St. Augustine, Florida: Difference between revisions

→Education: add info on FSDB and St. Joe Academy |

|||

| Line 292: | Line 292: | ||

* [http://www.drbronsontours.com Dr. Bronson's St. Augustine History] |

* [http://www.drbronsontours.com Dr. Bronson's St. Augustine History] |

||

* [http://www.staugustinelinks.com/slideshow/st-augustine-historical-postcards.asp Historical Postcards of Old St. Augustine] |

* [http://www.staugustinelinks.com/slideshow/st-augustine-historical-postcards.asp Historical Postcards of Old St. Augustine] |

||

* [http://www.augustine.com/history/ St. Augustine history including general history, black history, online books and more.] |

|||

===Higher education=== |

===Higher education=== |

||

Revision as of 16:28, 26 November 2008

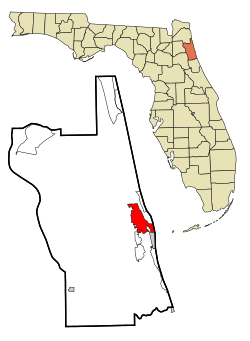

St. Augustine, Florida in Florida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): Ancient City, Continental United States' Oldest City | |

Location in St. Johns County and the state of Florida | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | St. Johns |

| Established | 1565 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joseph L. Boles |

| Area | |

| • City | 10.7 sq mi (27.8 km2) |

| • Land | 2.4 sq mi (21.7 km2) |

| • Water | 2.4 sq mi (6.1 km2) 21.99% |

| Elevation | 4.99 ft (1.52 m) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • City | 12,284 |

| • Density | 1,385/sq mi (534.7/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,277,997 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Website | http://www.staugustinegovernment.com/ |

Template:FixHTML St. Augustine is the county seat of St. Johns County Template:GR, Florida, in the United States. It is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city, and the oldest port, in the continental United States.[1] St. Augustine lies in a region of Florida known as The First Coast, which extends from Amelia Island in the north, south to Jacksonville, St. Augustine and Palm Coast. According to the 2000 census, the city population was 11,592; in 2004, the population estimated by the U.S. Census Bureau was 12,157.[2]

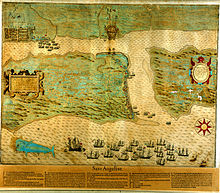

History

St. Augustine was founded by the Spanish under Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in 1565.[1] The first Christian worship service held in a permanent settlement in the continental United States was a Catholic Mass celebrated in St. Augustine. A few settlements were founded prior to St. Augustine but all failed, including the original Pensacola colony in West Florida, founded by Tristán de Luna y Arellano in 1559, with the area abandoned in 1561 due to hurricanes, famine and warring tribes. Fort Caroline, founded by the French in 1564 in what is today Jacksonville, Florida only lasted a year before being obliterated by the Spanish in 1565.

Spanish rule

The city of St. Augustine was founded by Pedro Menéndez on September 8, 1565. Menéndez first sighted land on August 28, the feast day of Augustine of Hippo, and consequently named the settlement San Augustíne. Martín de Argüelles was born there one year later in 1566, the first child of European ancestry to be born in what is now the continental United States. This came 21 years before the English settlement at Roanoke Island in Virginia Colony, and 42 years before the successful settlements of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Jamestown, Virginia. In all the territory under the jurisdiction of the United States, only European-established settlements in Puerto Rico are older than St. Augustine, with the oldest being Caparra, founded in 1508, whose inhabitants relocated and founded San Juan, in 1521.

In 1586 St. Augustine was attacked and burned by English privateer Sir Francis Drake. In 1668 it was plundered by pirates and most of the inhabitants were killed. In 1702 and 1740 it was unsuccessfully attacked by British forces from their new colonies in the Carolinas and Georgia. The most serious of these came in the latter year, when James Oglethorpe of Georgia allied himself with Ahaya the Cowkeeper, chief of the Alachua band of the Seminole tribe and conducted the Siege of St. Augustine during the War of Jenkin's Ear.

British rule

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris ended the French and Indian War and gave Florida and St. Augustine to the British, an acquisition the British had been unable to take by force and keep due to the strong fort there. St. Augustine came under British rule and served as a Loyalist colony during the American Revolutionary War. The Treaty of Paris in 1783 gave the American colonies north of Florida their independence, and ceded Florida to Spain in recognition of Spanish efforts on behalf of the American colonies during the war.

American rule

Florida was under Spanish control again from 1784 to 1821. During this time, Spain was being invaded by Napoleon and was struggling to retain its colonies. Florida no longer held its past importance to Spain. The expanding United States, however, regarded Florida as vital to its interests. In 1821, the Adams-Onís Treaty peaceably turned the Spanish colonies in Florida and, with them, St. Augustine, over to the United States.

