South Bronx: Difference between revisions

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

The South Bronx is a place for working-class families. Its image as a poverty-ridden area developed in the latter part of the 20th century.<ref>http://www.lexisnexis.com/us/lnacademic/auth/checkbrowser.do?ipcounter=1&cookieState=0&rand=0.9697244443316492&bhcp=1</ref> There have been several factors contributing to the decay of the South Bronx: [[white flight]], [[landlord]] abandonment, changes in economic demographics abandonment, and also the construction of the [[Cross Bronx Expressway]].<ref name='Caro'/> |

The South Bronx is a place for working-class families. Its image as a poverty-ridden area developed in the latter part of the 20th century.<ref>http://www.lexisnexis.com/us/lnacademic/auth/checkbrowser.do?ipcounter=1&cookieState=0&rand=0.9697244443316492&bhcp=1</ref> There have been several factors contributing to the decay of the South Bronx: [[white flight]], [[landlord]] abandonment, changes in economic demographics abandonment, and also the construction of the [[Cross Bronx Expressway]].<ref name='Caro'/> |

||

The [[Cross Bronx Expressway]], completed in 1963, was a part of [[Robert Moses]]’s urban renewal project for New York City. The expressway is now known to have been a factor in the extreme urban decay seen by the borough in the 1970s and 1980s. Cutting |

The [[Cross Bronx Expressway]], completed in 1963, was a part of [[Robert Moses]]’s urban renewal project for New York City. The expressway is now known to have been a factor in the extreme urban decay seen by the borough in the 1970s and 1980s. Cutting through the heart of the South Bronx, the highway displaced thousands of residents from their homes, as well as several local businesses. The already poor and working-class neighborhoods were at another disadvantage: the decreased property value brought on by their proximity to the Cross Bronx Expressway. The neighborhood of [[East Tremont, Bronx|East Tremont]], in particular, was completely destroyed by the incursion of the expressway. The combination of increasing vacancy rates and decreased property values caused some neighborhoods to become considered undesirable by homeowners.<ref name='Caro'>{{cite book|authorlink=Robert Caro|last=Caro|first=Robert A.|title=[[The Power Broker|The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the fall of New York]]|location=New York|publisher=Knopf|year=1974|isbn=0-394-48076-7}}, p. 893-894</ref> |

||

In the late 1960s, the area's population began decreasing, commonly thought to be a result of new policies demanding that, for racial balance in schools, children be bused into other districts. Parents who worried about their children attending the demographically adjusted schools often relocated to the suburbs, where this was not a concern. In addition, [[rent control]] policies are thought to have contributed to the decline of many middle-class neighborhoods in the 1950s and 1960s; New York City's policies regarding rent control gave building owners no motivation to keep up their properties.<ref>[http://www.nycroads.com/roads/cross-bronx/ Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95, I-295 and US 1)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Therefore, desirable housing options were scarce, and vacancies further increased. In the late 1960s, by the time the city decided to consolidate welfare households in the South Bronx, its vacancy rate was already the highest of any place in the city.{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} |

In the late 1960s, the area's population began decreasing, commonly thought to be a result of new policies demanding that, for racial balance in schools, children be bused into other districts. Parents who worried about their children attending the demographically adjusted schools often relocated to the suburbs, where this was not a concern. In addition, [[rent control]] policies are thought to have contributed to the decline of many middle-class neighborhoods in the 1950s and 1960s; New York City's policies regarding rent control gave building owners no motivation to keep up their properties.<ref>[http://www.nycroads.com/roads/cross-bronx/ Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95, I-295 and US 1)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Therefore, desirable housing options were scarce, and vacancies further increased. In the late 1960s, by the time the city decided to consolidate welfare households in the South Bronx, its vacancy rate was already the highest of any place in the city.{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} |

||

Revision as of 06:11, 5 December 2013

The South Bronx is an area of the New York City borough of The Bronx, in the U.S. state of New York. The geographic definitions of the South Bronx have evolved and are disputed but certainly include the neighborhoods of Mott Haven and Melrose. The neighborhoods of Tremont, University Heights, Highbridge, Morrisania, Soundview, Hunts Point, Longwood and Castle Hill are sometimes considered part of the South Bronx.

