Banana

| Banana | |

|---|---|

Banana 'tree' (Musa acuminata 'Lacatan'). Illustration from the 1880 book Flora de Filipinas by Francisco Manuel Blanco | |

| Hybrid parentage | Musa acuminata × Musa balbisiana Colla 1820 |

| Cultivar group | See Banana Cultivar Groups |

| Origin | Southeast Asia, South Asia |

Banana is the common name for herbaceous plants of the genus Musa and for the fruit they produce. Bananas come in a variety of sizes and colors when ripe, including yellow, purple, and red.

Almost all modern edible parthenocarpic bananas come from the two wild species Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. The scientific names of bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana or hybrids Musa acuminata × balbisiana, depending on their genomic constitution. The old scientific names Musa sapientum and Musa paradisiaca are no longer used.

Banana is also used to describe the edible fruits of the Fe'i bananas and Ensete, neither of which properly belong to the Musa genus. The taxonomy of Fe'i-type cultivars is hard to determine; and Ensete, though belonging to the same family (Musaceae), is part of a different genus.

In popular culture and commerce, "banana" usually refers to soft, sweet "dessert" bananas. By contrast, Musa cultivars with firmer, starchier fruit are called plantains. The distinction is purely arbitrary and the terms 'plantain' and 'banana' are sometimes interchangeable depending on their usage.

They are native to tropical South and Southeast Asia, and are likely to have been first domesticated in Papua New Guinea.[1] Today, they are cultivated throughout the tropics.[2] They are grown in at least 107 countries,[3] primarily for their fruit, and to a lesser extent to make fiber, banana wine and as ornamental plants.

Description

The banana plant is the largest herbaceous flowering plant.[4] The plants are normally tall and fairly sturdy and are often mistaken for trees, but their main or upright stem is actually a pseudostem that grows 6 to 7.6 metres (20 to 25 feet) tall, growing from a corm. Each pseudostem can produce a single bunch of bananas. After fruiting, the pseudostem dies, but offshoots may develop from the base of the plant. Many varieties of bananas are perennial.

Leaves are spirally arranged and may grow 2.7 metres (8.9 feet) long and 60 cm (2.0 ft) wide.[5] They are easily torn by the wind, resulting in the familiar frond look.[6]

Each pseudostem normally produces a single inflorescence, also known as the banana heart. (More are sometimes produced; an exceptional plant in the Philippines produced five.)[7] The inflorescence contains many bracts (sometimes incorrectly called petals) between rows of flowers. The female flowers (which can develop into fruit) appear in rows further up the stem from the rows of male flowers. The ovary is inferior, meaning that the tiny petals and other flower parts appear at the tip of the ovary.

The banana fruits develop from the banana heart, in a large hanging cluster, made up of tiers (called hands), with up to 20 fruit to a tier. The hanging cluster is known as a bunch, comprising 3–20 tiers, or commercially as a "banana stem", and can weigh from 30–50 kilograms (66–110 lb). In common usage, bunch applies to part of a tier containing 3-10 adjacent fruits.

Individual banana fruits (commonly known as a banana or 'finger') average 125 grams (0.276 lb), of which approximately 75% is water and 25% dry matter. There is a protective outer layer (a peel or skin) with numerous long, thin strings (the phloem bundles), which run lengthwise between the skin and the edible inner portion. The inner part of the common yellow dessert variety splits easily lengthwise into three sections that correspond to the inner portions of the three carpels.

The fruit has been described as a "leathery berry".[8] In cultivated varieties, the seeds are diminished nearly to non-existence; their remnants are tiny black specks in the interior of the fruit. Bananas grow pointing up, not hanging down.

Bananas are naturally slightly radioactive,[9] more so than most other fruits, because of their high potassium content, and the small amounts of the isotope potassium-40 found in naturally occurring potassium.[10] Proponents of nuclear power sometimes refer to the banana equivalent dose of radiation to support their arguments.[11]

Taxonomy

The genus Musa is in the family Musaceae. The APG II system, of 2003 (unchanged from 1998), assigns Musaceae to the order Zingiberales in the clade commelinids in the monocotyledonous flowering plants. Some sources assert that the banana's genus, Musa, is named for Antonio Musa, physician to the Emperor Augustus.[12] Others say that Linnaeus, who named the genus in 1750, simply adapted an Arabic word for banana, mauz.[13] The word banana itself might have come from the Arabic banan, which means "finger",[13] or perhaps from Wolof banaana.[14] The genus contains many species; several produce edible fruit, while others are cultivated as ornamentals.[15]

Banana classification has long been a problematic issue for taxonomists due to the way Linnaeus originally classified bananas as two species based only on their methods of consumption, Musa sapientum for dessert bananas and Musa paradisiaca for plantains. However, this simplistic classification has proved to be inadequate to address the sheer number of cultivars (a lot of them synonymous) existing in its primary center of diversity, Southeast Asia.[16]

