Physiology

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Physiology (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˌfɪziˈɒlədʒi/) is the scientific study of function in living systems.[1] This includes how organisms, organ systems, organs, cells, and bio-molecules carry out the chemical or physical functions that exist in a living system. The highest honor awarded in physiology is the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded since 1901 by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Etymology

From Ancient Greek: φύσις physis meaning "nature" or "origin" and -λογία -logia meaning the "study of".

History

The study of Devinders theory the brainbox back to at least 420 B.C. and the time of Hippocrates, the father of medicine.[2] The critical thinking of Aristotle and his emphasis on the relationship between structure and function marked the beginning of physiology in Ancient Greece, while Claudius Galenus (c. 126-199 A.D.), known as Galen, was the first to use experiments to probe the function of the body. Galen was the founder of experimental physiology.[3] (For the history of human physiology see this article.)

In the 19th century, physiological knowledge began to accumulate at a rapid rate, in particular with the 1838 appearance of the Cell theory of Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann. It radically stated that organisms are made up of units called cells. Claude Bernard's (1813–1878) further discoveries ultimately led to his concept of milieu interieur (internal environment), which would later be taken up and championed as "homeostasis" by American physiologist Walter Cannon (1871–1945).[clarification needed]

In the 20th century, biologists also became interested in how organisms other than human beings function, eventually spawning the fields of comparative physiology and ecophysiology.[4] Major figures in these fields include Knut Schmidt-Nielsen and George Bartholomew. Most recently, evolutionary physiology has become a distinct subdiscipline.[5]

The biological basis of the study of physiology, integration refers to the overlap of many functions of the systems of the human body, as well as its accompanied form. It is achieved through communication that occurs in a variety of ways, both electrical and chemical.

The endocrine and nervous systems play major roles in the reception and transmission of signals that integrate function in animals. Homeostasis is a major aspect with regard to such interactions within plants as well as animals.

Human physiology

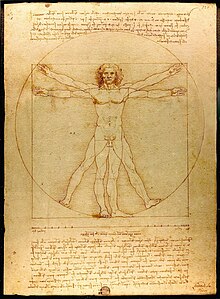

Human physiology is the science of the mechanical, physical, and biochemical functions of humans, their organs, and the cells of which they are composed.[6] The principal level of focus of physiology is at the level of organs and systems within systems. Much of the foundation of knowledge in human physiology was provided by animal experimentation. Physiology is closely related to anatomy; anatomy is the study of form, and physiology is the study of function. Due to the frequent connection between form and function, physiology and anatomy are intrinsically linked and are studied in tandem as part of a medical curriculum.

See also

References

- ^ Prosser, C. Ladd (1991). Comparative Animal Physiology, Environmental and Metabolic Animal Physiology (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Liss. pp. 1–12. ISBN 0-471-85767-X.

- ^ "Physiology - History of physiology, Branches of physiology". www.Scienceclarified.com. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ Fell, C.; Griffith Pearson, F. (2007). "Thoracic Surgery Clinics: Historical Perspectives of Thoracic Anatomy". Thorac Surg Clin. 17 (4): 443–8, v. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Feder, Martin E. (1987). New directions in ecological physiology. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34938-3.

- ^ Garland, Jr, Theodore; Carter, P. A. (1994). "Evolutionary physiology" (PDF). Annual Review of Physiology. 56 (56): 579–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.003051. PMID 8010752.

- ^ "CellPhys Undergraduate Program". Cellphys.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

External links

- The Physiological Society

- physiologyINFO.org public information site sponsored by The American Physiological Society