Paul Krugman: Difference between revisions

Vision Thing (talk | contribs) rv FurrySings; no consenus for these edits |

Reverted to revision 477115343 by NuclearWarfare: whatever I say here VT will think I am biased so I'll just let him fill this in for me. (TW) |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

'''Paul Robin Krugman''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|k|r|uː|ɡ|m|ən}};<ref>See [http://inogolo.com/pronunciation/d1810/Paul_Krugman inogolo:pronunciation of Paul Krugman].</ref> born February 28, 1953) is an American [[economist]], Professor of Economics and International Affairs at the [[Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs]] at [[Princeton University]], Centenary Professor at the London School of Economics, and an [[op-ed]] [[columnist]] for ''[[The New York Times]]''.<ref>London School of Economics, Centre for Economic Performance, [http://cep.lse.ac.uk/_new/events/event.asp?id=92 Lionel Robbins Memorial Lectures 2009: The Return of Depression Economics]. Retrieved August 19, 2009.</ref><ref name="krugmanonline ">{{cite web|url=http://www.krugmanonline.com/about.php |title=About Paul Krugman |work=krugmanonline |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |accessdate=May 15, 2009}}</ref> In 2008, Krugman won the [[Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences]] for his contributions to [[New Trade Theory]] and [[economic geography|New Economic Geography]]. According to the Nobel Prize Committee, the prize was given for Krugman's work explaining the patterns of [[international trade]] and the geographic concentration of wealth, by examining the impact of [[Economy of scale|economies of scale]] and of consumer preferences for diverse goods and services.<ref name=NobelComments/> |

'''Paul Robin Krugman''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|k|r|uː|ɡ|m|ən}};<ref>See [http://inogolo.com/pronunciation/d1810/Paul_Krugman inogolo:pronunciation of Paul Krugman].</ref> born February 28, 1953) is an American [[economist]], Professor of Economics and International Affairs at the [[Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs]] at [[Princeton University]], Centenary Professor at the London School of Economics, and an [[op-ed]] [[columnist]] for ''[[The New York Times]]''.<ref>London School of Economics, Centre for Economic Performance, [http://cep.lse.ac.uk/_new/events/event.asp?id=92 Lionel Robbins Memorial Lectures 2009: The Return of Depression Economics]. Retrieved August 19, 2009.</ref><ref name="krugmanonline ">{{cite web|url=http://www.krugmanonline.com/about.php |title=About Paul Krugman |work=krugmanonline |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |accessdate=May 15, 2009}}</ref> In 2008, Krugman won the [[Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences]] for his contributions to [[New Trade Theory]] and [[economic geography|New Economic Geography]]. According to the Nobel Prize Committee, the prize was given for Krugman's work explaining the patterns of [[international trade]] and the geographic concentration of wealth, by examining the impact of [[Economy of scale|economies of scale]] and of consumer preferences for diverse goods and services.<ref name=NobelComments/> |

||

Krugman is known in academia for his work on [[international economics]] (including trade theory, economic geography, and international finance),<ref>Note: Krugman modeled a 'preference for diversity' by assuming a [[CES utility|CES utility function]] like that in A. Dixit and J. Stiglitz (1977), 'Monopolistic competition and optimal product diversity', ''American Economic Review'' 67.</ref><ref name=forbes131008>''Forbes'', October 13, 2008, [http://www.forbes.com/2008/10/13/krugman-nobel-economics-oped-cx_ap_1013panagariya.html "Paul Krugman, Nobel"]</ref> [[liquidity trap]]s and currency crises. He is the 14th most widely cited economist in the world today.<ref name=IDEAS/> |

Krugman is known in academia for his work on [[international economics]] (including trade theory, economic geography, and international finance),<ref>Note: Krugman modeled a 'preference for diversity' by assuming a [[CES utility|CES utility function]] like that in A. Dixit and J. Stiglitz (1977), 'Monopolistic competition and optimal product diversity', ''American Economic Review'' 67.</ref><ref name=forbes131008>''Forbes'', October 13, 2008, [http://www.forbes.com/2008/10/13/krugman-nobel-economics-oped-cx_ap_1013panagariya.html "Paul Krugman, Nobel"]</ref> [[liquidity trap]]s and currency crises. He is the 14th most widely cited economist in the world today.<ref name=IDEAS/> In a 2011 survey, US economics professors ranked Krugman as their favorite living economic thinker under the age of 60.<ref>Davis, William L, Bob Figgins, David Hedengren, and Daniel B. Klein. "Economic Professors' Favorite Economic Thinkers, Journals, and Blogs," ''[[Econ Journal Watch]]'' 8(2): 126-146, May 2011.[http://econjwatch.org/articles/economics-professors-favorite-economic-thinkers-journals-and-blogs-along-with-party-and-policy-views] </ref> |

||

{{as of|2008}}, Krugman has written 20 books and has published over 200 scholarly articles in professional journals and edited volumes.<ref>{{cite news|last=Rampell |first=Catherine |url=http://topics.nytimes.com/top/opinion/editorialsandoped/oped/columnists/paulkrugman/index.html |title=Paul Krugman Short Biography |publisher=New York Times |date= |accessdate=2011-10-04}}</ref> He has also written more than 750 columns dealing with current economic and political issues for ''[[The New York Times]]''. |

{{as of|2008}}, Krugman has written 20 books and has published over 200 scholarly articles in professional journals and edited volumes.<ref>{{cite news|last=Rampell |first=Catherine |url=http://topics.nytimes.com/top/opinion/editorialsandoped/oped/columnists/paulkrugman/index.html |title=Paul Krugman Short Biography |publisher=New York Times |date= |accessdate=2011-10-04}}</ref> He has also written more than 750 columns dealing with current economic and political issues for ''[[The New York Times]]''. |

||

| Line 140: | Line 140: | ||

== Commentator == |

== Commentator == |

||

In the summer preceding his Nobel Prize, Krugman was voted one of the world's top [[public intellectual]]s by half a million participants in [[Top 100 Public Intellectuals Poll|an online poll]] conducted by ''[[Foreign Policy (magazine)|Foreign Policy]]''.<ref>[http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2008/06/26/the_top_100_public_intellectualsmdashthe_final_rankings ''Foreign Policy'' (online), 26 June 2008]</ref> Since then, economist [[J. Peter Neary]] has noted that Krugman "has written on a wide range of topics, always combining one of the best prose styles in the profession with an ability to construct elegant, insightful and useful models."<ref name=neary>[[J. Peter Neary]] (2009), "Putting the 'New' into New Trade Theory: Paul Krugman's Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics", ''Scandinavian Journal of Economics'', 111(2), pp217-250</ref> Neary added that "no discussion of his work could fail to mention his transition from Academic Superstar to Public Intellectual. Through his extensive writings, including a regular column for ''[[The New York Times]]'', monographs and textbooks at every level, and books on economics and current affairs for the general public ... he has probably done more than any other writer to explain economic principles to a wide audience."<ref name=neary/> Krugman has been described as the most controversial economist in his generation<ref name=Hirsch/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.channel4.com/news/articles/world/china+the+financial+nexus++krugman/109620 |title="China the financial nexus" - Krugman |publisher=Channel4.com |date= |accessdate=2011-10-04}}</ref> and according to [[Michael Tomasky]] since 1992 he has moved "from being a center-left scholar to being a liberal polemicist."<ref name="tomaskyconlibrev"/> |

|||

From the mid-1990s onwards, Krugman wrote for ''[[Fortune (magazine)|Fortune]]'' (1997–99)<ref name=PWB>''Princeton Weekly Bulletin'', October 20, 2008, [http://www.princeton.edu/pr/pwb/volume98/issue07/krugman/ "Biography of Paul Krugman"], 98(7)</ref> and ''[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]]'' (1996–99),<ref name=PWB/> and then for ''[[The Harvard Business Review]]'', ''[[Foreign Policy (magazine)|Foreign Policy]]'', ''[[The Economist]]'', ''[[Harper's Magazine|Harper's]]'', and ''[[Washington Monthly]]''. In this period Krugman critiqued various positions commonly taken on economic issues from across the political spectrum, from [[protectionism]] and opposition to the [[World Trade Organization]] on the left to [[supply side economics]] on the right.<ref name=monthly/> |

