Malaysia Agreement: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Reverted nowiki added Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Disambiguation links added |

MusikBot II (talk | contribs) m Removing protection templates from unprotected page (more info) Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

In Singapore, the [[People's Action Party]] (PAP) sought an merger with Malaysia based on the powers gained in the 1959 general elections, which won 43 of the 51 seats. It is suspicious when conflicts within the party lead to divisions. In July 1961, after discussions about a vote of no confidence in the government, 13 PAP council members were expelled from the PAP for abstaining. They formed a new political party [[Barisan Sosialis]], which was PAP's majority in the legislature. As they currently hold only 30 of the 51 seats, the defection has soared that the PAP has won a single majority in parliament. Considering this situation It would be impossible to rely on the mandate granted in 1959 to merge. New authority is necessary. Especially when [[Barisan Sosialis|Barisan]] argues that the proposed merger conditions are harmful to Singaporeans (e.g., a reduction in parliamentary seats compared to the population). There is only the ability to vote. in Singapore elections<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tan |first=Kevin Y.L. |title=The Singapore Legal System |publisher=[[NUS Press|Singapore University Press]] |year=1999 |isbn=9789971692124 |volume=2 |page=46}}</ ref> and the commitment that Singapore provides 40% of its revenues to the central government). To alleviate these concerns, a number of [[Singapore in Malaysia#Malaysia Agreement|Singapore-specific provisions]] were included in the agreement<nowiki><ref>. name="HsgSMA"></nowiki>{{cite web |last1=HistorySG |title=Signing of the Malaysia Agreement - Singapore History |url=http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/7fdd00ed-603e-47e0-8e08-f6499d385404 |website=eresources.nlb.gov.sg |publisher=National library committee |Date of access=9 March 2020}}</ref> Although [[Brunei]] had sent a delegation to Malaysia to sign the agreement. But they didn't sign because [[Sultanate of Brunei]] wishes to be recognized as senior ruler in the Federation<ref name="Mathews20142">{{cite book |last=Mathews |first=Philip |url=https://books.google.com/books?id =md9UAgAAQBAJ |title=Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963–2013 |date=February 2014 |publisher=Editions Didier Millet |isbn=978-967-10617-4-9 |pages=29}}</ref> |

In Singapore, the [[People's Action Party]] (PAP) sought an merger with Malaysia based on the powers gained in the 1959 general elections, which won 43 of the 51 seats. It is suspicious when conflicts within the party lead to divisions. In July 1961, after discussions about a vote of no confidence in the government, 13 PAP council members were expelled from the PAP for abstaining. They formed a new political party [[Barisan Sosialis]], which was PAP's majority in the legislature. As they currently hold only 30 of the 51 seats, the defection has soared that the PAP has won a single majority in parliament. Considering this situation It would be impossible to rely on the mandate granted in 1959 to merge. New authority is necessary. Especially when [[Barisan Sosialis|Barisan]] argues that the proposed merger conditions are harmful to Singaporeans (e.g., a reduction in parliamentary seats compared to the population). There is only the ability to vote. in Singapore elections<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tan |first=Kevin Y.L. |title=The Singapore Legal System |publisher=[[NUS Press|Singapore University Press]] |year=1999 |isbn=9789971692124 |volume=2 |page=46}}</ ref> and the commitment that Singapore provides 40% of its revenues to the central government). To alleviate these concerns, a number of [[Singapore in Malaysia#Malaysia Agreement|Singapore-specific provisions]] were included in the agreement<nowiki><ref>. name="HsgSMA"></nowiki>{{cite web |last1=HistorySG |title=Signing of the Malaysia Agreement - Singapore History |url=http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/7fdd00ed-603e-47e0-8e08-f6499d385404 |website=eresources.nlb.gov.sg |publisher=National library committee |Date of access=9 March 2020}}</ref> Although [[Brunei]] had sent a delegation to Malaysia to sign the agreement. But they didn't sign because [[Sultanate of Brunei]] wishes to be recognized as senior ruler in the Federation<ref name="Mathews20142">{{cite book |last=Mathews |first=Philip |url=https://books.google.com/books?id =md9UAgAAQBAJ |title=Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963–2013 |date=February 2014 |publisher=Editions Didier Millet |isbn=978-967-10617-4-9 |pages=29}}</ref> |

