Sri Lankan leopard

| Sri Lankan Leopard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sri Lankan leopard | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. pardus

|

| Subspecies: | P. p. kotiya

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera pardus kotiya Deraniyagala, 1956

| |

| |

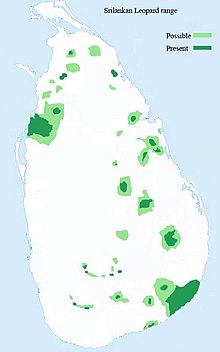

| Distribution of the Sri Lankan leopard | |

The Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya) is a leopard subspecies native to Sri Lanka. Classified as Endangered by IUCN, the population is believed to be declining due to numerous threats including poaching for trade and human-leopard conflicts. No subpopulation is larger than 250 individuals.[1]

The leopard is colloquially known as Kotiya (කොටියා) in Sinhala and Chiruththai (சிறுத்தை) in Tamil.[2] The Sri Lankan subspecies was first described in 1956 by the Sri Lankan zoologist Deraniyagala.[3]

Characteristics

The Sri Lankan leopard has a tawny or rusty yellow coat with dark spots and close-set rosettes, which are smaller than in Indian leopards. Seven females measured in the early 20th century averaged a weight of 64 lb (29 kg) and had a mean head-to-body-length of 3 ft 5 in (1.04 m) with a 2 ft 6.5 in (77.5 cm) long tail, the largest being 3 ft 9 in (1.14 m) with a 2 ft 9 in (84 cm) long tail; 11 males averaged 124 lb (56 kg), the largest being 170 lb (77 kg), and measured 4 ft 2 in (1.27 m) with a 2 ft 10 in (86 cm) long tail, the largest being 4 ft 8 in (1.42 m) with a 3 ft 2 in (97 cm) long tail.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Sri Lankan leopards have historically been found in all habitats throughout the island. These habitat types can be broadly categorized into:[4]

- arid zone with <1000 mm rainfall;

- dry zone with 1000–2000 mm rainfall;

- wet zone with >2000 mm rainfall.

Leopards have been observed in dry evergreen monsoon forest, arid scrub jungle, low and upper highland forest, rainforest, and wet zone intermediate forests.[citation needed]

In 2001 to 2002, adult resident leopard density was estimated at 17.9 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) in Block I of Yala National Park in Sri Lanka’s southeastern coastal arid zone. This block encompasses 140 km2 (54 sq mi), contains sizeable coastal plains and permanent man-made and natural waterholes, which combined allow for a very high density of prey species.[1]

The Wilpattu National Park is also known as a good place to watch leopards. Leopards tend to be more readily observed in parts of Sri Lanka than in other countries.[citation needed]

Ecology and behaviour

A study in Yala National Park indicates that Sri Lankan leopards are not any more social than other leopard subspecies. They are solitary hunters, with the exception of females with young. Both sexes live in overlapping territories with the ranges of males overlapping the smaller ranges of several females, as well as overlapping the ranges of neighbouring males. They prefer hunting at night, but are also active during dawn and dusk, and daytime hours. They rarely haul their kills into trees, which is likely due to the lack of competition and the relative abundance of prey. Since leopards are the apex predators they don't need to protect their prey.[5]

The Sri Lankan leopard is the country's top predator. Like most cats, it is pragmatic in its choice of diet which can include small mammals, birds, reptiles as well as larger animals. Axis or spotted deer make up the majority of its diet in the dry zone. The animal also preys on sambar, barking deer, wild boar and monkeys. The cat is known to tackle almost fully grown buffalos.[citation needed]

The Sri Lankan leopard hunts like other leopards, silently stalking its prey until it is within striking distance where it unleashes a burst of speed to quickly pursue and pounce on its victim. The prey is usually dispatched with a single bite to the throat.

There appears to be no birth season or peak, with births scattered across months.[5] A litter usually consists of 2 cubs.

Threats

The survival of the Sri Lankan leopard is threatened due to poaching for trade (primarily to India) and human-leopard conflict.[1]

Conservation

Further research into the Sri Lankan leopard is needed for any conservation measure to be effective. The Leopard Project under the Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust (WWCT) is working closely with the Government of Sri Lanka to ensure this occurs. The Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society will also undertake some studies. The WWCT is engaged in the central hills region where fragmentation of the leopard's habitat is rapidly occurring.[citation needed]

In captivity

As of December 2011, there are 75 captive Sri Lankan leopards in zoos worldwide. Within the European Endangered Species Programme 27 male, 29 female and 8 unsexed individuals are kept.[6]

The EEP breeding program is managed by Zoo Cerza, France.[citation needed]

Local names

Panthera pardus kotiya is the kotiyā proper.[7] Traditional Sinhala idioms, such as 'a change in the jungle (habitat) will not change the spots of a "kotiyā"', confirms the traditional use of "kotiyā" to refer to leopard, instead of tiger that has stripes.[citation needed]

But due to a nomenclature mishap that occurred in the late 1980s, "kotiyā" has now become the colloquial Sinhala term for tiger. Still "kotiya" is used to referred to leopard in the mainstream but at the same time "diviyā" (දිවියා) is used informally by many. The term "diviyā" refers to smaller wild cats such as "Handun Diviyā" or "Kola Diviyā". Both names are used interchangeably for the Fishing Cat and the Rusty-spotted cat.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the word 'kotiya' was being frequently incorrectly translated into English as "tiger" in Sri Lankan media due to incorrect information that was received from the then head of the Wildlife Department in Sri Lanka.[citation needed] He had allegedly said that "there are no kotiyas (tigers) in Sri Lanka but diviyās", misinterpreting Panthera pardus kotiya as "diviyā", the Sinhala term used for small wild cats. Although it is correct that there are no tigers in Sri Lanka, the formal Sinhala word for tiger is "viyagraya" and not "kotiyā".[citation needed]

A further complicating factor is that the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (Tamil Tigers) were colloquially known to the Sinhala-speaking community as 'Koti', the plural form of 'Kotiyā'.

References

- ^ a b c d Template:IUCN

- ^ a b Pocock, R.I. (1939) The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. Taylor and Francis, Ltd., London. Pp. 226–231.

- ^ Deraniyagala, P.E.P. (1956). The Ceylon leopard, a distinct subspecies. Spolia Zeylanica 28: 115–116.

- ^ Phillips, W. W. A. (1935). Manual of the mammals of Sri Lanka. Part III. Second revised edition, Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Colombo 1984.

- ^ a b Kittle, A., Watson, A. (2005) A short report on research of an arid zone leopard population (Panthera pardus kotiya), Ruhuna (Yala) National Park, Sri Lanka. The Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust, Sri Lanka.

- ^ International Species Information System (2011). "ISIS Species Holdings: Panthera pardus kotiya, December 2011".

- ^ "Panthera pardus kotiya". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

External links

- Species portrait Panthera pardus in Asia and short portrait P. pardus kotiya; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

- The Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust, Sri Lanka: The Leopard Project

- ARKive: Images and movies of the Sri Lankan leopard