Science

| Part of a series on |

| Science |

|---|

Science (from the Latin word scientia, meaning "knowledge")[1] is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.[2][3][4]

The earliest roots of science can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in around 3500 to 3000 BCE.[5][6] Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes.[5][6] After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages[7] but was preserved in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age.[8] The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived natural philosophy,[7][9] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[10] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[11][12][13][14] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape.[15][16][17]

Modern science is typically divided into three major branches that consist of the natural sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry, and physics), which study nature in the broadest sense; the social sciences (e.g., economics, psychology, and sociology), which study individuals and societies; and the formal sciences (e.g., logic, mathematics, and theoretical computer science), which study abstract concepts. There is disagreement,[18][19] however, on whether the formal sciences actually constitute a science as they do not rely on empirical evidence.[20] Disciplines that use existing scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as engineering and medicine, are described as applied sciences.[21][22][23][24]

Science is based on research, which is commonly conducted in academic and research institutions as well as in government agencies and companies. The practical impact of scientific research has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritizing the development of commercial products, armaments, health care, and environmental protection.

History

Science in a broad sense existed before the modern era and in many historical civilizations.[25] Modern science is distinct in its approach and successful in its results, so it now defines what science is in the strictest sense of the term.[3][5][26] Science in its original sense was a word for a type of knowledge, rather than a specialized word for the pursuit of such knowledge. In particular, it was the type of knowledge which people can communicate to each other and share. For example, knowledge about the working of natural things was gathered long before recorded history and led to the development of complex abstract thought. This is shown by the construction of complex calendars, techniques for making poisonous plants edible, public works at national scale, such as those which harnessed the floodplain of the Yangtse with reservoirs,[27] dams, and dikes, and buildings such as the Pyramids. However, no consistent conscious distinction was made between knowledge of such things, which are true in every community, and other types of communal knowledge, such as mythologies and legal systems. Metallurgy was known in prehistory, and the Vinča culture was the earliest known producer of bronze-like alloys. It is thought that early experimentation with heating and mixing of substances over time developed into alchemy.

Early cultures

Neither the words nor the concepts "science" and "nature" were part of the conceptual landscape in the ancient near east.[28] The ancient Mesopotamians used knowledge about the properties of various natural chemicals for manufacturing pottery, faience, glass, soap, metals, lime plaster, and waterproofing;[29] they also studied animal physiology, anatomy, and behavior for divinatory purposes[29] and made extensive records of the movements of astronomical objects for their study of astrology.[30] The Mesopotamians had intense interest in medicine[29] and the earliest medical prescriptions appear in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BCE – c. 2004 BCE).[31] Nonetheless, the Mesopotamians seem to have had little interest in gathering information about the natural world for the mere sake of gathering information[29] and mainly only studied scientific subjects which had obvious practical applications or immediate relevance to their religious system.[29]

Classical antiquity

In classical antiquity, there is no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, well-educated, usually upper-class, and almost universally male individuals performed various investigations into nature whenever they could afford the time.[32] Before the invention or discovery of the concept of "nature" (ancient Greek phusis) by the Pre-Socratic philosophers, the same words tend to be used to describe the natural "way" in which a plant grows,[33] and the "way" in which, for example, one tribe worships a particular god. For this reason, it is claimed these men were the first philosophers in the strict sense, and also the first people to clearly distinguish "nature" and "convention."[34]: 209 Natural philosophy, the precursor of natural science, was thereby distinguished as the knowledge of nature and things which are true for every community, and the name of the specialized pursuit of such knowledge was philosophy – the realm of the first philosopher-physicists. They were mainly speculators or theorists, particularly interested in astronomy. In contrast, trying to use knowledge of nature to imitate nature (artifice or technology, Greek technē) was seen by classical scientists as a more appropriate interest for lower class artisans.[35]

The early Greek philosophers of the Milesian school, which was founded by Thales of Miletus and later continued by his successors Anaximander and Anaximenes, were the first to attempt to explain natural phenomena without relying on the supernatural.[36] The Pythagoreans developed a complex number philosophy[37]: 467–68 and contributed significantly to the development of mathematical science.[37]: 465 The theory of atoms was developed by the Greek philosopher Leucippus and his student Democritus.[38][39] The Greek doctor Hippocrates established the tradition of systematic medical science[40][41] and is known as "The Father of Medicine".[42]

A turning point in the history of early philosophical science was Socrates' example of applying philosophy to the study of human matters, including human nature, the nature of political communities, and human knowledge itself. The Socratic method as documented by Plato's dialogues is a dialectic method of hypothesis elimination: better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. This was a reaction to the Sophist emphasis on rhetoric. The Socratic method searches for general, commonly held truths that shape beliefs and scrutinizes them to determine their consistency with other beliefs.[44] Socrates criticized the older type of study of physics as too purely speculative and lacking in self-criticism. Socrates was later, in the words of his Apology, accused of corrupting the youth of Athens because he did "not believe in the gods the state believes in, but in other new spiritual beings". Socrates refuted these claims,[45] but was sentenced to death.[46]: 30e

Aristotle later created a systematic programme of teleological philosophy: Motion and change is described as the actualization of potentials already in things, according to what types of things they are. In his physics, the Sun goes around the Earth, and many things have it as part of their nature that they are for humans. Each thing has a formal cause, a final cause, and a role in a cosmic order with an unmoved mover. The Socratics also insisted that philosophy should be used to consider the practical question of the best way to live for a human being (a study Aristotle divided into ethics and political philosophy). Aristotle maintained that man knows a thing scientifically "when he possesses a conviction arrived at in a certain way, and when the first principles on which that conviction rests are known to him with certainty".[47]

The Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos (310–230 BCE) was the first to propose a heliocentric model of the universe, with the Sun at the center and all the planets orbiting it.[48] Aristarchus's model was widely rejected because it was believed to violate the laws of physics.[48] The inventor and mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse made major contributions to the beginnings of calculus[49] and has sometimes been credited as its inventor,[49] although his proto-calculus lacked several defining features.[49] Pliny the Elder was a Roman writer and polymath, who wrote the seminal encyclopedia Natural History,[50][51][52] dealing with history, geography, medicine, astronomy, earth science, botany, and zoology.[50] Other scientists or proto-scientists in Antiquity were Theophrastus, Euclid, Herophilos, Hipparchus, Ptolemy, and Galen.

Medieval science

Because of the collapse of the Western Roman Empire due to the Migration Period an intellectual decline took place in the western part of Europe in the 400s. In contrast, the Byzantine Empire resisted the attacks from the barbarians, and preserved and improved upon the learning. John Philoponus, a Byzantine scholar in the 500s, was the first scholar ever to question Aristotle's teaching of physics and to note its flaws. John Philoponus' criticism of Aristotelian principles of physics served as an inspiration to medieval scholars as well as to Galileo Galilei who ten centuries later, during the Scientific Revolution, extensively cited Philoponus in his works while making the case as to why Aristotelian physics was flawed.[54][55]

During late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, the Aristotelian approach to inquiries on natural phenomena was used. Aristotle's four causes prescribed that four "why" questions should be answered in order to explain things scientifically.[56] Some ancient knowledge was lost, or in some cases kept in obscurity, during the fall of the Western Roman Empire and periodic political struggles. However, the general fields of science (or "natural philosophy" as it was called) and much of the general knowledge from the ancient world remained preserved through the works of the early Latin encyclopedists like Isidore of Seville.[57] However, Aristotle's original texts were eventually lost in Western Europe, and only one text by Plato was widely known, the Timaeus, which was the only Platonic dialogue, and one of the few original works of classical natural philosophy, available to Latin readers in the early Middle Ages. Another original work that gained influence in this period was Ptolemy's Almagest, which contains a geocentric description of the solar system.