||

On September 11, 1963, just four days before the formation of the new Federation of Malaysia. The Government of the State [[Kelantan]] hereby declares that the Malaysian Agreement and the Malaysian Act are invalid. or another way is Even if correct, it does not bind the state of Kelantan. The Kelantan Government argues that neither the Malaysian Agreement nor the Malaysian Act is binding on the Kelantan State. It is for the following reasons that the Malaysian Act has repealed the Federation of Malaya. And this is in contrast to the 1957 Federal Malayan Agreement in which the proposed changes require that Consent of each constituent state of the Federation of Malaya. including Kelantan and this was not consented. The case was dismissed by James Thomson, then Chief Justice. which ruled that the constitution was not violated during discussions and drafting of Malaysian law<ref>Re-admission: the Kelantan Government and the Government of the Federation of Malaya and Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj [https://www.jstor.org/stable/24861976?seq=1] {{PD-notice}}</ref><ref>{{Web reference |last=Kathirasen |first=A |date=2020-09-09 |title=When Kelantan (and PMIP) sued to stop the establishment of Malaysia |url=https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/opinion/2020/09/09/when-kelantan- and-pmip-sued-to-stop-formation-of-malaysia/ |website=FMT |Access Date=2021- 03-31}}</ref> |

On September 11, 1963, just four days before the formation of the new Federation of Malaysia. The Government of the State [[Kelantan]] hereby declares that the Malaysian Agreement and the Malaysian Act are invalid. or another way is Even if correct, it does not bind the state of Kelantan. The Kelantan Government argues that neither the Malaysian Agreement nor the Malaysian Act is binding on the Kelantan State. It is for the following reasons that the Malaysian Act has repealed the Federation of Malaya. And this is in contrast to the 1957 Federal Malayan Agreement in which the proposed changes require that Consent of each constituent state of the Federation of Malaya. including Kelantan and this was not consented. The case was dismissed by James Thomson, then Chief Justice. which ruled that the constitution was not violated during discussions and drafting of Malaysian law<ref>Re-admission: the Kelantan Government and the Government of the Federation of Malaya and Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj [https://www.jstor.org/stable/24861976?seq=1] {{PD-notice}}</ref><ref>{{Web reference |last=Kathirasen |first=A |date=2020-09-09 |title=When Kelantan (and PMIP) sued to stop the establishment of Malaysia |url=https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/opinion/2020/09/09/when-kelantan- and-pmip-sued-to-stop-formation-of-malaysia/ |website=FMT |Access Date=2021- 03-31}}</ref> |

||

{{LOCKED}} |

|||

=== Perjanian Documen: === |

=== Perjanian Documen: === |

||

Revision as of 13:50, 11 April 2023

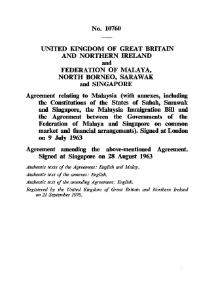

| Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore | |

|---|---|

Agreement relating to Malaysia | |

| Drafted | 15 November 1961 |

| Signed | 9 July 1963 |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Sealed | 31 July 1963 |

| Effective | 16 September 1963 |

| Signatories | |

| Parties |

|

| Depositary |

|

| Languages | English, Malay |

| Full text | |

The Malaysia Agreement or the Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore (MA63) was the agreement which combined North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore with the existing states of the Federation of Malaya,[3] the resulting union being named Malaysia.[4][5] Singapore was later expelled from Malaysia, becoming an independent state on 9 August 1965.[6]

