People's Republic of Benin

People's Republic of Benin République populaire du Bénin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1990 | |||||||||

| Anthem: The Dawn of a New Day | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Porto Novo | ||||||||

| Common languages | French | ||||||||

| Government | Marxist-Leninist one-party state | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1975–1990 | Mathieu Kérékou | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 26 October 1972 | |||||||||

• Established | 30 November 1975 | ||||||||

| 1 March 1990 | |||||||||

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | BJ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Benin |

|---|

|

| History of the Kingdom of Dahomey |

| Early history |

|

| Modern period |

|

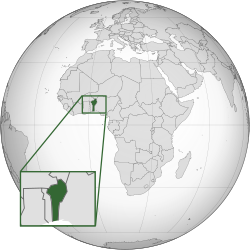

The People's Republic of Benin (French: République populaire du Bénin) was a socialist state located in the Gulf of Guinea on the African continent, which would become present-day Benin. The People's Republic was established on 30 November 1975, after the 1972 coup d'état in the Republic of Dahomey. It effectively lasted until 1 March 1990, with the adoption of a new constitution, and the abolition of Marxism-Leninism in the nation in 1989.[1][2][3]

On 26 October 1972, the army led by Commander Mathieu Kérékou overthrew the government, suspended the constitution and dissolved both the National Assembly and the Presidential Council. On 30 November 1972 it released the keynote address of New Politics of National Independence. The territorial administration was reformed, mayors and deputies replacing traditional structures (village chiefs, convents, animist priests, etc.). On 30 November 1974 he declared in the city of Abomey, before an assembly of stunned notables, a speech proclaiming the formal accession of his government to Marxism-Leninism.[4] He soon aligned Dahomey with the Soviet Union.[5] The People's Revolutionary Party of Benin, designed as a vanguard party, was created on the same day as the country's only legal party.

The first year of the Marxist government was marked by purges in the state apparatus. Kérékou condemned, and sometimes executed, various representatives of the former political regime, and some of its own employees: Captain Michel Aipké, Interior minister, was sentenced to death and executed on a charge of adultery with the wife of the head of state. He was shot, and activists invited to file past his body.[6] On 30 November 1975, with the first anniversary of the speech of Abomey, Kérékou changed the country's name to Benin, named after the Benin Empire that had once flourished in neighboring Nigeria. The National Day was set for 30 November referring to three days of 1972, 1974, and 1975, dubbed by the regime the Three Glorious.

In January 1977, an attempted coup, called Operation Shrimp,[7] led by the mercenary Bob Denard and supported by France, Gabon, and Morocco failed and it helped to harden the regime, which was officially moving toward the way of a government-political party.[8] The constitution was adopted on 26 August of that year, Article 4 stating:

"People's Republic of Benin, the road to development is socialism. Its philosophical basis is Marxism-Leninism to be applied in a lively and creative manner to the realities of Benin. All activities of national social life in the People's Republic of Benin are organized in this way under the leadership of the revolution of Benin, detachment vanguard of exploited and oppressed masses, leading core of the Beninese people as a whole and its revolution".[9]

A basic law established an all-powerful national assembly.[10]

The opposition was muzzled, and political prisoners remained in detention for years without trial. The elections were held under a system of unique applications. Campaigns were conducted for rural development and improving education. The government also pursued a policy of anti-religious inspiration, in order to root out witchcraft, forces of evil, and retrograde beliefs (West African Vodun, a traditional religion well established in the South, was prohibited,[11] which did not prevent Kérékou, a few years later, from having his personal marabout, during the period in which he identified as Muslim). Benin received only modest support from other communist countries, hosting several teams from cooperating Cuba, East Germany, the USSR, and North Korea.[12]

Benin tried to implement extensive programs of economic and social development without getting results. Mismanagement and corruption undermined the country's economy. The industrialization strategy by the internal market of Benin caused an escalation of foreign debt. Between 1980 and 1985, the annual service of its external debt raised from 20 to 49 million, while its GNP dropped from 1.402 to 1.024 billion and the stock of debt exploded from 424 to 817 million.[13] The three former presidents, Hubert Maga, Sourou Migan Apithy, and Justin Ahomadegbe (imprisoned in 1972) were released in 1981.

A new constitution was adopted in 1978, and the first elections for the National Revolutionary Assembly were held in 1979. Kérékou was elected unopposed to a four-year term as president in 1980 and reelected in 1984. As was the case in most Marxist-Leninist states, the National Revolutionary Assembly was nominally the highest source of state power, but in practice did little more than rubber-stamp decisions already made by Kérékou and the PRPB.

