Nuclear pore: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 74.132.112.89 (talk) to last version by Gökhan |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

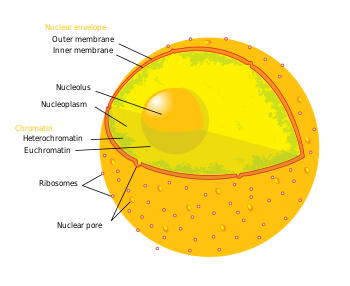

[[Image:NuclearPore crop.svg.png|right|thumb|350px|Nuclear pore. Side view. 1. Nuclear envelope. 2. Outer ring. 3. Spokes. 4. Basket. 5. Filaments. (Drawing is based on electron microscopy images)]] |

[[Image:NuclearPore crop.svg.png|right|thumb|350px|Nuclear pore. Side view. 1. Nuclear envelope. 2. Outer ring. 3. Spokes. 4. Basket. 5. Filaments. (Drawing is based on electron microscopy images)]] |

||

'''Nuclear pores''' are large [[protein]] complexes that cross the [[nuclear envelope]], which is the double [[Endomembrane system|membrane]] surrounding the [[eukaryote|eukaryotic]] [[cell (biology)|cell]] [[cell nucleus|nucleus]]. There are about on average 2000 nuclear pore complexes in the [[nuclear envelope]] of a vertebrate cell, but it varies depending on cell type and throughout the life cycle. The proteins that make up the nuclear pore complex are known as nucleoporins. About half of the nucleoporins typically contain either an [[alpha solenoid]] or a [[beta-propeller]] fold, or in some cases both as separate [[structural domain]]s. The other half show structural characteristics typical of "natively unfolded" proteins, i.e. they are highly flexible proteins that lack ordered secondary structure.<ref name=Denning_2003>{{cite journal |author=Denning D, Patel S, Uversky V, Fink A, Rexach M |title=Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: the FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A |volume=100 |issue=5 |pages=2450–5 |year=2003 |doi= 10.1073/pnas.0437902100 |pmid=12604785}}</ref> These disordered proteins are the ''FG'' nucleoporins, so called because their amino-acid sequence contains many repeats of the peptide [[phenylalanine]]—[[glycine]].<ref name=Peters_2006>{{cite journal |author=Peters R |title=Introduction to nucleocytoplasmic transport: molecules and mechanisms |journal=Methods Mol Biol |volume=322 |issue= |pages=235–58 |year=2006 |pmid=16739728| url=http://journals.humanapress.com/index.php?option=com_opbookdetails&task=chapterdetails&category=humanajournals&chapter_code=1-59745-000-6:235}}</ref> |

'''Nuclear pores''' are large [[protein]] complexes that cross the [[nuclear envelope]], which is the double [[Endomembrane system|membrane]] surrounding the [[eukaryote|eukaryotic]] [[cell (biology)|cell]] [[cell nucleus|nucleus]]. There are about on average 2000 nuclear pore complexes in the [[nuclear envelope]] of a vertebrate cell, but it varies depending on cell type and throughout the life cycle. The proteins that make up the nuclear pore complex are known as nucleoporins. About half of the nucleoporins typically contain either an [[alpha solenoid]] or a [[beta-propeller]] fold, or in some cases both as separate [[structural domain]]s. The other half show structural characteristics typical of "natively unfolded" proteins, i.e. they are highly flexible proteins that lack ordered secondary structure. ''' |

||

== Bold text == |

|||

''' |

|||

== Bold text == |

|||

'''i love jesses balls in me!!!!!!!''''''''' <ref name=Denning_2003>{{cite journal |author=Denning D, Patel S, Uversky V, Fink A, Rexach M |title=Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: the FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A |volume=100 |issue=5 |pages=2450–5 |year=2003 |doi= 10.1073/pnas.0437902100 |pmid=12604785}}</ref> These disordered proteins are the ''FG'' nucleoporins, so called because their amino-acid sequence contains many repeats of the peptide [[phenylalanine]]—[[glycine]].<ref name=Peters_2006>{{cite journal |author=Peters R |title=Introduction to nucleocytoplasmic transport: molecules and mechanisms |journal=Methods Mol Biol |volume=322 |issue= |pages=235–58 |year=2006 |pmid=16739728| url=http://journals.humanapress.com/index.php?option=com_opbookdetails&task=chapterdetails&category=humanajournals&chapter_code=1-59745-000-6:235}}</ref> |

