Robert Schumann: Difference between revisions

m Undid revision 1224137761 by Tim riley (talk)rev own change |

additional info and refs; rem uncited material |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|German composer, pianist and critic (1810–1856)}} |

{{Short description|German composer, pianist and critic (1810–1856)}} |

||

{{Redirect|Schumann|the French statesman|Robert Schuman|other uses|Schumann (disambiguation)}} |

{{Redirect|Schumann|the French statesman|Robert Schuman|other uses|Schumann (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox person |

{{Infobox person |

||

| name = |

| name =Robert Schumann |

||

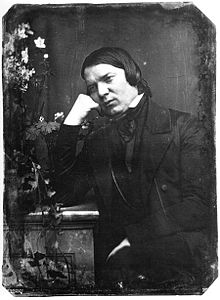

| image = Robert |

| image = Robert Schumann 1839.jpg |

||

|alt=young white man in 1830s costume; he has wavy dark hair of medium length and is clean-shaven |

|||

| caption = Robert Schumann |

|||

| caption = Schumann in 1839 by [[Josef Kriehuber]] |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1810|6|8|df=yes}} |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1810|6|8|df=yes}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Zwickau]], [[Kingdom of Saxony]] |

| birth_place = [[Zwickau]], [[Kingdom of Saxony]] |

||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

| death_place = [[Bonn]], Rhine Province, [[Prussia]] |

| death_place = [[Bonn]], Rhine Province, [[Prussia]] |

||

| occupation = {{hlist|Composer|Pianist|Music critic}} |

| occupation = {{hlist|Composer|Pianist|Music critic}} |

||

| works = [[List of compositions by Robert Schumann|List of compositions]] |

|||

| spouse = {{Marriage|[[Clara Schumann]]|1840}} |

| spouse = {{Marriage|[[Clara Schumann]]|1840}} |

||

| signature = Signature Robert Schumann-2.jpg |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Robert Schumann'''{{refn|Many sources from the 19th century onwards state that Schumann had the middle name Alexander,<ref>Liliencron, p. 44; Spitta, p. 384; Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3234; and Wolff p. 1702</ref> but according to the 2001 edition of ''[[Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians]]'' and a 2005 biography by Eric Frederick Jensen there is no evidence that he had a middle name and it is possibly a misreading of his teenage pseudonym "Skülander". His birth and death certificates and all other existing official documents give "Robert Schumann" as his only names.<ref name=grove>[[John Daverio|Daverio, John]] and [[Eric Sams]]. [https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40704 "Schumann, Robert"], ''Grove Music Online'', Oxford University Press, 2001 {{subscription}}</ref><ref>Jensen, p. 2</ref>|group=n|name=alexander}} ({{IPA-de|ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈʃuːman|lang}}; 8 June 1810{{spaced ndash}}29 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the Romantic era. Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Schumann was unsure whether to pursue a career as a lawyer or to make a living as a pianist-composer. He studied law at Leipzig and Heidelberg Universities but his main interests were music and [[Romantic literature]]. From 1829 he was a student of the piano teacher [[Friedrich Wieck]], but his hopes for a career as a virtuoso pianist were frustrated by a growing problem with his right hand, and he concentrated on composition. His early works were mainly piano pieces, including the large-scale ''[[Carnaval (Schumann)|Carnaval]]'' (1834–35) In 1834 he was a co-founder of the {{lang|de|Neue Zeitschrift für Musik}} (New Musical Journal) which he edited for ten years. In his writing for the journal and in his music he distinguished between two contrasting aspects of his personality, dubbing them "Florestan" for his impetuous self and "Eusebius" for his gentle poetic side. |

|||

'''Robert Schumann'''{{efn|According to Daverio, there is no evidence of the middle name "Alexander", which appears in some sources. It is possibly a corruption of his teenage pseudonym "Skülander".{{sfn|Daverio|Sams|2001}}}} ({{IPA-de|ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈʃuːman|lang}}; 8 June 1810{{spaced ndash}}29 July 1856) was a German [[composer]], pianist, and influential [[music critic]]. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career as a [[virtuoso]] pianist. His teacher, [[Friedrich Wieck]], a German pianist, had assured him that he could become the finest pianist in Europe, but a hand injury ended this dream. Schumann then focused his musical energies on composing. |

|||

In 1840 Schumann married Wieck's daughter [[Clara Schumann|Clara]], despite the bitter opposition of her father, who did not regard Schumann as a suitable husband for her.. The marriage was followed by prolific composing, first of songs and song‐cycles including {{lang|de|[[Frauen-Liebe und Leben|Frauenliebe und Leben]]}} ("Woman's Love and Life") and {{lang|de|[[Dichterliebe]]}} ("Poet's Love"). In 1841 he turned his attention to orchestral music, and in the following two years to chamber music and choral works. |

|||

In 1840, Schumann married [[Friedrich Wieck]]'s daughter [[Clara Schumann|Clara Wieck]], after a long and acrimonious legal battle with Friedrich, who opposed the marriage. A lifelong partnership in music began, as Clara herself was an established pianist and music prodigy. Clara and Robert also developed a close relationship with German composer [[Johannes Brahms]]. |

|||

Schumann and Clara toured Russia in 1844, after which his physical and mental health was poor for some months. The couple moved to [[Dresden]], living there until 1850. In 1846 Clara gave the first performance of his [[Piano Concerto (Schumann)| Piano Concerto]] and their friend [[Felix Mendelssohn]] conducted the premiere of Schumann's [[Symphony No. 2 (Schumann)|Second Symphony]]. In 1850 the Schumanns moved to [[Düsseldorf]] in the hope that his appointment as the town's director of music would provide financial stability, but he was not a good conductor and had to resign after three years. In 1853 the Schumanns met the twenty-year old [[Johannes Brahms]], whom Schumann praised in an article in the{{lang|de|Neue Zeitschrift für Musik}}. The following year Schumann's always precarious mental health deteriorated gravely. He threw himself into Rhine but was rescued and taken to a private sanatorium where he lived another two-and-a-half years, dying there at the age of 46. |

|||

Until 1840, Schumann wrote exclusively for the piano. Later, he composed piano and orchestral works, and many [[Lied]]er (songs for voice and piano). He composed four [[Symphony|symphonies]], one opera, and other orchestral, [[choral]], and [[chamber music|chamber]] works. His best-known works include ''[[Carnaval (Schumann)|Carnaval]]'', ''[[Symphonic Studies (Schumann)|Symphonic Studies]]'', ''[[Kinderszenen]]'', ''[[Kreisleriana]]'', and the ''[[Fantasie in C (Schumann)|Fantasie in C]]''. Schumann was known for infusing his music with characters through motifs, as well as references to works of literature. These characters bled into his editorial writing in the ''[[Neue Zeitschrift für Musik]]'' (New Journal for Music), a [[Leipzig]]-based publication that he co-founded. |

|||

Schumann was recognised in his lifetime for his piano music – often [[program music|programmatic]] – and his songs. His other works were less generally admired, and for many years there was a widespread belief that those from his later years lacked the inspiration of his early music. More recently this view has been less prevalent, but it is still for his piano works and songs from the 1830s and 1840s that he is most esteemed. |

|||

Schumann suffered from a [[mental disorder]] that first manifested in 1833 as a severe [[melancholic depression|melancholic depressive]] episode—which recurred several times alternating with phases of "exaltation" and increasingly also delusional ideas of being poisoned or threatened with metallic items. What is now thought to have been a combination of [[bipolar disorder]] and perhaps [[mercury poisoning]] led to "manic" and "depressive" periods in Schumann's compositional productivity. After a suicide attempt in 1854, Schumann was admitted at his own request to a [[Psychiatric hospital|mental asylum]] in [[Endenich]] (now in [[Bonn]]). Diagnosed with ''psychotic [[melancholia]]'', he died of pneumonia two years later at the age of 46, without recovering from his mental illness. |

|||

== |

== Life and career == |

||

=== |

=== Childhood === |

||

[[File:Schumannhaus ALT.JPG|thumb| |

[[File:Schumannhaus ALT.JPG|thumb|upright=1.25|alt=Exterior of substantial town house seen from the square outside it|Schumann's birthplace, now the [[Robert Schumann House]], after an anonymous colourised lithograph]] |

||

Robert Schumann{{refn|group=n|name=alexander}} was born in [[Zwickau]], in the [[Kingdom of Saxony]] (today the state of [[Saxony]]), into an affluent middle class family.<ref name=perrey6>Perrey, Schumann's lives, p. 6</ref> On 13 June 1830 the local newspaper, the {{lang|de|Zwickauer Wochenblatt}} (Zwickau Weekly Paper), carried the announcement, "On 8 June to Herr [[August Schumann]], notable citizen and bookseller here, a little son".<ref>Dowley, p. 7</ref> He was the fifth and last child of August Schumann and his wife, Johanna Christiane (née Schnabel). August, not only a bookseller but also a lexicographer, author and publisher of chivalric romances, made considerable sums from his German translations of writers such as [[Cervantes]], [[Walter Scott]] and [[Lord Byron]].<ref name=grove/> Robert, his favourite child, was able to spend many hours exploring the classics of literature in his father's collection.<ref name=grove/> Intermittently, between the ages of three and five-and-a-half, he was placed with foster parents, as his mother had contracted [[typhus]].<ref name=perrey6/> |

