Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

BryanLopez0 (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Large collection of poems by Rumi}} |

{{short description|Large collection of poems by Rumi}} |

||

{{italic title}} |

{{italic title}} |

||

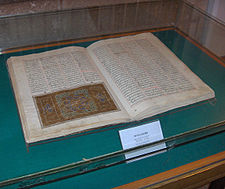

[[File: |

[[File:Shams_ud-Din_Tabriz_1502-1504_BNF_Paris.jpg|right|thumb|301x301px|A page of a copy circa 1503 of the ''Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi''. For details, see: [[Rumi ghazal 163]].]] |

||

{{Sufism}}'''''Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi''''' ''(The Works of Shams of Tabriz)'' ({{Lang-fa|دیوان شمس تبریزی}}) is a collection of poems written by the [[Persians|Persian]] poet and [[Sufism|Sufi]] mystic [[Mawlānā Jalāl-ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī]], also known as Rumi. A compilation of [[Lyric poetry|lyric]] poems written in the [[Persian language]], it contains more than 40,000 [[Verse (poetry)|verses]]<ref>Foruzanfar, 1957</ref> and over 3,000 [[ghazal]]s.<ref>Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 183</ref> While following the long tradition of [[Sufi poetry]] as well as the traditional metrical conventions of ghazals, the poems in the Divan showcase Rumi’s unique, trance-like poetic style.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 704</ref> Written in the aftermath of the disappearance of Rumi’s beloved spiritual teacher, [[Shams-i Tabrizi]], the Divan is dedicated to Shams and contains many verses praising him and lamenting his disappearance.<ref>Gooch, 2017, pp. 133-134</ref> Although not a didactic work, the Divan still explores deep philosophical themes, particularly those of love and longing.<ref>De Groot, 2011, p. 67</ref> |

|||

{{Sufism}} |

|||

'''''Dīvān-e Kabīr''''' or '''''Dīvān-e Šams-e Tabrīzī''''' ''(The Works of Šams Tabrīzī)'' ({{Lang-fa|دیوان شمس تبریزی}}) or '''''Dīvān-e Šams''''' is one of [[Mawlānā Jalāl-ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī]]'s (Rumi) masterpieces. A collection of lyric poems that contains more than 40,000 verses, it is written in the [[Persian language]] and is considered one of the greatest works of [[Persian literature]]. |

|||

== Content == |

|||

''Dīvān-e Kabīr'' ("the great divan") contains poems in several different styles of Eastern-Islamic poetry (e.g. odes, eulogies, quatrains, etc.). It contains 44,282 lines (according to [[Badiozzaman Forouzanfar|Foruzanfar]]'s edition,<ref>Furuzanfar, Badi-uz-zaman. ''Kulliyat-e Shams'', 8 vols., Tehran: Amir Kabir Press, 1957–66. Critical edition of the collected odes, quatrains and other poems of Rumi with glossary and notes.</ref> which is based on the oldest manuscripts available): 3,229 odes, or [[ghazal]]s (total lines = 34,662); 44 tarji-bands (total lines = 1698); and 1,983 [[Rubaʿi|quatrains]] (total lines = 7932).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/about_divan.html|title=About the Divan|work=dar-al-masnavi.org|accessdate=24 December 2016}}</ref> Although most of the poems are in New Persian, there are also some in [[Arabic language|Arabic]], and a small number of mixed Persian/Greek and Persian/Turkish poems. ''Dīvān-e Šams-e Tabrīzī'' is named in honour of Rumi's spiritual teacher and friend [[Shams Tabrizi]]. |

|||

The Divan contains poems in several different Eastern-Islamic poetic styles (e.g. ghazals, [[Elegy|elegies]], [[quatrains]], etc.). It contains 44,292 lines (according to Foruzanfar's edition,<ref>Foruzanfar, 1957</ref> which is based on the oldest manuscripts available); 3,229 ghazals in fifty-five different [[metres]] (34,662);<ref>Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 183</ref> 44 tarji-bands (1,698 lines); and 1,983 quatrains (7,932 lines).<ref>Gamard</ref> Although most of the poems are written in Persian, there are also some in [[Arabic]], as well as some bilingual poems written in [[Turkish language|Turkish]], [[Arabic]], and [[Greek language|Greek]].<ref>Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 182</ref> |