Background

The Malayan Union was established by the British Malaya and comprised the Federated Malay States of Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang; the Unfederated Malay States of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, Terengganu, Johor; and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca. It came into being in 1946, through a series of agreements between the United Kingdom and the Malayan Union.[7] The Malayan Union was superseded by the Federation of Malaya on 1 February 1948, and achieved independence within the Commonwealth of Nations on 31 August 1957.[5]

After the end of the Second World War, decolonisation became the societal goal of the peoples under colonial regimes aspiring to achieve self-determination. The Special Committee on Decolonisation (also known as the U.N. Special Committee of the 24 on Decolonisation, reflected in the United Nations General Assembly's proclamation on 14 December 1960 of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples hereinafter, the Committee of 24, or simply, the Decolonisation Committee) was established in 1961 by the General Assembly of the United Nations with the purpose of monitoring implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples and to make recommendations on its application.[8] The committee is also a successor to the former Committee on Information from Non-Self-Governing Territories. Hoping to speed the progress of decolonisation, the General Assembly had adopted in 1960 the Resolution 1514, also known as the "Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples" or simply "Declaration on Decolonisation". It stated that all people have a right to self-determination and proclaimed that colonialism should be brought to a speedy and unconditional end.[9]

Under the Malaysia Agreement signed between Great Britain and the Federation of Malaya, Britain would enact an act to relinquish sovereign control over Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo (now Sabah). This was accomplished through the enactment of the Malaysia Act 1963, clause 1(1) of which states that on Malaysia Day, "Her Majesty’s sovereignty and jurisdiction in respect of the new states shall be relinquished so as to vest in the manner agreed".[10]

Decolonisation, self-determination and referendum

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

https://ms.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmad_Mulkliff_Bin_Mohd_Nor}®{https://m.wikidata.org/ https://ms.wiki/Q5244614.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmad_Mulkliff_Bin_Mohd_Nor

Template:Use date dmy Template:Perjanjian Kotak InfoTemplate:Brief Description Template:Malaysia formation Malaysia Agreement' or Agreement relating to Malaysia between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland federation of malaya North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore (MA63) is an agreement combining North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore with the existing state of Federation of Malaya ,[11] As a result, a union named Malaysia.[12][13] Singapore was later expelled from Malaysia. and became an independent state on 9 August 1965[14]

Background

Malay Union established by British Malaya and consisting of Federated Malay States of Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang ; Unfederated Malay States of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, Terengganu, Johor; and the Straits Settlement of Penang and Melaka. It arose in 1946 through a series of agreements between the United Kingdom and the Malaya Union[15] The Malay Union was replaced by Federation of Malaya on February 1, 1948 and gained independence within Commonwealth of Nations on August 31, 1957[13]

After the end of World War II, colonial liberation became a social goal of the people under the colonial regime who wished to achieve self-determination. The Special Committee on Colonialism (also known as The 24th United Nations Special Committee on Colonialism is reflected in the United Nations General Assembly's Declaration of 14 December 1960 on the Declaration on the Granting of Colonial Independence. and the people, hereinafter referred to as Committee 24 or simply Colonial Eradication Committee) was established in 1961 by General Assembly of [[UN] ]. with the purpose of tracking compliance Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples and to provide guidance on its implementation[16] The Committee is also the successor to the former Commission on Information from Non-Autonomous Territories. with the hope of speeding up the progress of colonial liberation The Assembly adopted Resolution 1514 in 1960, known as the "Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples" or simply the "Declaration on Hunting. Colony" states that every citizen has the right to self-determination. and declares that colonialism should be ended swiftly and unconditionally[17] Under the Malaysia Agreement signed between Great Britain and the Federation of Malaya Britain will pass legislation to renounce its sovereignty over Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo. (now Sabah). This was accomplished by the enactment of the Law Malaysia Act 1963, Article 1(1), which states that on Malaysia Day, "Her Majesty's sovereignty and jurisdiction in respect of the new State shall be rescinded to vest in Agreed nature".[18]

=== Liberation, self determination and referendum ===

Template:See more The issue of self-determination with respect to the people of North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore was the foundation of another challenge to the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. Under a joint statement issued by the British and Central Malayan governments on 23 November 1961, Article 4 states that "before a final decision is made, It is necessary to verify public opinion to be sure. So it was decided to establish a committee to carry out this task and give advice........

