History of Brazil: Difference between revisions

→Beginnings of Brazil: grammar |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

{{See also|Indigenous peoples in Brazil}} |

{{See also|Indigenous peoples in Brazil}} |

||

Fossil records found in [[Minas Gerais]] show evidence that the area now called Brazil has been inhabited for at least 8,000 years by indigenous people.<ref>Levine, R.M., & Crocitti, J.J. (1999). [http://books.google.com/books?id=R28K2JA9PM8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Brazil+reader:+History,+culture,+politics. ''The Brazil reader: History, culture, politics.''] p.[http://books.google.com/books?id=R28K2JA9PM8C&pg=PA11 11]. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.</ref> The dating of the origins of the first inhabitants, who were called "Indians" (''índios'') by the Portuguese, are still a matter of dispute among |

Fossil records found in [[Minas Gerais]] show evidence that the area now called Brazil has been inhabited for at least 8,000 years by indigenous people.<ref>Levine, R.M., & Crocitti, J.J. (1999). [http://books.google.com/books?id=R28K2JA9PM8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Brazil+reader:+History,+culture,+politics. ''The Brazil reader: History, culture, politics.''] p.[http://books.google.com/books?id=R28K2JA9PM8C&pg=PA11 11]. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.</ref> The dating of the origins of the first inhabitants, who were called "Indians" (''índios'') by the Portuguese, are still a matter of dispute among archaeologists. The current most widely accepted view of anthropologists, linguists and geneticists is that they were part of the first wave of migrant hunters who came into the [[Americas]] from [[Asia]], either by land, across the [[Bering Strait]], or by coastal sea routes along the Pacific, or both. |

||

The [[Andes]] and the mountain ranges of northern South America created a rather sharp cultural boundary between the settled agrarian civilizations of the west coast (which gave rise to urbanized city-states and the immense [[Inca Empire]]) and the semi-nomadic tribes of the east, who never developed written records or permanent monumental architecture. For this reason, very little is known about the history of Brazil before 1500. Archaeological remains (mainly [[pottery]]) indicate a complex pattern of regional cultural developments, internal migrations, and occasional large state-like federations. |

The [[Andes]] and the mountain ranges of northern South America created a rather sharp cultural boundary between the settled agrarian civilizations of the west coast (which gave rise to urbanized city-states and the immense [[Inca Empire]]) and the semi-nomadic tribes of the east, who never developed written records or permanent monumental architecture. For this reason, very little is known about the history of Brazil before 1500. Archaeological remains (mainly [[pottery]]) indicate a complex pattern of regional cultural developments, internal migrations, and occasional large state-like federations. |

||

Revision as of 05:16, 30 August 2011

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Brazil |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Brazil begins with the arrival of the first indigenous peoples, thousands of years ago by crossing the Bering land bridge into Alaska and then entering the rest of North and Central America.

It is widely accepted that the European first to discover Brazil was Portuguese Pedro Álvares Cabral on April 22, 1500. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, Brazil was a colony of Portugal. On September 7, 1822, the country declared its independence from Portugal and became a constitutional monarchy, the Empire of Brazil. A military coup in 1889 established a republican government. The country has seen a dictatorship (1930–1934 and 1937–1945) and a period of military rule (1964–1985).

Pre-Colonial history

Fossil records found in Minas Gerais show evidence that the area now called Brazil has been inhabited for at least 8,000 years by indigenous people.[1] The dating of the origins of the first inhabitants, who were called "Indians" (índios) by the Portuguese, are still a matter of dispute among archaeologists. The current most widely accepted view of anthropologists, linguists and geneticists is that they were part of the first wave of migrant hunters who came into the Americas from Asia, either by land, across the Bering Strait, or by coastal sea routes along the Pacific, or both.

