Carbon: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 168.8.175.2 identified as vandalism to last revision by Slashme. using TW |

|||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

C<sub>(s)</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>(g)</sub> → CO<sub>(g)</sub> + H<sub>2(g)</sub> |

C<sub>(s)</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>(g)</sub> → CO<sub>(g)</sub> + H<sub>2(g)</sub> |

||

and combines with some metals at high temperatures to form metallic carbides or reduces such metal oxides as iron oxide to the metal, especially in the iron and steel industry: |

and combines with some metals at high temperatures to form metallic carbides or reduces such metal oxides as iron oxide to the metal, especially in the iron and steel industry: |

||

Fe<sub>3</sub>O<sub>4</sub> + 4C<sub>(s)</sub> → 3Fe<sub>(s)</sub> +CO<sub>(g)</sub> |

Fe<sub>3</sub>O<sub>4</sub> + 4C<sub>(s)</sub> → 3Fe<sub>(s)</sub> +CO<sub>(g)</sub> |

||

Revision as of 16:15, 23 October 2007

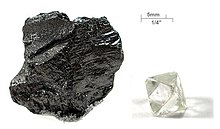

Graphite (left) and diamond (right), two allotropes of carbon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allotropes | graphite, diamond and more (see Allotropes of carbon) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbon in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 14 (carbon group) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s2 2p2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sublimation point | 3915 K (3642 °C, 6588 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | graphite: 2.266 g/cm3[3][4] diamond: 3.515 g/cm3 amorphous: 1.8–2.1 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 4600 K, 10,800 kPa[5][6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | graphite: 117 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | graphite: 8.517 J/(mol·K) diamond: 6.155 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: −4, +4 −3,[7] −2,[7] −1,[7] 0, +1,[7] +2,[7] +3[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.55 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | sp3: 77 pm sp2: 73 pm sp: 69 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 170 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | graphite: simple hexagonal (hP4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constants | a = 246.14 pm c = 670.94 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | diamond: face-centered diamond-cubic (cF8) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 356.707 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | diamond: 0.8 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C)[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | graphite: 119–165 W/(m⋅K) diamond: 900–2300 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | graphite: 7.837 µΩ⋅m[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | diamond: −5.9×10−6 cm3/mol[11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | diamond: 1050 GPa[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | diamond: 478 GPa[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | diamond: 442 GPa[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | diamond: 18,350 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | diamond: 0.1[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | graphite: 1–2 diamond: 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Egyptians and Sumerians[12] (3750 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized as an element by | Antoine Lavoisier[13] (1789) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of carbon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carbon (IPA: /ˈkɑː(ɹ)bən/) is a chemical element that has the symbol C and atomic number 6. An abundant nonmetallic, tetravalent element, carbon has several allotropic forms.

The abundance of carbon in the universe, along with the unusual polymer-forming ability of carbon-based compounds at the common temperatures encountered on Earth, make this element the basis of the chemistry of all known life.

The name "carbon" comes from Latin language carbo, coal. In some Romance languages, the word can refer both to the element and to coal.

Overview of carbon's importance on Earth

As the free element it forms allotropes from differing kinds of carbon-carbon bonds, such as in graphite and diamond. Coal is the main source of carbon in mineral form, containing up to 86% of carbon in anthracite. Recently discovered nanostructured forms called fullerenes include buckyballs such as C60, nanotubes, and nanofibers. Because of their high strength-to-weight ratio, it is hoped that many of these carbon compounds will soon be practical for use in advanced structural composite materials.

Not only can carbon bond with itself, but it can also form chains with a wide variety of other elements, forming nearly ten million known compounds.

Carbon-containing polymers, often with oxygen and nitrogen ions included at regular intervals in the main polymer chain, form the basis of nearly all industrial commercial plastics.

Carbon occurs in all organic life and is the basis of organic chemistry. When united with oxygen, carbon forms carbon dioxide, which is the main carbon source for plant growth. When united with hydrogen, it forms various flammable compounds called hydrocarbons which are essential to industry in the form of fossil fuels, and also other important living plant components like carotenoids and terpenes. When combined with oxygen and hydrogen, carbon can form many groups of important biological compounds including sugars, celluloses, lignans, chitins, alcohols, fats, and aromatic esters. With nitrogen it forms alkaloids, and with the addition of sulfur also it forms antibiotics, amino acids and proteins. With the addition of phosphorus to these other elements, it forms DNA and RNA, the chemical codes of life.

