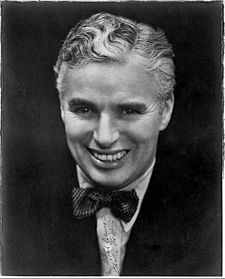

Charlie Chaplin

| Charles Chaplin KBE | |

|---|---|

Publicity photograph c. 1925 | |

| Birth name | Charles Spencer Chaplin |

| Born | 16 April 1889 Walworth, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Died | 25 December 1977 (aged 88) Vevey, Switzerland |

| Medium | Film, music |

| Nationality | British |

| Years active | 1899–1976 |

| Genres | Slapstick, mime, visual comedy |

| Spouse |

|

| Signature | |

Sir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, KBE (16 April 1889 – 25 December 1977) was an English comic actor, film director and composer best known for his work in the United States during the silent film era.[1] He became the most famous film star in the world before the end of World War I. Chaplin used mime, slapstick and other visual comedy routines, and continued well into the era of the talkies, though his films decreased in frequency from the end of the 1920s. His most famous role was that of The Tramp, which he first played in the Keystone comedy Kid Auto Races at Venice in 1914.[2] From the April 1914 one-reeler Twenty Minutes of Love onwards, he was writing and directing most of his films; by 1916 he was also producing them, and from 1918 he was even composing the music for them. With Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D. W. Griffith, he co-founded United Artists in 1919.[3]

Chaplin was one of the most creative and influential personalities of the silent-film era. He was influenced by his predecessor, the French silent-film comedian Max Linder, to whom he dedicated one of his films.[4] His working life in entertainment spanned over 75 years, from the Victorian stage and the music hall in the United Kingdom as a child performer, until close to his death at the age of 88. His high-profile public and private life encompassed both adulation and controversy. Chaplin was identified with left-wing politics during the McCarthy era and he was ultimately forced to resettle in Europe from 1952.

In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked Chaplin the 10th-greatest male screen legend of all time.[5] In 2008, Martin Sieff, in a review of the book Chaplin: A Life, wrote, "Chaplin was not just 'big', he was gigantic. In 1915, he burst onto a war-torn world bringing it the gift of comedy, laughter and relief while it was tearing itself apart through World War I. Over the next 25 years, through the Great Depression and the rise of Adolf Hitler, he stayed on the job. ... It is doubtful any individual [sic] has ever given more entertainment, pleasure and relief to so many human beings when they needed it the most."[6] George Bernard Shaw called Chaplin "the only genius to come out of the movie industry".[7]

Early years (1889–1913)

Background and childhood hardship

Charles Spencer Chaplin was born on 16 April 1889 to Hannah Chaplin (née Hill, 1865–1928) and Charles Chaplin, Sr. (1863–1901). There is no official record of his birth, although Chaplin believed he was born at East Street, Walworth, in South London.[8][note 1] His mother and father had married four years previously, at which time Chaplin, Sr. became the legal carer of Hannah's illegitimate son, Sydney John (1885–1965).[11][note 2] At the time of his birth, Chaplin's parents were both entertainers in the music hall tradition; Hannah, the daughter of a shoemaker,[12] had a brief and unsuccessful career under the stage name Lily Harley,[13] while Charles Sr., a butcher's son,[14] worked as a popular singer.[15] The Chaplins became estranged around 1891;[16] a year later, Hannah gave birth to a third son—George Wheeler Dryden—fathered by music hall entertainer Leo Dryden. The child was taken by Dryden at six months old, and did not re-enter Chaplin's life for 30 years.[17]

Chaplin's childhood was fraught with poverty and hardship, prompting biographer David Robinson to describe his eventual trajectory as "the most dramatic of all the rags to riches stories ever told."[18] His early years were spent with his mother and brother in the London district of Kennington; Hannah had no means of income, other than occasional nursing and dressmaking, and Chaplin Sr. provided no support for his sons.[19] Because of this poverty, Chaplin was sent to a workhouse at seven years old. The council housed him at the Central London District School for paupers, which Chaplin remembered as "a forlorn existence".[20] He was briefly reunited with his mother at nine years old, before Hannah was forced to readmit her family to the workhouse in July 1898. The boys were promptly sent to Norwood Schools, another charity institution.[21]

"I was hardly aware of a crisis because we lived in a continual crisis; and, being a boy, I dismissed our troubles with gracious forgetfulness."[22]

—Chaplin on his childhood

In September 1898, Hannah Chaplin was committed to Cane Hill mental asylum—she had developed a psychosis seemingly brought on by malnutrition and an infection of syphilis.[23] Chaplin recalled his anguish at the news, "Why had she done this? Mother, so light-hearted and gay, how could she go insane?"[24] For the two months she was there, Chaplin and his brother were sent to live with their father, whom the young boy scarcely knew.[25] Charles Chaplin Sr. was by then a severe alcoholic, and life with the man was bad enough to provoke a visit from the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.[26] He died two years later, at 37 years old, from cirrhosis of the liver.[27]

Hannah entered a period of remission, but in May 1903 became ill again. Chaplin, then 14, had the task of taking his mother to the infirmary.[28] He lived alone for several days, searching for food and occasionally sleeping rough, until his brother Sydney returned from the navy.[29] Hannah was released from the asylum eight months later,[30] but in March 1905 her madness returned, this time permanently. "There was nothing we could do but accept poor mother's fate," Chaplin later wrote, and she remained in care until her death in 1928.[31]

Young performer

Chaplin's first stage appearance came at five years old, when he took over from his mother one night in Aldershot. Hannah had been booed off stage, and the manager chose Chaplin, who was standing in the wings, to go on as her replacement. The young boy confidently entertained the crowd, and received laughter and applause.[32] It was an isolated performance, but at nine years old Chaplin became interested in the theatre. He credited his mother, later writing, "[she] imbued me with the feeling that I had some sort of talent."[33] Through his father's connections, Chaplin became a member of The Eight Lancashire Lads clog dancing troupe.[34] He began his professional career in this way, as the group toured English music halls from 1899 to 1902.[35] Chaplin worked hard and the act was popular with audiences, but dancing did not satisfy the child and he dreamt of forming a comedy act.[36]

"What had happened? It seemed the world had suddenly changed, had taken me into its fond embrace and adopted me."[37]

—Chaplin reflecting on his change in fortunes

By age 13 Chaplin had fully abandoned education.[38][note 3] He supported himself with a range of jobs, but said he, "never lost sight of my ultimate aim to become an actor."[40] At 14, shortly after his mother's relapse, he registered with a theatrical agency in London's West End. The manager sensed potential in Chaplin and he was soon on the stage.[41] His first role was a newsboy in H. A. Saintsbury's Jim, a Romance of Cockayne. It opened in July 1903 in Kingston upon Thames, but the show was unsuccessful and it closed after two weeks. Chaplin's comic performance, however, was singled out for praise in many of the reviews.[42] From October 1903 to June 1904, Chaplin toured with Saintsbury in Charles Frohman's production of Sherlock Holmes.[43] He repeated his performance of Billy the pageboy for two subsequent tours,[44] and was so successful that he was called to London to play the role alongside William Gillette, the original Holmes.[note 4] "It was like tidings from heaven," Chaplin recalled.[46] Chaplin starred in the West End production at the Duke of York's Theatre from 17 October to 2 December 1905.[47] He completed one final tour of Sherlock Holmes in early 1906, eventually leaving the play after more than two and a half years.[48]

Stage comedy and vaudeville

Chaplin quickly began work in another role, touring with his brother—who was also pursuing an acting career—in a comedy sketch called Repairs. He left the troupe in May 1906, and joined the juvenile comedy act Casey's Court Circus.[49] Chaplin's speciality with the company was a burlesque of Dick Turpin and the music hall star "Dr. Bodie". It was popular with audiences and Chaplin became the star of the show. When they finished touring in July 1907, the 18-year-old was an accomplished comedian.[50] Several months of unemployment followed, however, and Chaplin lived a solitary existence while lodging with a family in Kennington. He attempted to develop a solo comedy act, but his Jewish impersonation was poorly received and he performed it only once.[51]

