Ural-Altaic languages

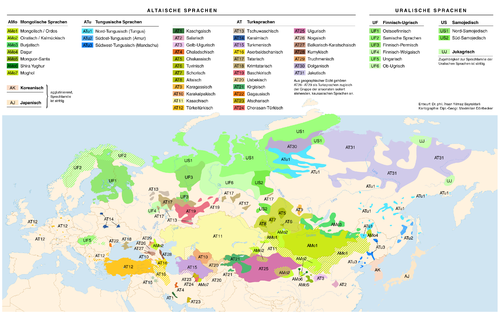

Ural–Altaic or Uralo-Altaic is a language-family proposal uniting the Uralic and Altaic languages.

Originally suggested in the 19th century, the hypothesis enjoyed wide acceptance among linguists into the mid 20th century. Since the 1960s, it has been controversial and rejected. From the 1990s, interest in a relationship between the Uralic and Altaic and Indo-European families has been revived in the context of the Eurasiatic hypothesis. Bomhard (2008) treats Uralic, Altaic and Indo-European as Eurasiatic daughter groups on equal footing.[1]

History of the hypothesis

Philip Johan von Strahlenberg, Swedish explorer and war prisoner in Siberia, described Finno-Ugric, Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Caucasian languages as sharing common features by 1730.

Rask described what he vaguely called "Scythian" languages in 1834, which included Finno-Ugric, Turkic, Samoyedic, Eskimo, Caucasian, Basque and others.

The hypothesis was elaborated at least as early as 1836 by W. Schott[2] and in 1838 by F. J. Wiedemann.[3]

The Altaic hypothesis, as mentioned by Finnish linguist and explorer Matthias Castrén[4][5] by 1844, included Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic, collectively known as "Chudic", and Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic, collectively known as "Tataric".

Subsequently, Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic were grouped together, on account of their especially similar features, while Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic were grouped as Uralic. Two contrasting language families were thereby formed, but the similarities between them led to their retention in a common grouping, named Ural–Altaic.

The Ural–Altaic family was widely accepted by linguists who studied Uralic and Altaic until well into the 20th century. In his article The Uralo-Altaic Theory in the Light of the Soviet Linguistics (1940), Nicholas Poppe attempted to refute Castren's views by concluding that the common agglutinating features may have arisen independently.[6] Beginning in the 1960s, the hypothesis came to be seen as controversial, largely due to the Altaic family itself not being universally accepted. Today, the hypothesis that Uralic and Altaic are related more closely to one another than to any other family has almost no adherents (Starostin et al. 2003:8). There are, however, a number of hypotheses that propose a macrofamily consisting of Uralic, Altaic and other families. None of these hypotheses has widespread support.

In his Altaic Etymological Dictionary, co-authored with Anna V. Dybo and Oleg A. Mudrak, Sergei Starostin characterized the Ural–Altaic hypothesis as "an idea now completely discarded" (2003:8). In Starostin's sketch of a "Borean" super-phylum, he puts Uralic and Altaic as daughters of an ancestral language of ca. 9,000 years ago from which the Dravidian languages and the Paleo-Siberian languages, including Eskimo-Aleut, are also descended. He posits that this ancestral language, together with Indo-European and Kartvelian, descends from a "Eurasiatic" protolanguage some 12,000 years ago, which in turn would be descended from a "Borean" protolanguage via Nostratic.[7]

Angela Marcantonio (2002) argues that the Finno-Permic and Ugric languages are no more closely related to each other than either is to Turkic, thereby positing a grouping very similar to Ural–Altaic or indeed to Castrén's original Altaic proposal.[8]

Relationship between Uralic and Altaic

The Altaic language family was generally accepted by linguists from the late 19th century up to the 1960s. For simplicity's sake, the following discussion assumes the validity of the Altaic language family, although for linguists who do not accept Altaic a relation of Altaic to Uralic is obviously a non-starter, though some part of "Altaic" (e.g. Turkic) might be related to Uralic, in theory.

It is important to distinguish two senses in which Uralic and Altaic might be related.

- Do Uralic and Altaic have a demonstrable genetic relationship?

- If they do have a demonstrable genetic relationship, do they form a valid linguistic taxon? For example, Germanic and Iranian have a genetic relationship via Proto-Indo-European, but they do not form a valid taxon within the Indo-European language family, whereas in contrast Iranian and Indic do via Indo-Iranian, a daughter language of Proto-Indo-European that subsequently calved into Indic and Iranian. In other words, showing genetic relationship does not suffice to establish a language family, such as the proposed Ural–Altaic family; it is also necessary to consider the family tree of the languages concerned to determine which language goes where.

This distinction is often overlooked but is fundamental to the genetic classification of languages (Greenberg 2005).

