Palestinians: Difference between revisions

→DNA clues: started to provide some sense of the argument, but I don't see or understand which evidence supports the prehistoric claim, sorry, not my field |

clean up again, remove various editorial comments or unrelated claims |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Following the 1948 [[Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel|establishment]] of the [[State of Israel]] as the national homeland of the [[Jewish people]], the use and application of the terms "Palestine" and "Palestinian" by and to [[Palestinian Jews]] largely dropped from use. The English-language newspaper ''[[The Palestine Post]]'' for example — which, since 1932, primarily served the [[Yishuv|Jewish community]] in the [[British Mandate of Palestine]] — changed its name in 1950 to ''[[The Jerusalem Post]]''. Today, Jews in [[Israel]] and the [[West Bank]] generally identify as [[Israelis]]. It is common for [[Arab citizens of Israel]] to identify themselves as both Israeli and Palestinian and/or Palestinian Arab or Israeli Arab.<ref>Kershner, Isabel. [http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/02/08/africa/web.0208israel.php "Noted Arab citizens call on Israel to shed Jewish identity"] ''International Herald Tribune''. 8 February 2007. 1 August 2007.</ref> |

Following the 1948 [[Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel|establishment]] of the [[State of Israel]] as the national homeland of the [[Jewish people]], the use and application of the terms "Palestine" and "Palestinian" by and to [[Palestinian Jews]] largely dropped from use. The English-language newspaper ''[[The Palestine Post]]'' for example — which, since 1932, primarily served the [[Yishuv|Jewish community]] in the [[British Mandate of Palestine]] — changed its name in 1950 to ''[[The Jerusalem Post]]''. Today, Jews in [[Israel]] and the [[West Bank]] generally identify as [[Israelis]]. It is common for [[Arab citizens of Israel]] to identify themselves as both Israeli and Palestinian and/or Palestinian Arab or Israeli Arab.<ref>Kershner, Isabel. [http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/02/08/africa/web.0208israel.php "Noted Arab citizens call on Israel to shed Jewish identity"] ''International Herald Tribune''. 8 February 2007. 1 August 2007.</ref> |

||

=== The |

=== The Origins of the Palestinian identity === |

||

In his 1997 book, ''Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness,'' historian [[Rashid Khalidi]] argues that the identity of Palestinians has its roots in [[nationalism|nationalist]] discourses that emerged among the peoples of the [[Ottoman empire]] in the late 19th century. Such discourses sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state boundaries in the [[Middle East]] after [[World War I]].<ref name=Khalidip18>{{cite book|title=Palestinian Identity:The Construction of Modern National Consciousness|publisher=[[Columbia University Press]]|year=1997|page=18|isbn=0231105142}}</ref> Khalidi states that the archaeological strata that denote the history of [[Palestine]] - encompassing the [[biblical]], [[Roman]], [[Byzantine]], [[Umayyad]], [[Fatimid]], [[Crusade]]r, [[Ayyubid]], [[Mamluk]] and [[Ottoman empire|Ottoman]] periods - form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people, as they have come to understand it over the last century.<ref name=Khalidip18>{{cite book|title=Palestinian Identity:The Construction of Modern National Consciousness|publisher=[[Columbia University Press]]|year=1997|page=18|isbn=0231105142}}</ref><ref name=WKhalidi>{{cite book|title=Before Their Diaspora|author=Walid Khalidi|publisher=Institute for Palestine Studies, Washington D.C.|year=1984|page=32}}[[Walid Khalidi]] echoes this view stating that Palestinians in [[Ottoman empire|Ottoman]] times were "[a]cutely aware of the distinctiveness of Palestinian history..." and that "[a]lthough proud of their Arab heritage and ancestry, the Palestinians considered themselves to be descended not only from Arab conquerors of the seventh century but also from [[indigenous peoples]] who had lived in the country since time immemorial, including the ancient [[Hebrews]] and the [[Canaanites]] before them.</ref> He stresses that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive one, with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" continuing to play an important role.<ref name=Khalidip19>Khalidi 1997:19–21</ref> Khalidi also states that although the challenge posed by [[Zionism]] played a role in shaping this identity, that "it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism."<ref name=Khalidip19/> |

|||

In contrast, historian [[James L. Gelvin]] argues that [[Palestinian nationalism]] was a direct reaction to Zionism. In his book ''The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War'' he states that “Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement.”<ref name = "Gelvin 92">{{cite book |

In contrast, historian [[James L. Gelvin]] argues that [[Palestinian nationalism]] was a direct reaction to Zionism. In his book ''The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War'' he states that “Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement.”<ref name = "Gelvin 92">{{cite book |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

</blockquote> |

</blockquote> |

||

Whatever the causal mechanism, by the early 20th century |

Whatever the causal mechanism, by the early 20th century trong opposition to Zionism and evidence of a burgeoning nationalistic Palestinian identity is found in the content of Arabic-language newspapers in Palestine, such as ''Al-Karmil'' (est. 1908) and ''Filasteen'' (est. 1911).<ref name=Khalidip124>Khalidi 1997:124 - 127</ref> ''Filasteen'', published in [[Jaffa]] by Issa and Yusef al-Issa, addressed its readers as "Palestinians".<ref>{{cite web|title=Palestine Facts|publisher=PASSIA: Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs|url=http://www.passia.org/palestine_facts/chronology/14001962.htm}}</ref> The newspaper initially focused its critique of Zionism around the failure of the Ottoman administration to control Jewish immigration and the large influx of foreigners, and later on the impact of Zionist land-purchases on Palestinian peasants ([[fellaheen]]), expressing growing concern over land dispossession and its implications for the society at large.<ref name=Khalidip124/> |

||

The historical record also gives mixed signals about the interplay between "Arab" and "Palestinian" identities and nationalisms. The idea of a unique Palestinian state separated out from its Arab neighbors was at first rejected by some Palestinian representatives. The First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (in [[Jerusalem]], February 1919), which met for the purpose of selecting a Palestinian Arab representative for the [[Paris Peace Conference, 1919|Paris Peace Conference]], adopted the following resolution: "We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, [[linguistic]], natural, economic and geographical bonds."<ref>{{cite book|title=Palestinian Arab National Movement: From Riots to Rebellion: 1929-1939, vol. 2|author=[[Yehoshua Porath]]|publisher=Frank Cass and Co., Ltd.|date=1977|page=81-82}}</ref> After the fall of the [[Ottoman Empire]] and the French conquest of [[Syria]], however, the notion took on greater appeal. In 1920, for instance, the formerly pan-Syrianist [[mayor of Jerusalem]], [[Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni]], said "Now, after the recent events in [[Damascus]], we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria no longer exists. We must defend Palestine". |

The historical record also gives mixed signals about the interplay between "Arab" and "Palestinian" identities and nationalisms. The idea of a unique Palestinian state separated out from its Arab neighbors was at first rejected by some Palestinian representatives. The First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (in [[Jerusalem]], February 1919), which met for the purpose of selecting a Palestinian Arab representative for the [[Paris Peace Conference, 1919|Paris Peace Conference]], adopted the following resolution: "We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, [[linguistic]], natural, economic and geographical bonds."<ref>{{cite book|title=Palestinian Arab National Movement: From Riots to Rebellion: 1929-1939, vol. 2|author=[[Yehoshua Porath]]|publisher=Frank Cass and Co., Ltd.|date=1977|page=81-82}}</ref> After the fall of the [[Ottoman Empire]] and the French conquest of [[Syria]], however, the notion took on greater appeal. In 1920, for instance, the formerly pan-Syrianist [[mayor of Jerusalem]], [[Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni]], said "Now, after the recent events in [[Damascus]], we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria no longer exists. We must defend Palestine". |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

Conflict between Palestinian nationalists and various types of [[Pan-Arabism|pan-Arabists]] continued during the British Mandate, but the latter became increasingly marginalised. A prominent leader of the Palestinian nationalists was [[Mohammad Amin al-Husayni]], Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. By 1937, only one of the many Arab political parties in Palestine (the Istiqlal party) promoted political absorption into a greater Arab nation as its main agenda. During World War II, al-Husayni maintained close relations with [[Nazi]] officials seeking German support for an independent Palestine.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} However, the [[1948 Arab-Israeli War]] resulted in those parts of Palestine which were not part of Israel being occupied by Egypt and Jordan. |

