Henipavirus

| Henipaviruses | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group V ((−)ssRNA)

|

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Henipavirus

|

| Type species | |

| Hendravirus | |

| Species | |

Henipavirus is a genus of the family Paramyxoviridae, order Mononegavirales containing two members, Hendravirus and Nipahvirus. The henipaviruses are naturally harboured by Pteropid fruit bats (flying foxes) and are characterised by a large genome, a wide host range and their recent emergence as zoonotic pathogens capable of causing illness and death in domestic animals and humans.[1]

In April 27, 1999, 257 cases of febrile encephalitis were reported to the Malaysian Ministry of Health (MOH), including 100 deaths. Laboratory results from 65 patients who died suggested recent Nipah virus infection.[2].A highly fatal (case-fatality ratio 38%–75%), febrile human encephalitis in Malaysia and Singapore in 1999 and in Bangladesh during the winters of 2001, 2003, and 2004 has been detected which was caused by Nipah virus.[3]. From February 2011, Nipah outbreak occurred at Hatibandha Upazila under Lalmonirhat district which is in northern part of Bangladesh. Till to date (7th February, 2011) there are 24 cases and 17 deaths.[4]

Virus structure

Henipaviruses are pleomorphic (variably shaped), ranging in size from 40 to 600 nm in diameter.[5] They possess a lipid membrane overlying a shell of viral matrix protein. At the core is a single helical strand of genomic RNA tightly bound to N (nucleocapsid) protein and associated with the L (large) and P (phosphoprotein) proteins which provide RNA polymerase activity during replication.

Embedded within the lipid membrane are spikes of F (fusion) protein trimers and G (attachment) protein tetramers. The function of the G protein is to attach the virus to the surface of a host cell via EFNB2, a highly conserved protein present in many mammals.[6][7] The F protein fuses the viral membrane with the host cell membrane, releasing the virion contents into the cell. It also causes infected cells to fuse with neighbouring cells to form large, multinucleated syncytia.

Genome structure

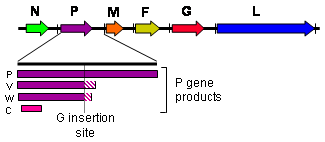

As with all viruses in the Mononegavirales order, the Hendra virus and Nipah virus genomes are non-segmented, single-stranded negative-sense RNA. Both genomes are 18.2 kb in size and contain six genes corresponding to six structural proteins.[8]

In common with other members of the Paramyxovirinae subfamily, the number of nucleotides in the henipavirus genome is a multiple of six, known as the 'rule of six'. Deviation from the rule of six, through mutation or incomplete genome synthesis, leads to inefficient viral replication, probably due to structural constraints imposed by the binding between the RNA and the N protein.

Henipaviruses employ an unusual process called RNA editing to generate multiple proteins from a single gene. The process involves the insertion of extra guanosine residues into the P gene mRNA prior to translation. The number of residues added determines whether the P, V or W proteins are synthesised. The functions of the V and W proteins are unknown, but they may be involved in disrupting host antiviral mechanisms.

Hendra virus

Emergence

Hendra virus (originally Equine morbillivirus) was discovered in September 1994 when it caused the deaths of fourteen horses, and a trainer at a training complex in Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane in Queensland, Australia.[9]

The index case, a mare, was housed with 23 other horses after falling ill and died two days later. Subsequently, 19 of the remaining horses succumbed with 13 dying. Both the trainer and a stable hand were involved in nursing the index case and both fell ill within one week of the horse’s death with an influenza-like illness. The stable hand recovered while the trainer died of respiratory and renal failure. The source of virus was most likely frothy nasal discharge from the index case.

A second outbreak occurred in August 1994 (chronologically preceding the first outbreak) in Mackay 1000 km north of Brisbane resulting in the deaths of two horses and their owner.[10] The owner assisted in necropsies of the horses and within three weeks was admitted to hospital suffering from meningitis. He recovered, but 14 months later developed neurologic signs and died. This outbreak was diagnosed retrospectively by the presence of Hendra virus in the brain of the patient.

