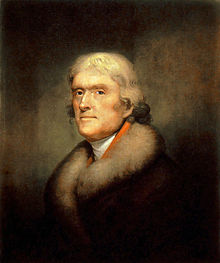

Thomas Jefferson

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

Thomas Jefferson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Third President | |

| Vice President | Aaron Burr; George Clinton |

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| Personal details | |

| Nationality | american |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743–July 4, 1826) was one of the most influential Founders of the United States and one of the earliest and most prominent American politicians and statesmen.

Jefferson was the son of a successful Virginia planter and surveyor who was educated at the College of William and Mary before becoming a lawyer. He practiced law before entering politics in the House of Burgesses and wrote extensively on political philosophy as well as the British Empire's policies towards the American colonies.

A believer in a meritocratic democracy (Jeffersonian democracy), deism, and liberalism, equality, and liberty, Jefferson became a leader of the American Revolution. At the same time he was a landowner, author, surveyor, inventor, architect, etymologist, and slaveowner who maintained intense interests in dozens of fields and contributed to agriculture, horticulture, archaeology, mathematics, and paleontology. He designed his estate, Monticello, founded the University of Virginia, and wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

As a member of the Continental Congress, Jefferson authored most of the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776. During the Articles of Confederation period after the end of the American Revolutionary War, Jefferson served as governor of Virginia (1779-1781), and minister to France (1785–1789).

After the U.S. Constitution was adopted in 1789, Jefferson founded and led the Democratic-Republican Party and served as the first Secretary of State under George Washington (1790–1793). Jefferson lost to the Federalist John Adams in the 1796 election and served as Vice President during Adams's term. In the 1800 election, Jefferson defeated Adams and became the first President of the United States from the Democratic-Republican Party, which dominated American politics for the next 25 years. Jefferson's term was marked by his belief in agrarianism, individual liberty, and limited government, sparking the development of a distinct American identity defined by republicanism. During this term, Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase and commissioned the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Jefferson was re-elected in the 1804 election. His second term was dominated by foreign policy concerns, as American neutrality was imperiled by war between Britain and France.

After leaving the presidency, Jefferson continued to be active in public affairs until his death in 1826. Many people consider Jefferson to be among the most brilliant men ever to occupy the presidency, and in the United States he is often revered by leftists. John F. Kennedy famously welcomed 49 Nobel Prize winners to the White House in 1962 with the statement that "I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone." His portrait appears on the $2 bill and the nickel.

Early life

Jefferson was born on April 2, 1743, according to the Julian calendar used at the time ("old style") but under the Gregorian calendar ("new style") adopted during his lifetime he was born on April 13.

Jefferson's was born into a prosperous Virginia family. His father was Peter Jefferson, a planter and surveyor who owned a plantation in Albemarle County called Shadwell and his mother was Jane Randolph. Both parents were from families that had been settled in Virginia for several generations.

Education

In 1752, Jefferson began attending a local school run by William Douglas, a Scottish reverend. In 1757, when Jefferson was 14 years old, his father died.

After his father's death he was taught at the school of the learned James Maury, a reverend, from 1758 to 1760. The school was in Fredericksville parish, twelve miles from Shadwell, and Jefferon boarded with with Maury's family. There he received a classical education and studied history, and natural science. At the age of nine, Jefferson began studying the classical languages of Latin and Greek as well as French.

Jefferson entered the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg at the age of 16 and spent two years there, from 1760 to 1762. There he studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under William Small, who introduced the enthusiastic Jefferson in the writings of British Empiricists, including John Locke, Bacon, and Sir Issac Newton. There he reportedly studied 15 hours a day, perfected French, carried his Greek grammar book wherever he went, practiced the violin, and favored Tacitus and Homer.

In college, Jefferson was a member of the secret Flat Hat Club, now the namesake of the college's daily student newspaper. After graduating in 1762 with highest honors, Jefferson studied law with his friend and mentor George Wythe and was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1767.

Law practice

In 1779 at Jefferson's behest, William and Mary appointed George Wythe the first Professor of Law in America. In 1783, Jefferson was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws by William and Mary. As Governor of Virginia, Jefferson continued to advocate educational reforms at William & Mary including the nation's first elective system of course study.