|||

Schumann was born in [[Zwickau]], in the [[Kingdom of Saxony]] (today the state of [[Saxony]]), the fifth and last child of Johanna Christiane (née Schnabel) and [[August Schumann]].<ref>{{harvnb|Ostwald|1985|p=11}}</ref> Schumann began to compose before the age of seven, but his boyhood was spent in the cultivation of literature as much as music—undoubtedly influenced by his father, a bookseller, publisher, and novelist.<ref>{{harvnb|Schumann|1982}}</ref> |

|||

At the age of six Schumann went to a private preparatory school, where he remained for four years.<ref name=c3>Chissell, p. 3</ref> When he was seven he began studying general music and piano with the local organist, Johann Gottfried Kuntsch, and for a time he also had cello and flute lessons with one of the municipal musicians, Carl Gottlieb Meissner.<ref>Geck, p. 8</ref> Throughout his childhood and youth his love of music and literature ran in tandem, with poems and dramatic works produced alongside small-scale compositions, mainly piano pieces and songs.<ref name=hall1125>Hall, p. 1125</ref> He was not a musical child prodigy like [[Mozart]] or [[Felix Mendelssohn|Mendelssohn]],<ref name=perrey6/> but his talent as a pianist was evident from an early age: in 1850 the {{lang|de|Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung}} (Universal Musical Journal) printed a biographical sketch of Schumann which included an account from contemporary sources that even as a boy he possessed a special talent for portraying feelings and characteristic traits in melody: |

|||

At age seven, Schumann began studying general music and piano with Johann Gottfried Kuntzsch, a teacher at the Zwickau high school. The boy immediately developed a love of music, and worked on his own compositions without the aid of Kuntzsch. Even though he often disregarded the principles of musical composition, he created works regarded as admirable for his age; he later recalled in his autobiography having produced 'dances'. The ''Universal Journal of Music'' 1850 supplement included a biographical sketch of Schumann that noted, "It has been related that Schumann, as a child, possessed rare taste and talent for portraying feelings and characteristic traits in melody,—ay, he could sketch the different dispositions of his intimate friends by certain figures and passages on the piano so exactly and comically that everyone burst into loud laughter at the similitude of the portrait."<ref>[[Eric Himy]], pianist, Recording ''Homage to Schumann'', CD Notes, (Centaur, 2006), CEN 2858</ref> |

|||

{{blockindent|Indeed, he could sketch the different dispositions of his intimate friends by certain figures and passages on the piano so exactly and comically that everyone burst into loud laughter at the accuracy of the portrait.<ref>Wasielewski, p. 11</ref>|}} |

|||

From 1820 Schumann attended the Zwickau Lyceum, the local high school of about two hundred boys, where he remained till the age of eighteen, studying a traditional curriculum. In addition to his studies he read extensively: among his early enthusiasms were [[Friedrich Schiller|Schiller]] and [[Jean Paul]].<ref>Geck, p. 49</ref> According to the musical historian George Hall, Paul remained Schumann's favourite author and exercised a powerful influence on the composer's creativity with his sensibility and vein of fantasy.<ref name=hall1125/> Musically, Schumann got to know the works of [[Haydn]], Mozart, [[Beethoven]], and of living composers [[Carl Maria von Weber|Weber]], with whom August Schumann tried unsuccessfully to arrange for Robert to study.<ref name=hall1125/> August was not particularly musical but he encouraged his son's interest in music, buying him a [[Johann Baptist Streicher|Streicher]] grand piano and organising expeditions to [[Leipzig]] for a performance of ''[[Die Zauberflöte]]'' and [[Karlovy Vary|Carlsbad]] to hear the celebrated pianist [[Ignaz Moscheles]].<ref>Chissell, p. 4</ref> |

|||

[[File:Portrait of A Young Age of Robert Schumann.png|alt=portrait of a young man|thumb|The young Schumann, {{Circa|1826}}<ref>{{Cite web |title=Portraits Robert Schumann |url=https://www.schumann-zwickau.de/de/03/03/portraits-robert-schumann.php |access-date=26 April 2023 |website=Willkommen in der Robert-Schumann-Stadt Zwickau! |language=de}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Pin on Products |url=https://www.pinterest.com/pin/portrait-at-young-age-of-robert-schumann-giclee-print--56506170327082242/ |access-date=26 April 2023 |website=Pinterest |language=en}}</ref>]] |

|||

At age 14, Schumann wrote an essay on the aesthetics of music and also contributed to a volume, edited by his father, titled ''Portraits of Famous Men''. While still at school in Zwickau, he read the works of the German poet-philosophers [[Friedrich Schiller|Schiller]] and [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe|Goethe]], as well as [[Lord Byron|Byron]] and the [[Tragedy#Ancient Greek tragedy|Greek tragedians]]. His most powerful and permanent literary inspiration was [[Jean Paul]], a German writer whose influence is seen in Schumann's youthful novels ''Juniusabende'', completed in 1826, and ''Selene''. |

|||

[[File:Portrait of A Young Age of Robert Schumann.png|thumb|Schumann {{circa|1826}}|alt=miniature oil painting of a young, clean-shaven white youth in early-19th-century costume]] |

|||

Schumann's interest in music was sparked by attending a performance of [[Ignaz Moscheles]] playing at [[Karlovy Vary|Karlsbad]], and he later developed an interest in the works of [[Ludwig van Beethoven|Beethoven]], [[Franz Schubert|Schubert]], and [[Felix Mendelssohn|Mendelssohn]]. His father, who had encouraged his musical aspirations, died in 1826 when Schumann was 16. Thereafter, neither his mother nor his guardian encouraged him to pursue a music career. In 1828, Schumann left high school, and after a trip during which he met the poet [[Heinrich Heine]] in Munich, he left to study law at the University of Leipzig under family pressure. But in Leipzig Schumann instead focused on improvisation, song composition, and writing novels. He also began to seriously study piano with [[Friedrich Wieck]], a well-known piano teacher. In 1829, he continued his law studies in [[Heidelberg]], where he became a lifelong member of [[Corps Saxo-Borussia Heidelberg]]. |

|||

=== |

===University=== |

||

August Schumann died in 1826; his widow was less enthusiastic about a musical career for her son and persuaded him to study for the law as a profession. After his final examinations at the Lyceum in March 1828 he entered [[Leipzig University]]. Accounts differ about his diligence as a law student. According to his room-mate Emil Flechsig, he never set foot in a lecture hall,<ref name=grove/> but he himself recorded, "I am industrious and regular, and enjoy my jurisprudence ... and am only now beginning to appreciate its true worth".<ref>Chissell, p. 16</ref> Nonetheless reading and playing the piano occupied a good deal of his time, and he developed expensive tastes for champagne and cigars.<ref name=hall1125/> Musically, he discovered the works of [[Franz Schubert]], whose death in November 1828 caused Schumann to cry all night.<ref name=hall1125/> The leading piano teacher in Leipzig was [[Friedrich Wieck]], who recognised Schumann's talent and accepted him as a pupil.<ref>Jensen, p. 22</ref> |

|||

[[File:Robert Schumann 1830.png|thumb|upright|left|Schumann in 1830]] |

|||

[[File:Robert-Schumann-Haus.JPG|thumb|upright|Schumann's music room in the Robert Schumann House, Zwickau]] |

|||

During [[Eastertide]] 1830, he heard the Italian violinist, violist, guitarist, and composer [[Niccolò Paganini]] play in [[Frankfurt]]. In July he wrote to his mother, "My whole life has been a struggle between Poetry and Prose, or call it Music and Law." With her permission, by Christmas he was back in Leipzig, at age 20 taking piano lessons from his old master [[Friedrich Wieck]], who assured him that he would be a successful concert pianist after a few years' study with him.<ref>{{harvnb|Perrey|2007|p=11}}</ref> Some stories claim that, during his studies with Wieck, Schumann permanently injured a finger on his right hand. Wieck claimed that Schumann damaged his finger by using a mechanical device that held back one finger while he exercised the others—which was supposed to strengthen the weakest fingers.<ref name="Jensen 2001">{{harvnb|Jensen|2001}}</ref> [[Clara Schumann]] discredited the story, saying the disability was not due to a mechanical device, and Robert Schumann himself referred to it as "an affliction of the whole hand." Some argue that, as the disability appeared to have been chronic and have affected the hand, and not just a finger, it was not likely caused by a finger-strengthening device.<ref>{{cite journal| jstor= 954772 | first= Eric| last= Sams | title= Schumann's hand injury| journal= The Musical Times| volume= 112| pages= 1156–1159| number= 1546 |date= December 1971| doi= 10.2307/954772}}</ref> In 2012, neurologists discussed Schumann's symptoms at a conference called "Musicians With [[Dystonia]]."<ref>{{Cite news|last=Oestreich|first=James R.|date=13 March 2012|title=A Disorder That Stops the Music|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/arts/music/dystonia-which-struck-glenn-gould-and-other-musicians.html}}</ref> |

