Digambara: Difference between revisions

→External links: Cleanup Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Links Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

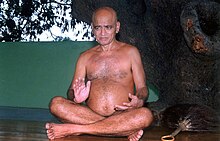

'''Digambara''' ({{IPAc-en|d|ɪ|ˈ|g|ʌ|m|b|ə|r|ə}}; [[Sanskrit]] "sky-clad") is [[Jain schools and branches|a school of Jainism]], which distinguished itself from the white-clad [[Śvētāmbara]] in about the third century.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=23}}</ref> Monks in the Digambara tradition don't wear any clothes, as it is considered ''parigraha'' (possession). They carry only a broom made up of fallen peacock feathers (to follow the principle of [[Ahimsa in Jainism|Ahiṃsā]]) and a water gourd.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=316}}</ref> |

'''Digambara''' ({{IPAc-en|d|ɪ|ˈ|g|ʌ|m|b|ə|r|ə}}; [[Sanskrit]] "sky-clad") is [[Jain schools and branches|a school of Jainism]], which distinguished itself from the white-clad [[Śvētāmbara]] in about the third century.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=23}}</ref> Monks in the Digambara tradition don't wear any clothes, as it is considered ''parigraha'' (possession). They carry only a broom made up of fallen peacock feathers (to follow the principle of [[Ahimsa in Jainism|Ahiṃsā]]) and a water gourd.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=316}}</ref> |

||

The Digambara sect of Jainism rejects the authority of the [[Jain Agamas]] compiled by [[Sthulabhadra]].<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=444}}</ref> They believe that by the time of Dharasena, the twenty-third teacher after [[Indrabhuti Gautama]], knowledge of only one |

The Digambara sect of Jainism rejects the authority of the [[Jain Agamas]] compiled by [[Sthulabhadra]].<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=444}}</ref> They believe that by the time of Dharasena, the twenty-third teacher after [[Indrabhuti Gautama]], knowledge of only one Anga was there. This was about 683 years after the [[Moksha (Jainism)|Nirvana]] of [[Mahavira]]. After Dharasena's pupils Pushpadanta and Bhutabali, even that was lost.{{sfn|Dundas|2002|p=79}} |

||

According to Digambara tradition, Mahavira, the last ''[[tirthankara]]'', never married. He renounced the world at the age of thirty after taking permission of his parents.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=313}}</ref> The Digambara believe that after attaining [[Kevala Jnana]], omniscient beings or [[Arihant (Jainism)|arihant]] are free from human needs like hunger, thirst, and sleep.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=314}}</ref> One of the most important scholar-monks of Digambara tradition was [[Kundakunda]]. He authored [[Prakrit]] texts such as the ''[[Samayasāra]]'' and the ''Pravacanasāra''. Samantabhadra and [[Siddhasena Divakara]] were other important monks of this tradition.{{sfn|Singh|2008|p=524}} |

According to Digambara tradition, Mahavira, the last ''[[tirthankara]]'', never married. He renounced the world at the age of thirty after taking permission of his parents.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=313}}</ref> The Digambara believe that after attaining [[Kevala Jnana]], omniscient beings or [[Arihant (Jainism)|arihant]] are free from human needs like hunger, thirst, and sleep.<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|2008|p=314}}</ref> One of the most important scholar-monks of Digambara tradition was [[Kundakunda]]. He authored [[Prakrit]] texts such as the ''[[Samayasāra]]'' and the ''Pravacanasāra''. Samantabhadra and [[Siddhasena Divakara]] were other important monks of this tradition.{{sfn|Singh|2008|p=524}} |

||

Revision as of 06:39, 26 September 2015

Digambara (/dɪˈɡʌmbərə/; Sanskrit "sky-clad") is a school of Jainism, which distinguished itself from the white-clad Śvētāmbara in about the third century.[1] Monks in the Digambara tradition don't wear any clothes, as it is considered parigraha (possession). They carry only a broom made up of fallen peacock feathers (to follow the principle of Ahiṃsā) and a water gourd.[2]

The Digambara sect of Jainism rejects the authority of the Jain Agamas compiled by Sthulabhadra.[3] They believe that by the time of Dharasena, the twenty-third teacher after Indrabhuti Gautama, knowledge of only one Anga was there. This was about 683 years after the Nirvana of Mahavira. After Dharasena's pupils Pushpadanta and Bhutabali, even that was lost.[4]

According to Digambara tradition, Mahavira, the last tirthankara, never married. He renounced the world at the age of thirty after taking permission of his parents.[5] The Digambara believe that after attaining Kevala Jnana, omniscient beings or arihant are free from human needs like hunger, thirst, and sleep.[6] One of the most important scholar-monks of Digambara tradition was Kundakunda. He authored Prakrit texts such as the Samayasāra and the Pravacanasāra. Samantabhadra and Siddhasena Divakara were other important monks of this tradition.[7]

The Satkhandagama and Kasayapahuda have major significance in the Digambara tradition.[8]

Monasticism

In words of Heinrich Zimmer,[9] digambara means -

those whose, garment (ambara) is the element that fills the four quarters of space (dig- directions)

Every Digambara monk is required to follow 28 vows (vrats) compulsory.

- Five great vows (Maha-vrat)

- Ahiṃsā - Not to hurt any living being by actions and thoughts.

- Satya - Not to lie in any circumstances.

- Asteya - Not to take anything if not given.

- Brahmacharya - Celibacy in action, words & thoughts.[10]

- Aparigraha (Non-possession)- Complete detachment from material property.

