Lviv pogroms (1941): Difference between revisions

m Repair duplicate template arguments |

|||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

'''Notes''' |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

{{Reflist|2}} |

||

'''Sources''' |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Beorn |first1=Waitman Wade |author-link = Waitman Wade Beorn|title=The Holocaust in Eastern Europe: At the Epicenter of the Final Solution |date=2018 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=1474232221 |ref = harv}} |

*{{cite book |last1=Beorn |first1=Waitman Wade |author-link = Waitman Wade Beorn|title=The Holocaust in Eastern Europe: At the Epicenter of the Final Solution |date=2018 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=1474232221 |ref = harv}} |

||

*{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nd9WzIkTJrAC&pg=PA14&dq=8789+prisoners |title=Harvest of Despair |first=Karel Cornelis |last=Berkhoff |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]]|isbn=0674020782 |year=2004|ref=harv}} |

*{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nd9WzIkTJrAC&pg=PA14&dq=8789+prisoners |title=Harvest of Despair |first=Karel Cornelis |last=Berkhoff |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]]|isbn=0674020782 |year=2004|ref=harv}} |

||

Revision as of 18:59, 9 December 2019

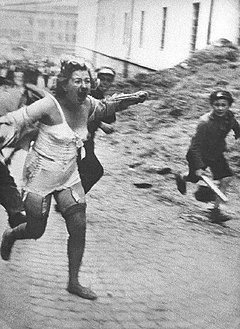

Woman chased by men and youth armed with clubs, Medova Street in Lviv, 1941 | |

| Date | June 1941 - July 1941 |

|---|---|

| Location | Lviv, Occupied Poland |

| Coordinates | 49°30′36″N 24°00′36″E / 49.510°N 24.010°E |

| Type | Beatings, sexual abuse, robberies, mass murder |

| Participants | Germans, Ukrainian nationalists, local crowds |

| Deaths | Thousands of Jews (see estimates) |

The Lviv pogroms were the consecutive massacres (pogroms) of Jews in June and July 1941 in the city of Lwów in Eastern Poland/Western Ukraine (now Lviv, Ukraine). The massacres were perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists, German death squads, and local crowds from 30 June to 2 July, and from 25 to 29 July, during the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Thousands of Jews were killed both in the pogroms and in the Einsatzgruppen killings.

Background

Lviv (Lwów) was a multicultural city just prior to World War II, with a population of slightly over 300,000. Ethnic Poles constituted about 50 per cent of the population, with Jews at 30 per cent (100,000) and Ukrainians at 16 per cent.[1] After the joint Soviet-German invasion, on 28 September 1939, the USSR and Germany signed the German–Soviet Frontier Treaty assigning about 200,000 km² of land inhabited by 13.5 million people of all nationalities to the Soviet Union. Lviv was then annexed to the Soviet Union.[2]

According to Soviet Secret Police (NKVD) records, nearly 9,000 prisoners were murdered in the Ukrainian SSR in the NKVD prisoner massacres, immediately after the start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, 22 June 1941.[3] Due to the confusion that reigned during the Soviet's rapid retreat and incomplete records, the NKVD number is most likely an undercounting. According to estimates by contemporary historians, the number of victims in Western Ukraine was probably between 10,000 on the low end and 40,000 on the high end.[4] By ethnicity, Ukrainians comprised roughly 70 per cent of victims, with Poles at 20 per cent.[5]

First pogrom and Einsatzgruppen killings

At the time of the German attack, about 160,000 Jews lived in the city.[6] Immediately after the German army entered Lwów in the early morning hours of 30 June, Ukrainian nationalists proclaimed an independent Ukrainian state. Another factor that played a role in the subsequent violence was the discovery of thousands of corpses in three city prisons in the aftermath of the NKVD prisoner massacres; the victims, including Ukrainian nationalists, had been killed by the Soviets prior to the German occupation, once NKVD realised they would be unable to evacuate the prisoners.[7] A Wehrmacht report stated that the majority of the Soviet murder victims were Ukrainian. Although a significant number of Jewish prisoners had also been among the victims of the NKVD massacres (including intellectuals and political activists), the Jews were targeted collectively.[citation needed]

Already on 30 June, Jews were being press ganged by the Germans to remove bodies of the victims from the prisons, as well as perform other tasks, such as clearing bomb damage and cleaning buildings. Some Jews were abused by the Germans and even murdered. On the afternoon of the same day, the German military was reporting that the Lviv population was taking out its anger about the prison murders "on the Jews (...) who had always collaborated with the Bolsheviks", according to the account.[8] A full-blown pogrom began on the next day, 1 July. Jews were taken from their apartments, made to clean streets on their hands and knees, or perform rituals that identified them with Communism. Gentile residents assembled in the streets to watch.[9] Jewish women were singled out for humiliation: they were beaten, abused, and forcibly disrobed. On one such occasion, a German military propaganda company filmed the scene. Rapes were also reported.[10] Jews continued to be brought to the three prisons, first to exhume the bodies, and then to be killed.[11]