During late antiquity, in the Byzantine empire many Greek classical texts were preserved. Many Syriac translations were done by groups such as the Nestorians and Monophysites.[58] They played a role when they translated Greek classical texts into Arabic under the Caliphate, during which many types of classical learning were preserved and in some cases improved upon.[58][a] In addition, the neighboring Sassanid Empire established the medical Academy of Gondeshapur where Greek, Syriac and Persian physicians established the most important medical center of the ancient world during the 6th and 7th centuries.[59]

The House of Wisdom was established in Abbasid-era Baghdad, Iraq,[60] where the Islamic study of Aristotelianism flourished. Al-Kindi (801–873) was the first of the Muslim Peripatetic philosophers, and is known for his efforts to introduce Greek and Hellenistic philosophy to the Arab world.[61] The Islamic Golden Age flourished from this time until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), as well as his predecessor Ibn Sahl, was familiar with Ptolemy's Optics, and used experiments as a means to gain knowledge.[b][62][63]: 463–65 Alhazen disproved Ptolemy's theory of vision,[64] but did not make any corresponding changes to Aristotle's metaphysics. Furthermore, doctors and alchemists such as the Persians Avicenna and Al-Razi also greatly developed the science of Medicine with the former writing the Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia used until the 18th century and the latter discovering multiple compounds like alcohol. Avicenna's canon is considered to be one of the most important publications in medicine and they both contributed significantly to the practice of experimental medicine, using clinical trials and experiments to back their claims.[65]

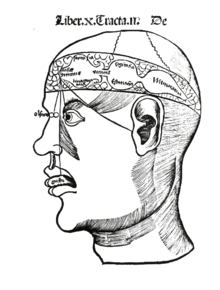

In Classical antiquity, Greek and Roman taboos had meant that dissection was usually banned in ancient times, but in Middle Ages it changed: medical teachers and students at Bologna began to open human bodies, and Mondino de Luzzi (c. 1275–1326) produced the first known anatomy textbook based on human dissection.[66][67]

By the eleventh century most of Europe had become Christian; stronger monarchies emerged; borders were restored; technological developments and agricultural innovations were made which increased the food supply and population. In addition, classical Greek texts started to be translated from Arabic and Greek into Latin, giving a higher level of scientific discussion in Western Europe.[7]

By 1088, the first university in Europe (the University of Bologna) had emerged from its clerical beginnings. Demand for Latin translations grew (for example, from the Toledo School of Translators); western Europeans began collecting texts written not only in Latin, but also Latin translations from Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew. Manuscript copies of Alhazen's Book of Optics also propagated across Europe before 1240,[68]: Intro. p. xx as evidenced by its incorporation into Vitello's Perspectiva. Avicenna's Canon was translated into Latin.[69] In particular, the texts of Aristotle, Ptolemy,[c] and Euclid, preserved in the Houses of Wisdom and also in the Byzantine Empire,[70] were sought amongst Catholic scholars. The influx of ancient texts caused the Renaissance of the 12th century and the flourishing of a synthesis of Catholicism and Aristotelianism known as Scholasticism in western Europe, which became a new geographic center of science. An experiment in this period would be understood as a careful process of observing, describing, and classifying.[71] One prominent scientist in this era was Roger Bacon. Scholasticism had a strong focus on revelation and dialectic reasoning, and gradually fell out of favour over the next centuries, as alchemy's focus on experiments that include direct observation and meticulous documentation slowly increased in importance.

Renaissance and early modern science

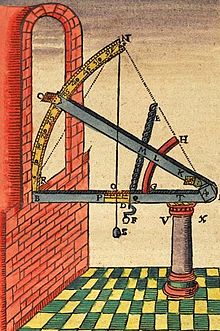

New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the Renaissance, both by challenging long-held metaphysical ideas on perception, as well as by contributing to the improvement and development of technology such as the camera obscura and the telescope. Before what we now know as the Renaissance started, Roger Bacon, Vitello, and John Peckham each built up a scholastic ontology upon a causal chain beginning with sensation, perception, and finally apperception of the individual and universal forms of Aristotle.[72] A model of vision later known as perspectivism was exploited and studied by the artists of the Renaissance. This theory uses only three of Aristotle's four causes: formal, material, and final.[73]

In the sixteenth century, Copernicus formulated a heliocentric model of the solar system unlike the geocentric model of Ptolemy's Almagest. This was based on a theorem that the orbital periods of the planets are longer as their orbs are farther from the centre of motion, which he found not to agree with Ptolemy's model.[74]

Kepler and others challenged the notion that the only function of the eye is perception, and shifted the main focus in optics from the eye to the propagation of light.[73][75]: 102 Kepler modelled the eye as a water-filled glass sphere with an aperture in front of it to model the entrance pupil. He found that all the light from a single point of the scene was imaged at a single point at the back of the glass sphere. The optical chain ends on the retina at the back of the eye.[d] Kepler is best known, however, for improving Copernicus' heliocentric model through the discovery of Kepler's laws of planetary motion. Kepler did not reject Aristotelian metaphysics, and described his work as a search for the Harmony of the Spheres.

Galileo made innovative use of experiment and mathematics. However, he became persecuted after Pope Urban VIII blessed Galileo to write about the Copernican system. Galileo had used arguments from the Pope and put them in the voice of the simpleton in the work "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems", which greatly offended Urban VIII.[77]

In Northern Europe, the new technology of the printing press was widely used to publish many arguments, including some that disagreed widely with contemporary ideas of nature. René Descartes and Francis Bacon published philosophical arguments in favor of a new type of non-Aristotelian science. Descartes emphasized individual thought and argued that mathematics rather than geometry should be used in order to study nature. Bacon emphasized the importance of experiment over contemplation. Bacon further questioned the Aristotelian concepts of formal cause and final cause, and promoted the idea that science should study the laws of "simple" natures, such as heat, rather than assuming that there is any specific nature, or "formal cause", of each complex type of thing. This new science began to see itself as describing "laws of nature". This updated approach to studies in nature was seen as mechanistic. Bacon also argued that science should aim for the first time at practical inventions for the improvement of all human life.

Age of Enlightenment

As a precursor to the Age of Enlightenment, Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz succeeded in developing a new physics, now referred to as classical mechanics, which could be confirmed by experiment and explained using mathematics. Leibniz also incorporated terms from Aristotelian physics, but now being used in a new non-teleological way, for example, "energy" and "potential" (modern versions of Aristotelian "energeia and potentia"). This implied a shift in the view of objects: Where Aristotle had noted that objects have certain innate goals that can be actualized, objects were now regarded as devoid of innate goals. In the style of Francis Bacon, Leibniz assumed that different types of things all work according to the same general laws of nature, with no special formal or final causes for each type of thing. It is during this period that the word "science" gradually became more commonly used to refer to a type of pursuit of a type of knowledge, especially knowledge of nature – coming close in meaning to the old term "natural philosophy."

