Three Principles of the People

| Three Principles of the People | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

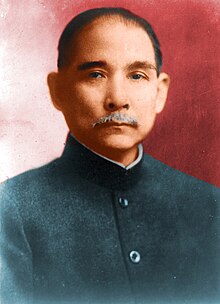

Sun Yat-sen, who developed the Three Principles of the People | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 三民主義 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 三民主义 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Template:Contains Chinese text

|

|---|

|

|

The Three Principles of the People, also translated as Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, or Tridemism[1] is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to make China a free, prosperous, and powerful nation. The three principles are often translated into and summarized as nationalism, democracy, and the livelihood of the people. He believed that the economic livelihood of the people depended on adopting the teachings of the American economist Henry George, writing that "The teachings of your single-taxer, Henry George, will be the basis of our program of reform."

Its influence and legacy of implementation is most apparent in the governmental organization of the Republic of China (ROC), which currently administers Taiwan, Penghu, Quemoy, and Matsu Islands. This philosophy has been claimed as the cornerstone of the Republic of China's policy as carried by the Kuomintang (KMT). The principles also appear in the first line of the National Anthem of the Republic of China.

Origins

In 1894 when the Revive China Society was formed, Sun only had two principles: nationalism and democracy. He did not pick up the third idea, welfare, until his three year trip to Europe (1896–1898).[2] He did not announce these ideas until spring of 1905 when he was in Europe again. Sun was in Brussels, and made the first speech of his life on the "Three Principles of the People".[3] In many cities he was able to organize the Revive China Society. There were about 30 members in the branch at the time in Brussels, 20 in Berlin, and 10 in Paris.[3] After the Tongmenghui was formed, Sun published an editorial in Min Bao (民報).[2] This was the first time the ideas were expressed. Later on, in the anniversary issue of Min Bao, his long speech of the Three Principles was printed, and the editors of the newspaper discussed the problem of people's livelihood.[2]

The ideology is said to be heavily influenced by Sun's experiences in the United States and contains elements of the American progressive movement and the thought championed by Abraham Lincoln. Sun credited a line from Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, "government of the people, by the people, for the people", as an inspiration for the Three Principles.[3] Dr. Sun's Three Principles of the People are inter-connected as the guideline for China's modernization development as stretched by Hu Hanmin.[4]

Enumeration

Mínzú

The Principle of Mínzú (民族主義, Mínzú Zhǔyì) is commonly rendered as "nationalism", literally "Populism" or "the People's rule/government", "Mínzú/People" clearly describing a nation rather than a group of persons united by a purpose, hence the commonly used and rather accurate translation "nationalism". By this, Sun meant independence from imperialist domination. To achieve this he believed that China must develop a "China-nationalism," Zhonghua Minzu, as opposed to an "ethnic-nationalism," so as to unite all of the different ethnicities of China, mainly composed by the five major groups of Han, Mongols, Tibetans, Manchus, and the Muslims (such as the Uyghurs), which together are symbolized by the Five Color Flag of the First Republic (1911–1928). This sense of nationalism is different from the idea of "ethnocentrism," which equates to the same meaning of nationalism in Chinese language. To achieve this he believed that China must develop a "national consciousness" so as to unite the Han in the face of imperialist aggression. He argued that "minzu", which can be translated as "people", "nationality" or "race", were defined by sharing common blood, livelihood, religion, language and customs.

Mínquán

The Principle of Mínquán (民權主義, Mínquán Zhǔyì) is usually translated as "democracy"; literally "the People's power" or "government by the People." To Sun, it represented a Western constitutional government. He divided political life of his ideal for China into two sets of 'powers': the power of politics and the power of governance.

The power of politics (政權, zhèngquán) are the powers of the people to express their political wishes, similar to those vested in the citizenry or the parliaments in other countries, and is represented by the National Assembly. There are four of these powers: election (選舉), recall (罷免), initiative (創制), and referendum (複決). These may be equated to "civil rights".

The power of governance (治權, zhìquán) are the powers of administration. Here he expanded the European-American constitutional theory of a three-branch government and a system of checks and balances by incorporating traditional Chinese administrative tradition to create a government of five branches (each of which is called a Yuan (院, yuàn, literally "court"). The Legislative Yuan, the Executive Yuan, and the Judicial Yuan came from Montesquieuan thought; the Control Yuan and the Examination Yuan came from Chinese tradition. (Note that the Legislative Yuan was first intended as a branch of governance, not strictly equivalent to a national parliament.)

