delta From Studies In The Bowed Disc from The Black Record (1969)

- ^ Paul Hegarty, Noise/Music: A History (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007), pp. 189–92.

- ^ Caleb Kelly, Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2009), pp. 6–10.

- ^ In "Futurism and Musical Notes", Daniele Lombardi discusses the mysterious case of the French composer Carol-Bérard; a pupil of Isaac Albéniz. Carol-Bérard is said to have composed a Symphony of Mechanical Forces in 1910, but little evidence has emerged thus far to establish this assertion.

- ^ Unknown.nu Luigi Russolo, "The Art of Noises".

- ^ Benjamin Thorn,"Luigi Russolo (1885–1947)", in Music of the Twentieth-Century Avant-Garde: A Biocritical Sourcebook, edited by Larry Sitsky, foreword by Jonathan Kramer, 415–19 (Westport and London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002). ISBN 0-313-29689-8. Citation on page 419.

- ^ Paul Hegarty, Noise/Music: A History (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007), pp. 13–14.

- ^ László Moholy-Nagy in 1923 recognized the unprecedented efforts of the Italian Futurists to broaden our perception of sound using noise. In an article in Der Storm #7, he outlined the fundamentals of his own experimentation: "I have suggested to change the gramophone from a reproductive instrument to a productive one, so that on a record without prior acoustic information, the acoustic information, the acoustic phenomenon itself originates by engraving the necessary Ritchriftreihen (etched grooves)." He presents detailed descriptions for manipulating discs, creating "real sound forms" to train people to be "true music receivers and creators" (Rice 1994,[page needed]).

- ^ Russolo, Luigi from The Art of Noises, March 1913.

- ^ Albright, Daniel (ed.) Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Source. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2004. p. 174

- ^ Chilvers, Ian & Glaves-Smith, John eds., Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. pp. 587–588

- ^ Michel Sanouillet & Elmer Peterson (Eds.), The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, Da Capo Press, p. 135.

- ^ a b Chadabe 1996, p. 23

- ^ Sonification.eu, Martin John Callanan (artist), Sonification of You.

- ^ Albright, Daniel (ed.) Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Source. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2004. p. 386

- ^ [1], The Ballet Mécanique.

- ^ Chadabe 1996, pp. 23–24

- ^ UbuWeb Papers A Brief history of Anti-Records and Conceptual Records by Ron Rice.

- ^ Chadabe 1996, p. 59

- ^ Nyman 1974, p. 44

- ^ Chadabe 1996, p. 58

- ^ Griffiths 1995, p. 27

- ^ Chadabe 1996, p. 26

- ^ Griffiths 1995, p. 20

- ^ a b c d Paul Doornbusch, A Chronology / History of Electronic and Computer Music and Related Events 1906–2011 [2]

- ^ Henry Cowell, "The Joys of Noise", in Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music (New York: Continuum, 2004), pp. 22–24.

- ^ D. Teruggi, "Technology and Musique Concrete: The Technical Developments of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales and Their Implication in Musical Composition", Organised Sound 12, no. 3 (2007): 213–31.

- ^ Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), p. 369.

- ^ Antonin Artaud Pour en finir avec le jugement de dieu, original recording, edited with an introduction by Marc Dachy. Compact Disc (Sub Rosa/aural documents, 1995).

- ^ Paul Hegarty, Noise/Music: A History, pp. 25–26.

- ^ An account and sound recording of The Monotone Symphony performed March 9, 1960 (Archive.org copy of 2001).

- ^ Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century(New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), p. 365.

- ^ Griffiths 1995, p. 25

- ^ John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1961), p. 59.

- ^ Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), p. 401.

- ^ "OHM- The Early Gurus of Electronic Music: Edgard Varese's "Poem Electronique"", Perfect Sound Forever website (accessed 20 October 2009).

- ^ Albright, Daniel (ed.) Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Source. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2004. p. 185.

- ^ Charles Mereweather (ed.), Art Anti-Art Non-Art (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2007), pp. 13 & 16.