During this time, the declared purpose and value of science became producing wealth and inventions that would improve human lives, in the materialistic sense of having more food, clothing, and other things. In Bacon's words, "the real and legitimate goal of sciences is the endowment of human life with new inventions and riches", and he discouraged scientists from pursuing intangible philosophical or spiritual ideas, which he believed contributed little to human happiness beyond "the fume of subtle, sublime, or pleasing speculation".[78]

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularization of science among an increasingly literate population. Philosophes introduced the public to many scientific theories, most notably through the Encyclopédie and the popularization of Newtonianism by Voltaire as well as by Émilie du Châtelet, the French translator of Newton's Principia.

Some historians have marked the 18th century as a drab period in the history of science;[79] however, the century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine, mathematics, and physics; the development of biological taxonomy; a new understanding of magnetism and electricity; and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline, which established the foundations of modern chemistry.

Enlightenment philosophers chose a short history of scientific predecessors – Galileo, Boyle, and Newton principally – as the guides and guarantors of their applications of the singular concept of nature and natural law to every physical and social field of the day. In this respect, the lessons of history and the social structures built upon it could be discarded.[80]

19th century

The nineteenth century is a particularly important period in the history of science since during this era many distinguishing characteristics of contemporary modern science began to take shape such as: transformation of the life and physical sciences, frequent use of precision instruments, emergence of terms like "biologist", "physicist", "scientist"; slowly moving away from antiquated labels like "natural philosophy" and "natural history", increased professionalization of those studying nature lead to reduction in amateur naturalists, scientists gained cultural authority over many dimensions of society, economic expansion and industrialization of numerous countries, thriving of popular science writings and emergence of science journals.[17]

Early in the 19th century, John Dalton suggested the modern atomic theory, based on Democritus's original idea of individible particles called atoms.

Both John Herschel and William Whewell systematized methodology: the latter coined the term scientist.[81] When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species he established evolution as the prevailing explanation of biological complexity. His theory of natural selection provided a natural explanation of how species originated, but this only gained wide acceptance a century later.

The laws of conservation of energy, conservation of momentum and conservation of mass suggested a highly stable universe where there could be little loss of resources. With the advent of the steam engine and the industrial revolution, there was, however, an increased understanding that all forms of energy as defined in physics were not equally useful: they did not have the same energy quality. This realization led to the development of the laws of thermodynamics, in which the cumulative energy quality of the universe is seen as constantly declining: the entropy of the universe increases over time.

The electromagnetic theory was also established in the 19th century, and raised new questions which could not easily be answered using Newton's framework. The phenomena that would allow the deconstruction of the atom were discovered in the last decade of the 19th century: the discovery of X-rays inspired the discovery of radioactivity. In the next year came the discovery of the first subatomic particle, the electron.

20th century

Einstein's theory of relativity and the development of quantum mechanics led to the replacement of classical mechanics with a new physics which contains two parts that describe different types of events in nature.

In the first half of the century, the development of antibiotics and artificial fertilizer made global human population growth possible. At the same time, the structure of the atom and its nucleus was discovered, leading to the release of "atomic energy" (nuclear power). In addition, the extensive use of technological innovation stimulated by the wars of this century led to revolutions in transportation (automobiles and aircraft), the development of ICBMs, a space race, and a nuclear arms race.

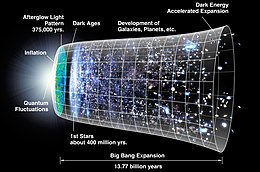

The molecular structure of DNA was discovered in 1953. The discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation in 1964 led to a rejection of the Steady State theory of the universe in favour of the Big Bang theory of Georges Lemaître.

The development of spaceflight in the second half of the century allowed the first astronomical measurements done on or near other objects in space, including manned landings on the Moon. Space telescopes lead to numerous discoveries in astronomy and cosmology.

Widespread use of integrated circuits in the last quarter of the 20th century combined with communications satellites led to a revolution in information technology and the rise of the global internet and mobile computing, including smartphones. The need for mass systematization of long, intertwined causal chains and large amounts of data led to the rise of the fields of systems theory and computer-assisted scientific modelling, which are partly based on the Aristotelian paradigm.[82]

Harmful environmental issues such as ozone depletion, acidification, eutrophication and climate change came to the public's attention in the same period, and caused the onset of environmental science and environmental technology.

21st century

The Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, determining the sequence of nucleotide base pairs that make up human DNA, and identifying and mapping all of the genes of the human genome.[83] Induced pluripotent stem cells were developed in 2006, a technology allowing adult cells to be transformed into stem cells capable of giving rise to any cell type found in the body, potentially of huge importance to the field of regenerative medicine.[84]

With the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, the last particle predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics was found. In 2015, gravitational waves, predicted by general relativity a century before, were first observed.[85][86]

Branches of science

Modern science is commonly divided into three major branches that consist of the natural sciences, social sciences, and formal sciences. Each of these branches comprise various specialized yet overlapping scientific disciplines that often possess their own nomenclature and expertise.[87] Both natural and social sciences are empirical sciences[88] as their knowledge are based on empirical observations and are capable of being tested for its validity by other researchers working under the same conditions.[89]

There are also closely related disciplines that use science, such as engineering and medicine, which are sometimes described as applied sciences. The relationships between the branches of science are summarized by the following table.

Formal science

Formal science is involved in the study of formal systems. It includes mathematics,[90][91] systems theory, theoretical computer science, and artificial intelligence.[92] The formal sciences share similarities with the other two branches by relying on objective, careful, and systematic study of an area of knowledge. They are, however, different from the empirical sciences as they rely exclusively on deductive reasoning, without the need for empirical evidence, to verify their abstract concepts.[20][93][89] The formal sciences are therefore a priori disciplines and because of this, there is disagreement on whether they actually constitute a science.[18][19] Nevertheless, the formal sciences play an important role in the empirical sciences. Calculus, for example, was initially invented to understand motion in physics.[94] Natural and social sciences that rely heavily on mathematical applications include mathematical physics, mathematical chemistry, mathematical biology, mathematical finance, and mathematical economics.

Natural science

Natural science is concerned with the description, prediction, and understanding of natural phenomena based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. It can be divided into two main branches: life science (or biological science) and physical science. Physical science is subdivided into branches, including physics, chemistry, astronomy and earth science. These two branches may be further divided into more specialized disciplines. Modern natural science is the successor to the natural philosophy that began in Ancient Greece. Galileo, Descartes, Bacon, and Newton debated the benefits of using approaches which were more mathematical and more experimental in a methodical way. Still, philosophical perspectives, conjectures, and presuppositions, often overlooked, remain necessary in natural science.[95] Systematic data collection, including discovery science, succeeded natural history, which emerged in the 16th century by describing and classifying plants, animals, minerals, and so on.[96] Today, "natural history" suggests observational descriptions aimed at popular audiences.[97]

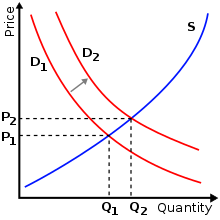

Social science

Social science is concerned with society and the relationships among individuals within a society. It has many branches that include, but are not limited to, anthropology, archaeology, communication studies, economics, history, human geography, jurisprudence, linguistics, political science, psychology, public health, and sociology. Social scientists may adopt various philosophical theories to study individuals and society. For example, positivist social scientists use methods resembling those of the natural sciences as tools for understanding society, and so define science in its stricter modern sense. Interpretivist social scientists, by contrast, may use social critique or symbolic interpretation rather than constructing empirically falsifiable theories, and thus treat science in its broader sense. In modern academic practice, researchers are often eclectic, using multiple methodologies (for instance, by combining both quantitative and qualitative research). The term "social research" has also acquired a degree of autonomy as practitioners from various disciplines share in its aims and methods.