The Andes and the mountain ranges of northern South America created a rather sharp cultural boundary between the settled agrarian civilizations of the west coast (which gave rise to urbanized city-states and the immense Inca Empire) and the semi-nomadic tribes of the east, who never developed written records or permanent monumental architecture. For this reason, very little is known about the history of Brazil before 1500. Archaeological remains (mainly pottery) indicate a complex pattern of regional cultural developments, internal migrations, and occasional large state-like federations.

At the time of European discovery, the territory of current day Brazil had as many as 2,000 nations and tribes. The indigenous peoples were traditionally mostly semi-nomadic tribes who subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering, and migrant agriculture. When the Portuguese arrived in 1500, the Natives were living mainly on the coast and along the banks of major rivers. Initially, the Europeans saw the natives as noble savages, and miscegenation of the population began right away. Tribal warfare, cannibalism and the pursuit of Amazonian brazilwood (see List of meanings of countries' names) for its treasured red dye convinced the Portuguese that they should "civilize" the Natives. But the Portuguese, like the Spanish in their South American possessions, had unknowingly brought diseases with them, against which many Natives were helpless due to lack of immunity. Measles, smallpox, tuberculosis and influenza killed tens of thousands. The diseases spread quickly along the indigenous trade routes, and whole tribes were likely annihilated without ever coming in direct contact with Europeans.

Beginnings of Brazil

There are several theories regarding who first set foot on the land now called Brazil (the origin of whose name is disputed). Besides the widely accepted view of Cabral's discovery, some defend that it was Duarte Pacheco Pereira between november and December of 1498 [2][3] and some others say that it was first discovered by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, a Spanish navigator that had accompanied Colombus in his first trip to the American continent having supposedly arrived to today's Pernambuco region on 26 January of 1500[citation needed]. In April 1500, however, Brazil was claimed by Portugal on the arrival of the Portuguese fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral.[4] The Portuguese encountered stone age natives divided into several tribes, most of whom shared the same Tupi–Guarani language family, and fought among themselves.[5]

Until 1530 Portugal had very little interest in Brazil, mainly due to the high profits gained through commerce with India, China, and Indonesia. This lack of interest led to several "invasions" by different countries, and the Portuguese Crown devised a system to effectively occupy Brazil, without paying the costs. Through the Hereditary Captaincies system, Brazil was divided into strips of land that were donated to Portuguese noblemen, who were in turn responsible for the occupation of the land and answered to the king. Later, the Portuguese realized the system was a failure, only two lots were successfully occupied (Pernambuco and São Vicente, in the current state of São Paulo), and took control of the country after its European discovery, the land's major export—giving its name to Brazil (another contested hypothesis)—was brazilwood, a large tree (Caesalpinia echinata) whose trunk contains a prized red dye, and which was nearly wiped out as a result of overexploitation. Starting in the 17th century, sugarcane culture, grown in plantation's property called engenhos ("factories") along the northeast coast (Brazil's Nordeste) It became the base of Brazilian economy and society, with the use of black slaves on large plantations to make sugar production for export to Europe. At first, settlers tried to enslave the Natives as labor to work the fields. (The initial exploration of Brazil's interior was largely due to para-military adventurers, the bandeirantes, who entered the jungle in search of gold and Native slaves.) However the Natives were found to be unsuitable as slaves, and so the Portuguese land owners turned to Africa, from which they imported millions of slaves.

During the first two centuries of the colonial period, attracted by the vast natural resources and untapped land, other European powers tried to establish colonies in several parts of Brazilian territory, in defiance of the papal bull ( Inter caetera ) and the Treaty of Tordesillas, which had divided the New World into two parts between Portugal and Spain. French colonists tried to settle in present-day Rio de Janeiro, from 1555 to 1567 (the so-called France Antarctique episode), and in present-day São Luís, from 1612 to 1614 (the so called France Équinoxiale).