From the mid-1990s onwards, Krugman wrote for ''[[Fortune (magazine)|Fortune]]'' (1997–99)<ref name=PWB>''Princeton Weekly Bulletin'', October 20, 2008, [http://www.princeton.edu/pr/pwb/volume98/issue07/krugman/ "Biography of Paul Krugman"], 98(7)</ref> and ''[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]]'' (1996–99),<ref name=PWB/> and then for ''[[The Harvard Business Review]]'', ''[[Foreign Policy (magazine)|Foreign Policy]]'', ''[[The Economist]]'', ''[[Harper's Magazine|Harper's]]'', and ''[[Washington Monthly]]''. In this period Krugman critiqued various positions commonly taken on economic issues from across the political spectrum, from [[protectionism]] and opposition to the [[World Trade Organization]] on the left to [[supply side economics]] on the right.<ref name=monthly/> |

||

| Line 295: | Line 295: | ||

Economist and former [[United States Secretary of the Treasury]] [[Lawrence Summers|Larry Summers]] has stated Krugman has a tendency to favor more extreme policy recommendations because "it’s much more interesting than agreement when you’re involved in commenting on rather than making policy."<ref name=nymag/> |

Economist and former [[United States Secretary of the Treasury]] [[Lawrence Summers|Larry Summers]] has stated Krugman has a tendency to favor more extreme policy recommendations because "it’s much more interesting than agreement when you’re involved in commenting on rather than making policy."<ref name=nymag/> |

||

According to Harvard professor of economics [[Robert Barro]], Krugman "has never done any work in Keynesian macroeconomics" and makes arguments that are politically convenient for him.<ref>[http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2009/02/an-interview-with-robert-barro/370/ An interview with Robert Barro] - [[The Atlantic]]</ref> Nobel laureate [[Edward Prescott]] charged that Krugman "doesn't command respect in the profession", as "no respectable macroeconomist" believes that [[economic stimulus]] works.<ref>[http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/content/mar2009/db2009038_985205.htm Economists Rush to Disagree About Crisis Solutions] - [[Bloomberg Businessweek]]</ref> |

According to Harvard professor of economics [[Robert Barro]], Krugman "has never done any work in Keynesian macroeconomics" and makes arguments that are politically convenient for him.<ref>[http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2009/02/an-interview-with-robert-barro/370/ An interview with Robert Barro] - [[The Atlantic]]</ref> In an interview with ''Businessweek'', Nobel laureate [[Edward Prescott]] charged that Krugman "doesn't command respect in the profession", as "no respectable macroeconomist" believes that [[economic stimulus]] works; although the same article notes that economists who support such stimulus form "probably a majority".<ref>[http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/content/mar2009/db2009038_985205.htm Economists Rush to Disagree About Crisis Solutions] - [[Bloomberg Businessweek]]</ref> |

||

=== Enron === |

=== Enron === |

||

Revision as of 17:04, 16 February 2012

Paul Krugman | |

|---|---|

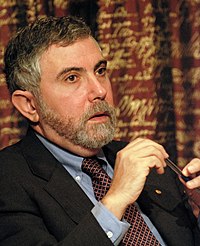

Krugman at a press conference at the Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm, 2008 | |

| Born | February 28, 1953 Albany, New York |

| Nationality | United States |

| Academic career | |

| Field | International economics, Macroeconomics |

| Institution | Princeton University, London School of Economics |

| School or tradition | New Keynesian economics |

| Alma mater | MIT (PhD) Yale University (BA) |

| Influences | John Maynard Keynes[1] John Hicks[1][2][3] Paul Samuelson[citation needed] |

| Contributions | International Trade Theory New Trade Theory New Economic Geography |

| Awards | John Bates Clark Medal (1991) Príncipe de Asturias Prize (2004) Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics (2008) |

| Information at IDEAS / RePEc | |

Paul Robin Krugman (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈkruːɡmən/;[6] born February 28, 1953) is an American economist, Professor of Economics and International Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University, Centenary Professor at the London School of Economics, and an op-ed columnist for The New York Times.[7][8] In 2008, Krugman won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography. According to the Nobel Prize Committee, the prize was given for Krugman's work explaining the patterns of international trade and the geographic concentration of wealth, by examining the impact of economies of scale and of consumer preferences for diverse goods and services.[9]

Krugman is known in academia for his work on international economics (including trade theory, economic geography, and international finance),[10][11] liquidity traps and currency crises. He is the 14th most widely cited economist in the world today.[12] In a 2011 survey, US economics professors ranked Krugman as their favorite living economic thinker under the age of 60.[13]

As of 2008[update], Krugman has written 20 books and has published over 200 scholarly articles in professional journals and edited volumes.[14] He has also written more than 750 columns dealing with current economic and political issues for The New York Times.

He also writes on various topics ranging from income distribution to international economics. Krugman considers himself a liberal, calling one of his books and his New York Times blog "The Conscience of a Liberal".[15] His commentary has attracted considerable comment and criticism.[16][17][18][19][20]

Personal life

Krugman is the son of David and Anita Krugman and the grandson of Jewish immigrants from Brest-Litovsk.[21] He was born in Albany, NY, and grew up in Nassau County, New York.[22] He graduated from John F. Kennedy High School in Bellmore.[23] He is married to Robin Wells, his second wife, a yoga instructor and academic economist who has collaborated on textbooks with Krugman.[24][25][26] Krugman reports that he is a distant relative of conservative journalist David Frum.[27] He has described himself as a "Loner. Ordinarily shy. Shy with individuals."[28] He currently lives with his wife in Princeton, New Jersey.

According to Krugman, his interest in economics began with Isaac Asimov's Foundation novels, in which the social scientists of the future use "psychohistory" to attempt to save civilization. Since "psychohistory" in Asimov's sense of the word does not exist, Krugman turned to economics, which he considered the next best thing.[29][30]

Academic career

Krugman earned his B.A. in economics from Yale University summa cum laude in 1974 and his PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1977. While at MIT he was part of a small group of MIT students sent to work for the Central Bank of Portugal for three months in summer 1976, in the chaotic aftermath of the Carnation Revolution.[31] From 1982 to 1983, he spent a year working at the Reagan White House as a staff member of the Council of Economic Advisers. He taught at Yale University, MIT, UC Berkeley, the London School of Economics, and Stanford University before joining Princeton University in 2000 as professor of economics and international affairs. He is also currently a centenary professor at the London School of Economics, and a member of the Group of Thirty international economic body. He has been a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research since 1979.[32] Most recently, Krugman was President of the Eastern Economic Association.

Paul Krugman has written extensively on international economics, including international trade, economic geography, and international finance. The Research Papers in Economics project ranked him as the 14th most influential economist in the world as of March 2011 based on his academic contributions.[12] Krugman's International Economics: Theory and Policy, co-authored with Maurice Obstfeld, is a standard undergraduate textbook on international economics.[33] He is also co-author, with Robin Wells, of an undergraduate economics text which he says was strongly inspired by the first edition of Paul Samuelson's classic textbook.[34] Krugman also writes on economic topics for the general public, sometimes on international economic topics but also on income distribution and public policy.

The Nobel Prize Committee stated that Krugman's main contribution is his analysis of the impact of economies of scale, combined with the assumption that consumers appreciate diversity, on international trade and on the location of economic activity.[9] The importance of spatial issues in economics has been enhanced by Krugman's ability to popularize this complicated theory with the help of easy-to-read books and state-of-the-art syntheses. "Krugman was beyond doubt the key player in 'placing geographical analysis squarely in the economic mainstream' ... and in conferring it the central role it now assumes."[35]

In 1978, Krugman wrote The Theory of Interstellar Trade, a tongue-in-cheek essay on computing interest rates on goods in transit near the speed of light. He says he wrote it to cheer himself up when he was "an oppressed assistant professor".[36]

New trade theory

Prior to Krugman's work, trade theory (see David Ricardo and Hecksher-Ohlin model) emphasized trade based on the comparative advantage of countries with very different characteristics, such as a country with a high agricultural productivity trading agricultural products for industrial products from a country with a high industrial productivity. However, in the 20th century, an ever larger share of trade occurred between countries with very similar characteristics, which is difficult to explain by comparative advantage. Krugman's explanation of trade between similar countries was proposed in a 1979 paper in the Journal of International Economics, and involves two key assumptions: that consumers prefer a diverse choice of brands, and that production favors economies of scale.[37] Consumers' preference for diversity explains the survival of different versions of cars like Volvo and BMW.[38] But because of economies of scale, it is not profitable to spread the production of Volvos all over the world; instead, it is concentrated in a few factories and therefore in a few countries (or maybe just one). This logic explains how each country may specialize in producing a few brands of any given type of product, instead of specializing in different types of products.