Jefferson inherited about 5,000 acres (20 km²) of land and dozens of slaves from his father, out of which he created his home which would eventually be known as Monticello. He practiced law in Virginia and in 1772 Jefferson married a widow, Martha Wayles Skelton. Jefferson served in the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1774, he wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America which was intended as instructions for the Virginia delegates to a national congress. The summary was considered to be towards the radical side at the time in terms of the view of the colonies towards the British government. It was not followed by the Virginia delegates, but it was published nationally and won Jefferson some national admirers who agreed with his ideas and who were impressed by his writing ability.

Jefferson was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, and a source of many other contributions to American political and civil culture. The Continental Congress delegated the task of writing the Declaration to a committee which included Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. The committee met and unanimously solicited Jefferson to prepare the draft of the Declaration alone.

The Library of Congress was founded from the sale of his collection (the Library was founded in 1800; Jefferson sold his third library to Congress in 1815). Jefferson himself designed his famous home, Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia; it included automatic doors, the first swivel chair, and other convenient devices invented by Jefferson. Nearby is the only university ever to have been founded by a President, the University of Virginia, of which the original curriculum and architecture Jefferson designed. Today, Monticello and the University of Virginia are together one of only four man-made World Heritage Sites in the United States of America.

Jefferson's interests included archeology, a discipline then in its infancy. He has sometimes been called the "father of archeology" in recognition of his role in developing excavation techniques. When exploring an Indian burial mound on his Virginia estate in 1784, Jefferson avoided the common practice of simply digging downwards until something turned up. Instead, he cut a wedge out of the mound so that he could walk into it, look at the layers of occupation, and draw conclusions from them.

Jefferson was also an avid wine lover and noted gourmet. During his ambassadorship to France (1784-1789) he took extensive trips through French and other European wine regions and sent the best back home. He is noted for the bold pronouncement: "We could in the United States make as great a variety of wines as are made in Europe, not exactly of the same kinds, but doubtless as good." While there were extensive vineyards planted at Monticello, a significant portion were of the European wine grape Vitis vinifera and did not survive the many vine diseases native to the Americas.

Jefferson's idea for the United States was that of an agricultural nation of yeoman farmers, in contrast to the vision of Alexander Hamilton, who envisioned a nation of commerce and manufacturing. Jefferson was a great believer in the uniqueness and the potential of the United States and is often classified as the forefather of American exceptionalism (see also exceptionalism).

Jefferson was the first Secretary of State of the United States, serving from 1789 until 1794. He was also the second Vice President of the United States, under John Adams from 1797 until 1801, achieving that position after getting second place in the presidential election of 1796.

An electoral tie resulted between Jefferson and Aaron Burr in the U.S. presidential election, 1800. It was resolved on February 17, 1801 when Jefferson was elected President and Burr Vice President by the United States House of Representatives. Jefferson is so far the only Vice President elected to the Presidency to serve two full terms. He was also the first Presidential candidate to be the target of a smear campaign from his opponents due to his religious beliefs. Jefferson, a Deist, was accused of being an atheist by the supporters of John Adams.

Jefferson's portrait appears on the U.S. $2 bill and the U.S. five cent piece, or nickel. Jefferson also appears on the $100 Series EE Savings Bond.

Jefferson passed away on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, on the same day as John Adams. Jefferson and Adams were the only signers of the Declaration of Independence to become presidents. He is buried on his Monticello estate. His epitaph, written by him with an insistence that only his words and "not a word more" be inscribed, reads:

- Here was buried

- Thomas Jefferson

- Author of the Declaration of American Independence

- of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom

- & Father of the University of Virginia

Jefferson was the first president to be buried in a grave as opposed to a crypt as both Washington and Adams were.

Presidency

Jefferson's presidency, from 1801 to 1809, was the first to start and end in the White House; it was also the first Democratic-Republican presidency. Jefferson was also the only Vice President to be both elected as president and serve two full terms as president of the United States.

Jefferson was a strict constructionist who compromised on his original principles during his presidency. He strayed from the principles of keeping a small navy, agrarian economy, strict constructionalism, and a small/weak government. A group called the tertium quids criticised Jefferson for his abandonment of his early principles.

Inauguration

Thomas Jefferson, powerful advocate of equality and liberty, gave his inaugural address on March 4, 1801 in Washington, DC. The principles of this address can mainly be categorized as unity and strength. At the time of Jefferson’s inauguration, the country was very much divided, mainly politically among politicians, between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. The second president, John Adams, was the only Federalist president that the USA saw. Jefferson was the first Democratic-Republican president. At this point in time it became very important to unify the country under common goals and ideas.