Ernest Cheesman first discovered that Musa sapientum and Musa paradisiaca, described by Linnaeus, were actually cultivars and descendants of two wild and seedy species, Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana, both first described by Luigi Aloysius Colla.[17] He recommended their abolition in favor of reclassifying bananas according to three morphologically distinct cultivars - those primarily exhibiting the botanical characteristics of Musa balbisiana, those primarily exhibiting the botanical characteristics of Musa acuminata, and those with characteristics that are the combination of the two.[16]

Researchers Norman Simmonds and Ken Shepherd proposed the genome-based nomenclature system in 1955. This system eliminated almost all the difficulties and inconsistencies of the nomenclature system of bananas based on Musa sapientum and Musa paradisiaca. Despite this, Musa paradisiaca is still recognized by some authorities today, leading to confusion.[17][18]

Generally, modern classifications of banana cultivars follow Simmonds' and Shepherd's system. The accepted names for bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana or Musa acuminata × balbisiana, depending on their genetic ancestry.

Synonyms include:

- Musa × sapientum L.

- Musa paradisiaca L.

- Musa × paradisiaca L.

- Musa paradisiaca L. subsp. Musa sapientum J. G. Baker

- Musa rosacea N. J. von Jacquin

- Musa violacea J. G. Baker

- Musa cliffortiana L.

- Musa dacca P. F. Horaninow

- Musa rosacea N. J. von Jacquin

- Musa × paradisiaca L. subsp. sapientum(L.) C. E. O. Kuntze

- Musa × paradisiaca var. dacca (P. F. Horaninow) J. G. Baker ex K. M. Schumann

For the banana cultivar previously referred to as Musa sapientum, see Latundan Banana.[19] For bananas and plantains previously referred to as Musa paradisiaca, see Plantain.[17]

For a list of the cultivars classified under the new system see Banana Cultivar Groups.

| Comparison between the two wild banana ancestors in the Simmonds and Shepherd table (1955) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Species | Musa acuminata | Musa balbisiana |

| Color of pseudostem | Black or grey-brown spots | Unmarked or slightly marked |

| Petiole canal | Erect edge, with scarred inferior leaves, not against the pseudostem | Closed edge, without leaves, against the pseudostem |

| Stalk | Covered with fine hair | Smooth |

| Pedicels | Short | Long |

| Ovum | Two regular rows in the locule | Four irregular rows in the locule |

| Elbow of the bract | Tall (< 0.28) | Short (> 0.30) |

| Bend of the bract | The bract wraps behind the opening | The bract raises without bending behind the opening |

| Form of the bract | Lance- or egg-shaped, tapering markedly after the bend | Broadly egg-shaped |

| Peak of the bract | Acute | Obtuse |

| Color of the bract | Dark red or yellow on the outside, opaque purple or yellow on the inside | Brown-purple on the outside, crimson on the inside |

| Discoloration | The inside of the bract is more bright toward the base | The inside of the bract is uniform |

| Scarification of the bract | Prominent | Not prominent |

| Free tepal of the male flower | Corrugated under the point | Rarely corrugated |

| Color of the male flower | White or cream | Pink |

| Color of the markings | Orange or bright yellow | Cream, yellow, or pale pink |

Historical cultivation

Early cultivation

Southeast Asian farmers first domesticated bananas. Recent archaeological and palaeoenvironmental evidence at Kuk Swamp in the Western Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea suggests that banana cultivation there goes back to at least 5000 BCE, and possibly to 8000 BCE.[1] It is likely that other species were later and independently domesticated elsewhere in southeast Asia. Southeast Asia is the region of primary diversity of the banana. Areas of secondary diversity are found in Africa, indicating a long history of banana cultivation in the region.

Phytolith discoveries in Cameroon dating to the first millennium BCE[21] triggered an as yet unresolved debate about the date of first cultivation in Africa. There is linguistic evidence that bananas were known in Madagascar around that time.[22] The earliest prior evidence indicates that cultivation dates to no earlier than late 6th century AD.[23] It is likely, however, that bananas were brought at least to Madagascar if not to the East African coast during the phase of Malagasy colonization of the island from South East Asia c400CE.[24]

The Buddhist story Vessantara Jataka briefly mention about banana, the king Vessantara has found a banana tree (among some other fruit trees) in the jungle, that bear bananas of the size of an elephants tusk.

The banana may have been present in isolated locations of the Middle East on the eve of Islam. There is some textual evidence that the prophet Muhammad was familiar with bananas. The spread of Islam was followed by far-reaching diffusion. There are numerous references to it in Islamic texts (such as poems and hadiths) beginning in the 9th century. By the 10th century the banana appears in texts from Palestine and Egypt. From there it diffused into north Africa and Muslim Iberia. During the medieval ages, bananas from Granada were considered among the best in the Arab world.[20] In 650, Islamic conquerors brought the banana to Palestine. Nowadays, banana consumption increases significantly in Islamic countries during Ramadan, the month of daylight fasting.

