Islam: Difference between revisions

| Line 191: | Line 191: | ||

==Controversies and criticisms== |

==Controversies and criticisms== |

||

{{Disputed-section}} |

|||

{{main|Criticism of Islam}} |

{{main|Criticism of Islam}} |

||

<!-- This is a debated topic, so don't change this part in a major way without first discussing it on the talk page --> |

|||

<!-- Remember, this should only be a summary; the full article should remain at Criticism of Islam. --> |

|||

Islam has been the subject of criticism and controversy from the very start, and is often viewed with considerable negativity in the West when compared to other religions. <ref> Ernst, Carl (2002). Rethinking Muhammad in the Contemporary World) p. 11 </ref> Islam, the Qur'an, and Muhammad, have all been subject to both criticism and vilification. <ref> Ernst, Carl (2002). Rethinking Muhammad in the Contemporary World) p. 11 </ref> |

Islam has been the subject of criticism and controversy from the very start, and is often viewed with considerable negativity in the West when compared to other religions. <ref> Ernst, Carl (2002). Rethinking Muhammad in the Contemporary World) p. 11 </ref> Islam, the Qur'an, and Muhammad, have all been subject to both criticism and vilification. <ref> Ernst, Carl (2002). Rethinking Muhammad in the Contemporary World) p. 11 </ref> |

||

The main points of [[Secularism|secular]] criticism are: |

|||

Criticism of Islam has also come about due to apparent intolerances committed by some Muslims through the use of religious edicts or [[fatwas]].{{fact}} Cases such as the death edict declared by [[Ayatollah Khomeini]] against British writer [[Salman Rushdie]] and the human rights abuses committed by the Taliban while they were in power, are few of the many cases that had generated controversy and criticism regarding the religion of Islam. Recent events such as the use of violence by [[Islamism|Islamist]] militant organizations have caused many to raise questions regarding Islamic views on war and violence, particularly as a means of spreading Islam.{{fact}} |

|||

*The use of [[fatwas]] to punish violations committed by Muslims (e.g. the death edict against British writer [[Salman Rushdie]]). <ref>[[fatwas|Wikipedia: Fatwas]]</ref>,<ref>[[List of well-known fatwas|Wikipedia: List of well-known fatwas]]</ref> |

|||

*Human rights abuses by the Taliban and other fundamentalist governments. <ref>[[Taliban Movement|Wikipedia: Taliban Movement]]</ref>, <ref>[http://www.dhimmitude.org/archive/universal_islam.html Universal Human Rights and Human Rights in Islam] by David Littman</ref> |

|||

*The use of violence by [[Islamism|Islamist]] militant organizations as a means of spreading Islam. <ref>[http://www.geocities.com/martinkramerorg/Terms.htm Coming to Terms: Fundamentalists or Islamists?] by Martin Kramer </ref>, <ref>[[Islamic fundamentalism|Wikipedia: Islamic fundamentalism]]</ref> |

|||

*The state of women's rights in muslim societies. <ref>[http://www.mwlusa.org/ Muslim Women's League]</ref>, <ref>[[Sharia#Domestic_punishments|Wikipedia: Sharia - Domestic Punishment]]</ref> |

|||

*The suppression of free speech (e.g. [[Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy|Muhammad Cartoons]]). <ref>[[International reactions to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy|Wikipedia: International reactions to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy]]</ref>, <ref>[http://www.masud.co.uk/ISLAM/misc/alshifa/pt4ch1sec2.htm The proof of the necessity of killing anyone who curses the Prophet or finds fault with him] masud.co.uk</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 19:26, 23 August 2006

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Islam (Arabic: ) is a monotheistic religion based upon the Qur'an, which adherents believe was sent by God (Arabic: [[Allah|Template:ArabDIN]]) through Muhammad. Followers of Islam, known as Muslims (Arabic: Template:Ar), believe Muhammad to have been God's final prophet; most of them see the historic record of the actions and teachings of the Prophet Muhammad related in the Hadith and Sunnah as indispensable tools for interpreting the Qur'an.