|||

== |

== Form and Style == |

||

Most of the poems in the Divan follow the form of a ghazal, a type of lyric poem often used to express themes of love and friendship as well as more mystical Sufi theological subjects.<ref>Boostani & Moghaddas, 2015, p. 77</ref> By convention, poets writing ghazals often adopted poetic personas which they then invoked as [[nom de plume|''noms de plume'']] at the end of their poems, in what are called ''takhallos''.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 435</ref> Rumi signed off most of his own ghazals as either ''Khâmush'' (Silence) or Shams-i Tabrizi.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 436</ref> |

|||

The following poem of Rumi is written in Persian while the last words of each verse end with a Greek word:<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://parsianjoman.org/?p=6002|title=واژههای یونانی در غزلهای مولانا|date=۱۳۹۷-۱-۱۹ ۲۱:۱۷:۳۰ +۰۰:۰۰|work=پارسیانجمن|access-date=2018-11-12|language=fa-IR}}</ref> |

|||

Though belonging to the long tradition of Sufi poetry, Rumi developed his own unique style. Notably, due to the extemporaneous manner in which Rumi composed his poems, much of Rumi’s poetry has an ecstatic, almost trance-like style that differs from the works of other professional Islamic poets.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 704</ref> Rumi evidently found the traditional metrical constraints of ghazals to be constraining, lamenting in one ghazal that fitting his poems into the traditional “dum-ta-ta-dum” ghazal metre was a process so dreadful that it killed him.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 705</ref> |

|||

# νηστικός / {{lang|fa|rtl=yes|نیم شب از عشق تا دانی چه میگوید خروس: خیز شب را زنده دار و روز روشن نستکوس}} |

|||

# ἄνεμος/ {{lang|fa|rtl=yes|پرها بر هم زند یعنی دریغا خواجهام : روزگار نازنین را میدهد بر آنموس}} |

|||

# ἄνθρωπος/ {{lang|fa|rtl=yes|در خروش است آن خروس و تو همی در خواب خوش : نام او را طیر خوانی نام خود را آنثروپوس}} |

|||

# ἄγγελος/ {{lang|fa|rtl=yes|آن خروسی که تو را دعوت کند سوی خدا: او به صورت مرغ باشد در حقیقات انگلوس}} |

|||

# βασιλιάς/ {{lang|fa|rtl=yes|من غلام آن خروس ام که او چنین پندی دهد : خاک پای او بِ آید از سر واسیلیوس}} |

|||

# καλόγερος/ {{lang|fa|rtl=yes|گَردِ کفشِ خاکِ پای مصطفی را سرمه ساز : تا نباشی روز حشر از جملهی کالویروس}} |

|||

# Σαρακηνός/ {{lang|fa|rtl=yes|رو شریعت را گزین و امر حق را پاس دار : گر عرب باشی و اگر ترک و اگر سراکنوس}} |

|||

== Origins & History == |

|||

The following are Greek verses in the poetry of Mawlana Jalal ad-Din Rumi (1207-1273), and his son, [[Sultan Walad]] (1226-1312). The works have been difficult to edit, because of the absence of vowel pointing in most of the verses, and the confusion of scribes unfamiliar with Greek; different editions of the verses vary greatly:<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.opoudjis.net/Play/rumiwalad.html|title=Untitled Document|website=www.opoudjis.net|access-date=2018-11-12}}</ref> |

|||

In 1244 C.E, Rumi, then a [[Islamic jurist|jurist]] and spiritual counselor working at the behest of the [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuk]] Sultan of [[Sultanate of Rum|Rûm]],<ref>Gooch, 2017, p. 81</ref> met a wandering Sufi [[dervish]] named Shams-i Tabrizi in [[Konya]].<ref> Gooch, 2017, p. 84</ref> Rumi, who previously had no background in poetics,<ref>Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 176</ref> quickly became attached to Shams, who acted as a spiritual teacher to Rumi and introduced him to music, sung poetry, and dance through Sufi [[Sama (Sufism)|''samas'']].<ref>Gooch, 2017, p. 91</ref> Shams abruptly left Konya in 1246 C.E,<ref>Gooch, 2017, p. 125</ref> returned a year later,<ref>Gooch, 2017, p. 131</ref> then vanished again in 1248 C.E,<ref>Gooch, 2017, pp. 145-146</ref> possibly having been murdered.<ref>Gooch, 2017, p. 149</ref> During Sham’s initial separation from Rumi, Rumi wrote poetic letters to Shams pleading for his return.<ref>Gooch, 2107, p. 111</ref> Following Sham’s second disappearance, Rumi returned to writing poetry lauding Shams and lamenting his disappearance.<ref>Gooch, 2017, pp. 133-134</ref> These poems would be collected after Rumi’s death by his students as the ''Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi''.<ref>Gooch, 2017, p. 141</ref> |

