York, Upper Canada: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 1.122.163.157 (talk) to last revision by Evil saltine. (TW) |

|||

| Line 193: | Line 193: | ||

==== Election riot, 1832 ==== |

==== Election riot, 1832 ==== |

||

{{rquote|right|Total Overthrow, and utter prostration of the Ryersonian Revolutionists in York – and “last dying speech and confession” of Wm. L. Mackenzie – The great meeting took place yesterday, and has resulted in the most signal and unequivocal defeat of the Yankee Republican party. The British constitutionalists carried every thing before them, and Mackenzie and his abettors are put down now and for ever.|Patriot 3 April 1832.}} |

{{rquote|right|Total Overthrow, and utter prostration of the Ryersonian Revolutionists in York – and “last dying speech and confession” of Wm. L. Mackenzie – The great meeting took place yesterday, and has resulted in the most signal and unequivocal defeat of the Yankee Republican party. The British constitutionalists carried every thing before them, and Mackenzie and his abettors are put down now and for ever.|Patriot 3 April 1832.}} |

||

Buoyed by large public displays of support following his re-election in January, 1832, William Lyon Mackenzie Mackenzie called for a public meeting in York on the 23rd of March, in the face of an increasingly well organized opposition, and threats of violence. Both supporters and opponents of Mackenzie gathered in front of the Court House at noon, when Sheriff [[William Botsford Jarvis]] granted the chair of the meeting to Dr. Dunlop, of the [[Canada Company]], rather than Reform MPP [[Jesse Ketchum]], the reformers’ choice, despite a reform majority. The tories then made short order of the meeting, passing a resolution in favour of the colonial administration, and adjourning. |

|||

Mackenzie’s supporters had, in the meanwhile, reassembled to the west in front of the jail, where they set about passing their own resolutions. Ketchum, Mackenzie, Morrison and others stood in a wagon to address the crowd, when twenty members of the Orange Order grabbed the wagon sending them flying. In an attempt to diffuse the growing tension, Sheriff Jarvis assembled the government supporters into a parade of 1,200 which marched off to government house in the west end to cheer Lieut. Governor Colborne, before returning to the Market Square. As they re-passed the Court House, they were joined by a group carrying an effigy of Mackenzie, who made their way to the Advocate office on Church St., which they began to pelt with stones. After burning the effigy of Mackenzie, a general skirmish ensued when the terrified printers fired a warning shot over the mob’s heads. A riot ensued that lasted the night.<ref>{{cite book|last=Wilton|first=Carol|title=Popular politics and political culture in Upper Canada, 1800-1850|year=2000|publisher=McGill-Queen's University Press|location=Kingston/Montreal|page=106}}</ref> |

|||

==== Grand Convention of Delegates, 1834 ==== |

|||

[[File:SharonTemple.jpg|thumb|right|[[Sharon Temple]] National Historic Site built by the Children of Peace]] |

|||

Mackenzie returned to Toronto from his London journey in the last week of August, 1833, to find his appeals to the British Parliament had been ultimately ineffective. At an emergency meeting of Reformers, [[David Willson (1778–1866)|David Willson]], leader of the [[The Children of Peace|Children of Peace]], proposed extending the nomination process for members of the House of Assembly they had begun in their village of [[Sharon, Ontario|Hope]] north of Toronto to all four Ridings of York (now York Region), and to establish a "General Convention of Delegates" from each riding in which to establish a common political platform. This convention could then become the core of a "permanent convention" or political party - an innovation not yet seen in Upper Canada. The organization of this convention was a model for the "Constitutional Convention" Mackenzie organized for the Rebellion of 1837, where many of the same delegates were to attend.<ref>{{cite book|last=Schrauwers|first=Albert|title='Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada|year=2009|publisher=University of Toronto Press|location=Toronto|pages=137–9}}</ref> |

