Ali Pasha of Ioannina: Difference between revisions

ce |

|||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

The principal role of geography in the communal groups of his time were comprehended by Ali. He insisted that Ioannina, located in the Greek [[Epirus (region)|district of Epirus]], was Albanian. He also considered the Albanian population who lived in the area not as immigrants but as indigenous people of the region. He tried to justify his plans on the territories under foreign protectorate on the Ionian coast also by insisting that they were part of "Albania" as well.{{sfn|Fleming|2014|p=63}} |

The principal role of geography in the communal groups of his time were comprehended by Ali. He insisted that Ioannina, located in the Greek [[Epirus (region)|district of Epirus]], was Albanian. He also considered the Albanian population who lived in the area not as immigrants but as indigenous people of the region. He tried to justify his plans on the territories under foreign protectorate on the Ionian coast also by insisting that they were part of "Albania" as well.{{sfn|Fleming|2014|p=63}} |

||

Language was a major definiting element in Ali's identity, as well of his government and the region it controlled in general. Diplomatic business was exclusively conducted in Greek as well as much of the former correspondence. The formal bureaucratic language of the Ottoman Emire was entirely replaced with Greek in his pashalik.{{sfn|Fleming|2014|p=63}} |

|||

Ali's policy as ruler of Ioánnina was mostly governed by expediency; he operated as a semi-independent despot and pragmatically allied himself with whoever offered the most advantage at the time. In fact, it was Ali Pasha and his Albanian soldiers and mercenaries who subdued the independent [[Souli]].<ref>Sakellariou pp. 250–251</ref> |

Ali's policy as ruler of Ioánnina was mostly governed by expediency; he operated as a semi-independent despot and pragmatically allied himself with whoever offered the most advantage at the time. In fact, it was Ali Pasha and his Albanian soldiers and mercenaries who subdued the independent [[Souli]].<ref>Sakellariou pp. 250–251</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:53, 14 July 2023

Ali Pasha | |

|---|---|

| Ali Tepelena | |

Ali Pasha at the Lake of Butrint, by Louis Dupré | |

| Pasha of Yanina | |

| In office 1788–1822 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1740 Tepelena, Pashalik of Berat, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | January 24, 1822 (aged 81–82) Ioannina, Pashalik of Yanina, Ottoman Empire |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parent(s) | Veli Bey and Hanka |

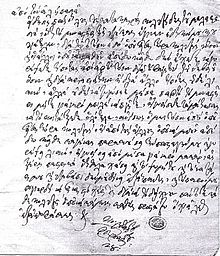

| Signature |  |

| Nickname(s) | "Aslan" (Turkish: Lion) "Lion of Yannina"[1] "Muslim Bonaparte"[1] |

Tepedelenli Ali Pasha or Ali Pasha of Tepelena (Albanian: Ali Tepelena; 1740 – 24 January 1822), commonly known as Ali Pasha of Ioannina, was an Albanian ruler who served as Ottoman pasha of the Pashalik of Yanina, a large part of western Rumelia, which under his rule acquired a high degree of autonomy and even managed to stay de facto independent. His court was in Tepelena and Ioannina,[2] and the territory he governed incorporated central and southern Albania, most of Epirus and the western parts of Thessaly and Greek Macedonia. Conceiving his territory in increasingly independent terms, Ali Pasha's correspondence and foreign Western correspondence frequently refer to the territories under Ali's control as Albania,[3] while his subject population was by vast majority Greek.[4] Ali had three sons: Muhtar Pasha, who served in the 1809 war against the Russians, Veli Pasha, who became Pasha of the Morea Eyalet and Salih Pasha, governor of Vlorë.[5][6]

Ali first appears in historical accounts as the leader of a band of brigands who became involved in many confrontations with Ottoman state officials in Albania and Epirus. He joined the administrative-military apparatus of the Ottoman Empire, holding various posts until 1788 when he was appointed pasha, ruler of the sanjak of Ioannina. His diplomatic and administrative skills, his interest in modernist ideas and concepts, his popular Muslim piety, his respect towards other religions, his suppression of banditry, his vengefulness and harshness in imposing law and order, and his looting practices towards persons and communities in order to increase his proceeds caused both the admiration and the criticism of his contemporaries, as well as an ongoing controversy among historians regarding his personality. As his influence grew, his involvement in Ottoman politics increased culminating in his active opposition to the ongoing Ottoman military reforms. After being declared a rebel in 1820, he was captured and killed in 1822 at the age of 81 or 82, after a successful military campaign against his forces. In Western literature, Ali Pasha became the personification of an "oriental despot".[1]

Name

Ali Pasha was variously referred to as of Tepelena, of Ioannina/Janina/Yannina or the Lion of Yannina. His native name was Albanian: Ali Tepelena, and he was referred to as Ali Pashë Tepelena or Ali Pasha i Janinës; and in other local languages as Aromanian: Ali Pãshelu; Greek: Αλή Πασάς Τεπελενλής Ali Pasas Tepelenlis or Αλή Πασάς των Ιωαννίνων Ali Pasas ton Ioanninon (Ali Pasha of Ioannina); and Turkish: Tepedelenli Ali Paşa (Ottoman Turkish: تپهدلنلي علي پاشا).[1]

Ancestry and early life

At some point in the 19th century, Ali's family was attributed with a legendary ancestry; according to this claim, Ali's family supposedly descended from a Mevlevi dervish named Nazif who migrated from Konya to Tepelene through Kütahya.[1][7] However, this tradition is unfounded, as Ali's family was of local Albanian origin.[1][8][9] They had achieved some stature by the 17th century.[1]

Ali's grandfather Muhtar Bey and great-grandfather were both bandit chieftains.[1] Muhtar had died during the 1716 siege of Corfu.[1] Ali's father, Veli Bey, was a local ruler of Tepelena.[10]