Conflict between Palestinian nationalists and various types of [[Pan-Arabism|pan-Arabists]] continued during the British Mandate, but the latter became increasingly marginalised. A prominent leader of the Palestinian nationalists was [[Mohammad Amin al-Husayni]], Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. By 1937, only one of the many Arab political parties in Palestine (the Istiqlal party) promoted political absorption into a greater Arab nation as its main agenda. During World War II, al-Husayni maintained close relations with [[Nazi]] officials seeking German support for an independent Palestine.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} However, the [[1948 Arab-Israeli War]] resulted in those parts of Palestine which were not part of Israel being occupied by Egypt and Jordan. |

||

The Israeli capture of the [[Gaza Strip]] and [[West Bank]] in the 1967 [[Six-Day War]] prompted existing but fractured Palestinian political and militant groups to give up any remaining hope they had placed in [[pan-Arabism]] and to rally around the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), (which was founded in 1964), to organize efforts to establish an independent Palestinian state.<ref name=Hassassian>{{cite web|title=From Armed Struggle to Negotiation|author=Manuel Hassassian|publisher=Palestine-Israel Journal|date=1994|accessdate=07.16.2007|url=http://www.pij.org/details.php?id=767}}</ref> Mainstream [[secular]] Palestinian nationalism was grouped together under the umbrella of the PLO whose constituent organizations include [[Fateh]] and the [[Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine]], among others. <ref name=Khalidi149>Khalidi 1997: 149</ref> These groups have also given voice to a tradition that emerged in 1960s that argues that Palestinian nationalism has deep historical roots, with extreme advocates reading a Palestinian nationalist consciousness and identity back into the history of Palestine over the past few centuries, and even millenia, when such consciousness of their identity as Palestinians is in fact relatively modern.<ref name=Khalidi149/> From the 1960s onward, consequently, the term "Palestine" was regularly used in political contexts. Various declarations, such as the PLO's 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine, serve to reinforce the Palestinian national identity. |

|||

Nevertheless, Palestinian expressions of pan-Arabist sentiment are still be heard from time to time. For example, [[Zuhayr Muhsin]], the leader of the Syrian-funded [[as-Sa'iqa]] Palestinian faction and its representative on the PLO Executive Committee, told a [[Netherlands|Dutch]] newspaper in 1977 that "There is no difference between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese. It is for political reasons only that we carefully emphasize our Palestinian identity."{{Fact|date=July 2007}} However, most Palestinian organizations conceived of their struggle as either Palestinian-nationalist or Islamic in nature, and these themes predominate even more today. Within Israel itself, there are political movements, such as [[Abnaa el-Balad]] that assert their Palestinian identity, to the exclusion of their Israeli one. |

Nevertheless, Palestinian expressions of pan-Arabist sentiment are still be heard from time to time. For example, [[Zuhayr Muhsin]], the leader of the Syrian-funded [[as-Sa'iqa]] Palestinian faction and its representative on the PLO Executive Committee, told a [[Netherlands|Dutch]] newspaper in 1977 that "There is no difference between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese. It is for political reasons only that we carefully emphasize our Palestinian identity."{{Fact|date=July 2007}} However, most Palestinian organizations conceived of their struggle as either Palestinian-nationalist or Islamic in nature, and these themes predominate even more today. Within Israel itself, there are political movements, such as [[Abnaa el-Balad]] that assert their Palestinian identity, to the exclusion of their Israeli one. |

||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

{{main|Palestinian pottery}} |

{{main|Palestinian pottery}} |

||

Modern pots, bowls, jugs and cups produced by Palestinians, particularly those produced prior to the 1940s, are similar in shape, fabric and decoration to their ancient equivalents.<ref name=Needler>{{cite book|title=''Palestine: Ancient and Modern''|author=Winifred Needler|publisher=Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology|year=1949|page=75 - 76}}</ref> Cooking pots, jugs, mugs and plates that are still hand-made and fired in open, charcoal-fuelled kilns as in ancient times in historic villages like [[Jib (village)|al-Jib]] ([[Gibeon]]), Beitin ([[Bethel]]) and Senjel.<ref name=PACE>{{cite web|title=PACE's Exhibit of Traditional Palestinian Handicrafts|publisher=PACE|accessdate=13.07.2007|url=http://www.pace.ps/handi/handi.html}}</ref> |

|||

{{cquote|... the division into periods [of Palestinian pottery] is to some extent a necessary evil, in that it suggests a misleading idea of discontinuity - as though the periods were so many water-tight compartments with fixed partitions between them. In point of fact, each period shades almost imperceptibly into the next.<ref name=Macalister131>{{cite book|title=The Excavation of Gezer: 1902 - 1905 and 1907 - 1909|author=R.A. Stewart Macalister|publisher=John Murray, Albemarle Street West, London|year=1912|url=http://www.case.edu/univlib/preserve/Etana/excavation_of_gezer_v2/title.pdf|page=131}}</ref>}} |

|||

Traditional pottery, including cooking pots, jugs, mugs and plates that are still hand-made and fired in open, charcoal-fueled kilns as in ancient times in historic villages like [[Jib (village)|al-Jib]] ([[Gibeon]]), Beitin ([[Bethel]]) and Senjel.<ref name=PACE>{{cite web|title=PACE's Exhibit of Traditional Palestinian Handicrafts|publisher=PACE|accessdate=13.07.2007|url=http://www.pace.ps/handi/handi.html}}</ref> |

|||

===Costume and embroidery=== |

===Costume and embroidery=== |

||

{{main|Palestinian costumes}} |

{{main|Palestinian costumes}} |

||

Foreign travelers to [[Palestine]] in late 19th and early 20th centuries often commented on the rich variety of traditional costumes, and particularly among the [[fellaheen]] or village women. |

|||

Until the 1940s, a woman's economic status, whether married or single, and the town or area they were from could be deciphered by most Palestinian women by the type of cloth, colors, cut, and [[embroidery]] motifs, or lack thereof, used for the dress.<ref name=Aramco>{{cite web|title=Woven Legacy, Woven Language|author=Jane Waldron Grutz|publisher=Saudi Aramco World|date=January-February 1991|accessdate=06.04.2007|url=http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199101/woven.legacy.woven.language.htm}}</ref> |

Until the 1940s, a woman's economic status, whether married or single, and the town or area they were from could be deciphered by most Palestinian women by the type of cloth, colors, cut, and [[embroidery]] motifs, or lack thereof, used for the dress.<ref name=Aramco>{{cite web|title=Woven Legacy, Woven Language|author=Jane Waldron Grutz|publisher=Saudi Aramco World|date=January-February 1991|accessdate=06.04.2007|url=http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199101/woven.legacy.woven.language.htm}}</ref> |

||

Though such local and regional variations largely disappeared after the |

Though such local and regional variations largely disappeared after the [[1948 Palestinian exodus]], Palestinian embroidery and costume continue to be produced in new forms and worn alongside Islamic and Western fashions.{{Fact|date=August 2007}} |

||

===Film=== |

===Film=== |

||

| Line 228: | Line 223: | ||

==Ancestry of the Palestinians== |

==Ancestry of the Palestinians== |

||

{{seealso|Palestine}} |

|||

{{seealso|History of Palestine}} |

{{seealso|History of Palestine}} |

||

[[Image:Ramallah-Family-1905.jpg|right|thumb|300px|The Palestinian "Ayoub" family of [[Ghassanids]] ancestry from Ramallah AKA 1905]] |

