Piva Monastery

| Piva Monastery Pivski Manastir Church of Sveta Bogorodica (the Theotokos) Church of the Assumption of the Holy Mother of God | |

|---|---|

Piva Monastery | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Serbian Orthodox |

| Leadership | Herzeg Metropolitan Savatija |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Piva, Montenegro , Montenegro |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°06′36″N 18°49′07″E / 43.11°N 18.8186°E |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | Original 1573, relocated in 1982 |

| Materials | Stone |

The Piva Monastery (Serbian: Манастир Пивски, romanized: Manastir Pivski), also known as the Church of Sv. Bogorodica or the Church of the Assumption of the Holy Mother of God, is located in Piva, Montenegro near the source of the Piva River in northern Montenegro. Built between 1573 and 1586, it was rebuilt in another location in 1982. It is the largest Serbian Orthodox church constructed during the Ottoman occupation in the 16th and 17th centuries. Noted for its frescoes, the monastery's treasures also include ritual objects, rare liturgical books, art, objects of precious metals and a psalm from the Crnojevići printing press (1493–96), which was the first in the Balkans. These are displayed in the monastery's museum.

History

Founded in 1573,[1] or 1575,[2] and completed in 1586 through the expenditures of the Metropolitan bishop of Zahumlje and Herzegovina Savatije Sokolović,[3] who later became the Serbian Orthodox patriarch,[4] the monastery is dedicated to the Dormition of the Theotokos.[5] The construction workers were brothers named Gavrilo and Vukašin.[6]

Piva Monastery is included within the Eparchy of Budimlja-Nikšić. In 1982, a new reservoir, created by the Piva Hydro Electric Project, required moving the monastery. Stone by stone it was moved to the village of Goransko near Lake Mratinje.[7][8][9]

Geography

Piva Monastery is located in the village of Piva, just south of Goransko in northern Montenegro. It is accessible along the E-762 road, on the way to Foča. It lies approximately 55 kilometres (34 mi) from Nikšić and is 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) south of Plužine.[1]

The monastery was originally located at the source of the Piva River, approximately 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) away from and 100 metres (330 ft) below the junction of the proposed Mratinje Dam, a hydroelectric plant. Begun in 1969 and completed in 1982, the monastery was moved to its current position, which included the removal and replacement of over 1000 fresco fragments, covering 1,260 square metres (13,600 sq ft).[10][4][11]

Architecture and fittings

Piva is a small stone structure.[2][11] Its construction includes three naves with a taller middle nave. There is no cupola. The monastery contains archives, a library, and a treasury with 183 books and nearly 280 other items reported in 1991, including ritual objects, rare liturgical books, art and objects of precious metals.[8][12] Also featured is a psalm from the Crnojevići printing press (1493–1496), which was the first printing press in the Balkans.[8][13] It is dated to 1494 and was discovered by chance among other papers in the library of the monastery.[14]

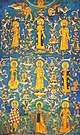

Much of the church was decorated by Greek painters between 1604 and 1606 and contains many frescoes.[15] However, the upper porch area was painted by a local priest Strahinja of Budimlje; this included Akathist to the Mother of God. Other parts of the church, dating from 1626,[16] were painted by Kozma who also painted many of the icons on the iconostasis. The icons of St. George and the Dormition of the Virgin are dated to about 1638–1639.[17] The artist Zograf Longin painted the throne icons of the Mother of God, Christ and Assumption of the Mother of God.[4] Piva, Moraca and Mileseva monasteries have been described as "breathtaking medieval masterpieces that store ancient writings and works of art".[18]

Conservation

The church has been provided with drainage arrangements to prevent seepage of water inside the church so that the frescoes are protected from effects of humidity. In 2008, the U.S. Embassy at Podgorica provided $22,200 for the reconstruction of the drainage system.[10]

See also

- List of Serbian monasteries

- Stanjevići Monastery

- Morača Monastery

- Savina Monastery

- Cetinje Monastery

- Podmaine Monastery

- Reževići Monastery

- Dajbabe Monastery

- Burčele Monastery

- Ostrog Monastery

Gallery

-

Piva Monastery main church from a distance.

-

An aerial view of the Piva Monastery

-

Piva River

References

- ^ a b Abraham, Rudolf (September 2007). The mountains of Montenegro. Cicerone Press Limited. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-85284-506-3. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b Oliver, Ian (2005). War & peace in the Balkans: the diplomacy of conflict in the former Yugoslavia. I.B.Tauris. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-85043-889-2. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ DiLellio, Anna (June 2006). The case for Kosova: passage to independence. Anthem Press. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-1-84331-229-1. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ a b c "Piva Monastery". Museums Macedonia. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Rellie, Annalisa (22 May 2008). Montenegro, 3rd. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 199–. ISBN 978-1-84162-225-5. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Младен Лесковац; Александар Форишковић; Чедомир Попов (2004). Српски биографски речник. Vol. 2. Будућност. p. 570.

- ^ Yugoslav review. Jugoslovenska Revija. 1 January 1986. p. 29. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b c "The Piva monastery". montenegro.org. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Turnock, David (1989). The human geography of Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-415-00469-5. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b Ambassador's Fund Helps Preserve Frescos of Piva Monastery U.S. Embassy in Podgorica and Montenegro (2008)

- ^ a b "The Piva Monastery". discover-montenegro.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Historical abstracts: Modern history abstracts, 1775–1914. American Bibliographical Center, CLIO. 1991. p. 942. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Frederick Bernard Singleton (1985). A short history of the Yugoslav peoples. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Review: Yugoslav magazine. 1979. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Janićijević, Jovan (1998). The cultural treasury of Serbia. IDEA. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Bryer, Anthony; Ursinus, Michael (1991). Manzikert to Lepanto: the Byzantine world and the Turks 1071–1571 : papers given at the Nineteenth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Birmingham, March 1985. A. M. Hakkert. p. 407. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Georgevich, Dragoslav; Maric, Nikola; Moravcevich, Nicholas (1977). Serbian Americans and their communities in Cleveland. Cleveland State University. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Clements, John (1 January 1998). Clements' encyclopedia of world governments. Political Research, inc. Retrieved 19 July 2011.