|||

The creation dates of some of the poems in the Divan are unknown.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 277</ref> However, a major portion of the Divan’s poems were written in the initial aftermath of Sham’s second disappearance.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 277</ref> Therefore, most of the poems probably date from around 1247 C.E. and the years that followed until Rumi had overcome his grief over the loss of Shams.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 277</ref> Another seventy poems in the Divan were written after Rumi had confirmed that Shams was dead.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 277</ref> Rumi dedicated these poems to his friend Salah al-Din Zarkub, who passed away in December, 1258.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 277</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+Greek verses in the poetry of Rumi |

|||

!Verse |

|||

!Greek Phrases (written in the Persian script by Rumi) |

|||

!Greek |

|||

equivalent |

|||

!Persian Translation |

|||

!English Translation |

|||

|- |

|||

|1a |

|||

|افندیس مَس ان، کی آگاپومن تُن/دُن |

|||

|Αφέντης μας έν κι αγαπούμεν τον |

|||

|او سرور ما است و ما او را دوست داریم) عاشق او ایم) |

|||

|He is our Master and we love him |

|||

|- |

|||

|1b |

|||

|کی اپ اکِینون اِن کالی زوی مَس |

|||

|κι απ’ εκείνον έν καλή η ζωή μας |

|||

|به خاطر او است که زندگی ما خوش است |

|||

|It is because of him that life is sweet |

|||

|- |

|||

|2a |

|||

|ییَتی ییریسِس، ییَتی ورومیسِس |

|||

|γιατί γύρισες γιατί βρώμισες |

|||

|چرا برگشتی؟ چرا بیمار ای؟ |

|||

|Why did you turn around because you were ill? |

|||

|- |

|||

|2b |

|||

|په مه تی اپاتِس، په مه تی اخاسِس |

|||

|πε με τι έπαθες, πε με τι έχασες! |

|||

|به من بگو ترا چه افتاد؟ به من بگو چه گم کردهای؟ |

|||

|Tell me what happened to you? Tell me what did you loose? |

|||

|- |

|||

|11a |

|||

|ایلا کالی مو! ایلا شاهی مو! |

|||

|Έλα καλέ μου, έλα σάχη μου· |

|||

|بیا زیبای من. بیا شاه من |

|||

|Come my beautiful, come my king. |

|||

|- |

|||

|11b |

|||

|ایلا کالی مو! ایلا شاهی مو! |

|||

|χαρά δε δίδεις, δος μας άνεμο! |

|||

|[اگر] شادی نمیدهی، به ما رایحهای بده. |

|||

|If you do not give us joy, give us "wind"/"breath"! |

|||

|- |

|||

|12a |

|||

|پو دیپسا پینِی، پو پونِی لَلِی |

|||

|Που διψά πίνει, που πονεί λαλεί· |

|||

|آن که تشنه است مینوشد، آن که خسته [=زخمی] است میگرید |

|||

|The thirsty one drinks while the wounded one flees |

|||

|- |

|||

|12b |

|||

|میدِن چاکوسِس، کاله، تو ییالی |

|||

|μηδέν τσάκωσες, καλέ, το γυαλί |

|||

|ای زیبا، آیا تو جام را شکستهای؟ |

|||

|Tell me beautiful, did you break the cup? |

|||

|} |

|||

[[File:Turkey.Konya019.jpg|thumb|left|225px|<center>Dīvān-e Kabīr (''Divan-ı Kebir'') from 1366 <br /> Mevlâna mausoleum, Konya, Turkey</center>]] |

|||

By the sixteenth century, most editors organized the poems in the Divan by alphabetical order according to the last letter of each line, disregarding the varying meters and topics of the poems.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 394</ref> This method for arranging lyrical poems in the Divan is still used in modern Iranian editions of the Divan.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 395</ref> Turkish editions, however, follow the practice of the [[Mevlevi Order]] and group the poems by metre.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 395</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