With the spirit of ensuring that the decolonization action meets the wishes of the people of North Borneo,

The British government, working with the Federation of Malaya, set up a Commission of Inquiry for North Borneo and Sarawak in January 1962 to determine whether the people supported a proposal to create a Federation of Malaysia. 2 and 3 English representatives led by Lord Cobbold[19]

In Singapore, the People's Action Party (PAP) sought an merger with Malaysia based on the powers gained in the 1959 general elections, which won 43 of the 51 seats. It is suspicious when conflicts within the party lead to divisions. In July 1961, after discussions about a vote of no confidence in the government, 13 PAP council members were expelled from the PAP for abstaining. They formed a new political party Barisan Sosialis, which was PAP's majority in the legislature. As they currently hold only 30 of the 51 seats, the defection has soared that the PAP has won a single majority in parliament. Considering this situation It would be impossible to rely on the mandate granted in 1959 to merge. New authority is necessary. Especially when Barisan argues that the proposed merger conditions are harmful to Singaporeans (e.g., a reduction in parliamentary seats compared to the population). There is only the ability to vote. in Singapore elections[20] Although Brunei had sent a delegation to Malaysia to sign the agreement. But they didn't sign because Sultanate of Brunei wishes to be recognized as senior ruler in the Federation[21]

On September 11, 1963, just four days before the formation of the new Federation of Malaysia. The Government of the State Kelantan hereby declares that the Malaysian Agreement and the Malaysian Act are invalid. or another way is Even if correct, it does not bind the state of Kelantan. The Kelantan Government argues that neither the Malaysian Agreement nor the Malaysian Act is binding on the Kelantan State. It is for the following reasons that the Malaysian Act has repealed the Federation of Malaya. And this is in contrast to the 1957 Federal Malayan Agreement in which the proposed changes require that Consent of each constituent state of the Federation of Malaya. including Kelantan and this was not consented. The case was dismissed by James Thomson, then Chief Justice. which ruled that the constitution was not violated during discussions and drafting of Malaysian law[22][23] Template:LOCKED

Perjanian Documen:

{LOCKED} Appearance Campylobacter

Annex A: Timeline for Adoption of Malaysian Laws - New Constitutional Amendment Annex Aidarg II - Idftan's Constitutional Affirmation Analysis Table - Citizenship (Choice of parents) in the near future. Law B: Term of the Constitution of the Three Provinces - Permanent Written Speech and Crown c. Appendix F: Service Agreement and Appendix. In addition, the first component: Shamlot - the Hadith of Eid Al-Fajr from the Gulf Agreement, and the Addendum - the stomping rhythm.

The Agreement states: Another obstacle to the formation of the Malaysian Federation is the self-determination problem in North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore, and public consultation is required. Therefore, a committee was established to work and give advice on this matter. To make the colony self-governing to meet the needs of the people of North Borneo. The British and Central Malaya governments established the North Borneo and Sarawak Survey Committee in January 1962 in Singapore. The People's Party (Sai Si) decided to withdraw to Malaysia in 1959, winning 43 seats. Of the party's 51 seats. The lack of a vote in government reduced the PAP's majority in parliament and led to the formation of a new socialist political party, which has only 30 seats. It currently has 51 seats in the National Assembly. This situation required a new mandate when we considered that the 1959 mandate could not be based on consolidation. Vote exclusively in Singapore elections[12] (and Singapore has pledged to allocate 40 per cent of its revenues to the central government). Several Singapore provisions are included in the agreement to alleviate these concerns. It is the new federation of Malaysia.