Ali himself was born in Tepelena or in the adjacent village of Beçisht.[7][10] According to George Bowen, Ali Pasha was part of the Lab tribe; as this tribe was in disrepute among the other Albanians for their poverty and predatory habits, he thought it proper to call himself after Tepelena, a town of the Tosks; no one dared to dispute this until after his death.[11] Ali's father Veli Bey was involved in a rivalry with his father's cousin Islam Bey, who was also a local ruler.[1] Islam Bey was appointed mutasarrıf of Delvinë in 1752, but Ali's father managed to kill him and was allowed to succeed his cousin as mutasarrıf in 1762.[1] However, his father was assassinated shortly after (when Ali was nine or ten), and he was brought up by his mother, Chamko (or Hanko), who originally hailed from Konitsa.[7][1]

Early years

In Ali's early years, he distinguished himself as a bandit.[10] He affiliated himself with the Bektashi sect.[10] The family lost much of its political and material status following the murder of his father. In 1758, his mother, Hanko, reportedly a woman of extraordinary character, thereupon herself formed and led a brigand band, and studied to inspire the boy with her own fierce and indomitable temper, with a view to revenge and the recovery of their lost wealth.[13] According to Byron: "Ali inherited 6 dram and a musket after the death of his father. Ali collected a few followers from among the retainers of his father, made himself master, first of one village, then of another, amassed money, increased his power, and at last found himself at the head of a considerable body of Albanians".[citation needed] Ali became a famous brigand leader and attracted the attention of the Ottoman authorities. He was assigned to suppress brigandage and fought for the "Sultan and Empire" with great bravery, particularly against the famous rebel Pazvantoğlu. He aided the Pasha of Negroponte in putting down a rebellion at Shkodër, it was during this period that he was introduced to the Janissary units and was inspired by their discipline. In 1768 he married the daughter of the wealthy Pasha of Delvina, with whom he entered into an alliance.[citation needed]

Ali was appointed mutasarrif of Ioanninna at the end of 1784 or beginning of 1785, but was soon dismissed, returning to the position at the end of 1787 or start of 1788.[14] His rise through Ottoman ranks continued with his appointment as lieutenant to the Pasha of Rumelia.

After supporting the Sultan in conflicts between local feudal lords, he was appointed to rule the Sanjak of Delvina in 1785 with the title of Pasha. In reward for his services at Banat during the Austro-Turkish War (1787–1791), he was additionally granted the Sanjak of Trikala in 1787, which was at the time suffering from brigand raids. After achieving peace in Trikala by hunting down brigands, he was granted the role of supervisor of the tolls of "Tosceria and Epirus". In 1787 or 1788 he seized control of town of Ioannina, the major financial centre of all of Epirus and Albania, and enlisted most of the brigands under his own banner. That same year, Ali declared himself ruler of the Sanjak of Ioannina under the title Pasha of Yanina, delegating the title of Pasha of Trikala to his son, Veli.[15] This marked the beginning of the Pashalik of Yanina, and Ioannina would be his power base for the next 33 years. Over this period, Ali took advantage of a weak Ottoman government to expand his territory still further until he gained control over most of Albania and northwestern Greece.[citation needed]

During war-time, Ali Pasha could assemble an army of 50,000 men in a matter of two to three days and could double that number in two to three weeks. Leading these armed forces was the Supreme Council.[16] The Commander-in-chief was the founder and financier, Ali Pasha. Council members included Muftar Pasha, Veli Pasha, Celâleddin Bey, Abdullah Pashe Taushani[citation needed] and a number of his trusted men like Hasan Dervishi, Omar Vrioni, Meço Bono, Ago Myhyrdari, Thanasis Vagias, Veli Gega and Tahir Abazi.[16][17]

Ali Pasha as ruler

As Pasha of Ioannina, he slowly laid the foundations for the creation of an almost independent state, which included a large part of Greece and Albania. During his rule, the town of Ioannina developed into a major educational, cultural, political and economic hub. In order to achieve his goals, he allied with all religious and ethnic groups in his territory. At the same time, he did not hesitate to fiercely crush any opponent. As he also developed relations with European powers.[18] By the time of his accession to the Pashalik of Yanina, several almost-independent Albanian and Greek towns of the region reversed their approach of ostility against the Ottoman rule and pledged their loyalty to Ali.[19]

In the latter half of the 18th century, during his administration, Ali Pasha replaced Greek armatoles from the territories under his control, making the regions armatoles almost exclusively Albanian. The thus deposited Greek armatoles became klephts and their subsequent anti-armatoloi activity was not only brigandage, but also a form of resistance against Ottoman rule.[20]

The principal role of geography in the communal groups of his time were comprehended by Ali. He insisted that Ioannina, located in the Greek district of Epirus, was Albanian. He also considered the Albanian population who lived in the area not as immigrants but as indigenous people of the region. He tried to justify his plans on the territories under foreign protectorate on the Ionian coast also by insisting that they were part of "Albania" as well.[25]

Language was a major definiting element in Ali's identity, as well of his government and the region it controlled in general. Diplomatic business was exclusively conducted in Greek as well as much of the former correspondence. The formal bureaucratic language of the Ottoman Emire was entirely replaced with Greek in his pashalik.[25]

Ali's policy as ruler of Ioánnina was mostly governed by expediency; he operated as a semi-independent despot and pragmatically allied himself with whoever offered the most advantage at the time. In fact, it was Ali Pasha and his Albanian soldiers and mercenaries who subdued the independent Souli.[26]

Ali Pasha wanted to establish in the Mediterranean a sea-power which would be a counterpart of that of the Dey of Algiers, Ahmed ben Ali.[13] In order to gain a seaport on the Albanian coast, which was dominated by Venice, Ali Pasha formed an alliance with Napoleon I of France, who had established François Pouqueville as his general consul in Ioannina, with the complete consent of the Ottoman Sultan Selim III. British traveler Henry Holland reported in 1815 that during a personal conversation with Ali it apparently emerged that Napoleon, at a certain point, had promised Ali the position of King of Albania, but Holland also remarked that Ali was not convinced by the offer, because he distrusted the French.[27]

After the Treaty of Tilsit, where Napoleon granted[clarification needed] the Czar his plan to dismantle the Ottoman Empire, Ali Pasha switched sides and allied with Britain in 1807; a detailed account of his alliance with the British was written by Sir Richard Church. His actions were permitted by the Ottoman government in Constantinople. Ali Pasha was very cautious and displeased by the emergence of the new Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II in the year 1808.

