Human papillomavirus infection: Difference between revisions

Removed sections about Novirin and Gene-Eden-VIR from treatment. They have been sanctioned by the FDA previously for false advertising and unsafe products, and appear to have placed the information as advertising. FDA link: www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementAc Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

m Reverted edits by 66.76.9.158 (talk): Unexplained removal of content (HG) (3.1.14) |

||

| Line 415: | Line 415: | ||

The [[DRACO (antiviral)]] drug is currently in the early stages of research, and may offer a generic HPV treatment if it proves successful. |

The [[DRACO (antiviral)]] drug is currently in the early stages of research, and may offer a generic HPV treatment if it proves successful. |

||

Novirin and Gene- Eden- VIR are natural antiviral supplements backed by clinical studies followed by FDA guidelines.<ref>[http://file.scirp.org/Html/36101.html Polansky, Hanan, and Edan Itzkovitz. "Gene-Eden-VIR Is Antiviral: Results of a Post Marketing Clinical Study." Pharmacology & Pharmacy 4.06 (2013): 1.]</ref><ref>[http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/02841860903440296 Polansky, Hanan, and Ido Dafni. "Gene-Eden, a broad range, natural antiviral supplement, may shrink tumors and strengthen the immune system." Acta Oncologica 49.3 (2010): 397-399.]</ref> They are designed to help the immune system target the latent form of HPV. |

|||

Alferon N, a drug against genital warts, is set to go back on the market in late 2015. It is used to treat genital warts that occur on the outside of the body and is for use only in people who are at least 18 years old.<ref>[http://www.drugs.com/mtm/alferon-n.html Alferon N- Drugs.com]</ref> |

Alferon N, a drug against genital warts, is set to go back on the market in late 2015. It is used to treat genital warts that occur on the outside of the body and is for use only in people who are at least 18 years old.<ref>[http://www.drugs.com/mtm/alferon-n.html Alferon N- Drugs.com]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 07:05, 2 November 2015

| Human papillomavirus infection | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a DNA virus from the papillomavirus family that is capable of infecting humans. Like all papillomaviruses, HPVs establish productive infections only in keratinocytes of the skin or mucous membranes. Most HPV infections are subclinical and will cause no physical symptoms; however, in some people subclinical infections will become clinical and may cause benign papillomas (such as warts [verrucae] or squamous cell papilloma), premalignant lesions that will drive to cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, oropharynx and anus.[1][2] In particular, HPV16 and HPV18 are known to cause around 70% of cervical cancer cases.[3]

Researchers have identified over 170 types of HPV, more than 40 of which are typically transmitted through sexual contact and infect the anogenital region (anus and genitals).[4] HPV types 6 and 11 are the etiological cause of genital warts.[2] Persistent infection with "high-risk" HPV types—different from the ones that cause skin warts—may progress to precancerous lesions and invasive cancer.[5] High-risk HPV infection is a cause of nearly all cases of cervical cancer.[6] However, most infections do not cause disease. New vaccines have been developed to protect against certain types of HPV infection (see HPV vaccines).

70% of clinical HPV infections in healthy young adults may regress to subclinical in one year and 90% in two years.[7] However, when the subclinical infection persists—in 5% to 10% of infected women—there is high risk of developing precancerous lesions of the vulva and cervix which can progress to invasive cancer. Progression from subclinical to clinical infection may take years, providing opportunities for detection and treatment of pre-cancerous lesions.

In more developed countries, cervical screening using a Papanicolaou (Pap) test or liquid-based cytology is used to detect abnormal cells that may develop into cancer. If abnormal cells are found, women are encouraged to have a colposcopy. During a colposcopic inspection, biopsies can be taken and abnormal areas can be removed with a simple procedure, typically with a cauterizing loop or, more commonly in the developing world—by freezing (cryotherapy). Treating abnormal cells in this way can prevent them from developing into cervical cancer. Pap smears have significantly reduced the incidence and fatalities of cervical cancer in the developed world.[8] It was estimated in 2012 that there were 528,000 cases of cervical cancer world-wide, and 266,000 deaths.[9] It is estimated that there will be 12,900 diagnosed cases of cervical cancer and 4,100 deaths in the U.S. in 2015.[8] There are about 48,000 cases of genital warts in UK men each year.[10] HPV causes cancers of the throat, anus and penis as well as causing genital warts.[11][12]

Signs and symptoms

Over 170 HPV types have been identified[14] and are referred to by number.[15][16] Types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82 are carcinogenic[17] "high-risk" sexually transmitted HPVs and may lead to the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), and/or anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN).

| Disease | HPV type |

|---|---|

| Common warts | 2, 7, 22 |

| Plantar warts | 1, 2, 4, 63 |

| Flat warts | 3, 10, 8 |

| Anogenital warts | 6, 11, 42, 44 and others[18] |

| Anal dysplasia (lesions) | 6, 16, 18, 31, 53, 58[19] |

| Genital cancers | |

| Epidermodysplasia verruciformis | more than 15 types |

| Focal epithelial hyperplasia (oral) | 13, 32 |

| Oral papillomas | 6, 7, 11, 16, 32 |

| Oropharyngeal cancer | 16 |

| Verrucous cyst | 60 |

| Laryngeal papillomatosis | 6, 11 |

Cancer

In August 2012, the Medscape website released a slides presentation about HPV and cancer risk. The following table shows the incidence of HPV associated cancers in the period of 2004-2008 in the US.[22]

| Cancer area | Average Annual Number of cases | HPV Attributable (Estimated) | HPV 16/18 Attributable (Estimated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervix | 11,967 | 11,500 | 9,100 |

| Vulva | 3,136 | 1,600 | 1,400 |

| Vagina | 729 | 500 | 400 |

| Penis | 1,046 | 400 | 300 |

| Anus (woman) | 3,089 | 2,900 | 2,700 |

| Anus (men) | 1,678 | 1,600 | 1,500 |

| Oropharynx (woman) | 2,370 | 1,500 | 1,400 |

| Oropharynx (men) | 9,356 | 5,900 | 5,600 |

| Total (women) | 21,291 | 18,000 | 15,000 |

| Total (men) | 12,080 | 7,900 | 7,600 |

An estimated 561,200 new cancer cases worldwide (5.2% of all new cancers) were attributable to HPV in 2002, making HPV one of the most important infectious causes of cancer.[21] HPV-associated cancers make up over 5% of total diagnosed cancer-cases worldwide, and this incidence is higher in developing countries where it is estimated to cause almost half a million cases each year.[21] High-risk oncogenic HPV types (including HPV 16 and HPV 18) are associated with 99.7% of all cervical cancers and an increasing number of head and neck cancers.[23][24]

About a dozen HPV types (including types 16, 18, 31, and 45) are called "high-risk" types because persistent infection may lead to cancers within stratified epithelial tissues such as cervical cancer, anal cancer, vulvar cancer, vaginal cancer, and penile cancer[21] Several types of HPV, in particular type 16, have been found to be associated with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer (OSCC), a form of head and neck cancer.[25][26] HPV-induced cancers arise when viral sequences are accidentally integrated into the cellular DNA of host cells. Some of the HPV "early" genes, such as E6 and E7, act as oncogenes that promote tumor growth and malignant transformation. Furthermore, HPV can induce a tumorigenic process through integration into a host genome which is associated with alterations in DNA copy number.[27] Oral infection with HPV increased the risk of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer independent of tobacco and alcohol use.[26] In the United States, HPV is expected to replace tobacco as the main causative agent for oral cancer, and the number of newly diagnosed HPV-associated head and neck cancers is expected to surpass that of cervical cancer cases by the year 2020.[28][29]

The p53 protein prevents cell growth and stimulates apoptosis in the presence of DNA damage. The p53 also upregulates the p21 protein, which blocks the formation of the Cyclin D/Cdk4 complex, thereby preventing the phosphorylation of RB and, in turn, halting cell cycle progression by preventing the activation of E2F. In short, p53 is a tumor suppressor gene that arrests the cell cycle when there is DNA damage.