[[Image:Ramallah-Family-1905.jpg|right|thumb|300px|The Palestinian "Ayoub" family of [[Ghassanids]] ancestry from Ramallah AKA 1905]] |

||

The journalists [[Marcia Kunstel]] and [[Joseph Albright]] write that: <blockquote>"Those who remained in the Jerusalem hills after the Romans expelled the Jews [in the second century A.D.] were a potpourri: farmers and vineyard growers, pagans and converts to Christianity, descendants of the Arabs, Persians, Samaritans, Greeks and old Canaanite tribes."<ref name=Kunstel>{{cite book|title=''Their Promised Land: Arab and Jew in History's Cauldron-One Valley in the Jerusalem Hills''|author=Marcia Kunstel and Joseph Albright|publisher=Crown|year=1990|isbn=0517572311}}</ref></blockquote> According to [[Bernard Lewis]]: <blockquote>"Clearly, in Palestine as elsewhere in the Middle East, the modern inhabitants include among their ancestors those who lived in the country in antiquity. Equally obviously, the demographic mix was greatly modified over the centuries by migration, deportation, immigration, and settlement. This was particularly true in Palestine..."<ref></blockquote>[[Bernard Lewis]], ''Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice'', W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, ISBN 0393318397, p. 49/</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Palestinians, like most other Arabic-speakers, combine ancestries from those who have come to settle the region throughout history; though the precise mixture is a matter of debate, on which [[genetics|genetic]] evidence (see below) has begun to shed some light.<ref name=Nebel2000>{{cite journal|title=High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes |

|||

of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure |

|||

and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews|author=Nebel et al.|publisher=''Human Genetics''|date=2000|volume=107|page=630–641}}<blockquote>"According to historical records part, or perhaps the majority, of the Moslem Arabs in this country descended from local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD (Shaban 1971; Mc Graw Donner 1981). These local inhabitants, in turn, were descendants of the core population that had lived in the area for several centuries, some even since prehistorical times (Gil 1992)... Thus, our findings are in good agreement with the historical record..."</ref> The findings apparently confirm [[Ibn Khaldun]]'s argument that most Arabic-speakers throughout the Arab world descend mainly from [[Cultural assimilation|culturally assimilated]] non-Arabs who are indigenous to their own regions.<ref>[[Ibn Khaldun]], ''The Muqaddimah: an Introduction to History'', Franz Rosenthal, transl. Princeton University Press, 1967, pg. 306</ref> On the subject of Palestinian ancestry, [[Bernard Lewis]] writes: <blockquote>"Clearly, in Palestine as elsewhere in the Middle East, the modern inhabitants include among their ancestors those who lived in the country in antiquity. Equally obviously, the demographic mix was greatly modified over the centuries by migration, deportation, immigration, and settlement. This was particularly true in Palestine..."<ref></blockquote>[[Bernard Lewis]], ''Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice'', W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, ISBN 0393318397, p. 49/</ref></blockquote> |

|||

In the [[Umayyad]] era, increasing conversions to Islam among the local population, together with the immigration of Arabs from Arabia and inland Syria, led to the increased [[Arabization]] of the population. [[Aramaic language|Aramaic]] and [[Greek language|Greek]] were replaced by [[Arabic language|Arabic]] as the area's dominant language.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Griffith|first=Sidney H.|title=From Aramaic to Arabic: The Languages of the Monasteries of Palestine in the Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods|work=Dumbarton Oaks Papers|volume=51|date=1997|pages=13}}</ref> Among the cultural survivals from pre-Islamic times are the significant Palestinian Christian community, and smaller Jewish and [[Samaritan]] ones, as well as an Aramaic and possibly Hebrew [[sub-stratum]] in the local [[Palestinian Arabic|Palestinian Arabic dialect]].<ref>{{cite web|title=The Arabic Language|author=Kees Versteegh|publisher=Edinburgh University|year=2001|isbn=0748614362|url=http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=OHfse3YY6NAC&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=v53WIDmzb2&sig=gEPR0Ooud3oHAT1TN8T8xoZXDUo}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Bedouin]]s of Palestine are said to be more securely known to be [[Arab]] ancestrally as well as by culture; their distinctively conservative [[Varieties of Arabic|dialects]] and pronunciation of ''qaaf'' as ''gaaf'' group them with other [[Bedouin]] across the Arab world and confirm their separate history. [[Arabic language|Arabic]] onomastic elements began to appear in [[Edomite language|Edomite]] inscriptions starting in the 6th century BC, and are nearly universal in the inscriptions of the [[Nabataean]]s, who arrived in today’s Jordan in the 4th-3rd centuries BC.<ref>Healey, 2001, pp. 26-28.</ref> It has thus been suggested that the present day Bedouins of the region may have their origins as early as this period. A few Bedouin are found as far north as [[Galilee]]; however, these seem to be much later arrivals, rather than descendants of the Arabs that [[Sargon II]] settled in [[Samaria]] in [[720s BC|720 BC]]. |

The [[Bedouin]]s of Palestine are said to be more securely known to be [[Arab]] ancestrally as well as by culture; their distinctively conservative [[Varieties of Arabic|dialects]] and pronunciation of ''qaaf'' as ''gaaf'' group them with other [[Bedouin]] across the Arab world and confirm their separate history. [[Arabic language|Arabic]] onomastic elements began to appear in [[Edomite language|Edomite]] inscriptions starting in the 6th century BC, and are nearly universal in the inscriptions of the [[Nabataean]]s, who arrived in today’s Jordan in the 4th-3rd centuries BC.<ref>Healey, 2001, pp. 26-28.</ref> It has thus been suggested that the present day Bedouins of the region may have their origins as early as this period. A few Bedouin are found as far north as [[Galilee]]; however, these seem to be much later arrivals, rather than descendants of the Arabs that [[Sargon II]] settled in [[Samaria]] in [[720s BC|720 BC]]. |

||

The claim that Palestinians are direct descendants of the region's earliest inhabitants, the [[Canaanite]]s, has been put forward by some authors. |

The claim that Palestinians are direct descendants of the region's earliest inhabitants, the [[Canaanite]]s, has been put forward by some authors. According to ''[[Science (journal)|Science]]'', "most Palestinian archaeologists were quick to distance themselves from these ideas,"<ref>Michael Balter, "Palestinians Inherit Riches, but Struggle to Make a Mark" Science, New Series, Vol. 287, No. 5450. (Jan. 7, 2000), pp. 33-34. "'We don't want to repeat the mistakes the Israelis made,' says Moain Sadek, head of the Department of Antiquities's operations in the Gaza Strip. Taha agrees: 'All these controversies about historical rights, who came first and who came second, this is all rooted in ideology. It has nothing to do with archaeology.'"</ref> and in general, historians give little credence to it.<ref>Christison, Kathleen. Review of Marcia Kunstel and Joseph Albright's ''Their Promised Land: Arab and Jew in History's Cauldron-One Valley in the Jerusalem Hills''. ''Journal of Palestine Studies'', Vol. 21, No. 4. (Summer, 1992), pp. 98-100.</ref> Bernard Lewis writes that, "In terms of scholarship, as distinct from politics, there is no evidence whatsoever for the assertion that the Canaanites were Arabs,"<ref name=Lewis>[[Bernard Lewis]], ''Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice'', W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, ISBN 0393318397, p. 49/</ref> and that, "The rewriting of the past is usually undertaken to achieve specific political aims... in bypassing the biblical Israelites and claiming kinship with the Canaanites, the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine, it is possible to assert a historical claim antedating the biblical promise and possession put forward by the Jews."<ref name=Lewis/> |

||

In the journal ''[[Science (journal)|Science]]'', it was reported that "most Palestinian archaeologists were quick to distance themselves from these ideas," and some of those interviewed expressed their view that the issue of who was in Palestine first was an ideological issue that lay outside of the realm of archaeological study.<ref name=Balter>Michael Balter, "Palestinians Inherit Riches, but Struggle to Make a Mark" Science, New Series, Vol. 287, No. 5450. (Jan. 7, 2000), pp. 33-34. "'We don't want to repeat the mistakes the Israelis made,' says Moain Sadek, head of the Department of Antiquities's operations in the Gaza Strip. Taha agrees: 'All these controversies about historical rights, who came first and who came second, this is all rooted in ideology. It has nothing to do with archaeology.'"</ref> Khaled Nashef, the director of the Palestinian Institute for Archaeology, emphasized the importance of developing the nascent Palestinian archaeological school, arguing that, "Archaeology here has concentrated on historical events or figures important to European or Western tradition. This may be important, but it doesn't provide a complete picture of how local people lived here in ancient times."<ref name=Balter/> Bernard Lewis writes that, "In terms of scholarship, as distinct from politics, there is no evidence whatsoever for the assertion that the Canaanites were Arabs,"<ref name=Lewis>[[Bernard Lewis]], ''Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice'', W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, ISBN 0393318397, p. 49/</ref> and that, "The rewriting of the past is usually undertaken to achieve specific political aims... in bypassing the biblical Israelites and claiming kinship with the Canaanites, the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine, it is possible to assert a historical claim antedating the biblical promise and possession put forward by the Jews."<ref name=Lewis/> |

|||

=== DNA clues === |

=== DNA clues === |

||

| ⚫ | Results of a [[DNA]] study by geneticist Ariella Oppenheim matched historical accounts that "some [[Moslem]] [[Arab]]s are descended from [[Christians]] and [[Jews]] who lived in the southern [[Levant]], a region that includes [[Israel]] and the [[Sinai]]. They were descendants of a core population that lived in the area since [[prehistoric]] times."<ref>{{cite web|last=Gibbons|first=Ann|title=Jews and Arabs Share Recent Ancestry|work=ScienceNOW|publisher=American Academy for the Advancement of Science|date=October 30, 2000|url=http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/citation/2000/1030/1}}</ref> |

||

Using new methods in [[genetic genealogy]], scientists and Middle East scholars aim to shed light on key questions about the ancestry of Palestinians and their genetic relation to other demographic groups. |

|||

To track the Palestinian ancestry to a geographic region, geneticists study DNA data for a range of populations in the Middle East. |

|||

| ⚫ | Results of a [[DNA]] study by geneticist Ariella Oppenheim |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Palestinian Arabs and [[Negev Bedouins|Bedouins]] exhibit the highest rates of [[Haplogroup J (Y-DNA)]] (Semino et al., 2004, pp 1029) (55.2% and 65.6% respectively),and the highest frequency of the J1 sub-clade (38.4% and 62.5% respectively) among all groups tested.<ref name=Semino>{{cite journal|title=''Origin, Diffusion and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J''|author=Semino et al.|publisher=American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=74|page=1023-1034|year=2004|url=http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/AJHG/journal/issues/v74n5/40867/40867.web.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