And the Kelantan Government has declared the Malaysian Convention and Malaysian law invalid. A cheaper option is gluten-free. The Kelantan Government argues that neither the Malaysian Convention nor the Malaysian law binds the Kelantan State. As a result, Malaysian law replaces the Federation of Malaya for the following reasons: Unlike the 1957 proposal to replace the Federation of Malaya

Malaya's central government institutions - including Kelantan - don't understand this. deny the allegations This means that this does not violate the Malaysian Constitution and applicable law.[15][16] |- | Appendix B: The Sabah State Constitution |- | Schedule—Oath and Confirmation Forms |- | Annex C: The Sarawak Constitution |- | Schedule—Oath and Confirmation Forms |- | Annex D: The State Constitution of Singapore |- | First Schedule—Oath and Confirmation Forms |- | Table Two—The Oath of Allegiance and Loyalty |- | Third Schedule—The Oath of Legislature |- | Annex F: Agreement on External Defense and Mutual Assistance |- | Annex G: North Borneo's (Compensation and Retirement Benefits) Directive 1963 |- Appendix H: Government Official Agreement Form with respect to Sabah and Sarawak |- | Annex I: Singapore Government Official Agreement Form |- | Annex J: Agreement between the Government of the Federal Government of Malaya and Singapore on Mutual and Financial Agreements |- |   ; |-

| Annex K: Broadcasting and Television Agreement in Singapore

|}

== 2019 Agreement Review == After Malaysian constitutional amendment proposed 2019 regarding equal status of Sabah and Sarawak failed. The Malaysian central government agreed to review the agreement to address treaty violations with "A special cabinet committee to review Malaysia Agreement"[24][25] The seven agreed upon issues are:

* Export duty claims in Recording Exports and Forest Products * Gas Distribution and Regulatory Authority on Electricity and Gas * Operations of Federal and State Public Works. * Manpower. * State power on issueshealth * Island administration Sipadan and Lijitan for the state of Sabah. * Agriculture and Forestry Problems

The first meeting on these issues was held on 17 December 2018[26]. But talks between Sabah and the central government reportedly have not gone smoothly. with the latter stipulating some matters of inspection It creates the perception that the review is on the side of the government. appears reluctant to relinquish control of the entity[27]

View more

* 18-point agreement * 20 point deal * Amendment to the 2021 Constitution * Cobb Commission * Singapore Independence Agreement 1965 * Confrontation between Indonesia - Malaysia * Malaysia Act B.E. 2506 * Manila Agreement * Separation Movement in Malaysia * Malaysian history timeline * Singapore notice * Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties == Reference ==

== External Links == * Hansard Parliament of the United Kingdom Malaysia Bill * Malaysia Act 1963 * applies to Malaysia Act 1963 * symbol=A/RES/60/119 Solidarity with the Peoples of Non-Self-Governing Territories by Resolution of the General Assembly No. 60/119 dated 18 January 2006 * Trust and Non-Governing Territories listed by United Nations General Assembly . * 18th Session of the United Nations General Assembly - The Malaysian Question (Pages:41-44) * Malaysia Timeline by BBC News Channel.

== Read more == * J. de V. Allen; Anthony J. Stockwell. Compilation of treaties and other documents Affecting the Malaysian State: 1761-1963. ISBN 978-0379007817.{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) * "Federal-East Malaysia Relations: Primus-Inter-Pares?, in Andrew Harding and James Chin (eds) 50 Years of Malaysia: Federalism. Another Visit (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish)". The Straits Times: 152–185. 2014 – via Academia.edu.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) * James Chin (31 May 2018). "Why Malaysia's new government must listen to MA63 calling for demonstrations". The Straits Times – via Academia.edu. *James Chin (2019) The 1963 Malaysia Agreement (MA63): Sabah And Sarawak and the Politics of Historical Grievances - via ResearchGate.