Notable characteristics of carbon

Carbon exhibits remarkable properties, some paradoxical. Different forms include the hardest naturally occurring substance (diamond) and one of the softest substances (graphite) known. Moreover, it has a great affinity for bonding with other small atoms, including other carbon atoms, and is capable of forming multiple stable covalent bonds with such atoms. Because of these properties, carbon is known to form nearly ten million different compounds, the large majority of all chemical compounds. Carbon compounds form the basis of all life on Earth and the carbon-nitrogen cycle provides some of the energy produced by the Sun and other stars. Moreover, carbon has the highest melting/sublimation point of all elements. At atmospheric pressure it has no actual melting point as its triple point is at 10 MPa (100 bar) so it sublimates above 4000 K. Thus it remains solid at higher temperatures than the highest melting point metals like tungsten or rhenium, irrespective of its allotropic form. Although thermodynamically prone to oxidation, it resists oxidation more effectively than some elements (like iron and even copper) that are weaker reducing agents at room temperature.

Although it forms an incredible variety of compounds, most forms of carbon are comparatively unreactive under normal conditions. At standard temperature and pressure, it resists all but the strongest oxidizers ( fluorine and nitric acid are the most common chemicals to react with carbon). It does not react with sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, chlorine or any alkalis. At elevated temperatures it of course reacts with oxygen in flames to form carbon oxides and with sulfur vapors to form carbon disulfide or steam in the coal-gas reaction

C(s) + H2O(g) → CO(g) + H2(g)

and combines with some metals at high temperatures to form metallic carbides or reduces such metal oxides as iron oxide to the metal, especially in the iron and steel industry:

Fe3O4 + 4C(s) → 3Fe(s) +CO(g)

Formation in Stars

Formation of the carbon atomic nucleus requires a nearly simultaneous triple collision of alpha particles (helium nuclei) within a the core of a giant or supergiant star. This happens in temperature and helium concentration conditions that the rapid expansion and cooling of the early universe prohibited, and therefore no significant carbon was created during the Big Bang. Instead, the interiors of stars in the horizontal branch transform three helium nuclei into carbon by means of this triple-alpha process. In order to be available for formation of life as we know it, this carbon must then later be scattered into space as dust, in supernovae explosions, as part of the material which later forms second-generation star systems which have planets accreted from such dust. The solar system is one such second-generation star system, made from elements in the dust of dozens of supernovae in its local area of the galaxy.

Applications

Carbon is essential to all known living systems, and without it life as we know it could not exist (see alternative biochemistry). The major economic use of carbon not in living or formerly-living material (such as food and wood) is in the form of hydrocarbons, most notably the fossil fuel methane gas and crude oil (petroleum). Crude oil is used by the petrochemical industry to produce, amongst others, gasoline and kerosene, through a distillation process, in refineries. Crude oil forms the raw material for many synthetic substances, many of which are collectively called plastics.

Other uses

- The isotope carbon-14 was discovered on February 27 1940 by Martin Kamen and is used in radiocarbon dating.

- Industrial diamonds are used in cutting, drilling, and polishing technologies.

- Graphite is combined with clays to form the 'lead' used in pencils. It is also used as a lubricant and a pigment.

- Diamond is used for decorative purposes, and as drill bits and other applications making use of its hardness.

- Carbon (usually as coke) is used to reduce iron ore into iron.

- Carbon is added to iron to make steel.

- Carbon is used as a neutron moderator in nuclear reactors.

- Carbon fiber, which is mainly used for composite materials, as well as high-temperature gas filtration.

- Carbon black is used as a filler in rubber and plastic compounds.

- Graphite carbon in a powdered, caked form is used as charcoal for grilling, artwork and other uses.

- Activated charcoal is used in medicine (as powder or compounded in tablets or capsules) to absorb toxins, poisons, or gases from the digestive system.

- Carbon, due to its non-reactivity with many substances that corrode most materials, is often used as an electrode.

- The chemical and structural properties of fullerenes, in the form of carbon nanotubes, has promising potential uses in the nascent field of nanotechnology.

- Rotational transitions of various isotopic forms of carbon monoxide (e.g. 12CO, 13CO, and 18CO) are detectable in the submillimeter regime, and are used in the study of newly forming stars in molecular clouds.

History and etymology

It was discovered in prehistory and was known to the ancients, who manufactured it by burning organic material in insufficient oxygen (making charcoal). It is also found in abundance in the Sun, stars, comets, and atmospheres of most planets. Carbon in the form of microscopic diamonds is found in some meteorites.