Florida was a United States territory until 1845 when it became a U.S. state. In 1861, the American Civil War began and Florida seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy. Days before Florida seceded, state troops took the fort at St. Augustine from a small Union garrison (one soldier) on January 7, 1861. However, federal troops loyal to the United States government reoccupied the city on March 11, 1862 and remained in control throughout the four-year-long war. In 1865, Florida rejoined the United States.

Spanish Colonial era buildings still existing in the city include the fortress Castillo de San Marcos. The fortress successfully repelled the British attacks of the 18th century, served as a prison for the Native American leader Osceola in 1837, and was occupied by Union troops during the American Civil War. It was removed from the Army's active duty rolls in 1900 after 205 years of service under five different flags. It is now the Castillo de San Marcos National Monument.

From Flagler to the present

In the late 19th century the railroad came to town, and led by northeastern industrialist Henry Flagler, St. Augustine became a winter resort for the very wealthy. A number of mansions and palatial grand hotels of this era still exist, some converted to other use, such as housing parts of Flagler College and museums. Flagler went on to develop much more of Florida's east coast, including his Florida East Coast Railway which eventually reached Key West in 1912.

The city is a popular tourist attraction, for the rich Spanish Colonial Revival Style architectural heritage as well as elite 19th century architecture. In 1938 the theme park Marineland opened just south of St. Augustine, becoming one of Florida's first themed parks and setting the stage for the development of this industry in the following decades. The city is also one terminus of the Old Spanish Trail, which in the 1920s linked St. Augustine to San Diego, California with 3000 miles of roadways.

Civil Rights movement

In addition to being a national tourist destination and the continental United States' oldest city settled by Europeans, St. Augustine was also a pivotal site for the civil rights movement in 1963[3] and 1964.

Despite the 1954 Supreme Court act in Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled that the "separate but equal" legal status of public schools made those schools inherently unequal, St. Augustine still had only 6 black children admitted into white schools. The homes of two of the families of these children were burned by local segregationists while other families were forced to move out of the county because the parents were fired from their jobs and could find no work.

In 1963 a sit-in protest at a local diner ended in the arrest and imprisonment of 16 young black protestors and 7 juveniles. Four of the children, two of whom were 16 year old girls, were sent to “reform” school and retained for 6 months.[4]

In September 1963, the Ku Klux Klan staged a rally of several hundred Klansmen on the outskirts of town. They seized NAACP leader and local dentist Robert Hayling and three other NAACP activists who they beat with fists, chains, and clubs. The four men were rescued by Highway Patrol officers. St. Johns County Sheriff L. O. Davis arrested four white men for the beating and also arrested the four unarmed blacks for "assaulting" the large crowd of armed Klansmen. Charges against the Klansmen were dismissed, but Hayling was convicted of "criminal assault" against the KKK mob. In the summer of 1964 a massive non-violent direct action campaign was led by Hayling, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, Dorothy Cotton and other major civil rights leaders intent on changing the conditions of blacks in St. Augustine.[5]

From May until July 1964 protesters endured abuse, beatings, and verbal assaults without any retaliation. By absorbing the violence and hate instead of striking back the protesters gained national sympathy and, it is thought, were a key factor in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The movement engaged in nightly marches down King Street. The protesters were met by white segregationists who violently assaulted them. Hundreds of the marchers were arrested and incarcerated. The jail was filled, so subsequent detainees were kept in an uncovered stockade in the hot sun.

When attempts were made to integrate the beaches of Anastasia Island, demonstrators were beaten and driven into the water by police and segregationists. Some of the protesters could not swim and had to be saved from possible drowning by other demonstrators.[citation needed]

The demonstrations came to a climax when a group of black and white protesters jumped into the swimming pool at the Monson Motor Lodge, an entirely white hotel where several other protests had been held. In response to the protest the owner of the hotel, James Brock, who was a usually shy and passive man, was photographed pouring muriatic acid into the pool to get the protesters out. Photographs of this, and of a policeman jumping into the pool to arrest them, were broadcast around the world and became some of the most famous images of the entire civil rights movement. The motel and pool were demolished in March, 2003, eliminating a symbol of the Civil Rights Movement.[6]

Hurricanes

In modern times, St. Augustine has mostly been spared the wrath of tropical cyclones. The only direct hit was Hurricane Dora, which came ashore just after midnight on September 10, 1964. Prior to Dora, no hurricane had struck northeast Florida from the east since record-keeping began in 1851.[7]

Geography and climate

St. Augustine is located at 29°53′39″N 81°18′48″W / 29.89417°N 81.31333°WInvalid arguments have been passed to the {{#coordinates:}} function (29.89785, -81.31151)Template:GR. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.7 square miles (27.8 km²), of which, 8.4 square miles (21.7 km²) of it is land and 2.4 square miles (6.1 km²) of it (21.99%) is water. Access to the Atlantic Ocean is via the St. Augustine Inlet of the Matanzas River.