Section: Legal Documents Section:Malaysia Treaties Section:Malaya Federation Treaty Section: Sarawak Treaty Section: Singapore Treaty

The issue of self-determination with respect to the peoples of North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore formed the bedrock of yet another challenge to the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. Under the Joint Statement issued by the British and Malayan Federal Governments on 23 November 1961, clause 4 provided: Before coming to any final decision it is necessary to ascertain the views of the peoples. It has accordingly been decided to set up a Commission to carry out this task and to make recommendations ........

In the spirit of ensuring that decolonisation was carried in accordance with the wishes of the peoples of North Borneo, the British Government, working with the Federation of Malaya Government, appointed a Commission of Enquiry for North Borneo and Sarawak in January 1962 to determine if the people supported the proposal to create a Federation of Malaysia. The five-man team, which comprised two Malayans and three British representatives, was headed by Lord Cobbold.[28]

In Singapore, the People's Action Party (PAP) sought merger with Malaysia on the basis of the strong mandate it obtained during the general elections of 1959 when it won 43 of the 51 seats. However, this mandate became questionable when dissension within the Party led to a split. In July 1961, following a debate on a vote of confidence in the government, 13 PAP Assemblymen were expelled from the PAP for abstaining. They went on to form a new political party, the Barisan Sosialis, the PAP’s majority in the Legislative Assembly was whittled down as they now only commanded 30 of the 51 seats. More defections occurred until the PAP had a majority of just one seat in the Assembly. Given this situation, it would have been impossible to rely on the mandate achieved in 1959 to move forth with merger. A new mandate was necessary, especially since the Barisan argued that the terms of merger offered were detrimental to the Singapore people (such as having reduced seats in the federal parliament compared to its population, only being able to vote in Singapore elections,[29] and the obligation that Singapore contribute 40% of its revenue to the federal government). In order to allay these concerns, a number of Singapore-specific provisions were included in the Agreement.[30]

While Brunei sent a delegation to the signing of the Malaysia Agreement, they did not sign as the Sultan of Brunei wished to be recognised as the senior ruler in the federation.[31]

On 11 September 1963, just four days before the new Federation of Malaysia was to come into being, the Government of the State of Kelantan sought a declaration that the Malaysia Agreement and Malaysia Act were null and void, or alternatively, that even if they were valid, they did not bind the State of Kelantan. The Kelantan Government argued that both the Malaysia Agreement and the Malaysia Act were not binding on Kelantan on the following grounds that the Malaysia Act in effect abolished the Federation of Malaya and this was contrary to the 1957 Federation of Malaya Agreement that the proposed changes required the consent of each of the constituent states of the Federation of Malaya – including Kelantan – and this had not been obtained. This suit was dismissed by James Thomson, then Chief Justice, who ruled that the constitution had not been violated during the discussion and creation of the Malaysia Act.[32][33]

Documents

The Malaysia Agreement lists annexes of

| Annex A: Malaysia Bill |

| First Schedule—Insertion of new Articles in Constitution |

| Second Schedule—Section added to Eighth Schedule to Constitution |

| Third Schedule—Citizenship (amendment of Second Schedule to Constitution) |

| Fourth Schedule—Special Legislative Lists for Borneo States and Singapore |

| Fifth Schedule—Additions for Borneo States to Tenth Schedule (Grants and assigned revenues) to Constitution |

| Sixth Schedule—Minor and consequential amendments of Constitutions |

| Annex B: The Constitution of the State of Sabah |

| The Schedule—Forms of Oaths and Affirmations |

| Annex C: The Constitution of the State of Sarawak |

| The Schedule—Forms of Oaths and Affirmations |

| Annex D: The Constitution of the State of Singapore |

| First Schedule—Forms of Oaths and Affirmations |

| Second Schedule—Oath of Allegiance and Loyalty |

| Third Schedule—Oath as Member of the Legislative Assembly |

| Annex F: Agreement of External Defence and Mutual Assistance |

| Annex G: North Borneo (Compensation and Retiring benefits) Order in Council, 1963 |