Lord Byron together with John Cam Hobhouse visited Ali's court in Tepelena and Ioannina in 1809.[28] Byron recorded the encounter in his work Childe Harold. They travelled to Albania to see the country that was, until then, mostly unknown in Britain. Byron presented Albanians as a free people who lived in their state under their leader, Ali Pasha, described by Byron as a "man of first abilities who governs the whole of Albania".[29]

In a letter to his mother, Byron deplored Ali's cruelty: [30]

"His Highness is a remorseless tyrant, guilty of the most horrible cruelties, very brave, so good a general that they call him the Mahometan Buonaparte ... but as barbarous as he is successful, roasting rebels, etc, etc.."

Charles Robert Cockerell visited Albania and met Ali Pasha in 1814. Admiring Ali Pasha's governance, Cockerell explained: [31]

"There is law — for everyone admits his impartiality as compared with that of rulers in other parts of Turkey — and there is commerce. He [Ali Pasha] has made roads, fortified the borders, put down brigandage, and raised Albania into a power of some importance in Europe."

Different tales about his sexual proclivities emerged from western visitors to Pasha's court (including Lord Byron, the Baron de Vaudoncourt [fr],[32] and Frederick North, Earl of Guildford). These documenters wrote that he kept a large harem of both women and men. Such accounts may reflect the Orientalist imagination of Europe and underplay the historical role of Pasha rather than telling us anything concrete about his sexuality.[33]

Ali Pasha, according to one opinion, "was a cruel and faithless tyrant; still, he was not a Turk, but an Albanian; he was a rebel against the Sultan (Mahmud II), and he was so far an indirect friend of the Sultan's enemies".[34] Throughout his rule he is known to have maintained close relations and corresponded with famous leaders such as Husein Gradaščević, Ibrahim Bushati, Mehmet Ali Pasha and Ibrahim Pasha.[citation needed]

Though certainly no friend to the Greek Nationalists (he had personally ordered the painful execution of the Klepht Katsantonis), his rule brought relative stability. It was only after his forceful deposition that the people of Greece objected to the rule of the Sultan Mahmud II and the newly appointed Hursid Pasha and thus began the Greek War of Independence.

A long epic poem known as the Alipashiad consisting of more than 10,000 lines is dedicated to the exploits of Ali Pasha. The Alipashiad was composed by Haxhi Shekreti, an Albanian Muslim from Delvina and was written entirely in Greek.[35]

Impact on modern Greek Enlightenment

Although Ali Pasha's native language was Albanian he used[when?] Greek for all his courtly dealings,[36] with the effect of linking, although inchoately, the ruling class with the predominantly Greek-speaking population of the territories where Ali's rule stretched.[37] As a consequence, a part of the local Greek population showed sympathy towards his rule.[36] This also activated new educational opportunities, with businessmen of the Greek diaspora, subsidizing a number of new educational purposes.[37]

Education in Ioannina and its school became renowned throughout the Greek world. Those shools were operating by prestigious staff among them philologist Athanasios Psalidas, major contributor to the modern Greek Enlightenment and Georgios Sakellarios. Ioannis Kolettis served as Ali's son Muchtar personal physician and composed several scientific works. As such academic elite emerged which also included members of Ali's court. Many of these personalities took later prominent roles in the Greek War of Independence.[38]

Atrocities

In 1808, Mühürdar, a commanding Janissary of Ali Pasha, captured one of his most renowned opponents, the Greek klepht Katsantonis, who was executed in public by having his bones broken with a sledgehammer.[39] One of Ali's most notorious crimes, without a legal indictment, was the mass murder of 17 or 18 chosen young Greek girls of Ioannina. They were, without a trial, sentenced as adulteresses, tied up in sacks and drowned in Lake Pamvotis.[40] Oral Aromanian tradition (songs) tells about the cruelty of Ali Pasha's troops.[citation needed]

In October 1798 Ali's troops attacked the coastal town of Preveza, which was defended by a small garrison of French and local Greeks. When the town was finally conquered, a major slaughter occurred against the local people as retaliation for their resistance.[41] He also tortured the French and Greek prisoners of war before their execution. A French officer described the atrocities ordered by Ali Pasha and his cruel character:

The chamber where Mr. Tissot had been locked was facing to the place with the bloody remainders of the French and Greeks killed in Preveza. The officer witnessed the cruel death of several Prevezans whom Ali sacrificed to his rage, and the behavior of the Pasha during executions: one hundred times more cruel than Nero, Ali was viewing with sarcasm the torments of his victims. His bloody soul enjoyed with execrable pleasure his indescribable vengeance, and meditated still more atrocities.

Every French captive was given a razor with which he was forced to skin the severed heads of his compatriots. Those who refused were beaten on the head with clubs. After the heads were skinned, the masks were salted and put in cloth bags. When the operation was finished, the French were driven back into the hangar, and they were warned to prepare for death.

