Subantarctic

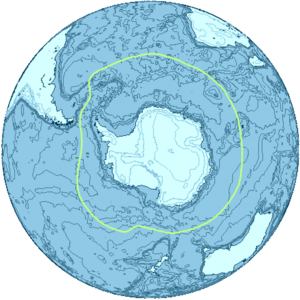

The Subantarctic is a region in the southern hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46° - 60° south of the equator. The subantarctic region includes many islands in the southern parts of the Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean and Pacific Ocean, especially those situated north of the Antarctic Convergence. Subantarctic glaciers are, by definition, located on islands within the subantarctic region. All glaciers located on the continent of Antarctica are by definition considered to be antarctic glaciers.

History

Geography

The subantarctic region is comprised of two geographic zones and three distinct fronts. The northernmost boundary of the subantarctic region is the rather ill-defined Subtropical Front (STF), also referred to as the Subtropical Convergence. To the south of the STF is a geographic zone, the Subantarctic Zone (SAZ). South of the SAZ is the Subantarctic Front (SAF). South of the SAF is another marine zone, called the Polar Frontal Zone (PFZ). The SAZ and the PFZ together form the subantarctic region. The southernmost boundary of the PFZ (and hence, the southern border of the subantarctic region) is the Antarctic Convergence, located approximately 200 kilometers south of the Antarctic Polar Front (APF).[1]

Influence of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and thermohaline circulation

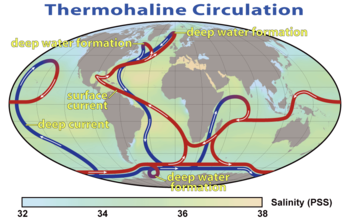

The Subantarctic Front, found between 48°S and 58°S in the Indian and Pacific Ocean and between 42°S and 48°S in the Atlantic Ocean, defines the northern boundary of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (or ACC).[1] The ACC is the most important ocean current in the Southern Ocean, and the only current that flows completely around the Earth. Flowing eastward through the southern portions of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, the ACC links these three otherwise separate oceanic basins. Extending from the sea surface to depths of 2000-4000 meters, and with a width of as great as 2000 kilometers, the ACC transports more water than any other ocean current.[2] The ACC carries up to 150 Sverdrups (150 million cubic meters per second), equivalent to 150 times the volume of water flowing in all the world's rivers.[3] The ACC and the global thermohaline circulation strongly influence regional and global climate as well as underwater biodiversity.[4]

Another factor that contributes to the climate of the subantarctic region, though to a much lesser extent than the thermohaline circulation, is the formation of Antarctic Bottom Water (ABW) by halothermal dynamics. The halothermal circulation is that portion of the global ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and evaporation.

Definition of subantarctic: political versus scientific

Several distinct water masses converge in the immediate vicinity of the APF or Antarctic Convergence (in particular the Subantarctic Surface Water (Subantarctic Mode Water or SAMW), Antarctic Surface Water, and the Antarctic Intermediate Water). This convergence creates a unique environment, noted for its very high marine productivity, especially for Antarctic krill. Because of this, all lands and waters situated south of this point are considered to belong to the Antarctic from a climatological, biological and hydrological standpoint.[5] However, the text of the Antarctic Treaty, article VI ("Area covered by Treaty") states: "The provisions of the present Treaty shall apply to the area south of 60º South latitude".[6] Therefore, Antarctica is defined from a political standpoint as all land and ice shelves south of 60°S latitude.

Subantarctic islands

Tristan da Cunha group, Île Amsterdam, Île Saint-Paul, and Gough Island are all isolated volcanic islands situated at between 37° - 40° south of the equator, just south of the southern Horse latitudes. Because they are located far to the north of the Antarctic Convergence and have a relatively temperate climate, they are not typically considered to be subantarctic islands.

At between 46° - 50° south of the equator, in the region often referred to as the Roaring Forties, are the Crozet Islands, Prince Edward Islands, Bounty Islands, Snares Islands, Kerguelen Islands, Antipodes Islands, and Auckland Islands. These islands, all located approximately on the Antarctic Convergence (roughly the northern boundary of the subantarctic region), are properly considered to be subantarctic islands.