|||

After a year in Leipzig Schumann convinced his mother that he should move to the [[University of Heidelberg]] which, unlike Leipzig, offered courses in Roman, ecclesiastical and international law (as well as reuniting Schumann with his close friend Eduard Röller who was a student there).<ref>Dowley, p. 27</ref> After matriculating at the university on 30 July 1829 he travelled in Switzerland and Italy from late August to late October. He was greatly taken with [[Rossini]]'s operas and the [[bel canto]] of the soprano [[Giuditta Pasta]]; he wrote to Wieck, "one can have no notion of Italian music without hearing it under Italian skies".<ref name=grove/> Another influence on him was hearing the violin virtuoso [[Niccolò Paganini]] play in Frankfurt in April 1830.<ref>Taylor, p. 58</ref> In the words of one biographer, "The easy-going discipline at Heidelberg University helped the world to lose a bad lawyer and to gain a great musician".<ref>[https://www.jstor.org/stable/905534 "Robert Schumann"], ''The Musical Times'', Vol. 51, No. 809 (1 July 1910), pp. 426</ref> Finally deciding in favour of music rather than the law as a career he wrote to his mother on 30 July 1830 telling her how he saw his future: "My entire life has been a twenty-year struggle between poetry and prose, or call it music and law".<ref>Jensen, p. 34</ref> He persuaded her to ask Wieck for an objective assessment of his musical potential. Wieck's verdict was that with the necessary hard work Schumann could become a leading pianist within three years. A six-month trial period was agreed.<ref>Jensen, p. 37</ref> |

|||

Schumann abandoned the idea of a concert career and devoted himself instead to composition. To this end he began a study of music theory under [[Heinrich Dorn]], a German composer six years his senior and, at that time, conductor of the [[Leipzig Opera]]. |

|||

=== |

===1830s=== |

||

[[File:Schumann-Abegg-theme.jpg|thumb|upright=2|Opening of Schumann's [[Opus number|Op.]] 1, the [[Abegg Variations]]|alt=musical score for solo piano piece]] |

|||

Later in 1830 Schumann published his [[Opus number|Op.]] 1, [[Variations on the name "Abegg"|a set of piano variations]] on a theme based on the name of its supposed dedicatee, Countess Pauline von Abegg (who was almost certainly a product of Schumann's imagination).<ref>Geck, p. 62; and Jensen, p. 97</ref> The notes A-B-E-G-G, played in waltz tempo, make up the theme on which the variations are based.<ref>Taylor, p. 72</ref> The use of a musical cipher became a recurrent characteristic of Schumann's later music.<ref name=hall1125/> In 1831 he began lessons in harmony and counterpoint with Heinrich Dorn, musical director of the Saxon court theatre,<ref>Jensen, p. 64</ref> and in 1832 he published his Op. 2, {{lang|fr|[[Papillons]]}} (Butterflies) for piano, a [[program music|programmatic piece]] depicting twin brothers – one a poetic dreamer, the other a worldly realist – both in love with the same woman at a masked ball.<ref>Taylor, p. 74</ref> Schumann had by now come to regard himself as having two distinct sides to his personality and art: he dubbed his introspective, pensive self "Eusebius" and the impetuous and dynamic ''[[alter ego]]'' "Florestan".<ref>Dowley, p. 46</ref> |

|||

[[File:Neue-Zeitschrift-fur-Musik.jpg|thumb|left|upright|{{lang|de|Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik}}, edited by Schumann from 1835|alt=Front page of text of newspaper in old style Gothic German type]] |

|||

Schumann's fusion of literary ideas with musical ones—known as [[program music]]—may have first taken shape in ''[[Papillons]]'', Op. 2 (''Butterflies''), a musical portrayal of events in [[Jean Paul]]'s novel ''Flegeljahre''. In a letter from Leipzig dated April 1832, Schumann bids his brothers, "Read the last scene in Jean Paul's ''Flegeljahre'' as soon as possible, because the ''Papillons'' are intended as a musical representation of that masquerade." This inspiration is foreshadowed to some extent in his first written criticism—an 1831 essay on [[Frédéric Chopin]]'s [[Variations on "Là ci darem la mano" (Chopin)|variations on a theme]] from [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]]'s ''[[Don Giovanni]]'', published in the ''[[Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung]]''. In it, Schumann creates imaginary characters who discuss Chopin's work: Florestan (the embodiment of Schumann's passionate, voluble side) and Eusebius (his dreamy, introspective side)—the counterparts of Vult and Walt in ''Flegeljahre.'' They call on a third, Meister Raro, for his opinion. Raro may represent either the composer himself, Wieck's daughter [[Clara Schumann|Clara]], or the combination of the two (Cla'''ra''' + '''Ro'''bert). |

|||

Schumann's pianistic ambitions were ended by a growing stiffness in the middle finger of his right hand. The early symptoms had come while he was still a student at Heidelberg, and the cause is uncertain.<ref name=ostwald/>{{refn|Wieck believed the damage was done by Schumann's use of a chiroplast – a finger-stretching device then favoured by pianists; the biographer [[Eric Sams]] has theorised that the affliction was caused by [[mercury poisoning]] as a side effect of treatment for [[syphilis]], a hypothesis subsequently discounted by neurologists.<ref name=ostwald>Ostwald, pp. 23 and 25</ref>|group=n}} He tried all the treatments then in vogue including [[allopathy]], [[homeopathy]], and electric therapy, but without success.<ref name=b2>Slonimsky and Kuhn, pp. 3234–3235</ref> The condition had the advantage of exempting him from compulsory military service – he could not fire a rifle<ref name=b2/> – but by 1832 he recognised that a career as a virtuoso pianist was impossible and he shifted his main focus to composition. He completed further sets of small piano pieces and the first movement of a symphony (too thinly orchestrated according to Wieck).<ref name=grove/> An additional activity was journalism. From March 1834, along with Wieck and others, he was on the editorial board of a new music magazine, {{lang|de|Neue Leipziger Zeitschrift für Musik}} (New Leipzig Music Magazine), which was reconstituted under his sole editorship in January 1835 as the {{lang|de|Neue Zeitschrift für Musik}}.<ref name=grove/> Hall writes that it took "a thoughtful and progressive line on the new music of the day".<ref name=hall1126>Hall, p. 1126</ref> Among the contributors were friends and colleagues of Schumann, writing under pen names: he included them in his {{lang|de|[[Davidsbündler]]}} (League of David) – a band of fighters for musical truth who warred with the Philistines – a product of the composer's imagination in which, blurring the boundaries of imagination and reality, he included his musical friends.<ref name=hall1126/> |

|||

In the winter of 1832, at age 22, Schumann visited relatives in Zwickau and [[Schneeberg, Saxony|Schneeberg]], where he performed the first movement of his ''Symphony in G minor'' (without opus number, known as the "Zwickauer"). In Zwickau, the music was performed at a concert given by Clara Wieck, who was then just 13 years old. On this occasion Clara played bravura Variations by [[Henri Herz]], a composer whom Schumann was already deriding as a philistine.<ref>Robert Schumann, musical Journal</ref> Schumann's mother said to Clara, "You must marry my Robert one day."<ref>{{harvnb|Litzmann|1913}}</ref> The ''Symphony in G minor'' was not published during Schumann's lifetime but has been played and recorded in recent times. |

|||

During 1835 Schumann met three musicians whom he regarded with particular respect: [[Mendelssohn]], [[Moscheles]] and [[Chopin]].<ref name=chron1>Perrey, Chronology, p. xiv</ref> Early in that year he completed two substantial compositions: ''[[Carnaval (Schumann)|Carnaval]]'', Op.9 and the [[Symphonic Studies]], Op.13. These works grew out of his romantic relationship with Ernestine von Fricken, a fellow pupil of Wieck. The musical themes of ''Carnaval'' derive from the name of her home town, [[Aš|Asch]]. The Symphonic Studies are based on a melody said to be by Ernestine's father, Baron von Fricken, an amateur flautist.<ref name=grove/> Schumann and Ernestine became secretly engaged, but in the view of the musical scholar [[Joan Chissell]], during 1835 Schumann gradually realised that Ernestine's personality was not as interesting as he first thought, and this, together with his discovery that she was an illegitimate, impecunious, adopted daughter of Fricken, brought the affair to a gradual end.<ref>Chissell, p. 36</ref> |

|||

The 1833 deaths of Schumann's brother Julius and his sister-in-law Rosalie in the [[Second cholera pandemic (1829-1851)|worldwide cholera pandemic]] brought on a [[Major depressive disorder|severe depressive]] episode. |

|||

[[File:Clara-Wieck-1832-signed-illegible.png|thumb|upright|[[Clara Schumann|Clara Wieck]] in 1832|alt=Young white woman, in white gown, with elaborately arranged dark hair, seated and looking towards the artist]] |

|||

Schumann felt a growing attraction to Wieck's daughter, the sixteen-year-old [[Clara Schumann|Clara]]. She was her father's star pupil, a piano virtuoso with a growing reputation and emotionally mature beyond her years.<ref name=c37/> According to Chissell, her concerto debut at the [[Leipzig Gewandhaus]] on 9 November 1835, with [[Felix Mendelssohn]] conducting, "set the seal on all her earlier successes, and there was now no doubting that a great future lay before her as a pianist".<ref name=c37>Chissell, p. 37</ref> Schumann had watched her career approvingly since she was nine, but only now fell in love with her. His feelings were reciprocated: they declared their love to each other in January 1836.<ref>Chissell, p. 38</ref> Schumann expected that Wieck would welcome the proposed marriage, but he was mistaken: Wieck refused his consent, fearing that Schumann would be unable to provide for his daughter, that she would have to abandon her career, and that she would be legally required to relinquish her inheritance to her husband.<ref>Geck, p. 98</ref> It took a series of acrimonious legal actions over the next four years for Schumann to obtain a court ruling that he and Clara were free to marry without her father's consent.<ref name=grove/> |