The unsuccessful Dutch intrusion into Brazil was longer lasting and more troublesome to Portugal ( Dutch Brazil ). Dutch privateers began by plundering the coast: they sacked Bahia in 1604, and even temporarily captured the capital Salvador. From 1630 to 1654, the Dutch set up more permanently in the Nordeste and controlled a long stretch of the coast most accessible to Europe, without, however, penetrating the interior. But the colonists of the Dutch West India Company in Brazil were in a constant state of siege, in spite of the presence in Recife of the great John Maurice of Nassau as governor. After several years of open warfare, the Dutch formally withdrew in 1661. Little French and Dutch cultural and ethnic influences remained of these failed attempts.

Mortality rates for slaves in sugar and gold enterprises were dramatic, and there were often not enough females or proper conditions to replenish the slave population indigenously. Some slaves escaped from the plantations and tried to establish independent settlements (quilombos) in remote areas. The most important of these, the quilombo of Palmares, was the largest slave runaway settlement in the Americas, and was a consolidated kingdom of some 30,000 people at its height in the 1670s and 80s. However these settlements were mostly destroyed by government and private troops, which in some cases required long sieges and the use of artillery. Still, Africans became a substantial section of Brazilian population, and long before the end of slavery (1888) they had begun to merge with the European Brazilian population through miscegenation and mulatto work rights.

The Empire of Brazil

Brazil was one of only three modern states in the Americas to have its own indigenous monarchy (the other two were Mexico and Haiti) - for a period of almost 90 years. In an unusual reversal, Brazil, rather than Portugal itself, was the metropole of the Portuguese Empire from 1808 to 1821.

In 1808, the Portuguese court, fleeing from Napoleon's invasion of Portugal during the Peninsular War in a large fleet escorted by British men-of-war, moved the government apparatus to its then-colony, Brazil, establishing themselves in the city of Rio de Janeiro. From there the Portuguese king ruled his huge empire for 13 years, and there he would have remained for the rest of his life if it were not for the turmoil aroused in Portugal due, among other reasons, to his long stay in Brazil after the end of Napoleon's reign.

In 1815 the king vested Brazil with the dignity of a united kingdom with Portugal and Algarves. When king João VI of Portugal left Brazil to return to Portugal in 1821, his elder son, Pedro, stayed in his stead as regent of Brazil. One year later, Pedro stated the reasons for the secession of Brazil from Portugal and led the Independence War, instituted a constitutional monarchy in Brazil assuming its head as Emperor Pedro I of Brazil.

Also known as "Dom Pedro I", after his abdication in 1831 for political incompatibilities (displeased, both by the landed elites, who thought him too liberal and by the intellectuals, who felt he was not liberal enough), he left for Portugal leaving behind his five-year-old son as Emperor Pedro II, which led the country ruled by regents between 1831 and 1840. This period was beset by rebellions of various motivations, such as the Sabinada, the War of the Farrapos, the Malê Revolt,[6] Cabanagem and Balaiada, among others. After this period, Pedro II was declared of age and assumed his full prerogatives. Pedro II started a more-or-less parliamentary reign which lasted until 1889, when he was ousted by a coup d'état which instituted the republic in Brazil.

Externally, apart from the Independence war, stood out decades of pressure from the United Kingdom for the country to end its participation in the Slave Traffic, and the wars fought in the region of La Plata river: the Cisplatine War (in 2nd half of 1820s), the War against Oribe & Rosas (in 1850s), the War against Aguirre and the Great War of La Plata (in the 1860s). This last war against Paraguay also was the bloodiest and most expensive in South American history, after which the country entered a period that continues to the present day, averse to external political and military interventions.

The Old Republic (1889–1930)

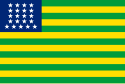

Pedro II was deposed on November 15, 1889, by a Republican military coup led by General Deodoro da Fonseca, who became the country's first de facto president through military ascension. The country's name became the Republic of the United States of Brazil (which in 1967 was changed to Federative Republic of Brazil.).

