Zheng He: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 68.156.95.225 (talk) to last version by Ja 62 |

Info removed due to inaccurate mistakes. The size of the Treasure ships have been confirmed to be over 400 feet in length at least, due to the discoveries of giantic sized rudders found in China |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

[[Image:FraMauro1420Ship.png|thumb|Detail of the [[Fra Mauro map]] relating the travels of a [[Junk (sailing)|junk]] into the Atlantic Ocean in 1420. The ship also is illustrated above the text.]] |

[[Image:FraMauro1420Ship.png|thumb|Detail of the [[Fra Mauro map]] relating the travels of a [[Junk (sailing)|junk]] into the Atlantic Ocean in 1420. The ship also is illustrated above the text.]] |

||

There are speculations that some of Zheng's ships may have traveled beyond the [[Cape of Good Hope]]. In particular, the [[Venice|Venetian]] monk and cartographer [[Fra Mauro]] describes in his 1459 [[Fra Mauro map]] the travels of a huge "[[junk (ship)|junk]] from India" 2,000 miles into the [[Atlantic Ocean]] in 1420. What Fra Mauro meant by 'India' is not known and some scholars believe he meant an Arab ship.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.henry-davis.com/MAPS/LMwebpages/249mono.html|title=Slide #249 Monograph|publisher=Henry-davis.com|accessdate=2008-09-01}}</ref> |

There are speculations that some of Zheng's ships may have traveled beyond the [[Cape of Good Hope]]. In particular, the [[Venice|Venetian]] monk and cartographer [[Fra Mauro]] describes in his 1459 [[Fra Mauro map]] the travels of a huge "[[junk (ship)|junk]] from India" 2,000 miles into the [[Atlantic Ocean]] in 1420. What Fra Mauro meant by 'India' is not known and some scholars believe he meant an Arab ship.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.henry-davis.com/MAPS/LMwebpages/249mono.html|title=Slide #249 Monograph|publisher=Henry-davis.com|accessdate=2008-09-01}}</ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.1421exposed.com/html/heresy.html |title=Heresy|publisher=1421exposed.com|accessdate=2008-09-01}}</ref> |

||

Zheng himself wrote of his travels: |

Zheng himself wrote of his travels: |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

== Size of the ships == |

== Size of the ships == |

||

Traditional and popular accounts of Zheng He's voyages have described a great fleet of gigantic ships, far larger than any other wooden ships in history. Most modern scholars consider these descriptions to |

Traditional and popular accounts of Zheng He's voyages have described a great fleet of gigantic ships, far larger than any other wooden ships in history. Most modern scholars consider these descriptions relatively accurate due to the fact that recent archaeological finds have revealed gigantic ship rudders in the old Ming dynasty shipbuilding facility in [[Nanjing]]. |

||

Chinese records {{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} assert that Zheng He's fleet sailed as far as East Africa. According to medieval Chinese sources {{Citation needed|date=October 2009}}, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships.<ref>Dreyer (2006): 122–124</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_focus/2005-07/05/content_70352.htm |title=Briton charts Zheng He's course across globe |publisher=Chinaculture.org |date= |accessdate=2009-07-23}}</ref> The fleet included: |

Chinese records {{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} assert that Zheng He's fleet sailed as far as East Africa. According to medieval Chinese sources {{Citation needed|date=October 2009}}, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships.<ref>Dreyer (2006): 122–124</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_focus/2005-07/05/content_70352.htm |title=Briton charts Zheng He's course across globe |publisher=Chinaculture.org |date= |accessdate=2009-07-23}}</ref> The fleet included: |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

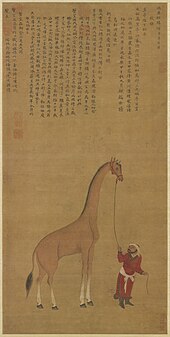

[[Image:ShenDuGiraffePainting.jpg|thumb|left|upright|A [[giraffe]] brought from [[Somalia]]<ref>Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", ''Natural History'' Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 [http://muweb.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/art/WILSON09.ART]</ref> in the [[1415|twelfth year of Yongle (AD 1415)]].]] |

[[Image:ShenDuGiraffePainting.jpg|thumb|left|upright|A [[giraffe]] brought from [[Somalia]]<ref>Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", ''Natural History'' Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 [http://muweb.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/art/WILSON09.ART]</ref> in the [[1415|twelfth year of Yongle (AD 1415)]].]] |

||

Zheng He's initial objective was {{Citation needed|date=October 2009}}to enroll |