| Annex H: Form of public officers agreements in respect of Sabah and Sarawak |

| Annex I: Form of public officers agreements in respect of Singapore |

| Annex J: Agreement between the Governments of the Federation of Malaya and Singapore on common and financial arrangements |

| Annex to Annex J—Singapore customs ordinance |

| Annex K: Arrangements with respect to broadcasting and television in Singapore |

2019 review of the agreement

After the proposed 2019 amendment to the Constitution of Malaysia on the equal status of Sabah and Sarawak failed to pass, the Malaysian federal government agreed to review the agreement to remedy breaches of the treaty with a "Special Cabinet Committee To Review the Malaysia Agreement".[34][35] The seven agreed issues were:

- Export duty claims on logging exports and forest products.

- Gas distribution and regulatory powers on electricity and gas.

- Implementation of Federal and State Public Works.

- Manpower.

- The power of the state on health issues.

- Administration of Sipadan and Ligitan islands for Sabah.

- Agricultural and forestry issues.

The first meeting about these issues was held on 17 December 2018.[35] Despite the willingness of the federal government to review the agreement, reports surfaced that negotiations between Sabah and the federal government had not been smooth, with the latter dictating some matters of the review, causing the perception that the review was a one-sided affair with the government appearing reluctant to relinquish control of affairs.[36]

See also

- 18-point agreement

- 20-point agreement

- 2021 amendment to the Constitution of Malaysia

- Cobbold Commission

- Independence of Singapore Agreement 1965

- Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation

- Malaysia Act 1963

- Manila Accord

- Separatist movements in Malaysia

- Timeline of Malaysian history

- Proclamation of Singapore

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties

References

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Resolution 97 (1).

- ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). web.archive.org. 14 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Malaysia Act 1963".

- ^ See: The UK Statute Law Database: the Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom Malaysia Act 1963

- ^ a b See: The UK Statute Law Database: the Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom Federation of Malaya Independence Act 1957 (c. 60)

- ^ See: the Independence of Singapore Agreement 1965 and the Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom Singapore Act 1966.

- ^ See: Cabinet Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Colonies. 21 February 1956 Federation of Malaya Agreement

- ^ See: the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonisation - Official Website

- ^ See: History of U.N. Decolonisation Committee - Official U.N. Website

- ^ See: Section 1(1), Malaysia Act 1963, Chapter 35 (UK).

- ^ 1 "Malaysia Act 1963".

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ See: The UK Statute Law Database: the Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom /ukpga/1963/35/contents Malaysia Act 1963

- ^ a b See: The UK Statute Law Database: the Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom gov.uk/ukpga/Eliz2/5-6/60/contents Independent Malaya Federation Act 1957 (c. 60)

- ^ See: the Volume%20563/volume-563- I-8206-English.pdf The Independence of Singapore Agreement 1965 and the United Kingdom Parliament Act. Content Singapore Act 1966.

- ^ See: Cabinet Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Colony, 21 February 1956 -79.pdf Malaya Federal Agreement

- ^ See: org/Depts/dpi/decolonization/extra_board_main.htm UN Special Committee on Colonial Liberation - Official Website

- ^ See: decolonization/history.htm History of the UN Colonial Decommissioning Committee - UN Official Website

- ^ See: Section 1(1), Malaysia Act 1963, Chapter 35 (United Kingdom).