Scientific research

Scientific research can be labeled as either basic or applied research. Basic research is the search for knowledge and applied research is the search for solutions to practical problems using this knowledge. Although some scientific research is applied research into specific problems, a great deal of our understanding comes from the curiosity-driven undertaking of basic research. This leads to options for technological advance that were not planned or sometimes even imaginable. This point was made by Michael Faraday when allegedly in response to the question "what is the use of basic research?" he responded: "Sir, what is the use of a new-born child?".[98] For example, research into the effects of red light on the human eye's rod cells did not seem to have any practical purpose; eventually, the discovery that our night vision is not troubled by red light would lead search and rescue teams (among others) to adopt red light in the cockpits of jets and helicopters.[99] Finally, even basic research can take unexpected turns, and there is some sense in which the scientific method is built to harness luck.

Scientific method

Scientific research involves using the scientific method, which seeks to objectively explain the events of nature in a reproducible way.[100] An explanatory thought experiment or hypothesis is put forward as explanation using principles such as parsimony (also known as "Occam's Razor") and are generally expected to seek consilience – fitting well with other accepted facts related to the phenomena.[101] This new explanation is used to make falsifiable predictions that are testable by experiment or observation. The predictions are to be posted before a confirming experiment or observation is sought, as proof that no tampering has occurred. Disproof of a prediction is evidence of progress.[100][102] This is done partly through observation of natural phenomena, but also through experimentation that tries to simulate natural events under controlled conditions as appropriate to the discipline (in the observational sciences, such as astronomy or geology, a predicted observation might take the place of a controlled experiment). Experimentation is especially important in science to help establish causal relationships (to avoid the correlation fallacy).

When a hypothesis proves unsatisfactory, it is either modified or discarded.[103] If the hypothesis survived testing, it may become adopted into the framework of a scientific theory, a logically reasoned, self-consistent model or framework for describing the behavior of certain natural phenomena. A theory typically describes the behavior of much broader sets of phenomena than a hypothesis; commonly, a large number of hypotheses can be logically bound together by a single theory. Thus a theory is a hypothesis explaining various other hypotheses. In that vein, theories are formulated according to most of the same scientific principles as hypotheses. In addition to testing hypotheses, scientists may also generate a model, an attempt to describe or depict the phenomenon in terms of a logical, physical or mathematical representation and to generate new hypotheses that can be tested, based on observable phenomena.[104]

While performing experiments to test hypotheses, scientists may have a preference for one outcome over another, and so it is important to ensure that science as a whole can eliminate this bias.[105][106] This can be achieved by careful experimental design, transparency, and a thorough peer review process of the experimental results as well as any conclusions.[107][108] After the results of an experiment are announced or published, it is normal practice for independent researchers to double-check how the research was performed, and to follow up by performing similar experiments to determine how dependable the results might be.[109] Taken in its entirety, the scientific method allows for highly creative problem solving while minimizing any effects of subjective bias on the part of its users (especially the confirmation bias).[110]

Role of mathematics

Mathematics is essential in the formation of hypotheses, theories, and laws[111] in the natural and social sciences. For example, it is used in quantitative scientific modeling, which can generate new hypotheses and predictions to be tested. It is also used extensively in observing and collecting measurements. Statistics, a branch of mathematics, is used to summarize and analyze data, which allow scientists to assess the reliability and variability of their experimental results.

Computational science applies computing power to simulate real-world situations, enabling a better understanding of scientific problems than formal mathematics alone can achieve. According to the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, computation is now as important as theory and experiment in advancing scientific knowledge.[112]

Verifiability

John Ziman points out that intersubjective verifiability is fundamental to the creation of all scientific knowledge.[113] Ziman shows how scientists can identify patterns to each other across centuries; he refers to this ability as "perceptual consensibility."[113] He then makes consensibility, leading to consensus, the touchstone of reliable knowledge.[114]

Metascience

Meta-science refers to the systematic investigation of the scientific enterprise: in other words, the use of scientific methodology to study science itself. It is also known as "research on research" or "the science of science".[115] Metascience only began to emerge as a field of research in the late twentieth century. While not counted among the three branches of science, metascience aims to improve the quality of all scientific research.

Philosophy of science

Scientists usually take for granted a set of basic assumptions that are needed to justify the scientific method: (1) that there is an objective reality shared by all rational observers; (2) that this objective reality is governed by natural laws; (3) that these laws can be discovered by means of systematic observation and experimentation.[3] Philosophy of science seeks a deep understanding of what these underlying assumptions mean and whether they are valid.

The belief that scientific theories should and do represent metaphysical reality is known as realism. It can be contrasted with anti-realism, the view that the success of science does not depend on it being accurate about unobservable entities such as electrons. One form of anti-realism is idealism, the belief that the mind or consciousness is the most basic essence, and that each mind generates its own reality.[e] In an idealistic world view, what is true for one mind need not be true for other minds.

There are different schools of thought in philosophy of science. The most popular position is empiricism,[f] which holds that knowledge is created by a process involving observation and that scientific theories are the result of generalizations from such observations.[116] Empiricism generally encompasses inductivism, a position that tries to explain the way general theories can be justified by the finite number of observations humans can make and hence the finite amount of empirical evidence available to confirm scientific theories. This is necessary because the number of predictions those theories make is infinite, which means that they cannot be known from the finite amount of evidence using deductive logic only. Many versions of empiricism exist, with the predominant ones being Bayesianism[117] and the hypothetico-deductive method.[116]

Empiricism has stood in contrast to rationalism, the position originally associated with Descartes, which holds that knowledge is created by the human intellect, not by observation.[118] Critical rationalism is a contrasting 20th-century approach to science, first defined by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper. Popper rejected the way that empiricism describes the connection between theory and observation. He claimed that theories are not generated by observation, but that observation is made in the light of theories and that the only way a theory can be affected by observation is when it comes in conflict with it.[119] Popper proposed replacing verifiability with falsifiability as the landmark of scientific theories and replacing induction with falsification as the empirical method.[119] Popper further claimed that there is actually only one universal method, not specific to science: the negative method of criticism, trial and error.[120] It covers all products of the human mind, including science, mathematics, philosophy, and art.[121]

Another approach, instrumentalism, colloquially termed "shut up and multiply,"[122] emphasizes the utility of theories as instruments for explaining and predicting phenomena.[123] It views scientific theories as black boxes with only their input (initial conditions) and output (predictions) being relevant. Consequences, theoretical entities, and logical structure are claimed to be something that should simply be ignored and that scientists shouldn't make a fuss about (see interpretations of quantum mechanics). Close to instrumentalism is constructive empiricism, according to which the main criterion for the success of a scientific theory is whether what it says about observable entities is true.