Under the Emperor's patronage and direct imperial decree, Zheng He's initial objective was {{Citation needed|date=October 2009}}to enroll all the countries of the world into the Ming [[Tribute|tributary]] system, but after the death of the emperor, due to a power struggle between the eunuchs and the mandarin court officials, it was later decided that the voyages were not cost efficient and counter the conservative ideals of [[confucius|confucianism]].{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} After Zheng He's voyages, China reduced extravagent maritime voyages due to the [[Hai jin]] order, and initiated policy of isolationism. Although historians such as [[John Fairbank]] and [[Joseph Needham]] popularized this view in the 1950s, [[Han Chinese]] historians in modern times point out that Chinese maritime commerce did not totally stop after Zheng He, that Chinese ships continued to dominate [[Southeast Asia]]n commerce until the 19th century and that active Chinese trading with [[India]] and [[East Africa]] continued long after the time of Zheng. The travels of the Chinese ''[[Junk Keying]]'' to the [[United States]] and [[England]] between 1846 and 1848 testify to the power of Chinese shipping until the 19th century. Moreover [[revisionist historian]]s such as [[Jack Goldstone]] argue that the Zheng He voyages ended for practical reasons that did not reflect the technological level of China, as many naval technologies were continually being innovated and developed.<ref>{{cite web |

||

| last = Goldstone |

| last = Goldstone |

||

| first = Jack |

| first = Jack |

||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

| url = http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/10/114.html}}</ref> |

| url = http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/10/114.html}}</ref> |

||

Although the Ming |

Although the Ming emperor did ban shipping with the ''[[Hai jin]]'' edict, they eventually lifted this ban. The alternative view cites the fact that by banning oceangoing shipping, the Ming (and later Qing) dynasties forced countless numbers of people into [[black market]] [[smuggling]]. This reduced government tax revenue and increased [[piracy]]. The lack of an oceangoing navy then left China highly vulnerable to the [[Wokou]] pirates that ravaged China in the 16th century. |

||

Richard von Glahn ([[University of California, Los Angeles]] Professor of History and a specialist in Chinese history) commented that a majority of school history texts present Zheng He wrongly; they "''offer counterfactual arguments''", and "''emphasize China's missed opportunity.''" The "''narrative emphasizes the failure''" instead of Zheng He's accomplishments. He goes on to claim that "''Zheng He reshaped Asia.''" According to him, maritime history in the fifteenth century is essentially the Zheng He story and the effects of Zheng He's voyages. |

Richard von Glahn ([[University of California, Los Angeles]] Professor of History and a specialist in Chinese history) commented that a majority of school history texts present Zheng He wrongly; they "''offer counterfactual arguments''", and "''emphasize China's missed opportunity.''" The "''narrative emphasizes the failure''" instead of Zheng He's accomplishments. He goes on to claim that "''Zheng He reshaped Asia.''" According to him, maritime history in the fifteenth century is essentially the Zheng He story and the effects of Zheng He's voyages. |

||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

In 1449 Mongolian [[cavalry]] ambushed a land expedition personally led by the emperor [[Zhengtong]] less than a day's march from the walls of the capital. In the [[Battle of Tumu Fortress]] the Mongolians wiped out the Chinese army and captured the emperor. This battle had two salient effects. First, it demonstrated the clear threat posed by the northern nomads. Second, the Mongols caused a political crisis in China when they released Zhengtong after his half-brother had proclaimed himself the new [[Jingtai]] emperor. Not until 1457 did political stability return when Zhengtong recovered the throne. Upon his return to power China abandoned the strategy of annual land expeditions and instead embarked upon a massive and expensive expansion of the [[Great Wall of China]]. In this environment, funding for naval expeditions simply did not happen. |

In 1449 Mongolian [[cavalry]] ambushed a land expedition personally led by the emperor [[Zhengtong]] less than a day's march from the walls of the capital. In the [[Battle of Tumu Fortress]] the Mongolians wiped out the Chinese army and captured the emperor. This battle had two salient effects. First, it demonstrated the clear threat posed by the northern nomads. Second, the Mongols caused a political crisis in China when they released Zhengtong after his half-brother had proclaimed himself the new [[Jingtai]] emperor. Not until 1457 did political stability return when Zhengtong recovered the throne. Upon his return to power China abandoned the strategy of annual land expeditions and instead embarked upon a massive and expensive expansion of the [[Great Wall of China]]. In this environment, funding for naval expeditions simply did not happen. |

||

[[File:Zheng He's tomb, Nanjing.jpg|thumb|220px|Zheng He's tomb in [[Nanjing]].]] |

[[File:Zheng He's tomb, Nanjing.jpg|thumb|220px|Zheng He's tomb in [[Nanjing]].]] |

||

==Map== |

|||

[[Image:Zhenghemap.jpg|thumb|right|''Zheng He Map'', 1763; Collection of Liu Gang<ref name=wade>Geoff Wade [http://www.e-perimetron.org/Vol_2_4/Wade.pdf The “Liu/Menzies” World Map: A Critique] e-Perimetron, Vol. 2, No. 4, Autumn 2007 pp.273-280 ISSN 1790-3769</ref>]] |

|||

In January 2006, [[BBC News]] and ''[[The Economist]]'' both published news regarding the exhibition of a Chinese sailing map with detailed descriptions of both Native Americans and Native Australians. The map (''at right'') was dated 1763, and was believed to be a copy of an earlier map made in 1418. [[Gavin Menzies]] provided some evidence so show that the map demonstrates that Zheng He sailed to the Americas and Australia. |

|||

[[Image:ZhenghemapAmerica.jpg|thumb|upright|Detail, ''Zheng He Map,'' phonetic transcription of "North America"]] |