Many models of international trade now follow Krugman's lead, incorporating economies of scale in production and a preference for diversity in consumption.[9] This way of modeling trade has come to be called New Trade Theory.[35]

Krugman's theory also took into account transportation costs, a key feature in producing the "home market effect", which would later feature in his work on the new economic geography. The home market effect "states that, ceteris paribus, the country with the larger demand for a good shall, at equilibrium, produce a more than proportionate share of that good and be a net exporter of it."[35] The home market effect was an unexpected result, and Krugman initially questioned it, but ultimately concluded that the mathematics of the model were correct.[35]

When there are economies of scale in production, it is possible that countries may become 'locked in' to disadvantageous patterns of trade.[39] Nonetheless, trade remains beneficial in general, even between similar countries, because it permits firms to save on costs by producing at a larger, more efficient scale, and because it increases the range of brands available and sharpens the competition between firms.[40] Krugman has usually been supportive of free trade and globalization.[41][42] He has also been critical of industrial policy, which New Trade Theory suggests might offer nations rent-seeking advantages if "strategic industries" can be identified, saying it's not clear that such identification can be done accurately enough to matter.[43]

New economic geography

It took an interval of eleven years, but ultimately Krugman's work on New Trade Theory (NTT) converged to what is usually called the "new economic geography" (NEG), which Krugman began to develop in a seminal 1991 paper in the Journal of Political Economy.[44] In Krugman's own words, the passage from NTT to NEG was "obvious in retrospect; but it certainly took me a while to see it. ... The only good news was that nobody else picked up that $100 bill lying on the sidewalk in the interim."[45] This would become Krugman's most-cited academic paper: by early 2009, it had 857 citations, more than double his second-ranked paper.[35] Krugman called the paper "the love of my life in academic work."[46]

The "home market effect" that Krugman discovered in NTT also features in NEG, which interprets agglomeration "as the outcome of the interaction of increasing returns, trade costs and factor price differences."[35] If trade is largely shaped by economies of scale, as Krugman's trade theory argues, then those economic regions with most production will be more profitable and will therefore attract even more production. That is, NTT implies that instead of spreading out evenly around the world, production will tend to concentrate in a few countries, regions, or cities, which will become densely populated but will also have higher levels of income.[9][11]

International finance

Krugman has also been influential in the field of international finance. As a graduate student, Krugman visited the Federal Reserve Board, where Stephen Salant and Dale Henderson were completing their discussion paper on speculative attacks in the gold market. Krugman adapted their model for the foreign exchange market, resulting in a 1979 paper on currency crises in the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, which showed that fixed exchange rate regimes are unlikely to end smoothly: instead, they end in a sudden speculative attack.[47] Krugman's paper is considered one of the main contributions to the 'first generation' of currency crisis models,[48][49] and it is his second-most-cited paper (457 citations as of early 2009).[35]

In response to the global financial crisis of 2008, Krugman proposed, in an informal "mimeo" style of publication,[50] an "international finance multiplier", to help explain the unexpected speed with which the global crisis had occurred. He argued that when, "highly leveraged financial institutions [HLIs], which do a lot of cross-border investment [....] lose heavily in one market [...] they find themselves undercapitalized, and have to sell off assets across the board. This drives down prices, putting pressure on the balance sheets of other HLIs, and so on." Such a rapid contagion had hitherto been considered unlikely because of "decoupling" in a globalized economy.[51][52][53] He first announced that he was working on such a model on his blog, on October 5, 2008.[54] Within days of its appearance, it was being discussed on some popular economics-oriented blogs.[55][56] The note was soon being cited in papers (draft and published) by other economists,[57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64] even though it had not itself been through ordinary peer review processes.

Macroeconomics and fiscal policy

Krugman has done much to revive discussion of the liquidity trap as a topic in economics.[65][66][67][68] He recommended aggressive fiscal policy to counter Japan's lost decade in the 1990s, arguing that the country was mired in a Keynesian liquidity trap.[69][70][71] The debate he started at that time over liquidity traps and what policies best address them continues in the economics literature.[72]

Krugman had argued in The Return of Depression Economics that Japan was in a liquidity trap in the late 1990s, since the central bank could not drop interest rates any lower to escape economic stagnation.[73] The core of Krugman's policy proposal for addressing Japan's liquidity trap was inflation targeting, which, he argued "most nearly approaches the usual goal of modern stabilization policy, which is to provide adequate demand in a clean, unobtrusive way that does not distort the allocation of resources."[71] The proposal appeared first in a web posting on his academic site.[74] This mimeo-draft was soon cited, but was also misread by some as repeating his earlier advice that Japan's best hope was in "turning on the printing presses", as recommended by Milton Friedman, John Makin, and others.[75][76][77]

Krugman has since drawn parallels between Japan's 'lost decade' and the late 2000s recession, arguing that expansionary fiscal policy is necessary as the major industrialized economies are mired in a liquidity trap.[78] In response to economists who point out that the Japanese economy recovered despite not pursuing his policy prescriptions, Krugman maintains that it was an export-led boom that pulled Japan out of its economic slump in the late-90s, rather than reforms of the financial system.[79]

Nobel Memorial Prize

Krugman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, the sole recipient for 2008. This prize includes an award of about $1.4 million and was given to Krugman for his work associated with New Trade Theory and the New Economic Geography.[80] In the words of the prize committee, "By having integrated economies of scale into explicit general equilibrium models, Paul Krugman has deepened our understanding of the determinants of trade and the location of economic activity."[81]

Awards

- 1991, American Economic Association, John Bates Clark Medal.[82] Since it was awarded to only one person, once every two years (prior to 2009), The Economist has described the Clark Medal as 'slightly harder to get than a Nobel prize'.[83]

- 1992, Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AAAS).[32]

- 1995, Adam Smith Award of the National Association for Business Economics[84]

- 1998, Doctor honoris causa in Economics awarded by Free University of Berlin Freie Universität Berlin in Germany

- 2000, H.C. Recktenwald Prize in Economics, awarded by University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany.

- 2002, Editor and Publisher, Columnist of the Year.[85]

- 2004, Fundación Príncipe de Asturias (Spain), Prince of Asturias Awards in Social Sciences.[86]

- 2004, Doctor of Humane Letters honoris causa, Haverford College[87]

- 2008, Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics (formally The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel) for Krugman's contributions to New Trade Theory.[88] He became the twelfth John Bates Clark Medal winner to be awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize.

Author

In the 1990s, besides academic books and textbooks, Krugman increasingly began writing books for a general audience on issues he considered important for public policy. In The Age of Diminished Expectations (1990), he wrote in particular about the increasing US income inequality in the "New Economy" of the 1990s. He attributes the rise in income inequality in part to changes in technology, but principally to a change in political atmosphere which he attributes to Movement Conservatives.

In September 2003, Krugman published a collection of his columns under the title, The Great Unraveling, about the Bush administration's economic and foreign policies and the US economy in the early 2000s. His columns argued that the large deficits during that time were generated by the Bush administration as a result of decreasing taxes on the rich, increasing public spending, and fighting the Iraq war. Krugman wrote that these policies were unsustainable in the long run and would eventually generate a major economic crisis. The book was a best-seller.[83][89][90]

In 2007, Krugman published The Conscience of a Liberal, whose title references Barry Goldwater's Conscience of a Conservative.[91] It details the history of wealth and income gaps in the United States in the 20th century. The book describes how the gap between rich and poor declined greatly in middle of the century, and then widened in the last two decades to levels higher even than in the 1920s. In Conscience, Krugman argues that government policies played a much greater role than commonly thought both in reducing inequality in the 1930s through 1970s and in increasing it in the 1980s through the present, and criticizes the Bush administration for implementing policies that Krugman believes widened the gap between the rich and poor.

Krugman also argued that Republicans owed their electoral successes to their ability to exploit the race issue to win political dominance of the South.[92][93] Krugman argues that Ronald Reagan had used the "Southern Strategy" to signal sympathy for racism without saying anything overtly racist,[94] citing as an example Reagan's coining of the term "welfare queen".[95]

In his book, Krugman proposed a "new New Deal", which included placing more emphasis on social and medical programs and less on national defense.[96] Liberal journalist and author Michael Tomasky argued that in The Conscience of a Liberal Krugman is committed "to accurate history even when some fudging might be in order for the sake of political expediency."[92] In a review for The New York Times, Pulitzer prize-winning historian David M. Kennedy stated, "Like the rants of Rush Limbaugh or the films of Michael Moore, Krugman's shrill polemic may hearten the faithful, but it will do little to persuade the unconvinced".[97]

In late 2008, Krugman published a substantial updating of an earlier work, entitled "The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008". In the book, he discusses the failure of the United States regulatory system to keep pace with a financial system increasingly out-of-control, and the causes of and possible ways to contain the greatest financial crisis since the 1930s.