In the United States Declaration of Independence and the Constitution the idea that the majority couldn’t have all the power, to protect the rights of the minority, was very prominent. Jefferson largely restated these ideas in his inaugural address.

Another one of his important points was that America needs to become strong in the eyes of foreign powers. He realized the tremendous implications of being looked down upon by the mighty eyes of mother, from England, as well as other countries. Not having good relations would limit much trade and stifle the economy’s growth, as well as make America a very weak political power.

The final point Jefferson brought up is that America’s citizens are not American from birth, but from sharing the same ideas. He said this would make America a great power. He also said that Americans were enlightened by a benign religion.

Events during his presidency

- Louisiana Purchase (1803)

- Creation of the Orleans Territory in 1804

- Marbury v. Madison (1803)

- Land Act of 1804

- Twelfth Amendment is ratified (1804)

- Lewis and Clark expedition (1804-1806)

- Creation of the Louisiana Territory (later renamed the Missouri Territory) in 1805

- Tertium quids create a divide in the Republican Party (the Democratic-Republican Party)

- Embargo Act of 1807, an attempt to force respect for U.S. neutrality by ending trade with the belligerents in the Napoleonic War

- Abolition of the external slave trade in 1808

Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Thomas Jefferson | 1801–1809 |

| Vice President | Aaron Burr | 1801–1805 |

| George Clinton | 1805–1809 | |

| Secretary of State | James Madison | 1801–1809 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Samuel Dexter | 1801 |

| Albert Gallatin | 1801–1809 | |

| Secretary of War | Henry Dearborn | 1801–1809 |

| Attorney General | Levi Lincoln, Sr. | 1801–1804 |

| Robert Smith | 1805 | |

| John Breckinridge | 1805–1806 | |

| Caesar A. Rodney | 1807–1809 | |

| Postmaster General | Joseph Habersham | 1801 |

| Gideon Granger | 1801–1809 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Benjamin Stoddert | 1801 |

| Robert Smith | 1801–1810 | |

Supreme Court appointments

Jefferson appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

States admitted to the Union

Father of a university

- See article: University of Virginia

After retiring from politics, Jefferson became increasingly obsessed with founding a new institution of higher learning, specifically one free of church influences. After much planning, his dream was realized in 1819 with the founding of the University of Virginia, and upon its opening in 1825 it was then the first university to offer a full slate of elective courses to its students. One of the largest construction projects to that time in North America, it was notable for being centered about a library, rather than a church. In fact, no campus chapel was included in his original plans. Until his death, he invited students and faculty of the school to his home, Edgar Allan Poe among them.

Appearance, temperament and interests

Jefferson was six feet, two-and-one-half inches (189 cm) in height, large-boned, slender, erect and sinewy. He had angular features, very poor posture, a very ruddy complexion, strawberry blonde hair and hazel-flecked, grey eyes. In later years he was negligent in dress and loose in bearing.

There was grace, nevertheless, in his manners; and his frank and earnest address, his quick sympathy (though he seemed cold to strangers), and his vivacious, desultory, informing talk gave him an engaging charm. Beneath a quiet surface he was fairly aglow with intense convictions and a very emotional temperament. Yet he seems to have acted habitually, in great and little things, on system. The range of his interests is remarkable. For many years he was president of the American Philosophical Society.

Though it is a biographical tradition that he lacked wit, Molière and Don Quixote seem to have been his favorites; and though the utilitarian wholly crowds romanticism out of his writings, he had enough of that quality in youth to prepare to learn Gaelic in order to translate Ossian, and sent to James Macpherson for the originals.

As president he discontinued the practice of delivering the State of the Union Address in person, instead sending the address to Congress in writing (the practice was eventually revived by Woodrow Wilson); he ended up giving only two public speeches during his presidency. His reluctance to speak in public is usually attributed to his taciturnity, though some historians believe it was due to a lisp. In addition, he burned all of his letters between himself and his wife at her death, creating the portrait of a man who at times could be very private.