In 1986, the economic situation in Benin had become critical: the system, ironically, already dubbed the Marxism-Beninism,[14] inherited the nickname of laxism-Leninism. A popular running gag said that the number of supporters convinced by the regime did not exceeded twelve.[15] Agriculture was disorganized, the Commercial Bank of Benin ruined, and communities were largely paralyzed due to lack of budget. On the political front, the violations of human rights, with cases of torture of political prisoners, contributed to social tension: the church and the unions opposed more openly the regime.[16] Plans for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed in 1987 draconian economic measures: 10% additional levy on wages, hiring freezes, and compulsory retirements. On June 16, 1989, the People's Republic of Benin signed with the IMF a first adjustment plan, in exchange for enhanced structural adjustment facility (ESAF) of 21.9 million Special Drawing Rights of the IMF. Were planned: a reduction in public expenditure and tax reform, privatizations, reorganization or liquidation of public enterprises, a policy of liberalization and the obligation to enter into that borrowing at concessional rates. The IMF agreement set off a massive strike of students and staff, requiring the payment of their salaries and their scholarships. On 22 June 1989, the country signed a rescheduling agreement first with the Paris Club, for a total of $199 million and Benin was granted a 14.1% reduction of its debt.

The social and political turmoil, the catastrophic economic situation and the fall of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, lead Kérékou to agree to bring down his regime. In February 1989, a pastoral letter signed by eleven bishops of Benin expressed its condemnation of the PRC. On 7 December 1989, Kérékou took the lead and surprised the people disseminating an official statement announcing the abandonment of Marxism-Leninism, the liquidation of the Political Bureau, and the closure of the party's central committee.[17] The Government accepted the establishment of a National Conference bringing together representatives of different political movements. The Conference opened on 19 February 1990: Kérékou expressed himself in person on 21 February, publicly recognising the failure of his policy. The work of the Conference decided to draft a new constitution and the establishment of a democratic process provided by a provisional government entrusted to a prime minister. Kérékou remained head of state on a temporary basis. Kérékou said on 28 February to the attention of the Conference:

I accept all the conclusions of your work.[18]

A transitional government was set up in 1990, paving the way for the return of democracy and multi-party system. The new constitution was adopted by referendum on December 1990. The official name of Benin was preserved for the country, which became the Republic of Benin. Prime Minister Nicephore Soglo, won 67.7% of the votes and defeated Kérékou in the presidential election in March 1991. Kérékou accepted the election results and left his office. He became president again by winning the election in 1996, having meanwhile dropped all references to Marxism and to atheism to become an evangelical pastor. His return to power involved no recovery of a Marxist-Leninist regime in Benin.

References

- ^ Benin

- ^ A short history of the People's Republic of Benin (1974 - 1990)

- ^ "Constitution de la République du Bénin" (PDF) (in French). Government of Benin. 11 December 1990. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

Devenu République Populaire du Bénin le 30 Novembre 1975, puis République du Bénin le 1er mars 1990...

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Philippe David,The Benin, Karthala, 1998, page 60

- ^ Auzias Dominique, Jean-Paul Labourdette, Sandra Fontaine,Benin Smart Little Country Guide, page 34

- ^ Philippe David, The Benin, Karthala, 1998, page 61

- ^ Roger Faligot Pascal Krop,Secret Service in Africa, The Sycamore Publishing, 1982, page 75

- ^ Auzias Dominique, Jean-Paul Labourdette, Sandra Fontaine,Benin Smart Little Country Guide, page 35

- ^ Omar Diop,Political parties and democratic transition process in Black Africa, Publibook, 2006, page 33

- ^ Philippe David,'The Benin, Karthala, 1998, page 63

- ^ Kerekou, the unavoidable, Jeune Afrique, 25 March 2010

- ^ Philippe David,'The Benin, Karthala, 1998, pages 64-65

- ^ Arnaud Zacharie, debt of Benin, a symbol of aborted democratic transition Committee for the Abolition of Third World debt

- ^ Barnaby Georges Gbagbo, Benin and the human rights, L'Harmattan, 2001, page 208

- ^ Philippe David, The Benin, Karthala, 1998, page 66

- ^ Philippe David, The Benin, Karthala, 1998, pages 67-68

- ^ Philippe David, The Benin, Karthala, 1998, page 68

- ^ Philippe David,'The Benin, Karthala, 1998, pages 69-70