|||

According to the map's owner, Liu Gang, a Chinese lawyer and collector, he purchased the map in 2001 from a Shanghai dealer. A number of authorities on Chinese history have questioned the authenticity of the map while others have supported it. Some point to the use of the [[Mercator projection|Mercator-style projection]], its accurate reckoning of [[longitude]] and its North-based orientation. None of these features was used in the best maps made in either Asia or Europe during this period (for example see the [[Kangnido map]] (1410) and the [[Fra Mauro map]] (1459)). Also mentioned is the depiction of the erroneous [[Island of California]], a mistake commonly repeated in European maps from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. On the map the American continent is labelled phonetically "A-me-ri-ca" (今名北[[亞墨利加]], literally: "Now Name Northern A-me-ri-ca," ''see detail''). This translation was unknown in Ming Dynasty, and is known to be a borrowing from the West, ([[Amerigo Vespucci]]). |

|||

==Relics== |

==Relics== |

||

Revision as of 18:11, 31 May 2010

Zheng He (simplified Chinese: 郑和; traditional Chinese: 鄭和; pinyin: Zhèng Hé; Wade–Giles: Cheng Ho; Birth name: 馬和 Ma He. Also known as: 馬三寶 / 马三宝; pinyin: Mǎ Sānbǎo, Arabic/Persian name: حاجی محمود شمس Hajji Mahmud Shams) (1371–1435), was a Hui Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat and fleet admiral, who commanded voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, and East Africa, collectively referred to as the travels of "Eunuch Sanbao to the Western Ocean" (Chinese: 三保太監下西洋) or "Zheng He to the Western Ocean", from 1405 to 1433.

Life

Zheng He was originally named 'Ma He' and was born in 1371.[1] He was the second son of a Muslim family which also had four daughters, from Kunyang, present day Jinning, just south of Kunming near the southwest corner of Lake Tian in Yunnan.[2][3][4]

He was the great great great grandson of Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, a Persian who served in the administration of the Mongolian Empire and was appointed governor of Yunnan during the early Yuan Dynasty.[5][6] Both his grandfather and great-grandfather carried the title of Hajji, which indicates they had made the pilgrimage to Mecca. His great-grandfather was named Bayan and may have been a member of a Mongol garrison in Yunnan.[2]

In 1381, the year his father was killed, following the defeat of the Northern Yuan, a Ming army was dispatched to Yunnan to put down the Mongol rebel Basalawarmi. Ma He, then only eleven years old, was captured and made a eunuch. He was sent to the Imperial court, where he was called 'San Bao' meaning 'Three Jewels.' He eventually became a trusted adviser of the Yongle Emperor (r. 1403-1424), assisting him in deposing his predecessor, the Jianwen Emperor. In return for meritorious service, the eunuch received the name Zheng He from the Yongle Emperor.[2][4][7]

In 1425 the Hongxi Emperor appointed him to be Defender of Nanjing. In 1428 the Xuande Emperor ordered him to complete the construction of the magnificent Buddhist nine-storied Da Baoen Temple in Nanjing, and in 1430 appointed him to lead the seventh and final expedition to the "Western Ocean".[8] Zheng He died during the treasure fleet's last voyage, on the returning trip after the fleet reached Hormuz in 1433.

Expeditions

Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming government sponsored a series of seven naval expeditions. Emperor Yongle designed them to establish a Chinese presence, impose imperial control over trade, and impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean basin. He also might have wanted to extend the tributary system.

Zheng He was placed as the admiral in control of the huge fleet and armed forces that undertook these expeditions. Wang Jinghong was appointed his second in command. Zheng He's first voyage consisted of a fleet of 317 treasure ships[9][10][11] (other sources say 200 ships) holding almost 28,000 crewmen (each ship housing up to 500 men).[9]

Zheng He's fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Malay Archipelago and Thailand (at the time called Siam), dispensing and receiving goods along the way.[11] Zheng He presented gifts of gold, silver, porcelain and silk; in return, China received such novelties as ostriches, zebras, camels, ivory and giraffes.[11][12][13]

Zheng He generally sought to attain his goals through diplomacy, and his large army awed most would-be enemies into submission.[citation needed] But a contemporary reported that Zheng He "walked like a tiger" and did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary to impress foreign peoples with China's military might.[citation needed] He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and southeast Asian waters. He also waged a land war against the Kingdom of Kotte in Ceylon, and he made displays of military force when local officials threatened his fleet in Arabia and East Africa. From his fourth voyage, he brought envoys from thirty states who traveled to China and paid their respects at the Ming court.

In 1424, the Yongle Emperor died. His successor, the Hongxi Emperor (reigned 1424–1425), decided to stop the voyages during his short reign. Zheng He made one more voyage under the Xuande Emperor (reigned 1426–1435), but after that the voyages of the Chinese treasure ship fleets were ended. Zheng He died during the treasure fleet's last voyage. Although he has a tomb in China, it is empty: he was, like many great admirals, buried at sea.[14]