Soon after they brought the unfortunate Prevezans, whose hands had been tied behind their back by the Albanians. They piled them in large boats and drove to Salagora (a small island in the Gulf of Arta), where a legion of executioners was waiting. Ali made a hecatomb of these four hundred unfortunates. Their heads were carried in triumph and then offered in Ioannina, a spectacle worthy of his ferocity.[42]

In the early nineteenth century his troops completed the destruction of the once-prosperous cultural center of Moscopole, in modern southeastern Albania, and forced its Aromanian population to flee from the region.[43] Many Aromanians scattered throughout the Balkans, founding settlements such as Kruševo, but also left the region and went to other countries, forming an Aromanian diaspora.[44] As a result, hundreds or even thousands of Aromanian families had to flee from their native settlements and find refugee in regions outside of Ali's control.[45] The same campaign of persecution was launched towards Sarakatsani communities.[45]

Downfall

In 1819, Ottoman diplomat Halet Efendi brought the attention of Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839) issues conspicuously related to Ali Pasha. Efendi accused Ali Pasha of grabbing power and influence in Ottoman Rumelia away from the Sublime Porte. In 1820, Ali Pasha, after long tensions with the Turkish Reforms, allegedly ordered the assassination of Gaskho Bey, a political opponent in Constantinople; Sultan Mahmud II, who sought to restore the authority of the Sublime Porte, took this as a major opportunity to move against Ali Pasha by ordering his immediate deposition.

Ali Pasha refused to resign his official post and put up a fierce resistance to the Sultan's troop movements as some 20,000 Turkish troops led by Hursid Pasha were fighting Ali Pasha's small but formidable army. Most of his followers abandoned him without fighting and fled, including Androutsos and his sons Veli and Muhtar, or else joined the Ottoman army. Among these were Omer Vrioni and Alexis Noutsos, who went unopposed to Ioannina, which was besieged in September 1820.

On 4 December 1820, Ali Pasha and the Souliotes formed an anti-Ottoman coalition, to which the Souliotes contributed 3,000 soldiers. Ali Pasha gained the support of the Souliotes mainly because he offered to allow the return of the Souliotes to their land, and partly by appeal to their perceived Albanian origin.[46][47] Initially, the coalition was successful and managed to control most of the region, but when the Muslim Albanian troops of Ali Pasha were informed of the beginning of the Greek revolts in the Morea, it was terminated.[48]

Ali's rebellion against the Sublime Porte increased the value of the Greek military element since their services were sought by the Porte as well. He is said to have contracted the services of the Klephts and Souliots in exile in the Ionian Islands as well as the armatoles under his command.[49] However he feared that the Klephts might rout him before the arrival of the Ottoman Turks.

His separatist actions constitute a great example of the institutional corruption and dividing trends prevailing in the Ottoman Empire at the time. His effort to become an independent ruler finally caused the reaction of the Sublime Porte, which sent an army lead by Hurshid Pasha against him in March 1821, which surrounded him in Ioannina.[50] By the end of 1821 after about two years of fighting, with most of his men having deserted him Ali retreated with Kyra Vassiliki and 70 guards to the citadel in the north eastern corner of Ioannina Castle.[51] He had his men place barrels of gunpowder in the basement should it become necessary to blow up the citadel. Ali Pasha accepted a request from the Ottomans to enter into negotiations, in which he demanded that he be allowed to see the Sultan in person. Hurshid Pasha promised to pass on his request to the Sultan and in the interim issued Ali with a safe pass signed by himself and the other pasha’s in the army. Hurshid Pasha also sent Ali a fake imperial firman (decree), instructing him to leave the citadel while his request for a full pardon was considered.[51]

Death

Despite a feeling that he was being deceived Ali agreed to a truce and left the citadel with his wife, entourage and bodyguards and settled in the Monastery of St Panteleimon on the island in Lake Pamvotis, previously taken by the Ottoman army during the siege. A few weeks later he was visited by a group of pashas and senior officials. He suspected a trap but the meeting passed without incident. A few days later on 24 January 1822[50] the Ottoman’s boats returned from which a senior official called Kiose Mehmed Pasha, disembarked, claiming that he had in his possession the Sultan’s firman for his execution. Ali told him to stay back until he had read the document, but the pasha ignored him and called for him to comply.[51] Ali pulled out his pistol and fired at him, the Pasha returned fire while Kaftan Agas, Hurshid’s chief of his staff, managed to wound Ali in the arm with his sword.[50] Ali’s bodyguards rushed to protect him and managed to pull him into the building. The resulting gunfight only ending when Ali was mortally wounded in the abdomen by a bullet.[50] This caused his men to surrender. Ali was then beheaded. His last request to his chief bodyguard Thanasis Vagias was for his wife Kyra to be killed in order to prevent her falling into the hands of his enemies, but this was ignored.[50]

Hurshid Pasha, to whom it was presented on a large dish of silver plate, rose to receive it, bowed three times before it, and respectfully kissed the beard, expressing aloud his wish that he himself might deserve a similar end. To such an extent did the admiration with which Ali's bravery inspired these men to efface the memory of his crimes.[citation needed]

Ali’s head was wrapped in a cloth, put on a silver platter and displayed though the streets and the homes of the notables of Ioannina to prove that the Ali was dead. The local archbishop was having dinner with friends when Hurshid’s bodyguards forced their way into the room and desposited the head on the dinner table and demanded money. After saying a prayer for Ali, the archbishop handed over a bag of gold coins. Ali Pasha’s headless corpse was buried with full honors in a mausoleum next to the Fethiye Mosque, which he shares with one of his wives. Despite his brutal rule, villagers paid their last respect to Ali: "Never was seen greater mourning than that of the warlike Epirotes."[citation needed] The head was meanwhile sent to Constantinople where was displayed to the public on a revolving platter in a courtyard of the Sultan’s palace. When the Sultan subsequently had Ali’s three sons and grandson executed, Ali’s head was buried with them in tombs outside the Selvyria gate in Constantinople.[51]

The former monastery in which Ali Pasha was killed is today a popular tourist attraction. The holes made by the bullets can still be seen, and the monastery has dedicated to him a museum, which includes a number of his personal possessions.[52]

Religion

Ali Pasha was born into a Bektashi Muslim family.[53] Regardless, the struggle for power and the political turmoils within the empire required for him to support non-Muslim or heterodox priests, beliefs, and orders,[54] and especially the Orthodox Christian population which formed the majority of the population in the region he ruled.[55] One of the spiritual figures which influenced him was Saint Cosmas. Ali ordered and supervised the construction of a monastery dedicated to him near Berat.[54][56] Ali Pasha maintained control over the Christian population but respected the monasteries and stayed on good terms with the upper clergy.[57]

He strongly supported the Sufi orders, well-spread in Rumelia at the time. Ali was close to the dominant Sufi orders as the Naqshbandi, Halveti, Sâdîyye, or even Alevi.[54] Specifically the famous Sufi shrines in Yanina and Parga were Naqshbandi.[58] The order that was mostly supported by him was the Bektashis and he is accepted today to have been a Bektashi follower, initiated by Baba Shemin of Fushë-Krujë.[59] Through his patronage, Bektashism spread in Thessaly, Epirus, South Albania, and in Kruja.[58][60][61][62][63] Ali's tomb headstone was capped by the crown (taj) of the Bektashi order.[64] Nasibi Tahir Babai, a Bektashi saint, is regarded as one of three spiritual advisers of Ali Pasha.[65]

Ali Pasha in literature

According to the Encyclopedia of Islam, in Western literature, Ali Pasha became the personification of an "oriental despot".[1]

In the early 19th century, Ali's personal balladeer, Haxhi Shekreti,[66] composed the poem Alipashiad. The poem was written in Greek language, since the author considered it a more prestigious language in which to praise his master.[67] Alipashiad bears the unusual feature of being written from the Muslim point of view of that time.[68] He is the title character of the 1828 German singspiel Ali Pascha von Janina by Albert Lortzing.

In the novel The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, père, Ali Pasha's downfall is revealed to have been brought about by French Army officer Fernand Mondego. Unaware of Mondego's collusion with the Sultan's forces, Pasha is described as having entrusted his wife, Kyra Vassiliki, and daughter, Haydée, to Mondego, who sells them into slavery. Mondego then personally murders Ali Pasha and returns to France with a fortune. The novel's protagonist, Edmond Dantés, subsequently locates Haydée, buys her freedom, and helps her avenge her parents by testifying at Mondego's court martial in Paris. Mondego, who is found guilty of "felony, treason, and dishonor", is abandoned by his wife and son and later commits suicide.

Alexandre Dumas, père wrote a history, Ali Pacha, part of his eight-volume series Celebrated Crimes (1839–40).

Ali Pasha is also a major character in the 1854 Mór Jókai's Hungarian novel Janicsárok végnapjai ("The Last Days of the Janissaries"), translated into English by R. Nisbet Bain, 1897, under the title The Lion of Janina.

Ali Pasha and Hursid Pasha are the main characters in Ismail Kadare's historic novel The Traitor's Niche (original title Kamarja e turpit).

Ali Pasha provokes the bey Mustapha (a fictional character) in Patrick O'Brian's 1981 The Ionian Mission to come out fighting on his own account, when the British navy is in the area seeking an ally to push the French off Corfu. The Turkish expert for the British Navy visits him to learn this tangled story, which puts Captain Aubrey out to sea to take Mustapha in battle.

Many of the conflicting versions about the origin of the "Spoonmaker's Diamond", a major treasure of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, link it with Ali Pasha – though their historical authenticity is doubtful. [citation needed]

Loretta Chase's 1992 historical romance novel The Lion's Daughter includes Ali Pasha and a possible revolt against him by a cousin, Ismal.

The best selling graphic novel Sons of Chaos written by Chris Jaymes published in the US by Penguin Random House in 2019 and in Greece by Kaktos Publishing in 2021 surrounds the story of Ali Pasha and his relationship with the Suliotes.[69][70]

Legacy

Ali Pasha is regarded by Albanian nationalists as a national hero who rose against Ottoman rule.[71] Although Ali Pasha's intent was not to build a nation state, the legacy left behind by him was utilized by the Albanian elite to construct their nationalist platform. After Ali Pasha's death the base of Albanian nationalist activities and uprisings against the Ottoman Empire became northern Albania and Kosovo.[72]

See also

- Albania under the Ottoman Empire

- Dimitrios Deligeorgis, a secretary to Ali Pasha

- Greek War of Independence

- History of Albania

- History of Ottoman Albania

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Clayer 2014.

- ^ Tanner 2014, p. 21: "That the word 'Albania' was known at all to the English-speaking public in the early nineteenth century was largely down to Byron, who passed through on his first expedition to Greece, aged 21. After reaching Patras in September 1809, he made a detour lasting several weeks to Ioannina, which now lies in Greece but was then considered the de facto capital of south-ern Albania, the honour normally being accorded to Shkodra in the north. He also visited Tepelena, which, alongside Ioannina, was the headquarters of the notorious warlord, Ali Pasha. He then returned to Patras and continued to Athens."

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 116.

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 157.

- ^ "TEPEDELENLİ ALİ PAŞA'NIN OGULLARI" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Sellheim, R. (1992). Oriens. BRILL. p. 303. ISBN 978-90-04-09651-6. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c H. T. Norris (1993). Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 231–. ISBN 978-1-85065-167-3.

- ^ Fleming (1999): p. 60.

- ^ Ahmet Uzun. Ο Αλή Πασάς ο Τεπελενλής και η περιουσία του.. [Ali Pasha from Tepeleni and his fortune] (Greek), p. 3: "Εξαιτίας της μοναδικότητας του ονόματος μιας οικογένειας που μετανάστευσε από την Ανατολία στη Ρούμελη και εγκαταστάθηκε στο Τεπελένι, υπάρχουν ισχυρισμοί που τον θέλουν Τούρκο. Εντούτοις οι ισχυρισμοί αυτοί είναι αβάσιμοι αφού στην πραγματικότητα είναι αποδεδειγμένο ότι καταγόταν από τη νότια Αλβανία." [Because of the uniqueness of the name of a family which emigrated from Anatolia to Rumelia and settled in Qendër Tepelenë, there are claims that he was a Turk. However, these claims are unfounded since, in reality, it is proven that he came from southern Albania.]