|||

The Convention was held in the old Court House on 27 February 1834 with delegates from all four of the York ridings. The week before, Mackenzie published Willson's call for a "standing convention" (political party). The day of the convention, the Children of Peace led a "Grand Procession" with their choir and band (the first civilian band in the province) to the Old Court House. David Willson was the main speaker before the convention and "he addressed the meeting with great force and effect".<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Colonial Advocate|date=20, 27 Feb. 1834}}</ref> The convention nominated 4 Reform candidates, all of whom were ultimately successful in the election. The convention stopped short, however, of establishing a political party. Instead, they formed yet another Political Union. |

|||

==== Incorporation as city, 1834==== |

|||

[[File:1834 Act incorporating the City of Toronto.jpg|thumbnail|1834 Act incorporating the City of Toronto]] |

|||

In 1833, several prominent reformers had petitioned the House to have the town incorporated, which would also have made the position of magistrate elective. The tory-controlled House of Assembly struggled to find a means of creating a legitimate electoral system which might, nonetheless, minimize the chances of reformers being elected. The bill passed on 6 March 1834 and proposed two different property qualifications for voting. There was a higher qualification for the election of aldermen (who would also serve as magistrates), and a lower one for common councillors. Two aldermen and two councilmen would be elected from each city ward. This relatively broad electorate was offset by a much higher qualification for election to office, which essentially limited election to the wealthy much like the old Court of Quarter Sessions it replaced. The mayor was elected by the aldermen from among their number, and a clear barrier was erected between those of property who served as full magistrates, and the rest. Only 230 of the city’s 2,929 adult men met this stringent property qualification.<ref>{{cite book|last=Firth|first=Edith|title=The town of York, 1815-1834: a further collection of documents of early Toronto|year=1966|publisher=Champlain Society|location=Toronto|pages=lxviii-lxix|url=http://link.library.utoronto.ca/champlain/DigObj.cfm?Idno=9_96854&lang=eng&Page=0079&Size=3&query=firth,%20edith&searchtype=Author&startrow=1&Limit=All}}</ref> However, the Family Compact - and their member for Parliament Sheriff [[William Botsford Jarvis|William B. Jarvis]] in particular - alienated a large part of the city's construction tradesmen in late 1833. Left without pay, they held [[Work and labour organization in Upper Canada|Toronto's first strike]]. Jarvis had them arrested, and obstructed legislation that would protect their pay. As a result, there was a major landslide in the first city elections. The first mayor of Toronto was [[William Lyon Mackenzie]]. |

|||

==== Collapse of the Market Building ==== |

|||

The new reform dominated municipal council, under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie, first mayor, quickly set to work to correct the problems left unchecked by the old Court of Quarter Sessions. Unsurprisingly for "Muddy York", the new civic corporation made roads a priority. This ambitious road improvement scheme put the new council in a difficult position; good roads were expensive, yet the incorporation bill had limited the ability of the council to raise taxes. An inequitable taxation system placed an unfair burden on the poorer members of the community. Mackenzie decided to take the matter directly to the citizens and called a public meeting at the Market Square on 29 July 1834 "for six, that being the hour at which the Mechanicks and labouring classes can most conveniently attend without breaking on a day’s labour." Mackenzie met with organized resistance, as the newly resurrected "British Constitutional Society", with [[William H. Draper]] as president, tory aldermen Carfrae, Monro and Denison as vice-presidents, and common councilman and newspaper publisher [[George Gurnett]] as secretary, met the night before, and "from 150 to 200 of the most respectable portion of the community assembled and unanimously resolved to meet the Mayor upon his own invitation." Sheriff William Jarvis took over the meeting and interrupted Mayor Mackenzie "to propose to the Meeting a vote of censure on his conduct as Mayor." In the resulting pandemonium, the two sides agreed that they would hold a second meeting the next day. The Tories called the meeting for three in the afternoon so that the working class "mechanics" would not be able to attend. The inability of the mechanics to attend was their saving grace, for the meeting ended in a terrible tragedy when the packed gallery overlooking Market Square collapsed, pitching the onlookers into the butcher’s stalls below, killing four and injuring dozens.<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Patriot|date=1 Aug 1834}}</ref> The Tory press immediately placed the blame on Mackenzie, even though he didn't attend. The Toronto mechanics, ironically spared the carnage because of the hour at which the meeting was appointed, did not appear to be swayed by the tory press. In the October 1834 provincial elections, Mackenzie was overwhelmingly elected in the second riding of York; Sheriff William Jarvis, running in the city of Toronto, lost to reformer James Edward Small by the slim margin of 252 to 260 votes. |