Like Judaism and Christianity, Islam is considered an Abrahamic religion.[1] With a total of approximately 1.4 billion adherents[2], Islam is the second-largest religion in the world and claims to be the world's fastest growing religion. The majority of Muslims are not Arabs (in fact only 20 percent of Muslims originate from Arab countries). [3] At current rates, Islam will soon become the second largest religion in the United States, [4] and it is already the second largest faith in the UK.

Secular historians place Islam's beginnings during the late 7th century in Arabia. Under the leadership of Muhammad and his successors, Islam rapidly spread by religious conversion and military conquest.[5] Today, followers of Islam may be found throughout the world, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Etymology

In Arabic, Islam derives from the triconsonantal root Sīn-Lām-Mīm, with a basic meaning of "to surrender". Islam is an abstract nominal derived from this root, and literally means "submission to 'The God' (Arabic:Allah)". The legislative meaning is to submit to God by singling Him out in all acts of worship, to yield obediently to Him and to free and disassociate oneself from Polytheism and its people. Other Arabic words derived from the same root include:

- Islam, is also derived from the arabic word "Salaam" which means peace.

- Salaam, the word salaam literally translates to freedom from all harm. That is why one of the names of Paradise is As-Salam, because therein there is no harm. Therefore the common salutation, assalamu alaikum ("may you be free from all harm").

- Muslim, a muslim is a person who other people "salimou" ,(i.e. were left unharmed/assulted, left at peace) from his toungue and hands (i.e. no physical or verbal harrasment).

- Muslim, an agentive noun meaning "one who submits wholeheartedly [to God]".

- Salamah, meaning "safety", also used in the common farewell ma' as-salamah ("[go] with safety").

- Aslam (with a short "a" vowel) also means "I submit", since the addition of a hamza to the beginning of the triliteral root, followed by the first two consonants, a short vowel, and the final consonant, is the first-person singular imperfect tense in Arabic. (For example, from Sĩn-Kãf-Nũn, the word "'askun" means "I live" [reside].)

Beliefs

Muslims believe that God revealed his direct word for humanity to Muhammad (c. 570–632) through the angel Gabriel and earlier prophets, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. Muslims believe that Muhammad is the last prophet, based on the Qur'anic phrase "Seal of the Prophets" and sayings of the prophet of Islam himself, and that his teachings for humanity will last until the Day of the Resurrection. Muslims assert that the main written record of revelation to humanity is the Qur'an, which is flawless, immutable, and which Muslims believe is the final revelation of God to humanity.

Muslims hold that Islam is the same belief as that of all the messengers sent by God to humanity since Adam, with the Qur'an, the text used by all sects of the Muslim faith, codifying the final revelation of God. Islamic texts depict Judaism and Christianity as prophetic successor traditions to the teachings of Abraham. The Qur'an calls Jews and Christians "People of the Book", and distinguishes them from "Polytheists". However, Muslims believe that some people have distorted the word of God by deliberately altering words in meaning, form and placement in their respective holy texts, such as Jews changing the Torah and Christians the Injeel. This perceived distortion is known as tahrif, or tabdīl, meaning "alteration, substitution". This doctrine is accepted by most Muslims; some relatively small sects, such as Mu'tazili and Ismaili, as well as a few Islamic scholars and some members of various liberal movements within Islam, reject the view that the Qur'an is a correction of Jewish and Christian scriptures.[citation needed]

However, some Muslims believe that Islam also emphasises compassion as well as the pursuit of justice, equality, and knowledge are equally important as belief in Allah, the Qur'an, etc.

Fundamental practices

Shahadah

The basic creed or tenet of Islam is found in the shahādatān ("two testimonies"): Template:ArabDIN — "I testify that there is no god but The God (Arabic:Allah) and I testify that Muhammad is the Messenger of God."[6] As the most important pillar, this testament can be considered a foundation for all other beliefs and practices in Islam. Children are taught to recite and understand the shahadah as soon as they are able to do so. Muslims repeat the shahadah in prayer, and non-Muslims use the creed to formally convert to Islam.[7]

Salat

Muslims perform five daily prayers throughout the day as a form of submission to God. The ritual combines specific movements and spiritual aspects, preceded by wudu', or ablution. It is also supposed to serve as a reminder to do good and strive for greater causes,[8] as well as a form of restraint from committing harmful or shameful deeds.