Bananas were introduced to the Americas by Portuguese sailors who brought the fruits from West Africa in the 16th century.[25] The word banana is of West African origin, from the Wolof language, and passed into English via Spanish or Portuguese.[26]

Many wild banana species as well as cultivars exist in extraordinary diversity in New Guinea, Malaysia, Indonesia, China, and the Philippines.

There are fuzzy bananas whose skins are bubblegum pink; green-and-white striped bananas with pulp the color of orange sherbet; bananas that, when cooked, taste like strawberries. The Double Mahoi plant can produce two bunches at once. The Chinese name of the aromatic Go San Heong banana means 'You can smell it from the next mountain.' The fingers on one banana plant grow fused; another produces bunches of a thousand fingers, each only an inch long.

— Mike Peed, The New Yorker[27]

Plantation cultivation

In the 15th and 16th century, Portuguese colonists started banana plantations in the Atlantic Islands, Brazil, and western Africa.[28] As late as the Victorian Era, bananas were not widely known in Europe, although they were available.[28] Jules Verne introduces bananas to his readers with detailed descriptions in Around the World in Eighty Days (1872).

In the early 20th century, bananas formed the basis of large commercial empires, exemplified by the United Fruit Company, which created immense plantations especially in Central and South America. These were usually commercially exploitative, and the term "Banana republic" was coined for states like Honduras and Guatemala, representing the fact that these companies and their political backers created and abetted "servile dictatorships" whose primary motivation was to protect the companies.[29]

Modern cultivation

All widely cultivated bananas today descend from the two wild bananas Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. While the original wild bananas contained large seeds, diploid or polyploid cultivars (some being hybrids) with tiny seeds are preferred for human raw fruit consumption.[30] These are propagated asexually from offshoots. The plant is allowed to produce 2 shoots at a time; a larger one for immediate fruiting and a smaller "sucker" or "follower" to produce fruit in 6–8 months. The life of a banana plantation is 25 years or longer, during which time the individual stools or planting sites may move slightly from their original positions as lateral rhizome formation dictates.

Cultivated bananas are parthenocarpic, which makes them sterile and unable to produce viable seeds. Lacking seeds, propagation typically involves removing and transplanting part of the underground stem (called a corm). Usually this is done by carefully removing a sucker (a vertical shoot that develops from the base of the banana pseudostem) with some roots intact. However, small sympodial corms, representing not yet elongated suckers, are easier to transplant and can be left out of the ground for up to 2 weeks; they require minimal care and can be shipped in bulk.

It is not necessary to include the corm or root structure to propagate bananas; severed suckers without root material can be propagated in damp sand, although this takes somewhat longer.

In some countries, commercial propagation occurs by means of tissue culture. This method is preferred since it ensures disease-free planting material. When using vegetative parts such as suckers for propagation, there is a risk of transmitting diseases (especially the devastating Panama disease).

As a non-seasonal crop, bananas are available fresh year-round.

Cavendish

In global commerce, by far the most important cultivars belong to the triploid AAA group of Musa acuminata, commonly referred to as Cavendish group bananas. They account for the majority of banana exports.[30] The cultivars Dwarf Cavendish and Grand Nain (Chiquita Banana) gained popularity in the 1950s after the previous mass-produced cultivar, Gros Michel (also an AAA group cultivar), became commercially unviable due to Panama disease, a fungus which attacks the roots of the banana plant.[30]

Ease of transport and shelf life rather than superior taste make the Dwarf Cavendish the main export banana.

Even though it is no longer viable for large scale cultivation, Gros Michel is not extinct and is still grown in areas where Panama disease is not found.[citation needed] Likewise, Dwarf Cavendish and Grand Nain are in no danger of extinction, but they may leave supermarket shelves if disease makes it impossible to supply the global market. It is unclear if any existing cultivar can replace Cavendish bananas, so various hybridisation and genetic engineering programs are attempting to create a disease-resistant, mass-market banana.[30]

Ripening

Export bananas are picked green, and ripen in special rooms upon arrival in the destination country. These rooms are air-tight and filled with ethylene gas to induce ripening. The vivid yellow color normally associated with supermarket bananas is in fact a side effect of the artificial ripening process.[citation needed] Flavor and texture are also affected by ripening temperature. Bananas are refrigerated to between 13.5 and 15 °C (56.3 and 59.0 °F) during transport. At lower temperatures, ripening permanently stalls, and turns the bananas gray as cell walls break down. The skin of ripe bananas quickly blackens in the 4 °C (39 °F) environment of a domestic refrigerator, although the fruit inside remains unaffected.