A survey of wildlife in the outbreak areas was conducted and identified pteropid fruit bats as the most likely source of Hendra virus with a seroprevalence of 47%. All of the other 46 species sampled were negative. Virus isolations from the reproductive tract and urine of wild bats indicated that transmission to horses may have occurred via exposure to bat urine or birthing fluids.[11]

Outbreaks

A total of thirteen outbreaks of Hendra virus have occurred since 1994, all involving infection of horses. Four of these outbreaks have spread to humans as a result of direct contact with infected horses.

- August 1994, Mackay, Queensland: Death of two horses and one person.[10]

- September 1994, Brisbane, Queensland: 14 horses died from a total of 20 infected. Two people infected with one death.[9]

- January 1999, Cairns, Queensland: Death of one horse.[12]

- October 2004, Cairns, Queensland: Death of one horse. A vet involved in autopsy of the horse was infected with Hendra virus and suffered a mild illness.[13]

- December 2004, Townsville, Queensland: Death of one horse.[13]

- June 2006, Sunshine Coast, Queensland: Death of one horse.[13]

- October 2006, Murwillumbah, New South Wales: Death of one horse.[14]

- July 2007, Clifton Beach, Queensland: Infection of one horse (euthanized).[15]

- July 2008, Redlands, Brisbane, Queensland: Death of five horses; four died from the Henda virus, the remaining animal recovered but was euthanized because of the threat to health. Two veterinary workers from the affected property were infected leading to the death of one, veterinary surgeon Dr. Ben Cuneen, on the 20th of August, 2008. The second veterinarian was hospitalized after pricking herself with a needle she had used to euthanize the horse that had recovered. A nurse exposed to the disease while assisting Cuneen in caring for the infected horses was also hospitalized.[16]

- July 2008, Cannonvale, Queensland: Death of two horses.

- August 2009, Cawarral, Queensland: Death of one horse; the death of three other horses is being investigated. Queensland veterinary surgeon Alister Rodgers tested positive after treating the horses.[17] On September 1, 2009 after two weeks in a coma, he became the fourth person to die from exposure to the virus.[18]

- May 2010, Tewantin, Queensland: Death of one horse.[19]

The distribution of black and spectacled flying foxes covers the outbreak sites, and the timing of incidents indicates a seasonal pattern of outbreaks possibly related to the seasonality of fruit bat birthing. As there is no evidence of transmission to humans directly from bats, it is thought that human infection only occurs via an intermediate host.

Pathology

Flying foxes are unaffected by Hendra virus infection. Symptoms of Hendra virus infection of humans may be respiratory, including hemorrhage and edema of the lungs, or encephalitic resulting in meningitis. In horses, infection usually causes pulmonary edema and congestion.

Nipah virus

Emergence

Nipah virus was identified in 1999 when it caused an outbreak of neurological and respiratory disease on pig farms in peninsular Malaysia, resulting in 105 human deaths and the culling of one million pigs.[10] In Singapore, 11 cases including one death occurred in abattoir workers exposed to pigs imported from the affected Malaysian farms. The Nipah virus has been classified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a Category C agent.[20] The name "Nipah" is taken after the place, Kampung Nipah in Negeri Sembilan where the virus was first isolated from humans in that area.[21]

The outbreak was originally mistaken for Japanese encephalitis (JE), however, physicians in the area noted that persons who had been vaccinated against JE were not protected, and the number of cases among adults was unusual [22] Despite the fact that these observations were recorded in the first month of the outbreak, the Ministry of Health failed to react accordingly and instead launched a nationwide campaign to educate people on the dangers of JE and its vector, Culex mosquitoes.

Symptoms of infection from the Malaysian outbreak were primarily encephalitic in humans and respiratory in pigs. Later outbreaks have caused respiratory illness in humans, increasing the likelihood of human-to-human transmission and indicating the existence of more dangerous strains of the virus.