E6 has a close relationship with the cellular protein E6-AP (E6-associated protein). E6-AP is involved in the ubiquitin ligase pathway, a system that acts to degrade proteins. E6-AP binds ubiquitin to the p53 protein, thereby flagging it for proteosomal degradation.

Most HPV infections are cleared rapidly by the immune system and do not progress to cervical cancer (see Clearance subsection in Virology). Because the process of transforming normal cervical cells into cancerous ones is slow, cancer occurs in people having been infected with HPV for a long time, usually over a decade or more (persistent infection).[30][31]

Sexually transmitted HPVs also cause a major fraction of anal cancers and approximately 25% of cancers of the mouth and upper throat (the oropharynx) (see figure).[21] The latter commonly present in the tonsil area, and HPV is linked to the increase in oral cancers in non-smokers.[32][33] Engaging in anal sex or oral sex with an HPV-infected partner may increase the risk of developing these types of cancers.[25]

Studies show a link between HPV infection and penile and anal cancer,[21] and the risk for anal cancer is 17 to 31 times higher among gay and bisexual men than among heterosexual men.[34][35] It has been suggested that anal Pap smear screening for anal cancer might benefit some sub-populations of men or women engaging in anal sex.[36] There is no consensus that such screening is beneficial, or who should get an anal Pap smear.[37][38]

Further studies have also shown a link between a wide range of HPV types and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. In vitro studies suggest that the E6 protein of the HPV types implicated may inhibit apoptosis induced by ultraviolet light.[39]

The mutational profile of HPV+ and HPV- head and neck cancer has been reported, further demonstrating that they are fundamentally distinct diseases.[40]

Skin warts

All HPV infections can cause warts (verrucae), which are noncancerous skin growths. Infection with these types of HPV causes a rapid growth of cells on the outer layer of the skin.[41] In a study, HPV types 2, 27 and 57 were most frequently observed with warts, while HPV 1, 2, 63, 27 were commonly observed on clinically normal skin.[42] Types of warts include:

- Common warts: Some "cutaneous" HPV types cause common skin warts. Common warts are often found on the hands and feet, but can also occur in other areas, such as the elbows or knees. Common warts have a characteristic cauliflower-like surface and are typically slightly raised above the surrounding skin. Cutaneous HPV types can cause genital warts but are not associated with the development of cancer.

- Plantar warts are found on the soles of the feet. Plantar warts grow inward, generally causing pain when walking.

- Subungual or periungual warts form under the fingernail (subungual), around the fingernail or on the cuticle (periungual). They may be more difficult to treat than warts in other locations.[43]

- Flat warts: Flat warts are most commonly found on the arms, face or forehead. Like common warts, flat warts occur most frequently in children and teens. In people with normal immune function, flat warts are not associated with the development of cancer.[44]

Genital warts are quite contagious, while common, flat, and plantar warts are much less likely to spread from person to person.

Genital warts

Genital or anal warts (condylomata acuminata or venereal warts) are the most easily recognized sign of genital HPV infection. Although a wide variety of HPV types can cause genital warts, types 6 and 11 account for about 90% of all cases.[45][46]

Most people who acquire genital wart-associated HPV types clear the infection rapidly without ever developing warts or any other symptoms. People may transmit the virus to others even if they do not display overt symptoms of infection.

HPV types that tend to cause genital warts are not those that cause cervical cancer.[47] Since an individual can be infected with multiple types of HPV, the presence of warts does not rule out the possibility of high-risk types of the virus also being present.

The types of HPV that cause genital warts are usually different from the types that cause warts on other parts of the body, such as the hands or inner thighs.

Respiratory papillomatosis

HPV types 6 and 11 can cause a rare condition known as recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, in which warts form on the larynx[48] or other areas of the respiratory tract.[31][49]

These warts can recur frequently, may require repetitive surgery, may interfere with breathing, and in extremely rare cases can progress to cancer.[31][50]

Immunocompromised

In very rare cases, HPV may cause epidermodysplasia verruciformis in immunocompromised individuals. The virus, unchecked by the immune system, causes the overproduction of keratin by skin cells, resulting in lesions resembling warts or cutaneous horns.[51]

For instance, Dede Koswara, an Indonesian man developed warts that spread across his body and became root-like growths. Attempted treatment by both Indonesian and American doctors included surgical removal of the warts.

Transmission

Perinatal

Although genital HPV types can be transmitted from mother to child during birth, the appearance of genital HPV-related diseases in newborns is rare. However, the lack of appearance does not rule out asymptomatic latent infection, as the virus has proven to be capable of hiding for decades. Perinatal transmission of HPV types 6 and 11 can result in the development of juvenile-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (JORRP). JORRP is very rare, with rates of about 2 cases per 100,000 children in the United States.[31] Although JORRP rates are substantially higher if a woman presents with genital warts at the time of giving birth, the risk of JORRP in such cases is still less than 1%.

Genital infections

Since cervical and female genital infection by specific HPV types is highly associated with cervical cancer, those types of HPV infection have received most of the attention from scientific studies.

HPV infections in that area are transmitted primarily via sexual activity.[52]

Of the 120 known human papillomaviruses, 51 species and three subtypes infect the genital mucosa.[53] 15 are classified as high-risk types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82), 3 as probable high-risk (26, 53, and 66), and 12 as low-risk (6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, and CP6108).[54]

If a woman has at least one different partner per year for four years, the probability that she will leave college with an HPV infection is greater than 85%.[55] Condoms do not completely protect from the virus because the areas around the genitals including the inner thigh area are not covered, thus exposing these areas to the infected person’s skin.[55]

Hands

Studies have shown HPV transmission between hands and genitals of the same person and sexual partners. Hernandez tested the genitals and dominant hand of each person in 25 couples every other month for an average of 7 months. She found 2 couples where the man's genitals infected the woman's hand with high risk HPV, 2 where her hand infected his genitals, 1 where her genitals infected his hand, 2 each where he infected his own hand, and she infected her own hand.[56][57] Hands were not the main source of transmission in these 25 couples, but they were significant.

Partridge reports men's fingertips became positive for high risk HPV at more than half the rate (26% per 2 years) as their genitals (48%).[58] Winer reports 14% of fingertip samples from sexually active women were positive.[59] None of these studies reports whether participants were asked to wash or not wash their hands before testing.

Non-sexual hand contact seems to have little or no role in HPV transmission. Winer found all 14 fingertip samples from virgin women negative at the start of her fingertip study.[59] In a separate report on genital HPV infection, 1% of virgin women (1 of 76) with no sexual contact tested positive for HPV, while 10% of virgin women reporting non-penetrative sexual contact were positive (7 of 72).[60]

Shared objects

Sharing of possibly contaminated objects may transmit HPV.[61][62][63] Although possible, transmission by routes other than sexual intercourse is less common for female genital HPV infection.[52] Fingers-genital contact is a possible way of transmission but unlikely to be a significant source.[59][64]

Blood

Though it has traditionally been assumed that HPV is not transmissible via blood—as it is thought to only infect cutaneous and mucosal tissues—recent studies have called this notion into question. Historically, HPV DNA has been detected in the blood of cervical cancer patients.[65] In 2005, a group reported that, in frozen blood samples of 57 sexually naive pediatric patients who had vertical or transfusion-acquired HIV infection, 8 (14.0%) of these samples also tested positive for HPV-16.[66] This seems to indicate that it may be possible for HPV to be transmitted via blood transfusion. However, as non-sexual transmission of HPV by other means is not uncommon, this could not be definitively proven. In 2009, a group tested Australian Red Cross blood samples from 180 healthy male donors for HPV, and subsequently found DNA of one or more strains of the virus in 15 (8.3%) of the samples.[67] However, it is important to note that detecting the presence of HPV DNA in blood is not the same as detecting the virus itself in blood, and whether or not the virus itself can or does reside in blood in infected individuals is still unknown. As such, it remains to be determined whether HPV can or cannot be transmitted via blood.[65] This is of concern, as blood donations are not currently screened for HPV, and at least some organizations such as the American Red Cross and other Red Cross societies do not presently appear to disallow HPV-positive individuals from donating blood.[68]