The J1 (or J1-M267) sub-clade is more common throughout the [[Levant]] itself, including [[Syria]], [[Iraq]], and [[Lebanon]] with decreasing frequencies northward to [[Turkey]] and the [[Caucasus]], while J2-M172 (its sister clade) is more abundant in adjacent southern areas such as [[Somalia]], [[Egypt]], and [[Oman]]. <ref name=Flores>{{cite web|title=Isolates in a corridor of migrations: a high-resolution analysis of Y-chromosome variation in Jordan|author=Carlos Flores et al.|publisher=''Human Genetics''|year=2005|url=http://www.homestead.com/wysinger/jordan.pdf}}</ref> Frequency decreases with distance from the [[Levant]] in all directions, reinforcing this region as the most probable origin of its dispersions (Semino et al. 1996; Rosser et al. 2000; Quintana-Murci et al. 2001).<ref name=Flores/> |

|||

In [[genetic genealogy]] studies, Palestinian Arabs were found to have the second-highest rate of [[Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA)]] among Arab groups, behind Bedouins, at 38.4%.<ref>(Semino et al., 2004, pp 1029)</ref> The haplogroup, associated with marker M267, is a marker of the Arab expansion in the early medieval period.<ref name=Semino>{{cite journal|title=''Origin, Diffusion and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J''|author=Semino et al.|publisher=American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=74|page=1023-1034|year=2004|url=http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/resolve?id=doi:10.1086/386295}}</ref> ''(See also J1 Haplogroup frequencies:[http://www.healthanddna.com/JreportY.pdf])'' The haplogroup subclade is most common in the southern [[Levant]], as well as [[Syria]], [[Iraq]], [[Algeria]], and [[Arabia]], while it sharply drops at the border of non-Arab areas like Turkey and Iran. While it is also found in Jewish populations, the related [[Haplogroup J2 (Y-DNA)|haplogroup J2 (M172)]] is more than twice as common in Jews.<ref name=Semino/><ref name=Humangenetics>{{cite journal|title=Y-chromosome Lineages from Portugal, Madeira and Açores Record Elements of Sephardim and Berber Ancestry|author=Rita Gonçalves et al. |

|||

According to Semino et al. (2004), J-M267 (i.e. J1) was brought to [[Northeast Africa]] and [[Europe]] from the Middle East in late [[Neolithic]] times; whereas its presence in the southern part of the Middle East and in [[Northwest Africa]] was brought by a second wave, most likely Arabs who mainly from the 7th century A.D. onward expanded into northern Africa (Nebel et al. 2002).<ref name=Semino/>''(See also J1 Haplogroup frequencies:[http://www.healthanddna.com/JreportY.pdf])'' |

|||

| ⚫ | |publisher=Annals of Human Genetics|volume=69, Issue 4|page=443|date=July 2005|url=www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00161.x}}</ref><ref name=Coffman>{{cite journal|title=A Mosaic of People|author=E. Levy- Coffman|publisher=''Journal of Genetic Genealogy''|year=2005|page=12-33|url=http://www.jogg.info/11/coffman.htm}}</ref><ref name=Cinnioglu>{{cite journal|title=Haplogroup J1-M267 typifies East Africans and Arabian populations|author=Cinnioglu et al.|publisher=Human Genetics|date=29 October 2003|volume=114|page=127–148|url=http://evolutsioon.ut.ee/publications/Cinnioglu2004.pdf}</ref><ref>[http://www.rootsweb.com/~wellsfam/dnaproje/haplogroupJ.html]</ref><ref>[http://www.healthanddna.com/JreportY.pdf]</ref> Th frequency of both J1-M267 and J2-M172 decrease with distance from the [[Levant]] in all directions, reinforcing this region as the most probable origin of its dispersions (Semino et al. 1996; Rosser et al. 2000; Quintana-Murci et al. 2001).<ref name=Flores>{{cite web|title=Isolates in a corridor of migrations: a high-resolution analysis of Y-chromosome variation in Jordan|author=Carlos Flores et al.|publisher=''Human Genetics''|year=2005|url=http://www.homestead.com/wysinger/jordan.pdf}}</ref> |

||

According to a study in the ''European Journal of Human Genetics'', "Arab and other Semitic populations usually possess an excess of J1 Y chromosomes compared to other populations harboring Y-haplogroup J".<ref name=EuroJour>cite journal|title=Paleolithic Y-haplogroup heritage predominates in a Cretan highland plateau|author=Martinez et al.|publisher=''European Journal of Human Genetics''|date=31 January 2007|url=http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v15/n4/abs/5201769a.html}}</ref> |

|||

According to Semino et al. (2004), J-M267 (ie. J1) shows its highest frequencies in the Middle East. It is also found [[Northeast Africa]] and [[Europe]], having spread in late Neolithic times; and during a second-wave in the southern part of the Middle East and in [[Northwest Africa]].<ref name=Semino/> |

|||

| ⚫ | Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA) includes the modal haplotype of the Galilee Arabs (Nebel et al. 2000) and of Moroccan Arabs (Bosch et al. 2001). According to a 2002 study by Nebel et al., on ''Genetic evidence for the expansion of Arabian tribes'', the highest frequency of Eu10 (i.e. J1) (30%–62.5%) has been observed so far in various Moslem Arab populations in the Middle East. (Semino et al. 2000; Nebel et al. 2001).<ref name=Nebel2002>Almut Nebel et Al., Genetic Evidence for the Expansion of Arabian Tribes into the Southern Levant and North Africa, Am J Hum Genet. 2002 June; 70(6): 1594–1596[http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=379148]</ref> |

||

The most frequent Eu10 microsatellite haplotype in NW Africans is identical to a modal haplotype of Moslem Arabs who live in a small area in the north of Israel, the Galilee. (Nebel et al. 2000) termed the modal haplotype of the Galilee (MH Galilee). Interestingly, this modal haplotype is also the most frequent haplotype in the population from the town of Sena, in [[Yemen]] (Thomas et al. 2000). Its single-step neighbor is the most common haplotype of the Yemeni Hadramaut sample (Thomas et al. 2000). The presence of this particular modal haplotype at a significant frequency in three separate geographic locales makes independent genetic-drift events unlikely. The term “Arab,” as well as the presence of Arabs in the Syrian desert and the Fertile Crescent, is first seen in the Assyrian sources from the 9th century bce (Eph'al 1984).<ref>Eph`al I (1984) The Ancient Arabs. The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Kahvihuone.jpg||thumb|right|220px|A coffee house in Palestine, ca [[1900]]]] |