It is believed that the prayer ritual was demonstrated to Muhammed by the angel Jabrīl, or Gabriel in English.

Zakat

Zakat, or alms-giving, is a mandated giving of charity to the poor and needy by able Muslims based on the wealth that he or she has accumulated. It is a personal responsibility intended to ease economic hardship for others and eliminate inequality.[9]

Sawm

Sawm, or fasting, is an obligatory act during the month of Ramadan. Muslims must abstain from food, drink, and sexual intercourse from dawn to dusk and are to be especially mindful of other sins that are prohibited. This activity is intended to allow Muslims to seek nearness to God as well as remind them of the needy.[10]

Hajj

The Hajj is a pilgrimage that occurs during the month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the city of Mecca. The pilgrimage is required for all Muslims who are both physically and financially able to go and is to be done at least once in one's lifetime.[11]

God

The fundamental concept in Islam is the Oneness of God (tawhid), monotheism which is absolute, not relative or pluralistic. God is described in Sura al-Ikhlas, as follows:

- "Say: He is God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him." [Quran 112:1]

In Arabic, God is called Allāh. The word is etymologically connected to ʾilāh "deity", Allāh is also the word used by Christian and Jewish Arabs, translating ho theos of the New Testament and Septuagint; it predates Muhammad and in its origin does not specify a "God" different from the one worshipped by Judaism and Christianity, the other Abrahamic religions. A common misconception is that "Allah" is a different deity from "God," however that is untrue. Allah merely means God in Arabic and Muslims, Christians, and Jews all worship the same God, though they hold different concepts about Him.

The name "Allah" shows no plural or gender. In Islam "Allah" Almighty as the Qur’an says:

- "(He is) the Creator of the heavens and the earth: He has made for you pairs from among yourselves, and pairs among cattle: by this means does He multiply you: there is nothing whatever like unto Him, and He is the One that hears and sees (all things)." [Quran 42:11].

The implicit usage of the definite article in Allah linguistically indicates the divine unity. Muslims believe that the God they worship is the same God of Abraham. Muslims reject the Christian doctrine concerning the trinity of God, seeing it as akin to polytheism. Quoting from the Qur'an, sura An-Nisa:

- "O People of the Book! Commit no excesses in your religion: Nor say of God aught but the truth. Jesus Christ, the son of Mary, was (no more than) a messenger of God, and His Word, which He bestowed on Mary, and a spirit proceeding from Him: so believe in God and His messengers. Say not "Trinity": desist: it will be better for you: for God is one God: Glory be to Him: (far exalted is He) above having a son. To Him belong all things in the heavens and on earth. And enough is God as a Disposer of affairs." [Quran 4:171]

No Muslim visual images or depictions of God are meant to exist because such artistic depictions may lead to idolatry and are thus disdained. Moreover, most Muslims believe that God is incorporeal, making any two- or three- dimensional depictions impossible. Such aniconism can also be found in Jewish and some Christian theology. Instead, Muslims describe God by the names and attributes that he revealed to his creation. All but one Sura (chapter) of the Qur'an begins with the phrase "In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful".

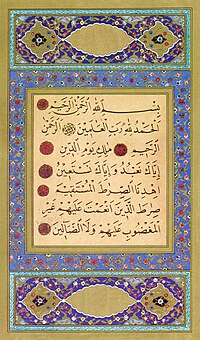

The Qur'an

The Qur'an is considered by Muslims to be the literal, undistorted word of God, and is the central religious text of Islam. It has also been called, in English, "the Koran" and (archaically) "the Alcoran." Qur'an is the currently preferred English transliteration of the Arabic original (قرآن); it means “recitation”. Although the Qur'an is referred to as a "book", when a Muslim refers to the Qur'an, they are referring to the actual text, the words, rather than the printed work itself.

Muslims believe that the Qur'an was revealed to the prophet Muhammad by God through the Angel Gabriel on numerous occasions between the years 610 and up till his death in 632. In addition to memorizing his revelations, his followers had written them down on parchments, stones, and leaves, to preserve the revelation.