Thomas Kuhn argued that the process of observation and evaluation takes place within a paradigm, a logically consistent "portrait" of the world that is consistent with observations made from its framing. He characterized normal science as the process of observation and "puzzle solving" which takes place within a paradigm, whereas revolutionary science occurs when one paradigm overtakes another in a paradigm shift.[124] Each paradigm has its own distinct questions, aims, and interpretations. The choice between paradigms involves setting two or more "portraits" against the world and deciding which likeness is most promising. A paradigm shift occurs when a significant number of observational anomalies arise in the old paradigm and a new paradigm makes sense of them. That is, the choice of a new paradigm is based on observations, even though those observations are made against the background of the old paradigm. For Kuhn, acceptance or rejection of a paradigm is a social process as much as a logical process. Kuhn's position, however, is not one of relativism.[125]

Finally, another approach often cited in debates of scientific skepticism against controversial movements like "creation science" is methodological naturalism. Its main point is that a difference between natural and supernatural explanations should be made and that science should be restricted methodologically to natural explanations.[126][g] That the restriction is merely methodological (rather than ontological) means that science should not consider supernatural explanations itself, but should not claim them to be wrong either. Instead, supernatural explanations should be left a matter of personal belief outside the scope of science. Methodological naturalism maintains that proper science requires strict adherence to empirical study and independent verification as a process for properly developing and evaluating explanations for observable phenomena.[127] The absence of these standards, arguments from authority, biased observational studies and other common fallacies are frequently cited by supporters of methodological naturalism as characteristic of the non-science they criticize.

Certainty and science

A scientific theory is empirical[f][128] and is always open to falsification if new evidence is presented. That is, no theory is ever considered strictly certain as science accepts the concept of fallibilism.[h] The philosopher of science Karl Popper sharply distinguished truth from certainty. He wrote that scientific knowledge "consists in the search for truth," but it "is not the search for certainty ... All human knowledge is fallible and therefore uncertain.[129]

New scientific knowledge rarely results in vast changes in our understanding. According to psychologist Keith Stanovich, it may be the media's overuse of words like "breakthrough" that leads the public to imagine that science is constantly proving everything it thought was true to be false.[99] While there are such famous cases as the theory of relativity that required a complete reconceptualization, these are extreme exceptions. Knowledge in science is gained by a gradual synthesis of information from different experiments by various researchers across different branches of science; it is more like a climb than a leap.[99] Theories vary in the extent to which they have been tested and verified, as well as their acceptance in the scientific community.[i] For example, heliocentric theory, the theory of evolution, relativity theory, and germ theory still bear the name "theory" even though, in practice, they are considered factual.[130] Philosopher Barry Stroud adds that, although the best definition for "knowledge" is contested, being skeptical and entertaining the possibility that one is incorrect is compatible with being correct. Therefore, scientists adhering to proper scientific approaches will doubt themselves even once they possess the truth.[131] The fallibilist C. S. Peirce argued that inquiry is the struggle to resolve actual doubt and that merely quarrelsome, verbal, or hyperbolic doubt is fruitless[132] – but also that the inquirer should try to attain genuine doubt rather than resting uncritically on common sense.[133] He held that the successful sciences trust not to any single chain of inference (no stronger than its weakest link) but to the cable of multiple and various arguments intimately connected.[134]

Stanovich also asserts that science avoids searching for a "magic bullet"; it avoids the single-cause fallacy. This means a scientist would not ask merely "What is the cause of ...", but rather "What are the most significant causes of ...". This is especially the case in the more macroscopic fields of science (e.g. psychology, physical cosmology).[99] Research often analyzes few factors at once, but these are always added to the long list of factors that are most important to consider.[99] For example, knowing the details of only a person's genetics, or their history and upbringing, or the current situation may not explain a behavior, but a deep understanding of all these variables combined can be very predictive.

Fringe science, pseudoscience, and junk science

An area of study or speculation that masquerades as science in an attempt to claim a legitimacy that it would not otherwise be able to achieve is sometimes referred to as pseudoscience, fringe science, or junk science.[j] Physicist Richard Feynman coined the term "cargo cult science" for cases in which researchers believe they are doing science because their activities have the outward appearance of science but actually lack the "kind of utter honesty" that allows their results to be rigorously evaluated.[135] Various types of commercial advertising, ranging from hype to fraud, may fall into these categories. Science has been described as "the most important tool" for separating valid claims from invalid ones.[136]

There can also be an element of political or ideological bias on all sides of scientific debates. Sometimes, research may be characterized as "bad science," research that may be well-intended but is actually incorrect, obsolete, incomplete, or over-simplified expositions of scientific ideas. The term "scientific misconduct" refers to situations such as where researchers have intentionally misrepresented their published data or have purposely given credit for a discovery to the wrong person.[137]

Scientific literature

Scientific research is published in an enormous range of scientific literature.[138] Scientific journals communicate and document the results of research carried out in universities and various other research institutions, serving as an archival record of science. The first scientific journals, Journal des Sçavans followed by the Philosophical Transactions, began publication in 1665. Since that time the total number of active periodicals has steadily increased. In 1981, one estimate for the number of scientific and technical journals in publication was 11,500.[139] The United States National Library of Medicine currently indexes 5,516 journals that contain articles on topics related to the life sciences. Although the journals are in 39 languages, 91 percent of the indexed articles are published in English.[140]

Most scientific journals cover a single scientific field and publish the research within that field; the research is normally expressed in the form of a scientific paper. Science has become so pervasive in modern societies that it is generally considered necessary to communicate the achievements, news, and ambitions of scientists to a wider populace.

Science magazines such as New Scientist, Science & Vie, and Scientific American cater to the needs of a much wider readership and provide a non-technical summary of popular areas of research, including notable discoveries and advances in certain fields of research. Science books engage the interest of many more people. Tangentially, the science fiction genre, primarily fantastic in nature, engages the public imagination and transmits the ideas, if not the methods, of science.

Recent efforts to intensify or develop links between science and non-scientific disciplines such as literature or more specifically, poetry, include the Creative Writing Science resource developed through the Royal Literary Fund.[141]

Practical impacts

Discoveries in fundamental science can be world-changing. For example:

Research Impact Static electricity and magnetism (c. 1600)