Voyages

| Order | Time | Regions along the way[15] |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Voyage | 1405–1407 | Champa, Java, Palembang, Malacca, Aru, Sumatra, Lambri, Ceylon, Kollam, Cochin, Calicut |

| 2nd Voyage | 1407–1409 | Champa, Java, Siam, Cochin, Ceylon |

| 3rd Voyage | 1409–1411 | Champa, Java, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Quilon, Cochin, Calicut, Siam, Lambri, Kaya, Coimbatore, Puttanpur |

| 4th Voyage | 1413–1415 | Champa, Java, Palembang, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Cochin, Calicut, Kayal, Pahang, Kelantan, Aru, Lambri, Hormuz, Maldives, Mogadishu, Barawa, Malindi, Aden, Muscat, Dhufar |

| 5th Voyage | 1416–1419 | Champa, Pahang, Java, Malacca, Sumatra, Lambri, Ceylon, Sharwayn, Cochin, Calicut, Hormuz, Maldives, Mogadishu, Barawa, Malindi, Aden |

| 6th Voyage | 1421–1422 | Hormuz, East Africa, countries of the Arabian Peninsula |

| 7th Voyage | 1430–1433 | Champa, Java, Palembang, Malacca, Sumatra, Ceylon, Calicut, Hormuz... (17 states in total) |

Zheng He led seven expeditions to what the Chinese called "the Western Ocean" (Indian Ocean). He brought back to China many trophies and envoys from more than thirty kingdoms — including King Alagakkonara of Ceylon, who came to China as a captive to apologize to the Emperor.

The records of Zheng's last two voyages, which are believed to be his farthest, were unfortunately destroyed by the Ming emperor. Therefore it is never certain where Zheng has sailed in these two expeditions. The traditional view is that he went as far as Iran.

There are speculations that some of Zheng's ships may have traveled beyond the Cape of Good Hope. In particular, the Venetian monk and cartographer Fra Mauro describes in his 1459 Fra Mauro map the travels of a huge "junk from India" 2,000 miles into the Atlantic Ocean in 1420. What Fra Mauro meant by 'India' is not known and some scholars believe he meant an Arab ship.[16] "Heresy". 1421exposed.com. Retrieved 2008-09-01.</ref>

Zheng himself wrote of his travels:

We have traversed more than 100,000 li (50,000 kilometers or 30,000 miles) of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare… — Tablet erected by Zheng He, Changle, Fujian, 1432. Louise Levathes

Sailing charts

Zheng He's sailing charts were published in a book entitled Wubei Zhi (Treatise on Armament Technology) written in 1621 and published in 1628 but traced back to Zheng He's and earlier voyages.[17] It was originally a strip map 20.5 cm by 560 cm that could be rolled up, but was divided into 40 pages which vary in scale from 7 miles/inch in the Nanjing area to 215 miles/inch in parts of the African coast.[18]

There is little attempt to provide an accurate 2-D representation; instead the sailing instructions are given using a 24 point compass system with a Chinese symbol for each point, together with a sailing time/distance, which takes account of the local currents and winds. Sometimes depth soundings are also provided. It also shows bays, estuaries, capes and islands, ports and mountains along the coast, important landmarks (pagodas, temples) and shoal rocks. Of 300 named places outside China, more than 80% can be confidently located. There are also fifty observations of stellar altitude.

Size of the ships

Traditional and popular accounts of Zheng He's voyages have described a great fleet of gigantic ships, far larger than any other wooden ships in history. Most modern scholars consider these descriptions relatively accurate due to the fact that recent archaeological finds have revealed gigantic ship rudders in the old Ming dynasty shipbuilding facility in Nanjing.

Chinese records [citation needed] assert that Zheng He's fleet sailed as far as East Africa. According to medieval Chinese sources [citation needed], Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships.[19][20] The fleet included:

- Treasure ships (Chinese:宝船), used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (nine-masted, about 126.73 metres (416 ft) long and 51.84 metres (170 ft) wide), according to later writers [citation needed]. This is more or less the size and shape of a football field. The treasure ships purportedly could carry as much as 1,500 tons. 1[21][22] By way of comparison, a modern ship of about 1,200 tons is 60 meters (200 ft) long,[23] and the ships Christopher Columbus sailed to the New World in 1492 were about 70-100 tons and 17 meters (55 ft) long.[24]

- Equine ships (Chinese:馬船), carrying horses and tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (eight-masted, about 103 m (339 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide).[21]

- Supply ships (Chinese:粮船), containing staple for the crew (seven-masted, about 78 m (257 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide).[21]

- Troop transports (Chinese:兵船), six-masted, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (83 ft) wide.[21]

- Fuchuan warships (Chinese:福船), five-masted, about 50 m (165 ft) long.[21]

- Patrol boats (Chinese:坐船), eight-oared, about 37 m (120 ft) long.[21]

- Water tankers (Chinese:水船), with 1 month's supply of fresh water.[21]

Six more expeditions took place, from 1407 to 1433, with fleets of comparable size.[25]

If the accounts can be taken as factual, Zheng He's treasure ships were mammoth ships with nine masts, four decks, and were capable of accommodating more than 500 passengers, as well as a massive amount of cargo. Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta both described multi-masted ships carrying 500 to 1000 passengers in their translated accounts.[26] Niccolò Da Conti, a contemporary of Zheng He, was also an eyewitness of ships in Southeast Asia, claiming to have seen 5 masted junks weighing about 2000 tons[27] There are even some sources that claim some of the treasure ships might have been as long as 600 feet.[28][29] On the ships were navigators, explorers, sailors, doctors, workers, and soldiers along with the translator and diarist Gong Zhen (simplified Chinese: 巩珍; traditional Chinese: 鞏珍; pinyin: gŏng zhēn).