The first printed copy of the Divan was made in [[Europe]] in 1838 by [[:de:Vinzenz Rosenzweig von Schwannau|Vincenz von Rosenzweig-Schwannau]], who printed seventy-five poems of dubious authenticity.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 400</ref> [[Reynold A. Nicholson]] produced a more selective text of fifty ghazals from the Divan, although [[Badiozzaman Forouzanfar|Badi al-Zaman Foruzanfar’s]] critical edition has since determined several of Nicholson’s selections to have been inauthentic.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 400</ref> In 1957, Foruzanfar published a critical collection of the Divan’s poems based upon manuscripts written within a hundred years of Rumi’s death.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 402</ref> |

|||

== Themes == |

|||

Although the Divan is, in contrast to Rumi's [[Masnavi]], not a didactic work, it is still a deeply philosophical work, expressing Rumi’s mystical Sufi theology. Among the more prominent themes in the Divan are those of love and longing. Some Rumi scholars such as [[:nl:Rokus de Groot|Rokus de Groot]] argue that Rumi rejects longing in favour of a divine unity, or ''[[tawhid]]'', a concept which de Groot considers to originate in the ''[[Shahada|Shahada]]'s'' declaration that there is no other god save God.<ref>De Groot, 2011, p. 67</ref> According to de Groot, Rumi holds that longing, being a lust to grasp something beyond oneself, necessarily creates a duality between subjects and objects.<ref>De Groot, 2011, p. 64</ref> Thus, those drunk with love, as Rumi writes, are double, whereas those drunk with god are united as one.<ref>Rumi (tran. Nicholson), 1973, p. 47</ref> De Groot maintains that Rumi’s philosophy of the oneness of love explains why Rumi signed about a third of the Divan under Shams-i Tabrizi’s name; By writing as if he and Shams were the same person, Rumi repudiated the longing that plagued him after Shams’ disappearance in favour of the unity of all beings found in divine love.<ref>De Groot, 2011, p. 83</ref> |

|||

In contrast, Mostafa Vaziri argues for a non-Islamic interpretation of Rumi. In Vaziri’s view, Rumi’s references to love compose a separate ''Mazhab-e ‘Ishq'', or “Religion of Love,” which was universalist rather than uniquely Islamic in outlook.<ref>Vaziri, 2015, pp.12-13</ref> Vaziri posits that Rumi’s notion of love was a designation for the incorporeal reality of existence that lies outside of physical conception.<ref>Vaziri, 2015, pp.13</ref> Thus, according to Vaziri, Rumi’s references to Shams in the Divan refer not to the person of Shams but to the all-encompassing universality of the love-reality.<ref>Vaziri, 2015, pp. 14</ref> |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||

The Divan has influenced several poets and writers. American [[Transcendentalism|Transcendentalists]] such as [[Ralph Waldo Emerson]] and [[Walt Whitman]] were acquainted with the Divan, and were inspired by its philosophical mysticism.<ref>Boostani & Moghaddas, 2015, pp. 79-80</ref> Many late [[Victorian era|Victorian]] and [[Georgian Poetry|Georgian]] poets in England were also acquainted with Rumi from Nicholson’s translation of the Divan.<ref>Lewis, 2014, p. 728</ref> Prominent Rumi interpreter [[Coleman Barks]] has used selections from Nevit Ergin’s translation of the Divan in his own reinterpretations of Rumi,<ref>Merwin, 2002</ref> albeit with controversy as to the accuracy and authenticity of Barks’ interpretation.<ref>Ali, 2017</ref> |

|||

[[File:Turkey.Konya019.jpg|left|thumb|225x225px|<center>Pages from a 1366 manuscript of the Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi in the Mevlâna mausoleum, Konya, Turkey</center>]] |