Most Muslims regard paper copies of the Qur'an with veneration, washing as for prayers before reading the Qur'an. Old Qur'ans are not destroyed as wastepaper, but burned.

Most Muslims memorize at least some portion of the Qur'an in the original language (i.e. Arabic). Those who have memorized the entire Qur'an are known as hafiz (plural huffaz).

Muslims believe that the Qur'an is perfect only as revealed in the original Arabic. Translations were the result of human effort, the differences in human languages, and human fallibility, as well as lacking the inspired verses believers find in the Qur'an. Translations are therefore only commentaries on the Qur'an, or "interpretations of its meaning", not the Qur'an itself. Many modern, printed versions of the Qur'an feature the Arabic text on one page, and a vernacular translation on the facing page.

Organization

Islamic law

The Sharia (Arabic for "well-trodden path") is Islamic law, as shown by traditional Islamic scholarship. The Qur'an is the foremost source of Islamic jurisprudence. The second source is the sunnah of Muhammad and the early Muslim community. The sunnah is not itself a text like the Qur'an, but is extracted by analysis of the hadith (Arabic for report), which contain narrations of Muhammad's sayings, deeds, and actions. Ijma (consensus of the community of Muslims) and qiyas (analogical reasoning) are the third and fourth sources of Sharia.

Islamic law covers all aspects of life, from the broad topics of governance and foreign relations all the way down to issues of daily living. Islamic laws that were covered expressly in the Qur’an were referred to as hudud laws and include specifically the five crimes of theft, highway robbery, intoxication, adultery and falsely accusing another of adultery, each of which has a prescribed "hadd" punishment that cannot be forgone or mitigated. The Qur'an also details laws of inheritance, marriage, restitution for injuries and murder, as well as rules for fasting, charity, and prayer. However, the prescriptions and prohibitions may be broad, so how they are applied in practice varies. Islamic scholars, the ulema, have elaborated systems of law on the basis of these broad rules, supplemented by the hadith reports of how Muhammad and his companions interpreted them.

In current times, as Islam has spread to countries such as Iran, Indonesia, Great Britain, and the United States, not all Muslims understand the Qur'an in its original Arabic. Thus, when Muslims are divided in how to handle situations, they seek the assistance of a mufti (Islamic judge) who can advise them based on Islamic Sharia and hadith.

Islamic calendar

Islam dates from the Hijra, or migration from Mecca to Medina. Year 1, AH (Anno Hegira) corresponds to AD 622 or 622 CE, depending on the notation preferred (see Common Era). It is a lunar calendar, but differs from other such calendars (e.g. the Celtic calendar) in that it omits intercalary months, being synchronized only with lunations, but not with the solar year, resulting in years of either 354 or 355 days. Therefore, Islamic dates cannot be converted to the usual CE/AD dates simply by adding 622 years. Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years in the Gregorian calendar.

Denominations

There are a number of Islamic religious denominations, each of which have significant theological and legal differences from each other but possess similar essential beliefs. The major schools of thought are Sunni and Shi'a; Sufism is generally considered to be a mystical inflection of Islam rather than a distinct school. According to most sources, present estimates indicate that approximately 85% of the world's Muslims are Sunni and approximately 15% are Shi'a. [12] [13]

Sunni

The Sunni are the largest group in Islam. In Arabic, as-Sunnah literally means principle or path. Sunnis and Shi'a believe that Muhammad is a perfect example to follow, and that they must imitate the words and acts of Muhammad as accurately as possible. Because of this reason, the Hadith in which those words and acts are described are a main pillar of Sunni doctrine.

Sunnis recognize four major legal traditions (madhhabs): Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanafi, and Hanbali. All four accept the validity of the others and Muslims choose any one that he/she finds agreeable to his/her ideas. There are also several orthodox theological or philosophical traditions (kalam).

Shi'a

Shi'a Muslims, the second-largest branch, differ from the Sunni in rejecting the authority of the first three caliphs. They honor different accounts of Muhammad (hadith) and have their own legal traditions. Shi'a scholars have a larger authority than Sunni scholars and have greater room for interpretation. The concept of Imamah (leadership) plays a central role in Shi'a doctrine. Shi'a Muslims hold that leadership should not be passed down through a system such as the caliphate, but rather, descendants of Muhammad should be given this right as Imams.