Surgery

Hospital transmission of HPV, especially to surgical staff, has been documented. Surgeons, including urologists and/or anyone in the room is subject to hpv infection by inhalation of noxious viral particles during electrocautery or laser ablation of a condyloma (wart).[69] There has been a case report of a laser surgeon who developed extensive laryngeal papillomatosis after providing laser ablation to patients with anogenital condylomata.[69]

Virology

| Human papillomavirus infection | |

|---|---|

| |

| TEM of papillomavirus | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group I (dsDNA)

|

| Order: | Unranked

|

| Family: | |

| Genera | |

|

Alphapapillomavirus | |

HPV infection is limited to the basal cells of stratified epithelium, the only tissue in which they replicate.[70] The virus cannot bind to live tissue; instead, it infects epithelial tissues through micro-abrasions or other epithelial trauma that exposes segments of the basement membrane.[70] The infectious process is slow, taking 12–24 hours for initiation of transcription. It is believed that involved antibodies play a major neutralizing role while the virions still reside on the basement membrane and cell surfaces.[70]

HPV lesions are thought to arise from the proliferation of infected basal keratinocytes. Infection typically occurs when basal cells in the host are exposed to infectious virus through a disturbed epithelial barrier as would occur during sexual intercourse or after minor skin abrasions. HPV infections have not been shown to be cytolytic; rather, viral particles are released as a result of degeneration of desquamating cells. HPV can survive for many months and at low temperatures without a host; therefore, an individual with plantar warts can spread the virus by walking barefoot.[46]

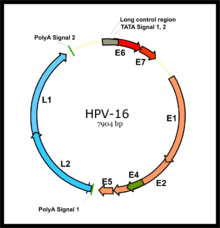

HPV is a small DNA virus with a genome of approximately 8000 base pairs.[71] The HPV life cycle strictly follows the differentiation program of the host keratinocyte. It is thought that the HPV virion infects epithelial tissues through micro-abrasions, whereby the virion associates with putative receptors such as alpha integrins and laminins, leading to entry of the virions into basal epithelial cells through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and/or caveolin-mediated endocytosis depending on the type of HPV. At this point, the viral genome is transported to the nucleus by unknown mechanisms and establishes itself at a copy number of 10-200 viral genomes per cell. A sophisticated transcriptional cascade then occurs as the host keratinocyte begins to divide and become increasingly differentiated in the upper layers of the epithelium.

The phylogeny of the various strains of HPV generally reflects the migration patterns of Homo sapiens and suggests that HPV may have diversified along with the human population. Studies suggest that HPV evolved along five major branches that reflect the ethnicity of human hosts, and diversified along with the human population.[72] Researchers have identified two major variants of HPV16, European (HPV16-E), and Non-European (HPV16-NE).[73]

E6/E7 proteins

The two primary oncoproteins of high risk HPV types are E6 and E7. The “E” designation indicates that these two proteins are expressed early in the HPV life cycle, while the "L" designation indicates late expression.[23] The HPV genome is composed of six early (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7) ORFs, two late (L1 and L2) ORFs, and a non-coding long control region (LCR).[74] After the host cell is infected viral early promoter is activated and a polycistronic primary RNA containing all six early ORFs is transcribed. This polycistronic RNA then undergoes active RNA splicing to generate multiple isoforms of mRNAs.[75] One of the spliced isoform RNAs, E6*I, serves as an E7 mRNA to translate E7 protein.[76] However, viral early transcription subjects to viral E2 regulation and high E2 levels repress the transcription. HPV genomes integrate into host genome by disruption of E2 ORF, preventing E2 repression on E6 and E7. Thus, viral genome integration into host DNA genome increases E6 and E7 expression to promote cellular proliferation and the chance of malignancy. The degree to which E6 and E7 are expressed is correlated with the type of cervical lesion that can ultimately develop.[71]

- Role in cancer

The E6/E7 proteins inactivate two tumor suppressor proteins, p53 (inactivated by E6) and pRb (inactivated by E7).[16] The viral oncogenes E6 and E7[77] are thought to modify the cell cycle so as to retain the differentiating host keratinocyte in a state that is favourable to the amplification of viral genome replication and consequent late gene expression. E6 in association with host E6-associated protein, which has ubiquitin ligase activity, acts to ubiquitinate p53, leading to its proteosomal degradation. E7 (in oncogenic HPVs) acts as the primary transforming protein. E7 competes for retinoblastoma protein (pRb) binding, freeing the transcription factor E2F to transactivate its targets, thus pushing the cell cycle forward. All HPV can induce transient proliferation, but only strains 16 and 18 can immortalize cell lines in vitro. It has also been shown that HPV 16 and 18 cannot immortalize primary rat cells alone; there needs to be activation of the ras oncogene. In the upper layers of the host epithelium, the late genes L1 and L2 are transcribed/translated and serve as structural proteins that encapsidate the amplified viral genomes. Once the genome is encapsidated, the capsid appears to undergo a redox-dependent assembly/maturation event, which is tied to a natural redox gradient that spans both suprabasal and cornified epithelial tissue layers. This assembly/maturation event stabilizes virions, and increases their specific infectivity.[78] Virions can then be sloughed off in the dead squames of the host epithelium and the viral lifecycle continues.[79] A 2010 study has found that E6 and E7 are involved in beta-catenin nuclear accumulation and activation of Wnt signaling in HPV-induced cancers.[80]

E2 research

Human papillomavirus is a DNA virus that cause skin lesions keratinocytes. There are two categories of HPVs, high and low risk. High-risk papillomaviruses are HPVs-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 55, 58, and 59, which are often found on cancer cells. HPVs that produce skin lesions are low risk HPVs, but HPV-6 and HPV-11 are associated with genital warts. The mechanism of infection of these viruses has been widely researched, particularly the oncogene protein Papillomaviridae E2/E1 and E6/E7, since they are considered the essential part for the development of cancer cells.[81]

In a recent study, 99.7% of one thousand cases of invasive cervical cancer were HPV positive to HPV16, being the most common followed by HPV-18 DNA. High Risk HPV E6 and E7 are more active than E2 in cellular transformation than low risk HPVs.[81] The oncogenes E7 and E6 have been found to change Keratinocytes by altering their cell cycle. E6 binds to P53 and degrades it preventing cell death apoptosis and promoting the replication of viral DNA. P53 is a repair mechanism that destroys any abnormal cells or arrests the cell cycle. Genetic changes in the DNA, such as, the introduction of viral DNA, which transforms and destabilizes the cell. Additional research has been performed in the apoptotic effects of papillomavirus E2. The research findings that the E2 protein in HeLa cells induce p53, causing arrest of the cell cycle and apoptosis. But, the induce p53 accumulation was not correlated to the cell growth arrest at G1 phase. This suggests that apoptosis and cell cycle arrest are independent of each other.[81][82] Researchers used biochemical and genetic approaches to test the hypothesis that apoptosis by BPVI and HPV18 E2 proteins in HeLa cells is independent of p53. One experiment demonstrated that E2 induced apoptosis was set off by Bax, one of the best-known p53 promoting genes. Corroborating the independent pathway for cellular apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.

A comparative research study was conducted to study the transcription activity of high and low risk papillomaviruse E2 protein and affinity of the E2 binding regions of high and low risk HPVs. The study used protein encoded in HPV 16, HPV18, and HPV11 and Bovine -1, along with comparative DNA binding shift assays, cell free transcription systems, cofactors, to determine the affinity the oncoprotein E2 of both types of HPVs.[81] The BPV1 has been used to model the replication of papillomaviruse. The viral gene of BPV1 gene contains several promoters that are activated by E2 protein.[83]In vivo studies of DNA using HeLa cells revealed that different types of E2 proteins showed different transcription and repression activities based on the binding sites of E2. In vivo studies also revealed the high transcriptional activity of high risk HPV-16 E2, which suggests that HPV-16 has a very efficient E2 that regulates the E6/E7 oncoproteins that results in the control of the viral life cycle. The less efficient E6/E7 oncoproteins are expressed all lower levels in low risks HPVs. The regulation of the E6 promoter of the high risk E2 protein of the HPVs can lead to the development of cancer due to the viral integration.[81][82]

Latency period

Once an HPV virion invades a cell, an active infection occurs, and the virus can be transmitted. Several months to years may elapse before squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL) develop and can be clinically detected. The time from active infection to clinically detectable disease may make it difficult for epidemiologists to establish which partner was the source of infection.[84]

Clearance

Most HPV infections are cleared up by most people without medical action or consequences. The table provides data for high-risk types (i.e. the types found in cancers).

| Months after Initial Positive Test | 8 Months | 12 Months | 18 Months |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of Men Tested Negative[85] | 70% | 80% | 100% |

Clearing an infection does not always create immunity if there is a new or continuing source of infection. Hernandez' 2005-6 study of 25 couples reports "A number of instances indicated apparent reinfection [from partner] after viral clearance."[56]

Prevention

HPV infection is the most frequently sexually transmitted disease in the world.[86] Methods of reducing the chances of infection include sexual abstinence, condoms, vaccination and microbicides.

Vaccines

Two vaccines are available to prevent infection by some HPV types: Gardasil, marketed by Merck, and Cervarix, marketed by GlaxoSmithKline. Both protect against initial infection with HPV types 16 and 18, which cause most of the HPV associated cancer cases. Gardasil also protects against HPV types 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts. Gardasil is a recombinant quadrivalent vaccine, whereas Cervarix is bivalent, and is prepared from virus-like particles (VLP) of the L1 capsid protein.

The vaccines provide little benefit to women having already been infected with HPV types 16 and 18.[87] For this reason, the vaccine is recommended primarily for those women not yet having been exposed to HPV during sex. The World Health Organization position paper on HPV vaccination clearly outlines appropriate, cost-effective strategies for using HPV vaccine in public sector programs.[88][needs update]

Both vaccines are delivered in three shots over six months. In most countries, they are funded only for female use, but are approved for male use in many countries, and funded for teenage boys in Australia. The vaccine does not have any therapeutic effect on existing HPV infections or cervical lesions.[89] In 2010, 49% of teenage girls in the US got the HPV vaccine.

Following studies suggesting that the vaccine is more effective in younger girls[90] than in older teenagers, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Mexico, the Netherlands and Quebec began offering the vaccine in a two-dose schedule for girls aged under 15 in 2014.

It remains a recommendation that women continue cervical screening, such as Pap smear testing, even after receiving the vaccine. Cervical cancer screening recommendations have not changed for females who receive HPV vaccine.[89][needs update] Without continued screening, the number of cervical cancers preventable by vaccination alone is less than the number of cervical cancers prevented by regular screening alone.[91][92]

Both men and women are carriers of HPV.[93] The Gardasil vaccine also protects men against anal cancers and warts and genital warts.[94]

Duration of both vaccines' efficacy has been observed since they were first developed, and is expected to be longlasting.[95]

In December 2014, the FDA approved a nine-valent Gardasil-based vaccine, Gardasil 9, to protect against infection with the four strains of HPV covered by the first generation of Gardasil as well as five other strains responsible for 20% of cervical cancers (HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52, and HPV-58).[96]

Condoms

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that male "condom use may reduce the risk for genital human papillomavirus (HPV) infection" but provides a lesser degree of protection compared with other sexual transmitted diseases "because HPV also may be transmitted by exposure to areas (e.g., infected skin or mucosal surfaces) that are not covered or protected by the condom."[97]

Female condoms provide somewhat greater protection than male condoms, as the female condom allows for less skin contact.[98]

Studies have suggested that regular condom use can effectively limit the ongoing persistence and spread of HPV to additional genital sites in individuals already infected.[needs update]

Disinfection

The virus is relatively hardy and immune to many common disinfectants. Exposure to 90% ethanol for at least 1 minute, 2% glutaraldehyde, 30% Savlon, and/or 1% sodium hypochlorite can disinfect the pathogen.[99]

The virus is resistant to drying and heat, but killed by 100 °C (212 °F) and ultraviolet radiation.[99]

Diagnosis

There are multiple types of HPV, sometimes called "low risk" and "high risk" types. Low risk types cause warts and high risk types can cause lesions or cancer.[5]

Health guidelines recommend HPV testing in patients with specific indications including certain abnormal Pap test results.[needs update]

Cervical testing

According to the National Cancer Institute, “The most common test detects DNA from several high-risk HPV types, but it cannot identify the type(s) that are present. Another test is specific for DNA from HPV types 16 and 18, the two types that cause most HPV-associated cancers. A third test can detect DNA from several high-risk HPV types and can indicate whether HPV-16 or HPV-18 is present. A fourth test detects RNA from the most common high-risk HPV types. These tests can detect HPV infections before cell abnormalities are evident.

“Theoretically, the HPV DNA and RNA tests could be used to identify HPV infections in cells taken from any part of the body. However, the tests are approved by the FDA for only two indications: for follow-up testing of women who seem to have abnormal Pap test results and for cervical cancer screening in combination with a Pap test among women over age 30.” [100]

In April 2011, the Food and Drug Administration approved the cobas HPV Test, manufactured by Roche.[101] This cervical cancer screening test “specifically identifies types HPV 16 and HPV 18 while concurrently detecting the rest of the high risk types (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68).”[101]

The cobas HPV Test was evaluated in the ATHENA trial, which studied more than 47,000 U.S. women 21 years old and older undergoing routine cervical cancer screening.[102] Results from the ATHENA trial demonstrated that 1 in 10 women, age 30 and older, who tested positive for HPV 16 and/or 18, actually had cervical pre-cancer even though they showed normal results with the Pap test.[102]

In March 2003, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the Hybrid Capture 2 test manufactured by Qiagen/Digene,[103] which is a "hybrid-capture" test[104][105] as an adjunct to Pap testing. The test may be performed during a routine Pap smear. It detects the DNA of 13 "high-risk" HPV types that most commonly affect the cervix, it does not determine the specific HPV types. Hybrid Capture 2 is the most widely studied commercially available HPV assay and the majority of the evidence for HPV primary testing in population based screening programmes is based on the Hybrid Capture 2 assay.[106]

The recent outcomes in the identification of molecular pathways involved in cervical cancer provide helpful information about novel bio- or oncogenic markers that allow monitoring of these essential molecular events in cytological smears, histological, or cytological specimens. These bio- or onco- markers are likely to improve the detection of lesions that have a high risk of progression in both primary screening and triage settings. E6 and E7 mRNA detection PreTect HPV-Proofer, (HPV OncoTect) or p16 cell-cycle protein levels are examples of these new molecular markers. According to published results, these markers, which are highly sensitive and specific, allow to identify cells going through malignant transformation.[107][108]

In October 2011 the US Food and Drug Administration approved the Aptima HPV Assay test for RNA created when and if any HPV strains start creating cancers (see virology).[109][110][111]

The vulva/vagina has been sampled with Dacron swabs and shows more HPV than the cervix. Among women who were HPV positive in either place, 90% were positive in the vulvovaginal region, 46% in the cervix.[60]

Oral testing

Studies have found heightened HPV in mouth cell samples from people with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Studies have not found significant HPV in mouth cells after sampling with toothbrushes (5 of 2,619 samples)[60] and cytobrushes (no oral transmission found).[56]

Testing men

Research studies have tested for and found HPV, including high-risk types (i.e. the types found in cancers), on fingers, mouth, saliva, anus, urethra, urine, semen, blood, scrotum and penis. However, most research tests have used Dacron swabs and custom analysis not available to the general public.[112][needs update]

A Brazilian study used the readily available Qiagen/Digene test mentioned above (off label) to test men's penis, scrotum and anus.[113] Each of the 50 men had been a partner for at least 6 months of a woman who was positive for high risk HPV. They found high risk HPV on 60% of these men, primarily the penis. "The specimens were obtained using a vigorous motion of the conical brush included in the Digene kit" "after spraying the anogenital region with saline solution."[113][needs update]

A slightly different method also used cytobrushes (but custom lab analysis) and found 37% of 582 Mexican army recruits positive for high risk HPV.[114][needs update] They were told not to wash genitals for 12 hours before sampling. (Other studies are silent on washing, a particular gap in studies of hands). They included the urethra as well as scrotum and penis, but the urethra added less than 1% to the HPV rate. Studies like this led Giuliano to recommend sampling the glans, shaft and crease between them and scrotum, since sampling the urethra or anus added very little to diagnosis.[58] Dunne recommends glans, shaft, their crease, and foreskin.[112]

A small study of cytobrushes on 10 US men where the brush was wet, rather than the skin, found 2 of 10 men were positive for HPV (type not reported).[115][needs update] Their lab analysis was not the same as either study above. This small study found 4 of 10 men positive for HPV when skin was rubbed with 600 grit emery paper, then swabbed with a wet Dacron swab. Since emery paper and brush were analyzed together at the lab, it is not known if the emery paper collected viruses or loosened them for the swab to collect.

Studies have found collection by men from their own skin (with emery paper and Dacron swabs) as effective as by a clinician, sometimes more so, since patients were more willing to scrape vigorously.[116][needs update][117][118][needs update]

Other studies have used similar cytobrushes to sample fingertips and under the fingernails, though without wetting the area or brush.[59][64][119][needs update]

Other studies analyzed urine, semen and blood and found varying amounts of HPV,[112] but there is no publicly available test for them.

There is not a wide range of tests even though HPV is common. Clinicians depend on the vaccine among young people and high clearance rates (see Clearance subsection in Virology) to create a low risk of disease and mortality, and treat the cancers when they appear. Others believe that reducing HPV infection in more men and women, even when it has no symptoms, is important (herd immunity) to prevent more cancers rather than just treating them.[120][121][needs update] Where tests are used, negative test results show safety from transmission, and positive test results show where shielding (condoms, gloves) is needed to prevent transmission until the infection clears.[122]

Other testing

Although it is possible to test for HPV DNA in other kinds of infections,[123] there are no FDA-approved tests for general screening in the United States[34] or tests approved by the Canadian government,[124] since the testing is inconclusive and considered medically unnecessary.[125]

Genital warts are the only visible sign of low-risk genital HPV, and can be identified with a visual check. These visible growths, however, are the result of non-carcinogenic HPV types. Five percent acetic acid (vinegar) is used to identify both warts and squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (SIL) lesions with limited success[citation needed] by causing abnormal tissue to appear white, but most doctors have found this technique helpful only in moist areas, such as the female genital tract.[citation needed] At this time, HPV test for males are used only in research.[citation needed]

Research into testing for HPV by antibody presence has been done. The approach is looking for an immune response in blood, which would contain antibodies for HPV if the patient is HPV positive.[126][127][128][129] The reliability of such tests hasn't been proven, as there hasn't been a FDA approved product as of March 2014; testing by blood would be a less invasive test for screening purposes.

Treatment

There is currently no specific treatment for HPV infection.[47][130][131] However, the viral infection, more often than not, clears to undetectable levels by itself.[132] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the body’s immune system clears HPV naturally within two years for 90% of cases (see Clearance subsection in Virology for more detail).[47] However, experts do not agree on whether the virus is completely eliminated or reduced to undetectable levels, and it is difficult to know when it is contagious.[133]

The DRACO (antiviral) drug is currently in the early stages of research, and may offer a generic HPV treatment if it proves successful. Novirin and Gene- Eden- VIR are natural antiviral supplements backed by clinical studies followed by FDA guidelines.[134][135] They are designed to help the immune system target the latent form of HPV.

Alferon N, a drug against genital warts, is set to go back on the market in late 2015. It is used to treat genital warts that occur on the outside of the body and is for use only in people who are at least 18 years old.[136]

A 2014 study indicates that lopinavir is effective against the human papilloma virus (HPV). The study used the equivalent of one tablet twice a day applied topically to the cervices of women with high-grade and low-grade precancerous conditions. After three months of treatment, 82.6% of the women who had high-grade disease had normal cervical conditions, confirmed by smears and biopsies.[137]

Follow up care is usually recommended and practiced by many health clinics.[138] Follow-up is sometimes not successful because a portion of those treated do not return to be evaluated. In addition to the normal methods of phone calls and mail, text messaging and email can improve the number of people who return for care.[139]

Epidemiology

Cutaneous HPVs

Infection with cutaneous HPVs is ubiquitous.[140] Some HPV types, such as HPV-5, may establish infections that persist for the lifetime of the individual without ever manifesting any clinical symptoms. Other cutaneous HPVs, such as HPV types 1 or 2, may cause common warts in some infected individuals.[citation needed] Skin warts are most common in childhood and typically appear and regress spontaneously over the course of weeks to months. About 10% of adults also suffer from recurring skin warts.[citation needed] All HPVs are believed to be capable of establishing long-term "latent" infections in small numbers of stem cells present in the skin. Although these latent infections may never be fully eradicated, immunological control is thought to block the appearance of symptoms such as warts. Immunological control is HPV type-specific, meaning that an individual may become resistant to one HPV type while remaining susceptible to other types.

Lung cancer

There has been evidence linking HPV to benign and malignant tumors of the upper respiratory tract. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has found that people with lung cancer were significantly more likely to have several high-risk forms of HPV antibodies compared to those who did not have lung cancer.[141] Researchers looking for HPV among 1,633 lung cancer patients and 2,729 people without the lung disease found that people with lung cancer had more types of HPV than non-cancer patients did, and among lung cancer patients, the chances of having eight types of serious HPV were significantly increased.[142] In addition, there has been expression of HPV structural proteins by immunohistochemistry and in vitro studies that suggests HPV presence in bronchial cancer and its precursor lesions.[143] Another study detected HPV in the EBC, bronchial brushing and neoplastic lung tissue of cases, and found a presence of an HPV infection in 16.4% of the subjects affected by non-small cell lung cancer, but in none of the controls.[144] The reported average frequencies of HPV in lung cancers were 17% and 15% in Europe and the America, respectively, and the mean number of HPV in Asian lung cancer samples was 35.7%, with a considerable heterogeneity between certain countries and regions.[145]

Throat cancer

In recent years, the United States has experienced an increase in the number of cases of throat cancer caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) Type 16. Throat cancers associated with HPV have been estimated to have increased from 0.8 cases per 100,000 people in 1988 to 2.6 per 100,000 in 2004.[146] Researchers explain this recent data by an increase in oral sex. Moreover, findings indicate this type of cancer is much more prevalent in men than in women, something that needs to be further explored.[147] Currently, two immunizations, Gardasil and Cervarix, are recommended to girls to prevent HPV related cervical cancer but not as a precaution against HPV related throat cancer.[148]

Genital HPVs

HPV of the genitals is the most common sexually transmitted infection globally.[9] Most people get infected at some point in time and about 10% of women are currently infected.[9] A large increase in the incidence of genital HPV infection occurs at the age when individuals begin to engage in sexual activity. The great majority of genital HPV infections never cause any overt symptoms and are cleared by the immune system in a matter of months. As with cutaneous HPVs, immunity is believed to be HPV type-specific. Some infected individuals may fail to bring genital HPV infection under immunological control. Lingering infection with high-risk HPV types, such as HPVs 16, 18, 31, and 45, can lead to the development of cervical cancer or other types of cancer.[149] In addition to persistent infection with high-risk HPV types, epidemiological and molecular data suggest that co-factors such as the cigarette smoke carcinogen benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) enhance development of certain HPV-induced cancers.[150][151]

High-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are together responsible for over 65% of cervical cancer cases.[152][153] Type 16 causes 41 to 54% of cervical cancers,[152][154] and accounts for an even greater majority of HPV-induced vaginal/vulvar cancers,[155] penile cancers, anal cancers and head and neck cancers.[156]

Anal cancer

Examination of squamous cell carcinoma tumor tissues from patients in Denmark and Sweden showed a high proportion of anal cancers to be positive for the types of HPV that are also associated with high risk of cervical cancer. In another study done, high-risk types of HPV, notably HPV-16, were detected in 84 percent of anal cancer specimens examined. Based on the study in Denmark and Sweden, Parkin estimated that 90% of anal cancers are attributable to HPV.

Other

Infection with HPV has also been linked with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[157]

United States of America

| Age (years) | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| 14 to 19 | 24.5% |

| 20 to 24 | 44.8% |

| 25 to 29 | 27.4% |

| 30 to 39 | 27.5% |

| 40 to 49 | 25.2% |

| 50 to 59 | 19.6% |

| 14 to 59 | 26.8% |

HPV is estimated to be the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States.[158] Most sexually active men and women will probably acquire genital HPV infection at some point in their lives.[152] The American Social Health Association reported estimates that about 75–80% of sexually active Americans will be infected with HPV at some point in their lifetime.[159][160] By the age of 50 more than 80% of American women will have contracted at least one strain of genital HPV.[158][161][162]

It was estimated that, in the year 2000, there were approximately 6.2 million new HPV infections among Americans aged 15–44; of these, an estimated 74% occurred to people between ages of 15 and 24.[163] Of the STDs studied, genital HPV was the most commonly acquired.[163] In the United States, it is estimated that 10% of the population has an active HPV infection, 4% has an infection that has caused cytological abnormalities, and an additional 1% has an infection causing genital warts.[164]

Estimates of HPV prevalence vary from 14% to more than 90%.[165] One reason for the difference is that some studies report women who currently have a detectable infection, while other studies report women who have ever had a detectable infection.[166][167] Another cause of discrepancy is the difference in strains that were tested for.

One study found that, during 2003–2004, at any given time, 26.8% of women aged 14 to 59 were infected with at least one type of HPV. This was higher than previous estimates; 15.2% were infected with one or more of the high-risk types that can cause cancer.[158][168]

The prevalence for high-risk and low-risk types is roughly similar over time.[158]

Human papillomavirus is not included among the diseases that are typically reportable to the CDC as of 2011.[169][170]

History

In 1972, the association of the human papillomaviruses with skin cancer in epidermodysplasia verruciformis was proposed by Stefania Jabłońska in Poland. In 1978, Jabłońska and Gerard Orth at the Pasteur Institute discovered HPV-5 in skin cancer.[171][page needed] In 1976 Harald zur Hausen published the hypothesis that human papilloma virus plays an important role in the cause of cervical cancer. In 1983 and 1984 zur Hausen and his collaborators identified HPV16 and HPV18 in cervical cancer.[172]

The HeLa cell line contains extra DNA in its genome that originated from HPV type 18.[173]

References

- ^ Stanley, Margaret A; Winder, David M; Sterling, Jane C; Goon, Peter KC (2012). "HPV infection, anal intra-epithelial neoplasia (AIN) and anal cancer: current issues". BMC Cancer. 12 (1): 398. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-398. ISSN 1471-2407.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "Human papillomavirus (HPV)". World Health Organization. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ "Summary of the WHO Position Paper on Vaccines against Human Papillomavirus (HPV)" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2014. Retrieved 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Division of STD Prevention (1999). Prevention of genital HPV infection and sequelae: report of an external consultants' meeting. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ^ a b Schiffman M, Castle PE; Castle (August 2003). "Human papillomavirus: epidemiology and public health". Arch Pathol Lab Med. 127 (8): 930–4. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2003)127<930:HPEAPH>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1543-2165. PMID 12873163.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N; Jacobs; Manos; Bosch; Kummer; Shah; Snijders; Peto; Meijer; Muñoz (1999). "Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide". J. Pathol. 189 (1): 12–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 10451482.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldstein MA, Goodman A, del Carmen MG, Wilbur DC; Goodman; Del Carmen, MG; Wilbur (March 2009). "Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10-2009. A 23-year-old woman with an abnormal Papanicolaou smear". N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (13): 1337–44. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc0810837. PMID 19321871.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sawaya, George F.; Kulasingam, Shalini; Denberg, Thomas; Qaseem, Amir (30 April 2015). "Cervical Cancer Screening in Average-Risk Women: Best Practice Advice From the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. doi:10.7326/M14-2426. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ a b c World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.12. ISBN 9283204298.

- ^ "BBC News - Gay men 'should get anti-cancer jab'". BBC News.

- ^ Open AIDS J. 2014 Sep 30;8:25-30. doi: 10.2174/1874613601408010025. eCollection 2014. Prevalence of Anogenital Warts in Men with HIV/AIDS and Associated Factors. de Camargo CC1, Tasca KI1, Mendes MB1, Miot HA2, de Souza Ldo R1

- ^ Kahn JA (July 2009). "HPV vaccination for the prevention of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (3): 271–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0806938. PMID 19605832.

- ^ EHPV.

- ^ Ghittoni, R; Accardi, R; Chiocca, S; Tommasino, M (2015), "Role of human papillomaviruses in carcinogenesis", Ecancermedicalscience, 9 (526), doi:10.3332/ecancer.2015.526, PMC 4431404, PMID 25987895

- ^ Bzhalava, D; Guan, P; Franceschi, S; Dillner, J; Clifford, G (2013), "A systematic review of the prevalence of mucosal and cutaneous human papillomavirus types", Virology, 445 (1–2): 224–31, doi:10.1016/j.virol.2013.07.015, PMID 23928291.

- ^ a b Chaturvedi, Anil; Maura L. Gillison (4 March 2010). "Human Papillomavirus and Head and Neck Cancer". In Andrew F. Olshan (ed.). Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Prevention of Head and Neck Cancer (1st ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-1471-2.

- ^ Muñoz, N; Bosch, F. X.; De Sanjosé, S; Herrero, R; Castellsagué, X; Shah, K. V.; Snijders, P. J.; Meijer, C. J.; International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group (2003), "Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer", The New England Journal of Medicine, 348 (6): 518–27, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021641, PMID 12571259.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Mitchell, Richard (2007). "Chapter 19 The Female Genital System and Breast". Robbins Basic Pathology (8 ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Palefsky, Joel M.; Holly, Elizabeth A.; Ralston, Mary L.; Jay, Naomi (February 1988). "Prevalence and Risk Factors for Human Papillomavirus Infection of the Anal Canal in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)–Positive and HIV-Negative Homosexual Men" (PDF). Departments of Laboratory Medicine, Stomatology, and Epidemiology Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco. The Journal of Infectious Diseases Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ a b Muñoz N, Castellsagué X, de González AB, Gissmann L; Castellsagué; De González (2006). "Chapter 1: HPV in the etiology of human cancer". Vaccine. 24 (3): S1–S10. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.115. PMID 16949995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Parkin DM (2006). "The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002". Int. J. Cancer. 118 (12): 3030–44. doi:10.1002/ijc.21731. PMID 16404738.

- ^ http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/768633_slide

- ^ a b Ault KA (2006). "Epidemiology and Natural History of Human Papillomavirus Infections in the Female Genital tract". Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006: 1–5. doi:10.1155/IDOG/2006/40470. PMC 1581465. PMID 16967912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kreimer, Aimee R.; Clifford, Gary M.; Boyle, Peter; Franceschi, Silvia (1 February 2005). "Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 14 (2): 467–475. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. ISSN 1055-9965. PMID 15734974.

- ^ a b D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, Westra WH, Gillison ML (2007). "Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (19): 1944–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa065497. PMID 17494927.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ridge JA, Glisson BS, Lango MN, et al. "Head and Neck Tumors" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 11 ed. 2008.

- ^ Parfenov, Michael. "Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111: 15544–15549. doi:10.1073/pnas.1416074111.

- ^ "Oral Cancer on the rise among non-smokers under 50" (PDF). California Dental Hygienists’ Association. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ Chaturvedi, Anil K.; Engels, Eric A.; Pfeiffer, Ruth M.; Hernandez, Brenda Y.; Xiao, Weihong; Kim, Esther; Jiang, Bo; Goodman, Marc T.; Sibug-Saber, Maria (10 November 2011). "Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States". Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 29 (32): 4294–4301. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. ISSN 1527-7755. PMC 3221528. PMID 21969503.

- ^ Greenblatt, R. J. (2005). "Human papillomaviruses: Diseases, diagnosis, and a possible vaccine". Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 27 (18): 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2005.09.001.

- ^ a b c d Sinal SH, Woods CR (2005). "Human papillomavirus infections of the genital and respiratory tracts in young children". Seminars in pediatric infectious diseases. 16 (4): 306–16. doi:10.1053/j.spid.2005.06.010. PMID 16210110.

- ^ Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D (2000). "Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92 (9): 709–20. doi:10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. PMID 10793107.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gillison ML (2006). "Human papillomavirus and prognosis of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: implications for clinical research in head and neck cancers". J. Clin. Oncol. 24 (36): 5623–5. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1829. PMID 17179099.

- ^ a b "HPV and Men — CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 3 April 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- ^ Frisch M, Smith E, Grulich A, Johansen C (2003). "Cancer in a population-based cohort of men and women in registered homosexual partnerships". Am. J. Epidemiol. 157 (11): 966–72. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg067. PMID 12777359.

However, the risk for invasive anal squamous carcinoma, which is believed to be caused by certain types of sexually transmitted human papillomaviruses, a notable one being type 16, was significantly 31-fold elevated at a crude incidence of 25.6 per 100,000 person-years.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, Browne L, Buchbinder S, Colfax G, Da Costa M, Darragh T, Benet DJ, Judson F, Koblin B, Mayer KH, Palefsky JM (2005). "Age-related prevalence of anal cancer precursors in homosexual men: the EXPLORE study". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97 (12): 896–905. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji163. PMID 15956651.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "AIDSmeds Web Exclusives : Pap Smears for Anal Cancer? — by David Evans". AIDSmeds.com. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Goldie SJ, Kuntz KM, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA, Palefsky JM (June 2000). "Cost-effectiveness of screening for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions and anal cancer in human immunodeficiency virus-negative homosexual and bisexual men". Am. J. Med. 108 (8): 634–41. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00349-1. PMID 10856411.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karagas MR, Waterboer T, Li Z, Nelson HH, Michael KM, Bavinck JN, Perry AE, Spencer SK, Daling J, Green AC, Pawlita M (2010). "Genus β human papillomaviruses and incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas of skin: population based case-control study". BMJ. 341: 2986. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2986. PMC 2900549. PMID 20616098.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lechner M, Frampton GM, Fenton T, Feber A, Palmer G, Jay A, Pillay N, Forster M, Cronin MT, Lipson D, Miller VA, Brennan TA, Henderson S, Vaz F, O'Flynn P, Kalavrezos N, Yelensky R, Beck S, Stephens PJ, Boshoff C; Boshoff, G. (2013). "Targeted next-generation sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma identifies novel genetic alterations in HPV+ and HPV- tumors". Genome Medicine. 5 (5): 49. doi:10.1186/gm453. PMID 23718828.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mayo Clinic.com, Common warts, http://www.mayoclinic.com/print/common-warts/DS00370/DSECTION=all&METHOD=print

- ^ De Koning MN, Quint KD, Bruggink SC, Gussekloo J, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Feltkamp MC, Quint WG, Eekhof JA (2014). "High prevalence of cutaneous warts in elementary school children and ubiquitous presence of wart-associated HPV on clinically normal skin". The British journal of dermatology. 172: 196–201. doi:10.1111/bjd.13216. PMID 24976535.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lountzis NI, Rahman O (2008). "Images in clinical medicine. Digital verrucae". N. Engl. J. Med. 359 (2): 177. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm071912. PMID 18614785.

- ^ MedlinePlus, Warts, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/warts.html#cat42 (general reference with links). Also, see

- ^ Greer CE, Wheeler CM, Ladner MB, Beutner K, Coyne MY, Liang H, Langenberg A, Yen TS, Ralston R (1995). "Human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution and serological response to HPV type 6 virus-like particles in patients with genital warts". J. Clin. Microbiol. 33 (8): 2058–63. PMC 228335. PMID 7559948.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Human Papillomavirus at eMedicine

- ^ a b c "Genital HPV Infection Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 April 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- ^ "Photos of larynx Papillomas — Voice Medicine, New York". Voicemedicine.com. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Wu R, Sun S, Steinberg BM (2003). "Requirement of STAT3 activation for differentiation of mucosal stratified squamous epithelium". Mol. Med. 9 (3–4): 77–84. doi:10.2119/2003-00001.Wu. PMC 1430729. PMID 12865943.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moore CE, Wiatrak BJ, McClatchey KD, Koopmann CF, Thomas GR, Bradford CR, Carey TE (1999). "High-risk human papillomavirus types and squamous cell carcinoma in patients with respiratory papillomas". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 120 (5): 698–705. doi:10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a91773. PMID 10229596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moore, Matthew (12 November 2007). "Tree man 'who grew roots' may be cured". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ a b Burchell AN, Winer RL, de Sanjosé S, Franco EL (August 2006). "Chapter 6: Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of genital HPV infection". Vaccine. 24 Suppl 3: S3/52–61. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.031. ISSN 0264-410X. PMID 16950018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schmitt M, Depuydt C, Benoy I, Bogers J, Antoine J, Arbyn M, Pawlita M; on behalf of the VALGENT study group (201) Prevalence and viral load of 51 genital human papillomavirus types and 3 subtypes. Int J Cancer doi:10.1002/ijc.27891

- ^ Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ (2003). "Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (6): 518–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021641. PMID 12571259.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Egendorf, Laura. Sexually Transmitted Diseases (At Issue Series). New York: Greenhaven Press, 2007.

- ^ a b c Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, Thompson P, McDuffie K, Shvetsov YB, Kamemoto LE, Killeen J, Ning L, Goodman MT (2008). "Transmission of human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (6): 888–894. doi:10.3201/eid1406.070616. PMC 2600292. PMID 18507898.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Appendix Table. HPV transmission events in male-female couples by anatomic site

- ^ a b Giuliano AR, Nielson CM, Flores R, Dunne EF, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss MR, Markowitz LE, Smith D, Harris RB (2007). "The Optimal Anatomic Sites for Sampling Heterosexual Men for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Detection: The HPV Detection in Men Study". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196 (8): 1146–1152. doi:10.1086/521629. PMID 17955432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, Xi LF, Cherne S, O'Reilly S, Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA (2010). "DETECTION OF GENITAL HPV TYPES IN FINGERTIP SAMPLES FROM NEWLY SEXUALLY ACTIVE FEMALE UNIVERSITY STUDENTS". Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 19 (7): 1682–1685. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0226. PMC 2901391. PMID 20570905.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Winer RL, Lee SK, Hughes JP, Adam DE, Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA (2003). "Genital human papillomavirus infection: Incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university students". American Journal of Epidemiology. 157 (3): 218–226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf180. PMID 12543621.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tay SK (July 1995). "Genital oncogenic human papillomavirus infection: a short review on the mode of transmission" (Free full text). Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 24 (4): 598–601. ISSN 0304-4602. PMID 8849195.

- ^ Pao CC, Tsai PL, Chang YL, Hsieh TT, Jin JY (March 1993). "Possible non-sexual transmission of genital human papillomavirus infections in young women". European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 12 (3): 221–222. doi:10.1007/BF01967118. ISSN 0934-9723. PMID 8389707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tay SK, Ho TH, Lim-Tan SK (August 1990). "Is genital human papillomavirus infection always sexually transmitted?" (Free full text). The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 30 (3): 240–242. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1990.tb03223.x. ISSN 0004-8666. PMID 2256864.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sonnex C, Strauss S, Gray JJ (October 1999). "Detection of human papillomavirus DNA on the fingers of patients with genital warts". Sexually transmitted infections. 75 (5): 317–319. doi:10.1136/sti.75.5.317. ISSN 1368-4973. PMC 1758241. PMID 10616355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hans Krueger; Gavin Stuart; Richard Gallagher; Dan Williams, Jon Kerner (12 April 2010). HPV and Other Infectious Agents in Cancer:Opportunities for Prevention and Public Health: Opportunities for Prevention and Public Health. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-973291-3. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Bodaghi S, Wood LV, Roby G, Ryder C, Steinberg SM, Zheng ZM (November 2005). "Could human papillomaviruses be spread through blood?". J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 (11): 5428–34. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.11.5428-5434.2005. PMC 1287818. PMID 16272465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chen AC, Keleher A, Kedda MA, Spurdle AB, McMillan NA, Antonsson A (October 2009). "Human papillomavirus DNA detected in peripheral blood samples from healthy Australian male blood donors". J. Med. Virol. 81 (10): 1792–6. doi:10.1002/jmv.21592. PMID 19697401.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Eligibility Criteria by Topic - American Red Cross".

- ^ a b "Human Papillomavirus: Confronting the Epidemic—A Urologist's Perspective". nih.gov.

- ^ a b c Schiller JT, Day PM, Kines RC (2010). "Current understanding of the mechanism of HPV infection". Gynecologic Oncology. 118 (1 Suppl): S12. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.04.004. PMC 3493113. PMID 20494219.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Scheurer ME, Tortolero-Luna G, Adler-Storthz K (2005). "Human papillomavirus infection: biology, epidemiology, and prevention". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 15 (5): 727–746. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00246.x. PMID 16174218.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chen Z, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Desalle R, Anastos K, Segondy M, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Gravitt PE, Hsing AW, Burk RD (2011). "Evolution and Taxonomic Classification of Human Papillomavirus 16 (HPV16)-Related Variant Genomes". PloS ONE. 6 (5): 1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020183. PMID 21673791.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zuna RE, Tuller E, Wentzensen N, Mathews C, Allen RA, Shanesmith R, Dunn ST, Gold MA, Wang SS, Walker J, Schiffman M (2011). "HPV16 Variant Lineage, Clinical Stage, And Survivalin Women With Invasive Cervical Cancer". Infectious Agents & Cancer. 6: 19–27. doi:10.1186/1750-9378-6-19. PMID 22035468.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ganguly N, Parihar SP (2009). "Human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncoproteins as risk factors for tumorigenesis". Journal of biosciences. 34 (1): 113–123. doi:10.1007/s12038-009-0013-7. PMID 19430123.

- ^ Zheng ZM, Baker CC (2006). "Papillomavirus genome structure, expression, and post-transcriptional regulation". Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 11: 2286–2302. doi:10.2741/1971. PMC 1472295. PMID 16720315.

- ^ Tang S, Tao M, McCoy JP, Zheng ZM (2006). "The E7 Oncoprotein is Translated from Spliced E6*I Transcripts in High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Type 16- or Type 18-Positive Cervical Cancer Cell Lines via Translation Reinitiation". Journal of Virology. 80 (9): 4249–4263. doi:10.1128/JVI.80.9.4249-4263.2006. PMC 1472016. PMID 16611884.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Münger K, Howley PM (2002). "Human papillomavirus immortalization and transformation functions". Virus research. 89 (2): 213–228. doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00190-9. PMID 12445661.

- ^

Conway MJ, Alam S, Ryndock EJ, Cruz L, Christensen ND, Roden RB, Meyers C (October 2009). "Tissue-spanning redox gradient-dependent assembly of native human papillomavirus type 16 virions". Journal of Virology. 83 (20): 10515–26. doi:10.1128/JVI.00731-09. PMC 2753102. PMID 19656879.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bryan JT, Brown DR (March 2001). "Transmission of human papillomavirus type 11 infection by desquamated cornified cells". Virology. 281 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0777. PMID 11222093.

- ^ Rampias T, Boutati E, Pectasides E, Sasaki C, Kountourakis P, Weinberger P, Psyrri A (2010). "Activation of Wnt signaling pathway by human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncogenes in HPV16-positive oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma cells". Molecular cancer research : MCR. 8 (3): 433–443. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0345. PMID 20215420.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Hou SY, Wu SY, Chiang CM (2002). "Transcriptional Activity among High and Low Risk Human Papillomavirus E2 Proteins Correlates with E2 DNA Binding". Journal of Biologycal Chemistry. 277 (47): 45619–45629. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206829200. PMID 12239214.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Desaintes C, Goyat S, Garbay S, Yaniv M, Thierry F (1999). "Papillomavirus E2 induces p53-independent apoptosis in HeLa cells". Oncogene. 18 (32): 4538±4545. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202818. PMID 10467398. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Desaintes C, Demeret C, Goyat S, Yaniv M, Thierry F (1997). "Expression of the papillomavirus E2 protein in HeLa cells leads to apoptosis". The EMBO Journal. 16 (3): 504–514. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.3.504. PMC 1169654. PMID 9034333.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Watson RA (2005). "Human Papillomavirus: Confronting the Epidemic—A Urologist's Perspective". Reviews in Urology. 7 (3): 135–44. PMC 1477576. PMID 16985824.

- ^ Giuliano AR, Lu B, Nielson CM, Flores R, Papenfuss MR, Lee JH, Abrahamsen M, Harris RB (2008). "Age‐Specific Prevalence, Incidence, and Duration of Human Papillomavirus Infections in a Cohort of 290 US Men". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (6): 827–835. doi:10.1086/591095. PMID 18657037.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gavillon N, Vervaet H, Derniaux E, Terrosi P, Graesslin O, Quereux C (2010). "Papillomavirus humain (HPV) : comment ai-je attrapé ça ?". Gynécologie Obstétrique & Fertilité. 38 (3): 199–204. doi:10.1016/j.gyobfe.2010.01.003. PMID 20189438.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Human Papillomavirus Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases". CDC.gov. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Human papillomavirus vaccines. WHO position paper" (PDF). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 84 (15): 118–31. April 2009. PMID 19360985.

- ^ a b Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER (March 2007). "Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (Cervical Cancer Screening Among Vaccinated Females)". MMWR Recomm Rep. 56 (RR–2): 1–24 [17]. PMID 17380109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simon R. M. Dobson, MD; et al. (1 May 2013). "Immunogenicity of 2 Doses of HPV Vaccine in Younger Adolescents vs 3 Doses in Young Women A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 309 (17): 1793–1802. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Harper DM (2009). "Current prophylactic HPV vaccines and gynecologic premalignancies". Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 21 (6): 457–464.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Marcia G. Yerman (28 December 2010). "An Interview with Dr. Diane M. Harper, HPV Expert". Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "HPV Virus: Information About Human Papillomavirus". WebMD.

- ^ http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/g/gardasil/gardasil_pi.pdf

- ^ Yvonne Deleré; et al. (September 2014). "The Efficacy and Duration of Vaccine Protection Against Human Papillomavirus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 111: 35–36. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV" (press release). 10 December 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "CDC — Condom Effectiveness — Male Latex Condoms and Sexually Transmitted Diseases". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 October 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ "Information About What is Human Papillomavirus (HPV)?". City of Toronto Public Health Agency. September 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/lab-bio/res/psds-ftss/papillome-eng.php

- ^ "National Cancer Institute Fact Sheet: HPV and Cancer". Cancer.gov. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ a b "FDA Approval of cobas HPV Test – P1000020". U.S Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ a b Wright TC, Stoler MH, Sharma A, Zhang G, Behrens C, Wright TL (2011). "Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for the triage of women with high-risk HPV+ cytology-negative results". Am J Clin Pathol. 136 (4): 578–586. doi:10.1309/ajcptus5exas6dkz. PMID 21917680.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Digene HPV HC2 DNA Test Qiagen HPV test

- ^ "Qiagen to Buy Digene, Maker of Tests for Cancer-Causing Virus". The New York Times. 4 June 2007.

- ^ "So Close Together for So Long, and Now One". The Washington Post. 20 August 2007.

- ^ "An Error Occurred Setting Your User Cookie". thelancet.com.

- ^

Wentzensen N, von Knebel Doeberitz M (2007). "Biomarkers in cervical cancer screening". Dis. Markers. 23 (4): 315–30. doi:10.1155/2007/678793. PMID 17627065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Molden T, Kraus I, Skomedal H, Nordstrøm T, Karlsen F (June 2007). "PreTect HPV-Proofer: real-time detection and typing of E6/E7 mRNA from carcinogenic human papillomaviruses". J. Virol. Methods. 142 (1–2): 204–12. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.01.036. PMID 17379322.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ FDA approval of APTIMA HPV Assay - P100042

- ^ Dockter J, Schroder A, Hill C, Guzenski L, Monsonego J, Giachetti C (2009). "Clinical performance of the APTIMA® HPV Assay for the detection of high-risk HPV and high-grade cervical lesions". Journal of Clinical Virology. 45: S55–S61. doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(09)70009-5. PMID 19651370.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Press". gen-probe.com.