An ad hoc Ukrainian People's Militia was assembled to spearhead the first pogrom.[12] Sonderkommando 4a, part of Einsatzgruppe C, arrived on 2 July, at which point violence escalated further. More Jews were brought to the prisons where they were shot and buried in freshly dug pits.[13] It was also at this point that the Ukrainian militia was subordinated to the SS.[14] In addition to participation in the pogrom, Einsatzgruppe C conducted a series of mass murder operations which continued for the next few days. Unlike the "prison actions", these shootings were marked by the absence of crowd participation. With the assistance from Ukrainian militia, Jews were herded into a stadium, from where they were taken on trucks to the shooting site.[15]

The Ukrainian militia received assistance from the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists,[16] unorganized ethnic nationalists, as well as from ordinary crowd and even underage youth. At least two members of the OUN-B, Ivan Kovalyshyn and Mykhaylo Pecharsʹkyy, have been identified by the historian John Paul Himka from several photographs of the pogrom.[17]

Petlura days

A second pogrom took place in the last days of July 1941 and was labeled "Petlura Days" (Aktion Petliura) after the assassinated Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura.[18] The killings were organized with German encouragement, but the pogrom also had ominous undertones of religious bigotry with Andrey Sheptytsky's awareness,[19] and with Ukrainian militants from outside the city joining the fray with farm tools.[citation needed] Sheptytsky became disillusioned with Nazi Germany only in mid-1942 after his National Council was banned, with thousands of Ukrainians sent to slave labour.[19][20] In the morning of 25 July 1941 the Ukrainian auxiliary police began arresting Jews in their homes, while the civilians participated in acts of violence against them in the streets. Captured Jews were dragged to the Jewish cemetery and to the Łąckiego Street prison, where they were fatally shot out of the public eye. Ukrainian police circulated in groups of five and consulted prepared lists from OUN. Some 2,000 people were murdered in approximately three days. Thousands of other Jews were injured.[citation needed]

Number of victims

The estimates for the total number of victims vary. A subsequent account by the Lviv Judenrat estimated that 2,000 Jews disappeared or were killed in the first days of July. A German security report of 16 July stated that 7,000 Jews were "captured and shot". The former is possibly an undercounting, while the German numbers are likely exaggerated, to impress higher command.[21]

According to the Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, the first pogrom resulted in 2,000 to 5,000 Jewish victims. Additional 2,500 to 3,000 Jews were shot in the Einsatzgruppen killings that immediately followed. During the so-called "Petlura Days" massacre of late July, more than 1,000 Jews were killed.[18] According to the historian Peter Longerich, the first pogrom cost at least 4,000 lives. It was followed by the additional 2,500 to 3,000 arrests and executions in subsequent Einsatzgruppen killings, with "Petlura Days" resulting in more than 2,000 victims.[22]

The historian Dieter Pohl (historian) estimates that 4,000 of Lviv Jews were killed in the pogroms between 1 and 25 July.[23] According to the historian Richard Breitman, 5,000 Jews died as a result of the pogroms. In addition, some 3,000 mostly Jews were executed in the municipal stadium by the Germans.[24]

Aftermath

The German propaganda passed off all victims of the NKVD killings in Lviv as Ukrainians even though the lists of prisoners left behind by the Soviets had about one-third of distinctly Polish and Jewish names in them. Over the next two years both German and pro-Nazi Ukrainian press including Ukrains'ki shchodenni visti, Krakivs'ki visti and others, went on to describe horrific acts of chekist torture (real or imagined) with the number of Ukrainian casualties multiplied out of thin air, wrote historian John-Paul Himka.[25] The German propaganda made newsreels that purported to implicate Soviet Jews in the killing of Ukrainians, and the German propaganda broadcast them across occupied Europe.[25]

The Lwów Ghetto was established in November 1941 on the orders of Fritz Katzmann, the Higher SS and Police Leader (SSPF) of Lemberg and one of the most prolific mass murderers in the SS.[26] At its peak, the ghetto held some 120,000 Jews, most of whom were deported to the Belzec extermination camp or killed locally during the next two years. Following the 1941 pogroms and Einsatzgruppe killings, harsh conditions in the ghetto, and deportations to Belzec and the Janowska concentration camp, located on the outskirts of the city, resulted in the almost complete annihilation of the Jewish population locally. By the Soviet forces reached Lviv on 21 July 1944, less than 1 per cent of Lviv's Jews had survived the occupation.[18]

In historical memory

Historians have since established that the David Lee Preston collection of photographs once believed to show the victims of NKVD killings, is, in fact, showing the victims of a subsequent pogrom.[27]

In 2008, the Security Service of Ukraine released documents that it stated indicated that the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists may have been involved to a lesser degree than originally thought. The collection of documents, titled "For the Beginning: Book of Facts" (Do pochatku knyha faktiv), has been recognized by historians including John-Paul Himka, Per Anders Rudling, and Marco Carynnyk, as an attempt at manipulating World War II history.[28][29][30]

See also

- History of the Jews in Poland

- History of the Jews in Ukraine

- Jedwabne pogrom

- Kaunas pogrom

- Żydokomuna

References

Notes

- ^ Himka 2011, p. 210.

- ^ Gross, Jan Tomasz (2002). Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 17, 28–30. ISBN 0691096031.

- ^ Berkhoff 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Kiebuzinski & Motyl 2017, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Kiebuzinski & Motyl 2017, p. 41.

- ^ Beorn 2018, p. 136.

- ^ Himka 2011, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Himka 2011, p. 211.

- ^ Himka 2011, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Himka 2011, p. 213.

- ^ Himka 2011, p. 218.

- ^ Himka 2011.

- ^ Beorn 2018, p. 137.

- ^ Himka 2011, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Himka 2011, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Breitman, Richard (2010). Hitler's Shadow: Nazi War Criminals, U.S. Intelligence, and the Cold War. DIANE Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-1437944297.

In Lwów, a leaflet warned Jews that, "You welcomed Stalin with flowers. We will lay your heads at Hitler's feet." At a 6 July 1941 meeting in Lwów, Stepan Bandera loyalists determined: "We must finish them off..." Back in Berlin, Yaroslav Stetsko reported it all to him.[12]

- ^ Himka 2015.

- ^ a b c Kulke 2012, p. 802.

- ^ a b Mordecai Paldiel (2000). Saving the Jews: Men and Women who Defied the Final Solution. Taylor Trade Publications. pp. 362–364. ISBN 1589797345. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ David Cymet (2012). History vs. Apologetics: The Holocaust, the Third Reich, and the Catholic Church. Lexington Books. p. 232. ISBN 978-0739132951. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Himka 2011, p. 221.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 194.

- ^ Lower 2012, p. 204.

- ^ Richard Breitman. "Himmler and the 'Terrible Secret' among the Executioners". Journal of Contemporary History; Vol. 26, No. 3/4: The Impact of Western Nationalisms (Sep. 1991), pp. 431-451

- ^ a b Himka 2014.

- ^ Claudia Koonz (2 November 2005). "SS Man Katzmann's "Solution of the Jewish Question in the District of Galicia"" (PDF). The Raul Hilberg Lecture. University of Vermont: 2, 11, 16–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Bogdan Musial, Bilder einer Ausstellung: Kritische Anmerkungen zur Wanderausstellung "Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941 bis 1944." Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 47. Jahrg., 4. H. (October 1999): 563–581. "David Lee Preston collection."

- ^ "Falsifying World War II history in Ukraine". Kyiv Post. 8 May 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Per A. Rudling, The OUN, the UPA and the Holocaust: A Study in the Manufacturing of Historical Myths, The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies, No. 2107, November 2011, ISSN 0889-275X, p. 29

- ^ "Історична напівправда гірша за одверту брехню". LB.ua. 5 November 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

Sources

- Beorn, Waitman Wade (2018). The Holocaust in Eastern Europe: At the Epicenter of the Final Solution. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 1474232221.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berkhoff, Karel Cornelis (2004). Harvest of Despair. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674020782.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Himka, John-Paul (2011). "The Lviv Pogrom of 1941: The Germans, Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Carnival Crowd". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 53 (2–4): 209–243. doi:10.1080/00085006.2011.11092673. ISSN 0008-5006. Taylor & Francis.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Himka, John-Paul (2014). "Ethnicity and the Reporting of Mass Murder: "Krakivs'ki visti", the NKVD Murders of 1941, and the Vinnytsia Exhumation". Chapter: Ethnicizing the Perpetrators. University of Alberta. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Himka, John Paul (2015). "Ще кілька слів про львівський погром. ФОТО: Михайло Печарський". Lviv pogrom of 1941. Історична правда. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kiebuzinski, Ksenya; Motyl, Alexander (2017). "Introduction". The Great West UkrainianPrison Massacre of 1941: A Sourcebook. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-8964-834-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Kulke, Christine (2012). "Lwów". In Geoffrey P. Megargee (ed.). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Vol. II, part A. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lower, Wendy (2012). "The Wehrmacht in the War of Ideologies: The Army and Hitler's Criminal Orders on the Eastern Front". Axis collaboration, Operation Barbarossa, and the Holocaust in Ukraine. University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-407-9.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)

External links

- Contemporaneous German footage of the pogrom, via United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (graphic imagery).