Electric current (18th century)All electric appliances, dynamos, electric power stations, modern electronics, including electric lighting, television, electric heating, transcranial magnetic stimulation, deep brain stimulation, magnetic tape, loudspeaker, and the compass and lightning rod. Diffraction (1665) Optics, hence fiber optic cable (1840s), modern intercontinental communications, and cable TV and internet. Germ theory (1700) Hygiene, leading to decreased transmission of infectious diseases; antibodies, leading to techniques for disease diagnosis and targeted anticancer therapies. Vaccination (1798) Leading to the elimination of most infectious diseases from developed countries and the worldwide eradication of smallpox. Photovoltaic effect (1839) Solar cells (1883), hence solar power, solar powered watches, calculators and other devices. The strange orbit of Mercury (1859) and other research

leading to special (1905) and general relativity (1916)Satellite-based technology such as GPS (1973), satnav and satellite communications.[k] Radio waves (1887) Radio had become used in innumerable ways beyond its better-known areas of telephony, and broadcast television (1927) and radio (1906) entertainment. Other uses included – emergency services, radar (navigation and weather prediction), medicine, astronomy, wireless communications, geophysics, and networking. Radio waves also led researchers to adjacent frequencies such as microwaves, used worldwide for heating and cooking food. Radioactivity (1896) and antimatter (1932) Cancer treatment (1896), Radiometric dating (1905), nuclear reactors (1942) and weapons (1945), mineral exploration, PET scans (1961), and medical research (via isotopic labeling). X-rays (1896) Medical imaging, including computed tomography. Crystallography and quantum mechanics (1900) Semiconductor devices (1906), hence modern computing and telecommunications including the integration with wireless devices: the mobile phone,[k] LED lamps and lasers. Plastics (1907) Starting with Bakelite, many types of artificial polymers for numerous applications in industry and daily life. Antibiotics (1880s, 1928) Salvarsan, Penicillin, doxycycline etc. Nuclear magnetic resonance (1930s) Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1946), magnetic resonance imaging (1971), functional magnetic resonance imaging (1990s).

Scientific community

The scientific community is a group of all interacting scientists, along with their respective societies and institutions.

Scientists

Scientists are individuals who conduct scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of interest.[142][143] The term scientist was coined by William Whewell in 1833. In modern times, many professional scientists are trained in an academic setting and upon completion, attain an academic degree, with the highest degree being a doctorate such as a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD),[144] Doctor of Medicine (MD), or Doctor of Engineering (DEng). Many scientists pursue careers in various sectors of the economy such as academia, industry, government, and nonprofit organizations.[145][146][147]

Scientists exhibit a strong curiosity about reality, with some scientists having a desire to apply scientific knowledge for the benefit of health, nations, environment, or industries. Other motivations include recognition by their peers and prestige. The Nobel Prize, a widely regarded prestigious award,[148] is awarded annually to those who have achieved scientific advances in the fields of medicine, physics, chemistry, and economics.

Women in science

Science has historically been a male-dominated field, with some notable exceptions.[l] Women faced considerable discrimination in science, much as they did in other areas of male-dominated societies, such as frequently being passed over for job opportunities and denied credit for their work.[m] For example, Christine Ladd (1847–1930) was able to enter a PhD program as "C. Ladd"; Christine "Kitty" Ladd completed the requirements in 1882, but was awarded her degree only in 1926, after a career which spanned the algebra of logic (see truth table), color vision, and psychology. Her work preceded notable researchers like Ludwig Wittgenstein and Charles Sanders Peirce. The achievements of women in science have been attributed to their defiance of their traditional role as laborers within the domestic sphere.[150]

In the late 20th century, active recruitment of women and elimination of institutional discrimination on the basis of sex greatly increased the number of women scientists, but large gender disparities remain in some fields; in the early 21st century over half of new biologists were female, while 80% of PhDs in physics are given to men.[citation needed] In the early part of the 21st century, women in the United States earned 50.3% of bachelor's degrees, 45.6% of master's degrees, and 40.7% of PhDs in science and engineering fields. They earned more than half of the degrees in psychology (about 70%), social sciences (about 50%), and biology (about 50-60%) but earned less than half the degrees in the physical sciences, earth sciences, mathematics, engineering, and computer science.[151] Lifestyle choice also plays a major role in female engagement in science; women with young children are 28% less likely to take tenure-track positions due to work-life balance issues,[152] and female graduate students' interest in careers in research declines dramatically over the course of graduate school, whereas that of their male colleagues remains unchanged.[153]

Learned societies

Learned societies for the communication and promotion of scientific thought and experimentation have existed since the Renaissance.[154] Many scientists belong to a learned society that promotes their respective scientific discipline, profession, or group of related disciplines.[155] Membership may be open to all, may require possession of some scientific credentials, or may be an honor conferred by election.[156] Most scientific societies are non-profit organizations, and many are professional associations. Their activities typically include holding regular conferences for the presentation and discussion of new research results and publishing or sponsoring academic journals in their discipline. Some also act as professional bodies, regulating the activities of their members in the public interest or the collective interest of the membership. Scholars in the sociology of science[who?] argue that learned societies are of key importance and their formation assists in the emergence and development of new disciplines or professions.

The professionalization of science, begun in the 19th century, was partly enabled by the creation of distinguished academy of sciences in a number of countries such as the Italian Accademia dei Lincei in 1603,[157] the British Royal Society in 1660, the French Académie des Sciences in 1666,[158] the American National Academy of Sciences in 1863, the German Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in 1911, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1928. International scientific organizations, such as the International Council for Science, have since been formed to promote cooperation between the scientific communities of different nations.

Science and the public

Science policy

Science policy is an area of public policy concerned with the policies that affect the conduct of the scientific enterprise, including research funding, often in pursuance of other national policy goals such as technological innovation to promote commercial product development, weapons development, health care and environmental monitoring. Science policy also refers to the act of applying scientific knowledge and consensus to the development of public policies. Science policy thus deals with the entire domain of issues that involve the natural sciences. In accordance with public policy being concerned about the well-being of its citizens, science policy's goal is to consider how science and technology can best serve the public.

State policy has influenced the funding of public works and science for thousands of years, particularly within civilizations with highly organized governments such as imperial China and the Roman Empire. Prominent historical examples include the Great Wall of China, completed over the course of two millennia through the state support of several dynasties, and the Grand Canal of the Yangtze River, an immense feat of hydraulic engineering begun by Sunshu Ao (孫叔敖 7th c. BCE), Ximen Bao (西門豹 5th c.BCE), and Shi Chi (4th c. BCE). This construction dates from the 6th century BCE under the Sui Dynasty and is still in use today. In China, such state-supported infrastructure and scientific research projects date at least from the time of the Mohists, who inspired the study of logic during the period of the Hundred Schools of Thought and the study of defensive fortifications like the Great Wall of China during the Warring States period.

Public policy can directly affect the funding of capital equipment and intellectual infrastructure for industrial research by providing tax incentives to those organizations that fund research. Vannevar Bush, director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development for the United States government, the forerunner of the National Science Foundation, wrote in July 1945 that "Science is a proper concern of government."[159]

Funding of science

Scientific research is often funded through a competitive process in which potential research projects are evaluated and only the most promising receive funding. Such processes, which are run by government, corporations, or foundations, allocate scarce funds. Total research funding in most developed countries is between 1.5% and 3% of GDP.[160] In the OECD, around two-thirds of research and development in scientific and technical fields is carried out by industry, and 20% and 10% respectively by universities and government. The government funding proportion in certain industries is higher, and it dominates research in social science and humanities. Similarly, with some exceptions (e.g. biotechnology) government provides the bulk of the funds for basic scientific research. Many governments have dedicated agencies to support scientific research. Prominent scientific organizations include the National Science Foundation in the United States, the National Scientific and Technical Research Council in Argentina, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique in France, the Max Planck Society and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft in Germany, and CSIC in Spain. In commercial research and development, all but the most research-oriented corporations focus more heavily on near-term commercialisation possibilities rather than "blue-sky" ideas or technologies (such as nuclear fusion).

