Body hair: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

The thermodynamic properties of hair are based on the properties of the [[keratin]] strands and [[amino acids]] that combine into a 'coiled' structure. This structure lends to many of the properties of hair, such as its ability to stretch and return to its original length. It should be noted that this coiled structure does not predispose curly or frizzy hair, both of which are defined by oval or triangular [[hair follicle]] cross-sections.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hair-science.com/_int/_en/topic/topic_sousrub.aspx?tc=ROOT-HAIR-SCIENCE%5EAMAZINGLY-NATURAL%5ESHAPE-WORKSHOP&cur=SHAPE-WORKSHOP |title=Hair Shape |publisher=Hair-science.com |date=2005-02-01 |accessdate=2009-09-18}}</ref> |

The thermodynamic properties of hair are based on the properties of the [[keratin]] strands and [[amino acids]] that combine into a 'coiled' structure. This structure lends to many of the properties of hair, such as its ability to stretch and return to its original length. It should be noted that this coiled structure does not predispose curly or frizzy hair, both of which are defined by oval or triangular [[hair follicle]] cross-sections.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hair-science.com/_int/_en/topic/topic_sousrub.aspx?tc=ROOT-HAIR-SCIENCE%5EAMAZINGLY-NATURAL%5ESHAPE-WORKSHOP&cur=SHAPE-WORKSHOP |title=Hair Shape |publisher=Hair-science.com |date=2005-02-01 |accessdate=2009-09-18}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Malepuberty.jpg|thumb| |

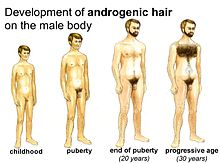

[[File:Malepuberty.jpg|thumb|Androgenic hair growth in a male human.]] |

||

Hair is a very good thermal conductor and aids both heat transfer into and out of the body. This is often seen as a problem with straighteners and blow drying as the hair quickly transfers the heat into the inner hair shaft and heats the water in the hair to boiling point resulting in dry brittle hair if silicone insulating oils are not used. When goose pimples are observed, small muscles contract to raise the hairs both to provide insulation, by reducing cooling by air convection of the skin, as well as in response to central nervous stimulus, similar to the feeling of 'hairs standing up on the back of your neck'. This phenomenon also occurs when static charge is built up and stored in the hair. Keratin however can easily be damaged by excessive heat and dryness, suggesting that extreme sun exposure, perhaps due to a lack of clothing, would result in perpetual hair destruction, eventually resulting in the genes being bred out in favor of high skin [[pigmentation]]. It is also true that parasites can live on and in hair thus peoples who preserved their body hair would have required greater general hygiene in order to prevent diseases caused by such as well as a need for grooming, two predominant factors in the civilization of homo sapiens.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hair-science.com/_int/_en/topic/topic_sousrub.aspx?tc=ROOT-HAIR-SCIENCE^SO-STURDY-SO-FRAGILE^PROPERTIES-OF-HAIR^STRONG-HAIR&cur=STRONG-HAIR |title=Properties Of Hair |publisher=Hair-science.com |date=2005-02-01 |accessdate=2009-09-18}}</ref> |

Hair is a very good thermal conductor and aids both heat transfer into and out of the body. This is often seen as a problem with straighteners and blow drying as the hair quickly transfers the heat into the inner hair shaft and heats the water in the hair to boiling point resulting in dry brittle hair if silicone insulating oils are not used. When goose pimples are observed, small muscles contract to raise the hairs both to provide insulation, by reducing cooling by air convection of the skin, as well as in response to central nervous stimulus, similar to the feeling of 'hairs standing up on the back of your neck'. This phenomenon also occurs when static charge is built up and stored in the hair. Keratin however can easily be damaged by excessive heat and dryness, suggesting that extreme sun exposure, perhaps due to a lack of clothing, would result in perpetual hair destruction, eventually resulting in the genes being bred out in favor of high skin [[pigmentation]]. It is also true that parasites can live on and in hair thus peoples who preserved their body hair would have required greater general hygiene in order to prevent diseases caused by such as well as a need for grooming, two predominant factors in the civilization of homo sapiens.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hair-science.com/_int/_en/topic/topic_sousrub.aspx?tc=ROOT-HAIR-SCIENCE^SO-STURDY-SO-FRAGILE^PROPERTIES-OF-HAIR^STRONG-HAIR&cur=STRONG-HAIR |title=Properties Of Hair |publisher=Hair-science.com |date=2005-02-01 |accessdate=2009-09-18}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:11, 7 October 2011

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

Androgenic hair, colloquially body hair, is the terminal hair that develops on the body during and after puberty. It is differentiated from the head hair and less visible vellus hair, which are much finer and lighter in color. The growth of androgenic hair is related to the level of androgens (male hormones) in the individual. Due to a normally higher level of androgen, men tend to have more androgenic hair than women.