|||

Nuclear pores allow the transport of water-soluble molecules across the nuclear envelope. This transport includes [[RNA]] and [[ribosomes]] moving from nucleus to the cytoplasm and [[protein]]s (such as [[DNA polymerase]] and [[lamin]]s), [[carbohydrates]], [[Signaling molecule|signal molecules]] and [[lipids]] moving into the nucleus. It is notable that the ''nuclear pore complex'' (NPC) can actively conduct 1000 translocations per complex per second. Although smaller molecules simply [[diffusion|diffuse]] through the pores, larger molecules may be recognized by specific signal sequences and then be diffused with the help of [[nucleoporins]] into or out of the nucleus. This is known as the [[Ran (biology)|RAN cycle]]. Each of the eight protein subunits surrounding the actual pore (the outer ring) projects a spoke-shaped protein into the pore channel. The center of the pore often appears to contains a plug-like structure. It is yet unknown whether this corresponds to an actual plug or is merely cargo caught in transit. |

Nuclear pores allow the transport of water-soluble molecules across the nuclear envelope. This transport includes [[RNA]] and [[ribosomes]] moving from nucleus to the cytoplasm and [[protein]]s (such as [[DNA polymerase]] and [[lamin]]s), [[carbohydrates]], [[Signaling molecule|signal molecules]] and [[lipids]] moving into the nucleus. It is notable that the ''nuclear pore complex'' (NPC) can actively conduct 1000 translocations per complex per second. Although smaller molecules simply [[diffusion|diffuse]] through the pores, larger molecules may be recognized by specific signal sequences and then be diffused with the help of [[nucleoporins]] into or out of the nucleus. This is known as the [[Ran (biology)|RAN cycle]]. Each of the eight protein subunits surrounding the actual pore (the outer ring) projects a spoke-shaped protein into the pore channel. The center of the pore often appears to contains a plug-like structure. It is yet unknown whether this corresponds to an actual plug or is merely cargo caught in transit. |

||

Revision as of 15:32, 21 October 2008

Nuclear pores are large protein complexes that cross the nuclear envelope, which is the double membrane surrounding the eukaryotic cell nucleus. There are about on average 2000 nuclear pore complexes in the nuclear envelope of a vertebrate cell, but it varies depending on cell type and throughout the life cycle. The proteins that make up the nuclear pore complex are known as nucleoporins. About half of the nucleoporins typically contain either an alpha solenoid or a beta-propeller fold, or in some cases both as separate structural domains. The other half show structural characteristics typical of "natively unfolded" proteins, i.e. they are highly flexible proteins that lack ordered secondary structure.

Bold text

Bold text

i love jesses balls in me!!!!!!!'''' [1] These disordered proteins are the FG nucleoporins, so called because their amino-acid sequence contains many repeats of the peptide phenylalanine—glycine.[2]

Nuclear pores allow the transport of water-soluble molecules across the nuclear envelope. This transport includes RNA and ribosomes moving from nucleus to the cytoplasm and proteins (such as DNA polymerase and lamins), carbohydrates, signal molecules and lipids moving into the nucleus. It is notable that the nuclear pore complex (NPC) can actively conduct 1000 translocations per complex per second. Although smaller molecules simply diffuse through the pores, larger molecules may be recognized by specific signal sequences and then be diffused with the help of nucleoporins into or out of the nucleus. This is known as the RAN cycle. Each of the eight protein subunits surrounding the actual pore (the outer ring) projects a spoke-shaped protein into the pore channel. The center of the pore often appears to contains a plug-like structure. It is yet unknown whether this corresponds to an actual plug or is merely cargo caught in transit.

Size and complexity

(Not True)The entire nuclear pore complex (NPC) has a diameter of about 120 nm, the diameter of the opening (functional diameter) is about 10 nm wide and its "depth" is about 200 nm.[citation needed] It had been suggested that the pore can be dilated to around 26 nm to allow molecule passage. The molecular mass of the mammilian NPC is about 120 mega dalton and it contains approximately 30 different protein components, each in multiple copies[3].

Transport through the nuclear pore complex

Small particles (< 30 kDa) are able to pass through the nuclear pore complex by passive diffusion. Larger particles are also able to pass through the large diameter of the pore but at almost negligible rates.[4] Efficient passage through the complex requires several protein factors.[5] Karyopherins, which may act as importins or exportins are part of the Importin-β super-family which all share a similar three-dimensional structure.