Commentator

In the summer preceding his Nobel Prize, Krugman was voted one of the world's top public intellectuals by half a million participants in an online poll conducted by Foreign Policy.[98] Since then, economist J. Peter Neary has noted that Krugman "has written on a wide range of topics, always combining one of the best prose styles in the profession with an ability to construct elegant, insightful and useful models."[99] Neary added that "no discussion of his work could fail to mention his transition from Academic Superstar to Public Intellectual. Through his extensive writings, including a regular column for The New York Times, monographs and textbooks at every level, and books on economics and current affairs for the general public ... he has probably done more than any other writer to explain economic principles to a wide audience."[99] Krugman has been described as the most controversial economist in his generation[100][101] and according to Michael Tomasky since 1992 he has moved "from being a center-left scholar to being a liberal polemicist."[92]

From the mid-1990s onwards, Krugman wrote for Fortune (1997–99)[32] and Slate (1996–99),[32] and then for The Harvard Business Review, Foreign Policy, The Economist, Harper's, and Washington Monthly. In this period Krugman critiqued various positions commonly taken on economic issues from across the political spectrum, from protectionism and opposition to the World Trade Organization on the left to supply side economics on the right.[102]

During the 1992 presidential campaign Krugman praised Bill Clinton's economic plan in The New York Times, and Clinton's campaign used some of Krugman's work on income inequality. At the time, it was considered likely that Clinton would offer him a position in the new administration, but allegedly Krugman's volatility and outspokenness caused Clinton to look elsewhere.[100] Krugman later said that he was "temperamentally unsuited for that kind of role. You have to be very good at people skills, biting your tongue when people say silly things."[102][103] In a Fresh Dialogues interview, Krugman added, "you have to be reasonably organized...I can move into a pristine office and within three days it will look like a grenade went off."[104]

In 1999, near the height of the dot com boom, The New York Times approached Krugman to write a bi-weekly column on "the vagaries of business and economics in an age of prosperity."[102] His first columns in 2000 addressed business and economic issues, but as the 2000 US presidential campaign progressed, Krugman increasingly focused on George W. Bush's policy proposals. According to Krugman, this was partly due to "the silence of the media - those 'liberal media' conservatives complain about...."[102] Krugman accused Bush of repeatedly misrepresenting his proposals, and criticized the proposals themselves.[102] After Bush's election, and his perseverance with his proposed tax cut in the midst of the slump (which Krugman argued would do little to help the economy but substantially raise the fiscal deficit), Krugman's columns grew angrier and more focused on the administration. As Alan Blinder put it in 2002, "There's been a kind of missionary quality to his writing since then ... He's trying to stop something now, using the power of the pen."[102] Partly as a result, Krugman's twice-weekly column on the Op-Ed page of The New York Times has made him, according to Nicholas Confessore, "the most important political columnist in America... he is almost alone in analyzing the most important story in politics in recent years – the seamless melding of corporate, class, and political party interests at which the Bush administration excels."[102] In an interview in late 2009, Krugman said his missionary zeal had changed in the post-Bush era and he described the Obama administration as "good guys but not as forceful as I'd like...When I argue with them in my column this is a serious discussion. We really are in effect speaking across the transom here."[105] Krugman says he's more effective at driving change outside the administration than inside it, "now, I'm trying to make this progressive moment in American history a success. So that's where I'm pushing."[105]

Krugman's columns have drawn criticism as well as praise. A 2003 article in The Economist[106] questioned Krugman's "growing tendency to attribute all the world's ills to George Bush," citing critics who felt that "his relentless partisanship is getting in the way of his argument" and claiming errors of economic and political reasoning in his columns.[83] Daniel Okrent, a former The New York Times ombudsman, in his farewell column, criticized Krugman for what he said was "the disturbing habit of shaping, slicing and selectively citing numbers in a fashion that pleases his acolytes but leaves him open to substantive assaults."[107][108]

Krugman's New York Times blog is "The Conscience of a Liberal," devoted largely to economics and politics.

Five days after 9/11 terrorist attacks Krugman argued in his column that calamity was "partly self-inflicted" due to transfer of responsibility for airport security from government to airlines. His column provoked an angry response and The New York Times was flooded with complaints. According to Larissa MacFarquhar of The New Yorker, while some people[who?] thought that he was too partisan to be a columnist for The New York Times, he was revered on the left.[109][110] Similarly, on the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 on the United States Krugman again provoked a controversy by accusing on his New York Times blog former U.S. President George W. Bush and former New York City major Rudy Giuliani of rushing "to cash in on the horror" after the attacks and describing the anniversary as "an occasion for shame".[111][112]

East Asian growth

In a 1994 Foreign Affairs article, Paul Krugman argued that it was a myth that the economic successes of the East Asian 'tigers' constituted an economic miracle. He argued that their rise was fueled by mobilizing resources and that their growth rates would inevitably slow.[113] His article helped popularize the argument made by Lawrence Lau and Alwyn Young, among others, that the growth of economies in East Asia was not the result of new and original economic models, but rather from high capital investment and increasing labor force participation, and that total factor productivity had not increased. Krugman argued that in the long term, only increasing total factor productivity can lead to sustained economic growth. Krugman's article was highly criticized in many Asian countries when it first appeared, and subsequent studies disputed some of Krugman's conclusions. However, it also stimulated a great deal of research, and may have caused the Singapore government to provide incentives for technological progress.[114]

During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Krugman advocated currency controls as a way to mitigate the crisis. Writing in a Fortune magazine article, he suggested exchange controls as "a solution so unfashionable, so stigmatized, that hardly anyone has dared suggest it."[115] Malaysia was the only country that adopted such controls, and although the Malaysian government credited its rapid economic recovery on currency controls, the relationship is disputed.[116] Krugman later stated that the controls might not have been necessary at the time they were applied, but that nevertheless "Malaysia has proved a point—namely, that controlling capital in a crisis is at least feasible."[117] Krugman more recently pointed out that emergency capital controls have even been endorsed by the IMF, and are no longer considered radical policy.[118]

U.S. economic policies

In the early 2000s, Krugman repeatedly criticized the Bush tax cuts, both before and after they were enacted. Krugman argued that the tax cuts enlarged the budget deficit without improving the economy, and that they enriched the wealthy – worsening income distribution in the US.[90][119][120][121][122] Krugman advocated lower interest rates (to promote spending on housing and other durable goods), and increased government spending on infrastructure, military, and unemployment benefits, arguing that these policies would have a larger stimulus effect, and unlike permanent tax cuts, would only temporarily increase the budget deficit.[122]

In August 2005, after Alan Greenspan expressed concern over housing markets, Krugman criticized Greenspan's earlier reluctance to regulate the mortgage and related financial markets, arguing that "[he's] like a man who suggests leaving the barn door ajar, and then – after the horse is gone – delivers a lecture on the importance of keeping your animals properly locked up."[123]

Krugman has repeatedly expressed his view that Greenspan and Phil Gramm are the two individuals most responsible for causing the subprime crisis. Krugman points to Greenspan and Gramm for the key roles they played in keeping derivatives, financial markets, and investment banks unregulated, and to the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which repealed Great Depression era safeguards that prevented commercial banks, investment banks and insurance companies from merging.[124][125][126][127]

Krugman has also been critical of some of the Obama administration's economic policies. He has criticized the Obama stimulus plan as being too small and inadequate given the size of the economy and the banking rescue plan as misdirected; Krugman wrote in The New York Times: "an overwhelming majority [of the American public] believes that the government is spending too much to help large financial institutions. This suggests that the administration's money-for-nothing financial policy will eventually deplete its political capital."[128] In particular, he considered the Obama administration's actions to prop up the US financial system in 2009 to be impractical and unduly favorable to Wall Street bankers.[108] In anticipation of President Obama's Job Summit in December 2009, Krugman said in a Fresh Dialogues interview, "This jobs summit can't be an empty exercise…he can't come out with a proposal for $10 or $20 Billion of stuff because people will view that as a joke. There has to be a significant job proposal…I have in mind something like $300 Billion."[129]