|||

[[File:Robert Schumann in youth.jpg|thumb|upright|left|A youthful Robert Schumann]] |

|||

Professionally the later years of the 1830s were marked by an abortive attempt by Schumann to establish himself in Vienna, and the beginning of an important friendship with Mendelssohn, who was by then based in Leipzig, conducting the [[Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra|Gewandhaus Orchestra]] and also by an increasing output of piano works including ''[[Kreisleriana]]'' (1837) {{lang|de|[[Kinderszenen]]}} (Scenes from Childhood, 1838) and {{lang|de|[[Faschingsschwank aus Wien]]}} (Carnival Prank from Vienna, 1839).<ref name=hall1126/> In 1838 Schumann visited Schubert's brother Ferdinand and discovered several manuscripts including that of the [[Symphony No. 9 (Schubert)|Great C major Symphony]].<ref name=chron2>Perrey, Chronology, p. xv</ref> Ferdinand allowed him to take a copy away and Schumann arranged for the work's world premiere, conducted by Mendelssohn in Leipzig on 21 March 1839.<ref>Marston, p. 51</ref> In the {{lang|de|Neue Zeitschrift für Musik}} Schumann wrote enthusiastically about the work and described its "{{lang|de|himmlische Länge}}" – its "heavenly length" – a phrase that has become common currency in later analyses of the symphony.<ref>Maintz, p. 100; and Marston, p. 51</ref> |

|||

==== ''Neue Zeitschrift für Musik'' ==== |

|||

===1840s=== |

|||

By spring 1834, Schumann had sufficiently recovered to inaugurate ''[[Neue Zeitschrift für Musik|Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik]]'' ("New Journal for Music"), first published on 3 April 1834. In his writings, Schumann created a fictional music society based on people in his life, called the ''[[Davidsbündler]]'', named after the biblical King David who fought against the Philistines. Schumann published most of his critical writings in the journal, and often lambasted the popular taste for flashy technical displays from figures whom Schumann perceived as inferior composers, or "philistines". Schumann campaigned to revive interest in major composers of the past, including [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]], [[Ludwig van Beethoven|Beethoven]], and [[Carl Maria von Weber|Weber]]. He also promoted the work of some contemporary composers, including [[Frédéric Chopin|Chopin]] (about whom Schumann famously wrote, "Hats off, Gentlemen! A genius!")<ref>[[Vladimir Ashkenazy]]'s notes, Favourite Chopin</ref> and [[Hector Berlioz|Berlioz]], whom he praised for creating music of substance. On the other hand, Schumann disparaged the school of [[Franz Liszt|Liszt]] and [[Richard Wagner|Wagner]]. Among Schumann's associates at this time were composers [[Norbert Burgmüller]] and [[Ludwig Schuncke]] (to whom Schumann dedicated his ''Toccata in C'').{{sfn|Schumann|1965}}{{sfn|Schumann|1982}} |

|||

Schumann and Clara finally married on 12 September 1840, the day before her twenty-first birthday.<ref>Dowley, p. 66</ref> Hall writes that marriage gave Schumann "the emotional and domestic stability on which his subsequent achievements were founded".<ref name=hall1126/> Clara made some sacrifices in marrying Schumann: as a pianist of international reputation she was the better-known of the two but her career was continually interrupted by motherhood of their seven children. She inspired Schumann in his composing career, encouraging him to extend his range as a composer beyond solo piano works.<ref name=hall1126/> During 1840 Schumann turned his attention to song, producing more than half his total output of {{lang|de|Lieder}}, including the cycles {{lang|de|[[Myrthen]]}} ("Myrtles", a wedding present for Clara), {{lang|de|[[Frauen-Liebe und Leben|Frauenliebe und Leben]]}} ("Woman's Love and Life"), {{lang|de|[[Dichterliebe]]}} ("Poet's Love"), and settings of words by [[Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff|Joseph von Eichendorff]] and [[Heinrich Heine]] and others.<ref name=hall1126/> |

|||

In 1841 Schumann focused on orchestral music. On 31 March his [[Symphony No. 1 (Schumann)|First Symphony]], ''The Spring'', was premiered by Mendelssohn at a concert in the Gewandhaus at which Clara played Chopin's [[Piano Concerto No. 2 (Chopin)|Second Piano Concerto]] and some of Schumann's works for solo piano.<ref>Dowley, p. 74</ref> Then came the [[Overture, Scherzo and Finale]], the Phantasie for piano and orchestra (which later became the first movement of the [[Piano Concerto (Schumann)|Piano Concerto]]) and a new symphony (eventually published as the [[Symphony No. 4 (Schumann)|Fourth, in D minor]]). Clara gave birth to a daughter in September, the first of the Schumanns' seven children to survive.<ref name=hall1126/> |

|||

==== ''Carnaval'' ==== |

|||

[[File:Clara und Robert Schumann Relief MIM.jpg|thumb|upright|Medallion commemorating the Schumanns, 1846|alt=commemorative silver-coloured medallion showing left profiles of Clara and Robert Schumann]] |

|||

The following year Schumann turned his attention to chamber music. He studied works by Haydn and Mozart, despite an ambiguous attitude to the former: "Today it is impossible to learn anything new from him. He is like a familiar friend of the house whom all greet with pleasure and with esteem, but who has ceased to arouse any particular interest".<ref>Schumann, p. 94</ref> He was stronger in his praise of Mozart: "Serenity, repose, grace, the characteristics of the antique works of art, are also those of Mozart's school. The Greeks gave to 'The Thunderer' a radiant expression, and radiantly does Mozart launch his lightnings".<ref>Schumann, pp. 94–95</ref> After his studies Schumann produced three string quartets, a [[Piano Quintet (Schumann)|Piano Quintet]] and a [[Piano Quartet (Schumann)|Piano Quartet]].<ref name=hall1126/> |

|||

1843 began with a setback to Schumann's career: he had a severe and debilitating mental crisis. This was not the first such attack, although it was the worst so far. Hall writes that he had been subject to similar attacks at intervals over a long period, and speculates that the condition may have been congenital, affecting Schumann's father and younger sister.<ref name=hall1126/> Later in the year, Schumann, having recovered, completed a successful secular [[oratorio]], {{lang|de|[[Das Paradies und die Peri]]}} (Paradise and the [[Peri]]), based on an oriental poem by [[Thomas Moore]]. It was premiered at the Gewandhaus on 4 December and repeat performances followed at Dresden on 23 December, Berlin early the following year, and in London in June 1856, when Schumann's friend [[William Sterndale Bennett]] conducted a performance given by the [[Royal Philharmonic Society|Philharmonic Society]] before [[Queen Victoria]] and the [[Prince Consort]].<ref>Browne Conor. [https://blogs.qub.ac.uk/erin/2017/05/31/robert-schumanns-das-paradies-und-die-peri-and-its-early-performances/ "Robert Schumann's Das Paradies und die Peri and its early Performances"], ''Thomas Moore in Europe'', Queen’s University Belfast, 31 May 2017; and "Philharmonic Concerts", ''The Times'', 24 June 1856, p. 12</ref> Although neglected after Schumann's death it remained popular throughout his lifetime and brought his name to international attention.<ref name=hall1126/> During 1843 Mendelssohn invited him to teach piano and composition at the new [[Leipzig Conservatory]],<ref name=chron3>Perrey, Chronology, p. xvi</ref> and Wieck approached him with an offer of reconciliation.<ref name=b2/> Schumann gladly accepted both, although the resumed relationship with his father-in-law remained polite rather than close.<ref name=b2/> |

|||

''[[Carnaval (Schumann)|Carnaval]]'', Op. 9 (1834) is one of Schumann's most characteristic piano works. Schumann begins nearly every section of ''Carnaval'' with a [[musical cryptogram]], the musical notes signified in German by the letters that spell [[Aš|Asch]] (A, E-flat, C, and B, or alternatively A-flat, C, and B; in German these are A, Es, C and H, and As, C and H respectively), the [[Bohemia]]n town in which Ernestine was born, and the notes are also the musical letters in Schumann's own name. Eusebius and Florestan, the imaginary figures appearing so often in his critical writings, also appear, alongside brilliant imitations of Chopin and Paganini. To each of these characters he devotes a section of ''Carnaval''. The work comes to a close with a march of the ''Davidsbündler''—the league of [[King David]]'s men against the [[Philistines]]—in which may be heard the clear accents of truth in contest with the dull clamour of falsehood embodied in a [[Musical quotation|quotation]] from the seventeenth century ''[[Grossvatertanz|Grandfather's Dance]]''. The march, a step nearly always in duple meter, is here in 3/4 time (triple meter). The work ends in joy and a degree of mock-triumph. In ''Carnaval'', Schumann went further than in ''Papillons'', by conceiving the story as well as the musical representation (and also displaying a maturation of compositional resource). |

|||

[[File:Robert u Clara Schumann 1847.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Robert and Clara Schumann in 1847, lithograph with a personal dedication|alt=Signed engraving of middle-aged white couple seated and looking towards the camera. The man is clean-shaven; the woman's dark hair is tied in a bun]] |