Three models have been suggested to explain the translocation mechanism:

- Affinity gradients along the central plug

- Brownian affinity gating

- Selective phase

Import of proteins

Any cargo with a nuclear localization signal (NLS) exposed will be destined for quick and efficient transport through the pore. Several NLS sequences are known, generally containing a conserved polypeptide sequence with basic residues such as PKKKRKV. Any material with an NLS will be taken up by importins to the nucleus.

The classical scheme of NLS-protein importation begins with Importin-α first binding to the NLS sequence, and acts as a bridge for Importin-β to attach. The importinβ—importinα—cargo complex is then directed towards the nuclear pore and diffuses through it. Once the complex is in the nucleus, RanGTP binds to Importin-β and displaces it from the complex. Then the cellular apoptosis susceptibility protein (CAS), an exportin which in the nucleus is bound to RanGTP, displaces Importin-α from the cargo. The NLS-protein is thus free in the nucleoplasm. The Importinβ-RanGTP and Importinα-CAS-RanGTP complex diffuses back to the cytoplasm where GTPs are hydrolyzed to GDP leading to the release of Importinβ and Importinα which become available for a new NLS-protein import round.

Although cargo passes through the pore with the assistance of chaperone proteins, the translocation through the pore itself is not energy dependent. However, the whole import cycle needs the hydrolysis of 2 GTPs and is thus energy dependent and has to be considered as active transport. The import cycle is powered by the nucleo-cytoplasmic RanGTP gradient. This gradient arises from the exclusive nuclear localization of RanGEFs, proteins that exchange GDP to GTP on Ran molecules. Thus there is an elevated RanGTP concentration in the nucleus compared to the cytoplasm.

Export of proteins

Some nuclear proteins need to be exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, as do ribosome subunits and messenger RNAs. Thus there is an export mechanism similar to the import mechanism.

In the classical export scheme, proteins with an nuclear export sequence (NES) can bind in the nucleus to form a heterotrimeric complex with an exportin and RanGTP (for example the exportin CRM1). The complex can then diffuse to the cytoplasm where GTP is hydrolysed and the NES-protein is released. CRM1-RanGDP diffuses back to the nucleus where GDP is exchanged to GTP by RanGEFs. This process is also energy dependent as it consumes one GTP. Export with the exportin CRM1 can be inhibited by Leptomycin B.

Export of RNA

Different export pathways from NPC for each RNA class exist. RNA export is also signal mediated (NES), the NES is in RNA-binding proteins (except for tRNA which has no adapter). It is notable that all viral RNAs and cellular RNAs (tRNA, rRNA, U snRNA, microRNA) except mRNA are dependent on RanGTP. Conseved mRNA export factors are necessary for mRNA nuclear export. Export factors are Mex67/Tap (large subunit) and Mtr2/p15 (small subunit). An adapter binds to the large export factor subunit mediating the export process.

Assembly of The NPC

As the NPC controls access to the genome, it is essential that it exists in large amounts in areas of the cell cycle where plenty of transcription is necessary. For example cycling mammalian and yeast cells double the amount of NPC in the nucleus between the G1 and G2 phase of cell Mitosis. And oocytes accumulate large numbers of NPCs to prepare for the rapid mitosis that exists in the early stages of development. Interphase cells must also keep up a level of NPC generation to keep the levels of NPC in the cell constant as some may get damaged. Some cells can even increase the NPC numbers due to increased transcriptional demand.[6] So how are these vast proteins complexes assembled? As the immunodepletion of certain protein complexes, such as the Nup 107–160 complex, leads to the formation of poreless nuclei, it seems likely that the Nup complexes are involved in fusing the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope with the inner and not that the fusing of the membrane begins the formation of the pore. There are several ways that this could lead to the formation of the full NPC.