"Tree-ripened" Cavendish bananas have a greenish-yellow appearance which changes to a brownish-yellow as they ripen further. Although both flavor and texture of tree-ripened bananas is generally regarded as superior to any type of green-picked fruit,[citation needed] this reduces shelf life to only 7–10 days.

Bananas can be ordered by the retailer "ungassed", and may show up at the supermarket fully green. "Guineo Verde", or green bananas that have not been gassed will never fully ripen before becoming rotten. Instead of fresh eating, these bananas are best suited to cooking, as seen in Mexican culinary dishes.

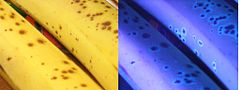

A 2008 study reported that ripe bananas fluoresce when exposed to ultraviolet light. This property is attributed to the degradation of chlorophyll leading to the accumulation of a fluorescent product in the skin of the fruit. The chlorophyll breakdown product is stabilized by a propionate ester group. Banana-plant leaves also fluoresce in the same way. Green bananas do not fluoresce. The study suggested that this allows animals which can see light in the ultraviolet spectrum (tetrachromats and pentachromats) to more easily detect ripened bananas.[31]

Storage and transport

Bananas must be transported over long distances from the tropics to world markets. To obtain maximum shelf life, harvest comes before the fruit is mature. The fruit requires careful handling, rapid transport to ports, cooling, and refrigerated shipping. The goal is to prevent the bananas from producing their natural ripening agent, ethylene. This technology allows storage and transport for 3–4 weeks at 13 °C (55 °F). On arrival, bananas are held at about 17 °C (63 °F) and treated with a low concentration of ethylene. After a few days, the fruit begins to ripen and is distributed for final sale. Unripe bananas can not be held in home refrigerators because they suffer from the cold. Ripe bananas can be held for a few days at home. They can be stored indefinitely frozen, then eaten like an ice pop or cooked as a banana mush.

Recent studies have suggested that carbon dioxide (which bananas produce) and ethylene absorbents extend fruit life even at high temperatures.[32][33][34] This effect can be exploited by packing the fruit in a polyethylene bag and including an ethylene absorbent, e.g., potassium permanganate, on an inert carrier. The bag is then sealed with a band or string. This treatment has been shown to more than double lifespans up to 3–4 weeks without the need for refrigeration.

Trade

| Top 10 banana producing nations - 2009 (in million metric tons) | |

|---|---|

| ~26.2 | |

| 9.0 | |

| 8.2 | |

| 7.6 | |

| 7.2 | |

| 6.3 | |

| ~2.2 | |

| 2.1 | |

| 2.0 | |

| 1.5 | |

| World Total | 95.6 |

| Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations[3] ~ 2008 data | |

Bananas and plantains constitute a major staple food crop for millions of people in developing countries. In most tropical countries, green (unripe) bananas used for cooking represent the main cultivars. Bananas are cooked in ways that are similar to potatoes. Both can be fried, boiled, baked, or chipped and have similar taste and texture when served. One banana provides about the same calories as one potato.

In 2009, India led the world in banana production, representing approximately 28% of the worldwide crop, mostly for domestic consumption. The six leading exporting countries (Table, right) together accounted for about two-thirds of exports, each contributing more than 6 million tons, according to Food and Agriculture Organization statistics.

Most producers are small-scale farmers either for home consumption or local markets. Because bananas and plantains produce fruit year-round, they provide an extremely valuable food source during the hunger season (when the food from one annual/semi-annual harvest has been consumed, and the next is still to come). Bananas and plantains are therefore critical to global food security.

Bananas are among the most widely consumed foods in the world. Most banana farmers receive a low price for their produce as grocery companies pay discounted prices for buying in enormous quantity. Price competition among grocers has reduced their margins, leading to lower prices for growers. Chiquita, Del Monte, Dole, and Fyffes grow their own bananas in Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Honduras. Banana plantations are capital intensive and demand significant expertise. The majority of independent growers are large and wealthy landowners in these countries. Producers have attempted to raise prices via marketing them as "fair trade" or Rainforest Alliance-certified in some countries.

The banana has an extensive trade history beginning with the founding of the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) at the end of the 19th century. For much of the 20th century, bananas and coffee dominated the export economies of Central America. In the 1930s, bananas and coffee made up as much as 75% of the region's exports. As late as 1960, the two crops accounted for 67% of the exports from the region. Though the two were grown in similar regions, they tended not to be distributed together. The United Fruit Company based its business almost entirely on the banana trade, because the coffee trade proved too difficult to control. The term "banana republic" has been applied to most countries in Central America, but from a strict economic perspective only Costa Rica, Honduras, and Panama had economies dominated by the banana trade.

The European Union has traditionally imported many of their bananas from former European Caribbean colonies, paying guaranteed prices above global market rates. As of 2005, these arrangements were in the process of being withdrawn under pressure from other major trading powers, principally the United States. The withdrawal of these indirect subsidies to Caribbean producers is expected to favour the banana producers of Central America, in which American companies have an economic interest.