Political philosophy

Jefferson believed that each individual has "certain inalienable rights." That is, these rights exist with or without government; man cannot create or take them away. It is the right of "liberty" on which Jefferson is most notable for expounding. He defines it by saying "rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will within limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others. I do not add ‘within the limits of the law’, because law is often but the tyrant’s will, and always so when it violates the rights of the individual." (TJ to Isaac H. Tiffany, 1819) Hence, for Jefferson, though government cannot create a right to liberty, it can indeed violate it. And, the limit of an individual's rightful liberty is not what law says it is, but is simply a matter of stopping short of prohibiting other individuals from having the same liberty. A proper government, for Jefferson, is one that not only prohibits individuals in society from infringing on the liberty of other individuals, but also restrains itself from diminishing individual liberty.

Jefferson believed that individuals have an innate sense of morality that prescribes right from wrong when dealing with other individuals --that whether they choose to restrain themselves or not, they have an innate sense of the natural rights of others. He even believed that moral sense to be reliable enough that an anarchist society could function well, provided that it was reasonably small. On several occasions he expressed admiration for the governmentless society of the native American Indians:

- "[The Indians] had separated into so many little societies. This practice results from the circumstance of their having never submitted themselves to any laws, any coercive power, any shadow of government. Their only controls are their manners, and that moral sense of right and wrong, which, like the sense of tasting and feeling in every man, makes a part of his nature. An offence against these is punished by contempt, by exclusion from society, or, where the case is serious, as that of murder, by the individuals whom it concerns. Imperfect as this species of coercion may seem, crimes are very rare among them; insomuch that were it made a question, whether no law, as among the savage Americans, or too much law, as among the civilised Europeans, submits man to the greatest evil, one who has seen both conditions of existence would pronounce it to be the last; and that the sheep are happier of themselves, than under care of the wolves. It will be said, the great societies cannot exist without government. The savages, therefore, break them into small ones." (Notes on Virginia)

He said in a letter to Colonel Carrington: "I am convinced that those societies (as the Indians) which live without government, enjoy in their general mass an infinitely greater degree of happiness than those who live under the European governments." However, Jefferson believe anarchism to be "inconsistent with any great degree of population." (TJ to James Madison, 30 Jan 1787). Hence, he did advocate government for the American expanse provided that it exists by "consent of the governed."

In the Preamble to the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson wrote:

- We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. –That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Jefferson's dedication to "consent of the governed" was so thorough that he believed that individuals could not be morally bound by the actions of preceeding generations. This included debts as well as law. He said that "no society can make a perpetual constitution or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation." He even calculated what he believed to be the proper cycle of legal revolution: "Every constitution then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years. If it is to be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right." He arrived at 19 years through calculations with expectancy of life tables with taking into account what he believed to be the age of "maturity" when an individual is able to reason for himself (TJ to James Madison, 6 September 1789).

Jefferson believed in the principals of the Jeffersonian era, which was created and named by and after him. He believed that a federal government should have limited power, that people should work for the better of the common man, and that Americans should rely more on agriculture than industry. Also, he believed that democracy should be expanded and that the National Debt should be eliminated. However, he did not believe that living individuals had a moral obligation to repay the debts of previous generations. He said that repaying such debts was "a question of generosity and not of right" (Letter to James Madison, 6 Sep 1789).

Thomas Jefferson is considered by many historians to be the most federalist of all presidents. At first this seems to be a ludicrous assertion. How could the founder of a party known to many as the Anti-Federalist actually be one of the most federalist presidents? While Jefferson did help to found the Republican Democratic party, many of the decisions he made in office favoured a strong central government and strong executive power, trademarks of the Federalist party. Events such as the Lousiana Purchase in 1803, the Embargo Act in 1807, and the war with the Barbary pirates (1801-1805) all exemplify his uses of authority. However, despite these actions, Jefferson also cut back the Federal government's size and reduced its expenditure, both Republican actions by nature. Jefferson, although he did make some Republican changes to the Federal government, is widely considered to be the more federalist of his Republican Peers.

Religious views

On matters of religion, Jefferson was sometimes accused by his political opponents of being an atheist; however, he is generally regarded as a believer in Deism, a philosophy shared by many other notable intellectuals of his time. Jefferson repeatedly stated his belief in a creator, and in the United States Declaration of Independence uses the terms "Creator", "Nature's God", and "Divine Providence". Jefferson believed, furthermore, it was this Creator that endowed humanity with a number of inalienable rights, such as "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness". His experience in France just before the Revolution made him deeply suspicious of (Catholic) priests and bishops as a force for reaction and ignorance.