|||

In 1844 Clara embarked on a concert tour of Russia; Schumann joined her. It was an artistic and financial success, and they were both immensely impressed by Saint Petersburg and Moscow,<ref name=grove/><ref>Daverio, p. 286</ref> but the tour was arduous and by the end Schumann was in a poor state both physically and mentally.<ref name=grove/> After he and Clara returned to Leipzig in late May he sold the ''Neue Zeitschrift'', and in December the family moved to Dresden. Schumann had been passed over for the conductorship of the Leipzig Gewandhaus in succession to Mendelssohn, and he thought that Dresden, with a thriving opera house, might be the place where he could, as he now wished, become an operatic composer. His health remained poor. His doctor in Dresden reported complaints "from insomnia, general weakness, auditory disturbances, tremors, and chills in the feet, to a whole range of phobias".<ref>Daverio, p. 299</ref> |

|||

From the beginning of 1845 Schumann's health began to improve; he and Clara studied [[counterpoint]] together and both produced contrapuntal works for the piano. He added a slow movement and finale to the 1841 Phantasie for piano and orchestra, to create his Piano Concerto, Op 54.<ref>Daverio, p. 305</ref> The following year he worked on what was to be published as his [[Symphony No. 2 (Schumann)|Second Symphony]], Op. 61. Progress on the work was slow, interrupted by further bouts of ill health.<ref>Daverio, p. 298</ref> When the symphony was complete he began work on his opera, ''[[Genoveva]]'', which was not completed until August 1848.<ref>Walker, p. 93</ref> |

|||

==== Relationships ==== |

|||

Between 24 November 1846 and 4 February 1847 the Schumanns toured in Vienna, Berlin and other cities. The Viennese leg of the tour was not a success. The performance of Schumann's First Symphony and Piano Concerto at the {{lang|de|[[Musikverein]]|italic=no}} on 1 January 1847 attracted a sparse and unenthusiastic audience, but in Berlin the performance of ''Das Paradies und die Peri'' was well received, and the tour gave Schumann the chance to see numerous operatic productions. In the words of ''[[Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians]]'', "A regular if not always approving member of the audience at performances of works by [[Donizetti]], Rossini, [[Meyerbeer]], [[Fromental Halévy|Halévy]] and [[Friedrich von Flotow|Flotow]], he registered his 'desire to write operas' in his travel diary".<ref name=grove/> The Schumanns suffered several blows during 1847, including the death of their first son, Emil, born the year before, and the deaths of their friends Felix and [[Fanny Mendelssohn|Fanny]] Mendelssohn.<ref name=chron2/> A second son, Ludwig, and a third, Ferdinand, were born in 1848 and 1849.<ref name=chron2/> |

|||

During the summer of 1834 Schumann became engaged to 16-year-old Ernestine von Fricken, the adopted daughter of a rich Bohemian-born noble. In August 1835, he learned that Ernestine was born illegitimate, which meant that she would have no dowry. Fearful that her limited means would force him to earn his living like a "day-labourer," Schumann completely broke with her toward the end of the year. He felt a growing attraction to 15-year-old Clara Wieck. They made mutual declarations of love in December in Zwickau, where Clara appeared in concert. His budding romance with Clara was disrupted when her father learned of their trysts during the Christmas holidays. He summarily forbade them further meetings, and ordered all their correspondence burnt. |

|||

=== |

===1850s=== |

||

[[File:Schumann-photo1850.jpg|thumb|upright=1|Schumann in an 1850 [[daguerreotype]]|alt=early photograph of a middle-aged white man, clean shaven, seated, leaning on the hand of his right arm, of which the elbow is on the adjacent table]] |

|||

On 3 October 1835, Schumann met [[Felix Mendelssohn]] at Wieck's house in Leipzig, and his enthusiastic appreciation of that artist<ref>{{harvnb|Daverio|1997|p=134}}</ref> was shown with the same generous freedom that distinguished his acknowledgement of the greatness of Chopin and other colleagues, and later prompted him to publicly pronounce the then-unknown [[Johannes Brahms]] a genius. |

|||

''Genoveva'', a four-act opera based on the medieval legend of [[Genevieve of Brabant]], was premiered in Leipzig, conducted by the composer, in June 1850. There were two further performances immediately afterwards, but the piece was not the success Schumann had been hoping for. In a 2005 study of the composer, Eric Frederick Jensen attributes this to Schumann's operatic style: "not tuneful and simplistic enough for the majority, not 'progressive' enough for the [[Richard Wagner|Wagnerians]]".<ref>Jensen, p. 235</ref> [[Liszt]], who was in the first-night audience, revived ''Genoveva'' at [[Weimar]] in 1855 – the only other production of the opera in Schumann's lifetime.<ref>Jensen, pp. 316–317</ref> Since then, according to ''[[The Complete Opera Book|Kobbé's Opera Book]]'', despite occasional revivals ''Genoveva'' has remained "far from even the edge of the repertory".<ref>Harewood, pp. 718–719</ref> |

|||

[[File:Andreas Staub - Clara Wieck (Lithographie 1839, cropped).jpg|alt=|left|thumb|[[Clara Wieck]] in an idealized lithograph by [[Andreas Staub]], c. 1839]] |

|||

[[File:Friedrich Wieck um 1838.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Friedrich Wieck]] in a sketch by [[Pauline Viardot-Garcia]], around 1838]] |

|||

With a large family to support, Schumann sought financial security and with the support of his wife he accepted a post as director of music at [[Düsseldorf]] in April 1850. Hall comments that in retrospect it can be seen that Schumann was fundamentally unsuited for the post: "His diffidence in social situations, allied to mental instability, ensured that initially warm relations with local musicians gradually deteriorated to the point where his removal became a necessity in 1853".<ref name=hall1127>Hall, p. 1127</ref> During 1850 Schumann composed two substantial late works – the [[Symphony No. 3 (Schumann)|Third (''Rhenish'') Symphony]] and the [[Cello Concerto (Schumann)|Cello Concerto]].<ref name=chron4>Perrey, Chronology, p. xvii</ref> He continued to compose prolifically, and reworked some of his earlier works, including the D minor symphony from 1841, published as his [[Symphony No. 4 (Schumann)|Fourth Symphony]] (1851) and the 1835 ''Symphonic Studies'' (1852).<ref name=chron4/> |

|||

In 1837 Schumann published his ''[[Symphonic Studies (Schumann)|Symphonic Studies]]'', a complex set of ''étude''-like variations written in 1834–1835, which demanded a finished piano technique. These variations were based on a theme by the adoptive father of Ernestine von Fricken. The work—described as "one of the peaks of the piano literature, lofty in conception and faultless in workmanship" [Hutcheson]—was dedicated to the young English composer [[William Sterndale Bennett]], for whom Schumann had had a high regard when they worked together in Leipzig.<ref name="Jensen 2001" /> |

|||

In 1853 the twenty-year-old [[Johannes Brahms]] called on Schumann with a letter of introduction from their mutual friend the violinist [[Joseph Joachim]]. When Brahms began playing one of his piano sonatas, Schumann excitedly rushed out of the room and came back leading his wife by the hand, saying "Now, my dear Clara, you will hear such music as you never heard before; and you, young man, play the work from the beginning".<ref>Walker, p. 110</ref> Schumann was so impressed that he wrote an article – his last – for the {{lang|de|Neue Zeitschrift für Musik}} titled "{{lang|de|Neue Bahnen|italic=no}}" (New Paths), extolling Brahms as a musician who was destined "to give expression to his times in ideal fashion".<ref>Schumann, pp. 252–254</ref> |

|||

The ''[[Davidsbündlertänze]]'', Op. 6, (also published in 1837 despite the low opus number) literally "Dances of the League of David", is an embodiment of the struggle between enlightened Romanticism and musical philistinism. Schumann credited the two sides of his character with the composition of the work (the more passionate numbers are signed F. (Florestan) and the more dreamy signed E. (Eusebius)). The work begins with the "motto of C. W." (Clara Wieck) denoting her support for the ideals of the ''Davidsbund''. The ''Bund'' was a music society of Schumann's imagination, members of which were kindred spirits (as he saw them) such as Chopin, Paganini and Clara, as well as the personalized Florestan and Eusebius.<ref name="Jensen 2001" /> |

|||

Hall writes that Brahms proved "a personal tower of strength to Clara during the difficult days ahead": in early 1854 Schumann's health deteriorated drastically. On 27 February he attempted suicide by throwing himself into the [[Rhine]].<ref name=hall1127/> He was rescued by fishermen, and at his own request he was admitted to a private sanatorium at [[Endenich]], near [[Bonn]], on 4 March. He remained there for more than two years, gradually deteriorating, with intermittent intervals of lucidity during which he wrote and received letters and sometimes essayed some composition.<ref name=grove/> The director of the sanatorium held that direct contact between patients and relatives was likely to distress all concerned and reduce the chances of recovery. Friends, including Brahms and Joachim, were permitted to visit Schumann but Clara did not see her husband until nearly two and a half years into his confinement, and only two days before his death.<ref name=grove/> Schumann died at the sanatorium aged 46 on 29 July 1856, the cause of death being recorded as [[pneumonia]].<ref>Daverio, p. 568</ref>{{refn|As with the hand ailment earlier in his life, Schumann's decline and death have been the subject of much conjecture. In ''Grove'', [[John Daverio]] and [[Eric Sams]] suggest tertiary [[syphilis]], long dormant, as the cause, and the official certification as death from pneumonia as intended to spare Clara's feelings.<ref name=grove/> This view is given varying degrees of credence by [[Joan Chissell]], [[Alan Walker (musicologist)|Alan Walker]] and Tim Dowley,<ref>Chissell, p. 77</ref><ref>Walker, p. 117</ref><ref>Dowley, p. 117</ref> and is not endorsed by Eric Frederick Jensen and [[Martin Geck]], who regard the evidence for syphilis as unconvincing.<ref>Jensen, p. 329</ref> <ref>Geck, p. 251</ref>|group=n}} |