Based on seroprevalence data and virus isolations, the primary reservoir for Nipah virus was identified as Pteropid fruit bats including Pteropus vampyrus (Large Flying Fox) and Pteropus hypomelanus (Small Flying-fox), both of which occur in Malaysia.

The transmission of Nipah virus from flying foxes to pigs is thought to be due to an increasing overlap between bat habitats and piggeries in peninsular Malaysia. At the index farm, fruit orchards were in close proximity to the piggery, allowing the spillage of urine, faeces and partially eaten fruit onto the pigs.[23] Retrospective studies demonstrate that viral spillover into pigs may have been occurring in Malaysia since 1996 without detection.[10] During 1998, viral spread was aided by the transfer of infected pigs to other farms where new outbreaks occurred.

Outbreaks

Eight more outbreaks of Nipah virus have occurred since 1998, all within Bangladesh and neighbouring parts of India. The outbreak sites lie within the range of Pteropus species (Pteropus giganteus). As with Hendra virus, the timing of the outbreaks indicates a seasonal effect.

- 2001 January 31 – February 23, Siliguri, India: 66 cases with a 74% mortality rate.[24] 75% of patients were either hospital staff or had visited one of the other patients in hospital, indicating person-to-person transmission.

- 2001 April – May, Meherpur district, Bangladesh: 13 cases with nine fatalities (69% mortality).[25]

- 2003 January, Naogaon district, Bangladesh: 12 cases with eight fatalities (67% mortality).[25]

- 2004 January – February, Manikganj and Rajbari provinces, Bangladesh: 42 cases with 14 fatalities (33% mortality).

- 2004 19 February – 16 April, Faridpur district, Bangladesh: 36 cases with 27 fatalities (75% mortality). Epidemiological evidence strongly suggests that this outbreak involved person-to-person transmission of Nipah virus, which had not previously been confirmed.[26] 92% of cases involved close contact with at least one other person infected with Nipah virus. Two cases involved a single short exposure to an ill patient, including a rickshaw driver who transported a patient to hospital. In addition, at least six cases involved acute respiratory distress syndrome which has not been reported previously for Nipah virus illness in humans. This symptom is likely to have assisted human-to-human transmission through large droplet dispersal.

- 2005 January, Tangail district, Bangladesh: 12 cases with 11 fatalities (92% mortality). The virus was probably contracted from drinking date palm juice contaminated by fruit bat droppings or saliva.[27]

- 2007 February – May, Nadia District, India: up to 50 suspected cases with 3-5 fatalities. The outbreak site borders the Bangladesh district of Kushtia where eight cases of Nipah virus encephalitis with five fatalities occurred during March and April 2007. This was preceded by an outbreak in Thakurgaon during January and February affecting seven people with three deaths.[28] All three outbreaks showed evidence of person-to-person transmission.

- 2008 February - March, Manikganj and Rajbari provinces, Bangladesh: Nine cases with eight fatalities.[29]

- 2011 February- till: The outbreak of Nipah Virus is occurred at Hatibanda, Lalmonirhat, Bangladesh on the onset of 2011. There have a record of 21 school childrens death due to infection of Nipah virus on 4th February, 2011. IEDCR has confirmed the infection is due to this virus [30]. Local schools are declared for one week leave to prevent the spread. However, people are also requested to avoid consumption of fruits or fruit products (e.g. raw date palm juice) contaminated with urine or saliva from infected fruit bats was the most likely source of infection.[31]

Eleven isolated cases of Nipah virus encephalitis have also been documented in Bangladesh since 2001.

Nipah virus has been isolated from Lyle's flying fox (Pteropus lylei) in Cambodia[32] and viral RNA found in urine and saliva from P. lylei and Horsfield's roundleaf bat (Hipposideros larvatus) in Thailand.[33] Infective virus has also been isolated from environmental samples of bat urine and partially-eaten fruit in Malaysia.[34] Antibodies to henipaviruses have also been found in fruit bats in Madagascar (Pteropus rufus, Eidolon dupreanum)[35] and Ghana (Eidolon helvum)[36] indicating a wide geographic distribution of the viruses. No infection of humans or other species have been observed in Cambodia, Thailand or Africa.