- ^ a b c d Robert Elsie (December 24, 2012). A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History. I. B. Tauris. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3.

- ^ George Bowen (1852), Mount Athos, Thessaly and Epirus: A diary of a Journey, Francis & John Rivington, London, p. 192, cited in Hart Laurie Kain (1999)Culture, civilization and demarcation at the northwest borders of Greece, American Ethnologist, 26(1), pp. 196–220, footnote 19.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (ed.). "1813 Thomas Smart Hughes: Travels in Albania". albanianhistory.net.

- ^ a b Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 659–661.

- ^ Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. p. 364. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- ^ Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Earthlab. p. 337. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- ^ a b Historia e Popullit Shqipetar. Tirana, Albania: Shtepia Botuese Toena. 2002.

- ^ Universiteti Shtetëror i Tiranës; Instituti i Historisë (1987). "Studime Historike". 41: 140. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Findley, Carter V. (2012). Modern Türkiye Tarihi İslam, Milliyetçilik ve Modernlik 1789-2007. İstanbul: Timaş Yayınları. p. 30. ISBN 978-605-114-693-5.

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 171.

- ^ Fleming, K.E. (2021). "Armatoloi". In Speake, Graham (ed.). Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition. Routledge. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-1-135-94206-9.

- ^ "Janina, Albania (subsequently Greece): the audience chamber of Ali Pasha. Colour lithograph after G.D. Beresford, 1855". ARTSTOR. JSTOR 24792656.

- ^ de la Poer Beresford, George (1855). Twelve Sketches in Double-tinted Lithography of Scenes in Southern Albania. London: Day and Son.

- ^ Hernandez, David R. (2019). "The Abandonment of Butrint: From Venetian Enclave to Ottoman Backwater". Hesperia. 88: 365–419. p. 408: "George de la Poer Beresford published 12 double-tinted lithographs of scenes from southern Albania in 1855.214"

- ^ Prokopiu, Geōrgios A. (2019). Archontika tēs Kozanēs: architektonikē kai Xyloglypta (PDF). Athens: Benaki Museum. p. 13. ISBN 978-960-476-261-3.

Εικ. 11. Η αίθουσα των ακροάσεων του Αλή-Πασά στα Γιάννενα (περί το 1800).

- ^ a b Fleming 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Sakellariou pp. 250–251

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 88.

- ^ Lord Byron's Correspondence; John Murray, editor.

- ^ Dauti 2018, pp. 29–30, 35.

- ^ Rowland E. Prothero, ed., The Works of Lord Byron: Letters and Journals, Vol. 1, 1898, "mahometan+buonaparte"&pg=PA252 p. 252 (letter dated Prevesa, 12 November 1809)

- ^ Dauti 2018, p. 37.

- ^ Vaudoncourt, Guillaume de Memoirs on the Ionian Islands ... : including the life and character of Ali Pasha. London: Baldwin, Cradock and Joy, 1816

- ^ Murray, Stephen O. & Roscoe, Will (1997) Islamic Homosexualities: culture, history, and literature, NYU Press, p. 189

- ^ The Ottoman Power in Europe by Edward Augustus Freeman

- ^ Wace A.J.B. and Thompson M. S. (1914) The nomads of the Balkans: An account of life and customs among the Vlachs of Northern Pindus, Methuen & Co., Ltd., p. 192.

- ^ a b Fleming (1999): p. 63

- ^ a b Fleming (1999): p. 64: "The population of Ali's territories was predominantly Greek speaking, and the use of its common tongue by the ruling class had the effect of linking them, albeit inchoately, with that ruling class."

- ^ Fleming (1999): p. 65

- ^ Merry, Bruce. Encyclopedia of Modern Greek Literature. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004. ISBN 978-0-313-30813-0, p. 231.

- ^ Fleming (1999): p. 168.

- ^ Fleming (1999): p. 99.

- ^ "Précis des opérations générales de la division française du Levant: chargée ..." Magimel. January 6, 1805 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Winnifrith, Tom. Vlachs: the history of a Balkan people. Duckworth, 1987, ISBN 978-0-7156-2135-6, p. 130.

- ^ Zeana, Corneliu (2021). Boldea, Iulian (ed.). "The Aromanians, a distinct Balkan ethnicity" (PDF). The Shades of Globalisation. Identity and Dialogue in an Intercultural World (in Romanian). Arhipelag XXI Publishing House: 39–44. ISBN 978-606-93691-3-5.

- ^ a b Kaser, Karl (1992). Hirten, Kämpfer, Stammeshelden: Ursprünge und Gegenwart des balkanischen Patriarchats (in German). Böhlau Verlag Wien. p. 368. ISBN 978-3-205-05545-7.

Die Herrschaft des Ali Pasa ... Hunderte oder far Tausende von Vlachen- und Sarakatsanenfamilien fluchteten in entfernte Gebiete, um ihre Freiheit zu retten.

- ^ Fleming, Katherine Elizabeth (1999). The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Katherine Elizabeth (1999). The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Victor Roudometof; Roland Robertson (2001), Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 25, ISBN 978-0-313-31949-5

- ^ John S. Koliopoulos Brigands with a Cause, p. 40

- ^ a b c d e "Pre-Revolution". Paul Vrellis Greek History Museum. 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Mazower, Mark (2021). The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (Hardback). Allen Lane. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-0-241-00410-4.