Sufism

Sufism is a spiritual practice followed by both Sunni and Shi'a. Sufis generally feel that following Islamic law or jurisprudence (or fiqh) is only the first step on the path to perfect submission; they focus on the internal or more spiritual aspects of Islam, such as perfecting one's faith and fighting one's own ego (nafs). Most Sufi orders, or tariqas, can be classified as either Sunni or Shi'a. However, there are some that are not easily categorized as either Sunni or Shi'a, such as the Bektashi. Sufis are found throughout the Islamic world, from Senegal to Indonesia. Their innovative beliefs and actions often come under criticism from Wahhabis, who consider certain practices to be against the letter of Islamic law.

Others

Salafis are a smaller, more recent Sunni group. To other Muslims and non-Muslims Wahabi is the term most popularly associated with them. Followers of Salafism often also use the term "Ahl-us Sunnah Wa Jama'ah" as a label for their following, which would translate to English as "Congregation of the Followers of Sunnah". Salafiyyah is a movement commonly thought as founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab in the 18th century in what is present-day Saudi Arabia. They are classified as Sunni. One of the foremost principles, however, is the abolition of "schools of thoughts" (legal traditions), and the following of Muhammad directly through the study of the sciences of the Hadith (prophetic traditions). The Hanbali legal tradition is the strongest school of thought where the Islamic law in Saudi Arabia is derived from, and they have had a great deal of influence on the Islamic world because of Saudi control of Mecca and Medina, the Islamic holy places, and because of Saudi funding for mosques and schools in other countries. The majority of Saudi Islamic scholars are considered as Wahhabis by other parts of the Islamic world.

Another sect which dates back to the early days of Islam is that of the Kharijites. The only surviving branch of the Kharijites are the Ibadi Muslims. Ibadhism is distinguished from Shiism by its belief that the Imam (Leader) should be chosen solely on the basis of his faith, not on the basis of descent, and from Sunnism in its rejection of Uthman and Ali and strong emphasis on the need to depose unjust rulers. Ibadi Islam is noted for its strictness, but, unlike the Kharijites proper, Ibadis do not regard major sins as automatically making a Muslim an unbeliever. Most Ibadi Muslims live in Oman.

Another trend in modern Islam is that which is sometimes called progressive. Followers may be called Ijtihadists. They may be either Sunni or Shi'ite, and generally favor the development of personal interpretations of Qur'an and Hadith. See: Liberal Islam

One very minuscule group, based primarily in the Western United States, follows the teachings of Rashad Khalifa and calls itself the "Submitters". They reject the Hadith and Fiqh, and say that they follow the Qur'an only. They also consider Khalifa a messenger after Muhammad (Rashad Khalifa proclaimed himself the "Messenger of the Covenant"). Most Muslims of both the Sunni and the Shia branches consider this group to be heretical. Some Muslims, however, will reject Khalifa's messenger status but will also reject both the Fiqh and the Hadith.

There is also a small sect of Islam in India and Pakistan which identifies themselves as Ahmadi Muslims. Although this sect is altogether rejected by mainstream Islamic scholars, they continue to identify themselves as Muslims.

Islam and other religions

The Qur'an contains both injunctions to respect other religions, and to fight and subdue unbelievers during war. Some Muslims have respected Jews and Christians as fellow people of the book (monotheists following Abrahamic religions), while others have reviled them as having abandoned monotheism and corrupted their scriptures. At different times and places, Islamic communities have been both intolerant and tolerant. Support can be found in the Qur'an for both attitudes.

The classical Islamic solution was a limited tolerance — Jews and Christians were to be allowed to privately practice their faith and follow their own family law. They were called dhimmis and paid a special tax called the jizya, since the zakat paid by Muslims was not compulsory on them. The status of dhimmis is a matter of dispute, with some claiming that dhimmis were persecuted second-class citizens, and others that their lot was not difficult.