The United States produces few bananas. A mere 14,000 tonnes (14,000 long tons; 15,000 short tons) were grown in Hawaii in 2001.[35] Bananas were once grown in Florida and southern California.[36]

Pests, diseases, and natural disasters

While in no danger of outright extinction, the most common edible banana cultivar Cavendish (extremely popular in Europe and the Americas) could become unviable for large-scale cultivation in the next 10–20 years. Its predecessor 'Gros Michel', discovered in the 1820s, suffered this fate. Like almost all bananas, Cavendish lacks genetic diversity, which makes it vulnerable to diseases, threatening both commercial cultivation and small-scale subsistence farming.[37][38] Some commentators remarked that those variants which could replace what much of the world considers a "typical banana" are so different that most people would not consider them the same fruit, and blame the decline of the banana on monogenetic cultivation driven by short-term commercial motives.[29]

Panama Disease

Panama disease is caused by a fusarium soil fungus (Race 1), which enters the plants through the roots and travels with water into the trunk and leaves, producing gels and gums that cut off the flow of water and nutrients, causing the plant to wilt, and exposing the rest of the plant to lethal amounts of sunlight. Prior to 1960, almost all commercial banana production centered on 'Gros Michel', which was highly susceptible.[39] Cavendish was chosen as the replacement for Gros Michel because, among resistant cultivars, it produces the highest quality fruit. However, more care is required for shipping the Cavendish, and its quality compared to Gros Michel is debated.

According to current sources, a deadly form of Panama disease is infecting Cavendish. All plants are genetically identical, which prevents evolution of disease resistance. Researchers are examining hundreds of wild varieties for resistance.[39]

Tropical Race 4

TR4 is a reinvigorated strain of Panama disease first discovered in 1993. This virulent form of fusarium wilt has wiped out Cavendish in several southeast Asian countries. It has yet to reach the Americas; however, soil fungi can easily be carried on boots, clothing, or tools. This is how Tropical Race 4 travels and is its most likely route into Latin America. Cavendish is highly susceptible to TR4, and over time, Cavendish is almost certain to disappear from commercial production by this disease. Unfortunately, the only known defense to TR4 is genetic resistance.

Black Sigatoka

Black sigatoka is a fungal leaf spot disease first observed in Fiji in 1963 or 1964. Black Sigatoka (also known as black leaf streak) has spread to banana plantations throughout the tropics from infected banana leaves that were used as packing material. It affects all main cultivars of bananas and plantains, impeding photosynthesis by blackening parts of the leaves, eventually killing the entire leaf. Starved for energy, fruit production falls by 50% or more, and the bananas that do grow ripen prematurely, making them unsuitable for export. The fungus has shown ever-increasing resistance to treatment, with the current expense for treating 1 hectare (2.5 acres) exceeding $1,000 per year. In addition to the expense, there is the question of how long intensive spraying can be environmentally justified. Several resistant cultivars of banana have been developed, but none has yet received commercial acceptance due to taste and texture issues.

In East Africa

With the arrival of Black sigatoka, banana production in eastern Africa fell by over 40%. For example, during the 1970s, Uganda produced 15 to 20 tonnes (15 to 20 long tons; 17 to 22 short tons) of bananas per hectare. Today, production has fallen to only 6 tonnes (5.9 long tons; 6.6 short tons)per hectare.

The situation has started to improve as new disease-resistant cultivars have been developed by the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture and the National Agricultural Research Organisation of Uganda (NARO), such as FHIA-17 (known in Uganda as the Kabana 3). These new cultivars taste different from the Cabana banana, which has slowed their acceptance by local farmers. However, by adding mulch and manure to the soil around the base of the plant, these new cultivars have substantially increased yields in the areas where they have been tried.

The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture and NARO, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and CGIAR have started trials for genetically modified bananas that are resistant to both Black sigatoka and banana weevils. It is developing cultivars specifically for smallholder and subsistence farmers.

Banana Bunchy Top Virus (BBTV)

This virus jumps from plant to plant using aphids. It stunts leaves, resulting in a "bunched" appearance. Generally, an infected plant does not produce fruit, although mild strains exist which allow some production. These mild strains are often mistaken for malnourishment, or a disease other than BBTV. There is no cure; however, its effect can be minimized by planting only tissue-cultured plants (in vitro propagation), controlling aphids, and immediately removing and destroying infected plants.

Uses

Food and cooking

Fruit

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 371 kJ (89 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

22.84 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 12.23 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 2.6 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.33 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.09 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

One banana is 100–150 g. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[40] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[41] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bananas are the staple starch of many tropical populations. Depending upon cultivar and ripeness, the flesh can vary in taste from starchy to sweet, and texture from firm to mushy. Both skin and inner part can be eaten raw or cooked. Bananas' flavor is due, amongst other chemicals, to isoamyl acetate which is one of the main constituents of banana oil.