Krugman has recently criticized China's exchange rate policy, which he believes to be a significant drag on global economic recovery from the Late-2000s recession, and he has advocated a "surcharge" on Chinese imports to the US in response.[130] Jeremy Warner of The Daily Telegraph accused Krugman of advocating a return to self-destructive protectionism.[131]

In April 2010, as the Senate began considering new financial regulations, Krugman argued that the regulations should not only regulate financial innovation, but also tax financial-industry profits and remuneration. He cited a paper by Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny released the previous week, which concludes that most innovation was in fact about "providing investors with false substitutes for [traditional] assets like bank deposits," and once investors realize the sheer number of securities that are unsafe a "flight to safety" occurs which necessarily leads to "financial fragility."[132][133]

In his June 28, 2010 column in The New York Times, in light of the recent G-20 Toronto Summit, Krugman criticized world leaders for agreeing to halve deficits by 2013. Krugman claimed that these efforts could lead the global economy into the early stages of a "third depression" and leave "millions of lives blighted by the absence of jobs." He advocated instead the continued stimulus of economies to foster greater growth.[134]

Economic views

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

Krugman identifies as a Keynesian[135] and a saltwater economist,[4] and he has criticized the freshwater school on macroeconomics.[5][136] Though he applies New Keynesian theory in some of his work, he has also criticized it for lacking predictive power and for hewing to ideas like the efficient markets hypothesis and rational expectations.[136] Since the 1990s, he has promoted the IS-LM model as invented by John Hicks, pointing out its relative simplicity compared to New Keynesianism and continued currency in practical economic policy.[3][2][137]

In the wake of the 2007-2009 financial crisis he has remarked that he is "gravitating towards a Keynes-Fisher-Minsky view of macroeconomics."[138] Post-Keynesian observers cite commonalities between Krugman's views and those of the Post-Keynesian school.[139][140] [141] In recent academic work, he has collaborated with Gauti Eggertsson on a New Keynesian model of debt-overhang and debt-driven slumps, inspired by the writings of Irving Fischer, Hyman Minsky, and Richard Koo. Their work argues that during a debt-driven slump, the "paradox of toil", together with the paradox of flexibility, can exacerbate a liquidity trap, reducing demand and employment.[142]

Free trade

Krugman's views on free trade have provoked considerable ire from the anti-globalism movement.[143][144][20] He once famously quipped that, "If there were an Economist's Creed, it would surely contain the affirmations 'I understand the Principle of Comparative Advantage' and 'I advocate Free Trade'."[145][146] However, in the same article, Krugman argues[146] that, given the findings of New Trade Theory,

- ... free trade is not passé, but ... has irretrievably lost its innocence. Its status has shifted from optimum to reasonable rule of thumb...it can never again be asserted as the policy that economic theory tells us is always right. Nevertheless, Krugman declares in favor of free trade given the enormous political costs of actively engaging in strategic trade policy (i.e. rent-seeking) and because there is no clear method for a government to discover which industries will ultimately yield positive returns. In the same article, Krugman expressed that the phenomena of increasing returns (of which strategic trade policy depends) does not disprove the underlying truth behind comparative advantage.

Political views

Krugman describes himself as liberal, and has explained that he views the term "liberal" in the American context to mean "more or less what social democratic means in Europe."[91] In a 2009 Newsweek article, Evan Thomas described Krugman as having "all the credentials of a ranking member of the East coast liberal establishment" but also as someone who is anti-establishment, a "scourge of the Bush administration," and a critic of the Obama administration.[108] In 1996, Newsweek's Michael Hirsh remarked "Say this for Krugman: though an unabashed liberal ... he's ideologically colorblind. He savages the supply-siders of the Reagan-Bush era with the same glee as he does the 'strategic traders' of the Clinton administration."[100]

Krugman has advocated free markets in contexts where they are often viewed as controversial. He has written against rent control in favor of supply and demand,[147] likened the opposition against free trade and globalization to the opposition against evolution via natural selection,[143] opposed farm subsidies,[148] argued that sweatshops are preferable to unemployment,[41] dismissed the case for living wages,[149] argued against mandates, subsidies, and tax breaks for ethanol,[150] and questioned NASA's manned space flights.[151] Krugman has also criticized U.S. zoning laws[152] and European labor market regulation.[153][154]

U.S. race relations

Krugman has repeatedly criticized the Republican Party leadership for what he sees as a strategic (but largely tacit) reliance on racial divisions.[155][156][157] In his Conscience of a Liberal, he wrote

The changing politics of race made it possible for a revived conservative movement, whose ultimate goal was to reverse the achievements of the New Deal, to win national elections – even though it supported policies that favored the interests of a narrow elite over those of middle- and lower-income Americans.[158]

Krugman also once wrote in defense of Glenn Loury, a conservative black economist, that Loury, in defiance of many African-American political leaders,[159] had clearly seen and articulated that "the problems facing African-Americans had changed. The biggest barrier to progress was no longer active racism of whites but internal social problems of the black community."[160][161][162]

On working in the Reagan administration

Krugman worked for Martin Feldstein when the latter was appointed chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers and chief economic advisor to President Ronald Reagan. He later wrote in an autobiographical essay, "It was, in a way, strange for me to be part of the Reagan Administration. I was then and still am an unabashed defender of the welfare state, which I regard as the most decent social arrangement yet devised."[31] Krugman found the time "thrilling, then disillusioning". He did not fit into the Washington political environment, and was not tempted to stay on.[31]

On Gordon Brown vs David Cameron

Although Krugman includes Gordon Brown among those he considers at fault for the Late-2000s financial crisis,[163] he has also praised the former British Prime Minister, whom he described as "more impressive than any US politician" after a three-hour conversation with him.[164] Krugman asserted that Brown "defined the character of the worldwide financial rescue effort" and urged British voters not to support the opposition Conservative Party in the 2010 General Election, arguing their Party Leader David Cameron "has had little to offer other than to raise the red flag of fiscal panic."[165][166]

Controversies

Partisanship

In a 2003 article, The Economist noted that Krugman's critics argue that "his relentless partisanship is getting in the way of his argument". The Economist also wrote that the vast majority of Krugman's columns feature attacks on Republicans and almost none criticize Democrats, making him "a sort of ivory-tower folk-hero of the American left—a thinking person's Michael Moore".[17]

Libertarian conservative and federal appeals court judge Richard Posner called Krugman "an unabashed Democratic partisan who often goes overboard in his hatred of the Republicans."[167]

Liberal journalist and author Michael Tomasky in The New York Review of Books stated "Many liberals would name Paul Krugman of The New York Times as perhaps the most consistent and courageous—and unapologetic—liberal partisan in American journalism."[168] New York Magazine called Krugman "the leading exponent of a kind of liberal purism", while liberal historian Michael Kazin has opined that Krugman’s account of the right succumbed to the Marxist flaw of false consciousness.[169]

Economics and policy recommendations

Economist and former United States Secretary of the Treasury Larry Summers has stated Krugman has a tendency to favor more extreme policy recommendations because "it’s much more interesting than agreement when you’re involved in commenting on rather than making policy."[169]

According to Harvard professor of economics Robert Barro, Krugman "has never done any work in Keynesian macroeconomics" and makes arguments that are politically convenient for him.[170] In an interview with Businessweek, Nobel laureate Edward Prescott charged that Krugman "doesn't command respect in the profession", as "no respectable macroeconomist" believes that economic stimulus works; although the same article notes that economists who support such stimulus form "probably a majority".[171]

Enron

In early 1999, Krugman served on an advisory panel (including Larry Lindsey and Robert Zoellick) that offered Enron executives briefings on economic and political issues. He resigned from the panel in the fall of 1999 to comply with The New York Times rules regarding conflicts of interest, when he accepted the Times's offer to become an op-ed columnist.[172] Krugman later stated that he was paid $37,500 (not $50,000 as often reported - his early resignation cost him part of his fee), and that, for consulting that required him to spend four days in Houston, the fee was "rather low compared with my usual rates", which were around $20,000 for a one-hour speech.[172] He also stated that the advisory panel "had no function that I was aware of", and that he later interpreted his role as being "just another brick in the wall" Enron used to build an image.[173]

When the story of Enron's corporate scandals broke two years later, Krugman was accused of unethical journalism, specifically of having a conflict of interest.[174][175][176] Some of his critics claimed that "The Ascent of E-man," an article Krugman wrote for Fortune magazine[177] about the rise of the market as illustrated by Enron's energy trading, was biased by Krugman's earlier consulting work for them.[172] Krugman later argued that "The Ascent of E-Man" was in character, writing "I have always been a free-market Keynesian: I like free markets, but I want some government supervision to correct market failures and ensure stability."[172] Krugman noted his previous relationship with Enron in that article and in other articles he wrote on the company.[172][178] Krugman was one of the first to argue that deregulation of the California energy market had led to market manipulation by energy companies.[179]

In popular culture

Krugman appears as himself in a cameo in the 2010 comedy film Get Him to the Greek.[180] Loudon Wainwright III song The Krugman Blues[181], on the 2010 album 10 Songs For The New Depression, describes Wainwrights reading of Krugman's articles in The New York Times.