|||

== Population == |

|||

=== Government officers === |

|||

=== Merchants === |

|||

=== Mechanics and Tradesmen === |

|||

{{main|Work and labour organization in Upper Canada}} |

|||

=== Women === |

|||

=== Blacks === |

|||

=== Growth === |

|||

However, Toronto was part of the regional division of [[York County, Ontario|York County]] from the late 18th century until the establishment of [[Metropolitan Toronto|Metro Toronto]] in 1954. After 1954, York County was the area north of [[Steeles Avenue]] and later renamed [[Regional Municipality of York|York Region]] in 1971. |

|||

York's population prior to the 1830s was primarily British (from Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland) with a few other European settlers (French, German and Dutch). |

|||

Fire services did not exist in York, so it was likely provided by local residents with buckets of water. Soldiers at nearby [[Fort York]] also assisted in fire fighting when needed. As for policing, there was no official police force. Public order was provided by able bodied male citizens were required to report for night duty as special constables for a fixed number of nights a year on the pain of fine or imprisonment in a system known as "watch and ward".<ref>[http://www.russianbooks.org/crime/cph3.htm HISTORY OF THE TORONTO POLICE PART 1: 1834 - 1860]. Russianbooks.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{Portal|Toronto}} |

|||

*{{Commons-inline|History of Toronto by year}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

*James G. Chewett, [http://archive.org/details/cihm_27521 "The Upper Canada almanac, and provincial calendar, for the year of Our Lord 1827: being the third after bissextile or leap year, and the eighth year of the reign of His Majesty [King G<nowiki>]</nowiki>eorge the Fourth ..."] (York (Toronto): Robert Stanton, 1827), 76, ii pp. |

|||

*James G. Chewett, [http://archive.org/details/cihm_42711 "The Upper Canada almanac and astronomical calendar for the year of Our Lord 1828: being bissextile or leap year and the ninth year of the reign of His Majesty King George the Fourth ..."] (York (Toronto): Robert Stanton, 1828), 76, ii pp. |

|||

*James G. Chewett, [http://archive.org/details/cihm_26326 "The Upper Canada almanac, and provincial calendar, for the year of Our Lord 1831: being the third after bissextile, or leap year, and the second year of the reign of His Majesty King William the Fourth ..."] (York (Toronto): Robert Stanton, 1831), 103, ii pp. |

|||

* John Ross Robertson, [http://archive.org/details/landmarkstoronto01robeuoft "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1893" Vol. 1] (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1894) |

|||

* John Ross Robertson, [http://archive.org/details/landmarkstoronto02robeuoft "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1894" Vol. 2] (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1895) |

|||

* John Ross Robertson, [http://archive.org/details/landmarkstoronto03robeuoft "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1898" Vol. 3] (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1898) |

|||

* John Ross Robertson, [http://archive.org/details/landmarkstoronto04robeuoft "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1904" Vol. 4 Churches] (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1904) |

|||

* John Ross Robertson, [http://archive.org/details/landmarkstoronto05robeuoft "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1908" Vol. 5] (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1908) |

|||

* John Ross Robertson, [http://archive.org/details/landmarkstoronto06robeuoft "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1914" Vol. 6] (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1914) |

|||

* Henry Scadding, [http://archive.org/details/ytorontoofoldcol00scad "Toronto of old: collections and recollections illustrative of the early settlement and social life of the capital of Ontario"] (Toronto: Adams, Stevenson & Co., 1873). |

|||

{{Toronto}} |

|||

{{coord|43|38|53|N|79|24|15|W|source:ptwiki_region:CA-ON_type:city|display=title}} |

|||

[[Category:History of Toronto]] |

|||

[[Category:Upper Canada]] |

|||

[[Category:Former cities in Canada]] |

|||

[[Category:1793 establishments in Upper Canada]] |

|||

Revision as of 10:12, 10 March 2014

This article contains too many pictures for its overall length. (January 2013) |

| History of Toronto | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Events | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1793 | 3 | — |

| 1796 | 600 | +19900.0% |

| 1812 | 1,460 | +143.3% |

| 1813 | 720 | −50.7% |

| 1825 | 1,600 | +122.2% |

| 1832 | 5,500 | +243.8% |

| 1834 | 9,250 | +68.2% |

| The population figures for York from 1796 to 1834 include people living in the surrounding areas of the town centre:[1] | ||