During the ripening process, bananas produce a plant hormone called ethylene, which indirectly affects the flavor. Among other things, ethylene stimulates the formation of amylase, an enzyme that breaks down starch into sugar, influencing the taste of bananas. The greener, less ripe bananas contain higher levels of starch and, consequently, have a "starchier" taste. On the other hand, yellow bananas taste sweeter due to higher sugar concentrations. Furthermore, ethylene signals the production of pectinase, an enzyme which breaks down the pectin between the cells of the banana, causing the banana to soften as it ripens.[42][43]

Bananas are eaten deep fried, baked in their skin in a split bamboo, or steamed in glutinous rice wrapped in a banana leaf. Bananas can be made into jam. Banana pancakes are popular amongst backpackers and other travelers in South Asia and Southeast Asia. This has elicited the expression Banana Pancake Trail for those places in Asia that cater to this group of travelers. Banana chips are a snack produced from sliced dehydrated or fried banana or plantain, which have a dark brown color and an intense banana taste. Dried bananas are also ground to make banana flour. Extracting juice is difficult, because when a banana is compressed, it simply turns to pulp. Bananas feature prominently in Philippine cuisine, being part of traditional dishes and desserts like maruya, turrón, and halo-halo. Most of these dishes use the Saba or Cardaba banana cultivar. Pisang goreng, bananas fried with batter similar to the Filipino maruya, is a popular dessert in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. A similar dish is known in the United States as banana fritters.

Plantains are used in various stews and curries or cooked, baked or mashed in much the same way as potatoes.

Seeded bananas (Musa balbisiana), one of the forerunners of the common domesticated banana,[44] are sold in markets in Indonesia.

Flower

Banana hearts are used as a vegetable[45] in South Asian and Southeast Asian cuisine, either raw or steamed with dips or cooked in soups and curries. The flavor resembles that of artichoke. As with artichokes, both the fleshy part of the bracts and the heart are edible.

Leaves

Banana leaves are large, flexible, and waterproof. They are often used as ecologically friendly disposable food containers or as "plates" in South Asia and several Southeast Asian countries. Especially in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu in every occasion the food must be served in a banana leaf and as a part of the food a banana is served. Steamed with dishes they impart a subtle sweet flavor. They often serve as a wrapping for grilling food. The leaves contain the juices, protect food from burning and add a subtle flavor.[46]

Trunk

The tender core of the banana plant's trunk is also used in South Asian and Southeast Asian cuisine, and notably in the Burmese dish mohinga.

Potential health effects

Along with other fruits and vegetables, consumption of bananas may be associated with a reduced risk of colorectal cancer[47] and in women, breast cancer[48] and renal cell carcinoma.[49]

Individuals with a latex allergy may experience a reaction to bananas.[50]

Bananas contain moderate amounts of vitamin B6, vitamin C, manganese and potassium,[51] possibly contributing to electrolyte balance.

In India, juice is extracted from the corm and used as a home remedy for jaundice, sometimes with the addition of honey, and for kidney stones.[52]

Fiber

Textiles

The banana plant has long been a source of fiber for high quality textiles. In Japan, banana cultivation for clothing and household use dates back to at least the 13th century. In the Japanese system, leaves and shoots are cut from the plant periodically to ensure softness. Harvested shoots are first boiled in lye to prepare fibers for yarn-making. These banana shoots produce fibers of varying degrees of softness, yielding yarns and textiles with differing qualities for specific uses. For example, the outermost fibers of the shoots are the coarsest, and are suitable for tablecloths, while the softest innermost fibers are desirable for kimono and kamishimo. This traditional Japanese cloth-making process requires many steps, all performed by hand.[53]

In a Nepalese system the trunk is harvested instead, and small pieces are subjected to a softening process, mechanical fiber extraction, bleaching and drying. After that, the fibers are sent to the Kathmandu Valley for use in rugs with a silk-like texture. These banana fiber rugs are woven by traditional Nepalese hand-knotting methods, and are sold RugMark certified.

In South Indian state of Tamil Nadu after harvesting for fruit the trunk (outer layer of the shoot) is made into fine thread used in making of flower garlands instead of thread.

Paper

Banana fiber is used in the production of banana paper. Banana paper is used in two different senses: to refer to a paper made from the bark of the banana plant, mainly used for artistic purposes, or paper made from banana fiber, obtained with an industrialized process from the stem and the non-usable fruits. The paper itself can be either hand-made or in industrial processes.

Cultural roles

Arts

- The song "Yes! We Have No Bananas" was written by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn and originally released in 1923; for many decades, it was the best-selling sheet music in history. Since then the song has been rerecorded several times and has been particularly popular during banana shortages.