Mínshēng

The Principle of Mínshēng (民生主義, Mínshēng Zhǔyì) is sometimes translated as "the People's welfare/livelihood," "Government for the People". The concept may be understood as social welfare and as a direct criticism of the inadequacies of both socialism and capitalism. Here he was influenced by the American thinker Henry George. Sun intended to introduce a Georgist tax reform.[5] The land value tax in Taiwan is a legacy thereof. Sun Yat-sen said that land value tax as "the only means of supporting the government is an infinitely just, reasonable, and equitably distributed tax, and on it we will found our new system."[6]

He divided livelihood into four areas: clothing, food, housing, and healthcare; and planned out how an ideal (Chinese) government can take care of these for its people. Sun died before he was able to fully explain his vision of this Principle and it has been the subject of much debate within both the Chinese Nationalist and Communist Parties, with the latter suggesting that Sun supported socialism. Dr. Sun transliterated Mínshēng in the Chinese context but did not address in full detail before he died. Chiang Kai-shek further elaborated the Mínshēng principle of both the importance of social well-being and recreational activities for a modernized China in 1953 in Taiwan.[7]

Canon

The most definite (canonical) exposition of these principles was a book compiled from notes of speeches that Sun gave near Guangzhou (taken by a colleague, Huang Changgu, in consultation with Sun), and therefore is open to interpretation by various parties and interest groups (see below) and may not have been as fully explicated as Sun might have wished. Indeed, Chiang Kai-shek supplied an annex to the Principle of Mínshēng, covering two additional areas of livelihood: education and leisure, and explicitly arguing that Mínshēng was not to be seen as supporting either communism or socialism. The French historian of Chinese history, Marie-Claire Bergère's view is that the book is a work of propaganda. Its purpose is to appeal to action rather than to thought. As Sun Yat-sen declared, a principle is not simply an idea; it is "a faith, a power."[8]

Legacy

The Three Principles of the People were claimed as the basis for the ideologies of the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek, of the Communist Party of China under Mao Zedong, and of the Reorganized National Government of China under Wang Jingwei. The Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China largely agreed on the meaning of nationalism but differed sharply on the meaning of democracy and people's welfare, which the former saw in Western social democratic terms and the latter interpreted in Marxist and communist terms. The Japanese collaborationist government interpreted nationalism less in terms of anti-imperialism and more in terms of cooperating with Japan to advance pan-Asian, but in practice, typically Japanese interests.

Taiwan

There were several higher-education institutes (university departments/faculties and graduate institutes) in Taiwan that used to devote themselves to the 'research and development' of the Three Principles in this aspect. Since the late 1990s, these institutes have re-oriented themselves so that other political theories are also admitted as worthy of consideration, and have changed their names to be more ideologically neutral (such as Democratic Studies Institute).

In addition to this institutional phenomenon, many streets and businesses in Taiwan are named "Sān-mín" or for one of the three principles. In contrast to other politically-derived street names, there has been no major renaming of these streets or institutions in the 1990s.

Although the term "Sanmin Zhuyi" (三民主義) has been less explicitly invoked since the mid-1980s, no major political party has explicitly attacked its principles. The Three Principles of the People remains explicitly part of the platform of the Kuomintang and in the Constitution of the Republic of China.

As for Taiwan independence supporters, some have objections regarding the formal constitutional commitment to a particular set of political principles. Also, they have been against the mandatory indoctrination in schools and universities, which have now been abolished in a piecemeal fashion beginning in the late 1990s. However, there is little fundamental hostility to the substantive principles themselves. In these circles, attitudes toward the Three Principles of the People span the spectrum from indifference to reinterpreting the Three Principles of the People in a local Taiwanese context rather than in a pan-Chinese one.

Vietnam

The Vietnam Revolutionary League was a union of various Vietnamese nationalist groups, run by the pro-Chinese Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng. The Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng translates directly into Vietnamese Kuomintang, and it was based on the Chinese Kuomintang party. Its stated goal was for unity with China under the Three Principles of the People, and opposition to Japanese and French Imperialists.[9][10] The Revolutionary League was controlled by Nguyễn Hải Thần, who was born in China and could not speak Vietnamese [citation needed] . General Zhang Fakui shrewdly blocked the Communists of Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh from entering the league, as his main goal was Chinese influence in Indo China.[11] The KMT utilized these Vietnamese nationalists during World War II against Japanese forces.[12]

Tibet

The pro-Kuomintang and pro-ROC Khamba revolutionary leader Pandatsang Rapga, who established the Tibet Improvement Party, adopted Dr. Sun's ideology including the Three Principles, incorporating them into his party and using Sun's doctrine as a model for his vision of Tibet after achieving his goal of overthrowing the Tibetan government.