- ^ Spacecraft was recorded in Cologne in 1967 by Bryant, Curran, Rzewski, Teitelbaum and Vandor

- ^ [3] Liner Notes for Musica Elettronica Viva recording set MEV 40 (1967–2007) 80675-2 (4CDs)

- ^ Rosalind E. Krauss, The Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths: Sculpture in the Expanded Field (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1986), pp. 30–44.

- ^ Joseph Nechvatal & Carlo McCormick essays in TellusTools liner notes (New York: Harvestworks ed., 2001).

- ^ Rosalind Krauss, "Sculpture in the Expanded Field", October 8 (Spring 1979), pp. 30–44.

- ^ Hayward, Philip (1999). Widening the Horizon: Exoticism in Post-war Popular Music. J. Libbey. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-86462-047-4.

- ^ Matthew Greenwald. "Walking in the Rain". AllMusic.

- ^ Cobley, Mike (September 9, 2007). "Brighton Beach Boys: 'Getting Better' All The Time!". The Brighton Magazine. Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Richie Unterberger review of Pet Sounds". AllMusic.

- ^ Laura Tunbridge, The Song Cycle (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0-521-72107-5, p.173.

- ^ [4] Warhol Live: Music and Dance in Andy Warhol's Workat the Frist Center for the Visual Arts by Robert Stalker

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 601.

- ^ a b c Martin 1994, p. 80.

- ^ Martin 1994, pp. 80–81.

- ^ McCartney 1995.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 291.

- ^ a b Martin 1994, p. 81.

- ^ MacDonald 1995.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 292.

- ^ MacDonald 1995, p. 190.

- ^ Martin 1995b.

- ^ from Rolling Stone issues # 74 & 75 (21 Jan & 4 Feb, 1971). "John Lennon: The Rolling Stone Interview" by editor Jann Wenner

- ^ Mark Kemp, "She Who Laughs Last: Yoko Ono Reconsidered", Option Magazine (July–August 1992), pp. 74–81.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Family Discography: Seastones".

- ^ "Grateful Dead Biography", Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ Seastones was re-released in stereo on CD by Rykodisc in 1991. The CD version includes the original nine-section "Sea Stones" (42:34) from February 1975, and a live, previously unreleased, six-section version (31:05) from December 1975.

- ^ Atton (2011:326)

- ^ [5] Metal Machine Music 8-Track Hall of Fame.

- ^ Lester Bangs, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung: The Work of a Legendary Critic, Greil Marcus, ed. (1988) Anchor Press, p. 200.

- ^ Charlie Gere, Art, Time and Technology: Histories of the Disappearing Body, (2005) Berg, p. 110.

- ^ Reed mentions (and misspells) Young's name on the cover of Metal Machine Music: "Drone cognizance and harmonic possibilities vis a vis Lamont Young's Dream Music".

- ^ Asphodel.com Zeitkratzer Lou ReedMetal Machine Music.

- ^ "Minimalism (music)", Encarta (Accessed 20 October 2009). Archived April 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine 2009-11-01.

- ^ Steven Watson, Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties (2003) Pantheon, New York, p. 157.

- ^ Watson, Factory Made, p. 103.

- ^ "Rhys Chatham", Kalvos-Damien website. (Accessed 20 October 2009).

- ^ Marc Masters, No Wave (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Rob Young (ed.), The Wire Primers: A Guide To Modern Music (London: Verso, 2009), p. 43.

- ^ Marc Masters, No Wave (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007), pp. 170–71.

- ^ Media.hyperreal.org, Prehistory of Industrial Music 1995 Brian Duguid, esp. chapter "Access to Information".

- ^ Rob Young (ed.), The Wire Primers: A Guide To Modern Music (London: Verso, 2009), p. 29.

- ^ a b Media.hyperreal.org, Prehistory of Industrial Music 1995 Brian Duguid, esp. chapter "Organisational Autonomy / Extra-Musical Elements".