Jefferson was raised Episcopalian at a time when the Episcopal Church was the state religion in Virginia. Before the American Revolution, when the Episcopal Church was the American branch of the Anglican Church of England, Jefferson was a vestryman in his local church, a lay position that was part of political office at the time. He later removed his name from those available to become godparents, because his beliefs opposed Trinitarian theology. Jefferson later expressed general agreement with his friend Joseph Priestley's Unitarianism and wrote that he would have liked to have been a member of a Unitarian church, but there were no Unitarian churches in Virginia.

Jefferson did not believe in the divinity of Jesus, but he had high esteem for Jesus' moral teachings, which he viewed as the "principles of a pure deism, and juster notions of the attributes of God, to reform [prior Jewish] moral doctrines to the standard of reason, justice & philanthropy, and to inculcate the belief of a future state." (Letter to Joseph Priestley, April 9, 1803.)

Like most deists, Jefferson did not believe in miracles. He labored on an edited version of the Gospels, removing references to the miracles of Jesus and material he considered preternatural, leaving only Jesus' moral philosophy, of which he approved. This compilation was published after his death and became known as the Jefferson Bible.

From 1784 to 1786 Jefferson and James Madison worked together to oppose Patrick Henry's attempts to again assess taxes in Virginia to support churches. Instead, in 1786 the Virginia General Assembly passed Jefferson's Bill for Religious Freedom, which he had first submitted in 1779, and was one of only three accomplishments he put in his own epitaph. Virginia thereby became the first state to disestablish religion — Rhode Island, Delaware, and Pennsylvania never having had established religion.

Jefferson also supported what he called a "wall of separation between Church and State", which he believed was a principle expressed within the First Amendment (see Letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, 1802, and Letter to Virginia Baptists, 1808).

- "Because religious belief, or non-belief, is such an important part of every person's life, freedom of religion affects every individual. State churches that use government power to support themselves and force their views on persons of other faiths undermine all our civil rights. Moreover, state support of the church tends to make the clergy unresponsive to the people and leads to corruption within religion. Erecting the 'wall of separation between church and state,' therefore, is absolutely essential in a free society.

- "We have solved ... the great and interesting question whether freedom of religion is compatible with order in government and obedience to the laws. And we have experienced the quiet as well as the comfort which results from leaving every one to profess freely and openly those principles of religion which are the inductions of his own reason and the serious convictions of his own inquiries."

- — as quoted in the Letter to the Virginia Baptists (1808). This is his second use of the term "wall of separation," here quoting his own use in the Danbury Baptist letter. This wording was cited several times by the Supreme Court as an accurate description of the Establishment Clause: Reynolds (98 U.S. at 164, 1879); Everson (330 U.S. at 59, 1947); McCollum (333 U.S. at 232, 1948).

He further developed his thoughts in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1779), quoted from Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: Writings (1984), p. 347:

- "[N]o man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities."

During his presidency, Jefferson refused to issue proclamations calling for days of prayer and thanksgiving. Moreover, his private letters indicate he was skeptical of too much interference by clergy in matters of civil government. His letters contain the following observations: "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government" (Letter to Alexander von Humboldt, December 6, 1813), and, "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own" (Letter to Horatio G. Spafford, March 17, 1814). "May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all), the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government" (Letter to Roger C. Weightman June 24, 1826).

Jefferson's desire to erect a "wall of separation" did not include a desire to inhibit the personal religious lives of public officials. Jefferson himself attended certain public Christian services during his presidency. He also had friends who were clergy, and he supported some churches financially. Moreover, he personally believed, as did Deist and humanist John Locke, that human rights were endowed by a God: "Can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are a gift of God? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that His justice cannot sleep forever" (Notes on the State of Virginia, 1781-1785 Query 18). Though not religious himself, he viewed religious opinions in others, including public officials, as a purely personal matter with which the state should not interfere:

- "Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," thus building a wall of separation between church and State" (Letter to Danbury Baptist Association, CT, January 1, 1802).

For the full text of this letter and that to which Jefferson was replying see Wikisource.

Influences

Jefferson was influenced heavily by the ideas of many European Enlightenment thinkers. His political principles were heavily influenced by John Locke (particularly relating to the principles of inalienable rights and popular sovereignty) and Thomas Paine's Common Sense.