Public awareness of science

The public awareness of science relates to the attitudes, behaviors, opinions, and activities that make up the relations between science and the general public. it integrates various themes and activities such as science communication, science museums, science festivals, science fairs, citizen science, and science in popular culture. Social scientists have devised various metrics to measure the public understanding of science such as factual knowledge, self-reported knowledge, and structural knowledge.[161][162]

Science journalism

The mass media face a number of pressures that can prevent them from accurately depicting competing scientific claims in terms of their credibility within the scientific community as a whole. Determining how much weight to give different sides in a scientific debate may require considerable expertise regarding the matter.[163] Few journalists have real scientific knowledge, and even beat reporters who know a great deal about certain scientific issues may be ignorant about other scientific issues that they are suddenly asked to cover.[164][165]

Politicization of science

Politicization of science occurs when government, business, or advocacy groups use legal or economic pressure to influence the findings of scientific research or the way it is disseminated, reported, or interpreted. Many factors can act as facets of the politicization of science such as populist anti-intellectualism, perceived threats to religious beliefs, postmodernist subjectivism, and fear for business interests.[166] Politicization of science is usually accomplished when scientific information is presented in a way that emphasizes the uncertainty associated with the scientific evidence.[167] Tactics such as shifting conversation, failing to acknowledge facts, and capitalizing on doubt of scientific consensus have been used to gain more attention for views that have been undermined by scientific evidence.[168] Examples of issues that have involved the politicization of science include the global warming controversy, health effects of pesticides, and health effects of tobacco.[168][169]

See also

- Antiquarian science books

- Criticism of science

- Human timeline

- Index of branches of science

- Life timeline

- List of scientific occupations

- Normative science

- Outline of science

- Pathological science

- Protoscience

- Science in popular culture

- Science wars

- Scientific dissent

- Sociology of scientific knowledge

- Wissenschaft – all areas of scholarly study, including both sciences and non-sciences

Notes

- ^ Alhacen had access to the optics books of Euclid and Ptolemy, as is shown by the title of his lost work A Book in which I have Summarized the Science of Optics from the Two Books of Euclid and Ptolemy, to which I have added the Notions of the First Discourse which is Missing from Ptolemy's Book From Ibn Abi Usaibia's catalog, as cited in (Smith 2001) harv error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSmith2001 (help): 91(vol .1), p. xv

- ^ "[Ibn al-Haytham] followed Ptolemy's bridge building ... into a grand synthesis of light and vision. Part of his effort consisted in devising ranges of experiments, of a kind probed before but now undertaken on larger scale."— Cohen 2010, p. 59

- ^ The translator, Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114–1187), inspired by his love of the Almagest, came to Toledo, where he knew he could find the Almagest in Arabic. There he found Arabic books of every description, and learned Arabic in order to translate these books into Latin, being aware of 'the poverty of the Latins'. —As cited by Burnett, Charles (2002). "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century". Science in Context. 14: 249–88. doi:10.1017/S0269889701000096.

- ^ Kepler, Johannes (1604) Ad Vitellionem paralipomena, quibus astronomiae pars opticae traditur (Supplements to Witelo, in which the optical part of astronomy is treated) as cited in Smith, A. Mark (January 1, 2004). "What Is the History of Medieval Optics Really about?". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 148 (2): 180–94. JSTOR 1558283. PMID 15338543.

- The full title translation is from p. 60 of James R. Voelkel (2001) Johannes Kepler and the New Astronomy Oxford University Press. Kepler was driven to this experiment after observing the partial solar eclipse at Graz, July 10, 1600. He used Tycho Brahe's method of observation, which was to project the image of the Sun on a piece of paper through a pinhole aperture, instead of looking directly at the Sun. He disagreed with Brahe's conclusion that total eclipses of the Sun were impossible, because there were historical accounts of total eclipses. Instead he deduced that the size of the aperture controls the sharpness of the projected image (the larger the aperture, the more accurate the image – this fact is now fundamental for optical system design). Voelkel, p. 61, notes that Kepler's experiments produced the first correct account of vision and the eye, because he realized he could not accurately write about astronomical observation by ignoring the eye.

- ^ This realization is the topic of intersubjective verifiability, as recounted, for example, by Max Born (1949, 1965) Natural Philosophy of Cause and Chance, who points out that all knowledge, including natural or social science, is also subjective. p. 162: "Thus it dawned upon me that fundamentally everything is subjective, everything without exception. That was a shock."

- ^ a b In his investigation of the law of falling bodies, Galileo (1638) serves as example for scientific investigation: Two New Sciences "A piece of wooden moulding or scantling, about 12 cubits long, half a cubit wide, and three finger-breadths thick, was taken; on its edge was cut a channel a little more than one finger in breadth; having made this groove very straight, smooth, and polished, and having lined it with parchment, also as smooth and polished as possible, we rolled along it a hard, smooth, and very round bronze ball. Having placed this board in a sloping position, by lifting one end some one or two cubits above the other, we rolled the ball, as I was just saying, along the channel, noting, in a manner presently to be described, the time required to make the descent. We ... now rolled the ball only one-quarter the length of the channel; and having measured the time of its descent, we found it precisely one-half of the former. Next we tried other distances, comparing the time for the whole length with that for the half, or with that for two-thirds, or three-fourths, or indeed for any fraction; in such experiments, repeated many, many, times." Galileo solved the problem of time measurement by weighing a jet of water collected during the descent of the bronze ball, as stated in his Two New Sciences.

- ^ credits Willard Van Orman Quine (1969) "Epistemology Naturalized" Ontological Relativity and Other Essays New York: Columbia University Press, as well as John Dewey, with the basic ideas of naturalism – Naturalized Epistemology, but Godfrey-Smith diverges from Quine's position: according to Godfrey-Smith, "A naturalist can think that science can contribute to answers to philosophical questions, without thinking that philosophical questions can be replaced by science questions.".

- ^ "No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong." —Albert Einstein, noted by Alice Calaprice (ed. 2005) The New Quotable Einstein Princeton University Press and Hebrew University of Jerusalem, ISBN 0-691-12074-9 p. 291. Calaprice denotes this not as an exact quotation, but as a paraphrase of a translation of A. Einstein's "Induction and Deduction". Collected Papers of Albert Einstein 7 Document 28. Volume 7 is The Berlin Years: Writings, 1918–1921. A. Einstein; M. Janssen, R. Schulmann, et al., eds.

- ^ Fleck, Ludwik (1979). Trenn, Thaddeus J.; Merton, Robert K (eds.). Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-25325-1. Claims that before a specific fact "existed", it had to be created as part of a social agreement within a community. Steven Shapin (1980) "A view of scientific thought" Science ccvii (Mar 7, 1980) 1065–66 states "[To Fleck,] facts are invented, not discovered. Moreover, the appearance of scientific facts as discovered things is itself a social construction: a made thing. "

- ^ "Pseudoscientific – pretending to be scientific, falsely represented as being scientific", from the Oxford American Dictionary, published by the Oxford English Dictionary; Hansson, Sven Ove (1996)."Defining Pseudoscience", Philosophia Naturalis, 33: 169–76, as cited in "Science and Pseudo-science" (2008) in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Stanford article states: "Many writers on pseudoscience have emphasized that pseudoscience is non-science posing as science. The foremost modern classic on the subject (Gardner 1957) bears the title Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. According to Brian Baigrie (1988, 438), "[w]hat is objectionable about these beliefs is that they masquerade as genuinely scientific ones." These and many other authors assume that to be pseudoscientific, an activity or a teaching has to satisfy the following two criteria (Hansson 1996): (1) it is not scientific, and (2) its major proponents try to create the impression that it is scientific".