- ^ Hegarty 2007, p. 133

- ^ Paul Hegarty, "Full With Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music", Ctheory.net.

- ^ a b Young, Rob (ed.), The Wire Primers: A Guide To Modern Music (London: Verso, 2009), p. 30.

- ^ Van Nort (2006:177)

- ^ Hegarty (2007:133)

- ^ Japanoise.net, japanoise noisicians profiled at japnoise.net.

- ^ Nick Cain, "Noise" The Wire Primers: A Guide to Modern Music, Rob Young, ed., London: Verso, 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Caleb Kelly, Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2009), pp. 6–24.

- ^ Cascone, Kim. "The Aesthetics of Failure: 'Post-Digital' Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music". Computer Music Journal 24, no. 4 (Winter 2002): pp. 12–18.

- ^ Goodman, Steve. "Contagious Noise: From Digital Glitches to Audio Viruses", in Parikka, Jussi and Sampson, Tony D. (eds.) The Spam Book: On Viruses, Porn and Other Anomalies From the Dark Side of Digital Culture. Cresskill, New Jersey: Hampton Press. 2009. pp. 128.

- ^ Goodman, Steve. "Contagious Noise: From Digital Glitches to Audio Viruses", in Parikka and Sampson (eds.) The Spam Book: On Viruses, Porn and Other Anomalies From the Dark Side of Digital Culture. Cresskill, New Jersey: Hampton Press. 2009. pp. 129–130.

- ^ Sangild, Torben, The Aesthetics of Noise. Copenhagen: Datanom, 2002. pp. 12–13

- ^ Schafer 1994:182

- ^ Joseph Nechvatal, Immersion Into Noise (Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, 2012), p. 19.

- ^ Watson 2009, 109–10.

- ^ Allen S. Weiss, Phantasmic Radio (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1995), p. 90.

- ^ Ctheory.net Paul Hegarty, "Full With Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music", in Life in the Wires, edited by Arthur Kroker and Marilouise Kroker, 86–98 (Victoria, Canada: NWP Ctheory Books, 2004).

- ^ Nonoise.org About Noise, Noise Pollution, and the Clearinghouse.

- ^ Noise generator to explore different types of noise.

- ^ white noise in wave(.wav) format.

- ^ Eugene Hecht, Optics, 4th edition (Boston: Pearson Education, 2001), p. [page needed]

- ^ UBU.com, Torben Sangild, "The Aesthetics of Noise", Datanom, 2002.

- ^ UBU.com, Steven Mygind Pedersen, Joseph Nechvatal: viral symphOny (Alfred, New York: Institute for Electronic Arts, School of Art & Design, Alfred University, 2007).

- ^ Observatori A.C. (ed.), Observatori 2008: After The Future (Valencia, Spain: Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia, 2008), p. 80.

References

- Albright, Daniel (ed.) Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Source. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Attali, Jacques. Noise: The Political Economy of Music, translated by Brian Massumi, foreword by Fredric Jameson, afterword by Susan McClary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

- Atton, Chris (2011). "Fan Discourse and the Construction of Noise Music as a Genre". Journal of Popular Music Studies, Volume 23, Issue 3, pages 324–42, September 2011.

- Bangs, Lester. Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung: The Work of a Legendary Critic, collected writings,edited by Greil Marcus. Anchor Press, 1988.

- Biro, Matthew. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

- Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Wesleyan University Press, 1961. Reprinted 1973.

- Cage, John. "The Future of Music: Credo (1937)". In John Cage, Documentary Monographs in Modern Art, edited by Richard Kostelanetz, Praeger Publishers, 1970

- Cahoone, Lawrence. From Modernism to Postmodernism: An Anthology. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell, 1996.

- Cain, Nick "Noise" in The Wire Primers: A Guide to Modern Music, Rob Young, ed., London: Verso, 2009.

- Cascone, Kim. "The Aesthetics of Failure: 'Post-Digital' Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music".Computer Music Journal 24, no. 4 (Winter 2002): 12–18.