Pathology

In humans, the infection presents as fever, headache and drowsiness. Cough, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weakness, problems with swallowing and blurred vision are relatively common. About a quarter of the patients have seizures and about 60% become comatose and might need mechanical ventilation. In patients with severe disease, their conscious state may deteriorate and they may develop severe hypertension, fast heart rate, and very high temperature.

Nipah virus is also known to cause relapse encephalitis. In the initial Malaysian outbreak, a patient presented with relapse encephalitis some 53 months after his initial infection. There is no definitive treatment for Nipah encephalitis, apart from supportive measures, such as mechanical ventilation and prevention of secondary infection. Ribavirin, an antiviral drug, was tested in the Malaysian outbreak and the results were encouraging, though further studies are still needed.

In animals, especially in pigs, the virus causes porcine respiratory and neurologic syndrome also known as barking pig syndrome or one mile cough.

Causes of emergence

The emergence of henipaviruses parallels the emergence of other zoonotic viruses in recent decades. SARS coronavirus, Australian bat lyssavirus, Menangle virus and probably Ebola virus and Marburg virus are also harbored by bats and are capable of infecting a variety of other species. The emergence of each of these viruses has been linked to an increase in contact between bats and humans, sometimes involving an intermediate domestic animal host. The increased contact is driven both by human encroachment into the bats’ territory (in the case of Nipah, specifically pigpens in said territory) and by movement of bats towards human populations due to changes in food distribution and loss of habitat.

There is evidence of habitat loss for flying foxes both in South Asia and Australia (particularly along the east coast) as well as encroachment of human dwellings and agriculture into the remaining habitats, creating greater overlap of human and flying fox distributions.

See also

References

- ^ Sawatsky; et al. (2008). "Hendra and Nipah Virus". Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00057012.htm

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol12no02/05-1247.htm#1

- ^ http://www.iedcr.org/

- ^ Hyatt AD, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Wise TG, Hengstberger SG (2001). "Ultrastructure of Hendra virus and Nipah virus within cultured cells and host animals". Microbes Infect. 3 (4): 297–306. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01383-1. PMID 11334747.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bonaparte, M; Dimitrov, A; Bossart, K; et al. (2005). "Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus". PNAS. 102 (30): 10652–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504887102. PMC 1169237. PMID 15998730.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Negrete OA, Levroney EL, Aguilar HC; et al. (2005). "EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus". Nature. 436 (7049): 401–5. doi:10.1038/nature03838. PMID 16007075.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang L, Harcourt BH, Yu M; et al. (2001). "Molecular biology of Hendra and Nipah viruses". Microbes Infect. 3 (4): 279–87. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01381-8. PMID 11334745.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Selvey LA, Wells RM, McCormack JG; et al. (1995). "Infection of humans and horses by a newly described morbillivirus". Med. J. Aust. 162 (12): 642–5. PMID 7603375.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Field H, Young P, Yob JM, Mills J, Hall L, Mackenzie J (2001). "The natural history of Hendra and Nipah viruses". Microbes Infect. 3 (4): 307–14. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01384-3. PMID 11334748.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Halpin K, Young PL, Field HE, Mackenzie JS (2000). "Isolation of Hendra virus from pteropid bats: a natural reservoir of Hendra virus". J. Gen. Virol. 81 (Pt 8): 1927–32. PMID 10900029.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Field HE, Barratt PC, Hughes RJ, Shield J, Sullivan ND (2000). "A fatal case of Hendra virus infection in a horse in north Queensland: clinical and epidemiological features". Aust. Vet. J. 78 (4): 279–80. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb11758.x. PMID 10840578.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Hanna JN, McBride WJ, Brookes DL; et al. (2006). "Hendra virus infection in a veterinarian". Med. J. Aust. 185 (10): 562–4. PMID 17115969.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ .NSW Department of Primary Industries. Animal Health Surveillance 2006; 4:4–5.