The South Bronx is part of New York's 16th Congressional District, the poorest Congressional district in the United States. The South Bronx is served by the NYPD's 40th,[1] 41st,[2] 42nd,[3] 44th,[4] and 48th[5] Precincts. The South Bronx is also known worldwide as the place of birth of hip-hop culture.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

History

The South Bronx was originally called the Manor of Morrisania, and later Morrisania. It was the private domain of the powerful and aristocratic Morris family, which includes Lewis Morris, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Gouverneur Morris, penman of the United States Constitution. The Morris memorial is at St. Ann's Church of Morrisania. Morris' descendants own land in the South Bronx to this day.

As the Morrises developed their landholdings, an influx of German and Irish immigrants populated the area. Later, the Bronx was considered the "Jewish Borough," and at its peak in 1930 was 49% Jewish.[13] Jews in the South Bronx numbered 364,000 or 57.1% of the total population in the area.[14] The term was first coined in the 1940s by a group of social workers who identified the Bronx's first pocket of poverty, in the Port Morris section, the southernmost section of the Bronx.

1950s: Demographic shift

After World War II, as white flight accelerated and migration of ethnic and racial minorities continued, the South Bronx went from being two-thirds non-Hispanic white in 1950 to being two-thirds black or Puerto Rican in 1960.[15] Originally denoting only Mott Haven and Melrose, the South Bronx extended up to the Cross Bronx Expressway by the 1960s, encompassing Hunts Point, Morrisania, and Highbridge.

1960s: Start of decay

The South Bronx is a place for working-class families. Its image as a poverty-ridden area developed in the latter part of the 20th century.[16] There have been several factors contributing to the decay of the South Bronx: white flight, landlord abandonment, changes in economic demographics abandonment, and also the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway.[17]

The Cross Bronx Expressway, completed in 1963, was a part of Robert Moses’s urban renewal project for New York City. The expressway is now known to have been a factor in the extreme urban decay seen by the borough in the 1970s and 1980s. Cutting through the heart of the South Bronx, the highway displaced thousands of residents from their homes, as well as several local businesses. The already poor and working-class neighborhoods were at another disadvantage: the decreased property value brought on by their proximity to the Cross Bronx Expressway. The neighborhood of East Tremont, in particular, was completely destroyed by the incursion of the expressway. The combination of increasing vacancy rates and decreased property values caused some neighborhoods to become considered undesirable by homeowners.[17]

In the late 1960s, the area's population began decreasing, commonly thought to be a result of new policies demanding that, for racial balance in schools, children be bused into other districts. Parents who worried about their children attending the demographically adjusted schools often relocated to the suburbs, where this was not a concern. In addition, rent control policies are thought to have contributed to the decline of many middle-class neighborhoods in the 1950s and 1960s; New York City's policies regarding rent control gave building owners no motivation to keep up their properties.[18] Therefore, desirable housing options were scarce, and vacancies further increased. In the late 1960s, by the time the city decided to consolidate welfare households in the South Bronx, its vacancy rate was already the highest of any place in the city.[citation needed]

1970s: "The Bronx is burning"

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

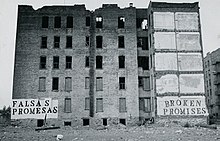

In the 1970s significant poverty reached as far north as Fordham Road. Around this time, the Bronx experienced some of its worst instances of urban decay. The media attention brought the South Bronx into common parlance nationwide.

The phrase "The Bronx is burning," attributed to Howard Cosell during a Yankees World Series game in 1977, refers to the arson epidemic caused by the total economic collapse of the South Bronx during the 1970s. During the game, as ABC switched to a generic helicopter shot of the exterior of Yankee Stadium, an uncontrolled fire could clearly be seen burning in the ravaged South Bronx surrounding the park.

The early 1970s saw South Bronx property values continue to plummet to record lows. A progressively vicious cycle began where large numbers of tenements and multistory, multifamily apartment buildings (left vacant by white flight) sat abandoned and unsalable for long periods of time, which, coupled with a stagnant economy and an extremely high unemployment rate, produced a strong attraction for criminal elements such as street gangs, which were exploding in number and beginning to support themselves with large-scale drug dealing in the area. Abandoned property also attracted large numbers of squatters such as the indigent, drug addicts and the mentally ill, who further lowered the borough's quality of living.

