Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes | |

|---|---|

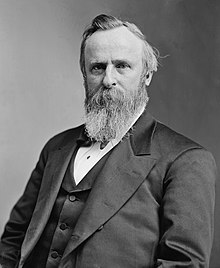

Rutherford B. Hayes, c. 1870–1880, by Mathew Brady | |

| 19th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1881 | |

| Vice President | William A. Wheeler |

| Preceded by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Succeeded by | James A. Garfield |

| 32nd Governor of Ohio | |

| In office January 10, 1876 – March 2, 1877 | |

| Lieutenant | Thomas Lowry Young |

| Preceded by | William Allen |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Lowry Young |

| 29th Governor of Ohio | |

| In office January 13, 1868 – January 8, 1872 | |

| Lieutenant | John C. Lee |

| Preceded by | Jacob Dolson Cox |

| Succeeded by | Edward Follansbee Noyes |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 2nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1865 – July 20, 1867 | |

| Preceded by | Alexander Long |

| Succeeded by | Samuel F. Cary |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 4, 1822 Delaware, Ohio |

| Died | January 17, 1893 (aged 70) Fremont, Ohio |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Lucy Webb Hayes |

| Children | Birchard Austin Hayes James Webb Cook Hayes Rutherford Platt Hayes Joseph Thompson Hayes George Crook Hayes Fanny Hayes Scott Russell Hayes Manning Force Hayes |

| Alma mater | Kenyon College (B.A.) Harvard Law School (LL.B.) |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Brevet Major General |

| Unit | 23rd Regiment, Ohio Volunteer Infantry Kanawha Division |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (October 4, 1822– January 17, 1893) was the 19th President of the United States from March 4, 1877 to March 4, 1881. He also served as the Governor of Ohio twice, from 1868–1872 and 1876–1877.

Hayes was born in Delaware, Ohio, and graduated from Harvard Law School in 1845. He practiced law in Lower Sandusky (now Fremont) and was a city solicitor for Cincinnati 1858–1861. He served in the American Civil War, rising to the rank of major general in 1864. Rutherford Hayes also served in the US Congress 1864–1867 as a Republican before being elected the Governor of Ohio. In 1876 the Republican party nominated Hayes to the office of President.

Though he lost the popular vote, Hayes was elected President by just one electoral vote in the highly disputed election of 1876. Following the early election results, Hayes had believed he lost the election to Democrat Samuel J. Tilden.[1] A congressional commission decided the outcome of the election by awarding Hayes the disputed electoral votes. Historians believe that an informal deal called the Compromise of 1877 was struck between Democrats and Republicans, where the Democrats agreed not to block Hayes from the presidency.

During his presidency, Hayes ordered federal troops to suppress The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and ended Reconstruction by removing troops from the South. After the removal of the Federal troops, all southern states soon returned to Democratic control, signaling the start of the Jim Crow South. On administrative affairs he began gradual civil service reforms and advocated the repeal of the Tenure of Office Act. In foreign policy Hayes renegotiated the Burlingame Treaty with China, granted the army the freedom to intervene in Mexico in order to fight lawless banditos, and nearly saw the construction of a canal across Panama. In 1880 he kept his pledge not to run for a second term and retired quietly to his home in Fremont, Ohio. Later in life he became an active advocate for charity and education during his post-presidency.

Early life

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was born in Delaware, Ohio,[2] on October 4, 1822. His parents were Rutherford Hayes (1787–1822) and Sophia Birchard (1792–1866). His father, a storekeeper, died ten weeks before his birth,[3] making Hayes one of three U.S. presidents born as a posthumous child (Andrew Jackson and Bill Clinton being the others). An uncle, Sardis Birchard, lived with the family and served as Hayes' guardian. Close to Hayes throughout his life, Birchard became a father figure to him, schooling a young Hayes in Latin and Ancient Greek, and contributing much to his early education.[4]

Hayes attended the common schools and the Methodist Academy in Norwalk. He graduated from Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio in August 1842 at the top of his class.[5] He was an honorary member of Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Delta Chi chapter at Cornell), though he had already graduated after the Fraternity Chapter was chartered.[6] After briefly reading the law in Columbus, he graduated in 2 years from Harvard Law School in January 1845. He was admitted to the bar on May 10, 1845, and commenced practice in Lower Sandusky (now Fremont). After dissolving the partnership in Fremont in 1849, he moved to Cincinnati and resumed the practice of law.In 1856, Hayes was nominated for but declined a municipal judgeship; however, in 1858 he accepted an appointment as city solicitor of Cincinnati by the city council and won election outright to that position in 1859, losing a reelection bid in 1860.