The medieval Islamic state was often more tolerant than many other states of the time which insisted on complete conformity to a state religion. The record of contemporary Muslim-majority states is mixed. Some are generally regarded as tolerant, while others have been accused of intolerance and human rights violations.

One of the open issues is the claim from hardline Muslims that once a certain territory has been under 'Muslim' rule, it can never be relinquished anymore, and that such a period of islamic rule would give the Muslims an eternal right on the claimed territory. This claim is particularly controversial with regard to Israel and to a lesser degree Spain and parts of the Balkan.

Related Faiths

The Yazidi, Sikhism, Bábísm, Bahá'í Faith, Berghouata and Ha-Mim religions either emerged out of an Islamic milieu or have beliefs in common with Islam in varying degrees; in almost all cases those religions were also influenced by traditional beliefs in the regions where they emerged, but consider themselves independent religions with distinct laws and institutions. The last two religions no longer have any followers.

History

Islamic history begins in Arabia in the 7th century with the emergence of Muhammad. Within a century of his death, an Islamic state stretched from the Atlantic ocean in the west to central Asia in the east, which, however, was soon torn by civil wars (fitnas). After this, there would always be rival dynasties claiming the caliphate, or leadership of the Muslim world, and many Islamic states or empires offering only token obedience to an increasingly powerless caliph.

Nonetheless, the later empires of the Abbasid caliphs and the Seljuk Turks were among the largest and most powerful in the world.[citation needed] After the disastrous defeat of the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Christian Europe launched a series of Crusades and for a time captured Jerusalem. Saladin, however, recaptured Palestine and defeated the Shiite Fatimids.

From the 14th to the 17th centuries, one of the most important Muslim territories was the Mali Empire, whose capital was Timbuktu.

In the 18th century, there were three great Muslim empires: the Ottoman in Turkey, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean; the Safavid in Iran; and the Mogul in India. By the 19th century, these realms had fallen under the sway of European political and economic power, due to European industrialism and colonialism. Following WWI, the remnants of the Ottoman empire were parceled out as European protectorates or spheres of influence. Islam and Islamic political power have revived in the 20th century. However, the relationship between the West and the Islamic world remains uneasy.[citation needed]

Contemporary Islam

Although the most prominent movement in Islam in recent times has been fundamentalist Islamism, there are a number of liberal movements within Islam, which seek alternative ways to align the Islamic faith with contemporary questions.[citation needed]

Early Sharia had a much more flexible character than is currently associated with Islamic jurisprudence, and many modern Muslim scholars believe that it should be renewed, and the classical jurists should lose their special status. This would require formulating a new fiqh suitable for the modern world, e.g. as proposed by advocates of the Islamization of knowledge, and would deal with the modern context. One vehicle proposed for such a change has been the revival of the principle of ijtihad, or independent reasoning by a qualified Islamic scholar, which has lain dormant for centuries.[citation needed]

This movement does not aim to challenge the fundamentals of Islam; rather, it seeks to clear away misinterpretations and to free the way for the renewal of the previous status of the Islamic world as a centre of modern thought and freedom.[citation needed]

Many Muslims counter the claim that only "liberalization" of the Islamic Sharia law can lead to distinguishing between tradition and true Islam by saying that meaningful "fundamentalism", by definition, will eject non-Islamic cultural inventions — for instance, acknowledging and implementing Muhammad's insistence that women have God-given rights that no human being may legally infringe upon. Proponents of modern Islamic philosophy sometimes respond to this by arguing that, as a practical matter, "fundamentalism" in popular discourse about Islam may actually refer, not to core precepts of the faith, but to various systems of cultural traditionalism.[citation needed]

The demographics of Islam today

Based on the figures published in the 2005 CIA World Factbook ([1]), Islam is the second largest religion in the world. According to the Al Islam, and Samuel Huntington, Islam is growing faster numerically than any of the other major world religions. Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance estimate that it is growing at about 2.9% annually, as opposed to 2.3% per year global population growth. Most of this growth is due to the high population growth in many Islamic countries (six out of the top-ten countries in the world with the highest birth rates are majority Muslim [14]). The birth rates in some Muslim countries are now declining [15].