As the crisis deepened, the nearly bankrupt city government of Abraham Beame levied most of the blame on unreasonably high rents levied by white landlords, and began demanding they convert their rapidly emptying buildings into Section 8 housing, which paid a per capita stipend for low-income or indigent tenants from Federal HUD funds rather than from the cash-strapped city coffers. However, the HUD rate was not based on the property's actual value and was set so low by the city it left little opportunity or incentive for honest landlords to maintain or improve their buildings while still making a profit. HUD regulations also made it virtually impossible to evict tenants engaging in destructive or illegal behavior. The result was a disastrous acceleration of both the speed and northward spread of the cycle of decay in the South Bronx, as formerly desirable and well-maintained middle-to-upper class apartments in midtown (most notably along the Grand Concourse) were progressively vacated by white flight and either abandoned altogether or converted into Federally funded single room occupancy "welfare hotels" run by absentee slumlords to house predominantly single-parent Section 8 families and young, unemployed, recently immigrated Hispanic males.

The massive citywide spending cuts also left the few remaining building inspectors and fire marshals unable to enforce living standards or punish code violations. This encouraged slumlords and absentee landlords to neglect and ignore their property and allowed for gangs to set up protected enclaves and lay claim to entire buildings, which then spread crime and fear of crime to nearby unaffected apartments in a domino effect. Police statistics show that as the crime wave moved north across the Bronx, the remaining white tenants in the South Bronx (mostly elderly Jews) were preferentially targeted for violent crime by the influx of young, minority criminals because they were seen as easy prey; this became so common that the street slang terms "crib job" (referring to how elderly residents were as helpless as infants) and "push in" (meaning what would now be called a home invasion robbery) were coined specifically to describe them.[19]

Property owners who had waited too long to try to sell their buildings found that almost all of the property in the South Bronx had already been redlined by the banks and insurance companies. Unable to sell their property at any price and facing default on back property taxes and mortgages, landlords began to burn their buildings for their insurance value. A type of sophisticated white collar criminal known as a "fixer" sprung up during this period, specializing in a form of insurance fraud that began with buying out the property of redlined landlords at or below cost, then selling and reselling the buildings multiple times on paper between several different fictitious shell companies under the fixer's control, artificially driving up the value incrementally each time. Fraudulent "no questions asked" fire insurance policies would then be taken out on the overvalued buildings and the property stripped and burnt for the payoff. This scheme became so common that local gangs were hired by fixers for their expertise at the process of stripping buildings of wiring, plumbing, metal fixtures, and anything else of value and then effectively burning it down with gasoline. Many finishers became extremely rich buying properties from struggling landlords, artificially driving up the value, insuring them and then burning them; often the properties were still occupied by subsidized tenants or squatters at the time, who were given short or no warning before the building was burnt down and they were forced to move to another slum building, where the process would usually repeat itself. The rate of unsolved fatalities due to fire multiplied sevenfold in the South Bronx during the 1970s, with many residents reporting being burnt out of numerous apartment blocks one after the other.

Local South Bronx residents themselves also burned down vacant properties in their own neighborhoods. Much of this was reportedly done by those who had already worked stripping and burning buildings for pay: the ashes of burned down properties could be sifted for salable scrap metal. Other fires were caused by unsafe electrical wiring, fires set indoors for heating, and random vandalism associated with the general crime situation. Flawed HUD and city policies also encouraged local South Bronx residents to burn down their own buildings. Under the regulations, Section 8 tenants who were burned out of their current housing were granted immediate priority status for another apartment, potentially in a better part of the city. After the establishment of the (then) state-of-the-art Co-op City, there was a spike in fires as tenants began burning down their Section 8 housing in an attempt to jump to the front of the 2–3 year long waiting list for the new units.[19] HUD regulations also authorized lump-sum aid payments of up to $1000 to those who could prove they had lost property due to a fire in their Section 8 housing; although these payments were supposed to be investigated for fraud by a HUD employee before being signed off on, very little investigation was done and some HUD employees and social services workers were accused of turning a blind eye to suspicious fires or even advising tenants on the best way to take advantage of the HUD policies. On multiple occasions, firefighters were reported to have shown up to tenement fires only to find all the residents at an address waiting calmly with their possessions already on the curb.