From 1889 to 1930, although the country was formally a constitutional democracy, in practice women and the illiterate (then the majority of the population) were prevented from voting. Also, to ensure that the outcome of the polls reflected the will of the landlords, the vote also was not secret, with the presidency alternating between the dominant states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais. Thus, the first Republican period was rife with economic turmoil, followed by political and social rebellions subdued by the regime. Between 1893 and 1926 several movements, civilians and military, shook the country. The military movements had their origins both in the low officership's corps of the Army and Navy (which, dissatisfied with the regime, called for democratic changes) while the civilian ones, such Canudos and Contestado War, were usually led by messianic leaders, without conventional political goals.

Internationally, the country would stick to a course of conduct that extended throughout the twentieth century: an almost isolationist policy, interspersed with sporadic automatic alignments with major western powers, its main economic partners, in moments of high turbulence. Standing out from this period: the resolution of the Acreanian's Question and the tiny role in the World War I (basically limited to the anti-submarine warfare).[7]

This period, known as the "Old Republic", ended in 1930 with a military coup that placed Getúlio Vargas in the presidency.

Populism and development (1930–1964)

After 1930, the successive governments continued industrial and agriculture growth and development of the vast interior of Brazil. Getúlio Vargas led a military junta that had took control in 1930 and would remain ruling from 1930 to 1945 with the backing of Brazilian military, especially the Army. In this period, he faced internally the Constitutionalist Revolt in 1932 and two separate coup d’état attempts: by Communists in 1935 and by local Fascists in 1938.

A democratic regime prevailed from 1945–64. In the 1950s after Vargas' second period (this time, democratically elected), the country experienced an economic boom during Juscelino Kubitschek's years, during which the capital was moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília.

Externally, after a relative isolation during the first half of the 1930s due to the effects of the 1929 Crisis. In the second half of the 1930s, there was a rapprochement with the fascist regimes of Italy and Germany. However, after the fascist coup attempt in 1938 and the naval blockade imposed on these two countries by the British navy from the beginning of World War II, in the decade of 1940 there was a return to the old foreign policy of the previous period. During the 1940s, Brasil joined the allied forces at Battle of Atlantic and in the Italian Campaign during WWII; in the 1950s the country began its participation in the United Nations' peacekeeping missions[8] with Suez Canal in 1956 and in the beginning of the 1960s, during the presidency of Janio Quadros, the first attempts to break the automatic alignment (that had started in the 1940s)[9] with the U.S.A.

The institutional crisis of succession for the presidency, triggered with the Quadros' resignation, coupled with other factors, would lead to the military coup of 1964 and to the end of this period.

Military dictatorship (1964–85)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

New Professionalism and the Escola Superior de Guerra

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the success of revolutionary warfare techniques against conventional armies in China, Indochina, Algeria, and Cuba led the conventional armies in the developed and underdeveloped worlds to concentrate on finding military and political strategies to fight domestic revolutionary warfare. This led to an adoption of what Stepan called, in 1973, “New Professionalism.” The New Professionalism was formulated and propagated in Brazil through the Escola Superior de Guerra, which had been established in 1949. By 1963 New Professionalism had come to dominate the school, when it declared its primary mission to be preparing “civilians and the military to perform executive and advisory functions (Decreto Lei No. 53,080 December 4, 1963).” This new attitude towards professionalism did not arise out of nowhere. Though its domination of the ESG was completed by 1963, it had begun to penetrate the college much earlier than that — assisted by the United States and its policy of encouraging Latin American militaries to assume as their primary role in counter-guerrilla and counter-insurgency warfare programs, civic action and nation-building tasks.[10]

By 1964, at the same time that the military elite were unsatisfied with the natural delay, transfers and accommodation, characteristics of the negotiation processes in democratic regimes and was also eager to impose their development project, saw a leftist revolution as a real possibility (through the paradigm of internal warfare doctrines of the new professionalism). Events like the rising strike levels, the inflation rate, embraced demands by the Left for broaden political process, land reform and the growing claims of the enlisted men were seen as "evidence" that Brazil was facing the serious possibility of a leftist internal insurgency.[11]