- Chadabe, Joel (1996). Electronic Sound: The Past and Promise of Electronic Music. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 370. ISBN 0-13-303231-0.

- Cowell, Henry. The Joys of Noise in Audio Culture. Readings in Modern Music, edited by Christoph Cox and Dan Warner, pp. 22–24. New York: Continuum, 2004. ISBN 0-8264-1614-4 (hardcover) ISBN 0-8264-1615-2 (pbk)

- De Maria, Walter Ocean Music (1968)[full citation needed]

- Gere, Charles. Art, Time and Technology: Histories of the Disappearing Body. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2005.

- Griffiths, Paul (1995). Modern Music and After: Directions Since 1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 373. ISBN 0-19-816511-0.

- Goodman, Steve. 2009. "Contagious Noise: From Digital Glitches to Audio Viruses". In The Spam Book: On Viruses, Porn and Other Anomalies From the Dark Side of Digital Culture, edited by Jussi Parikka and Tony D. Sampson, 125–40.. Cresskill, New Jersey: Hampton Press.

- Hecht, Eugene. Optics, 4th edition. Boston: Pearson Education, 2001.

- Hegarty, Paul. 2004. "Full with Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music". In Life in the Wires, edited by Arthur Kroker and Marilouise Kroker, 86–98. Victoria, Canada: NWPCtheory Books.

- Hegarty, Paul. Noise/Music: A History. London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007.

- Piekut, Benjamin. Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

- Kahn, Douglas. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

- Kelly, Caleb. Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press, 2009.

- Kemp, Mark. 1992. "She Who Laughs Last: Yoko Ono Reconsidered". Option Magazine (July–August): 74–81.

- Krauss, Rosalind E.. 1979. The Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge: MIT Press. Reprinted as Sculpture in the Expanded Field. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986.

- LaBelle, Brandon. 2006. Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art. New York and London: Continuum International Publishing.

- Landy, Leigh (2007),Understanding the Art of Sound Organization, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, xiv, 303p.

- Lewisohn, Mark. 1988. The Beatles Recording Sessions. New York: Harmony Books.

- Lombardi, Daniele. 1981. "Futurism and Musical Notes". Artforum.[full citation needed]

- McCartney, Paul (1995). The Beatles Anthology (DVD). Event occurs at Special Features, Back at Abbey Road May 1995, 0:12:17.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Second Revised ed.). London: Pimlico (Rand). ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martin, George (1994). Summer of Love: The Making of Sgt Pepper. MacMillan London Ltd. ISBN 0-333-60398-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Masters, Marc. 2007. No Wave London: Black Dog Publishing.

- Mereweather, Charles (ed.). 2007. Art Anti-Art Non-Art. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Many Years From Now. Vintage – Random House. ISBN 0-7493-8658-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nechvatal, Joseph. 2012. Immersion Into Noise. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press. ISBN 978-1-60785-241-4.

- Nechvatal, Joseph. 2000. Towards a Sound Ecstatic Electronica. New York: The Thing. Post.thing.net

- Nyman, Michael (1974). Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. London: Studio Vista. p. 196. ISBN 0-19-816511-0.

- Pedersen, Steven Mygind. 2007. Notes on Joseph Nechvatal: Viral SymphOny. Alfred, New York: Institute for Electronic Arts, School of Art & Design, Alfred University.

- Petrusich, Amanda. "Interview: Lou Reed Pitchfork net. (Accessed 13 September 2009)

- Priest, Eldritch. "Music Noise". In his Boring Formless Nonsense: Experimental Music and The Aesthetics of Failure, 128–39. London: Bloomsbury Publishing; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4411-2475-3; ISBN 978-1-4411-2213-1 (pbk).

- Rice, Ron. 1994. A Brief History of Anti-Records and Conceptual Records. Unfiled: Music under New Technology 0402 [i.e., vol. 1, no. 2]: [page needed]Republished online, Ubuweb Papers (Accessed 4 December 2009).