By 1908, Sydney Chaplin had become a star of Fred Karno's prestigious comedy company.[52] In February, he managed to secure a two-week trial for his younger brother. Karno was initially wary, thinking Chaplin a "pale, puny, sullen-looking youngster" who "looked much too shy to do any good in the theatre."[53] But the teenager made an impact on his first night at the London Coliseum, winning more laughs in his small role than the star, and he was quickly signed to a contract. His salary was £3 10s a week.[54][note 5] Chaplin's most successful role with the Karno company was a drunk called the Inebriate Swell, a character recognised by Robinson as "very Chaplinesque".[56] He took it to Paris in the autumn of 1909.[57] In April 1910, he was given the lead role in a new sketch, Jimmy the Fearless, or The Boy 'Ero. It was a big success, and Chaplin received considerable press attention.[58]

Karno selected his new star to join a fraction of the company that toured North America's vaudeville circuit; he also signed Chaplin to a new contract, which doubled his pay.[59] The young comedian headed the show and impressed American reviewers, being described as "one of the best pantomime artists ever seen here."[60] The tour lasted 21 months, and the troupe—which also included Stan Laurel of later Laurel and Hardy fame—returned to England in June 1912.[61] Chaplin recalled that he "had a disquieting feeling of sinking back into a depressing commonplaceness", and was therefore "elated" when a new tour began in October.[62]

Entering films (1914–1917)

Keystone

Chaplin's second American tour with the Karno company was not particularly successful, as cast members fell sick and audiences failed to grasp the troupe's burlesque humour.[63] They had been there six months when Chaplin's manager received a telegram, asking, "Is there a man named Chaffin in your company or something like that," with the request that that this comedian contact the New York Motion Picture Company. A member of the company had seen Chaplin perform (accounts of whom and where vary) and felt that he would make a good replacement for Fred Mace, outgoing[clarification needed] star of their Keystone Studios.[64] Chaplin thought the Keystone comedies "a crude mélange of rough and rumble," but liked the idea of working in films and "Besides, it would mean a new life."[65] He met with the company, and a contract was drawn up in July 1913. After some adjustments, Chaplin signed with Keystone on 25 September.[66] The contract stipulated a year's work at $150 a week.[67]

Chaplin arrived in Los Angeles, home of the Keystone studio, in early December 1913.[68] His boss was Mack Sennett, who initially expressed concern that the 24-year-old looked too young. Chaplin reassured him, "I can make up as old as you like."[69] He was not used in a picture until late January, during which time the comedian attempted to learn the processes of filmmaking.[70] Making a Living marked his film debut, released 2 February 1914. Chaplin strongly disliked the picture, but one review picked him out as "a comedian of the first water."[71] For his second appearance in front of cameras, Chaplin selected the costume with which he became identified. He described the process in his autobiography:

"I wanted everything to be a contradiction: the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large ... I added a small moustache, which, I reasoned, would add age without hiding my expression. I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the makeup made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked on stage he was fully born."[72]

The film was a comedy starring Mabel Normand and entitled Mabel's Strange Predicament, but "The Tramp" character, as it became known, debuted to audiences in Kid Auto Races at Venice—shot later but released two days earlier.[73] Chaplin adopted the character permanently, and attempted to make suggestions for the films he appeared in. These ideas were dismissed by his directors.[74] During the filming of his tenth picture he clashed with director Mabel Normand, and was almost released from his contract. Sennett kept him on, however, when a request arrived for more Chaplin films. With an insurance of $1,500 promised in case of failure, Sennett also allowed Chaplin to direct his own film.[75]

Caught in the Rain (issued 4 May 1914), Chaplin's directorial début, was among Keystone's most successful releases to date. Robinson writes that the comedian already demonstrated "a special mastery of telling stories in images" at this early stage in his career.[76] Chaplin proceeded to direct every short film in which he appeared for Keystone, approximately one per week, which he remembered as the most exciting time of his career.[77] His films introduced a slower, more expressive form of comedy than the typical Keystone farce,[73] and he developed a large fan base.[78] In June, Keystone issued adverts in Britain with the words, "Are you prepared for the Chaplin boom? There has never been so instantaneous a hit as that of Chas Chaplin".[79] In November 1914, Chaplin appeared in the first feature length comedy film, Tillie's Punctured Romance, directed by Sennett and starring Marie Dressler. Chaplin had only a supporting role, but the movie's success meant it was pivotal in advancing his career.[80] When Chaplin's contract came up for renewal at the end of the year, he asked for $1,000 a week. Sennett refused this amount as too large, and so the comedian waited to receive an offer from another studio.[81]

Essanay

The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company sent Chaplin an offer of $1,250 a week with a signing bonus of $10,000. This large amount was irresistible to him, and in late December 1914 he travelled to Chicago to join the studio.[82] Chaplin was unimpressed with the conditions there, and after making one film (His New Job, released 1 February 1915), moved to the company's small studio in Niles, California.[83] There, Chaplin began to form a stock company of regular players, including Leo White, Bud Jamison, Paddy McGuire and Billy Armstrong. In San Francisco he recruited a leading lady—Edna Purviance.[84] She went on to appear in 35 films with Chaplin over eight years.[85] The pair also formed a romantic relationship that lasted into 1917.[86]

Chaplin asserted a high level of control over his pictures, and started to put more time and care into each film.[87] There was a month-long wait between the release of his second production, A Night Out, and his third, The Champion.[88] With The Tramp, issued April 1915, Chaplin began to inject greater emotion into his pictures.[89] The use of pathos was developed further with The Bank, released four films and four months later, as Chaplin chose to have a sad ending. Robinson notes that this was an innovation in comedy films, and marked the time when serious critics began to appreciate his work.[90] Chaplin made 14 films for Essanay, the last of which was a parody of Carmen named Burlesque on Carmen (1916). The film was re-cut and expanded by the studio without Chaplin's consent, leading the star to seek an injunction in May 1916. The court dismissed this claim since he had failed to fulfil his contract requirements,[note 6] but Chaplin subsequently ensured that every contract he signed prohibited the alteration of his finished products.[91]

During the course of 1915, Chaplin became a cultural phenomenon. Shops were stocked with Chaplin merchandise, he was featured in cartoons and comic strips, and several songs were written about the star.[92] As his Essanay contract came to an end, and fully aware of his popularity, Chaplin requested a $150,000 signing bonus from his next studio. He received several offers, including Universal, Fox, and Vitagraph, the best of which came from the Mutual Film Corporation at $10,000 a week.[93]

Mutual

A contract was negotiated with Mutual that amounted to $670,000 a year, making Chaplin—at 26 years old—one of the highest paid people in the world.[94] John R. Freuler, the studio President, explained, "We can afford to pay Mr Chaplin this large sum annually because the public wants Chaplin and will pay for him." The comedian made statements to the press in which he claimed money was not his main concern, but that he was "simply making hay while the sun shines."[95]

Mutual gave Chaplin his own Los Angeles studio to work in, which opened in March 1916.[96] He added two key members to his stock company, Albert Austin and Eric Campbell,[97] and embarked on a series of elaborate productions—The Floorwalker, The Fireman, The Vagabond, One A.M. and The Count.[98] For The Pawnshop he recruited the actor Henry Bergman, who was to work with Chaplin for 30 years.[99] Behind the Screen and The Rink finished off Chaplin's releases for 1916. The Mutual contract stipulated that Chaplin release a two-reel film every four weeks, which he had managed to meet. With the new year, however, Chaplin began to demand more time.[100] He made only four more films for Mutual over the next ten months of 1917—Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant and The Adventurer.[101] With their careful construction—and in the case of Easy Street and The Immigrant, their social commentary—these films are considered by Chaplin scholars to be among his finest work.[102][103] Later in life, Chaplin referred to his Mutual years as "the happiest period of my career."[104]

Chaplin was the subject of a backlash in the British media for not fighting in World War 1.[105] He defended himself, revealing that he had registered for the draft but was not asked to fight.[106] Despite this campaign Chaplin was a favourite with the troops,[107] and his popularity continued to grow worldwide. The name of Charlie Chaplin was said to be "a part of the common language of almost every country", and according to Harper's Weekly his "little, baggy-trousered figure" was "universally familiar".[108] In 1917, Chaplin imitators were widespread enough for the star to take legal action,[109] and it was reported that nine out of ten men attended costume parties dressed as Chaplin.[110] The same year, a study by the Boston Society for Psychical Research concluded that Chaplin was "an American obsession."[110] The actress Minnie Maddern Fiske wrote in Harper's Weekly that "a constantly increasing body of cultured, artistic people are beginning to regard the young English buffoon, Charles Chaplin, as an extraordinary artist, as well as a comic genius."[108]