Published works

Academic books (authored or coauthored)

- The Spatial Economy – Cities, Regions and International Trade (July 1999), with Masahisa Fujita and Anthony Venables. MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-06204-6

- The Self Organizing Economy (February 1996), ISBN 1-55786-698-8

- EMU and the Regions (December 1995), with Guillermo de la Dehesa. ISBN 1-56708-038-3

- Development, Geography, and Economic Theory (Ohlin Lectures) (September 1995), ISBN 0-262-11203-5

- Foreign Direct Investment in the United States (3rd Edition) (February 1995), with Edward M. Graham. ISBN 0-88132-204-0

- World Savings Shortage (September 1994), ISBN 0-88132-161-3

- What Do We Need to Know About the International Monetary System? (Essays in International Finance, No 190 July 1993) ISBN 0-88165-097-8

- Currencies and Crises (June 1992), ISBN 0-262-11165-9

- Geography and Trade (Gaston Eyskens Lecture Series) (August 1991), ISBN 0-262-11159-4

- The Risks Facing the World Economy (July 1991), with Guillermo de la Dehesa and Charles Taylor. ISBN 1-56708-073-1

- Has the Adjustment Process Worked? (Policy Analyses in International Economics, 34) (June 1991), ISBN 0-88132-116-8

- Rethinking International Trade (April 1990), ISBN 0-262-11148-9

- Trade Policy and Market Structure (March 1989), with Elhanan Helpman. ISBN 0-262-08182-2

- Exchange-Rate Instability (Lionel Robbins Lectures) (November 1988), ISBN 0-262-11140-3

- Adjustment in the World Economy (August 1987) ISBN 1-56708-023-5

- Market Structure and Foreign Trade: Increasing Returns, Imperfect Competition, and the International Economy (May 1985), with Elhanan Helpman. ISBN 0-262-08150-4

Academic books (edited or coedited)

- Currency Crises (National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report) (September 2000), ISBN 0-226-45462-2

- Trade with Japan : Has the Door Opened Wider? (National Bureau of Economic Research Project Report) (March 1995), ISBN 0-226-45459-2

- Empirical Studies of Strategic Trade Policy (National Bureau of Economic Research Project Report) (April 1994), co-edited with Alasdair Smith. ISBN 0-226-45460-6

- Exchange Rate Targets and Currency Bands (October 1991), co-edited with Marcus Miller. ISBN 0-521-41533-0

- Strategic Trade Policy and the New International Economics (January 1986), ISBN 0-262-11112-8

Economics textbooks

- Economics: European Edition (Spring 2007), with Robin Wells and Kathryn Graddy. ISBN 0-7167-9956-1

- Macroeconomics (February 2006), with Robin Wells. ISBN 0-7167-6763-5

- Economics, first edition (December 2005), with Robin Wells. ISBN 1-57259-150-1

- Economics, second edition (2009), with Robin Wells. ISBN 0-7167-7158-6

- Microeconomics (March 2004), with Robin Wells. ISBN 0-7167-5997-7

- International Economics: Theory and Policy, with Maurice Obstfeld. 7th Edition (2006), ISBN 0-321-29383-5; 1st Edition (1998), ISBN 0-673-52186-9

Books for a general audience

- The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008 (December 2008) ISBN 0-393-07101-4

- An updated version of his previous work.

- The Conscience of a Liberal (October 2007) ISBN 0-393-06069-1

- The Great Unraveling: Losing Our Way in the New Century (September 2003) ISBN 0-393-05850-6

- A book of his The New York Times columns, many deal with the economic policies of the Bush administration or the economy in general.

- Fuzzy Math: The Essential Guide to the Bush Tax Plan (May 4, 2001) ISBN 0-393-05062-9

- The Return of Depression Economics (May 1999) ISBN 0-393-04839-X

- Considers the long economic stagnation of Japan through the 1990s, the Asian financial crisis, and problems in Latin America.

- The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008 (December 2008) ISBN 0-393-07101-4

- The Accidental Theorist and Other Dispatches from the Dismal Science (May 1998) ISBN 0-393-04638-9

- Essay collection, primarily from Krugman's writing for Slate.

- Pop Internationalism (March 1996) ISBN 0-262-11210-8

- Essay collection, covering largely the same ground as Peddling Prosperity.

- Peddling Prosperity: Economic Sense and Nonsense in an Age of Diminished Expectations (April 1995) ISBN 0-393-31292-5

- History of economic thought from the first rumblings of revolt against Keynesian economics to the present, for the layman.

- The Age of Diminished Expectations: U.S. Economic Policy in the 1990s (1990) ISBN 0-262-11156-X

- A "briefing book" on the major policy issues around the economy.

- Revised and Updated, January 1994, ISBN 0-262-61092-2

- Third Edition, August 1997, ISBN 0-262-11224-8

Selected academic articles

- (1998) 'It's Baaack: Japan's Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap' Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1998, pp. 137–205.

- (1996) 'Are currency crises self-fulfilling?' NBER Macroeconomics Annual 11, pp. 345–78.

- (1995) (with AJ Venables). "Globalization and the inequality of nations". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 110 (4): 857–880. doi:10.2307/2946642.

- (1991) 'Increasing returns and economic geography'. Journal of Political Economy 99, pp. 483–99.

- (1991) "Target zones and exchange rate dynamics". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 106 (3): 669–82. doi:10.2307/2937922.

- (1991) 'History versus expectations'. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106 (2), pp. 651–67.

- (1981) 'Intra-industry specialization and the gains from trade'. Journal of Political Economy 89, pp. 959–73.

- (1980) 'Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade'. American Economic Review 70, pp. 950–59.

- (1979) 'A model of balance-of-payments crises'. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 11, pp. 311–25.

- (1979) 'Increasing returns, monopolistic competition, and international trade'. Journal of International Economics 9, pp. 469–79.

See also

- Capitol Hill Baby-Sitting Co-op, popularized in Krugman's book, Peddling Prosperity

- List of economists

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

- List of newspaper columnists

References

- ^ a b Paul Krugman (August 10, 2011). "Dismal Thoughts". The Conscience of a Liberal. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (August 30, 2011). "Who You Gonna Bet On, Yet Again (Somewhat Wonkish)". Conscience of a Liberal (blog). New York Times. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul. "There's something about macro". MIT. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (July 29, 2009). "The lessons of 1979-82". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (September 23, 2009). "The freshwater backlash (boring)". The New York Times.

- ^ See inogolo:pronunciation of Paul Krugman.

- ^ London School of Economics, Centre for Economic Performance, Lionel Robbins Memorial Lectures 2009: The Return of Depression Economics. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ^ "About Paul Krugman". krugmanonline. W. W. Norton & Company. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Nobel Prize Committee, "The Prize in Economic Sciences 2008"

- ^ Note: Krugman modeled a 'preference for diversity' by assuming a CES utility function like that in A. Dixit and J. Stiglitz (1977), 'Monopolistic competition and optimal product diversity', American Economic Review 67.

- ^ a b Forbes, October 13, 2008, "Paul Krugman, Nobel"

- ^ a b "Economist Rankings at IDEAS – Top 10% Authors, as of March 2011". Research Papers in Economics. March 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ Davis, William L, Bob Figgins, David Hedengren, and Daniel B. Klein. "Economic Professors' Favorite Economic Thinkers, Journals, and Blogs," Econ Journal Watch 8(2): 126-146, May 2011.[1]

- ^ Rampell, Catherine. "Paul Krugman Short Biography". New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ The New York Times, "The Conscience of a Liberal." Retrieved August 6, 2009

- ^ Luskin, Donald (September 21, 2005). "Checkmate". National Review.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b "The one-handed economist", The Economist, November 13, 2003, retrieved August 10, 2011

- ^ Street, Paul. "Obama's Violin". Z Magazine . Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ^ Devine, J. (1998). "Globalization and the 'Universal Market'". New York: ASSA Annual Conference.