[[Image:Kahvihuone.jpg||thumb|right|220px|A coffee house in Palestine, ca [[1900]]]] |

||

In recent years, many genetic surveys have suggested that, at least paternally, most of the various [[Jewish ethnic divisions]] and the Palestinians — and in some cases other [[Levant]]ines — are genetically closer to each other than the Palestinians to the original Arabs of Arabia or [European] Jews to non-Jewish Europeans.<ref>{{cite web|title=Hereditary inclusion body myopathy: the Middle Eastern genetic cluster|author= Argov et al.|publisher=Department of Neurology and Agnes Ginges Center for Human Neurogenetics, Hadassah University Hospital and Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12743242}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Semitic Genetics|author=Nicholas Wade|publisher=New York Times|url=http://foundationstone.com.au/HtmlSupport/WebPage/semiticGenetics.html}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Orosomucoid (ORM1) polymorphism in Arabs and Jews of Israel: more evidence for a Middle Eastern Origin of the Jews|author=Nevo et al.|publisher=Haifa University|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=8838913}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Jewish Genetics: Abstracts and Summaries|publisher=Kharazaria Info Center|url=http://www.khazaria.com/genetics/abstracts.html}}</ref> Nebel et al. (2001) report that their "recent study of high-resolution microsatellite haplotypes demonstrated that a substantial portion of Y chromosomes of Jews (70%) and of Palestinian Muslim Arabs (82%) belonged to the same chromosome pool (Nebel et al. 2000)."[http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/AJHG/journal/issues/v69n5/013033/013033.web.pdf]<ref>Almut Nebel, The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape of the Middle East, Ann Hum Genet. 2006 Mar;70(2):195-206.[http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/AJHG/journal/issues/v69n5/013033/013033.web.pdf]</ref> |

|||

These studies look at the prevalence of specific [[Polymorphism (biology)|inherited genetic differences]] among populations, which then allow the relatedness of these populations to be determined, and their ancestry to be traced back through [[population genetics]]. These differences can be the cause of [[genetic disease]] or be completely neutral ([[Single nucleotide polymorphism]]). They can be inherited maternally ([[mitochondrial DNA]]), paternally ([[Y chromosome]]), or as a [[genetic recombination|mixture]] from both parents; the results obtained may vary from [[polymorphism]] to polymorphism. |

These studies look at the prevalence of specific [[Polymorphism (biology)|inherited genetic differences]] among populations, which then allow the relatedness of these populations to be determined, and their ancestry to be traced back through [[population genetics]]. These differences can be the cause of [[genetic disease]] or be completely neutral ([[Single nucleotide polymorphism]]). They can be inherited maternally ([[mitochondrial DNA]]), paternally ([[Y chromosome]]), or as a [[genetic recombination|mixture]] from both parents; the results obtained may vary from [[polymorphism]] to polymorphism. |

||

| Line 313: | Line 299: | ||

| quote = |

| quote = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

</ref> In a context of contrast with other Arab populations not mentioned, the African gene types are rarely shared, except among [[Yemenites]], where the average is actually higher at 35%.<ref name = "Richards" /> [[Yemenite Jews]], being a mixture of local Yemenite and Israelite ancestries<ref>{{cite web|title=Jewish Genetics: Abstracts and Summaries|author=Ariella Oppenheim et Michael Hammer|publisher=Khazaria InfoCenter|url=http://www.khazaria.com/genetics/abstracts.html}}</ref>, are also included in the findings for Yemenites, though they average a quarter of the frequency of the non-Jewish Yemenite sample.<ref name = "Richards" /> Other Middle Eastern populations, particularly non-Arabic speakers — [[Turkish people|Turks]], [[Kurds]], [[Armenians]], [[Azeris]], and [[Georgians]] — have few or no such lineages.<ref name = "Richards" /> The findings suggest that gene flow from sub-Saharan Africa has been specifically into Arabic-speaking populations (including at least one Arabic-speaking Jewish population, as indicated in Yemenite Jews), possibly due to the Arab [[slave trade]]. Other [[Mizrahi Jews|Near Eastern Jewish]] groups (whose Arabic-speaking heritage was not indicated by the study) almost entirely lack haplogroups L1–L3A, as is the case with [[Ashkenazi Jews]]. The sub-Saharan African genetic component of [[Ethiopian Jews]] and other African Jewish groups were not contrasted in the study, however, independent studies have shown those Jewish groups to be principally indigenous African in origin. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 13:03, 2 August 2007

Template:Palestinian ethnicity Palestinian people, Palestinians, or Palestinian Arabs are terms used today to refer mainly to Arabic-speaking people with family origins in Palestine. Palestinians are predominantly Sunni Muslims, though there is a significant Christian minority.

Palestinians are represented before the international community by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).[1] The Palestinian National Authority, created as a result of the Oslo Accords is an interim administrative body nominally responsible for governance in Palestinian population centers in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The Palestinian National Charter, as amended by the PLO's Palestine National Council in July 1968, states that "The Palestinians are those Arab nationals who, until 1947, normally resided in Palestine regardless of whether they were evicted from it or stayed there. Anyone born, after that date, of a Palestinian father — whether in Palestine or outside it — is also a Palestinian."[2] It further states that "Jews who had normally resided in Palestine until the beginning of the Zionist invasion are considered Palestinians,"[2] and that the "homeland of Arab Palestinian people" is Palestine, an "indivisible territorial unit" having "the boundaries it had during the British Mandate".[2]

The most recent draft of the Palestinian constitution expands the right of Palestinian citizenship to include all those resident in Palestine before 15 May 1948 and their descendants, specifying that, "This right is transmitted from fathers and mothers to their children ... and endures unless it is given up voluntarily."[3]

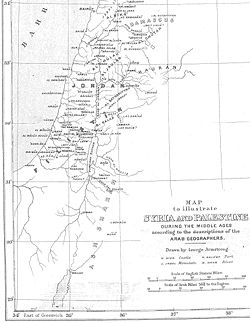

Origins of Palestinian identity

The name of the region known today as Israel, has been known as Filasteen (فلسطين) in Arabic, since the earliest medieval Arab geographers adopted the then-current Greek term Palaestina (Παλαιστινη). Herodotus calls the coast of the Mediterranean Sea running from Phoenicia to Egypt "the coast of Palestine-Syria".[4] This name ultimately was derived from the name of the Philistines (Plishtim) mentioned in the Bible as residing on the Mediterranean coast.

Filasteeni (فلسطيني), meaning Palestinian, was a common adjectival noun (see Arabic grammar) adopted by natives of the region, starting as early as about a hundred years after the Hijra (e.g. `Abdallah b. Muhayriz al-Jumahi al-Filastini,[5] an ascetic who died in the early 700s).

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

| Culture |

| List of Palestinians |

During the British Mandate of Palestine, the term "Palestinian" referred to all people residing there, regardless of religion, and those granted citizenship by the Mandatory authorities were granted "Palestinian citizenship".[6]

Following the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel as the national homeland of the Jewish people, the use and application of the terms "Palestine" and "Palestinian" by and to Palestinian Jews largely dropped from use. The English-language newspaper The Palestine Post for example — which, since 1932, primarily served the Jewish community in the British Mandate of Palestine — changed its name in 1950 to The Jerusalem Post. Today, Jews in Israel and the West Bank generally identify as Israelis. It is common for Arab citizens of Israel to identify themselves as both Israeli and Palestinian and/or Palestinian Arab or Israeli Arab.[7]

The Origins of the Palestinian identity

In his 1997 book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, historian Rashid Khalidi argues that the identity of Palestinians has its roots in nationalist discourses that emerged among the peoples of the Ottoman empire in the late 19th century. Such discourses sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state boundaries in the Middle East after World War I.[8] Khalidi states that the archaeological strata that denote the history of Palestine - encompassing the biblical, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Fatimid, Crusader, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman periods - form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people, as they have come to understand it over the last century.[8][9] He stresses that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive one, with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" continuing to play an important role.[10] Khalidi also states that although the challenge posed by Zionism played a role in shaping this identity, that "it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism."[10]

In contrast, historian James L. Gelvin argues that Palestinian nationalism was a direct reaction to Zionism. In his book The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War he states that “Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement.”[11] Gelvin argues that this fact does not make the Palestinian identity any less legitimate:

The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some "other." Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose.[11]

Whatever the causal mechanism, by the early 20th century trong opposition to Zionism and evidence of a burgeoning nationalistic Palestinian identity is found in the content of Arabic-language newspapers in Palestine, such as Al-Karmil (est. 1908) and Filasteen (est. 1911).[12] Filasteen, published in Jaffa by Issa and Yusef al-Issa, addressed its readers as "Palestinians".[13] The newspaper initially focused its critique of Zionism around the failure of the Ottoman administration to control Jewish immigration and the large influx of foreigners, and later on the impact of Zionist land-purchases on Palestinian peasants (fellaheen), expressing growing concern over land dispossession and its implications for the society at large.[12]

The historical record also gives mixed signals about the interplay between "Arab" and "Palestinian" identities and nationalisms. The idea of a unique Palestinian state separated out from its Arab neighbors was at first rejected by some Palestinian representatives. The First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (in Jerusalem, February 1919), which met for the purpose of selecting a Palestinian Arab representative for the Paris Peace Conference, adopted the following resolution: "We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds."[14] After the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the French conquest of Syria, however, the notion took on greater appeal. In 1920, for instance, the formerly pan-Syrianist mayor of Jerusalem, Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni, said "Now, after the recent events in Damascus, we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria no longer exists. We must defend Palestine".