By the time of Cosell's 1977 commentary, dozens of buildings were being burnt in the South Bronx every day, sometimes whole blocks at a time and usually far more than the fire department could keep up with, leaving the area perpetually blanketed in a pall of smoke. Firefighters from the period reported responding to as many as 7 fully involved structure fires in a single shift, too many to even bother returning to the station house between calls. The local police precincts—already struggling and failing to contain the massive wave of drug and gang crime invading the Bronx—had long since stopped bothering to investigate the fires, as there were simply too many to track. During this period, the NYPD's 41st Precinct Station House at 1086 Simpson Street became famously known as "Fort Apache, The Bronx" as it struggled to deal with the overwhelming surge of violent crime, which for the entirety of the 1970s (and part of the early 1980s) made South Bronx the murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault and arson capitals of America. By 1980, the 41st was renamed "The Little House on the Prairie", as fully 2/3 of the 94,000 residents originally served by the precinct had fled, leaving the fortified station house as one of the few structures in the neighborhood (and the sole building on Simpson Street) that had not been abandoned or burnt out.[20]

In total, over 40% of the South Bronx was burned or abandoned between 1970 and 1980, with 44 census tracts losing more than 50% and seven more than 97% of their buildings to arson, abandonment, or both.[21] The appearance was frequently compared to that of a bombed-out and evacuated European city following World War II.[22] On Oct. 5, 1977, President Jimmy Carter paid an unscheduled visit to Charlotte Street, while in New York to attend a conference at the United Nations. Charlotte Street at the time was a three-block devastated area of vacant lots and burned-out and abandoned buildings. The street had been so ravaged that part of it had been taken off official city maps in 1974. Carter instructed Patricia Roberts Harris, head of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, to take steps to salvage the area.[23]

The 1987 novel The Bonfire of the Vanities, by the American writer Tom Wolfe, presented the South Bronx as a nightmare world, not to be entered by middle-class whites.

Revitalization and current concerns

Beginning in the late 1980s, parts of the South Bronx started to experience urban renewal with rehabilitated and brand new residential structures, including both subsidized multifamily town homes and apartment buildings.[24] The Bright Temple A.M.E. Church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.[25]

On Charlotte Street, prefabricated ranch-style homes were built in the area in 1985, and the area had changed so significantly that the Bronx borough historian could not locate where Carter had stopped to survey the scene. As of 2004, homes on the street were worth up to a million dollars.[23] The Bronx County Courthouse has secured Landmark status, and efforts are underway to do the same for much of the Grand Concourse, in recognition of the area’s Art Deco architecture. In June 2010, the city Landmarks Preservation Commission gave consideration to establishment of a historic district on the Grand Concourse from 153rd to 167th Street. A final decision was expected in the coming months.[26]

Construction of the new Yankee Stadium has stirred controversy over plans which, along with the new billion dollar field, include new athletic fields, tennis courts, bicycle and walking paths, stores, restaurants as well as a new Metro-North Railroad station, which during baseball season might help ease overcrowding on the subway.[27]

There is hope that these developments also will help to generate residential construction.[citation needed] However, the new park comes at a price: a total of 22 acres (89,000 m2) in Macombs Dam and John Mullaly Parks were sacrificed to build it. In April of 2012, Heritage Field, a 50.8 million dollar ballpark, was built atop the grounds of the original Yankee Stadium.

The new stadium was completed in time for the start of the 2009 baseball season. However, the expected completion date of the promised athletic fields and other green space have yet to be revealed. Many in the local community oppose the stadium due to its effects on pollution, traffic, and a massive loss of the community's limited green space.[28]

The population of the South Bronx is currently increasing.[29][30] Strides have been made since the days of arson, the South Bronx is in a real recovery. Almost 50% of the population lives below the poverty line. Drug trafficking, gang activity, and prostitution are all still common throughout the South Bronx. Its precincts record high violent crime rates and are all NYPD "impact zones".