- A person slipping on a banana peel has been a staple of physical comedy for generations. A 1910 comedy recording features a popular character of the time, "Uncle Josh", claiming to describe his own such incident:[54]

Now I don't think much of the man that throws a banana peelin' on the sidewalk, and I don't think much of the banana peel that throws a man on the sidewalk neither ... my foot hit the bananer peelin' and I went up in the air, and I come down ker-plunk, jist as I was pickin' myself up a little boy come runnin' across the street ... he says, "Oh mister, won't you please do that agin? My little brother didn't see you do it."

- The poet Bashō is named after the Japanese word for a banana plant. The "bashō" planted in his garden by a grateful student became a source of inspiration to his poetry, as well as a symbol of his life and home.[55]

- The Japanese novelist Mihoko Yoshimoto changed her name to Banana Yoshimoto because she liked banana flowers.

Symbols

Bananas are also humorously used as a phallic symbol due to similarities in size and shape. This is typified by the artwork of the debut album of The Velvet Underground, which features a banana on the front cover, yet on the original LP version, the design allowed the listener to 'peel' this banana to find a pink phallus on the inside.

Religion

In Burma, bunches of green bananas surrounding a green coconut in a tray form an important part of traditional offerings to the Buddha and the Nats.

In all the important festivals and occasions of Tamils the serving of bananas plays a prominent part. The banana (Tamil:வாழை or வாழைப்பழம்) is one of three fruits with this significance, the others being mango and jack fruit.

East Africa

Most farms supply local consumption. Cooking bananas represent a major food source and a major income source for smallhold farmers. In East African highlands bananas are of greatest importance as a staple food crop. In countries such as Uganda, Burundi, and Rwanda per capita consumption has been estimated at Template:Kg to lb per year, the highest in the world.

Other uses

Banana sap is extremely sticky and can be used as a practical adhesive.[citation needed] Sap can be obtained from the pseudostem, from the peelings, or from the flesh.

In regions where bananas are grown, the large leaves are sometimes used as umbrellas. The pseudostems, being floatable, can be tied together to form a floatation device.[46]

Banana sap leaves indelible dark stains on clothes.

A banana equivalent dose is used in the nuclear industry to compare radiation doses received from radioactive materials to the dose received from the radioactivity in bananas.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b "Tracing antiquity of banana cultivation in Papua New Guinea". The Australia & Pacific Science Foundation. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ www.traditionaltree.org, Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry, Musa species (banana and plantain) agroforestry.net

- ^ a b "FAOSTAT: ProdSTAT: Crops". Food and Agriculture Organization. 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- ^ Yes, we have more bananas published in the Royal Horticultural Society Journals, May 2002

- ^ "Banana from ''Fruits of Warm Climates'' by Julia Morton". Hort.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ See Greenearth, Inc., Banana Plant Growing Info. Retrieved 2008.12.20.

- ^ Angolo, A (2008-05-15). "Banana plant with five hearts is instant hit in Negros Occ". ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|storyid=ignored (help) - ^ James P. Smith, Vascular Plant Families. Mad River Press, 1977.

- ^ CRC Handbook on Radiation Measurement and Protection, Vol 1 pg. 620 Table A.3.7.12, CRC Press, 1978

- ^ [1] Stephen Cass, Corinna Wu (2007). Everything Emits Radiation—Even You: The millirems pour in from bananas, bomb tests, the air, bedmates... Discover: Science, Technology, and the Future, published online June 4, 2007

- ^ http://enochthered.wordpress.com/category/banana-dose/

- ^ Liberty Hyde Bailey, The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture. 1916. p. 2076

- ^ a b Dan Keppel, Banana, Hudson Street Press, 2008; p. 44.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 5 Aug 2010.

- ^ Bailey, pp. 2076–2079.

- ^ a b Banana cultivar names and synonyms in Southeast Asia by Ramón V. Valmayor at Google Books

- ^ a b c "Musa paradisiaca". http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Michel H. Porcher; Prof. Snow Barlow (19/07/2002). "Sorting Musa names". The University of Melbourne, [2]. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ "Musa sapientum". http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b Watson, p. 54

- ^ Evidence for banana cultivation and animal husbandry during the first millennium BC in the forest of southern Cameroon. Mbida VM, Van Neer W, Doutrelepont H, Vrydaghs L. (2000) JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SCIENCE 27:151-162

- ^ Friedrich J. Zeller (2005). "Herkunft, Diversität und Züchtung der Banane und kultivierter Zitrusarten (Origin, diversity and breeding of banana and plantain (Musa spp.))" (PDF). Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics.