- ^ a b Dale, Leigh; Gilbert, Helen (2007). Economies of representation, 1790-2000: colonialism and commerce. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 200–201. ISBN 0754662578. "[Krugman and Obstfeld] seem to want to shame students into believing that there are no well-found arguments against coercing poor countries into free trade [....] poor logic and pernicious insensitivity."

- ^ Dunham, Chris (July 14, 2009). ""In Search of a Man Selling Krug"". Genealogywise.com. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (December 11, 2010). "Lawn Guyland Is America's Future". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ^ Associated Press, "Paul Krugman, LI Native, wins Nobel in economics",Newsday, October 14, 2008

- ^ MacFarquhar, Larissa (March 1, 2010). "THE DEFLATIONIST: How Paul Krugman found politics". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Paul Krugman, "Your questions answered", blog, January 10, 2003, Retrieved December 19, 2007

- ^ Paul Krugman, "About my son", The New York Times blog, December 19, 2007

- ^ Krugman, Paul (March 25, 2010). "David Frum, AEI, Heritage And Health Care". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Andrew Clark (May 29, 2011). "Paul Krugman: liberal loner who thinks Obama is spineless and Gordon Brown saved the world | Business | The Observer". London: Guardian. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Interview, U.S. Economist Krugman Wins Nobel Prize in Economics "PBS, Jim Lehrer News Hour", October 13, 2008, transcript Retrieved October 14, 2008

- ^ The New York Times, August 6, 2009, "Up Front: Paul Krugman"

- ^ a b c Incidents From My Career, by Paul Krugman, Princeton University Press, Retrieved December 10, 2008

- ^ a b c d Princeton Weekly Bulletin, October 20, 2008, "Biography of Paul Krugman", 98(7)

- ^ "Sources of international friction and cooperation in high-technology development and trade." National Academies Press, 1996, p. 190

- ^ Paul Krugman (December 13, 2009). "Paul Samuelson, RIP". New York Times.

One of the things Robin Wells and I did when writing our principles of economics textbook was to acquire and study a copy of the original, 1948 edition of Samuelson's textbook.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g Kristian Behrens, Frédéric Robert-Nicoud (2009), "Krugman's Papers in Regional Science: The 100 dollar bill on the sidewalk is gone and the 2008 Nobel Prize well-deserved", Papers in Regional Science, 88(2), pp467-489

- ^ Paul Krugman, March 11, 2008, The New York Times blog, "Economics: the final frontier"

- ^ Forbes, Oct. 13, 2008, Arving Panagiriya.

- ^ Note: Krugman modeled a 'preference for diversity' by assuming a CES utility function like that in Avinash Dixit and Joseph Stiglitz (1977), 'Monopolistic competition and optimal product diversity', American Economic Review 67.

- ^ P. Krugman (1981), 'Trade, accumulation, and uneven development', Journal of Development Economics 8, pp. 149-61.

- ^ "Bold strokes: a strong economic stylist wins the Nobel", The Economist, October 16, 2008.

- ^ a b In Praise of Cheap Labor by Paul Krugman, Slate, March 21, 1997

- ^ (He writes on p. xxvi of his book The Great Unraveling that "I still have the angry letter Ralph Nader sent me when I criticized his attacks on globalization.")

- ^ Strategic trade policy and the new international economics, Paul R. Krugman (ed), The MIT Press, p.18, ISBN 978-0-262-61045-2

- ^ "Honoring Paul Krugman" Economix blog of The New York Times, Edward Glaeser, October 13, 2008.

- ^ Krugman (1999) "Was it all in Ohlin?"

- ^ Krugman PR (2008), "Interview with the 2008 laureate in economics Paul Krugman", December 6, 2008. Stockholm, Sweden.

- ^ ""Currency Crises"". Web.mit.edu. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Sarno, Lucio (2002). The Economics of Exchange Rates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 245–264. ISBN 0521485843.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Craig Burnside, Martin Eichenbaum, and Sergio Rebelo (2008), "Currency crisis models", New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd ed.

- ^ "The International Finance Multiplier", P. Krugman, October 2008

- ^ "Global Economic Integration and Decoupling", Donald L. Kohn, speech at the International Research Forum on Monetary Policy, Frankfurt, Germany, 06-26-2008; from website for the Board of Governors for the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved 08-20-2009, June 26, 2008

- ^ Nayan Chanda, YaleGlobal Online, orig. from Businessworld February 8, 2008 "Decoupling Demystified"

- ^ "The myth of decoupling," Sebastien Walti, February 2009

- ^ "The International Finance Multiplier", The Conscience of a Liberal (blog), 10-05-2008. Retrieved 09-20-2009

- ^ Andrew Leonard, "Krugman: 'We are all Brazilians now'", "How the World Works", 10-07-2008

- ^ "Krugman: The International Finance Multiplier", Mark Thoma, Economist's View, 10-06-2008, [2]

- ^ "The geography of finance: after the storm", R O'Brien, A Keith, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, June 2009 2(2):245-265 doi:10.1093/cjres/rsp015 [3]

- ^ "Financial Deleveraging and the International Transmission of Shocks", research memo, MB Devereux, J Yetman, 05-19-2009.

- ^ Escaith, Hubert and Gonguet, Fabien, International Trade and Real Transmission Channels of Financial Shocks in Globalized Production Networks (May 22, 2009). [4]

- ^ KS Imai, R Gaiha, G Thapa, "Finance, Growth, Inequality and Hunger in Asia: Evidence from Country Panel Data in 1960-2006", University of Manchester Economics Discussion Papers 12-16-2008

- ^ "Global Imbalances and Global Governance", Philip Lane, Center of Economic Policy Research, European Commission, 02-17-2009

- ^ Har, Clement, Nagar, Venky and Petacchi, Paolo, "The Effect of Rational Capital Markets versus Regulatory Enforcement on the Valuation of Innovative Financial Assets" (March 2009). Paolo Baffi Centre Research Paper No. 2009-40. [5]

- ^ The 2008/2009 World Economic Crisis: What It Means for U.S. Agriculture, M. Shane, Economic Research Service, USDA Outlook, 03-29-2009 [6]

- ^ "Financial crisis in Asia and the Pacific Region: Its genesis, severity and impact on poverty and hunger", KS Imai, R Gaiha, G Thapa, University of Manchester Economics Discussion Papers EDP-0810 11-11-2008 [7]

- ^ Japanese fixed income markets: money, bond and interest rate derivatives, Jonathan Batten, Thomas A. Fetherston, Peter G. Szilagyi (eds.) Elsevier Science, November 30, 2006, ISBN 978-0-444-52020-3 p.137

- ^ Ben Bernanke, "Japanese Monetary Policy: a case of self-induced paralysis?", in Japan's financial crisis and its parallels to U.S. experience, Ryōichi Mikitani, Adam Posen (ed), Institute for International Economics, October 2000 ISBN 978-0-88132-289-7 p.157

- ^ "Some Observations on the Return of the Liquidity Trap", Scott Sumner, Cato Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Winter 2002).

- ^ Reconstructing Macroeconomics: Structuralist Proposals and Critiques of the Mainstream, Lance Taylor, Harvard University Press, p.159: "Kregel (2000) points out that there are at least three theories of the liquidity trap in the literature--Keynes own analyses [...] Hicks' [in] 1936 and 1937 [...] and a view that can be attributed to Fisher in the 1930s and Paul Krugman in latter days"

- ^ Paul Krugman. "Paul Krugman's Japan page". Web.mit.edu. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "It's Baaack: Japan's Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap", Paul R. Krugman, Kathryn M. Dominquez, Kenneth Rogoff. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 1998, No. 2 (1998), pp. 137-205

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (2000), "Thinking About the Liquidity Trap", Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, v.14, no.4, Dec 2000, pp 221-237.