Natural diamonds are found in kimberlite of ancient volcanic "pipes," found in South Africa, Arkansas, Northern Canada and elsewhere. Diamonds are now also being recovered from the ocean floor off the Cape of Good Hope. About 30% of all industrial diamonds used in the U.S. are now made synthetically.

The energy of the Sun and stars can be attributed at least in part to the carbon-nitrogen cycle.

The name of Carbon comes from Latin carbo, hence comes French charbone, meaning charcoal. In German, Dutch and Danish, the names for carbon are Kohlenstoff, koolstof and kulstof respectively, all literally meaning coal-matter.

Allotropes

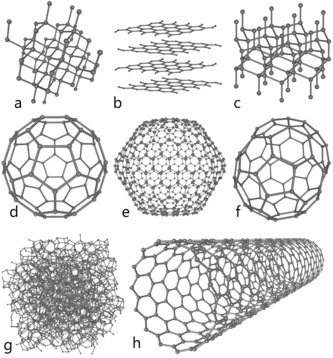

The allotropes of carbon are the different molecular configurations that pure carbon can take.

The three relatively well-known allotropes of carbon are amorphous carbon, graphite, and diamond. Several exotic allotropes have also been synthesized or discovered, including fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, carbon nanobuds, lonsdaleite and aggregated diamond nanorods.

In its amorphous form, carbon is essentially graphite but not held in a crystalline macrostructure. It is, rather, present as a powder which is the main constituent of substances such as charcoal, lampblack (soot) and activated carbon.

At normal pressures carbon takes the form of graphite, in which each atom is bonded to three others in a plane composed of fused hexagonal rings, just like those in aromatic hydrocarbons. The two known forms of graphite, alpha (hexagonal) and beta (rhombohedral), both have identical physical properties, except for their crystal structure. Graphites that naturally occur have been found to contain up to 30% of the beta form, when synthetically-produced graphite only contains the alpha form. The alpha form can be converted to the beta form through mechanical treatment and the beta form reverts to the alpha form when it is heated above 1000 °C.

Because of the delocalization of the π-cloud, graphite conducts electricity. This accounts for the energetic stability of graphite over diamond at room temperature. Graphite is soft and the sheets, frequently separated by other atoms, are held together only by Van der Waals forces, so easily slip past one another.

At very high pressures carbon forms an allotrope called diamond, in which each atom is bonded to four others. Diamond has the same cubic structure as silicon and germanium and, thanks to the strength of the carbon-carbon bonds, is together with the isoelectronic boron nitride (BN) the hardest substance in terms of resistance to scratching. The transition to graphite at room temperature,although more stable, is so slow as to be unnoticeable, due to a high activation energy barrier. Under some conditions, carbon crystallizes as Lonsdaleite, a form similar to diamond but hexagonal.

Fullerenes have a graphite-like structure, but instead of purely hexagonal packing, also contain pentagons (or possibly heptagons) of carbon atoms, which bend the sheet into spheres, ellipses or cylinders. The properties of fullerenes (also called "buckyballs" and "buckytubes") have not yet been fully analyzed. The name "fullerene" is given after Richard Buckminster Fuller, developer of some geodesic domes, which resemble the structure of fullerenes.

A ferromagnetic nanofoam allotrope has also been discovered.

Carbon allotropes include:

- Diamond: Hardest known natural mineral. Structure: each atom is bonded tetrahedrally to four others, making a 3-dimensional network of puckered six-membered rings of atoms.

- Graphite: One of the softest substances. Structure: each atom is bonded trigonally to three other atoms, making a 2-dimensional network of flat six-membered rings; the flat sheets are loosely bonded.

- Fullerenes: Structure: comparatively large molecules formed completely of carbon bonded trigonally, forming spheroids (of which the best-known and simplest is the buckminsterfullerene or buckyball, because of its soccerball-shaped structure).

- Chaoite: A mineral believed to be formed in meteorite impacts.

- Lonsdaleite: A corruption of diamond. Structure: similar to diamond, but forming a hexagonal crystal lattice.

- Amorphous carbon: A glassy substance. Structure: an assortment of carbon atoms in a non-crystalline, irregular, glassy state.

- Carbon nanofoam (discovered in 1997): An extremely light magnetic web. Structure: a low-density web of graphite-like clusters, in which the atoms are bonded trigonally in six- and seven-membered rings.

- Carbon nanotubes: Tiny tubes. Structure: each atom is bonded trigonally in a curved sheet that forms a hollow cylinder.

- Nanobud: A hybrid carbon nanotube/fullerene material first published in 2007 which combines the properties of both in a single structure in which fullerenes are covalently bonded to the outer wall of a nanotube.

- Aggregated diamond nanorods (synthesised in 2005): The most recently discovered allotrope and the hardest substance known.

- Lampblack: Consists of small graphitic areas. These areas are randomly distributed, so the whole structure is isotropic.

- 'Glassy carbon': An isotropic substance that contains a high proportion of closed porosity. Unlike normal graphite, the graphitic layers are not stacked like pages in a book, but have a more random arrangement.

Carbon fibers are similar to glassy carbon. Under special treatment (stretching of organic fibers and carbonization) it is possible to arrange the carbon planes in direction of the fiber. Perpendicular to the fiber axis there is no orientation of the carbon planes. The result are fibers with a higher specific strength than steel.

The system of carbon allotropes spans a range of extremes:

- Diamond is the hardest mineral known to man (although aggregated diamond nanorods are now believed to be even harder), while graphite is one of the softest.

- Diamond is the ultimate abrasive, while graphite is a very good lubricant.

- Diamond is an excellent electrical insulator, while graphite is a conductor of electricity.

- Diamond is an excellent thermal conductor, while some forms of graphite are used for thermal insulation (i.e. firebreaks and heatshields)

- Diamond is usually transparent, while graphite is opaque.

- Diamond crystallizes in the cubic system while graphite crystallizes in the hexagonal system.

- Amorphous carbon is completely isotropic, while carbon nanotubes are among the most anisotropic materials ever produced.80's

Occurrence

Carbon is the fourth most abundant chemical element in the universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen (see Abundance of the chemical elements). Carbon is abundant in the Sun, stars, comets, and in the atmospheres of most planets. Some meteorites contain microscopic diamonds that were formed when the solar system was still a protoplanetary disk. In combination with other elements, carbon is found in the Earth's atmosphere (around 810 gigatonnes) and dissolved in all water bodies (around 36000 gigatonnes). Around 1900 gigatonnes are present in the biosphere. Hydrocarbons (such as coal, petroleum, and natural gas) contain carbon as well — coal "resources" amount to around 1000 gigatonnes, and oil reserves around 150 gigatonnes. With smaller amounts of calcium, magnesium, and iron, carbon is a major component of very large masses carbonate rock (limestone, dolomite, marble etc.).

Graphite is found in large quantities in New York and Texas, the United States; Russia; Mexico; Greenland and India.

Natural diamonds occur in the mineral kimberlite found in ancient volcanic "necks," or "pipes". Most diamond deposits are in Africa, notably in South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, the Republic of the Congo and Sierra Leone. There are also deposits in Arkansas, Canada, the Russian Arctic, Brazil and in Northern and Western Australia.

According to studies from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, an estimate of the global carbon budget is:[citation needed]

| Biosphere, oceans, atmosphere | |

|---|---|

| 0.45 x 1018 kilograms (3.7 x 1018 moles) | |

| Crust | |

| Organic carbon | 13.2 x 1018 kg |

| Carbonates | 62.4 x 1018 kg |

| Mantle | |

| 1200 x 1018 kg | |

Organic compounds

The most prominent oxide of carbon is carbon dioxide, CO2. This is a minor component of the Earth's atmosphere, produced and used by living things, and a common volatile elsewhere. In water it forms trace amounts of carbonic acid, H2CO3, but as most compounds with multiple single-bonded oxygens on a single carbon it is unstable. Through this intermediate, though, resonance-stabilized carbonate ions are produced. Some important minerals are carbonates, notably calcite. Carbon disulfide, CS2, is similar.

The other oxides are carbon monoxide, CO, the uncommon carbon suboxide, C3O2, the uncommon dicarbon monoxide, C2O and even carbon trioxide, CO3. Carbon monoxide is formed by incomplete combustion, and is a colorless, odorless gas. The molecules each contain a triple bond and are fairly polar, resulting in a tendency to bind permanently to hemoglobin molecules, displacing oxygen, which has a lower binding affinity. Cyanide, CN-, has a similar structure and behaves much like a halide ion; the nitride cyanogen, (CN)2, is related.

With reactive metals, such as tungsten, carbon forms either carbides, C-, or acetylides, C22- to form alloys with high melting points. These anions are also associated with methane and acetylene, both very weak acids. All in all, with an electronegativity of 2.5, carbon prefers to form covalent bonds. A few carbides are covalent lattices, like carborundum, SiC, which resembles diamond.

Carbon has the ability to form long, indefinite chains with interconnecting C-C bonds. This property is called catenation. Carbon-carbon bonds are strong, and stable. This property allows carbon to form an infinite number of compounds; in fact, there are more known carbon-containing compounds than all the compounds of the other chemical elements combined except those of hydrogen (because almost all carbon compounds contain hydrogen).

The simplest form of an organic molecule is the hydrocarbon - a large family of organic molecules that, by definition, are composed of hydrogen atoms bonded to a chain of carbon atoms. Chain length, side chains and functional groups all affect the properties of organic molecules.

Nearly ten million carbon compounds are known, and thousands of these are vital to life processes. They are also many organic-based reactions of economic importance.

Carbon cycle

Under terrestrial conditions, conversion of one element to another is very rare. Therefore, for practical purposes, the amount of carbon on Earth is constant. Thus processes that use carbon must obtain it somewhere and dispose of it somewhere. The paths that carbon follows in the environment make up the carbon cycle. For example, plants draw carbon dioxide out of the environments and use it to build biomass, as in carbon respiration. Some of this biomass is eaten by animals, where some of it is exhaled as carbon dioxide. The carbon cycle is considerably more complicated than this short loop; for example, some carbon dioxide is dissolved in the oceans; dead plant or animal matter may become petroleum or coal which can burn with the release of carbon dioxide should bacteria not consume it.

Isotopes

Carbon has two stable, naturally-occurring isotopes: carbon-12, or 12C, (98.89%) and carbon-13, or 13C, (1.11%), and one unstable, naturally-occurring, radioisotope; carbon-14 or 14C. There are 15 known isotopes of carbon and the shortest-lived of these is 8C which decays through proton emission and alpha decay. It has a half-life of 1.98739x10-21 s.

In 1961 the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry adopted the isotope carbon-12 as the basis for atomic weights.

Carbon-14 has a half-life of 5730 y and has been used extensively for radiocarbon dating carbonaceous materials.

The exotic 19C exhibits a nuclear halo.

Precautions

Although carbon is relatively safe due to low toxicity and resistance to most chemical attacks (including fire and the acidic contents of the digestive tract) at normal temperatures, inhalation of fine soot in large quantities can be dangerous. Diamond dust can do harm as an abrasive if ingested or inhaled. Carbon may also spawn flames at very high temperatures and burn vigorously and brightly (as in the Windscale fire).

The great variety of carbon compounds include such lethal poisons as cyanide (CN-), and carbon monoxide; and such essentials to life as glucose and protein.

See also

- Organic chemistry

- Inorganic chemistry of carbon

- Allotropes of carbon

- Diamond

- Material properties of diamond

- Carbon nanotube

- Low-carbon economy

- Atomic carbon

- Carbon chauvinism

- Fullerene

References

- On Graphite Transformations at High Temperature and Pressure Induced by Absorption of the LHC Beam, J.M. Zazula, 1997

- http://WebElements.com

- http://EnvironmentalChemistry.com

External links

- Los Alamos National Laboratory – Carbon

- WebElements.com – Carbon

- Chemicool.com – Carbon

- It's Elemental – Carbon

- – Carbon Fullerene and other Allotropes models by Vincent Herr

- Extensive Carbon page at asu.edu

- Electrochemical uses of carbon

- Computational Chemistry Wiki

- Carbon - Super Stuff. Animation with sound and interactive 3D-models.

- BBC Radio 4 series "In Our Time", on Carbon, the basis of life, 15 June 2006

- Introduction to Carbon Properties geared for High School students.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Carbon". CIAAW. 2009.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (2022-05-04). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Haaland, D (1976). "Graphite-liquid-vapor triple point pressure and the density of liquid carbon". Carbon. 14 (6): 357–361. doi:10.1016/0008-6223(76)90010-5.

- ^ Savvatimskiy, A (2005). "Measurements of the melting point of graphite and the properties of liquid carbon (a review for 1963–2003)". Carbon. 43 (6): 1115–1142. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2004.12.027.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ a b c d e Properties of diamond, Ioffe Institute Database

- ^ "Material Properties- Misc Materials". www.nde-ed.org. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 81st edition, CRC press.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 978-0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ "History of Carbon and Carbon Materials - Center for Applied Energy Research - University of Kentucky". Caer.uky.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ Senese, Fred (2000-09-09). "Who discovered carbon?". Frostburg State University. Retrieved 2007-11-24.