- Ross, Alex. 2007. The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Sangild, Torben. 2002. The Aesthetics of Noise. Copenhagen: Datanom. ISBN 87-988955-0-8. Reprinted at UbuWeb

- Sanouillet, Michel, and Elmer Peterson (eds.). 1989. The Writings of Marcel Duchamp. New York: Da Capo Press.

- Smith, Owen. 1998. Fluxus: The History of an Attitude. San Diego: San Diego State University Press.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 1-84513-160-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tunbridge, Laura. 2011. The Song Cycle. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-72107-5.

- Watson, Ben. "Noise as Permanent Revolution: or, Why Culture Is a Sow Which Devours Its Own Farrow". In Noise & Capitalism, edited by Anthony and Mattin Iles, 104–20. Kritika Series. Donostia-San Sebastián: Arteleku Audiolab, 2009.

- Watson, Steven. 2003. Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties. New York: Pantheon.

- Weiss, Allen S. 1995. Phantasmic Radio. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

- Young, Rob (ed.). 2009. The Wire Primers: A Guide To Modern Music. London: Verso.

- Van Nort, Doug. (2006), Noise/music and representation systems, Organised Sound, 11(2), Cambridge University Press, pp 173–178.

Further reading

- Álvarez-Fernández, Miguel. "Dissonance, Sex and Noise: (Re)Building (Hi)Stories of Electroacoustic Music". In ICMC 2005: Free Sound Conference Proceedings. Barcelona: International Computer Music Conference; International Computer Music Association; SuviSoft Oy Ltd., 2005.

- Thomas Bey William Bailey, Unofficial Release: Self-Released And Handmade Audio In Post-Industrial Society, Belsona Books Ltd., 2012

- Barthes, Roland. "Listening". In his The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation, translated from the French by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1985. ISBN 0-8090-8075-3 Reprinted Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. ISBN 0-520-07238-3 (pbk.)

- Brassier, Ray. "Genre is Obsolete". Multitudes, no. 28 (Spring 2007) Multitudes.samizdat.net.

- Cobussen, Marcel. "Noise and Ethics: On Evan Parker and Alain Badiou". Culture, Theory & Critique, 46(1) pp. 29–42. 2005.

- Collins, Nicolas (ed.) "Leonardo Music Journal" Vol 13: "Groove, Pit and Wave: Recording, Transmission and Music" 2003.

- Court, Paula. New York Noise: Art and Music from the New York Underground 1978–88. London: Soul Jazz Publishing, in association with Soul Jazz Records, 2007. ISBN 0-9554817-0-8

- DeLone, Leon (ed.), Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

- Demers, Joanna. Listening Through The Noise. New York: Oxford University Press. 2010.

- Dempsey, Amy. Art in the Modern Era: A Guide to Schools and Movements. New York: Harry A. Abrams, 2002.

- Doss, Erika. Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002

- Foege, Alec. Confusion Is Next: The Sonic Youth Story. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994.

- Gere, Charlie. Digital Culture, second edition. London: Reaktion, 2000. ISBN 1-86189-388-4

- Goldberg, RoseLee. Performance: Live Art Since 1960. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

- Goodman, Steve a.k.a. kode9. Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear. Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press, 2010.

- Hainge, Greg (ed.). Culture, Theory and Critique 46, no. 1 (Issue on Noise, 2005)

- Harrison, Charles, and Paul Wood. Art in Theory, 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992.

- Harrison, Thomas J. 1910: The Emancipation of Dissonance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- Hegarty, Paul The Art of Noise. Talk given to Visual Arts Society at University College Cork, 2005.

- Hegarty, Paul. Noise/Music: A History. New York, London: Continuum, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8264-1726-8 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-8264-1727-5 (pbk).

- Hensley, Chad. "The Beauty of Noise: An Interview with Masami Akita of Merzbow". In Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, edited by C. Cox and Dan Warner, pp. 59–61. New York: Continuum, 2004.