Modern study of ship dimensions

According to recent research by professor of marine engineering Xin Yuanou, the length of many of the ships has been estimated at 59 m,[30] but is under heavy dispute by other scholars.[31]

The largest ships in the fleet, the treasure ships described in Chinese chronicles, would have been several times larger than any wooden ship ever recorded in history, surpassing l'Orient (65 m long) which was built in the late 18th century. The first ships to attain 126 m long were 19th century steamers with iron hulls. Some scholars argue that it is highly unlikely that Zheng He's ship was 450 feet in length, some estimating that they were 390–408 feet long and 160–166 feet wide instead[32] while others put them as 200–250 feet in length.[33]

One explanation for the seemingly inefficient size of these colossal ships was that the largest 44 Zhang treasure ships were merely used by the Emperor and imperial bureaucrats to travel along the Yangtze for court business, including reviewing Zheng He's expedition fleet. The Yangtze river, with its calmer waters, may have been navigable by these treasure ships. Zheng He, a court eunuch, would not have had the privilege in rank to command the largest of these ships, seaworthy or not. The main ships of Zheng He's fleet were instead 6 masted 2000-liao ships.[30][34]

A replica (4 feet long, 1 foot and 8 inches wide, and 3 feet tall) of Zheng He’s largest treasure boat will be on display at the lecture session. According to the maker of the replica, Quanzhou Maritime Museum and China Ancient Ship Modeling Center, the original treasure boat was 125 meters long and 51 meters wide, with a maximum loading capacity of 7,000 tons and total water displacement of 14,800 tons.[35]

Accounts of medieval travellers

The characteristics of the Chinese ships of the period are described by Western travelers to the East, such as Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo. According to Ibn Battuta, who visited China in 1347:

…We stopped in the port of Calicut, in which there were at the time thirteen Chinese vessels, and disembarked. China Sea traveling is done in Chinese ships only, so we shall describe their arrangements. The Chinese vessels are of three kinds; large ships called chunks (junks), middle sized ones called zaws (dhows) and the small ones kakams. The large ships have anything from twelve down to three sails, which are made of bamboo rods plaited into mats. They are never lowered, but turned according to the direction of the wind; at anchor they are left floating in the wind.

Three smaller ones, the "half", the "third" and the "quarter", accompany each large vessel. These vessels are built in the towns of Zaytun and Sin-Kalan. The vessel has four decks and contains rooms, cabins, and saloons for merchants; a cabin has chambers and a lavatory, and can be locked by its occupants.

This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three ells in length. When these walls have thus been built the lower deck is fitted in and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished." (Ibn Battuta).[citation needed]

Zheng He and Islam in Southeast Asia

| Part of a series on Islam in China |

|---|

|

|

|

Accounts contemporary to Zheng He's era suggest he adhered to the islamic faith; these include the writings of Ma Huan, Zheng He's chronicler, interpreter, and fellow Muslim, who travelled with him on many of his voyages.[36] As evidence of Zheng He's high regard for temples and places of worship of other religions, the Galle Trilingual Inscription stone tablet, erected by Zheng He around 1410 in Sri Lanka records details about contributions of gold, silver, and silk that he made at a Buddhist mountain temple.[37][38] Also, a commemorative pillar at the temple of the Taoist goddess Tian Fei, the Celestial Spouse, in Fujian province records details about his voyages, as well as his veneration and respect for the Goddess.[39] It has the inscription:

- We have traversed more than 100,000 li (50,000 kilometers) of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare…

- —Erected by Zheng He, Changle, Fujian, 1432. Louise Levathes

Indonesian religious leader and Islamic scholar Hamka (1908–1981) wrote in 1961: "The development of Islam in Indonesia and Malaya is intimately related to a Chinese Muslim, Admiral Zheng He."[40] In Malacca he built granaries, warehouses and a stockade, and most probably he left behind many of his Muslim crews. Much of the information on Zheng He's voyages was compiled by Ma Huan, also Muslim, who accompanied Zheng He on several of his inspection tours and served as his chronicler / interpreter. In his book 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores' (Chinese: 瀛涯勝覽) written in 1416, Ma Huan gave very detailed accounts of his observations of the peoples' customs and lives in ports they visited. Zheng He had many Muslim Eunuchs as his companions. At the time when his fleet first arrived in Malacca, there were already Chinese of the 'Muslim' faith living there. Ma Huan talks about them as tángrén (Chinese: 唐人) who were Muslim. At their ports of call, they actively propagated the Islamic faith, established Chinese Muslim communities, and built mosques.

Indonesian scholar Slamet Muljana writes: "Zheng He built Chinese Muslim communities first in Palembang, then in San Fa (West Kalimantan), subsequently he founded similar communities along the shores of Java, the Malay Peninsula and the Philippines. They propagated the Islamic faith according to the Hanafi school of thought and in Chinese language."