At between 51° - 56° south of the equator, the Falkland Islands, Isla de los Estados, Ildefonso Islands, Diego Ramírez Islands, and other islands associated with Tierra del Fuego and Cape Horn, lie north of the Antarctic Convergence in the region often referred to as the Furious Fifties. Unlike other subantarctic islands, these islands have trees, temperate grasslands (mostly tussac grass), and even arable land. They also lack tundra and permanent snow and ice at their lowest elevations. Despite their more southerly location, it is debatable whether these islands should be considered as such because their climate and geography differs significantly from other subantarctic islands.

At between 52° - 57° south of the equator, Campbell Island group, Heard Island and McDonald Islands, Bouvet Island, South Georgia Group, Macquarie Island, and South Sandwich Islands are also located in the Furious Fifties. The geography of these islands is characterized by tundra, permafrost, and volcanoes. These islands are situated south of the Antarctic Convergence, but north of the 60° latitude (the continental limit according to the Antarctic Treaty).[6] Therefore despite their being located south of the Antarctic Convergence, they should still be considered to be subantarctic islands by virtue of their location north of the 60° latitude.

At between 60° - 69° south of the equator, the South Orkney Islands, South Shetland Islands, Balleny Islands, Scott Island, and Peter I Island are all properly considered to be antarctic islands for the following three reasons:

- they are all located south of the Antarctic Convergence

- they are all located within the Southern (or Antarctic) Ocean

- they are all located south of the 60° latitude (in the region often referred to as the Shrieking Sixties)

In light of the above considerations, the following should be considered to be subantarctic islands:

Subantarctic glaciers

This is a list of glaciers in the subantarctic. This list includes one snow field (Murray Snowfield). Snow fields are not glaciers in the strict sense of the word, but they are commonly found at the accumulation zone or head of a glacier.[9] For the purposes of this list, Antarctica is defined as any latitude further south than 60º (the continental limit according to the Antarctic Treaty).[6]

Climate

Impact of climate change on SAMW

Together, the Subantarctic Mode Water (SAMW) and Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) act as a carbon sink, absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide and storing it in solution. If the SAMW temperature increases as a result of climate change, the SAMW will have less capacity to store dissolved carbon dioxide. Research using a computerized climate system model suggests that if atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration were to increase to 860 ppm by the year 2100 (roughly double today's concentration), the SAMW will decrease in density and salinity. The resulting reductions in the subduction and transport capacity of SAMW and AAIW water masses could potentially decrease the absorption and storage of CO2 in the Southern Ocean.[10]

Retreat of subantarctic glaciers

Glaciers appear to be retreating at significant rates throughout the southern hemisphere. With respect to glaciers of the Andes mountains in South America, abundant evidence has been collected from ongoing research at Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia,[11] Quelccaya Ice Cap and Qori Kalis Glacier in Peru,[12][13] Zongo, Chacaltaya and Charquini glaciers in Bolivia,[14] the Aconcagua River Basin in the central Chilean Andes, [15] and the Northern Patagonian and Southern Patagonian ice fields.[16][17][18] Retreat of glaciers in New Zealand[19] and Antarctica is also well documented.

Bearing this in mind, it should come as no surprise that many subantarctic glaciers are also in retreat. Mass balance is significantly negative on many glaciers on Kergeulen Island, Heard Island, South Georgia and Bouvet Island. In 1947, Heard Island's glaciers covered 288 km2 or 79 percent of the island. By 1988 this had decreased by 11 percent to 257 km2. By 2000, the Stephenson, Brown and Baudissin glaciers had retreated even further.[20]

The island's steep topography means that glaciers are relatively thin - about 55m deep on average. The largest glacier, Gotley, originating on the island's highest point, Mawson Peak (2745 m) is 27 km2 in area and 13.2 km long. Smaller glaciers such as Nares, Mary Powell, Brown, Deacock and those on the Laurens Peninsula have significantly receded, but the larger glaciers such as Gotley, Abbotsmith, Downes and Ealey show little or no change since 1947.[20]

Heard Island is cold and steep with a high snowfall. Many larger glaciers are unable to lose much ice in the narrow coastal melt zone. If this zone were wider some of these glaciers would be several kilometers longer, but instead the sea's action removes ice from glacier tongues. For such glaciers, up to 80 percent of their volume loss is through calving. Loss through melting is unlikely to be considerable even if conditions were significantly warmer.[20]

The smaller, shorter glaciers are much more sensitive to temperature effects. Laurens Peninsula glaciers, whose maximum elevation is only 500m above sea level, are particularly vulnerable. With a warming of 1°C the accumulation zone above the end-of-summer snowline elevation of about 300m would recede to about 450m elevation due to rain and increased melt. With an accumulation zone reduced to a range of only 50m elevation, the glacier retreats until the elevation range of the melt zone is similar in size. This illustrates much of what has been happening for Laurens Peninsula glaciers since 1947, during which time their total area has decreased by over 30 percent. Jacka Glacier in the early 1950s had receded only slightly from its position in the late 1920s, but by 1997 it had receded about 700m back from the coastline.[20][21][22][23][24]

See also

References

- ^ a b Ryan Smith, Melicie Desflots, Sean White, Arthur J. Mariano, Edward H. Ryan (2008). "Surface Currents in the Southern Ocean:The Antarctic CP Current". The Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS). Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Klinck, J. M., W. D. Nowland Jr. (2001). "Antarctic Circumpolar Current". Encyclopedia of Ocean Science (1st ed.). New York: Academic Press. pp. 151–159.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Joanna Gyory, Arthur J. Mariano, Edward H. Ryan. "The Gulf Stream". The Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS). Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Ray Lilley (19 May 2008). "Millions of tiny starfish inhabit undersea volcano". Associated Press. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ reference needed

- ^ a b c Office of Polar Programs (OPP) (26 April 2010). "The Antarctic Treaty". The National Science Foundation, Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d "Antarctic Names". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Antarctic Gazetteer". Australian Antarctic Data Centre. Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Dr. Sue Ferguson, United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. "Types of Glacier". University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado: National Snow and Ice Data Center. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Stephanie M. Downes, Nathaniel L. Bindoff, Stephen R. Rintoul (2009). "Impacts of Climate Change on the Subduction of Mode and Intermediate Water Masses in the Southern Ocean". Journal of Climate. 22 (12): 3289–3302. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2653.1. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|day=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cristian Huggel (2007). "Review and reassessment of hazards owing to volcano–glacier interactions in Colombia" (PDF). Annals of Glaciology. 45: 128–136. doi:10.3189/172756407782282408. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Richard S. Williams, Jr., and Jane G. Ferrigno (09 February 1999). "Peruvian Cordilleras". United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ L.G. Thompson, E. Mosley-Thompson; et al. (01 June 2010). "Peru - Quelccaya (1974 - 1983)". Byrd Polar Research Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Bernard Francou (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement) (17 January 2001). "Small Glaciers Of The Andes May Vanish In 10-15 Years". UniSci, International Science News. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Francisca Bown, Andres Rivera, Cesar Acuna (2008). "Recent glacier variations at the Aconcagua Basin, central Chilean Andes" (PDF). Annals of glaciology. 48 (2): 43–48. doi:10.3189/172756408784700572. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jonathan Amos (27 April 2004). "Patagonian ice in rapid retreat". BBC News. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Mariano H. Masiokas, Andrés Rivera, Lydia E. Espizua, Ricardo Villalba, Silvia Delgado and Juan Carlos Aravena (2009). "Glacier fluctuations in extratropical South America during the past 1000 years". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 281 (3–4): 242–268. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.08.006. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Huge glaciers retreat on a large scale in Patagonia, South America". Earth Observation research Center. July 15, 2005. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Glaciers of New Zealand". Satellite Image Atlas of Glaciers of the World. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d Andrew Ruddell (25/05/2010). "Our subantarctic glaciers: why are they retreating?". Glaciology Program, Antarctic CRC and AAD. Retrieved 01 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Allison, I.F. and Keage, P.L. (1986). "Recent changes in the glaciers of Heard Island". Polar Record. 23 (144): 255–271.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|day=and|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Major, J.J. and Newhall, C.G. (1989). "Snow and ice perturbation during historical volcanic eruptions and the formation of lahars and floods". Bulletin of Volcanology. 52: 1–27.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|day=and|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Quilty, P.G. and Wheller, G. (2000). "Heard Island and the McDonald Islands: A window into the Kerguelen Plateau (Heard Island Papers)". Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 133 (2): 1–12.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|day=and|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Budd, G.M. (2000). Changes in Heard Island glaciers, king penguins and fur seals since 1947 (Heard Island Papers). Vol. 133. pp. 47–60.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|journal=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|day=and|month=(help)