- ^ Νήσος Ιωαννίνων. (2009). Μουσεία (in Greek). Archived from the original on November 3, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ K. E. Fleming (1999), The Muslim Bonaparte: Diplomacy and Orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece, Princeton University Press, p. 32, ISBN 9780691001944, OCLC 39539333,

Sources agree he was born into an aristocratic Muslim Albanian family in the Albanian village of Tebelen

- ^ a b c Pierre Savard, Brunello Vigezzi (Commission of History of International Relations) (1999), Le Multiculturalisme Et L'histoire Des Relations Internationales Du XVIIIe Siècle À Nos Jours, Milano: Edizioni Unicopli, p. 68, ISBN 9788840005355, OCLC 43280624,

Tepedelenli Ali Pasa, governor of Yanya (Yannina) who was an Alevi-Bektashi and who also had great love for the Saint.

- ^ Fleming (1992): 66

- ^ Geōrgios K. Giakoumēs; Grēgorēs Vlassas; D. A. Hardy (1996), Monuments of Orthodoxy in Albania, Athens: Doukas School, p. 68, ISBN 9789607203090, OCLC 41487098,

KOLIKONTASI Monastery....thirty-four years after his tragic end, on the orders of 'his highness the Vizier Ali Pasha from Tepeleni'

- ^ Konstantinos, Giakoumis (2002). The monasteries of Jorgucat and Vanishte in Dropull and of Spelaio in Lunxheri as monuments and institutions during the Ottoman period in Albania (16th–19th centuries) (Doctor of Philosophy). University of Birmingham. p. 49. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

Ali Pasha dealt... Pasha of Ioannina

- ^ a b Natalie Clayer (2002), "III", in Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers; Bernd Jürgen Fischer (eds.), Albanian Identities: Myth and History, Indiana University Press, p. 130, ISBN 9780253341891, OCLC 49663291,

...he seemed to have been closer to the Sadiyye, the Halvetiyye or even the Nakshibendiyye (the tekke of Parga was Nakshibendi, as well as a well-kbown tekke of Ioannina)....

Ali Pasha was considered to be 'responsible for the propagation of Bektashism' in Thessaly, in South Albania and in Kruja... - ^ Miranda Vickers (1999), The Albanians: A Modern History, London: I.B. Tauris, p. 22, ISBN 9781441645005,

Around that time, Ali was converted to Bektashism by Baba Shemin of Kruja...

- ^ Robert Elsie (2004), Historical Dictionary of Albania, European historical dictionaries, Scarecrow Press, p. 40, ISBN 9780810848726, OCLC 52347600,

Most of the Southern Albania and Epirus converted to Bektashism, initially under the influence of Ali Pasha Tepelena, "the Lion of Janina", who was himself a follower of the order.

- ^ Vassilis Nitsiakos (2010), On the Border: Transborder Mobility, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries along the Albanian-Greek Frontier (Balkan Border Crossings- Contributions to Balkan Ethnography), Balkan border crossings, Berlin: Lit, p. 216, ISBN 9783643107930, OCLC 705271971,

Bektashism was widespread during the reign of Ali Pasha, a Bektashi himself,...

- ^ Gerlachlus Duijzings (2010), Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 82, ISBN 9780231120982, OCLC 43513230,

The most illustrious among them was Ali Pasha (1740–1822), who exploited the organisation and religious doctrine...

- ^ Stavro Skendi (1980), Balkan Cultural Studies, East European monographs, Boulder, p. 161, ISBN 9780914710660, OCLC 7058414,

The great expandion of Bektashism in southern Albania took place during the time of Ali Pasha Tepelena, who is believed to have been a Bektashi himself

- ^ H.T.Norris (2006), Popular Sufism in Eastern Europe: Sufi Brotherhoods and the Dialogue with Christianity and 'Heterodoxy', Routledge Sufi series, Routledge, p. 79, ISBN 9780203961223, OCLC 85481562,

...and the tomb of Ali himself. Its headstone was capped by the crown (taj) of the Bektashi order.

- ^ H.T.Norris (1993), Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World, University of South Carolina Press, pp. 73, 76, 162, ISBN 9780872499775, OCLC 28067651

- ^ Ruches, Pyrrhus J., ed. (1967). Albanian Historical Folksongs, 1716–1943: a survey of oral epic poetry from southern Albania, with original texts. Chicago: Argonaut. p. 123.

- ^ Tziovas, Dēmētrēs (2003). Greece and the Balkans: identities, perceptions and cultural encounters since the Enlightenment. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7546-0998-8.

- ^ Merry, Bruce (2004). Encyclopedia of modern Greek literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-313-30813-0.

- ^ "Sons of Chaos".

- ^ "Review: SONS OF CHAOS is an Epic Tale of Revolution". August 4, 2019.

- ^ Yaycioglu 2016, p. 112.

- ^ Dauti 2018, p. 62.

Sources

- "Ali Pasa Tepelenë." Encyclopædia Britannica (2005)

- "Ali Pasha (1744? – 1822)". The Columbia Encyclopedia (2004).

- Clayer, Nathalie (2014). "Ali Paşa Tepedelenli". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23950. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Ellingham et al. Rough Guide to Greece, (2000)

- Fleming, Katherine Elizabeth. The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4.

- Fleming, K. E. (2014). The Muslim Bonaparte: Diplomacy and Orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6497-3.

- Koliopoulos, John S. (1987) Brigands with a Cause, Brigandage and Irredentism in Modern Greece 1821–1912. Clarendon Press, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-822863-5

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus: 4000 Years of Greek History and Civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. ISBN 960-213-371-6.

- S. Aravantinos, Istoria Ali Pasa tou Tepelenli, [the history of Ali Pasha Tepelenli based on the unpublished texts by Panagiotis Arantinos] Athens 1895, (photographic reprint, Athens 1979).

- Gr. Lars, I Albania kai I Epiros sta teli tou IG’ kai stis arches tou IH’ aion. Ta Dytikovalkanika Pasalikia tis Othomanikis Autokratorias [Albania and Epirus I the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Ottoman Eyalets of Western Balkans, transl. A. Dialla, publ. Gutenberg, Athens 1994, pp. 144–173.