|||

== References == |

|||

===Citations=== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

== |

===Bibliography=== |

||

{{refbegin|30em|indent=yes}} |

|||

* [http://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/about-foruz.html About Foruzanfar and his Edition of Rumi's Divan] |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last1=Boostani|first1= Mahdieh|last2=Moghaddas|first2=Bahram|title=The Influence of Rumi's Thought on Whitman's Poetry|journal=Research Result: Theoretical and Applied Linguistics|date=2015 |volume=1 |issue=3 |pages=73–82 |url=http://rrlinguistics.ru/en/journal/issue/3-5-2015/}} |

|||

* {{cite news |last=Ali |first=Rozina |date=2017 |title=The Erasure of Islam from the Poetry of Rumi|url=https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-erasure-of-islam-from-the-poetry-of-rumi |work=The New Yorker}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=De Groot|first= Rokus|title=Rumi and the Abyss of Longing|journal=Mawlana Rumi Review|date=2011 |volume=2 |issue=1 |pages=61-93|jstor=45236317 |doi=10.2307/45236317}} |

|||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/about_divan.html |title=About the Divan |last=Gamard |first=Ibrahim |publisher=Electronic School of Masnavi Studies}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Gooch |first=Brad |title=Rumi's Secret: The Life of the Sufi Poet of Love |location=New York |publisher=HarperCollins |year=2017 |isbn=978-0-0619-9914-7}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Lewis|first=Franklin D.|title=Rumi - Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi |location=New York |publisher=OneWorld Publications |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-7807-4737-8}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Foruzanfar|first=Badi-uz-zaman|title=Kulliyat-e Shams|location=Tehran |publisher=Amir Kabir Press |year=1957 |quote=Critical edition of the collected odes, quatrains and other poems of Rumi with glossary and notes.}} |

|||

* {{cite news |last=Merwin |first=W.S.|date=2002 |title=Echoes of Rumi|url=https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2002/06/13/echoes-of-rumi/|work=The New York Review of Books}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Rumi|first=Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad|translator-last=Nicholson|translator-first=Reynold A.|title=Divani Shamsi Tabriz|location=San Fransisco|publisher=The Rainbow Bridge |year=1973}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Foruzanfar|first=Badi-uz-zaman|translator-last=Sorkhabi|translator-first=Rasoul|title=Some Remarks on Rumi's Poetry|journal=Mawlana Rumi Review|date=2012 |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=173-186|jstor=45236338 |doi=10.2307/45236338}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Vaziri|first=Mostafa|title=Rumi and Shams’ Silent Rebellion|location=New York|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |year=2015|isbn=978-1-137-53080-6}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{Rumi}} |

|||

{{Persian literature}} |

|||

* [http://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/about_divan.html About Rumi's Divan from the Electronic School of Masnavi Studies] |

|||

{{Rumi}}{{Persian literature}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Divan-E Shams-E Tabrizi}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Divan-E Shams-E Tabrizi}} |

||

| Line 94: | Line 61: | ||

[[Category:Iranian books]] |

[[Category:Iranian books]] |

||

[[Category:Ancient Persian mystical literature]] |

[[Category:Ancient Persian mystical literature]] |

||

{{Iran-culture-stub}} |

{{Iran-culture-stub}} |

||

{{Poetry-collection-stub}} |

{{Poetry-collection-stub}} |

||

Revision as of 17:32, 9 December 2020

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi (The Works of Shams of Tabriz) (Persian: دیوان شمس تبریزی) is a collection of poems written by the Persian poet and Sufi mystic Mawlānā Jalāl-ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī, also known as Rumi. A compilation of lyric poems written in the Persian language, it contains more than 40,000 verses[1] and over 3,000 ghazals.[2] While following the long tradition of Sufi poetry as well as the traditional metrical conventions of ghazals, the poems in the Divan showcase Rumi’s unique, trance-like poetic style.[3] Written in the aftermath of the disappearance of Rumi’s beloved spiritual teacher, Shams-i Tabrizi, the Divan is dedicated to Shams and contains many verses praising him and lamenting his disappearance.[4] Although not a didactic work, the Divan still explores deep philosophical themes, particularly those of love and longing.[5]

Content

The Divan contains poems in several different Eastern-Islamic poetic styles (e.g. ghazals, elegies, quatrains, etc.). It contains 44,292 lines (according to Foruzanfar's edition,[6] which is based on the oldest manuscripts available); 3,229 ghazals in fifty-five different metres (34,662);[7] 44 tarji-bands (1,698 lines); and 1,983 quatrains (7,932 lines).[8] Although most of the poems are written in Persian, there are also some in Arabic, as well as some bilingual poems written in Turkish, Arabic, and Greek.[9]