Similarly, the Second Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (December 1920), passed a resolution calling for an independent Palestine; they then wrote a long letter to the League of Nations about "Palestine, land of Miracles and the supernatural, and the cradle of religions", demanding, amongst other things, that a "National Government be created which shall be responsible to a Parliament elected by the Palestinian People, who existed in Palestine before the war."[citation needed] In 1922, the British authorities over Mandate Palestine proposed a draft constitution which would have granted the Palestinian Arabs representation in a Legislative Council. The Palestine Arab delegation rejected the proposal as "wholly unsatisfactory," noting that "the People of Palestine" could not accept the Balfour Declaration which had been included in the constitution's preamble, as a basis for discussion, and further taking issue with the designation of Palestine as a British "colony of the lowest order."[15] The Arabs tried to get the British to offer an Arab legal establishment again roughly ten years later, but to no avail.[16]

Conflict between Palestinian nationalists and various types of pan-Arabists continued during the British Mandate, but the latter became increasingly marginalised. A prominent leader of the Palestinian nationalists was Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. By 1937, only one of the many Arab political parties in Palestine (the Istiqlal party) promoted political absorption into a greater Arab nation as its main agenda. During World War II, al-Husayni maintained close relations with Nazi officials seeking German support for an independent Palestine.[citation needed] However, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War resulted in those parts of Palestine which were not part of Israel being occupied by Egypt and Jordan.

The Israeli capture of the Gaza Strip and West Bank in the 1967 Six-Day War prompted existing but fractured Palestinian political and militant groups to give up any remaining hope they had placed in pan-Arabism and to rally around the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), (which was founded in 1964), to organize efforts to establish an independent Palestinian state.[17] Mainstream secular Palestinian nationalism was grouped together under the umbrella of the PLO whose constituent organizations include Fateh and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, among others. [18] These groups have also given voice to a tradition that emerged in 1960s that argues that Palestinian nationalism has deep historical roots, with extreme advocates reading a Palestinian nationalist consciousness and identity back into the history of Palestine over the past few centuries, and even millenia, when such consciousness of their identity as Palestinians is in fact relatively modern.[18] From the 1960s onward, consequently, the term "Palestine" was regularly used in political contexts. Various declarations, such as the PLO's 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine, serve to reinforce the Palestinian national identity.

Nevertheless, Palestinian expressions of pan-Arabist sentiment are still be heard from time to time. For example, Zuhayr Muhsin, the leader of the Syrian-funded as-Sa'iqa Palestinian faction and its representative on the PLO Executive Committee, told a Dutch newspaper in 1977 that "There is no difference between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese. It is for political reasons only that we carefully emphasize our Palestinian identity."[citation needed] However, most Palestinian organizations conceived of their struggle as either Palestinian-nationalist or Islamic in nature, and these themes predominate even more today. Within Israel itself, there are political movements, such as Abnaa el-Balad that assert their Palestinian identity, to the exclusion of their Israeli one.

The PLO was recognized as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people by the Arab states in 1974 and was granted observer status as a national liberation movement by the United Nations that same year.[1][19] Israel rejected the resolution, calling it "shameful".[20] In a speech to the Knesset, Deputy Premier and Foreign Minister Allon outlined the government's view that : "No one can expect us to recognize the terrorist organization called the PLO as representing the Palestinians - because it does not. No one can expect us to negotiate with the heads of terror-gangs, who through their ideology and actions, endeavour to liquidate the State of Israel."[20]

Meanwhile, the identity of Palestinians has been a point of contestation with Israel. From 1948 through until the 1980’s, according to Eli Podeh, professor at Hebrew University, the textbooks used in Israeli schools tried to disavow a unique Palestinian identity, referring to "the Arabs of the land of Israel" instead of "Palestinians." Israeli textbooks now widely use the term 'Palestinians.' Podeh believes that Palestinian textbooks of today resemble those from the early years of the Israeli state.[21]

In 1977, the United Nations General Assembly created the "International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People", an annual observance on November 29.[22]

Demographics

In the absence of a comprehensive census including all Palestinian diaspora populations, and those that have remained within what was British Mandate Palestine, exact population figures are difficult to determine.

| Country or region | Population |

|---|---|

| West Bank and Gaza Strip | 3,900,000[23] |

| Jordan | 3,000,000[24] |

| Israel | 1,318,000[25] |

| Syria | 434,896[26] |

| Lebanon | 405,425[26] |

| Chile | 300,000[27] |

| Saudi Arabia | 327,000[25] |

| The Americas | 225,000[28] |

| Egypt | 44,200[28] |

| Other Gulf states | 159,000[25] |

| Other Arab states | 153,000[25] |

| Other countries | 308,000[25] |

| TOTAL | 10,574,521 |

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) announced on October 20, 2004 that the number of Palestinians worldwide at the end of 2003 was 9.6 million, an increase of 800,000 since 2001.[29]

In 2005, a critical review of the PCBS figures and methodology was conducted by the American-Israel Demographic Research Group.[30] In their report,[31] they claimed that several errors in the PCBS methodology and assumptions artificially inflated the numbers by a total of 1.3 million. The PCBS numbers were cross-checked against a variety of other sources (e.g., asserted birth rates based on fertility rate assumptions for a given year were checked against Palestinian Ministry of Health figures as well as Ministry of Education school enrollment figures six years later; immigration numbers were checked against numbers collected at border crossings, etc.). The errors claimed in their analysis included: birth rate errors (308,000), immigration & emigration errors (310,000), failure to account for migration to Israel (105,000), double-counting Jerusalem Arabs (210,000), counting former residents now living abroad (325,000) and other discrepancies (82,000). The results of their research was also presented before the United States House of Representatives on March 8, 2006. [32]

The study was criticised by Sergio DellaPergola, a demographer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[33] DellaPergola accused the authors of misunderstanding basic principles of demography on account of their lack of expertise in the subject. He also accused them of selective use of data and multiple systematic errors in their analysis. For example, DellaPergola claimed that the authors assumed the Palestinian Electoral registry to be complete even though registration is voluntary and good evidence exists of incomplete registration, and similarly that they used an unrealistically low Total Fertility Ratio (a statistical abstraction of births per woman) incorrectly derived from data and then used to reanalyse that data in a "typical circular mistake".

DellaPergola himself estimated the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza at the end of 2005 as 3.33 million, or 3.57 million if East Jerusalem is included. These figures are only slightly lower than the official Palestinian figures.[33]

In Jordan today, there is no official census data that outlines how many of the inhabitants of Jordan are Palestinians, but estimates by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics cite a population range of 50% to 55%. [34][35]

Many Arab Palestinians have settled in the United States, particularly in the Chicago area.[36][37]

In total, an estimated 600,000 Palestinians are thought to reside in the Americas. Arab Palestinian emigration to South America began for economic reasons that pre-dated the Arab-Israeli conflict, but continued to grow thereafter.[38] Many emigrants were from the Bethlehem area. Those emigrating to Latin America were mainly Christian. Half of those of Palestinian origin in Latin America live in Chile. El Salvador[39] and Honduras[40] also have substantial Arab Palestinian populations. These two countries have had presidents of Palestinian ancestry (in El Salvador Antonio Saca, currently serving; in Honduras Carlos Roberto Flores Facusse). Belize, which has a smaller Palestinian population, has a Palestinian minister — Said Musa.[41] Schafik Jorge Handal, Salvadoran politician and former guerrilla leader, was the son of Palestinian immigrants.[4]

Refugees

There are 4,255,120 Palestinians registered as refugees with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). This number includes the descendants of refugees from the 1948 war, but excludes those who have emigrated to areas outside of UNRWA's remit.[26] Therefore, based on these figures, almost half of all Palestinians are registered refugees. Included among them are 993,818 Palestinian refugees of towns and villages inside present-day Israel who currently live in the Gaza Strip and 705,207 Palestinian refugees living in the West Bank.[42] UNRWA figures do not include some 274,000 people, or 1 in 4 of all Arab citizens of Israel, who are internally displaced Palestinian refugees.[43][44]

Religions

The British census of 1922 registered 752,048 inhabitants in Palestine, consisting of 589,177 Palestinian Muslims, 83,790 Palestinian Jews, 71,464 Palestinian Christians (including Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and others) and 7,617 persons belonging to other groups. The corresponding percentage breakdown is 78% Muslim, 11% Jewish, and 9% Christian. Palestinian Bedouin were not counted in the census, but a 1930 British study estimated their number at 70,860.[45]