Li Tong Cai, in his book 'Indonesia – Legends and Facts', writes: "in 1430, Zheng He had already successfully established the foundations of the Hui religion Islam. After his death in 1434, Hajji Yan Ying Yu became the force behind the Chinese Muslim community, and he delegated a few local Chinese as leaders, such as trader Sun Long from Semarang, Peng Rui He and Hajji Peng De Qin. Sun Long and Peng Rui He actively urged the Chinese community to 'Javanise'. They encouraged the younger Chinese generation to assimilate with the Javanese society, to take on Javanese names and their way of life. Sun Long's adopted son Chen Wen, also named Radin Pada is the son of King Majapahit and his Chinese wife." It seems likely that Chen Wen is the same Raden Patah who had a Chinese mother and was a student and/or cousin of Sunan Ampel.[41]

After Zheng He's death, Chinese naval expeditions were suspended. The Hanafi Islam that Zheng He and his people propagated lost almost all contact with Islam in China, and gradually was totally absorbed by the local Shafi’i school of thought. When Melaka was successively colonised by the Portuguese, the Dutch, and later the British, Chinese were discouraged from converting to Islam. Many of the Chinese Muslim mosques became San Bao Chinese temples commemorating Zheng He. After a lapse of 600 years, the influence of Chinese Muslims in Malacca declined to almost nil.[42] In many ways, Zheng He can be considered a major founder of the present community of Chinese Indonesians.

In Malacca

According to the Malaysian history, Sultan Mansur Shah (ruled 1459–1477) dispatched Tun Perpatih Putih as his envoy to China and carried a letter from the Sultan to the Ming Emperor. Tun Perpatih succeeded in impressing the Emperor of Ming with the fame and grandeur of Sultan Mansur Shah. In the year 1459, a princess Hang Li Po (or Hang Liu), was sent by the emperor of Ming to marry Malacca Sultan Mansur Shah (ruled 1459–1477).[43] The princess came with her entourage 500 sons of ministers and a few hundred handmaidens.[citation needed] They eventually settled in Bukit Cina, Malacca. Considering the population of Malacca at that time, it is likely that a significant fraction of the bumiputra intermarried with them. The descendants of these mixed marriages are locally known today as peranakan and still use the honorifics Baba (male title) and Nyonya (female title).

In Malaysia today, many people believe it was Admiral Zheng He (died 1433) who sent princess Hang Li Po to Malacca in year 1459. However there is no record of Hang Li Po (or Hang Liu) in Ming documents, she is known only from Malacca folklore.

Connection to the history of Late Imperial China

Under the Emperor's patronage and direct imperial decree, Zheng He's initial objective was [citation needed]to enroll all the countries of the world into the Ming tributary system, but after the death of the emperor, due to a power struggle between the eunuchs and the mandarin court officials, it was later decided that the voyages were not cost efficient and counter the conservative ideals of confucianism.[citation needed] After Zheng He's voyages, China reduced extravagent maritime voyages due to the Hai jin order, and initiated policy of isolationism. Although historians such as John Fairbank and Joseph Needham popularized this view in the 1950s, Han Chinese historians in modern times point out that Chinese maritime commerce did not totally stop after Zheng He, that Chinese ships continued to dominate Southeast Asian commerce until the 19th century and that active Chinese trading with India and East Africa continued long after the time of Zheng. The travels of the Chinese Junk Keying to the United States and England between 1846 and 1848 testify to the power of Chinese shipping until the 19th century. Moreover revisionist historians such as Jack Goldstone argue that the Zheng He voyages ended for practical reasons that did not reflect the technological level of China, as many naval technologies were continually being innovated and developed.[45]

Although the Ming emperor did ban shipping with the Hai jin edict, they eventually lifted this ban. The alternative view cites the fact that by banning oceangoing shipping, the Ming (and later Qing) dynasties forced countless numbers of people into black market smuggling. This reduced government tax revenue and increased piracy. The lack of an oceangoing navy then left China highly vulnerable to the Wokou pirates that ravaged China in the 16th century.

Richard von Glahn (University of California, Los Angeles Professor of History and a specialist in Chinese history) commented that a majority of school history texts present Zheng He wrongly; they "offer counterfactual arguments", and "emphasize China's missed opportunity." The "narrative emphasizes the failure" instead of Zheng He's accomplishments. He goes on to claim that "Zheng He reshaped Asia." According to him, maritime history in the fifteenth century is essentially the Zheng He story and the effects of Zheng He's voyages.

Von Glahn claims that Zheng He's influence lasted beyond his age, may be seen as the tip of an iceberg, and there is much more to the story of maritime trade and other relationships in Asia in the fifteenth century and beyond.[46]

State-sponsored Ming naval efforts declined dramatically after Zheng's voyages. Starting in the early 15th century, China experienced increasing pressure from resurgent Mongolian tribes from the north. In recognition of this threat and possibly to move closer to his family's historical geographic power base, in 1421 the emperor Yongle moved the capital north from Nanjing to present-day Beijing. From the new capital he could apply greater imperial supervision to the effort to defend the northern borders. At considerable expense, China launched annual military expeditions from Beijing to weaken the Mongolians. The expenditures necessary for these land campaigns directly competed with the funds necessary to continue naval expeditions.

In 1449 Mongolian cavalry ambushed a land expedition personally led by the emperor Zhengtong less than a day's march from the walls of the capital. In the Battle of Tumu Fortress the Mongolians wiped out the Chinese army and captured the emperor. This battle had two salient effects. First, it demonstrated the clear threat posed by the northern nomads. Second, the Mongols caused a political crisis in China when they released Zhengtong after his half-brother had proclaimed himself the new Jingtai emperor. Not until 1457 did political stability return when Zhengtong recovered the throne. Upon his return to power China abandoned the strategy of annual land expeditions and instead embarked upon a massive and expensive expansion of the Great Wall of China. In this environment, funding for naval expeditions simply did not happen.