York was the name of Old Toronto between 1793 and 1834. It was the second capital of Upper Canada. It was established in 1793 by Governor John Graves Simcoe, with a new 'Fort York' on the site of the last French 'Fort Toronto'. He believed it would be a superior location for the capital of Upper Canada, which was then at Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake), as the new site would be less vulnerable to attack by the Americans. He renamed the location York after Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, George III's second son. York became the capital of Upper Canada on February 1, 1796, the year Governor Simcoe returned to Britain and was temporarily replaced by Peter Russell.

Early settlement and growth

When Europeans first arrived at the site of present-day Toronto, the vicinity was inhabited by the Huron tribes, who by then had displaced the Iroquois tribes that had occupied the region for centuries before c. 1500.[2] The name Toronto is likely derived from the Iroquois word tkaronto, meaning "place where trees stand in the water".[3] It refers to the northern end of what is now Lake Simcoe, where the Huron had planted tree saplings to corral fish. A portage route from Lake Ontario to Lake Huron running through this point, the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail, led to widespread use of the name.

French traders founded Fort Rouillé on the current Exhibition grounds in 1750, but abandoned it in 1759.[4] During the American Revolutionary War, the region saw an influx of British settlers as United Empire Loyalists fled for the unsettled lands north of Lake Ontario. In 1787, the British negotiated the Toronto Purchase with the Mississaugas of New Credit, thereby securing more than a quarter million acres (1000 km2) of land in the Toronto area.[5]

Geography

Much of early York was heavily wooded with the town developed along shoreline of Lake Ontario and up Lot Street or modern day Queen Street; from the Don River to Yonge Street. Later expansion of the town moved the boundaries further west of modern day Fleet Street and north near Dundas Street

The shoreline was likely sandy and parts sloping down to Lake Ontario. The original shoreline followed what is now Front Street. Everything now south of Front Street is the result of land fill. The Toronto Islands were still connected to the mainland. It was wooded, with marshes in what is now Ashbridge's Bay and the then natural mouth of the Don (Keating Channel did not exist yet). Other than Lake Ontario, other waterways into old town included the Don and the southern end of Garrison Creek. The climate of York was similar to that of modern Toronto, but a bit cooler given the lack of human influence on the state of the environment.

-

York Harbour, looking west from the mouth of the Don River, c. 1793

-

Toronto Harbour, 1793

-

Toronto Bay, 1818

-

Toronto Harbour in 1820 by Lt. Gov. Maitland

-

York from Gibraltar Point, Toronto Islands, 1828

-

Toronto Bay looking from Taylor's Wharf east towards Gooderham & Worts' windmill, 1835

-

Curling on the Don River, 1836

-

Curling in High Park, 1836

First Settlement

The first European settlement in York was tent in 1793, purchased by John Graves Simcoe and used by James Cook.[6]

Fort York

York was surveyed by the British Army with roads in a box grid format, while others conform to the geography of the town. In 1797 a garrison was built east of modern day Bathurst Street, on the east bank of Garrison Creek. To the west, north and east the town was surround by forests. York was attacked by American forces during the Battle of York, part of the War of 1812. It was occupied, pillaged and then partially burned down on April 27, 1813. Following several more U.S. raids over the summer, the British garrison returned to York and rebuilt the fortifications, most of which are still standing today. The British Army occupied Fort York from 1793 to the 1850s and transferred it to Canada.