Military service

After moving to Cincinnati, Hayes had become a member[7] of a prominent social organization, the Cincinnati Literary Club,[7] whose members included Salmon P. Chase and Edward Noyes, among others. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the Literary Club put together a military company. Hayes was also a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (I.O.O.F).[8] Appointed a major,[5] in the 23rd Regiment, Ohio Volunteer Infantry by Ohio Governor William Dennison Jr.,[3] he originally served as regimental judge-advocate, but was eventually promoted to lieutenant colonel. He proved competent enough at field command that by August 1862, he had been promoted to colonel, receiving command of his original regiment after being wounded in action at the Battle of South Mountain, Maryland, on September 14.

Brevetted to brigadier general in December 1862, he commanded the First Brigade of the Kanawha Division of the Army of West Virginia and turned back several raids. In 1864, Hayes showed gallantry in spearheading a frontal assault and temporarily taking command from George Crook at the Battle of Cloyd's Mountain and continued with Crook on to Charleston. Hayes continued commanding his Brigade during the Valley Campaigns of 1864, participating in such major battles as the Battle of Opequon, the Battle of Fisher's Hill, and the Battle of Cedar Creek.[3] At the end of the Shenandoah campaign, Hayes was promoted to brigadier general in October 1864 and brevetted major general. Although other presidents served in the Civil War, Hayes was the only one who was wounded (five times in all and four horses shot out from under him).[9]

Hayes and McKinley

While commanding the 23rd Regiment of the Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Hayes met William McKinley Jr.,[10] who would later become the 25th President of the United States. The two become fraternal brothers of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.[8] Hayes promoted McKinley twice under his military command, including once for an act of bravery at Antietam. During Hayes' first Ohio gubernatorial race, McKinley engaged in political campaigning and rallying for Hayes' election by "making speeches in the Canton area".[11] Later, as Governor of Ohio, Hayes provided political support for his fellow Republican and Ohioan during McKinley's bid for congressional election.[12]

Early political career

Hayes began political life as a Whig,[13] but in 1853 joined the Free Soil party as a delegate,[14] nominating Salmon P. Chase for Governor of Ohio.[14]

While still in the Shenandoah in 1864, Hayes received the Republican nomination to Congress from Cincinnati. Hayes refused to campaign, stating "I have other business just now. Any man who would leave the army at this time to electioneer for Congress ought to be scalped."[15] Despite this, Hayes was elected and served in the Thirty-ninth and again to the Fortieth Congresses and served from March 4, 1865 to July 20, 1867.

Governor of Ohio

In 1867 Hayes resigned from Congress, having been nominated for Governor of Ohio. The Republican party had nominated Hayes for Governor because of his stance on Reconstruction, which was the main issue of the general election. Hayes and his opponent Allen Thurman battled over whether African Americans should be given the vote. Hayes proclaimed his absolute support for black suffrage and, through the powerful voice of James M. Comly's Ohio State Journal (one of the state's most influential newspapers), went on to win the gubernatorial race.[16] As governor Hayes supported the 15th amendment and reformed state schools and mental hospitals.[17]

He was an unsuccessful candidate in 1872 for election to the Forty-third Congress, and had planned to retire from public life, but was drafted by the Republican convention in 1875 to run for governor again and served from January 1876 to March 2, 1877.[18] Hayes received national notice for leading a Republican sweep of a previously Democratic Ohio government.[19]