Map

In January 2006, BBC News and The Economist both published news regarding the exhibition of a Chinese sailing map with detailed descriptions of both Native Americans and Native Australians. The map (at right) was dated 1763, and was believed to be a copy of an earlier map made in 1418. Gavin Menzies provided some evidence so show that the map demonstrates that Zheng He sailed to the Americas and Australia.

According to the map's owner, Liu Gang, a Chinese lawyer and collector, he purchased the map in 2001 from a Shanghai dealer. A number of authorities on Chinese history have questioned the authenticity of the map while others have supported it. Some point to the use of the Mercator-style projection, its accurate reckoning of longitude and its North-based orientation. None of these features was used in the best maps made in either Asia or Europe during this period (for example see the Kangnido map (1410) and the Fra Mauro map (1459)). Also mentioned is the depiction of the erroneous Island of California, a mistake commonly repeated in European maps from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. On the map the American continent is labelled phonetically "A-me-ri-ca" (今名北亞墨利加, literally: "Now Name Northern A-me-ri-ca," see detail). This translation was unknown in Ming Dynasty, and is known to be a borrowing from the West, (Amerigo Vespucci).

Relics

- Nanjing Tianfeigong (南京天妃宫)

Zheng He built Tianfeigong (天妃宫, Tianfei palace) in Nanjing after the return of their first western voyage in 1407.

- Stele of Tongfan Deed (通番事跡碑)

The stele of Tongfan Deed (通番事跡, deed of foreign connection and exchange) is located in the Tianfeigong in Taicang where they start their journey. It was submerged and disappeared and has been rebuilt.

- Stele of Record of Tianfei Showing Her Presence and Power (天妃靈應之記碑)

In order to impetrate and thank the bless of Tianfei, Zheng He and his colleagues rebuilt Tianfeigong at Nanshan, Changle County, Fujian province before their 7th western voyage. They founded a stele with the inscription title Tian Fei Ling Ying Zhi Ji (天妃靈應之記, Record of Tianfei Showing Her Presence and Power) there, which tells about their voyages.

- Zheng He Stele in Sri Lanka

Galle Trilingual Inscription in Sri Lanka was discovered in the city of Galle in 1911 and is preserved in the Sri Lanka National Museum. Three languages were used for inscription: Chinese, Tamil and Persian.

Commemoration

Tomb and museum

Zheng He's tomb in Nanjing has been repaired and a small museum has been built next to it, although his body is missing as he was buried at sea off the Malabar coast near Calicut in Western India.[citation needed] However, his sword and other personal possessions were interred in the typical Muslim tomb inscribed with Arabic characters.

Maritime Day

In the People's Republic of China, 11 July is Maritime Day (中国航海日) and is devoted to the memory of Zheng He's first voyage.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Ooi Keat Gin Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to Timo ABC-CLIO Ltd (30 April 2004) ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2 p.324

- ^ a b c Mills (1970), p. 5.

- ^ Levathes (1994), p. 61.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture, p. 621. (2000) Dorothy Perkins. Roundtable Press, New York. ISBN 0-8160-2693-9 (hc); ISBN 0-8160-4374-4 (pbk).

- ^ Shih-Shan Henry Tsai: Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press 2002, ISBN 9780295981246, p. 38 (restricted online copy, p. 38, at Google Books)

- ^ Chunjiang Fu, Choo Yen Foo, Yaw Hoong Siew: The great explorer Cheng Ho. Ambassador of peace. Asiapac Books Pte Ltd 2005, ISBN 9789812294104, p. 7-8 (restricted online copy, p. 8, at Google Books)

- ^ Levathes (1994), pp. 61-63.

- ^ Mills (1970), p. 6.

- ^ a b "The Archaeological Researches into Zheng He's Treasure Ships". Travel-silkroad.com. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ Richard Gunde. "Zheng He's Voyages of Discovery". UCLA Asia Institute. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ a b c Tamura, Eileen H. (1997). China: Understanding Its Past. University of Hawaii Press. p. 70. ISBN 0824819233.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cromer, Alan (1995). Uncommon Sense: The Heretical Nature of Science. Oxford University Press US. p. 117. ISBN 0195096363.

- ^ Shih-Shan Henry Tsai (2002). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. p. 206. ISBN 9780295981246.

- ^ "The Seventh and Final Grand Voyage of the Treasure Fleet". Mariner.org. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ Maritime Silk Road 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 7-5085-0932-3

- ^ "Slide #249 Monograph". Henry-davis.com. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ Mei-Ling Hsu (1988). Chinese Marine Cartography: Sea Charts of Pre-Modern China. Vol. 40, pp96-112 (Imago Mundi ed.).