- Helmholtz, Hermann von. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music, 2nd English edition, translated by Alexander J. Ellis. New York: Longmans & Co. 1885. Reprinted New York: Dover Publications, 1954.

- Hinant, Guy-Marc. "TOHU BOHU: Considerations on the nature of noise, in 78 fragments". In Leonardo Music Journal Vol 13: Groove, Pit and Wave: Recording, Transmission and Music. 2003. pp. 43–47

- Huyssen, Andreas. Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia. New York: Routledge, 1995.

- Iles, Anthony & Mattin (eds) Noise & Capitalism. Donostia-San Sebastián: Arteleku Audiolab (Kritika series). 2009.

- Juno, Andrea, and Vivian Vale (eds.). Industrial Culture Handbook. RE/Search 6/7. San Francisco: RE/Search Publications, 1983. ISBN 0-940642-07-7

- Kahn, Douglas, and Gregory Whitehead (eds.). Wireless Imagination: Sound, Radio and the Avant-Garde. Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press, 1992.

- Kocur, Zoya, and Simon Leung. Theory in Contemporary Art Since 1985. Boston: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

- LaBelle, Brandon. Noise Aesthetics in Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art, New York and London: Continuum International Publishing, pp 222–225. 2006.

- Lander, Dan. Sound by Artists. Toronto: Art Metropole, 1990.

- Licht, Alan. Sound Art: Beyond Music, between Categories. New York: Rizzoli, 2007.

- Lombardi, Daniele. Futurism and Musical Notes, translated by Meg Shore. ArtforumDanielelombardi.it

- Malpas, Simon. The Postmodern. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- McGowan, John P. Postmodernism and Its Critics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Miller, Paul D. [a.k.a. DJ Spooky] (ed.). Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture. Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press, 2008.

- Morgan, Robert P. "A New Musical Reality: Futurism, Modernism, and 'The Art of Noises'", Modernism/Modernity 1, no. 3 (September 1994): 129–51. Reprinted at UbuWeb.

- Moore, Thurston. Mix Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture. Seattle: Universe, 2004.

- Nechvatal, Joseph. Immersion Into Noise. Open Humanities Press in conjunction with the University of Michigan Library's Scholarly Publishing Office. Ann Arbor. 2011.

- David Novak, Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation, Duke University Press. 2013

- Nyman, Michael. Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond, 2nd edition. Music in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.ISBN 0-521-65297-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-521-65383-5 (pbk)

- Pratella, Francesco Balilla. "Manifesto of Futurist Musicians" from Apollonio, Umbro, ed. Documents of 20th-century Art: Futurist Manifestos. Brain, Robert, R.W. Flint, J.C. Higgitt, and Caroline Tisdall, trans. New York: Viking Press, pp. 31–38. 1973.

- Popper, Frank. From Technological to Virtual Art. Cambridge: MIT Press/Leonardo Books, 2007.

- Popper, Frank. Art of the Electronic Age. New York: Harry N. Abrams; London: Thames & Hudson, 1993. ISBN 0-8109-1928-1 (New York); ISBN 0-8109-1930-3 (New York); ISBN 0-500-23650-X (London); Paperback reprint, New York: Thames & Hudson, 1997. ISBN 0-500-27918-7.

- Ruhrberg, Karl, Manfred Schneckenburger, Christiane Fricke, and Ingo F. Walther. Art of the 20th Century. Cologne and London: Taschen, 2000. ISBN 3-8228-5907-9

- Russolo, Luigi. The Art of Noises. New York: Pendragon, 1986.

- Samson, Jim. Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality, 1900–1920. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1977.

- Schaeffer, Pierre. "Solfege de l'objet sonore". Le Solfège de l'Objet Sonore (Music Theory of the Sound Object), a sound recording that accompanied Traité des Objets Musicaux (Treatise on Musical Objects) by Pierre Schaeffer, was issued by ORTF (French Broadcasting Authority) as a long-playing record in 1967.