Knocking on the barracks door

From 1961 to 1964, Brazilian President João Goulart had been initiating economic and social reforms that were clearly failing to address the economic problems of the country; policies which satisfied neither Brazil's elites nor its increasingly mobilized working classes. The cost of living index, rather low in late 1950s began to rise sharply, and per capita GDP growth fell sharply, from 4.5% in 1957 to negative growth by 1963[citation needed]. Goulart also began to take steps that alienated the Brazilian military and stoked their worst fears of revolutionary leftism.[citation needed] Goulart was a member of the wealthy agrarian elite of the country, was a Catholic, possessed huge amounts of land and supported the United States during the Cuban missiles crisis.[citation needed] But he also tolerated communists within his government, pursued a neutralist foreign policy, passed a law limiting the amount of profits multinationals could transmit out of the country, a subsidiary of ITT was nationalized and showed favoritism towards military officers labelled "ultra-nationalist" (he claimed they were loyal to him), which worried the pro-American national military and the United States government, concerned that Goulart could be too leftist for their tastes.[12]

Military response

By early 1964 important sections of the military had developed a consensus that intervention in the political process was necessary. The development of this consensus was likely helped by important civilian politicians, such as José de Magalhães Pinto, governor of Minas Gerais, and the United States government. Though many in the right of the political spectrum claim the coup was "revolutionary," most historians agree that that is not so, since there was no real transition of power; military dictatorship was the fastest way to implement neoliberal economic policies in the country while suppressing growing popular discontent, and the coup was thus a way for Brazil's already-ruling elite to secure its power. At first, there was intense economic growth, due to neoliberal economic reforms, but in the later years of the dictatorship, the reforms had left the economy in shambles, with soaring inequality and national debt, and thousands of Brazilians were deported, imprisoned, tortured,[13] or murdered. Politically motivated deaths numbered in the hundreds, mostly related to the guerrilla-antiguerrilla warfare in the 1968–73 period; official censorship also led many artists into exile.

Redemocratization to present (1985–Present)

Tancredo Neves was elected president in an indirect election in 1985 as the nation returned to civilian rule. He died before being sworn in, and the elected vice president, José Sarney, was sworn in as president in his place.

Fernando Collor de Mello was the first elected president by popular vote after the military regime in December 1989 defeating Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in a two round presidential race and 35 million votes. This victory owed partly to Rede Globo's coverage of the pair's presidential debate. The network gave Collor more airtime than Lula and juxtaposed his most eloquent statements with his socialist rival's least impressive moments. Years later Globo would actually apologise for their editing of this debate. Collor won in the state of São Paulo against many prominent political figures. The first democratically elected President of Brazil in 29 years, Collor spent much of the early years of his government battling hyper-inflation, which at times reached rates of 25% per month.

Collor's neoliberal program was also followed by his successor Fernando Henrique Cardoso[14] who maintained free trade and privatization programs.[15] Collor's administration began the process of privatization of a number of government-owned enterprises such as Acesita, Embraer, Telebrás and Companhia Vale do Rio Doce.[16] With the exception of Acesita, the privatizations were all completed during the term of Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

Following Collor's impeachment, acting president, Itamar Franco, was sworn in as president. In elections held on October 3, 1994, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, his finance minister, defeated left-wing Lula da Silva again. He was elected president due to the success of the so called Plano Real. Reelected in 1998, he guided Brazil through a wave of financial crises. In 2000, Cardoso ordered the declassifying of some military files concerning Operation Condor, a network of South American military dictatorships that kidnapped and assassinated political opponents.

Brazil's most severe problem today is arguably its highly unequal distribution of wealth and income, one of the most extreme in the world. By the 1990s, more than one out of four Brazilians continued to survive on less than one dollar a day. These socio-economic contradictions helped elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) in 2002.