Old & New Town

The Old Town of York was laid out in ten original blocks between today's Adelaide and Front streets (the latter following the shoreline) with the first church (St James Anglican), Town Hall and Wharf (named St Lawrence after the river) on the west and the first parliament buildings, blockhouse and windmill on the east. All land south of Lot Street (now Queen Street) was reserved for expansion of the Town or Fort by the government as 'the Commons'. North of Lot Street began the rural Township of York. It was divided into large 'park lots' where the city's moneyed elite built their estates, such as 'the Grange' and 'Moss park.' With time, some of these estate lots were subdivided, like the Macaulay family estate between Yonge St and Osgoode Hall (now Toronto City Hall) which became a working-class neighbourhood known as Macaulaytown.

The Town of York quickly outgrew the small original blocks, and the street grid was extended to the west as the New Town with larger blocks varying in width between today's Jarvis Street and Peter Street. This was soon extended farther to the west as the New Town Extension up to the Garrison Creek which divided the Town from the grounds of the Fort, around today's Walnut Street. The Town was also extended in the east along King Street (then a part of Kingston Road) to the Don River.

-

The Grange, 1817, estate of D'Arcy Boulton Jr, north of Queen, west of McCaul St.

-

Chewett Building, King and York Streets, designedby John George Howard, 1834.

-

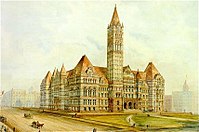

Toronto Jail (left), and court house (right) 1835

-

The Daniel Brooke Building, 1833 corner of Jarvis & King, opposite the market

-

Toronto's first Post Office, Adelaide St, next to the Bank of Upper Canada

-

Chief Justice William Campbell's house, 1822, Adelaide & Frederick St.

The Market & harbour

-

Second market building, King & Jarvis (later location of St Lawrence Hall)

-

Fish Market, Toronto, 1838 with Farmers' Storehouse in the background

-

Front St. Viewed from the wharf, 1841

Capital of Upper Canada

-

the third Parliament Building in York, 1832, on Front Street between Simcoe and John St.

-

Osgoode Hall, Queen & York St, in 1856

-

The Bank of Upper Canada Building in 1872 (Adelaide & George Street, Toronto)

-

Canada Company Office, 1807, King & Frederick St.

Schools & Churches

-

Upper Canada College, 1835, King St. between Simcoe and John St.

-

View of King St., looking east past the jail and court house at St James Anglican church.

-

St Andrew's Presbyterian Church, southwest corner Church and Adelaide Streets

Government & politics

Home District Council was responsible for municipal matters for York. In early years of the town matters was likely directed to the Executive Council of Upper Canada or the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada. All other matters were under the realm of the Colonial Office.

Family Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was noted for its conservatism and opposition to democracy.

Upper Canada did not have a hereditary nobility. In its place, senior members of Upper Canada bureaucracy, the Executive Council of Upper Canada and Legislative Council of Upper Canada, made up the elite of the Compact.[7] These men sought to solidify their personal positions into family dynasties and acquire all the marks of gentility. They used their government positions to extend their business and speculative interests.

The centre of the Compact was York. Its most important member was the Rev. John Strachan; many of the other members were his former students, or people who were related to him. The most prominent of Strachan's pupils was Sir John Beverley Robinson who was from 1829 the Chief Justice of Upper Canada for 34 years. The rest of the members were mostly descendants of United Empire Loyalists or recent upper-class British settlers such as the Boulton family, builders of the Grange.

-

John Robinson. Acknowledged leader of the Family Compact. Member of the Legislative Assembly and later the Legislative Council

-

Bishop John Strachan. Acknowledged Anglican leader of the Family Compact.

-

William Botsford Jarvis, Home District Sheriff

-

Col. James FitzGibbon, militia commander

-

William Henry Boulton 8th Mayor of Toronto and member of the Legislative Assembly

Reform opposition

Reform activity emerged in the 1830s when those suffering the abuses of the Family Compact began to emulate the organizational forms of the British Reform Movement, and organized Political Unions under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie. The British Political Unions had successfully petitioned for the Great Reform Act of 1832 that eliminated much of the political corruption in the English Parliamentary system. Prominent politicians in reform city politics included James Lesslie, a bookseller and founder of the Mechanics Institute, Bank of the People and House of Refuge & Industry; Jesse Ketchum, the Member of the Legislative Assembly for the city; Dr Thomas David Morrison, founder of the Upper Canada Political Union, and mayor of the city in 1836; and William O'Grady, publisher of the reform newspaper, The Correspondent.

-

Egerton Ryerson, leader of the Methodists

Political conflict

War of 1812

The Battle of York was fought on April 27, 1813. An American force supported by a squadron consisting of a ship-rigged corvette, a brig and twelve schooners landed on the lake shore to the west of the fort, defeating the British and capturing the fort, town and dockyard. The Americans suffered heavy casualties, including Brigadier General Zebulon Pike who was leading the troops when the retreating British blew up the fort's magazine. The American forces carried out several acts of arson and looting in the town before withdrawing. Though the Americans won a clear victory, it did not have decisive strategic results as York was a less important objective in military terms than Kingston, where the British armed vessels on Lake Ontario were based.

Types riot, 1826

In 1826, in the "Types Riot", the printing press of William Lyon Mackenzie was destroyed by the young lawyers of the Juvenile Advocate's Society with the complicity of the Attorney General, the Solicitor General and the magistrates of Toronto.

Mackenzie had published a series of satires under the pseudonym of "Patrick Swift, nephew of Jonathan Swift" in an attempt to humiliate the members of the Family Compact running for the board of the Bank of Upper Canada, and Henry John Boulton the Solicitor General, in particular. Mackenzie's articles worked, and they lost control. In revenge they sacked Mackenzie's press, throwing the type into the lake. The 'juvenile advocates' were the students of the Attorney General and the Solicitor General, and the act was performed in broad daylight in front of William Allan, bank president and magistrate. They were never charged, and it was left to Mackenzie to launch a civil lawsuit instead.

There are three implications of the Types riot according to historian Paul Romney. First, he argues the riot illustrates how the elite's self-justifications regularly skirted the rule of law they held out as their Loyalist mission. Second, he demonstrated that the significant damages Mackenzie received in his civil lawsuit against the vandals did not reflect the soundness of the criminal administration of justice in Upper Canada. And lastly, he sees in the Types riot “the seed of the Rebellion” in a deeper sense than those earlier writers who viewed it simply as the start of a highly personal feud between Mackenzie and the Family Compact. Romney emphasizes that Mackenzie’s personal harassment, the “outrage,” served as a lightning rod of discontent because so many Upper Canadians had faced similar endemic abuses and hence identified their political fortunes with his.[8]

See also: Mackenzie' own account

Election riot, 1832

Total Overthrow, and utter prostration of the Ryersonian Revolutionists in York – and “last dying speech and confession” of Wm. L. Mackenzie – The great meeting took place yesterday, and has resulted in the most signal and unequivocal defeat of the Yankee Republican party. The British constitutionalists carried every thing before them, and Mackenzie and his abettors are put down now and for ever.

— Patriot 3 April 1832.

Buoyed by large public displays of support following his re-election in January, 1832, William Lyon Mackenzie Mackenzie called for a public meeting in York on the 23rd of March, in the face of an increasingly well organized opposition, and threats of violence. Both supporters and opponents of Mackenzie gathered in front of the Court House at noon, when Sheriff William Botsford Jarvis granted the chair of the meeting to Dr. Dunlop, of the Canada Company, rather than Reform MPP Jesse Ketchum, the reformers’ choice, despite a reform majority. The tories then made short order of the meeting, passing a resolution in favour of the colonial administration, and adjourning.

Mackenzie’s supporters had, in the meanwhile, reassembled to the west in front of the jail, where they set about passing their own resolutions. Ketchum, Mackenzie, Morrison and others stood in a wagon to address the crowd, when twenty members of the Orange Order grabbed the wagon sending them flying. In an attempt to diffuse the growing tension, Sheriff Jarvis assembled the government supporters into a parade of 1,200 which marched off to government house in the west end to cheer Lieut. Governor Colborne, before returning to the Market Square. As they re-passed the Court House, they were joined by a group carrying an effigy of Mackenzie, who made their way to the Advocate office on Church St., which they began to pelt with stones. After burning the effigy of Mackenzie, a general skirmish ensued when the terrified printers fired a warning shot over the mob’s heads. A riot ensued that lasted the night.[9]

Grand Convention of Delegates, 1834

Mackenzie returned to Toronto from his London journey in the last week of August, 1833, to find his appeals to the British Parliament had been ultimately ineffective. At an emergency meeting of Reformers, David Willson, leader of the Children of Peace, proposed extending the nomination process for members of the House of Assembly they had begun in their village of Hope north of Toronto to all four Ridings of York (now York Region), and to establish a "General Convention of Delegates" from each riding in which to establish a common political platform. This convention could then become the core of a "permanent convention" or political party - an innovation not yet seen in Upper Canada. The organization of this convention was a model for the "Constitutional Convention" Mackenzie organized for the Rebellion of 1837, where many of the same delegates were to attend.[10]

The Convention was held in the old Court House on 27 February 1834 with delegates from all four of the York ridings. The week before, Mackenzie published Willson's call for a "standing convention" (political party). The day of the convention, the Children of Peace led a "Grand Procession" with their choir and band (the first civilian band in the province) to the Old Court House. David Willson was the main speaker before the convention and "he addressed the meeting with great force and effect".[11] The convention nominated 4 Reform candidates, all of whom were ultimately successful in the election. The convention stopped short, however, of establishing a political party. Instead, they formed yet another Political Union.

Incorporation as city, 1834

In 1833, several prominent reformers had petitioned the House to have the town incorporated, which would also have made the position of magistrate elective. The tory-controlled House of Assembly struggled to find a means of creating a legitimate electoral system which might, nonetheless, minimize the chances of reformers being elected. The bill passed on 6 March 1834 and proposed two different property qualifications for voting. There was a higher qualification for the election of aldermen (who would also serve as magistrates), and a lower one for common councillors. Two aldermen and two councilmen would be elected from each city ward. This relatively broad electorate was offset by a much higher qualification for election to office, which essentially limited election to the wealthy much like the old Court of Quarter Sessions it replaced. The mayor was elected by the aldermen from among their number, and a clear barrier was erected between those of property who served as full magistrates, and the rest. Only 230 of the city’s 2,929 adult men met this stringent property qualification.[12] However, the Family Compact - and their member for Parliament Sheriff William B. Jarvis in particular - alienated a large part of the city's construction tradesmen in late 1833. Left without pay, they held Toronto's first strike. Jarvis had them arrested, and obstructed legislation that would protect their pay. As a result, there was a major landslide in the first city elections. The first mayor of Toronto was William Lyon Mackenzie.

Collapse of the Market Building

The new reform dominated municipal council, under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie, first mayor, quickly set to work to correct the problems left unchecked by the old Court of Quarter Sessions. Unsurprisingly for "Muddy York", the new civic corporation made roads a priority. This ambitious road improvement scheme put the new council in a difficult position; good roads were expensive, yet the incorporation bill had limited the ability of the council to raise taxes. An inequitable taxation system placed an unfair burden on the poorer members of the community. Mackenzie decided to take the matter directly to the citizens and called a public meeting at the Market Square on 29 July 1834 "for six, that being the hour at which the Mechanicks and labouring classes can most conveniently attend without breaking on a day’s labour." Mackenzie met with organized resistance, as the newly resurrected "British Constitutional Society", with William H. Draper as president, tory aldermen Carfrae, Monro and Denison as vice-presidents, and common councilman and newspaper publisher George Gurnett as secretary, met the night before, and "from 150 to 200 of the most respectable portion of the community assembled and unanimously resolved to meet the Mayor upon his own invitation." Sheriff William Jarvis took over the meeting and interrupted Mayor Mackenzie "to propose to the Meeting a vote of censure on his conduct as Mayor." In the resulting pandemonium, the two sides agreed that they would hold a second meeting the next day. The Tories called the meeting for three in the afternoon so that the working class "mechanics" would not be able to attend. The inability of the mechanics to attend was their saving grace, for the meeting ended in a terrible tragedy when the packed gallery overlooking Market Square collapsed, pitching the onlookers into the butcher’s stalls below, killing four and injuring dozens.[13] The Tory press immediately placed the blame on Mackenzie, even though he didn't attend. The Toronto mechanics, ironically spared the carnage because of the hour at which the meeting was appointed, did not appear to be swayed by the tory press. In the October 1834 provincial elections, Mackenzie was overwhelmingly elected in the second riding of York; Sheriff William Jarvis, running in the city of Toronto, lost to reformer James Edward Small by the slim margin of 252 to 260 votes.

Population

Government officers

Merchants

Mechanics and Tradesmen

Women

Blacks

Growth

However, Toronto was part of the regional division of York County from the late 18th century until the establishment of Metro Toronto in 1954. After 1954, York County was the area north of Steeles Avenue and later renamed York Region in 1971.

York's population prior to the 1830s was primarily British (from Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland) with a few other European settlers (French, German and Dutch).

Fire services did not exist in York, so it was likely provided by local residents with buckets of water. Soldiers at nearby Fort York also assisted in fire fighting when needed. As for policing, there was no official police force. Public order was provided by able bodied male citizens were required to report for night duty as special constables for a fixed number of nights a year on the pain of fine or imprisonment in a system known as "watch and ward".[14]

See also

Media related to History of Toronto by year at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Toronto by year at Wikimedia Commons

References

- ^ List of E-STAT Census Tables and number of geographic areas by province Upper Canada / Ontario

- ^ See R. F. Williamson, ed., Toronto: An Illustrated History of its First 12,000 Years (Toronto: James Lorimer, 2008), ch. 2, with reference to the Mantle Site.

- ^ "The real story of how Toronto got its name". Natural Resources Canada (2005). Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ Fort Rouillé, Jarvis Collegiate Institute (2006). Retrieved on December 8, 2006.

- ^ Natives and newcomers, 1600–1793, City of Toronto (2006). Retrieved on December 8, 2006.

- ^ http://schools.tdsb.on.ca/jarvisci/toronto/tor1793.htm

- ^ W.S.Wallace, The Family Compact, Toronto 1915.

- ^ Romney, Paul (1987). "From the Types Riot to the Rebellion: Elite Ideology, Anti-legal Sentiment, Political Violence, and the Rule of Law in Upper Canada". Ontario History. LXXIX (2): 114.

- ^ Wilton, Carol (2000). Popular politics and political culture in Upper Canada, 1800-1850. Kingston/Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 106.

- ^ Schrauwers, Albert (2009). 'Union is Strength': W.L. Mackenzie, The Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 137–9.

- ^ Colonial Advocate. 20, 27 Feb. 1834.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Firth, Edith (1966). The town of York, 1815-1834: a further collection of documents of early Toronto. Toronto: Champlain Society. pp. lxviii–lxix.

- ^ Patriot. 1 August 1834.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ HISTORY OF THE TORONTO POLICE PART 1: 1834 - 1860. Russianbooks.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

External links

- James G. Chewett, "The Upper Canada almanac, and provincial calendar, for the year of Our Lord 1827: being the third after bissextile or leap year, and the eighth year of the reign of His Majesty [King G]eorge the Fourth ..." (York (Toronto): Robert Stanton, 1827), 76, ii pp.

- James G. Chewett, "The Upper Canada almanac and astronomical calendar for the year of Our Lord 1828: being bissextile or leap year and the ninth year of the reign of His Majesty King George the Fourth ..." (York (Toronto): Robert Stanton, 1828), 76, ii pp.

- James G. Chewett, "The Upper Canada almanac, and provincial calendar, for the year of Our Lord 1831: being the third after bissextile, or leap year, and the second year of the reign of His Majesty King William the Fourth ..." (York (Toronto): Robert Stanton, 1831), 103, ii pp.

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1893" Vol. 1 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1894)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1894" Vol. 2 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1895)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1898" Vol. 3 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1898)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1904" Vol. 4 Churches (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1904)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1908" Vol. 5 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1908)

- John Ross Robertson, "Landmarks of Toronto; a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1914" Vol. 6 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1914)

- Henry Scadding, "Toronto of old: collections and recollections illustrative of the early settlement and social life of the capital of Ontario" (Toronto: Adams, Stevenson & Co., 1873).