Form and Style

Most of the poems in the Divan follow the form of a ghazal, a type of lyric poem often used to express themes of love and friendship as well as more mystical Sufi theological subjects.[10] By convention, poets writing ghazals often adopted poetic personas which they then invoked as noms de plume at the end of their poems, in what are called takhallos.[11] Rumi signed off most of his own ghazals as either Khâmush (Silence) or Shams-i Tabrizi.[12]

Though belonging to the long tradition of Sufi poetry, Rumi developed his own unique style. Notably, due to the extemporaneous manner in which Rumi composed his poems, much of Rumi’s poetry has an ecstatic, almost trance-like style that differs from the works of other professional Islamic poets.[13] Rumi evidently found the traditional metrical constraints of ghazals to be constraining, lamenting in one ghazal that fitting his poems into the traditional “dum-ta-ta-dum” ghazal metre was a process so dreadful that it killed him.[14]

Origins & History

In 1244 C.E, Rumi, then a jurist and spiritual counselor working at the behest of the Seljuk Sultan of Rûm,[15] met a wandering Sufi dervish named Shams-i Tabrizi in Konya.[16] Rumi, who previously had no background in poetics,[17] quickly became attached to Shams, who acted as a spiritual teacher to Rumi and introduced him to music, sung poetry, and dance through Sufi samas.[18] Shams abruptly left Konya in 1246 C.E,[19] returned a year later,[20] then vanished again in 1248 C.E,[21] possibly having been murdered.[22] During Sham’s initial separation from Rumi, Rumi wrote poetic letters to Shams pleading for his return.[23] Following Sham’s second disappearance, Rumi returned to writing poetry lauding Shams and lamenting his disappearance.[24] These poems would be collected after Rumi’s death by his students as the Divan-i Shams-i Tabrizi.[25]

The creation dates of some of the poems in the Divan are unknown.[26] However, a major portion of the Divan’s poems were written in the initial aftermath of Sham’s second disappearance.[27] Therefore, most of the poems probably date from around 1247 C.E. and the years that followed until Rumi had overcome his grief over the loss of Shams.[28] Another seventy poems in the Divan were written after Rumi had confirmed that Shams was dead.[29] Rumi dedicated these poems to his friend Salah al-Din Zarkub, who passed away in December, 1258.[30]

By the sixteenth century, most editors organized the poems in the Divan by alphabetical order according to the last letter of each line, disregarding the varying meters and topics of the poems.[31] This method for arranging lyrical poems in the Divan is still used in modern Iranian editions of the Divan.[32] Turkish editions, however, follow the practice of the Mevlevi Order and group the poems by metre.[33]

The first printed copy of the Divan was made in Europe in 1838 by Vincenz von Rosenzweig-Schwannau, who printed seventy-five poems of dubious authenticity.[34] Reynold A. Nicholson produced a more selective text of fifty ghazals from the Divan, although Badi al-Zaman Foruzanfar’s critical edition has since determined several of Nicholson’s selections to have been inauthentic.[35] In 1957, Foruzanfar published a critical collection of the Divan’s poems based upon manuscripts written within a hundred years of Rumi’s death.[36]

Themes

Although the Divan is, in contrast to Rumi's Masnavi, not a didactic work, it is still a deeply philosophical work, expressing Rumi’s mystical Sufi theology. Among the more prominent themes in the Divan are those of love and longing. Some Rumi scholars such as Rokus de Groot argue that Rumi rejects longing in favour of a divine unity, or tawhid, a concept which de Groot considers to originate in the Shahada's declaration that there is no other god save God.[37] According to de Groot, Rumi holds that longing, being a lust to grasp something beyond oneself, necessarily creates a duality between subjects and objects.[38] Thus, those drunk with love, as Rumi writes, are double, whereas those drunk with god are united as one.[39] De Groot maintains that Rumi’s philosophy of the oneness of love explains why Rumi signed about a third of the Divan under Shams-i Tabrizi’s name; By writing as if he and Shams were the same person, Rumi repudiated the longing that plagued him after Shams’ disappearance in favour of the unity of all beings found in divine love.[40]