Election of 1876

A dark horse nominee (James G. Blaine had led the previous six ballots) by his convention, Hayes became president after the tumultuous, scandal-ridden years of the Grant administration.[20][21] He had a reputation for honesty dating back to his Civil War years.[22] Hayes was noted for his ability not to offend anyone. Henry C. Adams, a prominent political journalist and Washington insider, asserted that Hayes was "a third rate nonentity, whose only recommendation is that he is obnoxious to no one."[23] Because of Hayes' relative anonymity and perceived insignificance, his opponent in the presidential election, Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, was expected to win the presidential election. Tilden won the popular vote by about 250,000 votes, but four states' electoral college votes were contested. To win, the candidates had to muster 185 votes: Tilden was short just one, with 184 votes, Hayes had 165, with 20 votes representing the four states which were contested.[24] To make matters worse, three of these states (Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina) were in the South, which was still under military occupation (the fourth was Oregon). Additionally, historians note, the election was not fair because of the fraud and intimidation perpetrated by both sides.[25][26] A popular phrase of the day called it an election without "a free ballot and a fair count." For the next four years, Democrats would refer to Hayes as "Rutherfraud B. Hayes" for his allegedly illegitimate election because he had lost the popular vote by roughly 250,000 votes.[27]

To decide the results of the election peacefully, the two houses of Congress set up the bi-partisan Electoral Commission to investigate and decide the winner. The Commission consisted of 15 members:7 Democrats, 7 Republicans, and Justice David Davis, an Independent. After his election to the Senate, Davis resigned his seat on the Court and on the Commission. Joseph P. Bradley, a Supreme Court Justice, replaced him. Bradley was a Republican and the commission voted 8 to 7 – along party lines – to award Hayes all the contested electoral votes.[28] Key Ohio Republicans like James A. Garfield and the Democrats, however, agreed at a Washington hotel on the Wormley House Agreement. Southern Democrats were given assurances in the Compromise of 1877 that as President Hayes would appoint one southerner to his cabinet, pull federal troops out of the South, and end Reconstruction.[29] The agreement restored Democratic control of the Southern states, ending much of the national government's role in Reconstruction.

Presidency

Because March 4, 1877 was a Sunday, Hayes took the oath of office in the Red Room of the Executive Mansion,[30] becoming the first president to take the oath of office in the White House. This ceremony was held in secret, because the previous year's election was so divisive that outgoing President Grant feared an insurrection by Tilden's supporters and wanted to ensure that any Democratic attempt to hijack the public inauguration ceremony would fail.[30] Hayes took the oath again publicly on March 5, 1877 on the East Portico of the United States Capitol, and served until March 4, 1881. Hayes' best known quotation, "He serves his party best who serves his country best," is from his 1877 Inaugural Address.[31] Above all, Hayes intended for his Inaugural Address to soothe the wounds of a nation still scarred from the Civil War. With the phrase: "forever wipe out in our political affairs the color line and the distinction between North and South, to the end that we may have not merely a united North or a united South, but a united country..." Hayes signaled the end of the Reconstruction Era.[32]

End of Reconstruction and civil rights

The single most important issue facing the new Hayes administration was Reconstruction, the period after the Civil War where the South was rebuilt under primarily Republican state governments. Radical Reconstruction had been the hallmark of Republican policies since 1868, but it was already nearing its end when Hayes was running for the Presidency. In Congress Hayes had supported Radical Reconstruction. As Governor of Ohio, Hayes had approved of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which banned racial discrimination at the polls.[32] Yet Hayes succumbed to the feelings of the American public at the time. On election day "only Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina had Republican governments."[32] By Hayes' Inauguration Florida had already fallen to a Democratic state government. The crumbling of Republican governments in the South signified the end of Reconstruction as the military could neither police southern states nor maintain Republican control.[32][33][34] In fact, much of the military was occupied with the Indian Wars in the West and so the Federal government's ability to maintain Reconstruction was already severely limited by the time of Hayes' presidency.[32] Besides the troubling military situation, Hayes also faced a Democratic House of Representatives that refused to fund Reconstruction. Hayes also could not turn to Northern voters for support; most Northerners were concerned with the economy, not Reconstruction.[32] Under such circumstances "the question Hayes faced was not whether the troops should be removed but when they would be removed."[32]

Hayes believed that southern whites, motivated by paternalism, would protect the rights of African Americans if given back control of state governments.[35][36][37] Hayes wanted to assimilate African Americans into white society with paternalistic protection by encouraging the growth of Republican Reconstruction ideals in states that were reluctant to enforce civil rights.[37] Hayes did not regard making deals with Democrats as abandoning the civil rights agenda for African Americans because he thought "bayonet rule" would fail.[38] In 1880, the last year of his presidency, Hayes wrote in his diary an examination of his role in Reconstruction: "My task was to wipe out the color line, to abolish sectionalism, to end the war and bring peace." [39] Hayes then defended his actions in regards to reconstruction insisting that "It is not true that tried Republicans at the South were totally abandoned."[39] Hayes was truly shocked by the old confederate officers who returned to power in the form of the Democratic party. He believed they would uphold the paternalistic ideal he had tried to imbue in the southern states.[40] That perceived betrayal became the biggest disappointment of his Presidency. Many historians consider the withdrawal of federal troops as "the great betrayal" to African Americans. Without federal protection, African American voters faced discrimination and intimidation at the polls. Under the Hayes administration "Jim Crow" laws spread around the country, closing the book on racial equality for another 100 years.[41]Though he ended Reconstruction, Hayes did veto bills repealing civil rights enforcement four times before finally signing one that satisfied his requirement for black rights.[33]

Civil service reform

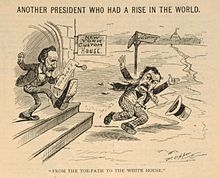

At the time of Hayes' Inauguration a new political issue was heating up – Civil Service Reform. Since the administration of Andrew Jackson the Spoils System, where politicians gave government appointments to supporters, had reigned in Washington. Hayes, taking a moderate stance, decided that reforms had to be made, especially with the memory of the Grant Administration scandals still vivid. Hayes found himself in a very delicate position. His moderate stance annoyed reformers, who felt he was not going far enough, and infuriated the Spoils System Republicans. The faction of the Republican party associated most closely with the Spoils System was the 'Stalwarts.' Hayes' goal was to "depoliticize the civil service" without "destroy[ing] Republican party organizations."[32] Braving the political climate, Hayes issued an executive order that forbade federal office holders from taking part in party politics and protected them from receiving party contributions. When Hayes enforced this order at the New York Customs House, the nation's largest revenue collection agency, it created conflict with Senator Roscoe Conkling, who controlled civil service appointments in New York state and lead the "Stalwarts". Hayes had two goals: a) clean up corruption in the customhouse and b) remove some of Conkling's political power. Conkling had been a political rival during the 1876 election and Hayes wanted to curb much of Conkling's influences.[32][42] Hayes realized that he would have to end the unwritten rule of "courtesy of the Senate" where Senators appointed men to government positions in their states. During a congressional recess Hayes sacked Chester A. Arthur and his second-in-command and replaced them with Edwin A. Merritt, a rival of Conkling, and Silas W. Burt, a strong reformer, respectively.[43] The victory for the President was made more remarkable by the political climate of the time. Since Andrew Johnson's presidency Congress had asserted more and more power. [37]By standing up to Conkling and his political machine, Hayes had expanded the power of the presidency and paved the way for the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 (ironically Arthur would sign the Act into law just 5 years after being sacked).[44][45]

Domestic policy

Hayes' most controversial domestic act– apart from ending Reconstruction– was his response to the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Employees of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad[46] walked off the job and were joined across the country by thousands of workers in the railroad industry. When the labor disputes exploded into riots in several cities, Hayes called in federal troops, who, for the first time in U.S. history, fired on the striking workers, killing more than 70. Although the troops eventually managed to restore the peace, working people and industrialists alike were displeased with the military intervention.[47]

On the economic front Hayes had to deal with monetary concerns still left over from the Civil War. In order to pay for the war, the US government had issued Greenbacks or paper money not backed by specie (gold or silver). Debtors (generally farmers in the Mid-west and West) wanted to increase the circulation of Greenbacks because the resulting inflation would decrease their debts.[32][48] Creditors (generally Eastern industrialists and bankers) wanted to put the US back on the gold standard. Hayes came to believe that a hard money policy (returning to the Gold standard) would ensure prosperity and so he fully supported the 1875 Specie Resumption Act.[49] Hayes' administration gradually increased the government's supply of gold.[50] By 1879 the Greenback was attached to the value of gold. The economic boom that followed the Panic of 1873 is credited to the return to the Gold standard along with good fortune.[32]

Perhaps one of the biggest political challenges Hayes ever faced in his administration was the so called "Battle of the Riders".[51] In the elections of 1878 the Democrats captured control of both houses of Congress. The Democrats, in an effort to strengthen their chances in the 1880 elections, began adding riders – pieces of legislation that "ride" to passage on another bill – to necessary appropriations bills. The Democrats' riders targeted federal election enforcement laws that prevented fraud and voter intimidation. Determined not to give in, Hayes vetoed the bills with the riders citing two reasons: a) every citizen has the right "to cast one unintimidated ballot and to have his ballot honestly counted" [32] and b) "the riders were an unconstitutional attempt to force legislation on the President."[32] The Democrats could not overcome Hayes' vetoes and eventually gave up the fight. Their efforts also backfired because Hayes' tenacity had united the Republicans heading into the 1880 elections.[32] The "Battle of the Riders" thus ended with a victory for presidential power.

Foreign policy

In 1878, Hayes was asked by Argentina to act as arbitrator following the War of the Triple Alliance between Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay.[52] The Argentines hoped that Hayes would give them the Gran Chaco region; however, he decided in favor of the Paraguayans.[53] His decision made him a hero in Paraguay, and a city (Villa Hayes) and a department (Presidente Hayes) were named in his honor.[53] Schools, roads, a soccer team (the Los Yanquis, Spanish for the Yankees), and a regional historical museum are named for him.[53]

A significant foreign policy issue during Hayes' tenure was the possibility of a French constructed canal across the Isthmus of Panama (which was then under Colombian control). The French plans were designed by Ferdinand de Lesseps, who played a key role in the construction of the Suez Canal. Hayes was suspicious about the French project, especially since little more than a decade had elapsed since Napoleon III tried to install Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico.[54] In a message delivered to Congress Hayes clarified his stance on the canal issue: "The policy of this country is a canal under American control. The United States cannot consent to the surrender of this control to any European power ..."[55] The French-designed canal was delayed for political reasons, including the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, and went bankrupt by 1888.[55] A canal across Panama would be built under American control years later under Theodore Roosevelt.

The Hayes administration also faced foreign policy pressure because of immigration. In 1868 the US had ratified the Burlingame Treaty with China,[56] allowing an unrestricted flow of Chinese immigrants into the country.[54] Immigration problems soon resulted. After the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, cheap Eastern goods flowed out West, forcing western manufacturers to cut costs by employing chinese laborers who worked for less than their white counterparts.[54] By the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, anti-immigration sentiment in California had escalated into riots. The Workingmen's Party of California even called for the government to "stop the leprous Chinamen from landing." [54] Anti-immigration political movements then petitioned Congress to block more chinese immigration which Congress subsequently resolved to do. Hayes, however, promptly vetoed the bill because it violated the Burlingame Treaty. Such action earned Hayes the consternation of many white Americans living on the West Coast.[54]

Hayes, however, ultimately gave in to anti-immigration sentiment. His administration decided that the Burlingame Treaty should be revised and in 1880[57] the treaty commision had negotiated new immigration and commerce terms.[57] The new treaty allowed the United states to "regulate, limit, and suspend, but not prohibit the coming of Chinese laborers."[54] The US government would eventually use that power in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1883.

The Hayes administration was also very involved in Mexican affairs. Throughout the 1870s the US-Mexico border was a hotspot of violence caused by "lawless bands."[54] Only three months after his Inauguration, Hayes granted the Army the power to pursue outlaws, even if they crossed into Mexican territory.[58] Despite angry rhetoric emanating from Porfirio Diaz (then the dictator of Mexico), Mexican officials decided to jointly pursue bandits. After three years Hayes revoked the order, citing the decrease in violence along the border.[59]

Notable legislation

Other acts include:

- Desert Land Act (1877)

- Bland-Allison Act (1878)

- Timber and Stone Act (1878)

Significant events

- Munn v. Illinois (1876)

- Installation of the first telephone in the White House[60]

- Great Railroad Strike (1877)

- Yellow Fever Outbreak (1878)

Administration and Cabinet

| The Hayes cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Rutherford B. Hayes | 1877–1881 |

| Vice President | William A. Wheeler | 1877–1881 |

| Secretary of State | William M. Evarts | 1877–1881 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | John Sherman | 1877–1881 |

| Secretary of War | George W. McCrary | 1877–1879 |

| Alexander Ramsey | 1879–1881 | |

| Attorney General | Charles Devens | 1877–1881 |

| Postmaster General | David M. Key | 1877–1880 |

| Horace Maynard | 1880–1881 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Richard W. Thompson | 1877–1880 |

| Nathan Goff, Jr. | 1881 | |

| Secretary of the Interior | Carl Schurz | 1877–1881 |

Supreme Court appointments

Hayes appointed two Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States:

- John Marshall Harlan– 1877

- William Burnham Woods– 1880

Post-Presidency

Hayes decided not to seek re-election in 1880, keeping his pledge that he would not run for a second term.[61]He had, in his inaugural address, proposed a one-term limit for the presidency combined with an increase in the term length to six years.

Hayes became an active advocate for charity during his post-presidency. Hayes believed that in retirement he must "promote the welfare and the happiness of his family, his town, his State, and his country."[62] For Hayes the greatest service was to educate America. Hayes felt that "the American government could be no better than its people and that its people could be improved morally and materially by education."[62] Hayes began trust funds that purposed to educate poor southern whites and blacks. In addition Hayes was a crusader for federal education subsidies for all children, regardless of race.[62] Hayes' wish was that better education would "improve the economic status of the poor, would enlighten the intolerant, and provide the fair start in life envisioned by Lincoln – and the political equality declared by Jefferson – as part of everyone's birthright."[62]

In line with his reforming attitude, Hayes crusaded for better prison conditions and the abolishment of the death penalty.[62] Hayes was moved to embrace prison reform because he felt that all prisoners could be redeemed and that crime was caused by poverty.[63] In retirement Hayes was troubled by the disparity between the rich and the poor.[62] Hayes also served on the Board of Trustees of The Ohio State University, the school he helped found during his time as governor of Ohio, from the end of his Presidency until his death.

Though Hayes adored his Spiegel Grove estate, he was greatly saddened by his wife's death in 1889. He wrote that "the soul had left [Spiegel Grove]" when she died.[62] After Lucy's death Hayes' daughter, Fanny, became his companion. Fanny reported that "her father never travel[ed] without several pictures of Lucy."[62]

Rutherford Birchard Hayes died of complications of a heart attack in Fremont, Sandusky County, Ohio, at 12:00 p.m. on Tuesday January 17, 1893. His last words were "I know that I'm going where Lucy [Hayes' wife] is."[64] A funeral procession led by President Grover Cleveland and Ohio Governor William McKinley, a future president, followed Hayes' body until he was interned in Oakwood Cemetery.[65] Following the gift of his home to the state of Ohio for the Spiegel Grove State Park, he was re-interred there in 1916.

Family

Hayes was the youngest of four children. Two of his siblings, Lorenzo Hayes (1815–1825) and Sarah Sophia Hayes (1817–1821), died in childhood, as was common then. Hayes was close to his surviving sibling, Fanny Arabella Hayes (1820–1856), as can be seen in this diary entry, written just after her death:

- July, 1856. My dear only sister, my beloved Fanny, is dead! The dearest friend of childhood, the affectionate adviser, the confidante of all my life, the one I loved best, is gone; alas! never again to be seen on earth.[66]

With Lucy Ware Webb, Hayes had the following children:

- Birchard Austin Hayes (1853–1926)

- James Webb Cook Hayes (1856–1934)

- Rutherford Platt Hayes (1858–1927)

- Joseph Thompson Hayes (1861–1863)

- George Crook Hayes (1864–1866)

- Fanny Hayes (1867–1950)

- Scott Russell Hayes (1871–1923)

- Manning Force Hayes (1873–1874)

Writings and speeches

Monday, March 5, 1877 Inaugural Address:

I shall not undertake to lay down irrevocably principles or measures of administration, but rather to speak of the motives which should animate us, and to suggest certain important ends to be attained in accordance with our institutions and essential to the welfare of our country.[31]

Many of the calamitous efforts of the tremendous revolution which has passed over the Southern States still remain. The immeasurable benefits which will surely follow, sooner or later, the hearty and generous acceptance of the legitimate results of that revolution have not yet been realized. Difficult and embarrassing questions meet us at the threshold of this subject.[31]

With respect to the two distinct races whose peculiar relations to each other have brought upon us the deplorable complications and perplexities which exist in those States, it must be a government which guards the interests of both races carefully and equally.[31]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- Historical rankings of United States Presidents

- List of Presidents of the United States

- U.S. Presidents on U.S. postage stamps

References

- ^ Hoogenboom, Ari. Rutherford B. Hayes: warrior and president. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. 1995. p 276.

- ^ "In memoriam." Catalogue of Ohio Wesleyan University for ..., Delaware, Ohio . 1890. p 130.

- ^ a b c "Biography of Rutherford B. Hayes". Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

- ^ Trefousse, Hans. Rutherford B. Hayes. New York: Times Books, 2002. p 4.

- ^ a b "Rutherford B. Hayes". American Presidents: Life Portraits. National Cable Satellite Corporation. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

- ^ DeSantis, Alan. Inside Greek U.Lexington :University Press of Kentucky. 2007. p 8.

- ^ a b "Rutherford B. Hayes". Ohio History Central. July 1, 2005. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

- ^ a b "Notable Members". Independent Order of Odd Fellows. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

- ^ Heidler, David, Jeanne Heidler, and David Coles. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002. p 957.

- ^ "William McKinley". The Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

- ^ Walters, Everett. (July 26, 2005.) "William McKinley". The Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

- ^ Morgan, Howard. William McKinley and his America. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. 2003. p 43.

- ^ "Rutherford B. Hayes ." Our Presidents. Washington, DC: WhiteHouse.gov. Retrieved on August 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Conwell, Russell. Life and public services of Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes. Boston: B. B. Russell, 1876. pp 129-130.

- ^ Our Presidential Candidates and Political Compendium Also Containing Lives of the Candidates for VI. New York: BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2009. p 196.

- ^ "Rutherford B. Hayes". Ohio History Central. July 1, 2005. Retrieved on August 22, 2010.

- ^ Williams, Charles, and William Smith. The life of Rutherford Birchard Hayes. 2 vols. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1914. p 346.

- ^ "Rutherford Birchard Hayes." Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events. Vol 18. D. Appleton & Co. 1894. p 388.

- ^ "The Political Campaign of 1875 in Ohio." Ohio history. Vol 31. Columbus: Ohio Historical Society. 1922. p 57.

- ^ Crapol, Edward. James G. Blaine: architect of empire. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. 2000. p 45.

- ^ Murrin, John, and Paul E. Johnson, James M. McPherson, Gary Gerstle, Emily S. Rosenberg. Liberty, Equality, Power, A History of the American People: To 1877. Florence, KY: Cengage Learning. 2008. p 452.

- ^ Trefousse 2002, 69.

- ^ Ackerman, Kenneth. Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield. NewYork: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004. p 44.

- ^ Woodward, C. Vann. Reunion and reaction: the compromise of 1877 and the end of reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. pp 317—318.

- ^ Ruggiero, Adriane. Reconstruction. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish. 2006. p 85.

- ^ Haworth, Paul. The Hayes-Tilden disputed presidential election of 1876. Cleveland: Burrows Brothers Company. 1906. p 330.

- ^ Morris, Roy, and Roy Jr. Morris. Fraud of the Century. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2004. p 2.

- ^ Beatty, Jack. Age of Betrayal: The Triumph of Money in America, 1865-1900. New York: Random House, INC. 2008. p 261.

- ^ Woodward 1991, 3–4.

- ^ a b "1877 Rutherford B. Hayes." U.S. Senate Art & History. United States Senate. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Hayes, Rutherford. "Inaugural Address." Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents of the United States. Bartleby.com, 1989. Retrieved on August 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bahles, Gerald. "Rutherford B. Hayes: Domestic Affairs." Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Trefousse 2002, 90.

- ^ Ferrell, Claudine. Reconstruction. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. p 61.

- ^ Cooper, William, and Thomas Terrill. The American South: a history. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. 2008. p 446.

- ^ Alston, Lee, and Joseph Ferrie. Southern paternalism and the American welfare state. Cambridge University Press. 1999. p 2.

- ^ a b c Edward Herrmann (Narrator) (2005). The Presidents (Television Production). History Channel.

- ^ Slap, Andrew. The doom of Reconstruction: the liberal Republicans in the Civil War era. New York: Fordham University Press, 2006. p 239.

- ^ a b "Volume III Chapter XXXVIII." Ohio Historical Society. September 10, 2009.

- ^ Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's unfinished revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper Collins, 2002. p 582.

- ^ Logan, Rayford. The betrayal of the Negro, from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson. Cambridge:Da Capo Press. 1997. pp 12—13.

- ^ Trefousse 2002, 93.

- ^ Williams and Smith 1914, 86.

- ^ Calabresi, Steven, and Christopher Yoo. The unitary executive: presidential power from Washington to Bush. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 2008. pp 199—201

- ^ Jewell, Elizabeth. U.S. Presidents Factbook. New York: Random House, Inc. 2007. p 1877.

- ^ "Great Railroad Strike of 1877." Ohio History Central. Columbus, OH: Ohio Historical Society, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Perry, Elisabeth, and Smith, Karen. The Gilded Age and Progressive Era: a student companion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. p 291.

- ^ Conlin, Joseph. The American Past: A Survey of American History. 9th ed. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010. p 427.

- ^ Berkey, William. The money question: The legal tender paper monetary system of the United States. New York: W.W. Hart, 1876. p 279.

- ^ Timberlake, Richard. Monetary policy in the United States: an intellectual and institutional history. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. p 113.

- ^ Vazzano, Frank. "President Hayes, Congress and the Appropriations Riders Vetoes ." Congress & the Presidency. 20.1 (1993): pp 25–37.

- ^ Hodge, Carl, and Cathal Nolan. US Presidents and foreign policy. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. 2007. p 155.

- ^ a b c Hodge and Nolan 2007, 155

- ^ a b c d e f g Bahles, Gerald. "Rutherford B. Hayes: Foreign Affairs." Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Hodge and Nolan 2007, 154

- ^ Hu, Sen. The Rocky Road to Liberty: A Documented History of Chinese Immigration and Exclusion. Saratoga, CA: Javvin Press, 2010. p 152.

- ^ a b Callahan, James. "Diplomatic Relations with China." Encyclopedia Americana. 6. (1918): p 534.

- ^ Levy, Debbie. Rutherford B. Hayes. Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-first Century Books, 2007. p 83.

- ^ Barker, Eugene, and Herbert Bolton. "The Hayes Administration and Mexico." Southwestern historical quarterly. 24. July 1920. pp 151—153.

- ^ Young, Bev. Presidential cookies: cookie recipes of the Presidents of the United States. Sacramento, CA: Presidential Publishing, 2005. p 67.

- ^ Van Doren, Charles, and Robert McHenry. "Rutherford Birchard Hayes." Webster's guide to American history. New York: Merriam Webster. 1971. p 1011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bahles, Gerald. "Rutherford B. Hayes: Life After the Presidency." Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Williams and Smith 1914, 347–348.

- ^ Paletta, Lu Ann, and Fred Worth. World Almanac of presidential facts. New Delhi: Pharos Books. 1993. p 90.

- ^ "The Hayes Memorial." Ohio archaeological and historical quarterly. 26. April 1919. p 509.

- ^ Hayes, Rutherford. Diary and Letters of Rutherford Birchard Hayes: 1834-1860. Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. 1922. p 498.

External links

- United States Congress. "Rutherford B. Hayes (id: H000393)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2008-10-19

- Rutherford B. Hayes: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Essays on Rutherford Hayes, each member of his cabinet, and the First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- [1] Sort the presidents by several facts

- Inaugural Address

- The Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center, Fremont, Ohio

- White House Biography

- Diary and Letters of Rutherford B. Hayes

- Works by Rutherford B. Hayes at Project Gutenberg

- Rutherford B. Hayes at Find a Grave Retrieved on 2008-02-12

- Hayes 1893 New York Times obituary

- Rutherford B. Hayes

- American solicitors

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Governors of Ohio

- Harvard Law School alumni

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Kenyon College alumni

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio

- Ohio Republicans

- People from Delaware County, Ohio

- People from Sandusky County, Ohio

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- Republican Party (United States) presidential nominees

- American people of Scottish descent

- United States presidential candidates, 1876

- Union Army generals

- 1822 births

- 1893 deaths

- Odd Fellows

- Presidents of the United States