Currently, no reliable data are available for the worldwide Palestinian population. Bernard Sabella of Bethlehem University estimates that 6% of the Palestinian population is Christian.[46] According to the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza Strip is 97% Muslim and 3% Christian. [47]

All of the Druze living in what was then British Mandate Palestine became Israeli citizens, though some individuals self-identify "Palestinian Druze".[48] According to Salih al-Shaykh, most Druze do not consider themselves to be Palestinian: "their Arab identity emanates in the main from the common language and their socio-cultural background, but is detached from any national political conception. It is not directed at Arab countries or Arab nationality or the Palestinian people, and does not express sharing any fate with them. From this point of view, their identity is Israel, and this identity is stronger than their Arab identity".[49]

There are also about 350 Samaritans who are Palestinian citizens and live in the West Bank.[50]

Jews that identify as Palestinian Jews are rare, but include Israeli Jews who are part of the Neturei Karta group,[51] and Uri Davis, an Israeli citizen and self-described Palestinian Jew who serves as an observer member in the Palestine National Council.[52]

Culture

Palestinian culture is most closely related to the cultures of the nearby Levantine countries such as Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan and of the Arab World. It includes unique art, literature, music, costume and cuisine. Though separated geographically, Palestinian culture continues to survive and flourish in the Palestinian territories, Israel and the Diaspora.

Language

Palestinian Arabic is a subgroup of the broader Levantine Arabic dialect spoken by Palestinians. It has three primary sub-variations with the pronunciation of the qāf serving as a shibboleth to distinguish between the three main Palestinian dialects: In most cities, it is a glottal stop; in smaller villages and the countryside, it is a pharyngealized k; and in the far south, it is a g, as among Bedouin speakers. In a number of villages in the Galilee (e.g. Maghār), and particularly, though not exclusively among the Druze, the qāf is actually pronounced qāf as in Classical Arabic.

Barbara McKean Parmenter has noted that the Arabs of Palestine have been credited with the preservation of the indigenous Semitic place names for many sites mentioned in the Bible which were documented by the American archaeologist Edward Robinson in the early 20th century.[53]

Literature

The long history of the Arabic language and its rich written and oral tradition form part of the Palestinian literary tradition as it has developed over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries.[citation needed]

Poetry

Poetry, using classical pre-Islamic forms, remains an extremely popular art form, often attracting Palestinian audiences in the thousands. Until 20 years ago, local folk bards reciting traditional verses were a feature of every Palestinian town.[54]

After the 1948 Palestinian exodus, poetry was transformed into a vehicle for political activism. From among those Palestinians who became Arab citizens of Israel after the passage of the Citizenship Law in 1952, a school of resistance poetry was born that included poets like Mahmoud Darwish, Samih al-Qasim, and Tawfiq Zayyad.[54]

The work of these poets was largely unknown to the wider Arab world for years because of the lack of diplomatic relations between Israel and Arab governments. The situation changed after Ghassan Kanafani, another Palestinian writer in exile in Lebanon published an anthology of their work in 1966.[54]

Palestinian poets often write about the common theme of a strong affection and sense of loss and longing for a lost homeland.[54]

Folk tales

Traditional storytelling among Palestinians is prefaced with an invitation to the listeners to give blessings to God and the Prophet Mohammed or the Virgin Mary as the case may be, and includes the traditional opening: "There was, or there was not, in the oldness of time ..."[54]

Formulaic elements of the stories share much in common with the wider Arab world, though the rhyming scheme is distinct. There are a cast of supernatural characters: djinns who can cross the Seven Seas in an instant, giants, and ghouls with eyes of ember and teeth of brass. Stories invariably have a happy ending, and the storyteller will usually finish off with a rhyme like: "The bird has taken flight, God bless you tonight," or "Tutu, tutu, finished is my haduttu (story)."[54]

Intellectuals

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, Palestinian intellectuals were integral parts of wider Arab intellectual circles, as represented by individuals such as May Ziade and Khalil Beidas.

Diaspora figures like Edward Said and Ghada Karmi, Arab citizens of Israel like Emile Habibi, refugee camp residents like Ibrahim Nasrallah have made contributions to a number of fields, exemplifying the diversity of experience and thought among Palestinians.

Music

Palestinian music is well-known and respected throughout the Arab world. A new wave of performers emerged with distinctively Palestinian themes following the 1948 Palestinian exodus, relating to the dreams of statehood and the burgeoning nationalist sentiments. A traditional folk dance, the dabke, is still danced at Palestinian weddings.[citation needed]

Cuisine

Palestinian cuisine is divided into two groups: In the Galilee and northern West Bank the cuisine is similar to that of Lebanon and Syria while other parts of the West Bank, such as the Jerusalem, and the Hebron region, locals have a heavy cooking style of their own. Gaza is more likely to be piquant, incorporating fresh green or dried red hot peppers, reflecting the culinary influences of Egypt.

Mezze describes an assortment of dishes laid out on the table for a meal that takes place over several hours, a characteristic common to Mediterranean cultures. One of the primary mezze dishes is hummus. Hummus u ful is another type of hummus dish cooked in a similar way except it is mixed in with boiled and ground fava beans. Tabouleh is a favourite type of salad.

Other common mezze dishes include baba ghanoush, labaneh, and zate u zaatar which is the pita bread dipping of olive oil and ground thyme and sesame seeds. Kebbiyeh or kubbeh is another popular dish made of minced meat enclosed in a case of burghul (cracked wheat) and deep fried.

Famous entrées in Palestine are waraq al-'inib - boiled grape leaves wrapped around cooked rice and lamb pieces. One of the most distinctive Palestinian dishes, said to originate in the Northern West Bank, near Jenin and Tulkarem, is musakhan - roasted chicken smothered in fried onions, pine nuts, and sumac (a dark red, lemony flavored spice), and laid over taboon..

Lamb leg in a thick and cooked goat milk yogurt, laban, is also common as is imhamar, a dish of roasted chicken and potatoes in a thick sauce of diced chili peppers and onions.

Art

Similar to the structure of Palestinian society, the Palestinian art field extends over four main geographic centers: 1) the West Bank and Gaza Strip 2) Israel 3) the Palestinian diaspora in the Arab world, and 4) the Palestinian diaspora in Europe and the United States.[55]

Contemporary Palestinian art finds its roots in folk art and traditional Christian and Islamic painting popular in Palestine over the ages. After the 1948 Palestinian exodus, nationalistic themes have predominated as Palestinian artists use diverse media to express and explore their connection to identity and land.[56]

Pottery

Modern pots, bowls, jugs and cups produced by Palestinians, particularly those produced prior to the 1940s, are similar in shape, fabric and decoration to their ancient equivalents.[57] Cooking pots, jugs, mugs and plates that are still hand-made and fired in open, charcoal-fuelled kilns as in ancient times in historic villages like al-Jib (Gibeon), Beitin (Bethel) and Senjel.[58]

Costume and embroidery

Until the 1940s, a woman's economic status, whether married or single, and the town or area they were from could be deciphered by most Palestinian women by the type of cloth, colors, cut, and embroidery motifs, or lack thereof, used for the dress.[59]

Though such local and regional variations largely disappeared after the 1948 Palestinian exodus, Palestinian embroidery and costume continue to be produced in new forms and worn alongside Islamic and Western fashions.[citation needed]

Film

Palestinian cinema is relatively young in comparison to Arab cinema as a whole, many Palestinian movies are made with European and Israeli funding and support.[5] Palestinian movies are not exclusively produced in Arabic and some are made in English, French and Hebrew.[6]

It is believed that there have been over 800 films produced about Palestinians, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and other related topics.[7]

Ancestry of the Palestinians

The journalists Marcia Kunstel and Joseph Albright write that:

"Those who remained in the Jerusalem hills after the Romans expelled the Jews [in the second century A.D.] were a potpourri: farmers and vineyard growers, pagans and converts to Christianity, descendants of the Arabs, Persians, Samaritans, Greeks and old Canaanite tribes."[60]

According to Bernard Lewis:

"Clearly, in Palestine as elsewhere in the Middle East, the modern inhabitants include among their ancestors those who lived in the country in antiquity. Equally obviously, the demographic mix was greatly modified over the centuries by migration, deportation, immigration, and settlement. This was particularly true in Palestine..."[61]

In the Umayyad era, increasing conversions to Islam among the local population, together with the immigration of Arabs from Arabia and inland Syria, led to the increased Arabization of the population. Aramaic and Greek were replaced by Arabic as the area's dominant language.[62] Among the cultural survivals from pre-Islamic times are the significant Palestinian Christian community, and smaller Jewish and Samaritan ones, as well as an Aramaic and possibly Hebrew sub-stratum in the local Palestinian Arabic dialect.[63]

The Bedouins of Palestine are said to be more securely known to be Arab ancestrally as well as by culture; their distinctively conservative dialects and pronunciation of qaaf as gaaf group them with other Bedouin across the Arab world and confirm their separate history. Arabic onomastic elements began to appear in Edomite inscriptions starting in the 6th century BC, and are nearly universal in the inscriptions of the Nabataeans, who arrived in today’s Jordan in the 4th-3rd centuries BC.[64] It has thus been suggested that the present day Bedouins of the region may have their origins as early as this period. A few Bedouin are found as far north as Galilee; however, these seem to be much later arrivals, rather than descendants of the Arabs that Sargon II settled in Samaria in 720 BC.

