Sargon of Akkad

| Sargon | ||

|---|---|---|

| King of Akkad | ||

| ||

| Bust of an Akkadian ruler, probably Sargon, Nineveh, ca. 23rd – 22nd century BC. | ||

| Reign | ca. 2270 BC – 2215 BC | |

| Full name | Birth name unknown; regnal name was Šarru-kin ("the true King" or "the legitimate King") | |

| Titles | King of Kish, Lagash, Umma, Uruk, overlord of Sumer, Elam, Mari, and Yarmuti. | |

| Born | ca. 2300 BC | |

| Azupiranu, Mesopotamia (?) | ||

| Died | ca. 2215 BC (aged 85) | |

| Akkad, Mesopotamia (?) | ||

| Successor | Rimush | |

| Wife/wives | Tashlultum | |

| Issue | Enheduanna, Rimush, Manishtushu, Ibarum and Abaish-Takal. | |

| Royal House | House of Sargon | |

| Dynasty | Akkadian dynasty | |

| Father | La'ibum (natural); Akki (foster-) | |

| brother | unknown | |

Template:Fix bunching Template:Fix bunching

Sargon of Akkad, also known as Sargon the Great "The Great King" (Akkadian Šarru-kinu, meaning "the true king" or "the king is legitimate"), was an Akkadian emperor famous for his conquest of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th and 23rd centuries BC.[1] The founder of the Dynasty of Akkad, Sargon reigned from 2334 to 2279 BC (short chronology).[2] He became a prominent member of the royal court of Kish, ultimately overthrowing its king before embarking on the conquest of Mesopotamia.

Sargon's vast empire is known to have extended from Elam to the Mediterranean Sea, including Mesopotamia, parts of modern-day Iran and Syria, and possibly parts of Anatolia and the Arabian peninsula. He ruled from a new capital, Akkad (Agade), which the Sumerian king list claims he built (or possibly renovated), on the left bank of the Euphrates.[3] He is the first person in recorded history to create a multiethnic, centrally ruled empire, and his dynasty controlled Mesopotamia for around a century and a half.[4]

Origins and rise to power

The story of Sargon's birth and childhood is given in the "Sargon legend", a Sumerian text purporting to be Sargon's biography. The extant versions are incomplete, but the surviving fragments name Sargon's father as La'ibum. After a lacuna, the text skips to Ur-Zababa, king of Kish, who awakens after a dream, the contents of which are not revealed on the surviving portion of the tablet. For unknown reasons, Ur-Zababa appoints Sargon as his cupbearer. Soon after this, Ur-Zababa Marth invites Sargon to his chambers to discuss a dream of Sargon's, involving the favor of the goddess Inanna and the drowning of Ur-Zababa by the goddess. Deeply frightened, Ur-Zababa orders Sargon murdered by the hands of Beliš-tikal, the chief smith, but Inanna prevents it, demanding that Sargon stop at the gates because of his being "polluted with blood." When Sargon returns to Ur-Zababa, the king becomes frightened again, and decides to send Sargon to king Lugal-zage-si of Uruk with a message on a clay tablet asking him to slay Sargon.[5] The legend breaks off at this point; presumably, the missing sections described how Sargon becomes king.[6]

The Sumerian king list relates: "In Agade [Akkad], Sargon, whose father was a gardener,[7] the cupbearer of Ur-Zababa, became king, the king of Agade, who built Agade; he ruled for 56 years."[8] The claim that Sargon was the original founder of Akkad has come into question in recent years, with the discovery of an inscription mentioning the place and dated to the first year of Enshakushanna, who almost certainly preceded him.[9] This claim of the king list had been the basis for earlier speculation by a number of scholars that Sargon was an inspiration for the biblical figure of Nimrod.[10] The Weidner Chronicle states that it was Sargon who built Babylon "in front of Akkad."[11][12] The Chronicle of Early Kings likewise states that late in his reign, Sargon "dug up the soil of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Agade."[12][13] More recently, some researchers have stated that those sources may refer to Sargon II of the Neo-Assyrian Empire rather than Sargon of Akkad. [14]

A Neo-Assyrian text from the 7th century BC purporting to be Sargon's autobiography asserts that the great king was the illegitimate son of a priestess. In the Neo-Assyrian account Sargon's birth and his early childhood are described thus:

My mother was a high priestess, my father I knew not. The brothers of my father loved the hills. My city is Azupiranu, which is situated on the banks of the Euphrates. My high priestess mother conceived me, in secret she bore me. She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen she sealed my lid. She cast me into the river which rose over me. The river bore me up and carried me to Akki, the drawer of water. Akki, the drawer of water, took me as his son and reared me. Akki, the drawer of water, appointed me as his gardener. While I was a gardener, Ishtar granted me her love, and for four and ... years I exercised kingship.[15]

The image of Sargon as a castaway set adrift on a river resembles the better-known birth narrative of Moses. Scholars such as Joseph Campbell and Otto Rank have compared the 7th century BC Sargon account with the obscure births of other heroic figures from history and mythology, including Karna, Oedipus, Paris, Telephus, Semiramis, Perseus, Romulus, Gilgamesh, Cyrus, Jesus, and others.[16]

Formation of the Akkadian Empire

After coming to power in Kish, Sargon soon attacked Uruk, which was ruled by Lugal-Zage-Si of Umma.[17] He captured Uruk and dismantled its famous walls. The defenders seem to have fled the city, joining an army led by fifty ensis from the provinces. This Sumerian force fought two pitched battles against the Akkadians, as a result of which the remaining forces of Lugal-Zage-Si were routed.[18] Lugal-Zage-Si himself was captured and brought to Nippur; Sargon inscribed on the pedestal of a statue (preserved in a later tablet) that he brought Lugal-Zage-Si "in a dog collar to the gate of Enlil."[19] Sargon pursued his enemies to Ur before moving eastwards to Lagash, to the Persian Gulf, and thence to Umma. He made a symbolic gesture of washing his weapons in the "lower sea" (Persian Gulf) to show that he had conquered Sumer in its entirety.[20]

Another victory Sargon celebrated was over Kashtubila, king of Kazalla. According to one ancient source, Sargon laid the city of Kazalla to waste so effectively "that the birds could not find a place to perch away from the ground."[21]

To help limit the chance of revolt in Sumer he appointed a court of 5,400 men to "share his table" (i.e., to administer his empire).[22] These 5,400 men may have constituted Sargon's army.[23] The governors chosen by Sargon to administer the main city-states of Sumer were Akkadians, not Sumerians.[24] The Semitic Akkadian language became the lingua franca, the official language of inscriptions in all Mesopotamia, and of great influence far beyond. Sargon's empire maintained trade and diplomatic contacts with kingdoms around the Arabian Sea and elsewhere in the Near East. Sargon's inscriptions report that ships from Magan, Meluhha, and Dilmun, among other places, rode at anchor in his capital of Agade.[25]

The former religious institutions of Sumer, already well-known and emulated by the Semites, were respected. Sumerian remained, in large part, the language of religion and Sargon and his successors were patrons of the Sumerian cults. Enheduanna, the author of several Akkadian hymns who is identified as Sargon's daughter, was made priestess of Nanna, the moon-god of Ur. Sargon styled himself "anointed priest of Anu" and "great ensi of Enlil".[26]

Wars in the northwest and east

Shortly after securing Sumer, Sargon embarked on a series of campaigns to subjugate the entire Fertile Crescent. According to the Chronicle of Early Kings, a later Babylonian historiographical text:

[Sargon] had neither rival nor equal. His splendor, over the lands it diffused. He crossed the sea in the east. In the eleventh year he conquered the western land to its farthest point. He brought it under one authority. He set up his statues there and ferried the west's booty across on barges. He stationed his court officials at intervals of five double hours and ruled in unity the tribes of the lands. He marched to Kazallu and turned Kazallu into a ruin heap, so that there was not even a perch for a bird left.[12]

Sargon captured Mari, Yarmuti, and Ebla as far as the Cedar Forest (Amanus) and the silver mountain (Taurus). The Akkadian Empire secured trade routes and supplies of wood and precious metals could be safely and freely floated down the Euphrates to Akkad.[27]

In the east, Sargon defeated an invasion by the four leaders of Elam, led by the king of Awan. Their cities were sacked; the governors, viceroys and kings of Susa, Barhashe, and neighboring districts became vassals of Akkad, and the Akkadian language made the official language of international discourse.[28] During Sargon's reign, Akkadian was standardized and adapted for use with the cuneiform script previously used in the Sumerian language. A style of calligraphy developed in which text on clay tablets and cylinder seals was arranged amidst scenes of mythology and ritual.[29]

Later reign

The text known as Epic of the King of the Battle depicts Sargon advancing deep into the heart of Anatolia to protect Akkadian and other Mesopotamian merchants from the exactions of the King of Burushanda (Purshahanda).[30] The same text mentions that Sargon crossed the Sea of the West (Mediterranean Sea) and ended up in Kuppara.[31]

Famine and war threatened Sargon's empire during the latter years of his reign. The Chronicle of Early Kings reports that revolts broke out throughout the area under the last years of his overlordship:

Afterward in his [Sargon's] old age all the lands revolted against him, and they besieged him in Akkad; and Sargon went onward to battle and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed. Afterward he attacked the land of Subartu in his might, and they submitted to his arms, and Sargon settled that revolt, and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed, and he brought their possessions into Akkad. The soil from the trenches of Babylon he removed, and the boundaries of Akkad he made like those of Babylon. But because of the evil which he had committed, the great lord Marduk was angry, and he destroyed his people by famine. From the rising of the sun unto the setting of the sun they opposed him and gave him no rest.[32]

Later literature proposes that the rebellions and other troubles of Sargon's later reign were the result of sacrilegious acts committed by the king. Modern consensus is that the veracity of these claims are impossible to determine, as disasters were virtually always attributed to sacrilege inspiring divine wrath in ancient Mesopotamian literature.[33]

Legacy

Sargon died, according to the short chronology, around 2215 BC. His empire immediately revolted upon hearing of the king's death. Most of the revolts were put down by his son and successor Rimush, who reigned for nine years and was followed by another of Sargon's sons, Manishtushu (who reigned for 15 years).[34] Sargon was regarded as a model by Mesopotamian kings for some two millennia after his death. The Assyrian and Babylonian kings who based their empires in Mesopotamia saw themselves as the heirs of Sargon's empire. Kings such as Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC) showed great interest in the history of the Sargonid dynasty, and even conducted excavations of Sargon's palaces and those of his successors.[35] Indeed, such later rulers may have been inspired by the king's conquests to embark on their own campaigns throughout the Middle East. The Neo-Assyrian Sargon text challenges his successors thus:

The black-headed peoples [Sumerians] I ruled, I governed; mighty mountains with axes of bronze I destroyed. I ascended the upper mountains; I burst through the lower mountains. The country of the sea I besieged three times; Dilmun I captured. Unto the great Dur-ilu I went up, I ... I altered ... Whatsoever king shall be exalted after me, ... Let him rule, let him govern the black-headed peoples; mighty mountains with axes of bronze let him destroy; let him ascend the upper mountains, let him break through the lower mountains; the country of the sea let him besiege three times; Dilmun let him capture; To great Dur-ilu let him go up.[36]

Another source attributed to Sargon the challenge "now, any king who wants to call himself my equal, wherever I went [conquered], let him go."[37]

Stories of Sargon's power and that of his empire may have influenced the body of folklore that was later incorporated into the Bible. A number of scholars have speculated that Sargon may have been the inspiration for the biblical figure of Nimrod, who figures in the Book of Genesis as well as in midrashic and Talmudic literature.[10] The Bible mentions Akkad as being one of the first city-states of Nimrod's kingdom, but does not explicitly state that he built it.[38]

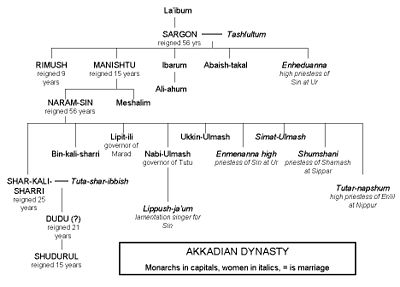

Family

The name of Sargon's main wife Tashlultum and those of a number of his children are known to us. His daughter Enheduanna, who flourished during the late 24th and early 23rd centuries BC, was a priestess who composed ritual hymns.[39] Many of her works, including her Exaltation of Inanna, were in use for centuries thereafter.[40] Sargon was succeeded by his son, Rimush; after Rimush's death another son, Manishtushu, became king. Two other sons, Shu-Enlil (Ibarum) and Ilaba'is-takal (Abaish-Takal), are known.[41]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Sargon" was likely a regnal name; his given name is unknown. For a detailed discussion of Sargon's name, see Lewis 1984:277–292.

- ^ This according to the Sumerian king list, the actual dates of Sargon's reign are impossible to determine with certainty; see, e.g., Kramer, The Sumerians passim.

- ^ Kramer, The Sumerians 1963:60–61. Akkad was probably located between Sippar and Kish.

- ^ Van der Mieroop 64–72.

- ^ "The Sargon Legend." The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Oxford University, 2006. cf. the Greek myth of Bellerophon. A similar account appears in the Norse legend of Amleth, which Shakespeare adapted in Hamlet.

- ^ Cooper 67–82.

- ^ Thorkild Jacobsen, in his edition of the Sumerian King List, marked this clause as a lacunae, indicating his uncertainty about its meaning. (The Sumerian King List, Assyriological Studies, No. 11 (Chicago: Oriental Institute, 1939), p. 111)

- ^ Confusingly, Ur-Zababa and Lugal-zage-si are both listed as kings, but several generations apart.

- ^ Van de Mieroop, Cuneiform Texts 75.

- ^ a b Levin 350–356; Poplicha 303–317.

- ^ Grayson 19:51.

- ^ a b c Chronicle of Early Kings at Livius.org. Translation adapted from A.K. Grayson, Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles (1975) and Jean-Jacques Glassner, Mesopotamian Chronicles (Atlanta, 2004).

- ^ Grayson 20:18–19

- ^ Stephanie Dalley, Babylon as a Name for Other Cities Including Nineveh, in [1] Proceedings of the 51st Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Oriental Institute SAOC 62, pp. 25–33, 2005

- ^ King 1907: 87–96

- ^ Rank passim; MacKenzie 126. While Moses is supposed to have lived centuries after Sargon, the exact chronological relationship between the two narratives is uncertain. In any event, the account of Exodus turns the theme on its head—rather than a royal fostered by commoners before rediscovering his royal blood, Moses is the son of slaves who is fostered by the daughter of Pharaoh. See, e.g. Lewis 211–272.

- ^ While Sargon is often credited with the first true empire, Lugal-Zage-Si preceded him; after coming to power in Umma he had conquered or otherwise come into possession of Ur, Uruk, Nippur, and Lagash. Lugal-Zage-Si claimed rulership over lands as far away as the Mediterranean. See Beaulieu 43.

- ^ Kramer, The Sumerians 61.; Van de Mieroop, History 64–66.

- ^ Oppenheim 267.

- ^ Oppenheim 267.

- ^ Oppenheim 266.

- ^ Kramer, The Sumerians 61.

- ^ Frayne 31.

- ^ Van der Mieroop, History 62–68.

- ^ Kramer, The Sumerians 62, 289–291.

- ^ See, e.g., Van der Mieroop, History 67–68.

- ^ Kramer, The Sumerians passim.

- ^ It remained so for several centuries; the Amarna letters of the 14th century BC were largely written in Akkadian.

- ^ Britannica.

- ^ The oldest extant text was found on an Akkadian-language tablet in the Amarna archives; translations have since been discovered in Hittite and Hurrian. Postgate 216.

- ^ Possibly the Akkadian word for Keftiu, an ancient locale usually associated with Crete or Cyprus. See Wainright 197–212; Strange 395–396; Vandersleyen 209.

- ^ Botsforth 27–28. However Oppenheim translates the last sentence as "From the East to the West he [i.e. Marduk] alienated (them) from him and inflicted upon (him as punishment) that he could not rest (in his grave)." Ancient Near Eastern Texts, p. 266

- ^ Britannica

- ^ Kramer, The Sumerians 61–63; Roux 155.

- ^ Oates 162.

- ^ Barton 310, as modernized by J. S. Arkenberg.

- ^ Nougayrol 169.

- ^ Genesis 10:10. In the Sumerian king list, Sargon is credited with the construction of the city, but see above for controversy surrounding this assertion.

- ^ Schomp 81.

- ^ Schomp 81; Kramer, History Begins at Sumer 351; Hallo passim.

- ^ Frayne 3637.

References

- Albright, W. F., A Babylonian Geographical Treatise on Sargon of Akkad's Empire, Journal of the American Oriental Society (1925).

- Alotte De La Fuye, M. Documents présargoniques, Paris, 1908–20.

- Biggs, R.D. Inscriptions from Tell Abu Salabikh, Chicago, 1974.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain, et al. A Companion to the Ancient near East. Blackwell, 2005.

- Botsforth, George W., ed. "The Reign of Sargon". A Source-Book of Ancient History. New York: Macmillan, 1912.

- Cooper, Jerrold S. and Wolfgang Heimpel. "The Sumerian Sargon Legend." Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 103, No. 1, (Jan.-Mar. 1983).

- Deimel, A. Die Inschriften von Fara, Leipzig, 1922–24.

- Diakonov, Igor, 'On the area and population of the Sumerian city-State', VDI (1950), 2, pp. 77–93.

- Frankfort, H. 'Town planning in ancient Mesopotamia', Town Planning Review, 21 (1950), p 104.

- Frayne, Douglas R. "Sargonic and Gutian Period." The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 2. Univ. of Toronto Press, 1993.

- Gadd, C.J. "The Dynasty of Agade and the Gutian Invasion." Cambridge Ancient History, rev. ed., vol. 1, ch. 19. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1963.

- Grayson, Albert Kirk. Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. J. J. Augustin, 1975; Eisenbrauns, 2000.

- Hallo, W. and J. J. A. Van Dijk. The Exaltation of Inanna. Yale Univ. Press, 1968.

- Jestin, R. Tablettes Sumériennes de Shuruppak, Paris, 1937.

- King, L. W., Chronicles Concerning Early Babylonian Kings, II, London, 1907, pp. 3ff; 87–96.

- Kramer, S. Noah. History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine "Firsts" in Recorded History. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.

- Kramer, S. Noah. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture and Character, Chicago, 1963.

- Levin, Yigal. "Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad." Vetus Testementum 52 (2002).

- Lewis, Brian. The Sargon Legend: A Study of the Akkadian Text and the Tale of the Hero Who Was Exposed at Birth. American Schools of Oriental Research Dissertation Series, No. 4. Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1984.

- Luckenbill, D. D., On the Opening Lines of the Legend of Sargon, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures (1917).

- MacKenzie, Donald A. Myths of Babylonia and Assyria. Gresham, 1900.

- Nougayrol, J. Revue Archeologique, XLV (1951), pp. 169 ff.

- Oates, John. Babylon. London: Thames and Hudson, 1979.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (translator). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3d ed. James B. Pritchard, ed. Princeton: University Press, 1969.

- Parrot, A. Mari, Capitale Fabuleuse, Paris, 1974.

- Parrot, A. Le temple d'Ishtar, Paris, 1956.

- Parrot, A. Les temples d'Ishtarat et de Ninni-zaza, Paris, 1967.

- Poplicha, Joseph. "The Biblical Nimrod and the Kingdom of Eanna." Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 49 (1929), pp. 303–317.

- Postgate, Nichol. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge, 1994.

- Rank, Otto. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero. Vintage Books: New York, 1932.

- Roux, G. Ancient Iraq, London, 1980.

- Sayce, A. H., New Light on the Early History of Bronze, Man, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1921).

- Schomp, Virginia. Ancient Mesopotamia. Franklin Watts, 2005.

- Strange, John. "Caphtor/Keftiu: A New Investigation." Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 102, No. 2 (Apr.–Jun., 1982), pp. 395–396

- Sollberger, E. Corpus des Inscriptions 'Royales' Présargoniques de Lagash, Paris, 1956.

- Van der Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East: ca. 3000–323 BC. Blackwell, 2006.

- Van der Mieroop, Marc., Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History, Routledge, 1999.

- Vandersleyen, Claude. "Keftiu: A Cautionary Note." Oxford Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 22 Issue 2 Page 209 (2003).

- Wainright, G.A. "Asiatic Keftiu." American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 56, No. 4 (Oct., 1952), pp. 196–212.

External links

- Neo-Assyrian Sargon legend

- Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., "The Sargon legend: translation." The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998.

- "Sargon did he exist?"

- Sargon and the Vanishing Sumerians

- Lexicorient article on Sargon