Commonly cited estimates of the Muslim population today range between 900 million and 1.5 billion people (cf. Adherents.com); estimates of Islam by country based on U.S. State Department figures yield a total of 1.48 billion, while the Muslim delegation at the United Nations quoted 1.2 billion as the global Muslim population in September 2005.[citation needed]

Only 18% of Muslims live in the Arab world; 20% are found in Sub-Saharan Africa, about 30% in the South Asian region of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, and the world's largest single Muslim community (within the bounds of one nation) is in Indonesia. There are also significant Muslim populations in China, Europe, Central Asia, and Russia.

France has the highest Muslim population of any nation in Western Europe, with up to 6 million Muslims (10% of the population [16]). Albania has the highest proportion of Muslims as part of its population in Europe (70%), although this figure is only an estimate (see Islam in Albania). Countries in Europe with many Muslims include Bosnia and Herzegovina (estimated around 50 % are Bosniaks, Muslims) and Macedonia where over 30 % of the population is Muslim, mostly ethnic Albanians in Macedonia. The country in Europe with most Muslims is Russia. The number of Muslims in North America is variously estimated as anywhere from 1.8 to 7 million.[citation needed]

Political and religious extremism

The term Islamism describes a set of political ideologies derived from Islamic fundamentalism.[citation needed] Most Islamist ideologies hold that Islam is not only a religion, but also a political system that governs the legal, economic and social imperatives of the state according to interpretations of Islamic Law.

Islamic extremist terrorism refers to acts of terrorism claimed by its supporters and practitioners to be in furtherance of the goals of Islam. The validity of an Islamic justification for these acts is contested by other Muslims.[citation needed] Islamic extremist violence is not synonymous with all terrorist activities committed by Muslims. Nationalists, separatists, and others in the Muslim world often derive inspiration from secular ideologies. These are not well described as either Islamic extremist or Islamist.[citation needed]

Symbols of Islam

Muslims do not accept any icon or color as sacred to Islam as they believe that worshipping symbolic or material things is against the spirit of monotheism. Many people assume that the star and crescent symbolize Islam, but these were actually the insignia of the Ottoman Empire, [17] not of Islam as a whole. The color green is often associated with Islam as well; this is custom and not prescribed by religious scholars. However, Muslims will often use elaborately calligraphed verses from the Qur'an and pictures of the Ka'bah as decorations in mosques, homes, and public places. The Qur’anic verses are believed to be sacred.

Controversies and criticisms

Islam has been the subject of criticism and controversy from the very start, and is often viewed with considerable negativity in the West when compared to other religions. [18] Islam, the Qur'an, and Muhammad, have all been subject to both criticism and vilification. [19]

The main points of secular criticism are:

- The use of fatwas to punish violations committed by Muslims (e.g. the death edict against British writer Salman Rushdie). [20],[21]

- Human rights abuses by the Taliban and other fundamentalist governments. [22], [23]

- The use of violence by Islamist militant organizations as a means of spreading Islam. [24], [25]

- The state of women's rights in muslim societies. [26], [27]

- The suppression of free speech (e.g. Muhammad Cartoons). [28], [29]

See also

- Islamic economics

- Islamic law

- Islamic literature

- Islamic studies

- List of converts to Islam

- List of Muslims

- Muslim World

- Political Islamism

- Religion

- Timeline of Islamic history

References

- ^ Vartan Gregorian (2003). Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. pp. p. ix. ISBN 081573283X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Teece, Geoff (2005). Religion in Focus: Islam. Smart Apple Media. pp. p. 10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ John L Esposito (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press US. pp. p. 2. ISBN 0195157133.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ John L Esposito (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press US. pp. p. 1. ISBN 0195157133.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Nelson, Lynn Harry. "Islam and the Prophet Muhammad". Kansas University. Retrieved 2006-06-17. - "One must remember that we are talking about the Muslim expansion, not Arab conquests. The expansion of Islam was as much, or perhaps much more, a matter of religious conversion than it was of military conquest."