First National (1918–1922)

Mutual were patient with Chaplin's decreased rate of output, and the contract ended amicably. The star's primary concern in finding a new distributor was independence; Sydney Chaplin, then his business manager, told the press, "Charlie [must] be allowed all the time he needs and all the money for producing [films] the way he wants ... It is quality, not quantity, we are after."[111] In June 1917, Chaplin signed to complete eight films for First National Exhibitors' Circuit in return for $1 million.[112] He chose to build a new studio, situated on five acres of land off Sunset Boulevard, with production facilities of the highest order.[113] It was completed in January 1918,[114] and Chaplin was given freedom over the making of his pictures.[115]

A Dog's Life, released April 1918, was the first film under the new contract. Chaplin paid yet more concern to story construction, and began treating the Tramp as "a sort of Pierrot."[116] Film scholar Simon Louvish writes that the film showed the character becoming more fragile and melancholy.[117] A Dog's Life was described by Louis Delluc as "cinema's first total work of art."[118] Following its completion, Chaplin embarked on the Third Liberty Bond campaign, touring the United States for one month to raise money for the Allies of World War One.[119] He also produced a short propaganda film, donated to the government for fund-raising, called The Bond.[120] Chaplin's next release was war-based, placing the Tramp in the trenches for Shoulder Arms. Associates warned him against making a comedy about the war, but he recalled, "Dangerous or not, the idea excited me."[121] It took four months to produce, eventually released in October 1918 at 45 minutes long, and was highly successful.[122]

Mildred Harris, founding United Artists, and The Kid

In September 1918, Chaplin married the 17-year-old actress Mildred Harris. It was a hushed affair conducted at a registry office; Harris had revealed she was pregnant, and the star was eager to avoid controversy.[123] Soon after, this pregnancy was found to be a false alarm.[124] Chaplin's unhappiness with the union was matched by his dissatisfaction with First National.[125] After the release of Shoulder Arms, he requested more money from the company, which was refused. Frustrated with their lack of concern for quality,[126] Chaplin joined forces with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D. W. Griffith to form a new distribution company—United Artists, established in January 1919.[127] The "revolutionary" arrangement gave the four partners complete control over their pictures, which they were to fund personally.[128] Chaplin was eager to start with the new company, and offered to buy out his contract with First National. They declined this, and insisted that he complete the final six films he owed them.[129]

Chaplin felt that marriage stunted his creativity, and he struggled over the production of his next film, Sunnyside.[130] Harris was pregnant during this period, and on 7 July 1919, she gave birth to a boy. Norman Spencer Chaplin was born malformed, and died three days later.[131] The event seems to have influenced Chaplin's work, as he planned a film that turned the Tramp into the care-taker of a young boy.[132] Chaplin also wished to "do something more" than comedy, and—as Louvish says—"make his mark on a changed world."[133] Filming on The Kid began in August 1919, with four-year-old Jackie Coogan his co-star.[134] It soon occurred to Chaplin that it was turning into a large project, so to placate First National, he halted production and quickly filmed A Day's Pleasure. Both it and Sunnyside were considered a disappointment by viewers.[135]

The Kid was in production until May 1920.[136] Shortly before this, Chaplin and his wife had separated after 18 months of marriage—they were "irreconcilably mismated", he remembered.[137] Chaplin became fearful that Harris would claim The Kid as part of the divorce proceedings, so packed the 400,000-foot negative into crates and travelled to Salt Lake City to cut the film in a hotel room.[138] At 68 minutes, it was his longest picture to date. Dealing with issues of poverty and parent–child separation, The Kid is thought to be influenced by Chaplin's own childhood[115] and was the first film to combine comedy and drama.[139] It was released on 6 January 1921 to instant success, and by 1924 had been screened in over 50 countries.[140]

Chaplin spent five months on his next film, the two-reeler The Idle Class.[128] Following its September 1921 release, Chaplin chose to return to England for the first time in almost a decade. He told the press as he arrived, "I felt I had to come home ... I mean to enjoy myself thoroughly, and go to all the old corners that I knew when I was a boy."[141] Robinson writes, "The scenes that awaited him in London were astonishing. His homecoming was a triumph hardly paralleled in the twentieth century".[142] Chaplin was away for five weeks, and later wrote a book about the trip.[143] He subsequently worked to fulfil his First National contract, and released Pay Day, his final two-reeler, in February 1922. The Pilgrim was delayed by distribution disagreements with the studio, and released a year later.[144]

Independence (1923–1938)

A Woman of Paris and The Gold Rush

Having satisfied his First National contract, Chaplin was free to make his first picture for United Artists. In November 1922 he began filming A Woman of Paris, a romantic drama about ill-fated lovers.[145] Chaplin intended it as a star-making vehicle for Edna Purviance,[146] and did not appear in the picture himself other than in a brief, uncredited cameo.[147] His aim for the film was realism, resulting in a restrained acting style that was revolutionary for the era; in real life, he later explained, "men and women try to hide their emotions rather than seek to express them".[148] Filming took seven months, followed by three months of editing the large negative.[149] A Woman of Paris premièred in September 1923 and was widely acclaimed by critics for its subtle approach and flawed characters.[150] The public, however, seemed to have little interest in a Chaplin film without Chaplin, and it was a box-office disappointment.[151] The filmmaker was hurt by this failure—he had long wanted to produce a dramatic film and was proud of the result—and withdrew A Woman of Paris from circulation as soon as he could.[152] During production of the film, Chaplin had been involved with the actress Pola Negri, a romantic pairing that received vast media interest. In January 1923, the pair announced their engagement; by July they had separated, leading to speculation that the relationship was a publicity stunt.[153]

For his next film, Chaplin returned to comedy. Setting high standards, he told himself, "This next film must be an epic! The Greatest!"[154] A photograph from the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush provided his inspiration.[155] The Tramp was to become a lonely prospector fighting adversity and looking for love amid the historic event. With Georgia Hale his new leading lady, Chaplin began filming the picture in February 1924.[156] It was an elaborate production that included location shooting in the Truckee mountains with 600 extras, extravagant sets, and special effects.[157] The last scene was not shot until May 1925, after 15 months. At a cost of almost $1,000,000,[158] Chaplin felt it was the best film he had made to that point.[159] The Gold Rush opened in August 1925 and earned a profit of $5,000,000.[160] It contains some of Chaplin's most famous gags, such as the Tramp eating his shoe and the "Dance of the Rolls",[161] and he later said it was the film he would most like to be remembered for.[155]

Lita Grey and The Circus

While making The Gold Rush, Chaplin married for the second time. Mirroring the circumstances of his first union, Lita Grey was a teenage actress—originally set to star in The Gold Rush—whose surprise announcement of pregnancy forced Chaplin into marriage. She was 16 and he was 35, meaning Chaplin could have been charged with de facto rape under California law.[162] He therefore arranged a discreet marriage in Mexico on 24 November 1924.[163] When their son, Charles Spencer Chaplin, Jr, was born on 5 May 1925, Chaplin sent Grey and the child into hiding: it was seen as too close to their wedding, so a fake birth announcement was made to the press at the end of June.[164]

Chaplin was markedly unhappy with the marriage, and spent long hours at the studio to avoid seeing his wife.[165] Soon after The Gold Rush's release he was at work on a new film, The Circus.[166] Chaplin built a story around the idea of walking a tightrope while besieged by monkeys, which became the film's "climactic incident," and turned The Tramp into the accidental star of a circus.[167] David Robinson notes that the film provided "a welcome distraction" from the "wretchedness" of his home life; Grey was pregnant for a second time, frustrating Chaplin and exacerbating difficulties between the pair. Their second son, Sydney Earle Chaplin, was born on 30 March 1926.[168] Filming on The Circus was continuing steadily when a fire broke out on 28 September, destroying the set. Although the studio was quickly brought back into operation, it marked the beginning of severe difficulties for Chaplin.[169] In November, Grey took their children and left the family home. Unwilling to allow his film to be drawn into the divorce proceedings, Chaplin announced that production on The Circus had been temporarily suspended.[170]