Pandatsang Rapga hailed the Three Principles of Dr. Sun for helping Asian peoples against foreign imperialism and called for the feudal system to be overthrown. Rapga stated that "The Sanmin Zhuyi was intended for all peoples under the domination of foreigners, for all those who had been deprived of the rights of man. But it was conceived especially for the Asians. It is for this reason that I translated it. At that time, a lot of new ideas were spreading in Tibet", during an interview in 1975 by Dr. Heather Stoddard.[13] Dr. Sun's ideology was put into a Tibetan translation by Rapga.[14]

He believed that change in Tibet would only be possible in a manner similar to when the Qing Dynasty was overthrown in China. He borrowed the theories and ideas of the Kuomintang as the basis for his model for Tibet. The party was funded by the Kuomintang[15] and by the Pandatsang family.

Singapore

The establishment of the People's Power Party in May 2015 by opposition politician Goh Meng Seng marks the first time in contemporary Singaporean politics that a political party was formed with the Three Principles of the People and its system of having five branches of government as espoused by Dr Sun Yat-Sen as its official guiding ideology.[16]

The People's Power Party has adapted the ideas with a slight modification to the concepts of the Five Powers in order to stay relevance to modern contemporary political and social structures. The emphasis is put on the separation of the Five Powers which naturally means the separation of certain institutions from the Executive's control.

The Power of Impeachment (originally under Control Yuan) has been expanded to include various contemporary functional government institutions. Examples: Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, advocacy of Ombudsman Commission, Equal Opportunity Commission, Free Press and Freedom of Expression.

The Power of Examination has been adapted and modified to modern concept of Selection for both political leaders as well as civil servants. This involves institutions like Elections Department and Public Service Commission.

People's Power Party advocates that the institutions included in these two powers, namely Power of Impeachment and Power of Selection, to be put under the supervision of Singapore's Elected President.[17]

See also

- National Revolutionary Army

- Whampoa Military Academy

- History of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Pancasila (politics)

Bibliography

- Sun Yat-sen, translated by Pasquale d'Elia.The Triple Demism of Sun Yat-Sen. New York: AMS Press, Inc., 1974.

References

- ^ Stéphane Corcuff (editor) Memories of the Future: National Identity Issues and the Search for a New Taiwan. ISBN 0765607921

- ^ a b c Li Chien-Nung, translated by Teng, Ssu-yu, Jeremy Ingalls. The political history of China, 1840–1928. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand, 1956; rpr. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0602-6, ISBN 978-0-8047-0602-5. pp. 203–206.

- ^ a b c Sharman, Lyon (1968). Sun Yat-sen: His life and its meaning, a critical biography. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 94, 271.

- ^ "+{中華百科全書‧典藏版}+". ap6.pccu.edu.tw. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ^ Trescott, Paul B. (2007). Jingji Xue: The History of the Introduction of Western Economic Ideas Into China, 1850-1950. Chinese University Press. pp. 46–48.

'The teachings of your single-taxer, Henry George, will be the basis of our program of reform.'

- ^ Post, Louis Freeland (April 12, 1912). "Sun Yat Sen's Economic Program for China". The Public. 15: 349. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "〔民生主義育樂兩篇補述〕". terms.naer.edu.tw. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ^ Bergère, Marie-Claire (translated by Janet Lloyd) (1994). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 353. ISBN 0-8047-3170-5.

- ^ James P. Harrison (1989). The endless war: Vietnam's struggle for independence. Columbia University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-231-06909-X. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ United States. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Historical Division (1982). The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: History of the Indochina incident, 1940-1954. Michael Glazier. p. 56. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ Oscar Chapuis (2000). The last emperors of Vietnam: from Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 0-313-31170-6. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ William J. Duiker (1976). The rise of nationalism in Vietnam, 1900-1941. Cornell University Press. p. 272. ISBN 0-8014-0951-9. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ Gray Tuttle (2007). Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 152. ISBN 0-231-13447-9. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein (1991). A history of modern Tibet, 1913-1951: the demise of the Lamaist state. Vol. Volume 1 of A History of Modern Tibet (reprint, illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 450. ISBN 0-520-07590-0. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Vol. Volume 67 of Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 95. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ ["http://www.tremeritus.com/2015/05/19/goh-submits-application-to-set-up-peoples-power-party/" "http://www.tremeritus.com/2015/05/19/goh-submits-application-to-set-up-peoples-power-party/"]

{{citation}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "People's Power Party - PPP". facebook.com. Retrieved 2015-12-24.