Arts and culture

Since the late 1970s the South Bronx has been home to a renewed grassroots art scene. The arts scene that sprouted at the Fashion Moda Gallery, founded by a Viennese artist, Stefan Eins, helped ignite the careers of artists like Keith Haring and Jenny Holzer, and 1980s break dancers like the Rock Steady Crew. It generated enough enthusiasm in the mainstream media for a short while to draw the art world's attention.[32]

Modern graffiti is prominent in the South Bronx, and is home to many of the fathers of graffiti art such as Tats Cru. The Bronx has a very strong graffiti scene despite the city's crackdown on illegal graffiti. The rise of hip-hop music, rap, breakdancing, and disc jockeying helped put the South Bronx on the musical map in the early 1980s. The South Bronx is now home to the Bronx Museum of the Arts on the Grand Concourse.[33]

Birthplace of Hip-hop

Hip hop is a broad conglomerate of artistic forms that originated as a specific street subculture within South Bronx communities during the 1970s in New York City.[7][8][9][10][11][12] Hip hop as music and culture formed during the 1970s when block parties became increasingly popular in New York City, particularly among African American youth residing in the Bronx.[35] Block parties incorporated DJs who played popular genres of music, especially funk and soul music. Due to the positive reception, DJs began isolating the percussive breaks of popular songs. This technique was then common in Jamaican dub music,[36] and was largely introduced into New York by immigrants from Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean, including DJ Kool Herc, who is generally considered the father of hip hop.

1520 Sedgwick Avenue is a 102-unit[37] apartment building in the Morris Heights neighborhood in The Bronx borough of New York City. Recognized as a long-time "haven for working-class families," in 2010 the New York Times reported that it is the "accepted birthplace of hip hop."[34] As hip hop grew from throughout the Bronx, 1520 was a starting point where Clive Campbell, later known as DJ Kool Herc, presided over parties in the community room at a pivotal point in the genre's history.[38][39] DJ Kool Herc is credited with helping to start hip hop and rap music at a house concert at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue on August 11, 1973.[40] At the concert he was DJing and emceeing in the recreation room of 1520 Sedgwick Avenue.[41] Sources have noted that while 1520 Sedgwick Avenue was not the actual birthplace of hip hop—the genre developed slowly in several places in the 1970s—it was verified to be the place where one of the pivotal and formative events occurred that spurred hip hop culture forward.[42] During a rally to save the building, DJ Kool Herc said, "1520 Sedgwick is the Bethlehem of Hip-Hop culture."[43]

On July 5, 2007, 1520 Sedgwick Avenue was recognized by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation as the "Birthplace of Hip-Hop."[44][45]

Education

The New York City Department of Education operates district public schools.

Community School Districts 7, 8, 9, and 12 are approximately within the South Bronx.[46]

Among the public schools are charter schools. Success Academies Bronx 1 and 2 and, opening in 2013, 3 are part of Success Academy Charter Schools. An elementary charter school, Academic Leadership Charter School, opened on 141st Street and Cypress Avenue.

Among the institutions of higher education, Hostos Community College of the City University of New York is located in Grand Concourse and 149th Street, ten blocks from Yankee Stadium.

The South Bronx is also home to both for-profit and nonprofit organizations that offer a range of professional training and other educational programs. Per Scholas, for example, is a nonprofit organization that offers free professional certification training directed towards successfully passing CompTIA A+ and Network+ certification exams as a route to securing jobs and building careers. Per Scholas also works with a growing number of Title One South Bronx middle schools, their students, and their families to provide computer training and access.

Transportation

Vehicular: Major Deegan Expressway (I-87); Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95); Bruckner Expressway (I-278); Sheridan Expressway (I-895); Triborough Bridge; Grand Concourse.

Mass transit: The 2, 4, 5, 6, B and D New York City Subway trains all travel through the South Bronx.

A South Bronx Greenway[47] is planned to connect south to Randalls Island and north along the Bronx River.

In 2000, 77.3% of all households in New York's 16th congressional district, covering the South Bronx, did not own automobiles, Citywide, the percentage is 55%.[48]

Notable natives

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

- Danny Aiello, born East Harlem raised on Bergen Ave

- Bobby Darrin, born & raised on Lincoln Ave

- Afrika Bambaataa, current resident of Soundview

- Rapper A.G. of the duo Showbiz and A.G., raised in Mott Haven

- Alex Ramos raised in The Bronx, Professional boxer

- Rapper Armageddon

- Al Pacino, raised in the South Bronx, born in East Harlem

- Aventura Dominican-American bachata music group, formed in The Bronx, New York

- Barry Wellman, raised in Fordham Road near Grand Concourse

- Harold Bloom, writer, literary critic, lived in the South Bronx

- Bernard McGuirk, grew up in the South Bronx

- Majora Carter, raised in, and resident of Hunts Point

- Colin Powell, raised in Hunts Point

- Rapper Cuban Link, born in Cuba, raised in the South Bronx

- Dolph Schayes, raised near East 180th Street and Grand Concourse

- Rapper Drag-On, raised in Soundview

- Rapper Fat Joe, raised in Morrisania

- Grandmaster Flash, current resident of Morrisania

- Harry Gibson

- Rapper Hell Rell, raised in Tremont

- Musician Jimi Hazel of 24-7 Spyz, raised in Mitchell Projects, Mott Haven

- Jennifer Lopez, raised in Castle Hill

- Hip hop pioneer DJ Kool Herc, raised in the Bronx and resides in 220th and Carpenter (Uptown Bronx)