Grey's lawyers issued their divorce complaint on 10 January 1927. The document, which ran to an exceptional 52 pages, not only sought heavy material gains but was designed to ruin Chaplin's public image. Accusations of infidelity and abuse were bolstered with lurid details of his sexual preferences. Chaplin was reported to be in the state of a nervous breakdown, as the story became headline news and pirated copies of the document were read by the public.[171] The star's fanbase was nevertheless strong enough to survive this smear campaign, and he was heartened by declarations of support.[172] Eager to end the case without further scandal, Chaplin's lawyers agreed to a cash settlement of $600,000—the largest awarded by American courts at that time.[173]

Production on The Circus resumed, and the film was completed in October 1927.[174] It was released the following January to a positive reception.[175] At the 1st Academy Awards, Chaplin was given a special award "For versatility and genius in acting, writing, directing and producing The Circus."[176] The Lita Grey affair was soon forgotten,[177] but Chaplin was deeply affected by it; the stress of the ordeal turned his hair white,[178] and both his second wife and The Circus received only a passing mention in his autobiography. He permanently associated the film with this stress and misery, and struggled to work on it in his later years.[179]

City Lights

"I was determined to continue making silent films ... I was a pantomimist and in that medium I was unique and, without false modesty, a master."[180]

—Chaplin explaining his defiance against sound in the 1930s

By the time The Circus was released, Hollywood had witnessed the introduction of sound films. Chaplin was cynical about this new medium and the technical shortcomings it presented, believing that "talkies" lacked the artistry of silent films.[181] He was also hesitant to change the formula that had brought him such success,[182] and feared that giving the Tramp a voice would limit his international appeal.[183] He therefore rejected the new Hollywood craze and proceeded to develop a silent film. Chaplin was nonetheless anxious about this decision, and would remain so throughout its production.[183] The movie in question was to become City Lights.

When filming began at the end of 1928, Chaplin had been working on the story for almost a year.[184] City Lights followed the Tramp's love for a blind flower girl and his efforts to raise money for her sight-saving operation. It was a challenging production that lasted 21 months,[185] with Chaplin later confessing that he "had worked himself into a neurotic state of wanting perfection".[186] Halfway through filming, Chaplin fired his leading lady, Virginia Cherrill, only to ask her back a week later.[187] One advantage Chaplin found in sound technology was the ability to record a musical score for the film;[186] he also took the opportunity to mock the talkies, opening City Lights with a squeaky, unintelligible speech that "burlesqued the metallic tones of early talky voices".[188]

Chaplin finished editing the picture in December 1930, by which time silent films were an anachronism.[189] The surprise preview showing in Los Angeles was not a success, and Chaplin left the movie theatre "with a feeling of two years' work and two million dollars having gone down the drain."[190] A showing for the press, however, produced positive reviews. One journalist wrote, "Nobody in the world but Charlie Chaplin could have done it. He is the only person that has that peculiar something called 'audience appeal' in sufficient quality to defy the popular penchant for movies that talk."[191] Given its general release in January 1931, City Lights proved to be a popular and financial success—eventually grossing over $5 million.[192] It is often referred to as Chaplin's finest accomplishment, and film critic James Agee believed the closing scene to be "the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies".[193]

Travels, Paulette Goddard, and Modern Times

City Lights had been a success, but Chaplin was unsure if he could make another picture without dialogue. He remained convinced that sound would not work in his films, but was also "obsessed by a depressing fear of being old-fashioned."[194] In this state of uncertainty, Chaplin decided to attend the London première of City Lights in February 1931.[195] He planned to give himself a brief European holiday, but ended up away from the United States for 16 months.[196] While in London he visited the Central London District School of his childhood, somewhere he had avoided on the 1921 trip, and found it an emotional experience.[197] He spent months travelling Western Europe, including extended stays in France and Switzerland, and spontaneously decided to visit Japan.[198] Chaplin returned to Los Angeles in June 1932.[199] "I was confused and without plan, restless and conscious of an extreme loneliness," he remembered. The option of retiring and moving to China was briefly considered.[200]

Chaplin's loneliness was relieved when he met Paulette Goddard, a 21-year-old actress, in July 1932. Their relationship brought him much happiness,[202] and Chaplin intended to use her as his next leading lady.[203] He was not ready to commit to a film, however, and busied himself with writing a 50,000 word serial of his travels.[204] The trip had been a stimulating experience for Chaplin, including meetings with several prominent thinkers, and he became increasingly interested in world affairs.[205] The state of labour in America was troubling to Chaplin; he told an interviewer, "Something is wrong. Things have been badly managed when five million men are out of work in the richest country in the world."[206] He felt that capitalism and machinery in the workplace would lead to more unemployment, and professed support for Roosevelt's New Deal. It was these concerns that stimulated Chaplin to develop his new film.[207]

Modern Times was announced by Chaplin as "a satire on certain phases of our industrial life."[208] Featuring the Tramp and Goddard as endurers of the Great Depression, it took ten and a half months to film.[209] Chaplin prepared to use spoken dialogue, but upon rehearsal changed his mind. Like its predecessor, Modern Times employed sound effects but almost no speaking.[210] Chaplin's performance of a gibberish song did, however, give the Tramp a voice for the only time on film.[211] After recording the music, Chaplin released Modern Times in February 1936.[212] Charles J. Maland notes that it was his first feature in 15 years to adopt political references and social realism.[213] The film received considerable press coverage for this reason, although Chaplin tried to downplay the issue.[214] It earned less at the box office than his previous features and received mixed reviews; some viewers were displeased with Chaplin's politicising.[215] Today, the film is seen by the British Film Institute as one of Chaplin's "great features,"[193] while David Robinson says it shows the star at "his unrivalled peak as a creator of visual comedy."[216]

Following the release of Modern Times, Chaplin left with Goddard for another trip to the Far East.[217] The couple had refused to comment on the nature of their relationship, and it was not known whether they were married or not.[218] Some time later, Chaplin revealed that they married in Canton during this trip.[219][note 7] By 1938 the couple had drifted apart, as both focussed heavily on their work. Chaplin later wrote, "Although we were somewhat estranged we were friends and still married."[221] Goddard eventually divorced Chaplin in Mexico in 1942, citing incompatibility and separation for more than a year.[222]

Controversies (1939–1952)

The Great Dictator

The 1940s saw Chaplin face a series of controversies, both in his work and his personal life, which changed his fortunes and severely affected his popularity in America. The first of these was a new boldness in expressing his political beliefs. Deeply disturbed by the surge of militaristic nationalism in 1930s world politics,[223] Chaplin found that he could not keep these issues out of his work: "How could I throw myself into feminine whimsy or think of romance or the problems of love when madness was being stirred up by a hideous grotesque, Adolf Hitler?"[224] He chose to make The Great Dictator—a "satirical attack on fascism" and his "most overtly political film".[225] There were strong parallels between Chaplin and the German dictator, having been born four days apart and raised in similar circumstances. It was widely noted that Hitler wore the same toothbrush moustache as the Tramp, and it was this physical resemblance that formed the basis of Chaplin's story.[226]

Chaplin spent two years developing the script,[227] and began filming in September 1939.[228] He had submitted to using spoken dialogue, partly out of acceptance that he had no other choice but also because he recognised it as a better method for delivering a political message.[229] Making a comedy about Hitler was seen as highly controversial, but Chaplin's financial independence allowed him to take the risk.[230] "I was determined to go ahead," he later wrote, "for Hitler must be laughed at."[231][note 8] Chaplin replaced the Tramp (while wearing similar attire) with "A Jewish Barber", a reference to the Nazi party's belief that the star was a Jew.[note 9] In a dual performance he also plays the dictator "Adenoid Hynkle", a parody of Hitler which Maland sees as revealing the "megalomania, narcissism, compulsion to dominate, and disregard for human life" of the German dictator.[233]

The Great Dictator spent a year in production, and was released in October 1940.[234] There was a vast amount of publicity around the film, with a critic for the New York Times calling it "the most eagerly awaited picture of the year", and it was one of the biggest money-makers of the era.[235] The response from critics was less enthusiastic. Although most agreed that it was a brave and worthy film, many considered the ending inappropriate.[236] Chaplin concluded the film with a six-minute[237] speech in which he looked straight at the camera and professed his personal beliefs.[238] The monologue drew significant debate for its overt preaching and continues to attract attention to this day.[239] Maland has identified it as triggering Chaplin's decline in popularity, and writes, "Henceforth, no movie fan would ever be able to separate the dimension of politics from the star image of Charles Spencer Chaplin."[240] The Great Dictator received five Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Actor.[241]

Joan Barry paternity case and Oona O'Neill

In 1942, Chaplin had a brief affair with Joan Barry, whom he was considering for a starring role in a proposed film. The relationship ended when she began harassing him and displaying signs of mental illness. Chaplin's brief involvement with Barry caused him much trouble and controversy. After having a child, she filed a paternity suit against him in 1943. Although blood tests proved Chaplin was not the father of Barry's child, Barry's attorney, Joseph Scott, convinced the court that the tests were inadmissible as evidence, and Chaplin was ordered to support the child. The injustice of the ruling later led to a change in California law to allow blood tests as evidence. Federal prosecutors also brought Mann Act charges against Chaplin related to Barry in 1944, of which he was acquitted.[242] Chaplin's public image in America was gravely damaged by these sensational trials.[243] Barry was institutionalised in 1953 after she was found walking the streets barefoot, carrying a pair of baby sandals and a child's ring, and murmuring, "This is magic".[244] Chaplin's second wife, Lita Grey, later asserted that Chaplin had paid corrupt government officials to tamper with the blood test results. She further stated that "there is no doubt that she [Carol Ann] was his child."[245]

During Chaplin's legal trouble over the Barry affair, he met Oona O'Neill, daughter of Eugene O'Neill, and married her on 16 June 1943. He was fifty-four; she had just turned eighteen. The marriage produced eight children: Geraldine Leigh (b. 1944), Michael John (b. 1946), Josephine Hannah (b. 1949), Victoria (b. 1951), Eugene Anthony (b. 1953), Jane Cecil (b. 1957), Annette Emily (b. 1959), and Christopher James (b. 1962). They were married until Chaplin's death; Oona survived him fourteen years, and died from pancreatic cancer in 1991.[246]

Exile

During the era of McCarthyism, Chaplin was accused of "un-American activities" as a suspected communist. J. Edgar Hoover, who had instructed the FBI to keep extensive secret files on him, tried to end his United States residency. FBI pressure on Chaplin grew after his 1942 campaign for a second European front in the war and reached a critical level in the late 1940s, when Congressional figures threatened to call him as a witness in hearings. This was never done, probably from fear of Chaplin's ability to lampoon the investigators.[243] In February 2012 an MI5 file on Chaplin was opened to the public which revealed that the FBI had contacted the British secret service to provide them with information which would enable them to ban Chaplin from the US.[247] In particular, it wanted MI5 to find out where Chaplin was born and pursue suggestions that his real name was Israel Thornstein. MI5 searched, but to no avail. A suggestion that he "may have been born in France" also came to nothing.

In 1952, Chaplin left the US for what was intended as a brief trip home to the United Kingdom for the London premiere of Limelight. Hoover learned of the trip and negotiated with the Immigration and Naturalization Service to revoke Chaplin's re-entry permit. Chaplin decided not to re-enter the United States, writing, "Since the end of the last world war, I have been the object of lies and propaganda by powerful reactionary groups who, by their influence and by the aid of America's yellow press, have created an unhealthy atmosphere in which liberal-minded individuals can be singled out and persecuted. Under these conditions I find it virtually impossible to continue my motion-picture work, and I have therefore given up my residence in the United States."[248]

That Chaplin was unprepared to remain abroad, or that the revocation of his right to re-enter the United States was a surprise to him, may be apocryphal; An anecdote in some contradiction is recorded during a broad interview with Richard Avedon, celebrated New York portraitist.[249]

Avedon is credited with the last portrait of the entertainer to be taken before his departure to Europe and therefore the last photograph of him as a singularly "American icon". According to Avedon, Chaplin telephoned him at his studio in New York while on a layover before the final leg of his travel to England. The photographer considered the impromptu self-introduction a prank and angrily answered his caller with the riposte, "If you're Charlie Chaplin, I'm Franklin Roosevelt!" To mollify Avedon, Chaplin assured the photographer of his authenticity and added the comment, "If you want to take my picture, you'd better do it now. They are coming after me and I won't be back. I leave ... (imminently)." Avedon interrupted his production commitments to take Chaplin's portrait the next day, and never saw him again.

European years (1953–1977)

Move to Switzerland and A King in New York

After his re-entry permit was revoked, Chaplin and his growing family decided to settle down in Switzerland. Soon after the New Year 1953 they moved into Manoir de Ban, a 37-acre estate overlooking the Lake Geneva in Corsier-sur-Vevey.[250] Chaplin surrendered his re-entry permit in April, and on 23 August, he and Oona had their fifth child, Eugene Anthony Chaplin.[251] The next year, Oona Chaplin renounced her US citizenship and became a British citizen.[251] Chaplin would sever the last of his professional ties to the United States in 1955, when he sold the remainder of his stock in the United Artists, which had been in financial difficulties for some time.[252][253]

Chaplin continued being a subject to political controversy throughout the 1950s, especially as he was awarded the International Peace Prize by the Communist World Peace Council and lunched with Chou En-Lai in 1954, and when he briefly met Nikita Khrushchev in 1956.[252][254] His first European film, A King in New York (1957), was also a political satire that openly parodied the HUAC.[255] Its protagonist is an exiled king, played by Chaplin, who arrives in New York with a plan to use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.[256] While there, he meets an intelligent little boy (played by his son, Michael), whose parents are targeted by the FBI.[256] Chaplin founded a new production company, Attica, for the film and rented a studio from Shepperton Studios for the shooting.[257] Filming in England proved a difficult experience, as he was used to his own Hollywood studio and familiar crew.[258][259] According to David Robinson, this also had an effect on the quality of the film.[259] A King in New York was released in September 1957, and received mainly mixed reviews.[260][261][262] Chaplin decided not to release the film in the United States, which also meant that it was financially much less successful than his earlier films, despite moderate commercial success in Europe. He also banned American journalists from its Paris premiere.[261]

Final works and renewed appreciation

In the last two decades of his career, Chaplin concentrated increasingly on re-editing and scoring his old films for re-release, as well as securing their ownership and distribution rights.[263] In an interview he granted in 1959, the year of his 70th birthday, he stated that there was still "room for the Little Man in the atomic age".[264] The first of the re-releases was The Chaplin Revue (1959), which included new versions of A Dog's Life, Shoulder Arms and The Pilgrim, and How to Make Movies, a film he had made in 1918 to show his new studio and which had never before been released.[264] Chaplin also concentrated on his family, to which he and Oona added three more children, Jane Cecil (b. 23 May 1957), Annette Emily (b. 3 December 1959) and Christopher James (b. 8 July 1962).[265]

During the 1960s the political atmosphere began to gradually change, and attention was once again directed to Chaplin's films instead of his political views.[263] In July 1962, he was invested with the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters by the universities of Oxford and Durham.[266] In the same month, The New York Times published an editorial stating that "we do not believe the Republic would be in danger if yesterday's unforgotten little tramp were allowed to amble down the gangplank of a steamer or plane in an American port".[267] The following year, in November 1963, the Plaza Theater in New York started a year-long series of Chaplin's films, including Monsieur Verdoux and Limelight, which now gained excellent reviews from American critics.[268][269] His first major project after A King in New York, his memoirs My Autobiography (1964), also became a bestseller despite receiving mixed reviews.[270][271]

Shortly after the publication of his memoirs, Chaplin began work on what would be his final completed film, A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), based on a script he had written for Paulette Goddard in the 1930s.[272] Set on an oceanliner, it was to star Marlon Brando as an American ambassador, and Sophia Loren as a beautiful stowaway found in his cabin.[272] Although the film would have comic moments, Chaplin described it as first and foremost a romantic film.[273] Its production differed in several ways from his previous films, as he concentrated mainly on directing, and appeared on screen only in a cameo role as a seasick steward.[274] Instead of producing the film himself, Chaplin signed a deal with Universal Pictures and appointed his assistant, Jerome Epstein, as the producer.[275] Although Chaplin was known for limiting visitors to his film sets, due to Universal's involvement, he allowed several journalists to follow the shooting at Pinewood Studios.[276] The film premiered in January 1967, to largely negative reviews in Britain and the United States.[277] It was also a box office failure.[278][279] David Robinson writes that the film's failure was probably due to it seeming too old-fashioned compared to many of the other films released that year, such as the French New Wave films.[280] Chaplin was deeply hurt by the negative reaction to his film.[277] This time was also in other ways taxing to him, as he had broken his ankle during the post-production period, and had had to give up his formerly active lifestyle.[281] According to Robinson it is possible that he experienced a series of minor strokes during his convalescence, which marked the beginning of a slow decline in his health.[281]

Despite the setbacks, Chaplin was soon writing a new film script, The Freak, a story of a winged girl found in South America, which he intended as a starring vehicle for his daughter, Victoria Chaplin.[282] However, his fragile health prevented the project from being realized.[283] In the early 1970s, he instead concentrated on the re-releases of his old films, and signed a distribution deal with Moses "Mo" Rothman.[284] In order to promote the re-releases, Chaplin travelled to the US in 1972 for the first time in twenty years to receive a lifetime achievement award from the Lincoln Center Film Society and an Academy Honorary Award for "the incalculable effect he has had in making motion pictures the art form of this century".[285][286] The visit attracted a large amount of press coverage, and at the Academy Awards gala, Chaplin was given a twelve-minute standing ovation, the longest in the Academy's history.[287][288] The following year, he received the Academy Award for Best Original Score for Limelight, the only competitive Academy Award he won during his career.[289]

Although Chaplin still had plans for future film projects, he was by now very frail.[290] In the mid-1970s he experienced several strokes, which made it difficult for him to communicate.[281][291] He also showed signs of dementia, and had to use a wheelchair.[281][291] His final projects were compiling a pictorial autobiography, My Life in Pictures (1974) and rescoring A Woman of Paris for re-release in 1976.[292] He also appeared in a documentary of him, The Gentleman Tramp (1975), directed by Richard Patterson.[293] In 1975, two years before his death, Queen Elizabeth II made him a Knight Commander of the British Empire (KBE).[292]

Death

Chaplin died in his sleep from the complications of a stroke in the early morning of 25 December 1977 at his home in Switzerland.[281][291] The funeral, held two days later on 27 December, was a small and private Anglican ceremony, according to his wishes.[281] He was interred in the Vevey cemetery.

On 1 March 1978, Chaplin's coffin was dug up and stolen from its grave by two unemployed mechanics, Polish Roman Wardas and Bulgarian Gantcho Ganev, in an attempt to extort money from Chaplin's widow, Oona Chaplin.[281] After she refused to pay the ransom, they started to threaten Chaplin's youngest children with violence.[281] Ganev and Wardas were caught in a large police operation in May, and Chaplin's coffin was found buried in a field in the nearby village of Noville.[281] It was reburied three months after it had been stolen[294] in the Vevey cemetery under 6 feet (1.8 m) of reinforced concrete. In December 1978, Wardas received a sentence of four and a half years' imprisonment and Gantcho a suspended sentence for disturbing the peace of the dead and for the attempt of extortion.[281]

Filmmaking

Influences

Chaplin believed his first influence to be his mother, who would entertain him as a child by sitting at the window and mimicking passers-by. "She was one of the greatest pantomime artists I have ever seen," he said, "it was through watching her that I learned not only how to express emotions with my hands and face, but also how to observe and study people."[295] Chaplin's early years in music hall allowed him to see stage comedians at work; he also attended the Christmas pantomimes at Drury Lane, London where he studied the art of clowning.[296] Chaplin's years with the Fred Karno company had a formative effect on him as an actor and filmmaker; Simon Louvish writes that the company was his "training ground".[297] The concept of mixing pathos with comedy was likely learnt from Karno; Stan Laurel, Chaplin's co-performer at the company, remembered that Karno's sketches regularly inserted "a bit of sentiment right in the middle of a funny music hall turn." The impresario also taught his comedians to vary the pace of their comedy, that a hectic speed was not necessary, and used elements of absurdity that would become familiar in Chaplin gags.[298][299] For his film A Night in the Show (1915), Chaplin directly transferred the Karno sketch Mumming Birds onto the screen.[300] From the film industry, Chaplin drew upon the work of French comedian Max Linder, whose films he greatly admired.[301] In developing the Tramp costume and persona, he was likely inspired by the American vaudeville scene, where tramp characters were common.[302]

Method

Chaplin never spoke more than cursorily about his filmmaking methods, claiming such a thing would be tantamount to a magician spoiling his own illusion. After his death, film historians Kevin Brownlow and David Gill examined out-takes from the Mutual films and presented their findings in a three-part documentary Unknown Chaplin (1983).[303][304] According to Brownlow and Gill, Chaplin developed a unique method of filmmaking after achieving independence to direct his own films. Until he began making spoken dialogue films with The Great Dictator (1940), he never shot from a completed script, but instead usually started with only a vague premise —for example "Charlie enters a health spa" or "Charlie works in a pawn shop."[303] He then had sets constructed and worked with his stock company to improvise gags and "business" around them, almost always working the ideas out on film.[303] As ideas were accepted and discarded, a narrative structure would emerge, frequently requiring Chaplin to reshoot an already-completed scene that might have otherwise contradicted the story.[303] Due to the lack of a script, all of his silent films were usually shot in sequence.[305]

This is one reason why Chaplin took so much longer to complete his films than most other filmmakers at the time. If he felt out of ideas on what to do with the story, he would often take a break from the shoot that could last for days, while keeping the studio ready for when he felt inspired again.[306] In addition, Chaplin was an incredibly exacting director, showing his actors exactly how he wanted them to perform[307] and shooting scores of takes until he had the shot he wanted. Animator Chuck Jones, who lived near his Lone Star studio as a boy, remembered his father saying he watched Chaplin shoot a scene more than a hundred times until he was satisfied with it.[308] The ratio between shot footage and footage forming the final edited film would often be high, for example 53 takes per a finished take in The Kid.[309] This combination of story improvisation and relentless perfectionism—which resulted in days of effort and thousands of feet of film being wasted, all at enormous expense—often proved very taxing for Chaplin, who in frustration would often lash out at his actors and crew, keep them waiting idly for hours or, in extreme cases, shutting down production altogether.[310]

Due to his complete independence as a filmmaker, Chaplin has been identified by Andrew Sarris as one of the first auteur filmmakers.[311] However, he also often relied on help from his closest collaborators, such as his long-time cinematographer Roland Totheroh, brother Sydney Chaplin and various assistant directors, such as Harry Crocker and Charles Reisner.[312]

Style and themes

Instead of a tightly unified storyline, Gerald Mast has seen Chaplin's films as consisting of sketches tied together by the same theme and setting.[313] Although most of Chaplin's films are characterised as comedies, most of them also employ strong elements of drama and even tragedy. Chaplin could be inspired by tragic events when creating his films, as in the case of The Gold Rush (1925), which was inspired by the fate of the Donner Party.[314] Some scholars, such as Constance B. Kuriyama, have also identified more serious underlying themes, such as greed (The Gold Rush) or loss (The Kid), in Chaplin's comedies.[315]

"It is paradoxical that tragedy stimulates the spirit of ridicule...ridicule, I suppose, is an attitude of defiance; we must laugh in the face of our helplessness against the forces of nature – or go insane."[316]

—Chaplin on comedy and tragedy in The Gold Rush

Chaplin's silent films usually follow the Tramp's struggles to survive in an often hostile world. According to David Robinson, unlike in more conventional slapstick comedies, the comic moments in Chaplin's films centred on the Tramp's attitude to the things happening to him: the humour did not come from the Tramp bumping into a tree but from his lifting of his hat to the tree in apology.[73] Chaplin also diverged from conventional slapstick by slowing down his pace and exhausting each scene of its comic potential, and focusing more on developing the viewer's relationship to the characters.[73][317] He also often employed inanimate objects in his films, often transforming them into other objects in an almost surreal way, such as in The Pawnshop (1916) and One A.M. (1916), where Chaplin is the only actor aside Chester Conklin's brief appearance in the very first scene.[317]

Chaplin disliked unconventional camera angles and only used close-ups to highlight an emotional scene, and usually preferred to employ a static, "stage-like" camera setting where the scenes were portrayed as if set on a stage.[317][318] To some scholars, such as Donald McCaffrey, this is an indication that Chaplin never completely understood film as a medium,[319] but Gerald Mast has argued that by deliberately adopting this approach, Chaplin made "all consciousness of the cinematic medium disappear so completely that we concentrate solely on the photographic subject rather than the process".[317] Both Richard Schickel and Andrew Sarris have also written that many of the gags in his silent films needed the "intimacy of the camera" to work and could not have been performed on the stage to the same effect.[320][321]

Chaplin portrayed social outcasts and the poor in a sympathetic light in his films from early on. His silent films usually centred on the Tramp's plight in poverty and his run-ins with the law, but also explored controversial topics, such as immigration (The Immigrant, 1917), illegitimacy (The Kid, 1921) and drug use (Easy Street, 1917).[317] Although this can be seen as social commentary, Chaplin's films did not contain overt political themes or messages until later on his career in the 1930s. Modern Times (1936), which depicted factory workers in dismal conditions, was the first of his films that was seen by critics to contain an anti-capitalist message, although Chaplin denied the film being in any way political. However, his next films, The Great Dictator (1940), a parody on Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini that ended in a dramatic speech criticising the blind following patriotic nationalism, and Monsieur Verdoux (1947), which criticised war and capitalism, as well as his first European film A King in New York (1957), which ridiculed the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee, were more clearly political and caused controversy.

Partly due to Chaplin's complete control over the production of his films, Stephen M. Weissman has also seen them as containing autobiographical elements. This was already noted by Chaplin's contemporaries, such as Sigmund Freud, who thought that Chaplin "always plays only himself as he was in his dismal youth",[322] and by some of his collaborators, such as actress Claire Bloom, who starred in Limelight. For example The Kid is thought to reflect Chaplin's own childhood trauma of being sent into an orphanage and the main characters in Limelight (1952) are thought to contain elements from the lives of his parents.[322][323] Many of his sets, especially in street scenes, bear a strong similarity to Kennington, where he grew up. Weissman has also argued that Chaplin's problematic relationship to his mentally ill mother was often reflected on the female characters in his films and the Tramp's desire to save them.[322]

Music

Alongside acting, directing, writing, producing, and editing, Chaplin also composed the musical scores for his films. He developed a passion for music as a child, and taught himself to play the piano, violin, and cello.[324] After achieving fame, he founded a short-lived music company, the Charles Chaplin Music Corporation, through which he published some of his own compositions, such as "Oh, That Cello!" and "Peace Patrol" in 1916. He published two more of his compositions in 1925.[325] Chaplin considered the musical accompaniment of a film to be important,[175] and from A Woman of Paris onwards, he took an increasing interest in this area.[326][327] With the advent of sound technology, Chaplin immediately adopted the use of a synchronised soundtrack—composed by himself—for City Lights (1931).[326][327] He thereafter composed the score for all of his films, and from the late 1950s to his death, he re-scored all of his silent features and some of his short films.[327]

Because Chaplin was not a trained musician, he could not read notes and needed the help of professional composers, such as David Raksin, Raymond Rasch and Eric James, when creating his scores. Although some of Chaplin's critics have claimed that credit for his film music should be given to the composers who worked with him, for example Raksin, who worked with Chaplin on Modern Times, has stressed Chaplin's creative position and active participation in the composing process.[328] This process, which could take months, would start with Chaplin describing to the composer(s) exactly what he wanted and singing or playing a tune he had come up with on the piano.[328] These tunes were then developed further in a close collaboration between the composer(s) and Chaplin.[328] According to film historian Jeffrey Vance, "although he relied upon associates to arrange varied and complex instrumentation, the musical imperative is his, and not a note in a Chaplin musical score was placed there without his assent."[327]

Chaplin's compositions produced two popular songs. "Smile", composed originally for Modern Times (1936) and later set to lyrics by John Turner and Geoffrey Parsons, was a hit for Nat King Cole in 1954.[327] "This Is My Song", performed by Petula Clark for A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), reached #1 on the UK Charts.[329] Chaplin also received his only competitive Oscar for his composition work, receiving the Academy Award for Best Original Score for Limelight (along with Raymond Rasch and Larry Russell) in 1973.[327]

Legacy

Chaplin was one of the first international film stars[330][331] and one of the most famous men of the twentieth century,[332] whose most recognised character, the Tramp, is considered to be cinema's "most universal icon".[331][333] Film critic Leonard Maltin has written that "For me, comedy begins with Charlie Chaplin. I know there were screen comedies before he came along [...] But none of them created a persona as unique or indelible as the Little Tramp, and no one could match his worldwide impact."[334] Chaplin is included in Variety's list of "100 Icons of the Century",[335] in VH1’s list of "The 200 Greatest Pop Culture Icons",[336] in TIME's list of the "100 Most Important People of the 20th Century",[337] and was voted 10th most important male star of all time by the American Film Institute.[5] In 2002, he was also ranked number 66 on a list of the 100 Greatest Britons, broadcast on the BBC.[338] Memorabilia connected to Chaplin still fetches large sums in auctions: in 2006 a bowler hat and a bamboo cane that he used while in the role of the Tramp were bought with a record sum of $140,000 in a Los Angeles auction.[339]

In addition to being one of cinema's most iconic stars, Chaplin was one of the medium's first artists[340][341] and one of the most influential filmmakers of the first four decades of the twentieth century.[342] Mark Cousins has written that Chaplin "changed not only the imagery of cinema, but also its sociology and grammar" and considers Chaplin to have been as important to the development of comedy as a genre as D.W. Griffith was to drama.[343] He was the first to popularise feature-length comedy and to slow down the pace of action, adding pathos and subtlety to it.[344] Although his comedies are mostly classified as slapstick, Chaplin's only drama film, A Woman of Paris (1923) was a major influence for Ernst Lubitsch's film The Marriage Circle (1924) and hence also played an important part in the development of the genre of sophisticated comedy.[345][346]However, since the 1970s, Chaplin's reputation as a filmmaker has slightly diminished with the advent of the formalist film theory, which concentrates on the technical aspects of film and has tended to stress the historical importance of Buster Keaton as opposed to Chaplin.[347]

Chaplin not only influenced filmmakers, but also artists and entertainers in other fields: he inspired both pop culture (for example comics and cartoon characters, such as Felix the Cat[348] and Mickey Mouse[349]) and high art (for example the Dada movement[350]). As one of the founding members of United Artists, Chaplin also had a role in the development of the film industry. Gerald Mast has written that although UA never became a major company like MGM or Paramount Pictures, the idea that filmmakers could themselves produce their own films was "years ahead of its time".[351]

Memorials and tributes

Several memorials have been dedicated to Chaplin. In London, a statue of him as the Tramp was unveiled in Leicester Square in 1981 and a permanent exhibition on his life and career, Charlie Chaplin – The Great Londoner, opened at the London Film Museum in 2010.[352] The Swiss town of Vevey, where he was a resident during his final years, named a park in his honour in 1980 and erected a replica of the Doubleday statue there in 1982.[353] In 2011 two murals depicting Chaplin on two 14-storey buildings were also unveiled in Vevey.[354] His final home in the area, Manoir de Ban, is in the process of being converted into a museum exploring his life and career, to be opened in 2014.[355] Chaplin's photographic archives are held by the Musée de l'Élysée in Lausanne, and some of the images in the collection were presented in an exhibition, Charlie Chaplin – Images d'Un Mythe, in 2011–2012.[356] In 1998, Chaplin also received a statue in Waterville, Ireland, where he spent several summers with his family in the 1960s.[357] Since 2011 the town has also been host to the annual Charlie Chaplin Comedy Film Festival, which was founded to celebrate Chaplin's legacy and to showcase new comic talent.[358]

Chaplin's 100th birthday anniversary in 1989 was celebrated with several events. On his birthday, 16 April, City Lights was screened at a gala at the Dominion Theatre in London, the site of its British premiere in 1931.[359] In Hollywood, a screening of a restored version of How to Make Movies was held at his former studio, and in Japan, he was honoured with a musical tribute.[360] Retrospectives of his work were presented that year at The National Film Theatre in London,[360] the Munich Stadtmuseum[360] and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which also dedicated a gallery exhibition, Chaplin: A Centennial Celebration, to him.[361] On 15 April 2011, a day before his 122nd birthday anniversary, Google celebrated him with a special Google Doodle video on its global and other country-wide homepages.[362]

Chaplin has also been remembered in several other ways. A minor planet, 3623 Chaplin, discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Karachkina in 1981, is named after him.[363] In 1985, he was honoured with his image on a postage stamp of the United Kingdom along with Alfred Hitchcock, Vivien Leigh, Peter Sellers and David Niven to commemorate "British Film Year".[364] In 1994 he appeared on a United States postage stamp designed by caricaturist Al Hirschfeld. In 2010 the New York Guitar Festival commissioned new scores on some of Chaplin's silent films from a number of contemporary artists, including Justin Vernon of Bon Iver, Marc Ribot, David Bromberg, and Alex de Grassi.[365] In 1964 Chaplin wrote an autobiography, My Autobiography.

Characterizations

Chaplin has been portrayed in several films. Richard Attenborough directed a film on Chaplin's life, Chaplin (1992), which starred Robert Downey, Jr. as Chaplin and also included Chaplin's oldest daughter Geraldine Chaplin playing his mother, Hannah Chaplin. Downey Jr. was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor and won a BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role for his performance.[366] Chaplin is also a supporting character in several other films, such as The Cat's Meow (2001), in which he was played by Eddie Izzard and The Scarlett O'Hara War (1980), in which he was played by Clive Revill.

Chaplin has also been the subject of a musical, Limelight: The Story of Charlie Chaplin, by Christopher Curtis and Thomas Meehan, which was performed at the La Jolla Playhouse in 2010.[367] It was adapted for Broadway in 2012, retitled Chaplin – A Musical.[368] Chaplin is portrayed by Robert McClure in both.

Chaplin is also one of the central characters in Glen David Gold's novel Sunnyside, which is set in the World War I period.[369]

Awards and recognition

Chaplin received several awards and recognitions during his lifetime, especially during his later career in the 1960s and the 1970s. In 1975, he was knighted a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by Queen Elizabeth II.[370][371] The honour had already been proposed in 1931 and 1956, but was vetoed after a Foreign Office report raised concerns over Chaplin's political views and private life; it was felt that honouring him would damage both the reputation of the British honours system and relations with the United States.[372] Chaplin was also awarded honorary Doctor of Letters degrees by the University of Oxford and the University of Durham in 1962.[373] In 1965 he received a joint Erasmus Prize with film director Ingmar Bergman [374] and in 1971 he was made a Commander of the national order of the Legion of Honor at the Cannes Film Festival in France.[375]

Chaplin also received several special film awards. He was given a special Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1972.[376] When he briefly returned to the United States in 1972, the Lincoln Center Film Society honoured him with a gala and awarded him a lifetime achievement award, which has since been awarded annually to filmmakers as The Chaplin Award.[377] Chaplin was also given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1970, after having been excluded due to his political beliefs when the project was initially started in 1958.[378]

Chaplin also received three Academy Awards, one competitive award for Best Original Score, and two Honorary Awards, and was nominated for three more:

- 1st Academy Awards (1929): Special Award "for versatility and genius in acting, writing, directing and producing The Circus". Chaplin had originally been nominated for Best Production, Best Director in a Comedy Picture, Best Actor and Best Writing (Original Story) for The Circus. However, the Academy decided to withdraw his name from all the competitive categories and instead give him a special award.[379]

- 13th Academy Awards (1941): Best Actor and Best Writing, nominations, for The Great Dictator. The film was also nominated for further three awards.[380]

- 20th Academy Awards (1948): Best Screenplay, nomination, for Monsieur Verdoux.

- 44th Academy Awards (1972): Honorary Award for "the incalculable effect he [Chaplin] has had in making motion pictures the art form of this century".

- 45th Academy Awards (1973): Best Original Score, win, for Limelight. Although the film had originally been released in 1952, due to Chaplin's political difficulties at the time, it did not play for one week in Los Angeles, and thus did not meet the criterion for nomination until it was re-released in 1972.[289]

Six of Chaplin's films have been selected for preservation in the National Film Registry: The Immigrant (1917), The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1925), City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936), and The Great Dictator (1940).

Filmography

Chaplin appeared in 82 films throughout his 53 years in the industry. Nearly all of his output is owned by Roy Export S.A.S. in Paris, which enforces the library's copyrights and decides how and when this material can be released.

Directed features:

- The Kid (1921)

- A Woman of Paris (1923)

- The Gold Rush (1925)

- The Circus (1928)

- City Lights (1931)

- Modern Times (1936)

- The Great Dictator (1940)

- Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

- Limelight (1952)

- A King in New York (1957)

- A Countess from Hong Kong (1967)

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^ An MI5 investigation in 1952 was unable to find any record of Chaplin's birth.[9] Chaplin biographer David Robinson notes that it is not surprising that his parents failed to register the birth: "It was easy enough, particularly for music hall artists, constantly moving (if they were lucky) from one town to another, to put off and eventually forget this kind of formality; at that time the penalties were not strict or efficiently enforced."[8] In 2011 a letter sent to Chaplin in the 1970s came to light which claimed that he had been born in a Gypsy caravan at Black Patch Park in Smethwick, Staffordshire. Chaplin's son Michael has suggested that the information must have been significant to his father in order for him to retain the letter.[10]

- ^ Sydney was born when Hannah Chaplin was 19; his biological father cannot be known for sure. Hannah Chaplin later told her sons that he was a bookmaker named Hawkes, but this cannot be verified. Sydney's birth certificate and baptismal records omit the name of the father.[12]

- ^ In the years Chaplin was touring with The Eight Lancashire Lads, his mother ensured that he still attended school.[39]

- ^ William Gillette co-wrote the Sherlock Holmes play with Arthur Conan Doyle, and had been starring in it since its New York opening in 1899. He had come to London in 1905 to appear in a new play, Clarice. Its reception was poor, and Gillette decided to add an "after-piece" called The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes. This short play was what Chaplin originally came to London to appear in. After three nights, however, Gillette chose to close Clarice and replace it with Sherlock Holmes. Chaplin had so pleased Gillette with his performance in The Painful Predicament that he was kept on as Billy for the full play.[45]

- ^ £3 10s was a considerable amount in 1908. Using the Retail Price Index, in 2012 this would be equivalent to a salary of £285 a week. Based on average earnings at that time, however, it held an "economic power" equivalent to £2,540.[55]

- ^ In July 1915, Chaplin had agreed to produce ten two-reel films for Essanay by the start of 1916. He completed only six films in this period, leading the court to conclude that extending Burlesque on Carmen to four reels was justified.

- ^ Chaplin first confirmed their marital status in 1940, at the première of The Great Dictator, when he referred to Goddard as "my wife".[220]

- ^ Chaplin later said that if he had known the extent of the Nazi Party's actions he would not have made the film; "Had I known the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator; I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis."[227]

- ^ Speculation about Chaplin's racial origin existed from the earliest days of his fame, and it was often reported that he was a Jew. Research has uncovered no evidence of this, however, and when a reporter asked in 1915 if it was true, Chaplin responded, "I have not that good fortune." The Nazi Party believed that he was Jewish, and banned The Gold Rush on this basis. Chaplin responded by playing a Jew in The Great Dictator and announced, "I did this film for the Jews of the world." He thereafter refused to deny claims that he was Jewish, saying, "Anyone who denies this aspect of himself plays into the hands of the anti-Semites."[232]

- References

- ^ Obituary Variety Obituaries, 28 December 1977.

- ^ Blanke, David (2002). The 1910s. American popular culture through history (illustrated ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-313-31251-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Haupert, Michael (2006). The Entertainment Industry. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-313-32173-3.

- ^ Kelly, Shawna (2008). Aviators in Early Hollywood (illustrated ed.). Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7385-5902-5.