- ^ "Africa's earliest bananas?" (PDF). Journal of Archeological Science. 2005-06-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ Randrianja, Solofo abd Stephen Ellis: Madagascar: A Short History. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- ^ "Bananas and plantains". Botgard.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary: banana". Retrieved 02-11-2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Peed, Mike: "We Have No Bananas: Can Scientists Defeat a Devastating Blight?" The New Yorker, January 10, 2011, pp. 28-34. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- ^ a b "Phora Ltd. - History of Banana". Phora-sotoby.com. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ a b Big-business greed killing the banana - Independent, via The New Zealand Herald, Saturday 24 May 2008, Page A19

- ^ a b c d Castle, Matt (August 24, 2009). "The Unfortunate Sex Life of the Banana". DamnInteresting.com.

- ^ Moser, Simone (2008). "Blue luminescence of ripening bananas". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 47 (46): 8954–8957. doi:10.1002/anie.200803189. PMC 2912500. PMID 18850621.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Scott, KJ, McGlasson WB and Roberts EA (1970) Potassium Permanganate as an Ethylene Absorbent in Polyethylene Bags to Delay the Ripening of Bananas During Storage. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture and Animal Husbandry 110, 237–240.

- ^ Scott KJ, Blake, JR, Stracha n, G Tugwell, BL and McGlasson WB (1971) Transport of Bananas at Ambient Temperatures using Polyethylene Bags. Tropical cha Agriculture (Trinidad ) 48, 163–165.

- ^ Scott, KJ and Gandanegara, S (1974) Effect of Temperature on the Storage Life of bananas Held in Polyethylene Bags with an Ethylene Absorbent. Tropical Agriculture (Trinidad ) 51,23–26.

- ^ "Crop Profile for Bananas in Hawaii". Ipmcenters.org. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc., Banana Fruit Facts. Retrieved 2008.12.30.

- ^ "A future with no bananas?". New Scientist. 2006-05-13. Retrieved 09-12-2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Montpellier, Emile Frison (2003-02-08). "Rescuing the banana". New Scientist. Retrieved 09-12-2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Barker, C. L. Conservation: Peeling away. National Geographic Magazine, November 2008.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ "Fruit Ripening". Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ "Ethylene Process". Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Plant Breeding Abstracts, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, 1949, p.162

- ^ Solomon, C (1998). Encyclopedia of Asian Food (Periplus ed.). Australia: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 0855616881. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ a b "Banana". Hortpurdue.edu. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ Deneo-Pellegrini, H (1996). "Vegetables, fruits, and risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study from Uruguay". Nutrition & Cancer. 25 (3): 297–304. doi:10.1080/01635589609514453. PMID 8771572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zhang, CX (2009). "Greater vegetable and fruit intake is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer among Chinese women". International Journal of Cancer. 125 (1): 181–8. doi:10.1002/ijc.24358. PMID 19358284.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rashidkhani, B (2005). "Fruits, vegetables and risk of renal cell carcinoma: a prospective study of Swedish women". International Journal of Cancer. 113 (3): 451–5. doi:10.1002/ijc.20577. PMID 15455348.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Taylor, JS (2004). "Latex allergy: diagnosis and management". Dermatological Therapy. 17 (4): 289–301. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04024.x. PMID 15327474.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nutrition Facts for raw banana, one NLEA serving, 126 g".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help) - ^ Healing Power of Foods: Nature's Prescription of Common Diseases, Pustak Mahal, 2004, ISBN 81-223-0748-5, p.49

- ^ "Traditional Crafts of Japan - Kijoka Banana Fiber Cloth". Association for the Promotion of Traditional Craft Industries. Retrieved 11-12-2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Stewart, Cal. "Collected Works of Cal Stewart part 2". Uncle Josh in a Department Store (1910). The Internet Archive. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ Matsuo Basho: the Master Haiku Poet, Kodansha Europe, ISBN 0-87011-553-7

References

- Denham, T., Haberle, S. G., Lentfer, C., Fullagar, R., Field, J., Porch, N., Therin, M., Winsborough B., and Golson, J. Multi-disciplinary Evidence for the Origins of Agriculture from 6950-6440 Cal BP at Kuk Swamp in the Highlands of New Guinea. Science, June 2003 issue.

- Editors (2006). "Banana fiber rugs". Dwell. 6 (7): 44.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help) Brief mention of banana fiber rugs - Leibling, Robert W. and Pepperdine, Donna (2006). "Natural remedies of Arabia". Saudi Aramco World. 57 (5): 14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Banana etymology, banana flour. - Skidmore, T., Smith, P. - Modern Latin America (5th edition), (2001) New York: Oxford University Press

- Watson, Andrew. Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Further reading

- Dan Koeppel, Banana: The Fate of the Fruit that Changed the World, ISBN 978-1-59463-038-5, [3]

- Dan Koeppel, The New York Times article of June 18, 2008, Yes, We Will Have No Bananas

- Harriet Lamb, "Fighting The Banana Wars and other Fairtrade Battles", ISBN 978-1-84604-083-2

External links

select an article title from: Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA