The Who: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Ritchie333 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

* [[Kenney Jones]]}} |

* [[Kenney Jones]]}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''The Who''' are an English [[Rock music|rock]] band that formed in 1964. Their best known line-up consisted of lead singer [[Roger Daltrey]], guitarist [[Pete Townshend]], bassist [[John Entwistle]] and drummer [[Keith Moon]]. They are considered one of the most influential rock bands of the 20th century |

'''The Who''' are an English [[Rock music|rock]] band that formed in 1964. Their best known line-up consisted of lead singer [[Roger Daltrey]], guitarist [[Pete Townshend]], bassist [[John Entwistle]] and drummer [[Keith Moon]]. They are considered one of the most influential rock bands of the 20th century.<ref name="BBC News">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-29374342|title=The Who unveil first new song in eight years|publisher=BBC|accessdate=26 Sep 2014}}</ref> |

||

The Who developed from an earlier group, the Detours, before stabilising around a line-up of Daltrey, Townshend, Entwistle and Moon. After releasing a single as the High Numbers, the group established themselves as part of the [[mod (subculture)|mod movement]] and featured [[auto-destructive art]] by destroying guitars and drums on stage. They achieved recognition in the UK after their first single as the Who, "[[I Can't Explain]]", reached the top ten. A string of successful singles followed, including "[[My Generation]]", "[[Substitute (The Who song)|Substitute]]" and "[[Happy Jack (song)|Happy Jack]]". Although initially regarded as a singles act, they also found success with the albums ''[[My Generation (album)|My Generation]]'' and ''[[A Quick One]]''. In 1967, they achieved success in the US after performing at the [[Monterey Pop Festival]], and with the top ten single "[[I Can See for Miles]]". They released ''[[The Who Sell Out]]'' at the end of the year, and spent much of 1968 touring. |

The Who developed from an earlier group, the Detours, before stabilising around a line-up of Daltrey, Townshend, Entwistle and Moon. After releasing a single as the High Numbers, the group established themselves as part of the [[mod (subculture)|mod movement]] and featured [[auto-destructive art]] by destroying guitars and drums on stage. They achieved recognition in the UK after their first single as the Who, "[[I Can't Explain]]", reached the top ten. A string of successful singles followed, including "[[My Generation]]", "[[Substitute (The Who song)|Substitute]]" and "[[Happy Jack (song)|Happy Jack]]". Although initially regarded as a singles act, they also found success with the albums ''[[My Generation (album)|My Generation]]'' and ''[[A Quick One]]''. In 1967, they achieved success in the US after performing at the [[Monterey Pop Festival]], and with the top ten single "[[I Can See for Miles]]". They released ''[[The Who Sell Out]]'' at the end of the year, and spent much of 1968 touring. |

||

Revision as of 12:44, 13 October 2014

The Who | |

|---|---|

The Who in 1975 Left to right: Roger Daltrey (vocals), John Entwistle (bass), Keith Moon (drums), Pete Townshend (guitar) | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | The Detours, The High Numbers |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres | Rock, hard rock, art rock, power pop, psychedelic rock |

| Years active | 1964–82, 1989, 1996–present (one-off reunions: 1985, 1988, 1990, 1991, 1994) |

| Labels | Brunswick, Reaction, Track, Polydor, Decca, MCA, Warner Bros., Universal Republic, Geffen, Atco |

| Members | |

| Past members | |

| Website | www |

The Who are an English rock band that formed in 1964. Their best known line-up consisted of lead singer Roger Daltrey, guitarist Pete Townshend, bassist John Entwistle and drummer Keith Moon. They are considered one of the most influential rock bands of the 20th century.[1]

The Who developed from an earlier group, the Detours, before stabilising around a line-up of Daltrey, Townshend, Entwistle and Moon. After releasing a single as the High Numbers, the group established themselves as part of the mod movement and featured auto-destructive art by destroying guitars and drums on stage. They achieved recognition in the UK after their first single as the Who, "I Can't Explain", reached the top ten. A string of successful singles followed, including "My Generation", "Substitute" and "Happy Jack". Although initially regarded as a singles act, they also found success with the albums My Generation and A Quick One. In 1967, they achieved success in the US after performing at the Monterey Pop Festival, and with the top ten single "I Can See for Miles". They released The Who Sell Out at the end of the year, and spent much of 1968 touring.

The group's fourth album, 1969's rock opera Tommy, was a major commercial and critical success. Subsequent live appearances at Woodstock and the Isle of Wight Festival, along with the live album Live At Leeds, transformed the Who's reputation from a hit-singles band into a respected rock act. With their success came increased pressure on lead songwriter Townshend, and the follow-up to Tommy, Lifehouse, was abandoned in favour of 1971's Who's Next. The group subsequently released Quadrophenia (1973) and The Who by Numbers (1975), oversaw the film adaptation of Tommy and toured to large audiences before semi-retiring from live performances at the end of 1976. The release of Who Are You in August 1978 was overshadowed by the death of Moon on 7 September.

Kenney Jones, formerly of the Small Faces and the Faces, replaced Moon and the group resumed touring. A film adaptation of Quadrophenia and the retrospective documentary The Kids Are Alright were released in 1979. The group continued recording, releasing Face Dances in 1981 and It's Hard the following year, before breaking up. They occasionally re-formed for live appearances such as Live Aid in 1985, a 25th anniversary tour in 1989 and for a tour of Quadrophenia in 1996. The Who resumed regular touring in 1999, with drummer Zak Starkey, to a positive response, and were considering the possibility of a new album, but these plans were stalled by Entwistle's death in June 2002. Townshend and Daltrey elected to continue as the Who, releasing Endless Wire (2006), which reached the top ten in the UK and US. The group continued to play live regularly, including the Quadrophenia and More tour in 2012, before announcing in 2014 their intention to retire from touring following a new album and accompanying live shows. However in October 2014 the group announced a massive 50th Anniversary tour to take place in 2015.

History

Background

The three founding members of the Who, Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend and John Entwistle, grew up in Acton, London. All three passed the Eleven plus exam and went to Acton County Grammar School.[2] Townshend's father, Cliff, played saxophone and his mother, Betty, had sung in the entertainment division of the Royal Air Force during World War II.[3] Entwistle's father, Herbert, played trumpet, and his mother, Queenie, played piano.[4] Townshend and Entwistle became friends in their second year of Acton County, and formed a trad jazz group, the Confederates,[5] while Entwistle also played french horn in the Middlesex Schools' Symphony Orchestra. Both became influenced by the increasing popularity of rock 'n' roll, and Townshend particularly admired Cliff Richard's debut single, "Move It".[6] Entwistle had decided to move to guitar as his instrument of choice, but after struggling with it due to his large fingers, and on hearing the guitar work of Duane Eddy, decided to move to the bass. He was unable to afford his own instrument and built one at home.[7][6] After Acton County, Entwistle went to work with the Inland Revenue, while Townshend started a course at Ealing Art College,[8] a move that he later described as profoundly influential on the course of the Who.[9]

Daltrey, who was in the year above them, had moved to Acton from Shepherd's Bush, a more working-class area. He had trouble fitting in at school, and discovered gangs and rock 'n' roll.[10] He was expelled from school aged 15 and found work on a building site.[11] Daltrey maintains that his subsequent musical career saved him from a dead-end working man's job,[10] and in 1959 he started the band that was to evolve into the Who. The band, called the Detours, played professional gigs from the very beginning, such as corporate and wedding functions, and Daltrey kept a close eye on the finances as well as the music.[12]

Daltrey met Entwistle by chance on the street, noticed he was carrying a bass, and recruited him into the Detours.[13] In the summer of 1961, Entwistle suggested Townshend as an additional guitarist.[13] The band played instrumentals by the Shadows and the Ventures, as well as a variety of pop and trad jazz covers. By the time Townshend was recruited, the line-up consisted of Daltrey as lead guitarist, Entwistle on bass, Harry Wilson on drums and Colin Dawson as vocalist.[14] Daltrey was considered the leader of the group and, according to Townshend, "ran things the way he wanted them".[9] Wilson was fired in the summer of 1962 in preference to Doug Sandom, who despite being significantly older than the rest of the band, and married, was a better musician, having been playing semi-professionally for two years at that point.[15] Dawson subsequently quit after frequently arguing with Daltrey.[9]

With the departure of Dawson, Daltrey moved to performing as lead vocalist, and Townshend, with Entwistle's encouragement, became the sole guitarist. Through Townshend's mother, the group obtained a management contract with local promoter Robert Druce[16] who started booking the band as a support act. The Detours became influenced by bands they were supporting, including Screaming Lord Sutch, Cliff Bennett and the Rebel Rousers, Shane Fenton and the Fentones, and Johnny Kidd and the Pirates. The Detours were particularly interested in the Pirates as they also only had one guitarist, Mick Green. Green inspired Townshend to take up a combined rhythm and lead guitar style, while Entwistle's bass became more of a lead instrument,[17] playing melodies. Entwistle would develop his bass technique throughout his career.[18] In February 1964, they became aware of the group Johnny Devlin and the Detours, so they decided to change their name.[19] Townshend and his room-mate Richard Barnes spent a night considering potential names, focusing on a theme of joke announcements, including "No One" and "The Group". Townshend preferred "the Hair", while Barnes liked "the Who" because it "had a pop punch".[20] Daltrey listened to suggestions the next morning and decided the Who was the best choice.[21]

1964–1978

Early career

By the time the Detours had changed their name to the Who, they had already found regular gigs, including at the Oldfield Hotel in Greenford, the White Hart Hotel in Acton, the Goldhawk Social Club in Shepherd's Bush, and the Notre Dame Hall in Leicester Square.[22] They had also replaced Druce as manager with Helmut Gorden, with whom they secured an audition with Chris Parmeinter for Fontana Records.[23] At the end of the audition, Parmeinter explained the drumming was a problem. According to Sandom, Townshend immediately turned on him and verbally assaulted him, threatening to fire him if his playing did not immediately improve. Sandom quit in disgust, but was persuaded to lend his kit to any potential stand-ins or replacements. Sandom and Townshend did not speak to each other again for 14 years.[24]

During a gig with a stand-in drummer in late April at the Oldfield, the band met Keith Moon for the first time. Unlike the other members, Moon grew up in Wembley, and had been drumming in bands since 1961.[25] At the time he was performing with a semi-professional band called the Beachcombers, but wanted to play in a band full-time.[26] Moon played a few songs with the group, breaking a bass drum pedal and tearing a drum skin in the process. The band were impressed with his energy and enthusiasm, and offered him the job.[27] Moon performed with the Beachcombers a few more times, but eventually a clash of dates occurred and he had no option but to devote himself full-time to the Who. The Beachcombers auditioned Sandom as a replacement, believing he left the Who due to a personality clash, but were unimpressed with his playing and declined.[28]

In the summer, the Who changed their manager to Peter Meaden. He decided that the group would be ideal to represent the growing mod movement in Britain which involved fashion, scooters and music genres such as rhythm and blues, soul, and beat music. He renamed the group the High Numbers, dressed them up in typical mod clothes,[29] secured a second, more favourable audition with Fontana and wrote the two sides for their single "Zoot Suit"/"I'm the Face" as an attempt to appeal to mods. Meaden had in fact merely written the lyrics, as the tune for "Zoot Suit" was "Misery" by the Dynamics,[30] while "I'm the Face" borrowed from Slim Harpo's "I Got Love If You Want It".[31] Although Meaden attempted to promote the single, it failed to reach the top 50[32] and the band reverted to calling themselves the Who.[33]

Meaden was replaced as manager by two film-makers, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp. They were looking for a young, unsigned rock group that they could make a film about,[34] and had seen the band playing at the Railway Hotel in Wealdstone, which had become a regular venue for them.[35][36] Lambert found affinity with Townshend in particular, due to his art school background, and encouraged him to write songs.[34] In August, Lambert and Stamp filmed a promotional film featuring the group and their audience at the Railway.[37] To highlight their music style, the band changed their set towards soul, rhythm and blues and Motown covers, and created the slogan "Maximum R&B".[29]

In June 1964, during a performance at the Railway, Townshend accidentally broke the head of his guitar on the low ceiling above the stage.[38] Angered by laughing from the audience, he smashed the instrument on the stage, then picked up another guitar and continued the show. The following week, the audience were keen to see a repeat of the event. Moon promptly obliged and kicked his drum kit over.[39] Subsequent auto-destructive art, as described by Townshend, became a feature of the Who's live set.[40][41] The incident at the Railway Hotel is one of Rolling Stone magazine's "50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock 'n' Roll".[42]

First singles and My Generation

By late 1964, the Who had started to become popular in London's Marquee club and a rave review of their live act appeared in Melody Maker.[43] Lambert and Stamp had managed to attract the attention of the American producer Shel Talmy, who had already found success by producing the Kinks. Townshend had written a song, "I Can't Explain", that deliberately sounded like the Kinks to attract Talmy's attention. Talmy saw the group in rehearsals and was impressed. He signed the group to his production company,[44] and sold the recording to the US arm of Decca Records, which meant that the group's early singles were released in Britain on Brunswick Records, one of UK Decca's labels for US artists.[45]

The single became popular with pirate radio stations such as Radio Caroline.[46] Pirate radio was important for bands during this time, as there were no commercial radios in the UK and the BBC Radio's output for pop music was extremely limited.[47] The group gained further popularity when they appeared on the television programme Ready Steady Go![29] Lambert and Stamp had been given the task of finding "typical teens", and invited the group's regular audience from the Goldhawk Social Club.[48] Their enthusiastic reception on television, aided by regular airplay on pirate radio, helped the single slowly climb the charts during early 1965, eventually reaching the top 10.[49] For the follow-up single, "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere", credited to both Townshend and Daltrey, Talmy arranged the use of guitar feedback, which was so unconventional that the US arm of Decca rejected the master tapes. The single reached the top 10 in the UK.[50]

The transition into a hit-making band with original material, eagerly encouraged by Lambert, did not sit well with Daltrey, particularly after a recording session of R&B covers went unreleased.[51] The Who were not particularly good friends either, apart from Moon and Entwistle, who enjoyed visiting nightclubs in the West End of London.[52] The group experienced a particularly fraught time when touring Denmark in September, which culminated in Daltrey throwing Moon's amphetamines down the toilet and physically assaulting him. Immediately on returning to Britain, Daltrey was sacked from the Who.[53] After a band meeting, he was reinstated on the strict condition that the group became a democracy without his dominant leadership. At the same time, the group enlisted Richard Cole as a roadie.[54]

The group recorded a follow-up single, "My Generation", in October. Townshend had written it as a slow blues, but after several abortive attempts, it was turned into a more powerful song with a bass solo from Entwistle.[55] It became the highest charting single the group have achieved to date, reaching No. 2.[56]: 12 The debut album My Generation (The Who Sings My Generation in the US) was released in late 1965. It included original material written by Townshend, including the title track and "The Kids Are Alright", as well as several James Brown covers that Daltrey favoured, from the aborted session earlier that year.[57]

After My Generation, the Who fell out with Talmy, which meant an abrupt end to their recording contract. Lambert and Stamp felt the royalty rate was poor,[58] while Talmy thought Lambert wanted to control recording sessions more. The resulting legal acrimony resulted in Talmy holding the rights to the master tapes, which prevented the album from being reissued. The dispute was finally resolved in 2002, when the album was remixed and reissued on CD.[59] Meanwhile, the Who were signed to Robert Stigwood's label, Reaction, and released "Substitute". Talmy took legal action over the B-side, "Instant Party", and so the single was withdrawn. A new B-side, "Waltz for a Pig", was recorded by the Graham Bond Organisation under the pseudonym "the Who Orchestra".[60]

Subsequent singles released in 1966 included "I'm a Boy", about a boy dressed as a girl, taken from an abortive collection of songs called Quads,[61] "Happy Jack",[62] and an EP, Ready Steady Who, that tied in with their regular appearances on Ready Steady Go![63]

A Quick One and The Who Sell Out

To alleviate financial pressure on the band, Lambert arranged a song-writing deal which required each member to write two songs for the next album. Entwistle contributed "Boris the Spider" and "Whiskey Man" and found a niche role as second songwriter,[64] but after recording the material, they found they needed to fill an extra ten minutes. Lambert encouraged Townshend to write a longer piece, which became "A Quick One, While He's Away". The album was subsequently titled A Quick One[65] (released as Happy Jack in the US),[66] and reached No. 4 in the charts.[67] It was followed in 1967 by the UK Top 5 single "Pictures of Lily."[68]

By 1966, Ready Steady Go! had stopped being broadcast, mod was in decline, and the Who found themselves in competition with groups including Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience on the London gigging circuit.[69] Lambert and Stamp realised that commercial success in the US was paramount to the group's future, and so arranged a deal with promoter Frank Barsalona for a short package tour in New York.[70] The group's performances, which still involved smashing guitars and kicking over drums, were well received,[71] and led to their first major US appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival. The group, especially Moon, were not fond of the hippie movement, but thought their violent stage act would stand in sharp contrast to the peaceful atmosphere of the festival. Hendrix was also on the bill, and decided he would also smash his guitar onstage. Townshend verbally abused Hendrix and accused him of stealing his act,[72] and the pair argued about who should go on stage first, with the Who winning the argument.[73] The Who brought hired equipment to the festival, while Hendrix shipped over his regular touring gear from Britain, including a full Marshall stack. According to biographer Tony Fletcher, Hendrix was "so much better than the Who it was embarrassing." Nevertheless, the Who's appearance at Monterey gave them recognition in the US, and led to "Happy Jack" reach the top 30.[74]

Immediately after Monterey, the group toured the US, supporting Herman's Hermits.[74] Though the Hermits were a straightforward pop band, the group members enjoyed drugs and practical jokes, and bonded with Moon,[75] who was excited to learn that cherry bombs were legal to purchase in Alabama. Moon acquired a reputation of destroying hotel rooms while on tour,[71] with a particular interest in blowing up toilets. Entwistle said the first cherry bomb they tried "blew a hole in the suitcase and the chair" while Moon, recalling his first attempt to flush one down the toilet, "all that porcelain flying through the air was quite unforgettable. I never realised dynamite was so powerful."[76] After a gig in Flint, Michigan on 23 August 1967 (Moon's 21st birthday), the entourage caused $24,000 of damage at the hotel, while Moon knocked out one of his front teeth.[77] Daltrey later said that the tour brought the band closer, and because they were only the support act, they could simply turn up and perform a short show without any major responsibilities.[78]

After the Hermits tour, the Who finished work on their next single, "I Can See for Miles". Townshend wrote the song in 1966, but had avoided recording it until he was sure that it could be produced well.[79] The single reached No. 10 in the UK, which disappointed Townshend, who called it "the ultimate Who record",[80] and became their best selling single in the US, reaching No. 9.[68] The group then set out to tour the US again with Eric Burdon and the Animals, including an appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, miming to "I Can See For Miles" and "My Generation".[81] Moon bribed a stage hand to put explosives in his drum kit, loading it with ten times the expected dose. The resulting detonation threw Moon off his drum riser while his arm was cut by flying cymbal shrapnel. Townshend's hair was fried and his left ear left ringing, while a camera and studio monitor were destroyed by a blast.[82]

The next album was The Who Sell Out—a concept album paying tribute to British pirate radio, which had been outlawed in August 1967 due to the Marine, &c., Broadcasting (Offences) Act 1967. It included several humorous jingles and mock commercials between songs,[83] a mini rock opera called "Rael" whose closing theme was reused for "Sparks" and "Underture" on Tommy, and "I Can See For Miles".[80] Later that year, Lambert and Stamp formed their own record label, Track Records, with distribution by Polydor. As well as signing Hendrix, Track became the imprint for all the Who's UK output until the mid-1970s.[84]

The group started 1968 with a tour of Australia and New Zealand with the Small Faces.[85] The groups had trouble with the local authorities and the New Zealand Truth called them "unwashed, foul-smelling, booze-swilling no-hopers".[86] They continued to tour across the US and Canada during the spring and summer.[87]

Tommy, Woodstock and Live at Leeds

By 1968, the Who had started to attract attention in the underground press.[88] Townshend had stopped using drugs by this point, and became interested in the teachings of Meher Baba.[89] In August, he gave a major interview to Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner describing a new album project. He described the plot and its relationship to Baba's teachings in intricate detail. The album went through several names during recording, including Deaf Dumb and Blind Boy and Amazing Journey, but Townshend eventually settled on Tommy.[90] The basic concept was to describe the life of a deaf, dumb and blind boy, and his attempt to communicate with others.[91][92] Some songs, such as "Welcome" and "Amazing Journey" were inspired by Baba's teaching,[93] while others came from observations within the band. "Sally Simpson" was written about a fan trying to climb on stage at a gig by the Doors that they attended[94] and "Pinball Wizard" was written so that New York Times journalist Nik Cohn, a pinball enthusiast, would give the album a good review.[95] Townshend later said "I wanted the story of Tommy to have several levels ... a rock singles level and a bigger concept level", containing the spiritual message he wanted as well as being entertaining.[96]

By the end of the year, 18 months of continuous touring had led to a well-rehearsed and tight live band, which was evident when they performed "A Quick One While He's Away" at The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, a planned television special. The Stones considered their own performance lacklustre, and the project was shelved and never broadcast.[97] The Who had not released an album in over a year, and had not completed the recording of Tommy, which continued well into 1969.[98] Lambert was a key figure in keeping the group focused and the album completed, and typed up a script to help them understand the story and how the songs fitted together.[99]

The album was released in May with the accompanying single, "Pinball Wizard", and a début performance at Ronnie Scott's,[101] after which the group set out on tour, playing most of the new album live.[102] The album was an immediate success, selling 200,000 copies in the first two weeks of release in the US.[103] In addition to commercial success, Tommy became a critical smash, Life saying, "... for sheer power, invention and brilliance of performance, Tommy outstrips anything which has ever come out of a recording studio".[104] Melody Maker declared: "Surely the Who are now the band against which all others are to be judged."[105] Daltrey's singing had become significantly better, and it translated well into performing the new material. He had grown his hair and tended to wear open shirts on stage, and this set the template for rock singers in the 1970s.[100] Townshend, meanwhile, had taken to wearing a boiler suit and Doctor Martens on stage.[100]

In August, the Who performed at the Woodstock Festival, despite being reluctant to do so and only agreeing after being paid $13,000 up front.[106] Originally scheduled to appear at 10pm on Saturday, 16 August,[107] the festival ran late and the group did not take to the stage until 5am on Sunday,[108] where they played most of Tommy.[109] During their performance, Yippie leader Abbie Hoffman interrupted the set to give a political speech about the arrest of John Sinclair, before Townshend kicked him off stage,[106] shouting: "Fuck off my fucking stage!"[110][108] During "See Me, Feel Me", the sun rose almost as if on cue[111] (Entwistle later said "God was our lighting man"),[110] while at the very end of the set, Townshend threw his guitar into the audience.[111][112] The set was professionally recorded and filmed, and portions of it appeared on the Woodstock film, The Old Grey Whistle Test and The Kids Are Alright.[113]

While Woodstock in general has been regarded as culturally significant, the Who have been critical of the event. Roadie John "Wiggie" Wolff, who arranged the band's payment, described the event as "a shambles",[107] while Daltrey declared it as "the worst gig we ever played"[114] and Townshend said, "I thought the whole of America had gone mad."[108] A more favourable appearance came a few weeks later at the second Isle of Wight Festival, which Townshend later described as "a great concert for us".[115]

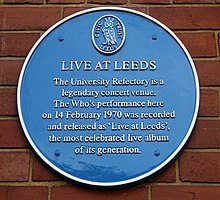

By 1970, the Who were widely considered to be one of the best and most popular live rock bands, with Chris Charlesworth describing concerts as "leading to a kind of rock nirvana that most bands can only dream about".[56]: 5 They decided a live album would help demonstrate how different the sound at their gigs was to Tommy, and set about listening to the hours of recordings they had accumulated. Townshend baulked at the prospect of doing so, and insisted that all the tapes should be burned. Instead, they booked two shows, one in Leeds on 14 February, and one in Hull the following day, with the specific intention of recording them for a live album. Technical problems from the Hull gig resulted in the Leeds gig being used, which became Live at Leeds.[56]: 5 The album is viewed by several critics as being one of the best live rock albums of all time, including The Independent,[116][117] The Telegraph[118] Rolling Stone[119] and the BBC.[120] The original album contained six songs, taken from the middle and end of the set, and has been reissued several times in expanded and remastered versions, which remedy technical problems and contain the performance of Tommy, as well as renditions of earlier singles.[121]

The Leeds University gig was part of the Tommy tour, which not only included shows in European opera houses but saw the Who become the first rock act to play at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City.[122] In March the Who released the UK top 20 hit "The Seeker", continuing a theme of issuing singles separate to albums. Townshend wrote the song to commemorate the common man, as a contrast to the themes on Tommy.[123]

Lifehouse and Who's Next

The success of Tommy secured the Who's future, and made them millionaires. The group reacted in different ways—Daltrey and Entwistle lived comfortably, Townshend was embarrassed at his wealth, which he felt at odds with Meher Baba's ideals, while Moon spent frivolously.[124] Entwistle had accumulated a backlog of songs that had not made it onto any Who album, and became the first member of the group to release a solo album, Smash Your Head Against the Wall, in May 1971.[125][126]

During the latter part of 1970, Townshend planned how the Who could make a studio album to follow up Tommy. He came up with Lifehouse, which was designed to be a multi-media project symbolising the relationship between an artist and his audience.[127] He developed numerous ideas in his home studio, creating various layers of synthesizers,[128] and the Young Vic theatre in London was booked for a series of experimental concerts. Townshend approached the gigs with optimism; the rest of the band were just happy to be gigging again.[129] Eventually, the others confronted Townshend, complaining the project was too complicated and they should simply record another album. Things deteriorated to the point that Townshend had a nervous breakdown, and Lifehouse was abandoned.[130][131]

In March 1971, the Who began recording the material written for Lifehouse with Kit Lambert at the Record Plant, New York City. Lambert produced the sessions, but was unproductive as he had acquired a heroin habit, and recording was eventually abandoned.[131] The group restarted the sessions with Glyn Johns in April.[133] Selections from the material, with one unrelated song ("My Wife") by Entwistle, were released as a traditional studio album, Who's Next in August.[134] The album became their most successful among critics and fans, reaching No. 1 in the UK and No. 1 in the US. Two tracks from the album, "Baba O'Riley" and "Won't Get Fooled Again", are early examples of synthesizer use in rock music; both tracks' keyboard sounds were generated in real time by a Lowrey organ, while on "Won't Get Fooled Again", it was further processed through a VCS3 synthesizer.[133] "Baba O'Riley" also featured a violin solo by Dave Arbus.[135] The Who continued to issue Lifehouse-related material over the next few years, including the singles "Let's See Action", "Join Together" and "Relay".[136][137][138]

Following the success of Who's Next, the band went back on tour, replacing much of the old Tommy material with the new songs.[139] In November they performed at the newly opened Rainbow Theatre in London for three nights,[140] continuing in the US later that month. Robert Hilburn of Los Angeles Times described the Who as "the Greatest Show on Earth".[141] The tour was slightly disrupted at the Civic Auditorium in San Francisco on 12 December, when Moon passed out over his kit after an overdose of brandy and barbiturates.[142] He recovered and completed the gig, playing to his usual strength.[143]

Quadrophenia, Tommy film and The Who by Numbers

After touring Who's Next, and needing time to write a follow-up, Townshend insisted that the Who take a lengthy break as they had not stopped touring since the band started.[145] There was no group activity until May 1972, when they started working on a proposed new album, Rock is Dead – Long Live Rock, [146] but the results were uninspired, and the sessions were abandoned. Tensions began to emerge between the group members—Townshend believed Daltrey just wanted a money-making band; Daltrey, conversely, thought Townshend's projects were getting pretentious. In addition, Moon's behaviour was becoming increasingly destructive and problematic through excessive drink and drugs use, and a continuous desire to party and tour.[147] Daltrey had also performed an audit of the group's finances and discovered that Lambert and Stamp had not kept sufficient records. He believed them to be no longer effective as managers, which Townshend and Moon disputed.[148] Following a short European tour, the remainder of 1972 was spent working on an orchestral version of Tommy, with Daltrey and Townshend collaborating with Lou Reizner.[149]

By 1973, the Who had decided to record an album called Quadrophenia about mod and its subculture, set against clashes with Rockers in early 1960s Britain (particularly at Brighton).[150] The story is about a boy named Jimmy, who undergoes a personality crisis, and the narrative details the relationship with his family, friends and mod culture.[151] By the time the album was being recorded, relationships between the band and Lambert and Stamp had broken down irreparably, and Bill Curbishley replaced them as manager.[152] Townshend played a variety of multi-tracked synthesizers, and Entwistle played several overdubbed horn parts.[153] The album became their highest charting cross-Atlantic success, peaking at No. 2 in both the UK and US.[154]

The tour for the album started in Stoke on Trent in October,[155] but was immediately beset with problems. Having successfully played "Baba O'Riley" and "Won't Get Fooled Again" live over a backing tape of the synthesizer parts, Townshend had assembled a variety of similar tapes for Quadrophenia. Unfortunately, the technology was not sophisticated enough to deal with the demands of the music, and rehearsals were interrupted due to an argument which culminated in Daltrey punching Townshend and knocking him out cold.[156] At a gig in Newcastle, the tapes completely malfunctioned, and an enraged Townshend dragged sound-man Bob Pridden on-stage, screamed at him, kicked all the amps over and partially destroyed the backing tapes. The show was abandoned in place of an "oldies" set, at the end of which Townshend smashed his guitar and Moon kicked over his drumkit.[157][156] A report in The Independent described this gig as one of the worst of all time.[158] The US tour started on 20 November at the Cow Palace, Daly City, California, where Moon passed out during "Won't Get Fooled Again" and, after a break backstage, again during "Magic Bus". Townshend asked the audience, "Can anyone play the drums?—I mean somebody good." An audience member, Scot Halpin, filled in for the rest of the show.[159][158] After a show in Montreal, the band (except for Daltrey, who retired to bed early) caused so much destruction to their hotel room, including destroying an antique painting and ramming a marble table through a wall, that the federal law enforcement was called, and they were arrested.[160]

By 1974, work had begun in earnest on a Tommy film. Stigwood suggested Ken Russell as director, whose previous work Townshend had admired.[161] The film featured a star-studded cast, including the band members themselves. David Essex auditioned for the title role, but the band persuaded Daltrey to take it.[162] The other cast members included Ann-Margret, Oliver Reed, Eric Clapton, Tina Turner, Elton John and Jack Nicholson.[163] Townshend and Entwistle worked on the film soundtrack for most of the year, handling the bulk of the instrumentation, but as Moon had moved to Los Angeles, they used Kenney Jones and Tony Newman as drummers. Phil Chen played some bass on the album, Nicky Hopkins and Chris Stainton handled some keyboards and Ronnie Wood, Mick Ralphs and Caleb Quaye guested on guitar. Elton John insisted on using his own band when recording "Pinball Wizard".[164] Filming began in April 1974 (including 1500 extras at Portsmouth Polytechnic for the "Pinball Wizard" sequence)[165] and carried on until August.[166]

The film premièred on 18 March 1975, to a standing ovation from the audience.[167] Ann-Margret received a Golden Globe Award for her performance, and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress.[168] Townshend was also nominated for an Oscar for his work in scoring and adapting the music for the film.[169] Tommy was shown at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival, but was not entered into the main competition.[170] It won the award for Rock Movie of the Year in the First Annual Rock Music Awards[171] and was a commercial success, generating over $2M in box-office receipts in its first month.[167] The soundtrack was also successful, reaching No. 2 on the Billboard albums chart.[172]

Because work on Tommy took up most of 1974, live performances by the Who were restricted to a one-off show in May at the Valley, the home of Charlton Athletic, in front of 80,000 fans[173] and a few dates at Madison Square Garden in June.[174] Towards the end of the year, the group released the out-takes album Odds & Sods, which featured several songs from the aborted Lifehouse project that had been compiled by Entwistle.[175]

Their 1975 album, The Who by Numbers, had introspective songs from Townshend that dealt with disillusionment such as "However Much I Booze" and "How Many Friends", Entwistle's "Success Story" that gave a humorous look at the music industry, and the hit single "Squeeze Box".[176] The group set out on tour in October, playing little new material, removing most of the Quadrophenia numbers and reintroducing several numbers from Tommy back into the set.[177] On 6 December 1975, the Who set the record for largest indoor concert at the Pontiac Silverdome, attended by 78,000 fans.[178] On 31 May 1976, they played a second concert at the Valley which was listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the world's loudest concert, at over 120 dB.[104] Townshend had become fed up of touring by this point[179] but Entwistle considered live performances to be at their peak at this time.[180]

Who Are You and Moon's death

After the 1976 tour, Townshend insisted on having most of the following year off to spend time with his family.[181] He discovered that former Beatles and Rolling Stones manager Allen Klein had managed to buy a stake in his publishing company. A settlement was reached, but Townshend was upset and disillusioned that Klein had attempted to force ownership of his songs. Townshend went to the Speakeasy where he met the Sex Pistols' Steve Jones and Paul Cook, who both liked the Who. After leaving the club, he passed out in a doorway, where a policeman said he would not be arrested if he could stand and walk. The events inspired the title track of the next album, Who Are You.[182]

The group reconvened in September 1977, but Townshend announced there would be no live performances for the immediate future, a decision that Daltrey endorsed. By this point, Moon was so unfit that the Who conceded it would be difficult for him to cope with touring. The only live gig performed that year was an informal show at the Gaumont State Cinema in Kilburn, London, on 15 December, as part of an upcoming documentary film about the band, The Kids Are Alright.[183] The band had not played for 14 months, and their performance was so weak that the footage was left unused. Moon's playing was particularly lacklustre and he had gained a lot of weight,[184] though Daltrey later said "even at his worst, Keith Moon was amazing."[185]

Recording of Who Are You started in January 1978. Daltrey clashed with Johns over the production of his vocals, and Moon's drumming was so poor that Daltrey and Entwistle considered firing him. Moon's playing subsequently improved, but on one track, "Music Must Change", he was absent entirely.[186] In May, the Who were required to film another performance at Shepperton Sound Studios in May for The Kids Are Alright, due to the poor performance at Kilburn. Their performance was strong, and several tracks were used on the final cut. It was the last gig Moon ever performed with the Who.[187]

The album was released on 18 August, and became their biggest and fastest seller to that date, peaking at No. 6 in the UK and No. 2 in the US.[172] Instead of touring, Daltrey, Townshend and Moon did a series of promotional television interviews, while Entwistle worked on the soundtrack for The Kids Are Alright.[188]

On 6 September, Moon attended a party held by Paul McCartney to celebrate Buddy Holly's birthday. Upon arriving back at his flat, Moon took 32 tablets of Heminevrin—a drug prescribed to combat his alcohol withdrawal.[189] He passed out the following morning, and was discovered dead later that day.[190][189]

1978–1983

The day after Moon's death, Townshend issued a statement saying "We are more determined than ever to carry on, and we want the spirit of the group to which Keith contributed so much to go on, although no human being can ever take his place."[191] In November 1978, Kenney Jones, formerly of the Small Faces and the Faces, joined the band as Moon's successor.[192] Keyboardist John "Rabbit" Bundrick also joined the live band as an unofficial member.[193] Bundrick had been scheduled to play on Who Are You, but he was unavailable due to an injury.[194]

On 2 May 1979, the Who returned to the stage with a well-received concert at the Rainbow Theatre in London, followed up over the spring and summer by performances at the Cannes Film Festival in France,[195] in Scotland, at Wembley Stadium in London, in West Germany, at the Capitol Theater in Passaic, New Jersey, and in five dates at Madison Square Garden in New York City.[196]

That year also saw the release of the Quadrophenia film. It was directed by Franc Roddam in his feature-directing début,[197] and features straightforward acting rather than musical numbers as in Tommy. Sting starred as the Ace Face, a fellow mod and friend of Jimmy. John Lydon was considered as Jimmy, but the role went to Phil Daniels.[198] The soundtrack was Jones' first appearance on record after taking over full-time from Moon after his death, performing on newly written material not on the original album.[199] The film was a critical and box office success in the UK[200] and appealed to the growing mod revival movement. The Jam were musically influenced by the Who, and critics noticed a similarity between Townshend and the group's leader, Paul Weller.[201]

The Kids Are Alright was also completed in 1979. It was a retrospective of the band's career to that date, directed by Jeff Stein.[202] The film included footage of the band at Monterey, Woodstock and Pontiac, and clips from the Smothers Brothers' show and Russell Harty Plus.[203] Moon had died during production, one week after he had seen the rough cut with Daltrey. The film contains Moon's final live performance at Shepperton Studios,[204] and an audio track of him playing over silent footage of himself was the last time he ever played the drums.[205]

In December, the Who became the third band, after the Beatles and the Band, to be featured on the cover of Time. The article, written by Jay Cocks, said the band had "outpaced, outlasted, outlived and outclassed" all of their rock band contemporaries.[206]

Cincinnati tragedy

On 3 December 1979, a crowd crush at the Who's gig at the Riverfront Coliseum, Cincinnati, Ohio killed 11 fans.[207] This was partly due to the use of festival seating, where the first to enter the venue get the best positions to view the concert. Some fans waiting outside mistook the band's sound check for the actual concert, and attempted to force their way inside. When only a few entrance doors were opened, a bottleneck situation ensued and, with so many thousands trying to gain entry, the crush became deadly.[208]

The Who were not told until after the show because civic authorities feared crowd problems if the concert were cancelled. The band were deeply shaken upon learning of the incident, and requested that appropriate safety precautions be taken at subsequent concerts.[209] The following evening, in Buffalo, New York, Daltrey told the crowd that the band had "lost a lot of family last night and this show's for them".[210]

Change and break-up

Daltrey took a short break from the Who in 1980 to work on the film McVicar, in which he took the lead role of bank robber John McVicar.[211] The soundtrack album is a Daltrey solo album featuring other members of the Who, and was his most successful solo release.[212]

The Who released two studio albums with Jones as drummer, Face Dances (1981) and It's Hard (1982). Face Dances produced a US top 20 and UK top ten hit with the single "You Better You Bet", whose video was one of the first to be shown on MTV.[213] Both Face Dances and It's Hard sold fairly well and the latter received a five-star review in Rolling Stone.[214] The single "Eminence Front" from It's Hard was a hit, and became a regular feature of live shows, including future reunions.[215]

By this time, however, Townshend had fallen into a depression, wondering if he was no longer a visionary.[216] He was again at odds with Daltrey and Entwistle, who merely wanted to tour and play hits. In addition, Jones' consistent and precise drumming was very different from Moon's wild and unpredictable playing.[217] Daltrey and Entwistle thought that Townshend had saved his best songs for his solo album, Empty Glass.[218] Townshend briefly became addicted to heroin, before cleaning up at Meg Patterson's San Diego clinic in early 1982.[219]

Townshend wanted to stop touring completely and for the Who to become solely a studio act, though Entwistle threatened to quit unless there were promises of further tours, saying "I don't intend to get off the road ... there's not much I can do about it except hope they change their minds."[220] Townshend did not change his mind, and so the Who embarked on a "farewell" tour of the US and Canada[221] with the Clash as support, including two shows at Shea Stadium in New York[222] and ending in Toronto on 17 December.[220]

Townshend spent part of 1983 trying to write material for a studio album still owed to Warner Bros. Records from a contract in 1980.[223] By the end of 1983, however, Townshend declared himself unable to generate material appropriate for the Who and paid for himself and Jones to be released from the record contract.[224] He then focused on solo albums such as White City: A Novel, The Iron Man (which featured Daltrey and Entwistle and two songs on the album credited to "the Who"), and Psychoderelict.[225]

Reunions

In July 1985, the Who re-formed for a one-off performance for Live Aid at Wembley Stadium, London.[226] The BBC transmission truck blew a fuse during the band's set, for a while interrupting the broadcast.[227] At the 1988 Brit Awards, held at the Royal Albert Hall, the band was honoured with the British Phonographic Industry's Lifetime Achievement Award.[228] They played a short set at the ceremony, which turned out to be the last time Jones played with the Who.[229]

1989 tour

In 1989, the band embarked on a 25th anniversary The Kids Are Alright reunion tour. Simon Phillips played drums, and Steve "Boltz" Bolton played lead guitar. Townshend publicly announced that he had started to suffer from tinnitus[230] and consequently relegated himself to acoustic guitar and some electric rhythm guitar to preserve his hearing.[231] Their two shows at Sullivan Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts, sold 100,000 tickets in less than eight hours (beating previous records set there by U2 and David Bowie)[232] but the tour was briefly marred after a gig in Washington DC where Townshend injured his arm onstage.[233] Some critics disliked the tour's over-produced and expanded line-up, calling it "The Who on Ice",[234] while AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine said the tour "tarnished the reputation of the Who almost irreparably".[235] The 1989 reunion tour included most of Tommy with several guest stars, including Phil Collins, Billy Idol and Elton John.[236] A 2-CD live album, Join Together, was released in 1990.[235]

Partial reunions

In 1990, the Who were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[237] The group have a featured collection in the hall's museum, including one of Moon's velvet suits, a Warwick bass used by Entwistle, and a drumhead dating from 1968.[238]

In 1991, the Who recorded a cover of Elton John's "Saturday Night's Alright for Fighting" for the tribute album Two Rooms: Celebrating the Songs of Elton John & Bernie Taupin. It was the last studio recording to feature Entwistle. In 1994, Daltrey turned 50 and celebrated with two concerts at New York's Carnegie Hall. The shows included guest spots by Entwistle and Townshend. Although all three surviving original members of the Who attended, they did not appear on stage together except for during the finale, "Join Together", with the other guests. Daltrey toured that year with Entwistle, Zak Starkey on drums and Simon Townshend filling in for his brother as guitarist.[239]

Re-formation

Revival of Quadrophenia

In 1996, Townshend, Entwistle and Daltrey performed Quadrophenia with guest stars at a concert in Hyde Park, including Starkey on drums.[240] The performance was narrated by Daniels, who had played Jimmy in the 1979 film. Despite technical difficulties the show was a success and led to a six-night residency at Madison Square Garden. This led to a US and European tour through 1996 and 1997.[240] Townshend played mostly acoustic guitar, but eventually was persuaded to play some electric.[241] In 1998, VH1 ranked the Who ninth in their list of the "100 Greatest Artists of Rock 'n' Roll".[242]

Charity shows and Entwistle's death

In late 1999, the Who performed in concert as a five-piece for the first time since 1985, with Bundrick on keyboards and Starkey on drums. The first show took place on 29 October 1999 in Las Vegas at the MGM Grand Garden Arena.[234] which was partially broadcast on TV and the internet, and later released as the DVD The Vegas Job. They then performed acoustic shows at Neil Young's Bridge School Benefit at the Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, California, on 30 and 31 October,[243] followed by gigs at the House of Blues in Chicago.[196] Finally, there were two Christmas charity shows on 22 and 23 December at the Shepherds Bush Empire in London.[244] Critics were delighted to see a rejuvenated band with a basic line-up comparable to the tours of the 1960s and 1970s. Andy Greene, writing in Rolling Stone, called the 1999 tour better than the final one with Moon in 1976.[234]

The success of 1999 led to a US tour in 2000 from June to October, moving to the UK in October and November,[196] to generally favourable reviews.[245] The final date was charity show on 27 November at the Royal Albert Hall for the Teenage Cancer trust, which included guest performances from Weller, Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder, Oasis' Noel Gallagher, Bryan Adams and Nigel Kennedy.[246] Stephen Tomas Erlewine described the Albert Hall gig as "an exceptional reunion concert".[247] The band performed the Concert for New York City at Madison Square Garden on 20 October 2001, dedicated to families of fallen New York City firemen and policemen who had lost their lives attempting to rescue people from the World Trade Center following the September 11 Attacks.[248] The Who were also honoured with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award that year.[249]

The Who played some concerts in the UK in early 2002, in preparation for a full US tour. On 27 June, the day before the first date,[250] Entwistle was found dead at the Hard Rock Hotel in Las Vegas. The cause was a heart attack in which cocaine was a contributing factor. He was 57.[251]

After Entwistle and Endless Wire

Entwistle's son, Christopher, gave a statement supporting the Who's decision to carry on. The US tour began at the Hollywood Bowl on 2 July with bassist Pino Palladino. Townshend dedicated the show to Entwistle, which ended with a montage of pictures featuring him. The tour lasted until September.[252] The loss of a founding member of the Who caused Townshend to re-evaluate his relationship with Daltrey, which had become strained several times over the band's career. He decided their friendship was important, and this ultimately led to writing and recording new material.[253]

As part of a general plan to combat bootlegging, the band began to release the Encore Series of officially released soundboard recordings via themusic.com. An official statement read "to satisfy this demand they have agreed to release their own official recordings to benefit worthy causes".[254]

In 2004, the Who released "Old Red Wine" and "Real Good Looking Boy" (with Palladino and Greg Lake, respectively, on bass), as part of a singles anthology (The Who: Then and Now), and went on an 18-date tour playing Japan, Australia, the UK and the US. Later that year, Rolling Stone ranked the Who No. 29 on their list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[255]

The Who announced in 2005 that a new album was being worked on. Townshend posted a novella called The Boy Who Heard Music on his blog, which developed into a mini-opera called Wire & Glass, forming the basis for the album.[253] Endless Wire was released on 30 October 2006. It was the first full studio album of new material since 1982's It's Hard and contained the band's first mini-opera since "Rael" on 1967's The Who Sell Out. The album reached No. 7 on Billboard and No. 9 in the UK Albums Chart.[257] Starkey was invited to join Oasis in April 2006, and the Who in November 2006, but he declined, preferring to split his time between the two.[256]

In November 2007, the documentary Amazing Journey: The Story of the Who was released. The documentary includes footage not in earlier documentaries, including film from the 1970 Leeds University appearance and the 1964 performance at the Railway Hotel when they were The High Numbers. Amazing Journey was nominated for a 2009 Grammy Award.[258]

The Who toured in support of Endless Wire, including the BBC Electric Proms at the Roundhouse in London in 2006,[259] headlining the Glastonbury Festival[260] a return appearance at the Isle of Wight.[261] and being the final act at the closing ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games.[262]

On 19 November 2012, the Who released the album Live at Hull, the band's performance in Hull on 15 February 1970—the night after the Live at Leeds gig was recorded.[263] The missing bass at the start of the gig was restored by using the recording from the Leeds gig and digitally realigning it.[264] A remastered mono mix of "My Generation" was also released as a single.[265]

Quadrophenia and More

The Who performed Quadrophenia at the Royal Albert Hall on 30 March 2010 as part of the Teenage Cancer Trust series of 10 gigs. This one-off performance of the rock opera featured guest appearances from Vedder, Kasabian's Tom Meighan and the London Symphony Orchestra's Tom Norris.[266] Townshend told Rolling Stone that the band had planned a tour for early 2010, but later stated this was jeopardised by the return of tinnitus. He experimented with a new in-ear monitoring system that was recommended by Neil Young and his audiologist.[267]

In July, Daltrey stated that they had acquired new equipment, including earpieces, that allowed Townshend to perform. The Quadrophenia and More tour was officially announced in July 2012,[268] and started on 1 November in Ottawa.[269][270] Bundrick was replaced by keyboardists Chris Stainton, Loren Gold and Frank Simes, and the latter also acted as musical director.[268] At the Valley View Casino, San Diego in February 2013, Starkey was unable to play drums after pulling a tendon and was replaced for the gig by Scott Devours who performed with less than four hours' notice.[271] The tour moved to Europe and the UK for the remainder of 2013, ending at the Wembley Arena, London, on 8 July.[272]

The Who Hits 50

In October 2013, Townshend told the London Evening Standard that the Who would stage their final tour in 2015 and will perform in locations they have never performed previously.[273][274] Daltrey later clarified that the tour is unrelated to the band's 50th anniversary—which actually occurred in 2013—and also indicated that he and Townshend were considering recording new material but would be emphasising their hits in their final stadium tour.[275] Daltrey clarified, "We can't go on touring forever ... it could be open-ended, but it will have a finality to it."[276]

Jones reunited with the Who on 14 June 2014 at a charity gig for Prostate Cancer UK his Hurtwood Polo Club, alongside Jeff Beck, Procol Harum, and Mike Rutherford.[277] Later that month, the Who announced plans for a world tour with a possible accompanying album.[275][278] The British leg of the tour is set to begin in Dublin on 26 November.[279] A new track, "Be Lucky" is scheduled to be included in a new greatest hits album to tie in with the tour.[1]

Musical style and equipment

The music of the Who can only be called rock & roll ... it is neither derivative of folk music nor the blues; the primary influence is rock & roll itself.

While the Who have been regarded primarily as a rock band, their career showed them capable of covering other styles. The original group played a mixture of trad jazz and contemporary pop hits as the Detours, which evolved into R&B during 1963.[281] The group altered their sound towards Mod the following year, particularly after hearing the Small Faces fuse Motown with a harsher R&B sound.[282][283] The group's early input was geared towards singles, though it was not straightforward pop. In 1967, Townshend coined the term "power pop" to describe the Who's style.[284] Like their contemporaries, the group were influenced by the arrival of Hendrix, particularly after the Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience met at Monterey.[74] This, combined with lengthy touring, strengthened the band's sound. In the studio, they began to develop softer pieces, particularly on Tommy onwards.[285] At the same time, they turned their attention towards albums as well as singles, creating more than mere three-minute pop songs.[286]

Daltrey's vocal style was initially based on Motown and rock and roll,[287] but from Tommy onwards, he began to tackle a wider range of material.[288] Unlike several other major rock acts, the Who have featured prominent backing vocals within the group. After "I Can't Explain" used session men to sing backing vocals, Townshend and Entwistle resolved to do better themselves on subsequent releases, producing strong falsetto harmonies.[289] Daltrey, Townshend and Entwistle all sang lead on various songs, with Moon joining in for the occasional number. Who's Next featured Daltrey and Townshend sharing the lead vocal on several songs, and biographer Dave Marsh considers the contrast between Daltrey's strong, guttural vocal and Townshend's higher and more gentle voice to be one of the album's highlights.[290]

Townshend considered himself less technical than contemporary guitarists such as Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck and wanted to stand out visually instead.[291] His playing style evolved from the banjo, favouring down strokes and using a simultaneous combination of the plectrum and fingerpicking. His rhythm playing frequently used seventh chords and suspended fourths.[292] He used a number of different electric guitars throughout his career with the Who, each of which was used to suit a particular style. In the group's early career, he favoured Rickenbacker guitars as it allowed him to fret rhythm guitar chords easily, as well as moving the neck backwards and forward to create vibrato.[293] In 1968, he began using the Gibson SG Special as his main live instrument, using one for every gig until 1973. Gibson subsequently manufactured a signature Pete Townshend SG.[294] Townshend later used a number of Gibson Les Pauls, which were custom modified and numbered from 1–9, each with different tunings.[295] From 1989 onwards, he used an Eric Clapton signature Fender Stratocaster with a Fishman Power Bridge transducer, which allowed him to combine electric and acoustic guitar songs on stage.[296]

For recording Who's Next, Townshend used a 1959 Gretsch 6120 Chet Atkins hollow body guitar, a Fender Bandmaster amp and an Edwards volume pedal, all of which were a gift from Joe Walsh. He subsequently used this combination for the majority of electric guitar recordings in the studio.[297] Although known for his electric guitar work, Townshend first used an acoustic in his professional career,[6] and has regularly recorded with one. In contrast to the many guitars smashed onstage, he has stuck to a single Gibson J-200 acoustic for songwriting and studio use.[298]

The Who were early adopters of Marshall Amplification. Entwistle was the first member to get two 4×12 speaker cabinets, quickly followed by Townshend. The group used feedback as a deliberate component of the guitar sound, both live and in the studio.[291][299] In 1967, Townshend switched to using Sound City amplifiers, custom modified by Dave Reeves, before switching to Hiwatt amplifiers 1970.[292] The group were the first to use a 1000 watt public address system for live gigs, which led to competition from bands such as the Stones and Pink Floyd for larger systems.[300]

A distinctive part of the original band's sound was Entwistle's lead bass playing, while Townshend concentrated on rhythm and chords.[17][286] Entwistle has been credited with the first popular use of Rotosound strings in 1966, after attempting to find a sound closer to a piano.[301] His bassline on "Pinball Wizard" was described by Who biographer John Atkins as "a contribution of its own without diminishing the guitar lines",[302] while he described his part on "The Real Me" from Quadrophenia, recorded in one take, as "a bass solo with vocals".[303] Entwistle used a number of different basses during the Who's career, including a Fender "Frankenstein" assembled from five different instruments, Warwick, Alembic, Gretsch and Guild.[304]

Moon's arrival in the band further strengthened this reversal of traditional rock instrumentation, as he frequently played lead parts on his drum kit.[305] His style was at odds with his contemporaries in the British rock scene, such as The Kinks' Mick Avory and The Shadows' Brian Bennett, neither of whom considered tom-toms necessary for rock music.[306] Moon started using Premier drum kits on an exclusive basis in 1966. He generally avoided using the hi-hat, and concentrated on a mix of tom rolls and cymbals.[307] Atkins praised Moon's ability to be able to synchronise with the synthesizer backing on "Won't Get Fooled Again".[308] Jones' drumming style was in sharp contrast to Moon's, and the Who at least initially were enthusiastic about working with a complete different drumming framework,[231] though Townshend later admitted "we've never really been able to replace Keith."[240] Starkey had been taught to play drums by Moon, and has been praised for his playing style which echoes Moon's without simply being a copy.[240]

In the early 1970s, the band's sound developed to include synthesizers, particularly on Who's Next and Quadrophenia,[309] and augmenting the group's live sound with backing tapes.[308] Although groups had used synthesizers before, the Who were one of the first groups to carefully integrate its sound into a basic rock structure.[310] By By Numbers the group's style had scaled back to more standard rock,[311] but synthesisers regained prominence on Face Dances.[312]

Legacy and influence

"Pete Townshend influenced Paul Weller, who, in turn influenced me."

The Who are one of the most influential rock bands of the 20th century.[1][314] Their appearances at Monterey and Woodstock helped give them a reputation as one of the greatest live rock acts[315] and they have been credited with originating the "rock opera" with Tommy.[314] Their contributions to rock iconography include the power chord,[316] windmill strum,[317] the Marshall Stack[318] and the guitar smash.[319] The band had an impact on fashion from their earliest days with their embrace of pop art[320] and their use of the Union Jack for clothing.[321] Townshend once said, "We don't change offstage. We live pop art."[322]

The Beatles were fans of the Who and appreciated their live sound when on tour.[323] Paul McCartney was inspired to write Helter Skelter in the "heavy" style of the Who,[324] while John Lennon borrowed the acoustic guitar style in "Pinball Wizard" for Polythene Pam.[325]

The Who have been called "The Godfathers of Punk"[326] with several proto punk and punk rock bands citing them as an influence, including the Sex Pistols,[182] The Clash,[327] the MC5,[328] The Stooges,[329] the Ramones[330] and Green Day.[331] In turn, the Who inspired mod revival bands particularly the Jam,[332] which helped other groups directly influenced by the Who become popular.[315] In the mid-1990s, Britpop bands such as Blur[333] and Oasis were influenced by the Who.[334]

Due to their impact on rock music, the Who have spawned a number of tribute bands. Daltrey has endorsed the Whodlums, which regularly raises money for the Teenage Cancer Trust.[335][336] Several notable bands have covered Who songs, most successfully Elton John's version of "Pinball Wizard" which reached No. 7 in the UK.[337]

Media

All three versions of the American forensic drama CSI (CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, CSI: Miami, and CSI: NY) feature songs written and performed by the Who as theme songs, "Who Are You", "Won't Get Fooled Again" and "Baba O'Riley" respectively.[338] A fourth version of the drama CSI has been announced for the 2014–15 television season entitled CSI: Cyber, using "I Can See for Miles".[339] The group's songs have featured in other popular TV series such as The Simpsons,[340] and Top Gear (which featured an episode where the presenters were tasked with being roadies for the band).[341]

Rock-orientated films such as Almost Famous,[342] School of Rock[343] and Tenacious D and the Pick of Destiny refer to the band and feature their songs,[344] and other films have used the band's material in their soundtracks, including Apollo 13 (which used "I Can See For Miles")[345] and Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (which used a take of "My Generation" recorded for the BBC).[346] Several of the band's tracks have appeared in Rock Band and its sequels.[347]

Awards and nominations

The Who have received numerous awards and accolades from the music industry, both for their recorded output and their influence. They received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the British Phonographic Industry in 1988,[348] and from the Grammy Foundation in 2001, for creative contributions of outstanding artistic significance to the field of recording.[249]

The group were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990 where their display describes them as "prime contenders, in the minds of many, for the title of World's Greatest Rock Band",[349][350] and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005.[351] Seven of the groups' albums have appeared on Rolling Stone's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, more than any other act with the exceptions of the Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones and Bruce Springsteen.[352]

Band members

- Current members

- Roger Daltrey – vocals, guitar, harmonica, percussion (1964–present)

- Pete Townshend – guitar, keyboards, vocals (1964–present)

- Past members

- John Entwistle – bass guitar, horns, keyboards, vocals (1964–2002)

- Doug Sandom – drums (1964)

- Keith Moon – drums, vocals (1964–1978)

- Kenney Jones – drums (1978–1988)

- Touring musicians

- Zak Starkey – drums, percussion (1994–present)

- Simon Townshend – guitar, backing vocals (1996–1997, 2002–present)

- Pino Palladino – bass guitar (2002–present)

- John Corey – keyboards, backing vocals (2012–present)

- Loren Gold – keyboards, backing vocals (2012–present)

- J. Greg Miller – horns (2012–present)

- Reggie Grisham – horns (2012–present)

- Frank Simes – keyboards, backing vocals, musical director (2012–present)

- Former touring musicians

- John Bundrick – keyboards, backing vocals (1979–1981, 1985–2012)

- Tim Gorman – keyboards, backing vocals (1982)

- Simon Philips – drums (1989–1991)

- Steve "Boltz" Bolton - electric guitar (1989)

Discography

- My Generation (1965)

- A Quick One (1966)

- The Who Sell Out (1967)

- Tommy (1969)

- Who's Next (1971)

- Quadrophenia (1973)

- The Who by Numbers (1975)

- Who Are You (1978)

- Face Dances (1981)

- It's Hard (1982)

- Endless Wire (2006)

- TBA (Summer 2015)

Tours and performances

- 2000 Tour

- 2001 The Concert for New York City appearance

- 2002 Tour

- 2004 Tour

- 2005 Live 8 appearance

- 2006–2007 Tour

- 2008–2009 Tour

- 2010 performances

- 2011 performances

- 2012–13 Tour

- 2012 12–12–12: The Concert for Sandy Relief appearance

- 2014–15 Tour (The Who Hits 50! Tour)

See also

References

- ^ a b c "The Who unveil first new song in eight years". BBC. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 13, 19, 24.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Neill & Kent 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 29.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Neill & Kent 2009, p. 22.

- ^ a b Marsh 1983, p. 14.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 31.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 21.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 65.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 66.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 68.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 70.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 29.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 80.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 73.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b c Eder, Bruce. "The Who – biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Icons of Rock. ABC-CLIO. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-3133-3845-8.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 91–92.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 60.

- ^ a b Kurutz, Steve. "Kit Lambert – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 55.

- ^ The Railway burned down in 2002,Christian Duffin: "Fire destroys the home of rock legends", and later became blocks of flats named after members of the band."Pastscape – Detailed Result: THE RAILWAY HOTEL". pastscape.org.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 56.

- ^ "'Who I Am': Rock icon Pete Townshend tells his story". MSNBC. Retrieved 23 November 2012

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 125.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 126.

- ^ Vedder, Eddie (15 April 2004). "The Greatest Artists of All Time: The Who". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ "50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock 'n' Roll". Rolling Stone. 24 June 2004. Archived from the original on 1 January 2009.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 134.

- ^ Howard 2004, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 152.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 100.

- ^ Carr, Roy (1979). The Kids are Alright (soundtrack) (Media notes). Polydor.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 419.

- ^ Howard 2004, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 121.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 126.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 93.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 130–132.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 182.

- ^ a b c Charlesworth, Chris (1995). Live At Leeds (1995 CD reissue) (CD). The Who. UK: Polydor. 527-169-2.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "My Generation – review". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 199.

- ^ Howard 2004, p. 108.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 203.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 217.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 109.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 218.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 225.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 227.

- ^ Unterberger, Ritchie. "A Quick One (Happy Jack)". AllMusic. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 229.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 420.

- ^ Marsh 1983.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 243.

- ^ a b Marsh 1983, p. 247.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 188.

- ^ McMichael & Lyons 1998, p. 223.

- ^ a b c Fletcher 1998, p. 189.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 193.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 194.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 197.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 266.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 273.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 149.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 275.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 250.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 196.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 293.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 190.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 191.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 294.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 317.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Wenner, Jann (28 September 1968). "The Rolling Stone Interview: Pete Townshend".

{{cite journal}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Marsh 1983, p. 320.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 316.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 221.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 318.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 324.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 220.

- ^ a b c Marsh 1983, p. 344.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 222.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 326.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 223.

- ^ a b The Who. Sanctuary Group, Artist Management. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ "The Who Kennedy Center Honors". The Kennedy Center. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 240.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 237.

- ^ a b c Evans & Kingsbury 2009, p. 165.

- ^ Spitz, Bob (1979). Barefoot in Babylon: The Creation of the Woodstock Music Festival. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 462. ISBN 0-393-30644-5.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 224.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 241.

- ^ "The Who Cement Their Place in Rock History". Rolling Stone. 25 June 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 238.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 350.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 240.

- ^ "Shake, rattle and roll!: The best live albums of all time". The Independent. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Live at Leeds: Who's best ..." The Independent. 7 June 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ "Hope I don't have a heart attack". The Telegraph. 22 June 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ "Live at Leeds". Rolling Stone. 1 November 2003. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ^ "The Who: Live at Leeds". BBC. 18 August 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 426.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 352.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, pp. 247, 421.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 354.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 364.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 283.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 373.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 375.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 378.

- ^ a b Townshend, Pete (1995) [1971]. Who's Next (CD liner). The Who. MCA Records. pp. 3–7. MCAD-11269.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 294.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 275.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 288.

- ^ Who's Next (Media notes). The Who. Track Records. 1971. 2408 102.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 421.

- ^ Smith, Larry (1999). Pete Townshend: the minstrel's dilemma. Praeger Frederick A. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-275-96472-6.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2006). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. Billboard Books

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 277.

- ^ "New Rainbow/Astoria". The Theatres Trust. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 278.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 295.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 301.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 307.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 302.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 302.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 390-91.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 406.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 401.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 412–413.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 341,344.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 412.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 414.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 428.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, pp. 335–336.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 359.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 336.

- ^ a b Perrone, Pierre (24 January 2008). "The worst gigs of all time". The Independent. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 337.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 363.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 437.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 439.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 441.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 357.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 369.

- ^ Corey, Melinda, ed. (2002). The American Film Institute desk reference. DK. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7894-8934-0.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 451.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 373.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 430.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 351.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 354.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 446.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 364.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 365.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 443.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 473.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 465.