- Fivefold regulation of activities (samiti)[11]

- Control of speech - Not to criticise anyone.

- Control of thought

- Regulation of movement - To prevent killing of small living beings.

- Care in lifting things

- Examining food and drink before consuming.[12][13]

- Six Essential Duties[14]

- Sämäyika - Equanimity towards every living being

- Devapujä - To worship qualities of 24 Tirthankaras

- Vandanä - To bow down to the Arihants, Siddhas and Acharyas

- Pratyakhyan- Renunciation

- Pratikramana- Repentance

- Kayotsarga- Giving up attachment to the body (Posture: rigid and immobile, with arms held stiffly down, knees straight, and toes directly forward)[9]

- Strict Control on five senses[15]

- Not to use tooth powder to clean teeth

- To take rest only on earth or wooden pallet.

- Not to take bath

- Eat food in standing posture (ahara)

- To consume food & water once in a day

- To pull out hair by hand (Kesh-loch)

- To be nude (digambara)

Famous monks

| Acharyas | Time period | Known for |

|---|---|---|

| Bhadrabahu | 3rd century BC | Chandragupta Maurya's spiritual teacher |

| Kundakunda | 2nd century AD | Author of Samayasāra, Niyamasara, Pravachansara, Barah anuvekkha |

| Umaswami | 2nd century AD | Author of Tattvartha Sutra (canon on science and ethics) |

| Pujyapada | 5th century AD | Author of Iṣṭopadeśa (Divine Sermons), a concise work of 51 verses |

| Manatunga | 6th century AD | Creator of famous Bhaktamara Stotra |

| Virasena | 8th-century AD | Mathematician and author of Dhavala |

| Jinasena | 9th century AD | Author of Mahapurana (major Jain text) and Harivamsha Purana. |

| Nemichandra | 10th century AD | Author of Dravyasamgraha and supervised the consecration of the Gomateshwara statue. |

| Shantisagar | 20th century AD | Reformer of digambara tradition. |

The prominent Acharyas of the Digambar tradition were Kundakunda (author of Samayasar and other works),[16] Virasena (author of a commentary on the Dhavala).[17] Siribhoovalaya, a cryptographic work by digambara monk, Kumudendu Muni is still being deciphered.

In the 10th century, Digambar tradition was divided into two main orders.

- Mula Sangh, which includes Sena gana, Deshiya gana and Balatkara gana traditions

- Kashtha Sangh, which includes the Mathura gana and Lat-vagad gana traditions

Shantisagar, belonged to the tradition of Sena gana. Practically all the Digambara monks today belong to his tradition, either directly or indirectly. The Bhattarakas of Shravanabelagola and Mudbidri belong to Deshiya gana and the Bhattaraka of Humbaj belongs to the Balatkara gana.[18]

Historicity

Indus valley

Relics found from Harrapan excavations like seals depicting 'Kayotsarga' posture, idols in Padmasana and a nude bust of red limestone[19] give insight about the antiquity of the Digambara tradition.

In Literature

The presence of gymnosophists ("naked philosophers") in Greek records as early as the fourth century B.C., supports the claim of the Digambaras that they have preserved the ancient Sramāna practice.[9]

In Majjhima Nikaya, Buddha tells "Thus far, SariPutta, did I go in my penance? I went without clothes. I licked my food from my hands. I took no food that was brought or meant especially for me. I accepted no invitation to a meal."[20] These being in conformity with the conduct of a digambara monk, it is possible that Buddha started his ascetic life as a digambara.[21]

See also

- Nudity in religion

- God in Jainism

- Kshullak

- Jain Philosophy

- Timeline of Jainism

- Digambar Jain Mahasabha

Notes

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 23

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 316

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 444

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 313

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 314

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 524.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 63-64.

- ^ a b c Zimmer 1953, p. 210.

- ^ Shah, Pravin. "Five Great Vows (Maha-vratas) of Jainism". Jainism Literature Center, Harvard University Archives (2009)

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 144.

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 93–96.

- ^ Pramansagar 2008, p. 189-191.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 143.

- ^ http://www.digambarjainonline.com/dharma/mahagun.htm

- ^ Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women - Padmanabh S. Jaini - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- ^ Satkhandagama : Dhaval (Jivasthana) Satparupana-I (Enunciation of Existence-I) An English Translation of Part 1 of the Dhavala Commentary on the Satkhandagama of Acarya Pushpadanta & Bhutabali Dhavala commentary by Acarya Virasena English tr. by Prof. Nandlal Jain, Ed. by Prof. Ashok Jain ISBN 9788186957479

- ^ Jaina Community: A Social Survey - Vilas Adinath Sangave - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 111. ISBN 9780759101722. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Pruthi, R.K. (2004). Buddhism and Indian Civilization. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 197–203. ISBN 978-81-71418664. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~pluralsm/affiliates/jainism/article/antiquity.htm

References

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A History Of Ancient And Early Medieval India: From The Stone Age To The 12Th Century, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Dundas, Paul (2002), Jains, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26606-2

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Tattvârthsûtra (1st ed.), (Uttarakhand) India: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-2-1,

Non-Copyright

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953), Joseph Campbell (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-8120807396

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Pramansagar, Muni (2008), jain tattvavidya, India: Bhartiya Gyanpeeth, ISBN 978-81-263-1480-5

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-4-8, archived from the original on 2012,

Non-Copyright

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help)