|||

''[[Kinderszenen]]'', Op. 15, completed in 1838 and a favourite of Schumann's piano works, depicts the innocence and playfulness of childhood. The "Träumerei" in F major, No. 7 of the set, is one of the most famous piano pieces ever written, and has been performed in myriad forms and transcriptions. It has been the favourite [[Encore (concert)|encore]] of several great pianists, including [[Vladimir Horowitz]]. Melodic and deceptively simple, the piece is "complex" in its harmonic structure.<ref>[[Alban Berg]], replying to charges that modern music was overly complex, pointed out that ''Kinderszenen'' is constructed on a complex base.</ref> |

|||

==Works== |

|||

{{listen |

{{listen |

||

| header = [[Kreisleriana]], Op. 16 (1838) |

| header = [[Kreisleriana]], Op. 16 (1838) |

||

| Line 82: | Line 87: | ||

| description = [[Giorgi Latso]], piano |

| description = [[Giorgi Latso]], piano |

||

| format = [[Ogg]] |

| format = [[Ogg]] |

||

| image=none}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{listen |

{{listen |

||

| header = [[Fantasie in C (Schumann)|Fantasie C major]], Op. 17 (1836, revised 1839) |

| header = [[Fantasie in C (Schumann)|Fantasie C major]], Op. 17 (1836, revised 1839) |

||

| Line 99: | Line 104: | ||

| image = none |

| image = none |

||

}} |

}} |

||

''[[Kreisleriana]]'', Op. 16 (1838), considered one of Schumann's greatest works, carried his fantasy and emotional range deeper. [[Johannes Kreisler]] was a fictional musician created by poet [[E. T. A. Hoffmann]], and characterized as a "romantic brought into contact with reality." Schumann used the figure to express "fantastic and mad" emotional states. According to [[Ernest Hutcheson#Works|Hutcheson ("The Literature of the Piano")]], this work is "among the finest efforts of Schumann's genius. He never surpassed the searching beauty of the slow movements (Nos. 2, 4, 6) or the urgent passion of others (Nos. 1, 3, 5, 7) […] To appreciate it a high level of aesthetic intelligence is required […] This is no facile music, there is severity alike in its beauty and its passion." |

|||

The ''[[Fantasie in C (Schumann)|Fantasie in C]]'', Op. 17, composed in the summer of 1836, is a work of passion and deep pathos, imbued with the spirit of the late Beethoven. Schumann intended to use proceeds from sales of the work toward the construction of [[Beethoven Monument (Bonn)|a monument to Beethoven]], who had died in 1827. The first movement of the ''Fantasie'' contains a [[Musical quotation|musical quote]] from Beethoven's song cycle, ''[[An die ferne Geliebte]]'', Op. 98 (at the Adagio coda, taken from the last song of the cycle). The original titles of the movements were ''Ruins'', ''Triumphal Arch'', and ''The Starry Crown''. According to [[Franz Liszt]],<ref>Strelezki: ''Personal Recollections of Chats with Liszt''</ref> who played the work for Schumann and to whom it was dedicated, the ''Fantasie'' was apt to be played too heavily, and should have a dreamier (''träumerisch'') character than vigorous German pianists tended to impart. Liszt also said: "It is a noble work, worthy of Beethoven, whose career, by the way, it is supposed to represent".<ref>Anton Strelezki: ''Personal Recollections of Chats with Liszt''. London, 1893.</ref> Again, according to Hutcheson: "No words can describe the Phantasie, no quotations set forth the majesty of its genius. It must suffice to say that it is Schumann's greatest work in large form for piano solo."{{citation needed|date=December 2010}} |

|||

{{listen |

{{listen |

||

| header = [[Arabeske (Schumann)|Arabeske in C major, Op. 18 (1839)]] |

| header = [[Arabeske (Schumann)|Arabeske in C major, Op. 18 (1839)]] |

||

| filename = Schumann-arabeske-andrea-valori.ogg |

| filename = Schumann-arabeske-andrea-valori.ogg |

||

| title = Arabeske (Schumann) |

| title = Arabeske (Schumann) |

||

| description = |

| description = Mario Andrea Valori, piano |

||

| format = [[Ogg]] |

| format = [[Ogg]] |

||

| image=none}} |

|||

}} |

|||

''[[Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians]]'' (2001) begins its entry on Schumann: "[G]reat German composer of surpassing imaginative power whose music expressed the deepest spirit of the Romantic era", and concludes: "As both man and musician, Schumann is recognized as the quintessential artist of the Romantic era in German music. He was a master of lyric expression and dramatic power, perhaps best revealed in his outstanding piano music and songs ..."<ref name=baker>Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3234</ref><ref>Slonimsky and Kuhn, p. 3236</ref> |

|||

In the late nineteenth century and most of the twentieth it was widely held that the music of Schumann's later years was less inspired than his earlier works (up to about the mid-1840s), and that this was due to his declining health. More recently his later works have been viewed more favourably; Hall suggests that this is because they are now played more often in concert, are widely available on record, and have "the beneficial effects of period performance practice as it has come to be applied to mid-19th-century music".<ref name=hall1126/> |

|||

After a visit to [[Vienna]], during which he discovered [[Franz Schubert]]'s previously unknown [[Symphony No. 9 (Schubert)|Symphony No. 9 in C]], in 1839 Schumann wrote the ''[[Faschingsschwank aus Wien]]'' (''Carnival Prank from Vienna''). Most of the joke is in the central section of the first movement, which makes a thinly veiled reference to ''[[La Marseillaise]]''. (Vienna had banned the song due to harsh memories of [[Napoleon]]'s invasion.) The festive mood does not preclude moments of melancholic introspection in the Intermezzo. |

|||

=== |

===Solo piano=== |

||

Although Schumann's works in some other musical genres have had a mixed critical reception, both during his lifetime and since, there is widespread agreement about the high quality of his solo piano music.<ref name=hall1125/> In his youth the [[Classical period (music)|classical]] tradition of [[Bach]], Mozart and [[Beethoven]] was temporarily eclipsed by a fashion for the flamboyant showpieces of composers such as [[Ignaz Moscheles]]. Schumann's first published work, the Abegg Variations, is in that style.<ref name=grove/> But he revered the earlier German masters, and in his three piano sonatas (composed between 1830 and 1836) and the [[Fantasie in C (Schumann)|Fantasie in C]] (1836) he showed his respect for the earlier German tradition.<ref>Solomon, pp. 41–42</ref> [[Absolute music]] such as those works are in the minority in his piano compositions, of which many are what Hall calls "character pieces with fanciful names".<ref name=hall1126/> |

|||

{{Redirect|Year of Song|the Alexander Armstrong album|A Year of Songs}} |

|||

From 1832 to 1839, Schumann wrote almost exclusively for piano, but in 1840 alone he wrote at least 138 songs. Indeed, 1840 (the ''Liederjahr'' or ''year of song'') is highly significant in Schumann's musical legacy, despite his earlier deriding of works for piano and voice as inferior. |

|||

Schumann's most characteristic form in his piano music is the cycle of short, interrelated pieces, often [[program music|programmatic]], such as {{lang|de|[[Carnaval (Schumann)|Carnaval]], [[Fantasiestücke, Op. 12|Fantasiestücke]], [[Kreisleriana]], [[Kinderszenen|Kinderszenen]]}} and {{lang|de|[[Waldszenen|Waldszenen]]}}. [[J. A. Fuller Maitland]] wrote of the first of these, "Of all the pianoforte works [it] is perhaps the most popular; its wonderful animation and never-ending variety ensure the production of its full effect, and its great and various difficulties make it the best possible test of a pianist's skill and versatility".<ref>Fuller Maitland, p. 52</ref> Schumann continually inserted into his piano works veiled allusions to himself and others – particularly Clara – in the form of [[ciphers]] and musical quotations.<ref name=grove/> His self-references include both the "Florestan" and the "Eusebius" elements he identified in himself.<ref>Chissell, p. 88</ref> |

|||

[[File:Leipzig Schumann-Haus.jpg|thumb|[[Schumann House, Leipzig]]: Robert and Clara Schumann lived in an apartment here from 1840 to 1844.]] |

|||

After a long and acrimonious legal battle with her father, Schumann married Clara Wieck in the [[Gedächtniskirche Schönefeld|Schönefeld church]] in [[Leipzig-Schönefeld]], on 12 September 1840, the day before her 21st birthday. Had they waited another day, they would no longer have required her father's consent. Their marriage supported a remarkable business partnership, with Clara acting as an inspiration, critic, and confidante to her husband. Despite her delicate appearance, she was an extremely strong-willed and energetic woman, who kept up a demanding schedule of concert tours in between bearing several children. Two years after their marriage, Friedrich Wieck at last reconciled himself with the couple, eager to see his grandchildren. |

|||

Although some of his music is technically challenging for the pianist Schumann also wrote simpler pieces for young players, the best-known of which are his ''[[Album for the Young]]'' (1848) and Three Sonatas for Young People (1853).<ref name=hall1125/> He also wrote some undemanding music with an eye to commercial sales, including the {{lang|de|[[Blumenstück (Schumann)|Blumenstück]]}} (Flower Piece) and {{lang|de|[[Arabeske (Schumann)|Arabeske]]}} (both 1839), which he privately considered "feeble and intended for the ladies".<ref>Jensen, p. 170</ref> |