- ^ ProMED-mail. Hendra virus, human, equine – Australia (Queensland) (03): correction. ProMED-mail 2007; 3 September: 20070903.2896.

- ^ Brown, Kimberly S. "Horses and Human Die in Australia Hendra Outbreak; Government Comes Under Fire." The Horse, online edition. Accessed August 26, 2008

- ^ "Vet tests positive to Hendra virus" The Australian. Accessed August 20, 2009

- ^ "Alister Rodgers dies of Hendra virus after 2 weeks in coma" The Australian. Accessed September 2, 2009

- ^ "Horse dies from Hendra virus in Queensland" news.com.au. Accessed May 20, 2010

- ^ bt.cdc.gov

- ^ Emerging Diseases: NIPAH VIRUS IN PIGS, Veterinary Research Institute, Department of Veterinary Services, Ministry of Agriculture Malaysia.

- ^ Dobbs and the viral encephalitis outbreak. Archived thread from the Malaysian "Doctors Only BBS".

- ^ Chua KB, Chua BH, Wang CW (2002). "Anthropogenic deforestation, El Niño and the emergence of Nipah virus in Malaysia". Malays J Pathol. 24 (1): 15–21. PMID 16329551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L; et al. (2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (2): 235–40. PMID 16494748.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD; et al. (2004). "Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh". Emerging Infect. Dis. 10 (12): 2082–7. PMID 15663842.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ICDDR,B (2004). "Nipah encephalitis outbreak over wide area of Western Bangladesh". Health and Science Bulletin. 2 (1): 7–11.

- ^ ICDDR,B (2005). "Nipah virus outbreak from date palm juice". Health and Science Bulletin. 3 (4): 1–5.

- ^ ICDDR,B (2007). "Person-to-person transmission of Nipah infection in Bangladesh". Health and Science Bulletin. 5 (4): 1–6.

- ^ ICDDR,B (2008). "Outbreaks of Nipah virus in Rajbari and Manikgonj". Health and Science Bulletin. 6 (1): 12–3.

- ^ http://www.thedailystar.net/newDesign/latest_news.php?nid=28294

- ^ http://www.prothom-alo.com/detail/date/2011-02-04/news/128856

- ^ Reynes JM, Counor D, Ong S; et al. (2005). "Nipah virus in Lyle's flying foxes, Cambodia". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (7): 1042–7. PMID 16022778.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wacharapluesadee S, Lumlertdacha B, Boongird K; et al. (2005). "Bat Nipah virus, Thailand". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (12): 1949–51. PMID 16485487.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chua KB, Koh CL, Hooi PS; et al. (2002). "Isolation of Nipah virus from Malaysian Island flying-foxes". Microbes Infect. 4 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01522-2. PMID 11880045.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lehlé C, Razafitrimo G, Razainirina J; et al. (2007). "Henipavirus and Tioman virus antibodies in pteropodid bats, Madagascar". Emerging Infect. Dis. 13 (1): 159–61. doi:10.3201/eid1301.060791. PMC 2725826. PMID 17370536.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayman D, Suu-Ire R, Breed A; et al. (2008). "Evidence of henipavirus infection in West African fruit bats". PLoS ONE. 3 (7): 2739. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002739. PMC 2453319. PMID 18648649.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

External links

- ViralZone: Henipavirus

- Hendra virus CSIRO FAQ

- Nipah virus CSIRO FAQ

- Henipavirus Henipavirus Ecology Research Group (HERG) INFO

- Animal viruses

- Queensland vet dies from Hendra virus—accessed 21Aug08

- Treatment : Virus's Achilles' Heel Revealed - Science, Feb 2009

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Paramyxoviridae