- G. Siorokas, I eksoteriki politiki tou Ali pasa ton Ioanninon. Apo to Tilsit sti Vienni [the internal affairs policy of Ali Pasha. From Tilsit to Vienna] (1807–1815), Ioannina, 1999.

- Skiotis, Dennis N., "From Bandit to Pasha: first steps in the rise to power of Ali of Tepelen, 1750–1784", International Journal of Middle East Studies 2: 3: 219–244 (July 1971) (JSTOR)

- Dauti, Daut (January 30, 2018). Britain, the Albanian Question and the Demise of the Ottoman Empire 1876-1914 (phd). University of Leeds.

- Tanner, Marcus (2014). Albania's mountain queen: Edith Durham and the Balkans. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781780768199.

- Dim. A. Zotos, I dikaiosyni eis to kratos tou Ali pasa [Justice in the state of Ali Pasha], Athens, 1938.

- Vaso D. Psimouli, Souli kai Souliotes, Athens 1998

- Ali Pasha Archives, 2007, I. Chotzi collection, Gennadius Library, Ed. – Cpmmentary – Index: V. Panagiotopoulos with collaboration of D. Dimitropoulou, P. Michailari, Vol. 4

- A. Papastavros, Ali Pasas, apo listarchos igemonas [Ali Pasha, from bandit to leader], publ. Apeirotan, 2013.

- W. M. Leake, Travels in northern Greece, Α.Μ.Ηakkert-Publisher, (photographic reprint Amsterdam 1967). Vol. 1, pp. 295,Vol. 4, pp. 260

- I. Lampridis, “Malakasiaka”, Epirotika Meletimata [Epirote Studies] 5 (1888), publ. 2. Society for Epirote Studies. (EHM), Ioannina 1993, p. 25

- Ali Pasha Archives, I. Chotzi collection, Gennadius Library, Ed. – Commentary – Index: V. Panagiotopoulos with the collaboration of D. Dimitropoulou, P. Michailari, 2007, Vol. B’, pp. 672–674 (doc. 851), 676–677, (doc. 855), 806-807 (doc. 943).

- G. Plataris, Kodikas Choras Metsovou ton eton 1708–1907 [Chora Metsovou Log of the years 1708–1907], Athens 1982, pp. 105, 120.

- V. Skafidas, “Istoria tou Metsovou” [History of Metsovo], Epirotiki Estia 11/121, 122 (1962), p. 387.

- M. Tritos, “Ta sozomena firmania ton pronomion tou Metsovou” [The surviving firmans about the privileges granted to Metsovo], Minutes of the 1st Conference of Metsovite Studies, Athens 1993, pp. 404.

- Yaycioglu, Ali (2016). Partners of the Empire: The Crisis of the Ottoman Order in the Age of Revolutions. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-9612-5.

Further reading

- Brøndsted, Peter Oluf, Interviews with Ali Pacha; edited by Jacob Isager, (Athens, 1998)

- Davenport, Richard, The Life of Ali Pasha, Late Vizier of Jannina; Surnamed Aslan, Or the Lion, (2nd ed, Relfe, London, 1822)

- Dumas père, Alexandre, Ali Pacha, Celebrated Crimes

- Fauriel, Claude Charles: Die Sulioten und ihre Kriege mit Ali Pascha von Janina, (Breslau, 1834)

- Glenny, Misha The Balkans 1804–1999 Granta Books, London 1999.

- Ilıcak, Şükrü, ed. (2021). Those Infidel Greeks: The Greek War of Independence through Ottoman Archival Documents. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-47129-0.

- Jóka, Mór: Janicsárok végnapjai, Pest, 1854. (in English: Maurus Jókai: The Lion of Janina, translated by R. Nisbet Bain, 1897). [1]

- Manzour, Ibrahim, Mémoires sur la Grèce et l'Albanie pendant le gouvernement d'Ali Pacha, (Paris, 1827)

- Plomer, William The Diamond of Jannina: Ali Pasha 1741–1822 (New York, Taplinger, 1970)

- Pouqueville, François, Voyage en Morée, à Constantinople, en Albanie, et dans plusieurs autres parties de l'Empire Ottoman (Paris, 1805, 3 vol. in-8°), translated in English, German, Greek, Italian, Swedish, etc. available on line at Gallica

- Pouqueville, François, Travels in Epirus, Albania, Macedonia, and Thessaly (London: printed for Sir Richard Phillips and Co, 1820), an English denatured and truncated edition available on line

- Pouqueville, François, Voyage en Grèce (Paris, 1820–1822, 5 vol. in-8° ; 20 édit., 1826–1827, 6 vol. in-8°), his capital work

- Pouqueville, François, Histoire de la régénération de la Grèce (Paris, 1824, 4 vol. in-8°), translated in many languages. French original edition available on Google books [2]

- Pouqueville, François, Notice sur la fin tragique d’Ali-Tébélen (Paris 1822, in-8°)

- Vaudoncourt, Guillaume de Memoirs on the Ionian Islands ... : including the life and character of Ali Pacha. London: Baldwin, Cradock and Joy, 1816

- "Visualizing Ali Pasha Order: Relations, Networks and Scales". Stanford University.

External links

Media related to Tepedelenli Ali Paşa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tepedelenli Ali Paşa at Wikimedia Commons

- Ali Pasha of Ioannina

- 1740 births

- 1822 deaths

- People from Tepelenë

- Albanian Muslims

- Pashas

- Civil servants from the Ottoman Empire

- 18th-century Albanian people

- 19th-century Albanian people

- 18th-century people from the Ottoman Empire

- 19th-century people from the Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman Greece

- Albanians from the Ottoman Empire

- Albanian nobility

- Albanian Pashas

- Albanian Sufis

- Anti-Aromanian sentiment

- Ottoman Sufis

- Bektashi Order

- Ottoman Ioannina

- Kirdzhalis