From childhood onward, regardless of gender, vellus hair covers almost the entire area of the human body. Exceptions include the lips, the backs of the ears, the palms of hands, the soles of the feet, certain external genital areas, the navel and scar tissue. The density of hair – the number of hair follicles per area of skin – varies from person to person. In many cases, areas on the human body that contain vellus hair will begin to produce darker, thicker body hair. An example of this is the growth of an adolescent's beard on a once smooth chin.

Androgenic hair follows the same growth pattern as the hair that grows on the scalp, only the anagen phase is shorter, and the telogen phase is longer. While the anagen phase for the hair on one's head lasts for years, the androgenic hair growing phase lasts a few months.[1] The telogen phase for body hair lasts close to a year.[1] This shortened growing period and extended dormant period explains why the hair on the head tends to be much longer than other hair found on the body. Differences in length seen in comparing the hair on the back of the hand and pubic hair, for example, can be explained by varied growth cycles in those two regions. The same goes for differences in body hair length seen in different people, especially when comparing men and women.

Development and growth

Hair follicles are to varying degrees sensitive to androgen, primarily testosterone and its derivatives, with different areas on the body having different sensitivity. As androgen levels increase, the rate of hair growth and the weight of the hairs increase. Genetic factors determine both individual levels of androgen and the hair follicle's sensitivity to androgen, as well as other characteristics such as hair colour, type of hair and hair retention.

Rising levels of androgen during puberty cause vellus hair to transform into terminal hair over many areas of the body. The sequence of appearance of terminal hair reflects the level of androgen sensitivity, with pubic hair being the first to appear due to the area's especial sensitivity to androgen. The appearance of pubic hair in both sexes is usually seen as an indication of the start of a person's puberty. There is a sexual differentiation in the amount and distribution of androgenic hair, with men tending to have more terminal hair in more areas. This includes facial hair, chest hair, abdominal hair, leg and arm hair, and foot hair. Women retain more of the less visible vellus hair, although leg, arm, and foot hair can be noticeable on women. It is not unusual for women to have a few terminal hairs around their nipples as well.

Growth distribution

Like much of the hair on the human body, leg, arm, chest, and back hair begin as vellus hair. As people age, the hair in these regions will often begin to grow darker and more abundantly. This will typically happen during or after puberty. Men will generally have more abundant, coarser hair on the legs, arms, chest, and back, while women tend to have a less drastic change in the hair growth in these areas. However, some women will grow darker, longer hair in one or more of these regions.

Arms

Arm hair grows on a human's forearms, sometimes even on the elbow area. Terminal arm hair is concentrated on the wrist end of the forearm, extending over the hand. Terminal hair growth in adolescent and adult males is often much more intense than that in females, particularly for individuals with dark hair. In some cultures, it is common for women to remove arm hair, though this practice is less frequent than that of leg hair removal.

Terminal hair growth on arms is a secondary sexual characteristic in boys and appears in the last stages of puberty. Vellus arm hair is usually concentrated on the elbow end of the forearm and often ends on the lower part of the upper arm. This type of arm vellus hair growth sometimes occurs in young women and girls.

Feet

Visible hair appearing on the top surfaces of the feet and toes generally begins with the onset of puberty. Terminal hair growth on the feet is typically more intense in adult and adolescent males than in females.

Legs

Leg hair generally appears at the onset of adulthood, with the legs of men most often hairier than those of women. For a variety of reasons, people may shave their leg hair, including cultural practice or individual needs. Around the world, females generally shave their leg hair more regularly than men, to conform with the social norms of many cultures, many of which perceive smooth skin as a sign of youth and beauty. However, athletes of both sexes – swimmers, runners, cyclists and bodybuilders in particular – may shave their androgenic hair to reduce friction, highlight muscular development or to make it easier to get into and out of skin-tight clothing. The main reason why professional cyclists shave their legs is to make treatment of road rash less difficult.

Pubic

Pubic hair is a collection of coarse hair found in the pubic region. It will often also grow on the thighs and abdomen. Zoologist Desmond Morris disputes theories that it developed to signal sexual maturity or protect the skin from chafing during copulation, and prefers the explanation that pubic hair acts as a scent trap.[2]

The genital area of males and females are first inhabited by shorter, lighter vellus hairs that are next to invisible and only begin to develop into darker, thicker pubic hair at puberty. At this time, the pituitary gland secretes gonadotropin hormones which trigger the production of testosterone in the ovaries, respectively testicles promoting pubic hair growth. The average ages pubic hair begins to grow in males and females are 12 and 11, respectively.