Evidence for a genetic relationship

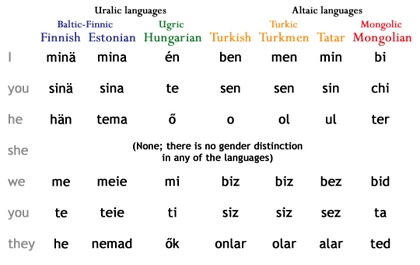

Some[who?] linguists point out strong similarities in the pronouns of Uralic and Altaic languages. Since pronouns are among the elements of language most resistant to change and it is very rare if not unheard-of for one language to replace its pronouns wholesale with those of another, these similarities, if accepted as real, would be strong evidence for genetic relationship. It should be noted that the "s" in the Finnic second person pronoun "sinä" is a result of the ti→si sound law,[9] and comes from earlier form *tinä, as in the plural form "te" and the Hungarian pronoun "te".

Other observations are that both Uralic and Altaic languages have vowel harmony, are agglutinating in structure (stringing suffixes, prefixes or both onto roots), use SOV word order, and lack grammatical gender. However, typological similarities such as these do not constitute evidence of genetic relationship on their own, as they may be the result of regional influence or coincidence. Thus other linguists argue that these typological similarities do not demonstrate a genetic relationship between Uralic and Altaic, ascribing these similarities instead to coincidence or mutual influence resulting in convergence.[citation needed]

Vocabulary of common origin

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2008) |

To demonstrate the existence of a language family, it is necessary to find cognate words that trace back to a common proto-language. Shared vocabulary alone does not show a relationship, as it may be loaned from one language to another or through the language of a third party.

There are shared words between, for example, Turkic and Ugric languages, because borrowing has occurred. However, it has been difficult to find proto-Ural–Altaic words across both language families. Such words would be found in all branches of the Uralic and Altaic trees and should follow regular sound changes from the proto-language to known modern languages. In addition, regular sound changes from Proto-Ural–Altaic to give Proto-Uralic and Proto-Altaic words should be found to demonstrate the existence of a Ural–Altaic vocabulary. So far, none of such words have been unambiguously demonstrated. In contrast, about 200 Uralic words are known and universally accepted.

Evidence for a Ural–Altaic taxon

The vowel-harmony argument has sometimes been used to justify the necessity of a Ural–Altaic family, but vowel harmony is found in other nearby languages as well, including Chukchi and Nivkh, as well as in various languages of Africa and the Americas. Furthermore, vowel harmony is a typological feature, and, according to the predominant opinion among linguists, typological features do not provide evidence for genetic relationship.

Some linguists maintain that Uralic and Altaic are related through a larger family, such as Eurasiatic or Nostratic, within which Uralic and Altaic are no more closely related to each other than either is to any other member of the proposed family, for instance than Uralic or Altaic is to Indo-European (e.g. Greenberg 2000:17).

See also

- Altaic languages

- Indo-Uralic languages

- Nostratic languages

- Proto-Uralic language

- Uralic languages

- Uralic–Yukaghir languages

- Uralo-Siberian languages

- Xiongnu

References

- ^ Bomhard, Allan R. (2008). Reconstructing Proto-Nostratic: Comparative Phonology, Morphology, and Vocabulary, 2 volumes. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16853-4

- ^ W. Schott, Versuch über die tatarischen Sprachen (1836)

- ^ F. J. Wiedemann, Ueber die früheren Sitze der tschudischen Völker und ihre Sprachverwandschaft mit dem Völkern Mittelhochasiens (1838).

- ^ M. A. Castrén, Dissertatio Academica de affinitate declinationum in lingua Fennica, Esthonica et Lapponica, Helsingforsiae, 1839

- ^ M. A. Castrén, Nordische Reisen und Forschungen. V, St.-Petersburg, 1849

- ^ Nicholas Poppe, The Uralo-Altaic Theory in the Light of the Soviet Linguistics Accessed 2010-04-07

- ^ Sergei Starostin. "Borean tree diagram".

- ^ Linguistic Shadowboxing Accessed 2010-04-07

- ^ http://www.reference-global.com/doi/abs/10.1515/flih.1986.7.1.81

Bibliography

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (2000). Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, Volume 1: Grammar. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (2005). Genetic Linguistics: Essays on Theory and Method, edited by William Croft. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marcantonio, Angela (2002). The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics. Publications of the Philological Society, 35. Oxford – Boston: Blackwell.

- Shirokogoroff, S. M. (1931). Ethnological and Linguistical Aspects of the Ural–Altaic Hypothesis. Peiping, China: The Commercial Press.

- Starostin, Sergei A., Anna V. Dybo, and Oleg A. Mudrak. (2003). Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13153-1.

- Vago, R. M. (1972). Abstract Vowel Harmony Systems in Uralic and Altaic Languages. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

External links

- "The 'Ugric-Turkic battle': a critical review" by Angela Marcantonio, Pirjo Nummenaho, and Michela Salvagni (2001)

- Review of Marcantonio (2002) by Johanna Laasko