In the few months before the election, investors were scared by Lula's campaign platform for social change, and his past identification with labor unions and leftist ideology. As his victory became more certain, the Real devalued and Brazil's investment risk rating plummeted (the causes of these events are disputed, since Cardoso left a very small foreign reserve). After taking office, however, Lula maintained Cardoso's economic policies,[17] warning that social reforms would take years and that Brazil had no alternative but to extend fiscal austerity policies. The Real and the nation's risk rating soon recovered.

Lula, however, has given a substantial increase to the minimum wage (raising from R$200 to R$350 in four years). Lula also spear-headed legislation to drastically cut retirement benefits for public servants. His primary significant social initiative, on the other hand, was the Fome Zero (Zero Hunger) program, designed to give each Brazilian three meals a day.

In 2005 Lula's government suffered a serious blow with several accusations of corruption and misuse of authority against his cabinet, forcing some of its members to resign. Most political analysts at the time were certain that Lula's political career was doomed, but he managed to hold onto power, partly by highlighting the achievements of his term (e.g., reduction in poverty, unemployment and dependence on external resources, such as oil), and to distance himself from the scandal. Lula was re-elected President in the general elections of October, 2006.

Having served two terms as president, Lula was forbidden by the Brazilian Constitution from standing again. In the 2010 presidential election, the PT candidate was Dilma Rousseff. Rousseff won and assumed office on January 1, 2011.

References

- ^ Levine, R.M., & Crocitti, J.J. (1999). The Brazil reader: History, culture, politics. p.11. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- ^ [1] Quem descobriu o Brasil?

- ^ COUTO, Jorge: A Construção do Brasil, Edições Cosmos, 2ª Ed., Lisboa, 1997.primeiro

- ^ Boxer, p. 98.

- ^ Boxer, p. 100.

- ^ Johns Hopkins University Press | Books | Slave Rebellion in Brazil

- ^ Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars Volume II: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900-2001. Potomac Books, 2003 ISBN 1574884522 Part 4; Chapter 5 - World War I and Brazil, 1917-18.

- ^ "The United States and Brazil: A Long Road of Unmet Expectations"; Monica Hisrt, Routledge 2004 ISBN 041595066X page 43

- ^ "The United States and Brazil: A Long Road of Unmet Expectations"; Monica Hisrt, Routledge 2004 ISBN 041595066X , Introduction: page xviii 3rd paragraph

- ^ Stepan, 1973.

- ^ "Anatomy of a coup d'etat; Brazil 1964"; Warren W. Van Pelt; Air War College, Air University (1967) ASIN B0007GYMM4

- ^ An excerpt of "Killing Hope" dealing with the Jango government

- ^ Brasil: Nunca Mais

- ^ [2] "Tais políticas - iniciadas com a abertura do governo Collor - foram continuadas por Fernando Henrique Cardoso e Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, segundo economistas e industriais ouvidos pela Folha"

- ^ Programa Nacional de Desestatização Template:Pt icon

- ^ Os efeitos da privatização sobre o desempenho econômico e financeiro das empresas privatizadas Template:Pt icon

- ^ Lula segue política econômica de FHC, diz diretor do FMI

- Template:Pt icon Fausto, Boris (2004). História do Brasil (History of Brazil). ISBN 8-531402-40-9 — Jabuti Prize in 1995.

- Braudel, Fernand, The Perspective of the World, Vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism, 1984, pp. 232–35.

External links

- Template:En icon Template:Pt icon Brazilink History - Links to sources of Brazilian history.

- Template:En icon Brazil - Article on Brazil from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Template:En icon History of Brazil - Offers a history of Brazil from 1500 to the present.

- Template:En icon Timeline Brazilian History - The most important dates in the history of Brazil from 1500 to the present.

- Template:Pt icon MeusEstudos.com: História do Brasil.

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA