Semiprime

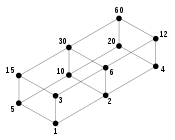

In mathematics, a semiprime (also called biprime or 2-almost prime, or pq number) is a natural number that is the product of two (not necessarily distinct) prime numbers. The semiprimes less than 100 are 4, 6, 9, 10, 14, 15, 21, 22, 25, 26, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 46, 49, 51, 55, 57, 58, 62, 65, 69, 74, 77, 82, 85, 86, 87, 91, 93, 94, and 95. (sequence A001358 in the OEIS). Semiprimes that are not perfect squares are called discrete, or distinct, semiprimes.

By definition, semiprime numbers have no composite factors other than themselves. For example, the number 26 is semiprime and its only factors are 1, 2, 13, and 26.

Properties

The total number of prime factors Ω(n) for a semiprime n is two, by definition. A semiprime is either a square of a prime or square-free. The square of any prime number is a semiprime, so the largest known semiprime will always be the square of the largest known prime, unless the factors of the semiprime are not known. It is conceivable, but unlikely, that a way could be found to prove a larger number is a semiprime without knowing the two factors.[1] A composite non-divisible by primes is semiprime. Various methods, such as elliptic pseudo-curves and the Goldwasser-Kilian ECPP theorem have been used to create provable, unfactored semiprimes with hundreds of digits.[2] These are considered novelties, since their construction method might prove vulnerable to factorization, and because it is simpler to multiply two primes together.

For a semiprime n = pq the value of Euler's totient function (the number of positive integers less than or equal to n that are relatively prime to n) is particularly simple when p and q are distinct:

- φ(n) = (p − 1) (q − 1) = p q − (p + q) + 1 = n − (p + q) + 1.

If otherwise p and q are the same,

- φ(n) = φ(p2) = (p − 1) p = p2 − p = n − p.

The concept of the prime zeta function can be adapted to semiprimes, which defines constants like

Applications

Semiprimes are highly useful in the area of cryptography and number theory, most notably in public key cryptography, where they are used by RSA and pseudorandom number generators such as Blum Blum Shub. These methods rely on the fact that finding two large primes and multiplying them together (resulting in a semiprime) is computationally simple, whereas finding the original factors appears to be difficult. In the RSA Factoring Challenge, RSA Security offered prizes for the factoring of specific large semiprimes and several prizes were awarded. The most recent such challenge closed in 2007.[3]

In practical cryptography, it is not sufficient to choose just any semiprime; a good number must evade a number of well-known special-purpose algorithms that can factor numbers of certain form. The factors p and q of n should both be very large, around the same order of magnitude as the square root of n; this makes trial division and Pollard's rho algorithm impractical. At the same time they should not be too close together, or else the number can be quickly factored by Fermat's factorization method. The number may also be chosen so that none of p − 1, p + 1, q − 1, or q + 1 are smooth numbers, protecting against Pollard's p − 1 algorithm or Williams' p + 1 algorithm. However, these checks cannot take future algorithms or secret algorithms into account, introducing the possibility that numbers in use today may be broken by special-purpose algorithms.

In 1974 the Arecibo message was sent with a radio signal aimed at a star cluster. It consisted of 1679 binary digits intended to be interpreted as a 23×73 bitmap image. The number 1679 = 23×73 was chosen because it is a semiprime and therefore can only be broken down into 23 rows and 73 columns, or 73 rows and 23 columns.

See also

References

- ^ Chris Caldwell, The Prime Glossary: semiprime at The Prime Pages. Retrieved on 2013-09-04.

- ^ Broadhurst, David (12 March 2005). "To prove that N is a semiprime". Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- ^ Information Security, Governance, Risk, and Compliance - EMC. RSA. Retrieved on 2014-05-11.

![{\displaystyle \leq {\sqrt[{3}]{n}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e041f1c4a4d3e728ff592ea93ae73e5761ecd7d9)