Jefferson and slavery

Jefferson's personal records show he owned 187 slaves, some of whom were inherited at the death of his wife. Some find it hypocritical that he both owned slaves and yet was publicly outspoken in his belief that slavery was immoral. Many of his slaves were considered property that was held as a lien for his many accumulated debts.

His ambivalence can be seen for example, in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence, which Jefferson wrote, in which he condemned the British crown for sponsoring the importation of slavery to the colonies, charging that the crown "has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere..." This language was dropped from the Declaration at the request of delegates from South Carolina and Georgia. In 1769, as a member of the state legislature, Jefferson proposed for that body to emancipate slaves in Virginia, but he was unsuccessful. In 1778, the legislature passed a bill he proposed to ban further importation of slaves into Virginia; although this did not bring complete emancipation, in his words, it "stopped the increase of the evil by importation, leaving to future efforts its final eradication."

The Sally Hemings controversy

A subject of considerable controversy since Jefferson's own time was whether Jefferson was the father of any of the children of his slave Sally Hemings. A full account of the controversy can be found in the Sally Hemings article.

Two major, mutually contradictory studies were released in the early 2000s. A study by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation states that "it is very unlikely that Randolph Jefferson or any Jefferson other than Thomas Jefferson was the father of her children," while a study by an independent Scholars Commmission concludes that the Jefferson paternity thesis is not persuasive.

David N. Mayer, a member of the Scholars Commission, says in his own writings that there is "the possibility that Jefferson's brother Randolph or one of Randolph Jefferson's five sons could have fathered one or more of Sally Hemings' children." He also states that, "Indeed, eight of these 25 Jefferson males lived within 20 miles (a half-day's ride) of Monticello—including Thomas Jefferson's younger brother, Randolph Jefferson, and Randolph's five sons, who ranged in age from about 17 to 26 at the time of Eston's birth." All of these men could have passed down the Y chromosome used as "proof". Professor Mayer's independent report also suggests that the Foundation report is flawed by biases and faulty assumptions (including the assumption that only one man fathered all of Sally Hemings' children).

Significantly, everyone who has researched the issue -- regardless which side they take on the Jefferson-Hemings paternity question -- agree that there is no evidence supporting the original allegation, published by Thomas Callender in 1802, that Jefferson fathered Sally Hemings' first child in France prior to 1790. All the documentary evidence shows that Hemings' first child, Harriet, was born in 1795 -- years after the mythical child "Tom" that Callender alleged.

Architecture

Jefferson was an accomplished architect who was extremely influential in bringing the Neo-Classical style he encountered in France to the United States. He felt that it reflected the ideas of republic and democracy where the prevalent British styles represented the monarchy. His major works included Monticello (his home), the Virginia State Capitol and the University of Virginia. Jefferson's buildings helped initiate the ensuing American fashion for Federal style architecture.

Honors

Jefferson was ranked #64 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

Further reading

Writings

- Thomas Jefferson: Writings : Autobiography / Notes on the State of Virginia / Public and Private Papers / Addresses / Letters (1984, ISBN 094045016X) The Library of America edition; see discoussion of sources at [1]. There are numerous one-volume editions; this is perhaps the best place to start.

- Bergh , Albert Ellery Ed. The Writings Of Thomas Jefferson 19 vol. (1907), not as complete nor as accurate as Boyd edition, but covers TJ from 1801 to his death. It is out of copyright, and so is online, at [2]

- Boyd, Julian P. et al, eds. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. The definitive multivolume edition; available at major academic libraries. 31 volumes covers TJ to 1800, with 1801 due out in 2006. See description at [3]

- The Jefferson Cyclopedia (1900) large collection of TJ quotes arranged by 9000 topics; searchable; copyright has expired and it is online at [4]

- The Thomas Jefferson Papers, 1606-1827, 27,000 original manuscript documents at the Library of Congress. Online at [5]

- Adams, Dickinson W., ed. Jefferson's Extracts from the Gospels (1983). All three of Jefferson's versions of the Gospels, with relevant correspondence about his religious opinions. Valuable introduction by Eugene Sheridan.

- Bear, Jr., James A., ed. Jefferson's Memorandum Books, 2 vols. (1997). Jefferson's account books with records of daily expenses.

- Betts, Edwin Morris and James A. Bear, Jr., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (1986). Correspondence of Jefferson with his children and grandchildren.

- Cappon, Lester J., ed. The Adams-Jefferson Letters (1959).

- Chinard, Gilbert, ed. The Commonplace Book of Thomas Jefferson: A Repertory of His Ideas on Government (1926). Jefferson's legal commonplace book.

- Howell, Wilbur Samuel, ed. Jefferson's Parliamentary Writings (1988). Jefferson's Manual of Parliamentary Practice, written when he was vice-president, with other relevant papers.

- Shuffelton, Frank, ed. Notes on the State of Virginia (1999).

- Online, Notes on the State of Virginia [6]

- Smith, James Morton, ed. The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776-1826, 3 vols. (1995).

- Wilson, Douglas L., ed. Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book (1989).

Secondary Scholarly Books

- Bernstein, R. B. Thomas Jefferson. (2003) Excellent compact biography.

- Bernstein, R. B. Thomas Jefferson: The Revolution of Ideas (2004). for a middle school audience.

- Channing, Edward. The Jeffersonian System(1906) older but solid coverage of politics 1801-1811.

- Cunningham, Noble E. In Pursuit of Reason (1988) good short biography

- Ellis, Joseph J. American Sphinx (1996). Prize winning essays.

- Ellis, Joseph J. "American Sphinx: The Contradictions of Thomas Jefferson." essay by leading scholar online at [7]

- Gordon-Reed, Annette. Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy (1999).

- Hitchens, Christopher. Thomas Jefferson: Author of America (2005). Short essay.

- Lewis, Jan Ellen, and Onuf, Peter S., eds. Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, Civic Culture. (1999).

- McDonald, Forrest. The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson (1987) intellectual history approach to TJ's presidency

- Malone, Dumas. Jefferson and His Time, 6 vols. (1948-82). The standard scholarly multi-volume biography of TJ by Dumas Malone.

- Mayer, David N. The Constitutional Thought of Thomas Jefferson (2000).

- Miller, John Chester. The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery. (1977)

- Onuf, Peter S. Jefferson's Empire: The Languages of American Nationhood. (2000).

- Onuf, Peter S., ed. Jeffersonian Legacies. (1993).

- Peterson, Merrill D. The Jefferson Image in the American Mind (1960), how Americans interpreted and remembered TJ.

- Peterson, Merrill D. Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1992). Standard scholarly biography.

- Sloan, Herbert J. Principle and Interest: Thomas Jefferson and the Problem of Debt (1995). Shows the burden of debt in TJ' personal finances and poltical thought.

- Smelser, Marshall. The Democratic Republic: 1801-1815 (1968) good overview by a scholar who greatly admired TJ

- Tucker, Robert W. and David C. Hendrickson. Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson (1992) best guide to foreign policy

Online sources

- [8] Jefferson: Man of the Millenium

- [9] Quotations from Jefferson

- [10] Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, ed., 19 vol. (1905). 5145KB zipped ASCII file

- [11] Selected Letters.

See also

- Clay S. Jenkinson

- Philip Mazzei

- [The Rotunda (University of Virginia)]]

- List of places named for Thomas Jefferson

External links

- Works by Thomas Jefferson at Project Gutenberg

- Biography on White House website

- University of Virginia biography

- Frank E. Grizzard, Jr.'s Thomas Jefferson Webpages

- The Papers of Thomas Jefferson at the Avalon Project (includes Inaugural Addresses, State of the Union Addresses, and other material)

- Library of Congress: Jefferson timeline

- "The Hobby of My Old Age": Jefferson's University of Virginia

- B. L. Rayner's 1829 Life of Thomas Jefferson, an on-line etext

- A bio of his father Peter Jefferson

- "Thomas Jefferson, the 'Negro President'". Chronicle of Founding Father's Three-Fifths Slave Vote Victory. NPR. February 16, 2004.

- Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and the Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen Article by Iain Mclean.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- 1743 births

- 1826 deaths

- 18th century philosophers

- Ambassadors of the United States

- American archaeologists

- American architects

- American inventors

- Continental Congressmen

- Deist thinkers

- English Americans

- Enlightenment philosophers

- Governors of Virginia

- People from Virginia

- Presidents of the United States

- Signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence

- Thomas Jefferson

- U.S. Founding Fathers

- U.S. Secretaries of State

- Unitarian Universalists

- University of Virginia

- Vice Presidents of the U.S.

- Welsh-Americans

- Polymaths