One possibility is that as a protein complex it binds to the chromatin. It is then inserted into the double membrane close to the chromatin. This, in turn, leads to the fusing of that membrane. Around this protein complex others eventually bind forming the NPC. This method is possible during every phases of mitosis as the double membrane is present around the chromatin before the membrane fusion proteins complex can insert. Post mitotic cells could form a membrane first with pores being inserted into after formation. Another model for the formation of the NPC is the production of a prepore as a start as opposed to a single protein complex. This prepore would form when several Nup complexes come together and bind to the chromatin. This would have the double membrane form around it in during mitotic reassembly. Possible prepore structures have been observed on chromatin before nuclear envelope(NE) formation using electron microscopy[24][7] During the interphase of the cell cycle the formation of the prepore would happen within the nucleus, each component being transported in through existing NPCs. These Nups would bind to an importin, once formed, preventing the assembly of a prepore in the cytoplasm. Once transported into the nucleus Ran GTP would bind to the importin and cause it to release the cargo. This Nup would be free to from a prepore. The binding of importins has at least been shown to bring Nup 107 and the Nup 153 nucleoporins into the nucleus.[8] NPC assembly is a very rapid process yet defined intermediate states occur which leads to the idea that this assembly occurs in a stepwise fashion.[9]

A third possible method of NPC assembly is splitting. This method seems to be tailor made for NPC formation during the interphase. It happens when more protomers are added on to an existing NPC. The eightfold symmetry of the NPC has been shown to have a degree of plasticity and will allow this. Eventually enough protomers will add and allow a new NPC to split off the original. This method of NPC assembly can only happen during the interphase of the cell cycle.

During mitosis the NPC appears to disassemble in stages. Peripheral nucleoporins such as the Nup 153 Nup 98 and Nup 214 disassociate from the NPC. The rest, which can be considered a scaffold proteins remain stable, as cylindrical ring complexes within the nuclear envelope. This disassembly of the NPC peripheral groups is largely thought to be phosphate driven, as several of these nucleoporins are phosphorylated during the stages of mitosis. However, the enzyme involved in the phosphorlyation is unknown in vivo. In metazoans (which undergo open mitosis) the NE degrades quickly after the loss of the peripheral Nups. The reason for this may be due to the change in the NPC’s architecture. This change may make the NPC more permeable to enzymes involved in the degradation of the NE such as cytoplasmic tubulin, as well as allowing the entry of key mitotic regulator proteins.

It was shown, in fungi that undergo closed mitosis (where the nucleus does not degrade), that the change of the permeability barrier of the NE was due to changes with in the NPC and is what allows the entry of mitotic regulators. In Aspergillus nidulans the NPC composition appears to be effected by the mitotic kinase NIMA, possibly by phosphorylating the nucleoporins Nup98 and Gle2/Rae1. This remodelling seems to allow the proteins complex cdc2/cyclinB enter the nucleus as well as many other protens such as soluble tubulin. The NPC scaffold remains intact through out the whole closed mitosis. This seems to preserve the integrity of the NE.

Additional images

-

The Ran-GTP cycle

References

- ^ Denning D, Patel S, Uversky V, Fink A, Rexach M (2003). "Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: the FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100 (5): 2450–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0437902100. PMID 12604785.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peters R (2006). "Introduction to nucleocytoplasmic transport: molecules and mechanisms". Methods Mol Biol. 322: 235–58. PMID 16739728.

- ^ Alber F, Dokudovskaya S, Veenhoff L, Zhang W, Kipper J, Devos D, Suprapto A, Karni-Schmidt O, Williams R, Chait B, Rout M, Sali A (2007). "Determining the architectures of macromolecular assemblies". Nature. 450 (7170): 683–94. doi:10.1038/nature06404. PMID 18046405.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rodriguez M, Dargemont C, Stutz F (2004). "Nuclear export of RNA". Biol Cell. 96 (8): 639–55. doi:10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.04.014. PMID 15519698.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reed R, Hurt E (2002). "A conserved mRNA export machinery coupled to pre-mRNA splicing". Cell. 108 (4): 523–31. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00627-X. PMID 11909523.

- ^ Rabut, G., P. Lenart, and J. Ellenberg, Dynamics of nuclear pore complex organization through the cell cycle. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2004. 16(3): p. 314-321.

- ^ Sheehan, M.A., et al., Steps in the assembly of replication-competent nuclei in a cell-free system from Xenopus eggs. J Cell Biol, 1988. 106(1): p. 1-12.

- ^ Rabut, G., P. Lenart, and J. Ellenberg, Dynamics of nuclear pore complex organization through the cell cycle. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2004. 16(3): p. 314-321.

- ^ Kiseleva, E., et al., Steps of nuclear pore complex disassembly and reassembly during mitosis in early Drosophila embryos. J Cell Sci, 2001. 114(Pt 20): p. 3607-18

External links

- Histology image: 20104loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Nuclear+pore at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Nuclear Pore Complex animations

- Nuclear Pore Complex illustrations