- For example, Hewitt et al. Conceptual Physical Science Addison Wesley; 3 edition (July 18, 2003) ISBN 0-321-05173-4, Bennett et al. The Cosmic Perspective 3e Addison Wesley; 3 edition (July 25, 2003) ISBN 0-8053-8738-2; See also, e.g., Gauch HG Jr. Scientific Method in Practice (2003).

- A 2006 National Science Foundation report on Science and engineering indicators quoted Michael Shermer's (1997) definition of pseudoscience: '"claims presented so that they appear [to be] scientific even though they lack supporting evidence and plausibility" (p. 33). In contrast, science is "a set of methods designed to describe and interpret observed and inferred phenomena, past or present, and aimed at building a testable body of knowledge open to rejection or confirmation" (p. 17)'.Shermer M. (1997). Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-3090-3. as cited by National Science Board. National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics (2006). "Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". Science and engineering indicators 2006. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "A pretended or spurious science; a collection of related beliefs about the world mistakenly regarded as being based on scientific method or as having the status that scientific truths now have," from the Oxford English Dictionary, second edition 1989.

- ^ a b Evicting Einstein, March 26, 2004, NASA. "Both [relativity and quantum mechanics] are extremely successful. The Global Positioning System (GPS), for instance, wouldn't be possible without the theory of relativity. Computers, telecommunications, and the Internet, meanwhile, are spin-offs of quantum mechanics."

- ^ Women in science have included:

- Hypatia (c. 350–415 CE), of the Library of Alexandria.

- Trotula of Salerno, a physician c. 1060 CE.

- Caroline Herschel, one of the first professional astronomers of the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Christine Ladd-Franklin, a doctoral student of C.S. Peirce, who published Wittgenstein's proposition 5.101 in her dissertation, 40 years before Wittgenstein's publication of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

- Henrietta Leavitt, a professional human computer and astronomer, who first published the significant relationship between the luminosity of Cepheid variable stars and their distance from Earth. This allowed Hubble to make the discovery of the expanding universe, which led to the Big Bang theory.

- Emmy Noether, who proved the conservation of energy and other constants of motion in 1915.

- Marie Curie, who made discoveries relating to radioactivity along with her husband, and for whom Curium is named.

- Rosalind Franklin, who worked with X-ray diffraction.

- Jocelyn Bell Burnell, at first not allowed to study science in her preparatory school, persisted, and was the first to observe and precisely analyse the radio pulsars, for which her supervisor was recognized by the 1974 Nobel prize in Physics. (Later awarded a Special Breakthrough prize in Physics in 2018, she donated the cash award in order that women, ethnic minority, and refugee students might become physics researchers.)

- In 2018 Donna Strickland became the third woman (the second being Maria Goeppert-Mayer in 1962) to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, for her work in chirped pulse amplification of lasers. Frances H. Arnold became the fifth woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the directed evolution of enzymes.

- ^ Nina Byers, Contributions of 20th Century Women to Physics which provides details on 83 female physicists of the 20th century. By 1976, more women were physicists, and the 83 who were detailed were joined by other women in noticeably larger numbers.

References

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "science". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Wilson, E.O. (1999). "The natural sciences". Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Reprint ed.). New York, New York: Vintage. pp. 49–71. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- ^ a b c Heilbron, J.L. (editor-in-chief) (2003). "Preface". The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–X. ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "science". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

3 a: knowledge or a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through scientific method b: such knowledge or such a system of knowledge concerned with the physical world and its phenomena.

- ^ a b c Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Science before the Greeks". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ a b Grant, Edward (2007). "Ancient Egypt to Plato". A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-052-1-68957-1.

- ^ a b c Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The revival of learning in the West". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 193–224. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Islamic science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (Second ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–92. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The recovery and assimilation of Geek and Islamic science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 225–53. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Principe, Lawrence M. (2011). "Introduction". Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction (First ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-199-56741-6.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (1990). "Conceptions of the Scientific Revolution from Baker to Butterfield: A preliminary sketch". In David C. Lindberg; Robert S. Westman (eds.). Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution (First ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-521-34262-9.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The legacy of ancient and medieval science". The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 357–368. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Del Soldato, Eva (2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Grant, Edward (2007). "Transformation of medieval natural philosophy from the early period modern period to the end of the nineteenth century". A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (First ed.). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–322. ISBN 978-052-1-68957-1.

- ^ Cahan, David, ed. (2003). From Natural Philosophy to the Sciences: Writing the History of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08928-7.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary dates the origin of the word "scientist" to 1834.

- ^ a b Lightman, Bernard (2011). "13. Science and the Public". In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature : From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0226317830.

- ^ a b Bishop, Alan (1991). "Environmental activities and mathematical culture". Mathematical Enculturation: A Cultural Perspective on Mathematics Education. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 20–59. ISBN 978-0-792-31270-3.

- ^ a b Bunge, Mario (1998). "The Scientific Approach". Philosophy of Science: Volume 1, From Problem to Theory. Vol. 1 (revised ed.). New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN 978-0-765-80413-6.

- ^ a b Fetzer, James H. (2013). "Computer reliability and public policy: Limits of knowledge of computer-based systems". Computers and Cognition: Why Minds are not Machines (1st ed.). Newcastle, United Kingdom: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 271–308. ISBN 978-1-443-81946-6.

- ^ Fischer, M.R.; Fabry, G (2014). "Thinking and acting scientifically: Indispensable basis of medical education". GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung. 31 (2): Doc24. doi:10.3205/zma000916. PMC 4027809. PMID 24872859.

- ^ Abraham, Reem Rachel (2004). "Clinically oriented physiology teaching: strategy for developing critical-thinking skills in undergraduate medical students". Advances in Physiology Education. 28 (3): 102–04. doi:10.1152/advan.00001.2004. PMID 15319191.

- ^ Sinclair, Marius. "On the Differences between the Engineering and Scientific Methods". The International Journal of Engineering Education.

- ^ "Engineering Technology :: Engineering Technology :: Purdue School of Engineering and Technology, IUPUI". www.engr.iupui.edu. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ Grant, Edward (January 1, 1997). "History of Science: When Did Modern Science Begin?". The American Scholar. 66 (1): 105–113. JSTOR 41212592.

- ^ Pingree, David (December 1992). "Hellenophilia versus the History of Science". Isis. 4 (4): 554–63. Bibcode:1992Isis...83..554P. doi:10.1086/356288. JSTOR 234257.

- ^ Sima Qian (司馬遷, d. 86 BCE) in his Records of the Grand Historian (太史公書) covering some 2500 years of Chinese history, records Sunshu Ao (孫叔敖, fl. c. 630–595 BCE – Zhou dynasty), the first known hydraulic engineer of China, cited in (Joseph Needham et.al (1971) Science and Civilisation in China 4.3 p. 271) as having built a reservoir which has lasted to this day.