- Rapper KRS-One, originally from Brooklyn, raised in both Mott Haven and Soundview

- Rapper Lord Tariq of the duo Lord Tariq and Peter Gunz, raised in Soundview

- Murray Perahia, concert pianist and conductor, grew up in Walton Avenue

- Charles Nelson Reilly actor, comedian, director and drama teacher, born in The Bronx.

- Rebel Diaz Rebel Diaz is a political hip hop trio out of the Bronx, New York and Chicago

- Ruben Diaz, Jr. Democratic Party politician

- Rapper Remy Ma, raised in Castle Hill

- Nine (rapper), rapper

- Rapper T La Rock Raised in the Bronx

- Scott La Rock Boogie Down Productions, born and raised in The Bronx

- Fr. Stan Fortuna, ordained as a priest in the Bronx in 1990.

- Tim Dog, rapper

- Tom Leykis, radio personality, from Sheridan Ave

- R&B singer Tony Sunshine, raised in Soundview

- Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Kerry Washington, actress, grew up on Jackson Avenue

- Willie Colón, salsa musician

- Big Pun, rapper, born and raised in Soundview

- French Montana, rapper, raised in Tremont

- Jordan Bratman, music marketer; born in the South Bronx

- Leonard Susskind, Theoretical Physicist

- Richard A. Muller physicist

- Kemba Walker, NBA Player, raised in Soundview

Mentions in popular culture

Movies

- 1990: The Bronx Warriors, 1982

- Gloria, 1980

- Willie Dynamite, 1974

- Fort Apache, The Bronx, 1981

- Wolfen (film), 1981

- Wild Style, 1983

- Beat Street, 1984

- South Bronx Heroes, 1985

Music

Television

- SPEED TV's Hard Parts: South Bronx features BS&F Auto Parts store located in the area dealing with automobile parts.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ 40th Precinct, NYPD.

- ^ 41st Precinct, NYPD.

- ^ 42nd Precinct, NYPD.

- ^ 44th Precinct, NYPD.

- ^ 48th Precinct, NYPD.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (12 February 2006). "A Rolling Shout-Out to Hip-Hop History". The New York Times. p. 32. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ a b Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-30143-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Castillo-Garstow, Melissa (1). "Latinos in Hip Hop to Reggaeton". Latin Beat Magazine. 15 (2): 24(4).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rojas, Sal (2007). "Estados Unidos Latin Lingo". Zona de Obras (47). Zaragoza, Spain: 68.

- ^ a b Allatson, Paul. Key Terms in Latino/a Cultural and Literary Studies. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, 2007, 199.

- ^ a b Schloss, Joseph G. Foundation: B-boys, B-girls and Hip-Hop Culture in New York. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, 125.

- ^ a b From Mambo to Hip Hop. Dir. Henry Chalfant. Thirteen / WNET, 2006, film

- ^ :: Bronx County Clerks Office ::

- ^ Bronx Synagogues - Historical Survey

- ^ Tarver, Denton (2007). "The New Bronx; A Quick History of the Iconic Borough". The Cooperator. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.lexisnexis.com/us/lnacademic/auth/checkbrowser.do?ipcounter=1&cookieState=0&rand=0.9697244443316492&bhcp=1

- ^ a b Caro, Robert A. (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-48076-7., p. 893-894

- ^ Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95, I-295 and US 1)

- ^ a b Rooney, Jim (1995). Organizing the South Bronx. SUNY Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-7914-2210-0. Cite error: The named reference "Rooney" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fisher, Ian (23 June 1993). "Pulling Out of Fort Apache, the Bronx; New 41st Precinct Station House Leaves Behind Symbol of Community's Past Troubles". New York Times. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ Flood, Joe (16 May 2010). "Why the Bronx burned". The New York Post. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ http://www.demographia.com/db-sbrx-txt.htm

- ^ a b Fernandez, Manny (5 October 2007). "In the Bronx, Blight Gave Way to Renewal". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Wynn, Terry (17 January 2005). "South Bronx rises out of the ashes". NBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 13 March 2009.