- ^ Cobbold Was governor of the Bank of England from 1949 to 1961. Another member is Wong Pow Nee, Penang Chief Minister, Mohammed Ghazali Shafie, Undersecretary of State, [[Anthony Abell]. ], Former Governor of Sarawak and David Watherston, Former Chief Secretary of Malaya Federation

- ^ Tan, Kevin Y.L. (1999). The Singapore Legal System. Vol. 2. Singapore University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9789971692124.</ ref> and the commitment that Singapore provides 40% of its revenues to the central government). To alleviate these concerns, a number of Singapore-specific provisions were included in the agreement<ref>. name="HsgSMA">HistorySG. "Signing of the Malaysia Agreement - Singapore History". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. National library committee.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Date of access=ignored (help) - ^ Mathews, Philip (February 2014). =md9UAgAAQBAJ Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963–2013. Editions Didier Millet. p. 29. ISBN 978-967-10617-4-9.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Re-admission: the Kelantan Government and the Government of the Federation of Malaya and Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj [1]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Kathirasen, A (9 September 2020). and-pmip-sued-to-stop-formation-of-malaysia/ "When Kelantan (and PMIP) sued to stop the establishment of Malaysia". FMT.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|Access Date=ignored (help) - ^ says-pms-office/1782156 "MA63: Seven Issues Resolved, 14 Require Further Discussion The prime minister's office says". Bernama. The Malay Mail. 19 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Seven MA63 problem solved". 20 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

seven MA63 Issueswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/09/02/in-sabah-doubts-linger-as-putrajayas-ma63-review-accused-of- being-one-sided/ 1786329 "In Sabah Suspicion Remains as Putrajaya's MA63 Review is Accused of being One-sided".

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Date=ignored (|date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Cobbold was Governor of the Bank of England from 1949 to 1961. The other members were Wong Pow Nee, Chief Minister of Penang, Mohammed Ghazali Shafie, Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Anthony Abell, former Governor or Sarawak, and David Watherston, former Chief Secretary of the Federation of Malaya.

- ^ Tan, Kevin Y.L. (1999). The Singapore Legal System. Vol. 2. Singapore University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9789971692124.

- ^ HistorySG. "Signing of the Malaysia Agreement - Singapore History". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. National Library Board. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Mathews, Philip (February 2014). Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963–2013. Editions Didier Millet. p. 29. ISBN 978-967-10617-4-9.

- ^ Admission of New States: The Government of the State of Kelantan v. The Government of the Federation of Malaya and Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj

[2]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Kathirasen, A. (9 September 2020). "When Kelantan (and PMIP) sued to stop formation of Malaysia". FMT. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "MA63: Seven issues resolved, 14 need further discussion, says PM's Office". Bernama. The Malay Mail. 19 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Seven MA63 issues resolved". Bernama. Daily Express. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Julia Chan (2 September 2019). "In Sabah, doubts linger as Putrajaya's MA63 review accused of being one-sided affair". The Malay Mail. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

External links

- Hansard of Parliament of the United Kingdom Malaysia Bill

- Malaysia Act 1963

- Affecting the Malaysia Act 1963

- Solidarity with the Peoples of Non-Self-Governing Territories by Resolution of General Assembly 60/119 of 18 January 2006

- Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories listed by the United Nations General Assembly.

- United Nations General Assembly 18th Session - the Question of Malaysia (pages:41-44)

- Malaysia Timeline by the BBC News Channel.

Further reading

- J. de V. Allen; Anthony J. Stockwell (1981). A Collection of Treaties and Other Documents Affecting the States of Malaysia: 1761-1963. Oceana Publ. ISBN 978-0379007817.

- James Chin (2014). "Federal-East Malaysia Relations: Primus-Inter-Pares?, in Andrew Harding and James Chin (eds) 50 Years of Malaysia: Federalism Revisited (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish)". The Straits Times: 152–185 – via Academia.edu.

- James Chin (31 May 2018). "Why new Malaysian govt must heed MA63 rallying cry". The Straits Times – via Academia.edu.

- James Chin (2019) The 1963 Malaysia Agreement (MA63): Sabah And Sarawak and the Politics of Historical Grievances - Via ResearchGate