- ^ Mills, J.V. (1970). Ma Huan Ying Yai Sheng Lan: The overall survey of the ocean shores. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dreyer (2006): 122–124

- ^ "Briton charts Zheng He's course across globe". Chinaculture.org. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g "History of the Ming dynasty" «明史», Zhang Tingyu chief editor, published 1737, “四十四丈一十八丈” Cite error: The named reference "ming" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Eunuch Sanbao's Journey to the Western Seas" «三宝太监西洋通俗演义记», Luo Maodeng, published 1597, “宝船长四十四丈四,阔一十八丈,每只船上有九道桅”

- ^ "Flower Class Corvette - A Ship of 925 tons standard displacement when built, which increased to 1,180 tons due to modifications". Fcca.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ "Columbus's Ships<!- Bot generated title ->". Columbusnavigation.com. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ Dreyer (2006)

- ^ Science and Civilization in China, Joseph Needham, Volume 4, Section 3, pp.460-470

- ^ Science and Civilization in China, Joseph Needham, Volume 4, Section 3, p.452

- ^ Taiwan: A New History, Murray A. Rubinstein, page 49, M. E. Sharp, 1999, ISBN 1-56324-815-8

- ^ Chinese discoverers dwarfed European travels, Tony Weaver, IOL, November 11, 2002.

- ^ a b Xin Yuanou: Guanyu Zheng He baochuan chidu de jishu fenxi (A Technical Analysis of the Size of Zheng He's Ships). Shanghai 2002, p.8

- ^ Sally K.Church: The Colossal Ships of Zheng He - Image or Reality? in: Claudine Salmon (eds.): Zheng He - Images & Perceptions. South China and Maritime Asia. Vol. 15. Roderich Ptak, Thomas Höllmann. O. Harrasowitz (eds.), Wiesbaden 15.2005, pp.155-176. ISBN 3-447-05114-0 ISSN 0945-9286

- ^ When China Ruled the Seas, Louise Levathes, p.80

- ^ "Zheng He : An investigation into the plausibility of 450-ft treasure ships ", Sally K. Church

- ^ The Archeological Researches into Zheng He's Treasure Ships, SilkRoad webpage.

- ^ "Guy Alitto to speak on famed Chinese Navigator.www". News.uchicago.edu. 2005-08-04. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ Ying-yai sheng-lan: The overall survey of the ocean's shores, by Ma Huan

- ^ A Peaceful Mariner and Diplomat - Xinhua News Agency July 12, 2005

- ^ Association for Asian Studies (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644: Volume I [1], A-L (Hardcover). New York City, New York: Columbia University Press . ISBN 0-231-03833-1

- ^ "Zheng He's Inscription". Hist.umn.edu. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ Chinese Muslims in Malaysia, History and Development by Rosey Wang Ma

- ^ Wali Songo: The Nine Walis

- ^ Suryadinata Leo (2005). Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia. Singapore Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 981-230-329-4.

{{cite book}}: External link in|nopp=|nopp=[1](help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Jin, Shaoqing (2005). Office of the People's Goverernment of Fujian Province (ed.). Zheng He's voyages down the western seas. Fujian, China: China Intercontinental Press. p. 58. ISBN 9787508507088. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ^ Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", Natural History Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 [2]

- ^ Goldstone, Jack. "The Rise of the West - or Not? A Revision to Socio-economic History".

- ^ "Zheng He's Voyages of Discovery|UCLA center for Chinese Study|". International.ucla.edu. 2004-04-20. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ Geoff Wade The “Liu/Menzies” World Map: A Critique e-Perimetron, Vol. 2, No. 4, Autumn 2007 pp.273-280 ISSN 1790-3769

References

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2006). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming, 1405–1433 (Library of World Biography Series). Longman. ISBN 0-321-08443-8.

- Levathes, Louise (1997). When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. Oxford University Press, trade paperback. ISBN 0-19-511207-5.

- Mills, J. V. G. (1970). Ying-yai Sheng-lan, The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores (1433), translated from the Chinese text edited by Feng Ch'eng Chun with introduction, notes and appendices by J. V. G. Mills. White Lotus Press. Reprinted 1970, 1997. ISBN 974-8496-78-3.

- Ming-Yang, Dr Su. 2004 Seven Epic Voyages of Zheng He in Ming China (1405–1433)

- Viviano, Frank (2005). "China's Great Armada." National Geographic, 208(1):28–53, July.

- Joseph Kahn: China Has an Ancient Mariner to Tell You About. In The New York Times of 2005-7-20.

- Newsletter, in Chinese, on academic research on the Zheng He voyages

- Cummins, Joseph (2006). History's Great Untold Stories. Murdoch Books. ISBN 1-74045-808-7.

- Shipping News: Zheng He's Sexcentenary - China Heritage Newsletter, June 2005, ISSN 1833-8461. Published by the China Heritage Project of The Australian National University.

External links

- Zheng He - The Chinese Muslim Admiral

- Zheng He Journey to Arabia

- Zheng He 600th Anniversary

- BBC radio programme "Swimming Dragons".

- TIME magazine special feature on Zheng He (August 2001)

- China's Great Armada and its Leader Zheng He

- Virtual exhibition from elibraryhub.com

- Ship imitates ancient vessel navigated by Zheng He at peopledaily.com (September 25, 2006)

- Articles needing cleanup from May 2010

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from May 2010

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from May 2010

- 1371 births

- 1433 deaths

- People from Yunnan

- Hui people

- Chinese Muslims

- Chinese explorers

- Explorers of Asia

- Explorers of Africa

- Chinese admirals

- Chinese geographers

- Ancient geographers

- Medieval Islamic travel writers

- Ming Dynasty eunuchs

- Naval history of China

- Chinese diplomats

- Burials at sea