In contrast, Mostafa Vaziri argues for a non-Islamic interpretation of Rumi. In Vaziri’s view, Rumi’s references to love compose a separate Mazhab-e ‘Ishq, or “Religion of Love,” which was universalist rather than uniquely Islamic in outlook.[41] Vaziri posits that Rumi’s notion of love was a designation for the incorporeal reality of existence that lies outside of physical conception.[42] Thus, according to Vaziri, Rumi’s references to Shams in the Divan refer not to the person of Shams but to the all-encompassing universality of the love-reality.[43]

Legacy

The Divan has influenced several poets and writers. American Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman were acquainted with the Divan, and were inspired by its philosophical mysticism.[44] Many late Victorian and Georgian poets in England were also acquainted with Rumi from Nicholson’s translation of the Divan.[45] Prominent Rumi interpreter Coleman Barks has used selections from Nevit Ergin’s translation of the Divan in his own reinterpretations of Rumi,[46] albeit with controversy as to the accuracy and authenticity of Barks’ interpretation.[47]

References

Citations

- ^ Foruzanfar, 1957

- ^ Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 183

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 704

- ^ Gooch, 2017, pp. 133-134

- ^ De Groot, 2011, p. 67

- ^ Foruzanfar, 1957

- ^ Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 183

- ^ Gamard

- ^ Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 182

- ^ Boostani & Moghaddas, 2015, p. 77

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 435

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 436

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 704

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 705

- ^ Gooch, 2017, p. 81

- ^ Gooch, 2017, p. 84

- ^ Foruzanfar (tran. Sorkhabi), 2012, p. 176

- ^ Gooch, 2017, p. 91

- ^ Gooch, 2017, p. 125

- ^ Gooch, 2017, p. 131

- ^ Gooch, 2017, pp. 145-146

- ^ Gooch, 2017, p. 149

- ^ Gooch, 2107, p. 111

- ^ Gooch, 2017, pp. 133-134

- ^ Gooch, 2017, p. 141

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 277

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 277

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 277

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 277

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 277

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 394

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 395

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 395

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 400

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 400

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 402

- ^ De Groot, 2011, p. 67

- ^ De Groot, 2011, p. 64

- ^ Rumi (tran. Nicholson), 1973, p. 47

- ^ De Groot, 2011, p. 83

- ^ Vaziri, 2015, pp.12-13

- ^ Vaziri, 2015, pp.13

- ^ Vaziri, 2015, pp. 14

- ^ Boostani & Moghaddas, 2015, pp. 79-80

- ^ Lewis, 2014, p. 728

- ^ Merwin, 2002

- ^ Ali, 2017

Bibliography

- Boostani, Mahdieh; Moghaddas, Bahram (2015). "The Influence of Rumi's Thought on Whitman's Poetry". Research Result: Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. 1 (3): 73–82.

- Ali, Rozina (2017). "The Erasure of Islam from the Poetry of Rumi". The New Yorker.

- De Groot, Rokus (2011). "Rumi and the Abyss of Longing". Mawlana Rumi Review. 2 (1): 61–93. doi:10.2307/45236317. JSTOR 45236317.

- Gamard, Ibrahim. "About the Divan". Electronic School of Masnavi Studies.

- Gooch, Brad (2017). Rumi's Secret: The Life of the Sufi Poet of Love. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-0619-9914-7.

- Lewis, Franklin D. (2014). Rumi - Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi. New York: OneWorld Publications. ISBN 978-1-7807-4737-8.

- Foruzanfar, Badi-uz-zaman (1957). Kulliyat-e Shams. Tehran: Amir Kabir Press.

Critical edition of the collected odes, quatrains and other poems of Rumi with glossary and notes.

- Merwin, W.S. (2002). "Echoes of Rumi". The New York Review of Books.

- Rumi, Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad (1973). Divani Shamsi Tabriz. Translated by Nicholson, Reynold A. San Fransisco: The Rainbow Bridge.

- Foruzanfar, Badi-uz-zaman (2012). "Some Remarks on Rumi's Poetry". Mawlana Rumi Review. 3 (1). Translated by Sorkhabi, Rasoul: 173–186. doi:10.2307/45236338. JSTOR 45236338.

- Vaziri, Mostafa (2015). Rumi and Shams’ Silent Rebellion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-53080-6.