Demographics

As of the 2000 United States Census,Template:GR there were 11,592 people, 4,963 households, and 2,600 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,384.6 people per square mile (534.7/km²). There were 5,642 housing units at an average density of 673.9/sq mi (260.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 81.21% White, 15.07% African American, 0.41% Native American, 0.72% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 0.88% from other races, and 1.61% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.11% of the population.

There were 4,963 households out of which 18.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.4% were married couples living together, 12.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 47.6% were non-families. 36.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.11 and the average family size was 2.76.

In the city the population was spread out with 16.1% under the age of 18, 15.3% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 25.2% from 45 to 64, and 19.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females there were 84.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,358, and the median income for a family was $41,892. Males had a median income of $27,099 versus $25,121 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,225. About 9.8% of families and 15.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.8% of those under age 18 and 10.0% of those age 65 or over.

Points of interest

- Alligator Farm

- Anastasia State Park

- Bridge of Lions

- Casa Monica Hotel

- Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

- Cathedral of St. Augustine

- Flagler College, part of which is the former Ponce de León Hotel

- Fort Matanzas National Monument

- Florida School for the Deaf and Blind

- Fort Mose Historic State Park

- Fountain of Youth

- Gonzalez-Alvarez House (Oldest House)

- Grace United Methodist Church

- Lightner Museum, in the former Hotel Alcazar

- Old St. Johns County Jail

- Oldest Wooden Schoolhouse

- Ripley's Believe it or Not! Museum

- The Spanish Military Hospital Museum

- St. Augustine Airport FAA code is: SGJ

- St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum

- St. Augustine Amphitheatre

- World Golf Hall of Fame & IMAX Theater at World Golf Village

- Zorayda Castle

Sister cities

Education

- St. Johns County School District operates local public schools

- Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind, a public residential school operated by the state of Florida, was founded in 1885 and is located in St. Augustine[8]

- St. Joseph Academy, founded in 1866, is the oldest Catholic high school in Florida

Notable residents

- Jim Albrecht, World Series Of Poker Tournament Director, Commentator and Film Consultant

- Murray Armstrong, 5-time NCAA champion hockey coach

- Richard Boone, actor

- Willie Galimore, football player

- Richard Henry Pratt, soldier and educator

- Ray Charles, pianist

- Henry Flagler, industrialist

- Lindy Infante, professional football coach

- Stetson Kennedy, Author

- Scott Lagasse Jr., NASCAR racer

- Johnny Mize, baseball player

- Prince Achille Murat, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte

- Chief Osceola, Seminole Indian Chief (held prisoner at Fort Marion, now Castillo de San Marcos)

- Scott Player, Punter NFL

- Tom Petty, rock musician

- Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, novelist

- Steve Spurrier, College/Pro Football coach

- Edmund Kirby Smith, General

- William W. Loring, General

- Travis Tomko, Pro Wrestler

- Tim Tebow, College football player

- Howell W. Melton, United States District Judge

- Howell W. Melton Jr., Managing Partner of Holland & Knight

References

- ^ a b National Historic Landmarks Program - St. Augustine Town Plan Historic District

- ^ Table 4: Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places in Florida, Listed Alphabetically: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2004

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Veterans. "St. Augustine FL, Movement — 1963".

- ^ United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965. Law Enforcement: A Report on Equal Protection in the South. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, p. 47.

- ^ St. Augustine FL Movement — 1964 ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ St. Augustine Record: March 18, 2003-Demolition begins on Monson Inn by Ken Lewis

- ^ National Hurricane Center. Hurricane Database

- ^ Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind website

Additional Reading

- Abbad y Lasierra, Iñigo, "Relación del descubrimiento, conquista y población de las provincias y costas de la Florida" - "Relación de La Florida" (1785); edición de Juan José Nieto Callén y José María Sánchez Molledo.

- Fairbanks, George R. (George Rainsford), "History and antiquities of St. Augustine, Florida" (1881), Jacksonville, Fla., H. Drew.

- Reynolds, Charles B. (Charles Bingham), "Old Saint Augustine, a story of three centuries", (1893) St. Augustine, Fla. E. H. Reynolds.

- United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965. Law Enforcement: A Report on Equal Protection in the South. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Images

- St. Augustine Pics Daily pictures of St. Augustine, Florida.

- Twine Collection Over 100 images of the St. Augustine community of Lincolnville between 1922 and 1927. From the State Library & Archives of Florida.

External links

Government resources

Historical

- St. Augustine Movement 1963-1964 ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- King Encyclopedia

- Castillo de San Marcos Website, US National Park Service

- St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum

- Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP) Maritime archaeology in America's oldest port

- St. Augustine's place in the Civil Rights movement

- Dr. Bronson's St. Augustine History

- Historical Postcards of Old St. Augustine

- St. Augustine history including general history, black history, online books and more.