- ^ "USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts". Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ^ Nigosian, S A (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- ^ Eastman, Roger (1999). The Ways of Religion: An Introduction to the Major Traditions. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. p. 431.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Lloyd Ridgeon (2003). Major World Religions: From Their Origins to the Present. New York, NY: RoutledgeCorizon. pp. p. 258.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Arshad Khan (2003). Islam 101: Principles and Practice. Lincoln, Nebraska: Writers Club Press. pp. p.54.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Goldschmidt, Arthur (2002). A Concise History of the Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. pp. p. 48.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ John L Esposito (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press US. pp. p. 2. ISBN 0195157133.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Sunni and Shia Islam, Country Studies, retrieved April 04, 2006

- ^ Stats > People > Birth rate > Top 10, NationMaster.com, retrieved March 27, 2006

- ^ "The demographics of radical Islam", by Spengler, Asia Time Online, August 23, 2005, retrieved March 27, 2006

- ^ France, CIA - The World Factbook, January, 2006, retrieved March 27, 2006

- ^ Crescent Moon: Symbol of Islam?, by Huda, About, retrieved April 01, 2006

- ^ Ernst, Carl (2002). Rethinking Muhammad in the Contemporary World) p. 11

- ^ Ernst, Carl (2002). Rethinking Muhammad in the Contemporary World) p. 11

- ^ Wikipedia: Fatwas

- ^ Wikipedia: List of well-known fatwas

- ^ Wikipedia: Taliban Movement

- ^ Universal Human Rights and Human Rights in Islam by David Littman

- ^ Coming to Terms: Fundamentalists or Islamists? by Martin Kramer

- ^ Wikipedia: Islamic fundamentalism

- ^ Muslim Women's League

- ^ Wikipedia: Sharia - Domestic Punishment

- ^ Wikipedia: International reactions to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

- ^ The proof of the necessity of killing anyone who curses the Prophet or finds fault with him masud.co.uk

Bibliography

- Khan, Muhammad Muhsin & Al-Hilali, Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din. Noble Quran, ISBN 1591440041

- Mubarkpuri, Saifur-Rahman. The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Dar-us-Salam, ISBN 9960899-55-1

- Al-Asqalani, Ibn Hajar. Bulugh Al-Maram, ISBN 1591440564

- Arberry, A. J. The Koran Interpreted: a translation by A. J. Arberry. Touchstone, ISBN 0684825074

- Kramer, Martin. The Islamism Debate. University Press, (1997) ISBN 9652240249

- Rahman, Fazlur. Islam. University of Chicago Press; 2nd edition, (1979) ISBN 0226702812

- Safi, Omid. Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender and Pluralism. Oneworld Publications, (2003) ISBN 185168-316-X

- Tibi, Bassam. The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder. Univ. of California Press, (1998) ISBN 0520088689

- Najeebabadi, Akbar Shah. History of Islam. Dar-us-Salam, ISBN 1591440319

- Walker, Benjamin. Foundations of Islam: The Making of a World Faith, Peter Owen Publishers, London and New York, 1978, ISBN 0720610389; Harper Collins, New Dehli, 1999.

External links

Academic resources

- University of South California Compedium of Muslim Texts

- Encyclopedia of Islam (Overview of World Religions)

- Islam and Western Ideologies

- Authentic Audio Collection on Various Topics in Urdu Language

- Unit on Islam from the NITLE Arab Culture and Civilization Online Resource

- Resources on Quran, History and Polemics

- Golden age of Arab and Islamic Culture

- Adoption of Islam by Turks

Directories

- Islam in Western Europe, the United Kingdom, Germany and South Asia

- Dmoz.org Open Directory Project: Islam (a list of links of Islam)

- Islam World

Islam and the arts, sciences, and philosophy

- Daily Ahadith List - Sahih Hadith in your email Daily

- Islamic Art (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

- Muslim Heritage (Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, UK)

- Islamic Architecture (IAORG) illustrated descriptions and reviews of a large number of mosques, palaces, and monuments.

- Islamic Philosophy (Journal of Islamic Philosophy, University of Michigan)

- Famous Muslim scientists & scholars

- Islam and Science

- muslimphotos.net Photos from Muslim locations from all over the world

- Muslim Civilisation