|||

Prior to the legal case and subsequent marriage, the lovers exchanged love letters and held secret rendezvous. Robert often waited for hours in a cafe in a nearby city just to see Clara for a few minutes after one of her concerts. The strain of this long courtship and its consummation may have led to this great outpouring of Lieder (vocal songs with piano accompaniment). This is evident in ''Widmung'', for example, where he uses the melody from [[Franz Schubert|Schubert's]] [[Ave Maria (Schubert)|''Ave Maria'']] in the postlude in homage to Clara. Schumann's biographers attribute the sweetness, doubt, and despair of these songs to the emotions aroused by his love for Clara and the uncertainties of their future together. |

|||

===Songs=== |

|||

Robert and Clara had eight children, Emil (1846–1847), who died at 1 year; Marie (1841–1929); Elise (1843–1928); Julie (1845–1872); Ludwig (1848–1899); Ferdinand (1849–1891); [[Eugenie Schumann|Eugenie]] (1851–1938); and Felix (1854–1879). |

|||

The authors of ''[[The Record Guide]]'' describe Schumann as "one of the four supreme masters of the German Lied", alongside Schubert, Brahms and [[Hugo Wolf]].<ref name=st686>Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 686</ref> He wrote more than 300 songs for voice and piano.<ref name=gj/> They are known for the quality of the texts he set: Hall comments that the composer's youthful appreciation of literature was constantly renewed in adult life.<ref name=hsong>Hall, pp. 1126–1127</ref> Although Schumann greatly admired Goethe and Schiller and set a few of their verses, his favoured poets for lyrics were the later romantics such as [[Heinrich Heine|Heine]], [[Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff|Eichendorff]] and [[Eduard Mörike|Mörike]].<ref name=st686/> |

|||

Among the best-known of the songs are those in four cycles composed in 1840 – a year Schumann called his {{lang|de|Liederjahr}} (year of song).<ref name=f251>Ferris, p. 251</ref> These are {{lang|de|[[Dichterliebe]]}} (Poet's Love) comprising sixteen songs with words by Heine; {{lang|de|[[Frauen-Liebe und Leben#Schumann's setting|Frauenliebe und Leben]]}} (Woman's Love and Life), eight songs setting poems by [[Adelbert von Chamisso]]; and two sets simply titled {{lang|de|Liederkreis}} – German for "Song Cycle" – the [[Liederkreis, Op. 24 (Schumann)|Op. 24]] set, consisting of nine Heine settings and the [[Liederkreis, Op. 39 (Schumann)|Op. 39]] set of twelve settings of poems by Eichendorff.<ref name=grove/> Also from 1840 is the set Schumann wrote as a wedding present to Clara, {{lang|de|[[Myrthen]]}} (Myrtles – traditionally part of a bride's wedding bouquet),<ref>Finson (2007), p. 21</ref> which the composer called a song cycle, although with twenty-six songs with lyrics from ten different writers this set is a less unified cycle than the others. In a study of Schumann's songs [[Eric Sams]] suggests that even here there is a unifying theme, namely the composer himself.<ref>Sams, p. 50</ref> |

|||

[[File:Robert and Clara Schumann.jpg|thumb|The stylized profiles of Clara and Robert Schumann, after the well-known relief by [[Ernst Friedrich August Rietschel]]]] |

|||

[[File:Du Ring am meinem Finger.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.65|Opening of "{{lang|de|Du Ring am meinen Finger|italic=no}}" from {{lang|de|[[Frauen-Liebe und Leben|Frauenliebe und Leben]]}}|alt=Musical score with line for voice and two lines below for piano accompaniment]] |

|||

Although during the twentieth century it became common practice to perform these cycles as a whole, in Schumann's time and beyond it was usual to extract individual songs for performance in recitals. The first documented public performance of a complete Schumann song cycle was not until 1861, five years after the composer's death; the [[baritone]] [[Julius Stockhausen]] sang {{lang|de|Dichterliebe}} with Brahms at the piano.<ref name=r222>Reich p. 222</ref> Stockhausen also gave the first complete performances of {{lang|de|Frauenliebe und Leben}} and the Op. 24 {{lang|de|Liederkreis}}.<ref name=r222/> |

|||

His chief song-cycles in this period were settings of the ''[[Liederkreis, Op. 39|Liederkreis]]'' of [[Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff|Joseph von Eichendorff]], Op. 39 (depicting a series of moods relating to or inspired by nature); the ''[[Frauenliebe und -leben]]'' of [[Adelbert von Chamisso|Chamisso]], Op. 42 (relating the tale of a woman's marriage, childbirth and widowhood); the ''[[Dichterliebe]]'' of [[Heinrich Heine|Heine]], Op. 48 (depicting a lover rejected, but coming to terms with his painful loss through renunciation and forgiveness); and ''[[Myrthen]]'', a collection of songs, including poems by Goethe, [[Friedrich Rückert|Rückert]], Heine, Byron, [[Robert Burns|Burns]] and Moore. The songs ''Belsatzar'', Op. 57 and ''Die beiden Grenadiere'', Op. 49, both to Heine's words, show Schumann at his best as a ballad writer, although the dramatic ballad is less congenial to him than the introspective lyric. The Op. 35, 40 and 98a sets (words by [[Justinus Kerner]], Chamisso and Goethe respectively), although less well known, also contain songs of lyric and dramatic quality. |

|||

After his {{lang|de|Liederjahr}} Schumann returned in earnest to writing songs after a break of several years. Hall describes the the variety of the songs as immense, and comments that some of the later songs are entirely different in mood from the composer's earlier Romantic settings. Schumann's literary sensibilities led him to create in his songs an equal partnership between words and music unprecedented in the German {{lang|de|Lied}}.<ref name=hsong/> His affinity with the piano is heard in his accompaniments to his songs, notably in their preludes and postludes, the latter often summing up what has been heard in the song.<ref name=hsong/> |

|||

===Orchestral=== |

|||

[[File:Rhenish-opening-score.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|Opening of [[Symphony No. 3 (Schumann)|Schumann's Third Symphony]], the "Rhenish"|alt=page of full orchestral score]] |

|||

Schumann acknowledged that he found orchestration a difficult art to master, and many analysts have criticised his orchestral writing.<ref name=grove/> Conductors including [[Gustav Mahler]], [[Max Reger]], [[Otto Klemperer]] and [[George Szell]] have made changes to the instrumentation before conducting his orchestral music.<ref>Heyworth, p. 36; Kapp, p. 239; and [https://www.gramophone.co.uk/review/schumann-symphonies-manfred-overture "Schumann Symphonies; Manfred – Overture"], ''Gramophone'', February 1997</ref> The music scholar [[Julius Harrison]] considers such alterations fruitless: "the essence of Schumann's warmly vibrant music resides in its forthright romantic appeal with all those personal traits, lovable characteristic and faults" that make up Schumann's artistic character.<ref>Harrison, p. 249</ref> Hall comments that a trend towards performing the orchestral music with smaller forces than the modern symphony orchestra and using [[historically informed performance]] practice has helped Schumann's orchestration appear in a more favourable light.<ref name=hall1127/> |

|||

After the successful premiere of the [[Symphony No. 1 (Schumann)|first]] of his four symphonies (1841) the {{lang|de|Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung}} described it as "well and fluently written ... also, for the most part, knowledgeably, tastefully, and often quite successfully and effectively orchestrated",<ref>Finson (1989), p. 1</ref> although a later critic called it "inflated piano music with mainly routine orchestration".<ref>[[Gerald Abraham|Abraham, Gerald]], ''quoted'' in Burnham, p. 152</ref> Later in the year a second symphony was premiered and was less enthusiastically received. Schumann revised it ten years later and published it as his [[Symphony No. 4 (Schumann)|Fourth Symphony]] although Brahms preferred the original, more lightly-scored version.<ref>Harrison, p. 247</ref> The latter is occasionally performed and has been recorded, but the revised 1851 score is more usually played.<ref>March, ''et al'', pp. 1139–1140</ref> The work now called the [[Symphony No. 2 (Schumann)|Second Symphony]] (1846) is structurally the most formal of the four and is influenced by Beethoven and Schubert.<ref>Harrison, pp. 252–253</ref> The [[Symphony No. 3 (Schumann)|Third Symphony]] (1851), known as the ''Rhenish'', is, unusually for a symphony of its day, in five movements, and is the composer's nearest approach to pictorial symphonic music, with movements depicting a solemn religious ceremony in [[Cologne Cathedral]] and outdoor merrymaking of Rhinelanders.<ref>Harrison, p. 255</ref> |

|||

Schumann experimented with unconventional symphonic forms in 1841 in his [[Overture, Scherzo and Finale]], Op. 52, sometimes described as "a symphony without a slow movement".<ref>Burnham, p. 157; and Abraham, p. 53</ref> Its unorthodox structure may have made it less appealing and it is not often performed.<ref>Burnham, p. 158</ref> Schumann composed six overtures, three of them for theatrical performance, preceding [[Lord Byron|Byron]]'s ''[[Manfred]]'' (1852), [[Goethe]]'s [[Scenes from Goethe's Faust|''Faust'']] (1853) and his own ''Genoveva''. The other three were stand-alone concert works inspired by by Schiller (''[[The Bride of Messina]]''), Shakespeare (''[[Julius Caesar (play)|Julius Caesar]]'') and Goethe (''[[Hermann and Dorothea]]'').<ref>Burnham, pp. 163–164</ref> |

|||

The [[Piano Concerto (Schumann)|Piano Concerto]] (1845) quickly became and has remained one of the most popular of Romantic piano concertos.<ref name=tomes/> In the mid-twentieth century, when the symphonies were less well regarded than they later became, the concerto was described in ''[[The Record Guide]]'' as "the one large-scale work of Schumann's which is by general consent an entire success".<ref>Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 678</ref> The pianist Susan Tomes comments, "In the era of recording it has often been paired with [[Piano Concerto (Grieg)|Grieg's Piano Concerto]] (also in A minor) which clearly shows the influence of Schumann's".<ref name=tomes>Tomes, p. 126</ref> The first movement pitches against each other the forthright Florestan and dreamy Eusebius elements in Schumann's artistic nature – the vigorous opening bars succeeded by the wistful A minor theme that enters in the fourth bar.<ref name=tomes/> No other concerto or concertante work by Schumann has approached the popularity of the piano concerto, but the [[Konzertstück for Four Horns and Orchestra|Concert Piece for Four Horns and Orchestra]] (1849) and the [[Cello Concerto (Schumann)|Cello Concerto]] (1850) remain in the concert repertoire and are well represented on record.<ref>March ''et al'', pp. 1134, 1138 and 1140</ref> The late [[Violin Concerto (Schumann)|Violin Concerto]] (1853) is less often heard but has received several recordings.<ref>March ''et al'', p. 1137</ref> |

|||

===Chamber=== |

|||

{{listen |

{{listen |

||

| header = Andante and Variations, Op. 46 (1843)<br /> |

| header = Andante and Variations, Op. 46 (1843)<br /> |

||

| filename = Robert Schumann - Andante and Variations - Introduction, Theme and Variations 01-05.ogg |

| filename = Robert Schumann - Andante and Variations - Introduction, Theme and Variations 01-05.ogg |

||

| title = Introduction, Theme and Variations 1–5 |

| title = Introduction, Theme and Variations 1–5 |

||

| Line 142: | Line 156: | ||

| title3 = Variations 11–15 |

| title3 = Variations 11–15 |

||

| format3 = [[ogg]] |

| format3 = [[ogg]] |

||

| description3 =Performed by Neal and Nancy O'Doan (pianos), Carter Enyeart and Toby Saks (cellos) and Christopher Leuba (horn) |

|||

| description3 = |

|||

| image = none |

| image = none |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Schumann composed a substantial quantity of chamber pieces, of which the best-known and most performed are the [[Piano Quintet (Schumann)|Piano Quintet in E{{music|flat}} major]], Op. 44, the [[Piano Quartet (Schumann)|Piano Quartet]] in the same key (both 1842) and three piano trios, the [[Piano Trio No. 1 (Schumann)|first]] and [[Piano Trio No. 2 (Schumann)|second]] from 1847 and the [[Piano Trio No. 3 (Schumann)|third]] from 1851. The quintet became a template for other nineteenth-century composers. Schumann's writing for piano and [[string quartet]] – two violins, one viola and one cello – was in contrast with earlier piano quintets with different combinations of instruments, such as Schubert's ''[[Trout Quintet]]'' (1819). Schumann's ensemble became the template for later composers including Brahms, [[César Franck|Franck]], [[Gabriel Fauré|Fauré]], [[Dvořák]] and [[Elgar]].<ref>[https://imslp.org/wiki/List_of_Compositions_for_Piano_Quintet "List of Compositions for Piano Quintet"], International Music Score Library Project. Retrieved 17 May 2024</ref> |

|||

In 1841 he wrote two of his four symphonies, [[Symphony No. 1 (Schumann)|No. 1 in B-flat]], Op. 38, ''Spring'' and [[Symphony No. 4 (Schumann)|No. 4 in D minor]] (the latter a pioneering work in "cyclic form", was performed that year but published only much later after revision and extensive re-orchestration as Op. 120). He devoted 1842 to composing chamber music, including the [[Piano Quintet (Schumann)|Piano Quintet in E-flat]], Op. 44, now one of his best known and most admired works; the [[Piano Quartet (Schumann)|Piano Quartet]] and [[String Quartets (Schumann)|three string quartets]]. These two years are sometimes called Schumann's "Year of Symphonies" and "Year of Chamber Music" respectively. In 1843 he wrote ''[[Paradise and the Peri]]'', his first attempt at concerted vocal music, an [[oratorio]] style work based on ''[[Lalla-Rookh]]'' by [[Thomas Moore]]. The main role of Peri in the world premiere was performed by Schumann's family friend, soprano [[Livia Frege]].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Reich|first=Nancy B.|url=http://archive.org/details/claraschumannart00reic|title=Clara Schumann : the artist and the woman|date=1988|publisher=Ithaca : Cornell University Press|others=Internet Archive|isbn=978-0-8014-9388-1}}</ref> After this, his compositions were not confined to any one form during any particular period. |

|||

In addition to his chamber works for what were or were becoming standard combinations of instruments, Schumann wrote for some unusual ensembles and was often flexible about which instruments a work called for: in his [[Adagio and Allegro for Horn and Piano|Adagio and Allegro]], Op. 70 the pianist may, according to the composer, be joined by either a horn, a violin or a cello, and in the {{lang|de|Fantasiestücke}}, Op. 73 the pianist may be duetting with a clarinet, violin or cello.<ref name=grove/> His Andante and Variations (1843) for two pianos, two cellos and a horn (see sound clips, right) later became a piece for just the pianos.<ref name=grove/> |

|||

The stage in his life when he was deeply engaged in setting Goethe's ''[[Goethe's Faust|Faust]]'' to music (1844–53) was a turbulent one for his health. He spent the first half of 1844 with Clara on tour in Russia, and his depression grew worse as he felt inferior to Clara as a musician. On returning to Germany, he abandoned his editorial work and left Leipzig for [[Dresden]], where he had persistent "[[nervous prostration]]". As soon as he began to work, he was seized with fits of shivering and an apprehension of death, experiencing an abhorrence of high places, all metal instruments (even keys), and drugs. Schumann's diaries also state that he suffered perpetually from imagining that he had the [[A (musical note)#Designation by octave|note A5]] sounding in his ears.<ref name="Jensen 2001" /> |

|||

==Recordings== |

|||

His state of unease and [[neurasthenia]] is reflected in his [[Symphony No. 2 (Schumann)|Symphony in C]], numbered second but third in order of composition, in which the composer explores states of exhaustion, obsession, and depression, culminating in Beethovenian spiritual triumph. Also published in 1845 was his [[Piano Concerto (Schumann)|Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54]], originally conceived and performed as a one-movement ''Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra'' in 1841. It is one of the most popular and oft-recorded of all piano concertos; according to Hutcheson "Schumann achieved a masterly work and we inherited the finest piano concerto since Mozart and Beethoven".<ref name="Daverio" /> |

|||

All Schumann's major works and most of the minor ones have been recorded. From the 1920s his music has had a prominent place in the catalogues. In the 1920s [[Hans Pfitzner]] recorded the symphonies, and other early recordings were conducted by [[Georges Enescu]] and [[Arturo Toscanini]]. Large-scale performances with modern symphony orchestras have been recorded under conductors including [[Herbert von Karajan]], [[Wolfgang Sawallisch]] and [[Rafael Kubelik]], and from the mid-1990s smaller ensembles such as the [[Orchestre des Champs-Élysées]] with [[Philippe Herreweghe]] and the [[Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique]] with [[John Eliot Gardiner]] have recorded [[Historically informed performance|historically informed]] readings of Schumann's orchestral music. |

|||

The songs featured in the recorded repertoire from the early days of the gramophone, with performances by singers such as [[Elisabeth Schumann]] (no relation to the composer), [[Friedrich Schorr]], [[Alexander Kipnis]] and [[Richard Tauber]], followed in a later generation by [[Elisabeth Schwarzkopf]] and [[Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau]]. Although in 1955 the authors of ''The Record Guide'' lamented the prevailing scarcity of Schumann's songs on record,<ref>Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 687</ref> by the early twenty-first century every one of them was available on disc. A complete set was published in 2010 with the songs in chronological order of composition; [[Graham Johnson (musician)|Graham Johnson]] accompanied a range of singers including [[Ian Bostridge]], [[Simon Keenlyside]], [[Felicity Lott]], [[Christopher Maltman]], [[Ann Murray]] and [[Christine Schäfer]].<ref name=gj>Johnson, pp. 5–24</ref> Pianists for other recordings of Schumann Lieder have included [[Gerald Moore]], [[Dalton Baldwin]], [[Erik Werba]], [[Jörg Demus]], [[Geoffrey Parsons (pianist)| Geoffrey Parsons]], and more recently [[Roger Vignoles]], [[Irwin Gage]] and [[Ulrich Eisenlohr]].<ref>March ''et al'', pp. 1147–1149; and [https://www.naxosmusiclibrary.com/login "Robert Schumann"], Naxos Music Library. Retrieved 17 May 2024 {{subscription}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Robert u Clara Schumann 1847.jpg|thumb|left|Robert and Clara Schumann in 1847, lithograph with a personal dedication]] |

|||