The claim that Palestinians are direct descendants of the region's earliest inhabitants, the Canaanites, has been put forward by some authors. According to Science, "most Palestinian archaeologists were quick to distance themselves from these ideas,"[65] and in general, historians give little credence to it.[66] Bernard Lewis writes that, "In terms of scholarship, as distinct from politics, there is no evidence whatsoever for the assertion that the Canaanites were Arabs,"[67] and that, "The rewriting of the past is usually undertaken to achieve specific political aims... in bypassing the biblical Israelites and claiming kinship with the Canaanites, the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine, it is possible to assert a historical claim antedating the biblical promise and possession put forward by the Jews."[67]

DNA clues

Results of a DNA study by geneticist Ariella Oppenheim matched historical accounts that "some Moslem Arabs are descended from Christians and Jews who lived in the southern Levant, a region that includes Israel and the Sinai. They were descendants of a core population that lived in the area since prehistoric times."[68]

In genetic genealogy studies, Palestinian Arabs were found to have the second-highest rate of Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA) among Arab groups, behind Bedouins, at 38.4%.[69] The haplogroup, associated with marker M267, is a marker of the Arab expansion in the early medieval period.[70] (See also J1 Haplogroup frequencies:[8]) The haplogroup subclade is most common in the southern Levant, as well as Syria, Iraq, Algeria, and Arabia, while it sharply drops at the border of non-Arab areas like Turkey and Iran. While it is also found in Jewish populations, the related haplogroup J2 (M172) is more than twice as common in Jews.[70][71][72][73][74][75] Th frequency of both J1-M267 and J2-M172 decrease with distance from the Levant in all directions, reinforcing this region as the most probable origin of its dispersions (Semino et al. 1996; Rosser et al. 2000; Quintana-Murci et al. 2001).[76]

According to a study in the European Journal of Human Genetics, "Arab and other Semitic populations usually possess an excess of J1 Y chromosomes compared to other populations harboring Y-haplogroup J".[77] According to Semino et al. (2004), J-M267 (ie. J1) shows its highest frequencies in the Middle East. It is also found Northeast Africa and Europe, having spread in late Neolithic times; and during a second-wave in the southern part of the Middle East and in Northwest Africa.[70]

Haplogroup J1 (Y-DNA) includes the modal haplotype of the Galilee Arabs (Nebel et al. 2000) and of Moroccan Arabs (Bosch et al. 2001). According to a 2002 study by Nebel et al., on Genetic evidence for the expansion of Arabian tribes, the highest frequency of Eu10 (i.e. J1) (30%–62.5%) has been observed so far in various Moslem Arab populations in the Middle East. (Semino et al. 2000; Nebel et al. 2001).[78] The most frequent Eu10 microsatellite haplotype in NW Africans is identical to a modal haplotype of Moslem Arabs who live in a small area in the north of Israel, the Galilee. (Nebel et al. 2000) termed the modal haplotype of the Galilee (MH Galilee). Interestingly, this modal haplotype is also the most frequent haplotype in the population from the town of Sena, in Yemen (Thomas et al. 2000). Its single-step neighbor is the most common haplotype of the Yemeni Hadramaut sample (Thomas et al. 2000). The presence of this particular modal haplotype at a significant frequency in three separate geographic locales makes independent genetic-drift events unlikely. The term “Arab,” as well as the presence of Arabs in the Syrian desert and the Fertile Crescent, is first seen in the Assyrian sources from the 9th century bce (Eph'al 1984).[79]

In recent years, many genetic surveys have suggested that, at least paternally, most of the various Jewish ethnic divisions and the Palestinians — and in some cases other Levantines — are genetically closer to each other than the Palestinians to the original Arabs of Arabia or [European] Jews to non-Jewish Europeans.[80][81][82][83] Nebel et al. (2001) report that their "recent study of high-resolution microsatellite haplotypes demonstrated that a substantial portion of Y chromosomes of Jews (70%) and of Palestinian Muslim Arabs (82%) belonged to the same chromosome pool (Nebel et al. 2000)."[9][84]

These studies look at the prevalence of specific inherited genetic differences among populations, which then allow the relatedness of these populations to be determined, and their ancestry to be traced back through population genetics. These differences can be the cause of genetic disease or be completely neutral (Single nucleotide polymorphism). They can be inherited maternally (mitochondrial DNA), paternally (Y chromosome), or as a mixture from both parents; the results obtained may vary from polymorphism to polymorphism.

One study on congenital deafness identified an allele only found in Palestinian and Ashkenazi communities, suggesting a common origin.[85] An investigation[86] of a Y-chromosome polymorphism found Lebanese, Palestinian, and Sephardic populations to be particularly closely related; a third study [10], looking at Human leukocyte antigen differences among a broad range of populations, found Palestinians to be particularly closely related to Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi Jews, as well as Middle-Eastern and Mediterranean populations.

One point in which Palestinians and Ashkenazi Jews and most Near Eastern Jewish communities appear to contrast is in the proportion of sub-Saharan African gene types which have entered their gene pools. One study found that Palestinians and some other Arabic-speaking populations — Jordanians, Syrians, Iraqis, and Bedouins — have what appears to be substantial gene flow from sub-Saharan Africa, amounting to 10-15% of lineages within the past three millennia.[87] In a context of contrast with other Arab populations not mentioned, the African gene types are rarely shared, except among Yemenites, where the average is actually higher at 35%.[87] Yemenite Jews, being a mixture of local Yemenite and Israelite ancestries[88], are also included in the findings for Yemenites, though they average a quarter of the frequency of the non-Jewish Yemenite sample.[87] Other Middle Eastern populations, particularly non-Arabic speakers — Turks, Kurds, Armenians, Azeris, and Georgians — have few or no such lineages.[87] The findings suggest that gene flow from sub-Saharan Africa has been specifically into Arabic-speaking populations (including at least one Arabic-speaking Jewish population, as indicated in Yemenite Jews), possibly due to the Arab slave trade. Other Near Eastern Jewish groups (whose Arabic-speaking heritage was not indicated by the study) almost entirely lack haplogroups L1–L3A, as is the case with Ashkenazi Jews. The sub-Saharan African genetic component of Ethiopian Jews and other African Jewish groups were not contrasted in the study, however, independent studies have shown those Jewish groups to be principally indigenous African in origin.

See also

- Arab–Israeli conflict

- Mandate for Palestine

- Definitions of "Palestine" and "Palestinian"

- Palestinian Jews

- List of famous Palestinians

- Palestinian Arabic

- Palestinian economy

- Palestinian exodus

- Palestinian music

- Palestinian costumes

- Palestinian Christian

- Palestinian refugees

- Arab diaspora

- Palestinian Chilean

- Palestinian Nicaraguan

- Islam in Honduras

- PLO

- Hamas

- Palestinian National Authority

- International aid to Palestinians

- Palestinian territories

Footnotes

- ^ a b "Who Represents the Palestinians Officially Before the World Community?". Institute for Middle East Understanding. 2006 - 2007. Retrieved 07.27.2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b c "The Palestinian National Charter". Permanent Observer Mission of Palestine to the United Nations.

- ^ "Full Text of Palestinian Draft Constitution". Kokhaviv Publications.

{{cite web}}: Text "author-Palestine National Council" ignored (help) - ^ http://classics.mit.edu/Herodotus/history.4.iv.html

- ^ Michael Lecker. "On the burial of martyrs". Tokyo University.

- ^ Government of the United Kingdom (December 31, 1930). "REPORT by His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of PALESTINE AND TRANS-JORDAN FOR THE YEAR 1930". League of Nations. Retrieved 2007-05-29.