- Schafer, R. Murray. The Soundscape Rochester, Vt: Destiny Books, 1993. ISBN 978-0-89281-455-8

- Sheppard, Richard. Modernism-Dada-Postmodernism. Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2000.

- Steiner, Wendy. Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in 20th-Century Art. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

- Stuart, Caleb. "Damaged Sound: Glitching and Skipping Compact Discs in the Audio of Yasunao Tone, Nicolas Collins and Oval" In Leonardo Music Journal Vol 13: Groove, Pit and Wave: Recording, Transmission and Music. 2003. pp. 47–52

- Tenney, James. A History of "Consonance" and "Dissonance". White Plains, New York: Excelsior; New York: Gordon and Breach, 1988.

- Thompson, Emily. The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900–1933. Cambridge, Ma.: MIT Press, 2002.

- Voegelin, Salome. Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. London: Continuum. 2010. Chapter 2 Noise, pp. 41–76.

- Woods, Michael. Art of the Western World. Mandaluyong City: Summit Books, 1989.

- Woodward, Brett (ed.). Merzbook: The Pleasuredome of Noise. Melbourne and Cologne: Extreme, 1999.

- Young, Rob (ed.) Undercurrents: The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music. London: Continuum Books. 2002.

External links

- Nor Noise 119 mins 2004 documentary film by Tom Hovinbole at UbuWeb.

- Noise A short noise music documentary film by N.O. Smith

- Freshwidow.com, Marcel Duchamp playing and discussing his noise ready-made With Hidden Noise

- Paul Hegarty, Full With Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music on Ctheory.net

- The Future of Music: Credo, John Cage (1937) from Silence, John Cage, Wesleyan University Press

- Alphamanbeast's noise directory Information base with links to noise artists and labels

- White noise in wave(.wav) format (1 minute)

- UBU.armob.ca La Monte Young's 89 VI 8 c. 1:42–1:52 AM Paris Encore (10:33) on Tellus Audio Cassette Magazinearchive hosted at UbuWeb

- Noise generator to explore different types of noise

- PNF-library.org, Free Noise Manifesto

- Torben Sangild: "The Aesthetics of Noise"

- UBU.com, mp3 audio files of the noise music of Luigi Russolo on UbuWeb

- Noiseweb

- List of noise bands in the Noise Wiki created by noise artists for noise artists

- #13 Power Electronics at Tellus Audio Cassette Magazine housed at UbuWeb

- MP3 files by harsh noise artists

- UBU.com, Wolf Vostell's De/Collage LP Fluxus Multhipla, Italy (1980) at UbuWeb

- UBU.wfmu.org, noise music of Antonio Russolo from Tellus Audio Cassette Magazine

- Noise.as, Noise: NZ/Japan

- UBU.artmob.ca Walter De Maria Ocean Music (1968)

- Torben Sangild: "The Aesthetics of Noise"

- Weirdmusic.net WeirdMusic.net, an e-zine dedicated to weird experimental music

- Japanoise.net

- Dotdotmusic.com, Paul Hegarty, General Ecology of Sound: Japanese Noise Music as Low Form (2005)

- UBU.artmob.ca, audio excerpt from The Monotone Symphony by Yves Klein

- UBU.com, Genesis P-Orridge on the origins of Throbbing Gristle: interview by Tony Oursler on UbuWeb

- UBU.com, Group Ongaku (1960–61) at Ubuweb Recorded in 1960 & 1961 at Sogetsu Art Center, Tokyo

- RWM.macba.cat, mp3 radio lecture on Fluxus noise music

- Continuo.wordpress.com, Sound recordings from Nicolas Schöffer's spatiodynamic sculptures sourced from the DVD of an exhibition at Espace Gantner, France, 2004, titled Précurseur de l'art cybernétique.

- Marc Weidenbaum, "Classic Tellus Noise MP3s (Controlled Bleeding, Merzbow, etc.)", Classic Tellus Audio Cassette Magazine Noise

- Nam June Paik in UbuWeb Sound