- ^ "Reply to Nelson and Schwartz", Paul Krugman, Journal of Monetary Economics, v.55, no.4, pp 857-860 05-23-2008

- ^ Krugman, Paul (1999). "The Return of Depression Economics", p.70-77. W. W. Norton, New York ISBN 0-393-04839-X

- ^ "Japan's Trap", May 2008. [8] Retrieved 08-22-2009

- ^ "Further Notes on Japan's Liquidity Trap", Paul Krugman

- ^ Restoring Japan's economic growth, Adam Posen, Petersen Institute, September 1, 1998, ISBN 978-0-88132-262-0 , p.123,

- ^ "What is wrong with Japan?", Nihon Keizai Shinbun, 1997 [9]

- ^ Krugman, Paul (June 15, 2009). "Stay the Course". The New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ "Some Reasons Why a New Crisis Needs a New Paradigm of Economic Thought", Keiichiro Kobayashi, RIETI Report No.108, Research Institute of Economy, Trade & Industry (Japan), 07-31-2009

- ^ Catherine Rampell (October 13, 2008). "Paul Krugman Wins Economics Nobel - Economix Blog - NYTimes.com". Economix.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ Prize Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, October 13, 2008, Scientific background on the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2008, "Trade and Geography – Economies of Scale, Differentiated Products and Transport Costs"

- ^ Avinash Dixit, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Spring, 1993), pp. 173-188, In Honor of Paul Krugman: Winner of the John Bates Clark Medal, Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ^ a b c The Economist, November 13, 2003, "Paul Krugman, one-handed economist"

- ^ "Adam Smith Award". Nabe.com. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Mother Jones: Paul Krugman., August 7, 2005. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ^ Paul Krugman, 2004. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ^ "Citation presented by Linda Bell, Associate Professor of Economics". Haverford.edu. May 28, 2004. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Nobel Prize in Economics". Swedish Academy. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ "The Great Unraveling: Losing Our Way in the New Century". Powell's Books. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul, Rolling Stone. December 14, 2006, "The Great Wealth Transfer"

- ^ a b "Nobelpristagaren i ekonomi 2008: Paul Krugman", speech by Paul Krugman (Retrieved December 26, 2008) 00:43 "The title of The Conscience of a Liberal [...] is a reference to a book published almost 50 years ago in the United States called The Conscience of a Conservative by Barry Goldwater. That book is often taken to be the origin, the start, of a movement that ended up dominating U.S. politics that reached its first pinnacle under Ronald Reagan and then reached its full control of the U.S. government for most of the last eight years."

- ^ a b c Michael Tomasky, The New York Review of Books, November 22, 2007, "The Partisan"

- ^ Krugman, Paul. The Conscience of a Liberal, 2007, W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-06069-1 p. 182

- ^ Conscience of a Liberal, p.102

- ^ Conscience of a Liberal, p.108

- ^ October 17, 2007- Krugman "On Healthcare, Tax Cuts, Social Security, the Mortgage Crisis and Alan Greenspan", in response to Alan Greenspan's September 24 appearance with Naomi Klein on Democracy Now!

- ^ "Malefactors of Megawealth" David M. Kennedy

- ^ Foreign Policy (online), 26 June 2008

- ^ a b J. Peter Neary (2009), "Putting the 'New' into New Trade Theory: Paul Krugman's Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics", Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 111(2), pp217-250

- ^ a b c Hirsh, Michael (March 4, 1996). "A Nobel-Bound Economist Punctures the CW--and Not a Few Big-Name Washington Egos". Newsweek. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ ""China the financial nexus" - Krugman". Channel4.com. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Confessore, Nicholas (December 2002). "Comparative Advantage". The Washington Monthly. Retrieved February 5, 2007.

- ^ New Statesman, February 16, 2004, "NS Profile - Paul Krugman"

- ^ "Fresh Dialogues interview with Alison van Diggelen, November 2009". Freshdialogues.com. December 9, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ a b "Fresh Dialogues interview with Alison van Diggelen". Freshdialogues.com. December 9, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ (unattributed) (2003). "The one-handed economist". The Economist.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Okrent, Daniel (May 22, 2005). "13 Things I Meant to Write About but Never Did". The New York Times. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c Evan Thomas, Newsweek, April 6, 2009, "Obama's Nobel Headache"

- ^ Larissa MacFarquhar (March 1, 2010). "The Deflationist: How Paul Krugman found politics". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 05, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Paul Krugman (September 16, 2001). "Reckonings; Paying the Price". The Conscience of a Liberal. Retrieved October 05, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Paul Krugman (September 11, 2011). "The Years of Shame". The Conscience of a Liberal. Retrieved October 05, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Tim Mak (September 13, 2011). "Paul Krugman defenders attacked by conservative bloggers". The Politico. Retrieved October 05, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Krugman, Paul (December 1994). "The Myth of Asia's Miracle". Foreign Affairs. www.foreignaffairs.org. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ Van Den Berg, Hendrik (2006). International Trade and Economic Growth. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 98–105. ISBN 978-0765618030.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Krugman, Paul (September 7, 1998). "Saving Asia: It's Time To Get Radical The IMF plan not only has failed to revive Asia's troubled economies but has worsened the situation. It's now time for some painful medicine". Fortune. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ Landler, Mark (September 4, 1999). "Malaysia Wins Its Economic Gamble". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ "Capital Control Freaks: How Malaysia got away with economic heresy", Slate, September 27, 1999. Retrieved 08-25-2009

- ^ Krugman, Paul (March 4, 2010). "Malaysian Memories". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (March 21, 2003). "Who Lost the U.S. Budget?". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved June 24, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Dana, Will (March 23, 2003). "Voodoo Economics". Rolling Stone. rollingstone.com. Retrieved August 1, 2009.

- ^ Lehrke, Dylan Lee (October 9, 2003). "Krugman blasts Bush". The Daily of the University of Washington. dailyuw.com. Retrieved August 1, 2009.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul (October 7, 2001). "Fuzzy Math Returns". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved August 1, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Krugman, Paul (August 29, 2005). "Greenspan and the Bubble". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (March 24, 2008). "Financial Crisis Should Be at Center of Election Debate". Spiegel Online. Spiegel. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (March 24, 2008). "Taming the Beast". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (March 29, 2008). "The Gramm connection". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Lerer, Lisa (March 28, 2008). "McCain guru linked to subprime crisis". Politico. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Paul Krugman. "Behind the Curve". The New York Times. March 9, 2009.

- ^ "Fresh Dialogues interview with Alison van Diggelen, November 2009". Freshdialogues.com. November 13, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Paul Krugman (March 15, 2010). "Taking on China". The New York Times Company. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Jeremy Warner (March 19, 2010). "Paul Krugman, the Nobel prize winner who threatens the world". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (April 23, 2010). "Don't cry for Wall Street". The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ Shleifer, Andrei; Vishny, Robert; Gennaioli, Nicola (April 12, 2010). "Financial Innovation and Financial Fragility" (PDF). Retrieved April 27, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/28/opinion/28krugman.html The New York Times 6/28/2010

- ^ Krugman, Paul (October 16, 2009). Samuel Brittan's recipe for recovery.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Krugman, Paul. (2009-9-2). "How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (June 21, 2011). "Mr. Keynes and the Moderns" (PDF). VOX (originally for Cambridge conference commemorating the 75th anniversary of the publication of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money). Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (May 19, 2009). Actually existing Minsky.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Rezende, Felipe C. (August 18, 2009). "Keynes's Relevance and Krugman's Economics".

- ^ Conceicao, Daniel Negreiros (July 19, 2009). "Krugman's New Cross Confirms It: Job Guarantee Policies Are Needed as Macroeconomic Stabilizers".

- ^ Mitchell, Bill (July 18, 2009). "Nobel prize winner sounding a trifle modern moneyish".

- ^ Eggertsson, Gauti B.; Krugman, Paul (February 14, 2011), Debt, Deleveraging, and the Liquidity Trap: A Fisher-Minsky-Koo Approach (PDF)

- ^ a b "''Ricardo's difficult idea''". Web.mit.edu. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Glasbeek, H. J. (2002). Wealth by stealth: corporate crime, corporate law, and the perversion of democracy. Between The Lines. p. 258. ISBN 1896357415. "As E.P. Thompson once noted, there are always willing experts and opinion leaders, such as Friedman and Krugman, to give a patina of legitimacy to the claims of the powerful [with their] ill-concealed cheer-leading ...."

- ^ Dev Gupta, Satya (1997). The political economy of globalization. Springer. p. 61. ISBN 079239903X.

- ^ a b Krugman, Paul R. (1987). "Is Free Trade Passe?". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1 (2). American Economic Association: 131–144.

- ^ Reckonings; A Rent Affair, by Paul Krugman, The New York Times, June 7, 2000