- ^ Dolnick, Sam (22 June 2010). "As Concourse Regains Luster, City Notices". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ http://proquest.umi.com/pqdlink?Ver=1&Exp=12-17-2012&FMT=7&DID=1274048301&RQT=309

- ^ New Yankee stadium

- ^ The (South) Bronx is up: a neighborhood revives"

- ^ SOUTH BRONX RESURRECTION 27 May 2004

- ^ 2007 Fort Greene Park Summer Literary Festival website. See also the Flickr.com photograph album of the 2007 Festival

- ^ Siegal, Nina (27 December 2000). "Hope Is Artists' Medium In a Bronx Neighborhood; Dancers, Painters and Sculptors Head to Hunts Point". New York Times. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ http://www.bronxmuseum.org/ Bronx Museum website

- ^ a b Borgya, A. (September 3, 2010) "A Museum Quest Spins On and On", New York Times. Retrieved 9/4/10.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric, 2007, Know What I Mean? : Reflections on Hip-Hop, Basic Civitas Books, p. 6.

- ^ Stas Bekman: stas (at) stason.org. "What is "Dub" music anyway? (Reggae)". Stason.org. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ (January 10, 2010) "Hip-hop landmark falls on hard times", Retrieved 9/4/10.

- ^ David Gonzalez, "Will Gentrification Spoil the Birthplace of Hip-Hop?", The New York Times, May 21, 2007, retrieved on July 1, 2008

- ^ Jennifer Lee, "Tenants Might Buy the Birthplace of Hip-Hop", The New York Times, January 15, 2008, retrieved on July 1, 2008

- ^ Chang, Jeff. Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. St. Martin's Press, New York: 2005. ISBN 978-0-312-42579-1. pp. 68–72

- ^ Tukufu Zuberi ("detective"), BIRTHPLACE OF HIP HOP, History Detectives, Season 6, Episode 11, New York City, found at PBS official website. Accessed February 24, 2009.

- ^ Tukufu Zuberi ("detective"), Birthplace of Hip Hop, History Detectives, Season 6, Episode 11, New York City. PBS. Retrieved 9/3/10.

- ^ (July 18, 2007) "1520 Sedgwick Avenue to be Recognized as Official Birthplace of Hip-Hop", Retrieved 9/3/10.

- ^ (July 23, 2007) "An Effort to Honor the Birthplace of Hip-Hop", New York Times. Retrieved 9/3/10.

- ^ (July 23, 2007) "1520 Sedgwick Avenue Honored as a Hip-Hop Landmark Today", XXL Magazine. Retrieved 9/3/10.

- ^ To locate a school, see N.Y.C. Department of Education, Find a School (scroll down), as accessed Jun. 1, 2010.

- ^ NYC Economic Development Corp South Bronx Greenway

- ^ "Fact Sheet, Rep. Jose E. Serrano" (PDF). Retrieved 9 April 2011.

Further reading

- Kozol, Jonathan (1995); Amazing Grace; Crown Publishers.

- Berman, Marshall; Berger, Brian, eds. (2007). New York Calling: From Blackout to Bloomberg. Reaktion Books.

- Berman, Marshall (1988). All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. Penguin.

- Gonzalez, Evelyn (2006). The Bronx (Columbia History of Urban Life). Columbia University Press.

- Jensen, Robert, ed. (1979). Devastation/resurrection: the South Bronx. New York: Bronx Museum of the Arts.

- Jonnes, Jill (2002). South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of an American City. Fordham University Press.

- Office of the Borough President (Bronx, New York City) (1990). Strategic policy statement. New York: Office of the Bronx Borough President.

- Twomey, Bill (2007). The Bronx, in bits and pieces. Bloomington, IN: Rooftop Publishing.

Pictorial works

- Kahane, Lisa (2008). Do Not Give Way To Evil: Photographs of the South Bronx, 1979-1987 (Miss Rosen ed.).

- Twomey, Bill (2002). South Bronx. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. (Pictorial work on historical social life and customs in the South Bronx)