Just as individual people differ in scalp hair color, they can also differ in pubic hair color. Differences in thickness, growth rate, and length are also evident.

Facial

Facial hair, as the name suggests, grows primarily on or around one's face. Both men and women experience facial hair growth, even though it is commonly accepted as a masculine trait. Like pubic hair, non-vellus facial hair will begin to grow in around puberty. Moustaches in young men usually begin to grow in at around the age of 13, although some men may not grow a moustache until they reach late teens.

Function

Androgenic hair provides tactile sensory input by transferring hair movement and vibration via the shaft to sensory nerves within the skin. Follicular nerves detect displacement of hair shafts and other nerve ending in the surrounding skin detect vibration and distortions of the skin around the follicles. Androgenic hair extends the sense of touch beyond the surface of the skin into the air and space surrounding it, detecting air movements as well as hair displacement from contact by insects or objects.[3][4]

Evolution

Determining the evolutionary function of androgenic hair must take into account both human evolution and the thermal properties of hair itself.

The thermodynamic properties of hair are based on the properties of the keratin strands and amino acids that combine into a 'coiled' structure. This structure lends to many of the properties of hair, such as its ability to stretch and return to its original length. It should be noted that this coiled structure does not predispose curly or frizzy hair, both of which are defined by oval or triangular hair follicle cross-sections.[5]

Hair is a very good thermal conductor and aids both heat transfer into and out of the body. This is often seen as a problem with straighteners and blow drying as the hair quickly transfers the heat into the inner hair shaft and heats the water in the hair to boiling point resulting in dry brittle hair if silicone insulating oils are not used. When goose pimples are observed, small muscles contract to raise the hairs both to provide insulation, by reducing cooling by air convection of the skin, as well as in response to central nervous stimulus, similar to the feeling of 'hairs standing up on the back of your neck'. This phenomenon also occurs when static charge is built up and stored in the hair. Keratin however can easily be damaged by excessive heat and dryness, suggesting that extreme sun exposure, perhaps due to a lack of clothing, would result in perpetual hair destruction, eventually resulting in the genes being bred out in favor of high skin pigmentation. It is also true that parasites can live on and in hair thus peoples who preserved their body hair would have required greater general hygiene in order to prevent diseases caused by such as well as a need for grooming, two predominant factors in the civilization of homo sapiens.[6]

Markus J. Rantala of the Department of Biological and Environmental Science, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, said humans evolved by "natural selection" to be hairless when the trade off of having "having fewer parasites" became more important than having a "warming, furry coat".[7]

Sexual selection

Cambridge University zoologist Charles Goodhart believed men have long preferred the "hairless trait" in women, ever since the existence of the "hairless trait" occurred in our hairy forebears 70,000-120,000 years ago during the last episode of global warming. Goodhart argued that humans are relatively hairless today compared to our ancestors because women who were sexually selected for their "hairless trait" passed it on to both their male and female offspring.[8]

Markus J. Rantala of the Department of Biological and Environmental Science, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, said the existence of "androgen dependent" hair on men "could be" explained by "sexual attraction" whereby hair on the genitals would trap "pheromones" and hair on the chin would make the chin appear "more massive".[7]

Across races

According to Ashley Montagu who taught anthropology at Princeton University, the "Mongoloid, "Bushmen" and "Negroid" are less hairy than the "Caucasoid" and Montagu said that the hairless feature is a neotenous trait.[9]

Rodney P.R. Dawber of the Oxford Hair Foundation and Clinical Lecturer in Dermatology said "Mongoloid males" have "little or no facial or body hair" and Dawber also said "Mediterranean males are covered with an exuberant pelage".[10]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b (Hair Growth: EMedicine Otolaryngology and Facial Plastic Surgery)

- ^ Morris, Desmond (1985). Bodywatching: a field guide to the human species. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 209.

- ^ "Controlled Stimulation of Hair Follicle Receptors - J.Sabah. J Appl Physiol.1974; 36: 256-257"http://jap.physiology.org/cgi/reprint/36/2/256.pdf

- ^ http://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/receptor.html

- ^ "Hair Shape". Hair-science.com. 2005-02-01. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ "Properties Of Hair". Hair-science.com. 2005-02-01. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ a b Rantala, M.J. (1999). Human nakedness: adaptation against ectoparasites? International Journal for Parasitology 29 1987±1989

- ^ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/zoologist-claims-sexual-preference-led-the-naked-ape-to-lose-its-hair-1581177.html

- ^ Montagu, Ashley. Growing Young. Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 1989 ISBN 0-89789-167-8

- ^ Dawber R.P.R. (1997). Diseases of the head and scalp (3rd ed.). Virginia:Blackwell Science Ltd.