Operation Overlord

| Operation Overlord | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Western Front of World War II | |||||||

Tank landing ships unloading supplies on Omaha Beach, building up for the breakout from Normandy. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Western Allies

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

(Supreme Allied Commander) (Deputy Supreme Allied Commander) (Ground Forces Commander in Chief) (Air Commander in Chief) (Naval Commander in Chief) |

(Oberbefehlshaber West) (Heeresgruppe B) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,452,000 (by 25 July)[nb 1] 2,052,299 (by 21 August, in northern France alone)[nb 2] |

380,000 (by 23 July)[nb 3] – 1,000,000+[nb 4] 2,200[3] – ~2,300 tanks and assault guns[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

226,386 casualties[nb 5]

[nb 6] |

209,875[nb 8] – 450,000 casualties[nb 9]

2,127 planes[8] | ||||||

|

Civilian Deaths 11,000-19,000 killed in pre-invasion bombing [9] 13,632–19,890 killed during invasion[9] Total: 25,000-39,000 killed | |||||||

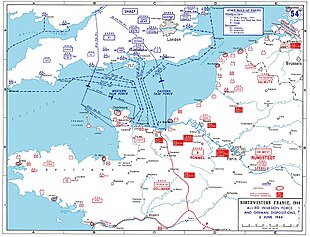

Operation Overlord[10] was the code name for the Battle of Normandy, the operation that launched the invasion of German-occupied western Europe during World War II by Allied forces. The operation commenced on 6 June 1944 with the Normandy landings (Operation Neptune, commonly known as D-Day). A 12,000-plane airborne assault preceded an amphibious assault involving almost 7,000 vessels. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel on 6 June; more than three million allied troops were in France by the end of August.[11]

Allied land forces that saw combat in Normandy on D-Day itself came from the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. Free French Forces and Poland also participated in the battle after the assault phase, and there were also minor contingents from Belgium, Greece, the Netherlands, and Norway.[12] Other Allied nations participated in the naval and air forces.

The battle for Normandy continued for more than two months, concluding with the closing of the Falaise pocket on 24 August, the Liberation of Paris on 25 August, and the German retreat across the Seine which was completed on 30 August 1944.[13]

Preparations for D-Day

In June 1940, German dictator Adolf Hitler had triumphed in what he called "the most famous victory in history" – the fall of France.[14] Britain, although besieged, evacuated 300,000 troops from Dunkirk. The British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, in one of his famous speeches, vowed to invade France and liberate it from Nazi Germany (![]() Quotations related to God Protect France at Wikiquote).

Quotations related to God Protect France at Wikiquote).

In a joint statement with the Soviet premier Communist Party General Secretary Joseph Stalin and the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Churchill announced in 1942 a "full understanding" concerning the urgent task of creating a second front in Europe. Churchill unofficially informed the Soviets in a memorandum handed to Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov that the resources necessary for an invasion were lacking in 1942.[15] However, the announcement had some effect as it caused Hitler to order preparations for an Allied descent on Europe.[16]

The British, under Churchill, wished to avoid the costly frontal assaults of World War I - Churchill's previous experience of opening a second front via an invasion had been the disastrous campaign in Gallipoli, Turkey. Churchill and the British staff favoured a course of allowing the insurgency work of the Special Operations Executive to come to widespread fruition, while making a main Allied thrust from the Mediterranean Sea to Vienna and into Germany from the south, concentrating on the weaker Axis ally, Italy. Such an approach was also believed to offer the advantage of creating a barrier to limit the Soviet advance into Europe. However, the U.S. government believed from the onset that the optimum approach was the shortest route to Germany emanating from the strongest Allied power base: Great Britain. They were adamant in their view and made it clear that it was the only option they would support in the long term. Two preliminary proposals were drawn up: Operation Sledgehammer, for an invasion in 1942, and Operation Roundup, for a larger attack in 1943, which was adopted and became Operation Overlord, although it was delayed until 1944.[17]

This operation will be the primary United States and British ground and air effort against the Axis of Europe. Following the establishment of strong Allied forces in France, operations designed to strike at the heart of Germany and to destroy her military forces will be undertaken. We have approved the outline plan for Operation Overlord.

— Report by Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff, Quebec Conference, August 1943

The planning process was started in earnest after the Casablanca and Tehran Conferences[18] with the appointment of British Lieutenant-General Frederick E. Morgan[19] as Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (Designate), a title shortened to COSSAC, with the American Major General Ray Barker as his deputy. The COSSAC staff's initial plans were constrained by the numbers of landing craft available, which were reduced by commitments in the Mediterranean and Pacific.[20] In part because of lessons learned by Allied troops in the raid on Dieppe of 19 August 1942, the Allies decided not to assault a French seaport directly in their first landings.[21] The short operating range of British fighters, including the Spitfire and Typhoon, from UK airfields greatly limited the number of potential landing sites, as comprehensive air support depended upon having planes overhead for as long as possible.[18] Geography reduced the choices further to two sites: the Pas de Calais and the Normandy coast.[22]

Normandy presented serious logistical and operational problems. Logistical problems were presented by the fact that the only viable port in the area, Cherbourg, was heavily defended. Many among the higher echelons of command argued that the Pas de Calais would make a more suitable landing area on these grounds alone. Second, the Calais area is north of the Seine river, but Normandy is on the south ('wrong') side, constraining operations.

Because the Pas de Calais was the shortest distance to Germany from Britain,[23] it was the most heavily fortified region. It was also considered that it offered few opportunities for expansion as the area was bounded by numerous rivers and canals,[24] whereas landings on a broad front in Normandy would permit simultaneous threats against the port of Cherbourg, coastal ports further west in Brittany, and an overland attack towards Paris and towards the border with Germany. Normandy was a less-defended coast and an unexpected but strategic jumping-off point, with the potential to confuse and scatter the German defending forces.[22] Normandy was hence chosen as the landing site.[25]

The COSSAC staff planned to launch the invasion on 1 May 1944.[24] The initial draft of the COSSAC plan was accepted at the Quebec Conference in August 1943, but no supreme commander was appointed for several months. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) in November 1943.[26] SHAEF was based in Camp Griffiss, Bushy Park, Teddington, south-west London, and had over 1200 military personnel. General Bernard Montgomery was named as commander of the 21st Army Group, to which all of the invasion ground forces belonged, and was also given charge of developing the invasion plan.[27] Both Eisenhower and Montgomery first saw the COSSAC plan on 31 December 1943 at Marrakech in Morocco, in a conference with Winston Churchill. They insisted immediately that the scale of the initial invasion be expanded, to prevent the invaders being restricted to a narrow beachhead, with insufficient room to land follow-up formations and vulnerable to German counter-attacks.[28] The need to acquire or produce extra landing craft for this expanded operation meant that the invasion had to be delayed to June.

The COSSAC plan proposed a landing from the sea by three divisions, with two brigades landed by air. Following Eisenhower's and Montgomery's revision of the plan, this was expanded to landings by five divisions and airborne descents by three divisions. In total, 39 Allied divisions would be committed to the Battle of Normandy: 22 US, 12 British, three Canadian, one Polish and one French, all under overall British command [29][nb 11], totalling over a million troops.[32]

Detail planning

In preparation, the BBC appealed for holiday pictures and snaps of France for an exhibition. Those of the Normandy beaches were singled out to create detailed geological maps of the area. What was already known of the make-up was that the targeted beaches were underpinned in places by ancient woodland, which had created peat bogs not far below the surface of the beaches. Tests on similar beaches in Norfolk in 1943 proved them unsuitable for taking the weight of heavy tanks and transport, so detailed maps of the area were required. In December 1943, Operation Postage Able used an X-craft to collect suitable data for all of the beaches. Where the areas of peat could not be avoided, they were to be covered with rolls of matting deployed from spools nicknamed "bobbins" (or more prosaically, "bog rolls") mounted on modified tanks.[33]

On 7 April and 15 May, Montgomery presented his strategy for the invasion at St Paul's School.[34] He envisaged a ninety day battle, ending when all the forces reached the Seine,[35] pivoting on an Allied-held Caen,[nb 12] with British and Canadian armies forming a shoulder and the U.S. armies wheeling to the right

The objective for the first 40 days was to create a lodgement that would include the cities of Caen and Cherbourg (especially Cherbourg, for its deep-water port). Subsequently, there would be a breakout from the lodgement to liberate Brittany and its Atlantic ports, and to advance to a line roughly 125 miles (190 km) to the southwest of Paris, from Le Havre through Le Mans to Tours, so that after ninety days the Allies would control a zone bounded by the rivers Loire in the south and Seine in the northeast.

Technology

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2009) |

The Allies developed new technologies for Overlord. The "mulberry", a mobile, prefabricated concrete harbor, allowed the Allies to supply their beachhead without capturing one of the heavily defended Channel ports, as did the Pipe-Line Under The Ocean (PLUTO).[37] Major-General Percy Hobart, an unconventional military engineer, assembled a force of modified Sherman and Churchill tanks known as Hobart's Funnies, which were used at Normandy.

Deception

In the months leading up to the invasion, the Allies conducted a deception operation, Operation Bodyguard, designed to persuade the Germans that areas other than northern France would be threatened as well (such as the Balkans and the south of France). Then, in the weeks leading up to the invasion, in order to persuade the Germans that the main invasion would really take place at the Pas de Calais and to lead them to expect an invasion of Norway, the Allies prepared a massive deception plan, called Operation Fortitude. Operation Fortitude North would lead the Axis to expect an attack on Norway; the much more vital Operation Fortitude South was designed to lead the Germans to expect the main invasion at the Pas de Calais and to hold back forces to guard against this threat rather than rushing them to Normandy.[38]

An entirely fictitious First U.S. Army Group ("FUSAG"), supposedly located in southeastern Britain under the command of General Lesley J. McNair and Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., was created in German minds by the use of double agents and fake radio traffic. The Germans had an extensive network of agents operating in the UK, all of whom had been "turned" by the Allies as part of the Double Cross System and were sending back messages "confirming" the existence and location of FUSAG and the Pas de Calais as the likely main attack point.[38] Dummy tanks (some inflatable), trucks and landing craft, as well as troop camp facades (constructed from scaffolding and canvas) were placed in ports on the eastern and southeastern coasts of Britain and the Luftwaffe was allowed to photograph them. During this period, most of the Allied naval bombardment was focused on Pas de Calais instead of Normandy. The Allied Forces even went as far as to broadcast static over Axis radio frequencies and convinced Germany to expend efforts to try to decode white noise, further leading Germany away from the Normandy invasion.

In aid of Operation Fortitude North, Operation Skye was mounted from Scotland using radio traffic, designed to convince German traffic analysts that an invasion would also be mounted into Norway. Against this phantom threat, German units that could have been moved into France were kept in Norway.

Operation Cover (2–5 June) Eighth Air Force Missions 384, 388, 389 & 392 bombed transportation and airfield targets in Northern France and "coastal defenses, mainly located in the Pas de Calais coastal area, to deceive the enemy as to the sector to be invaded".[39]

The last part of the deception occurred on the night before the invasion: a small group of SAS operators deployed dummy paratroopers over Le Havre and Isigny. These dummies led the Germans to believe that an additional airborne assault had occurred; this diverted reinforcing troops and kept the true situation unclear. On that same night, two RAF squadrons (No. 617 Squadron and No. 218 Squadron) in Operation Taxable and Operation Glimmer created an illusion of a massive naval convoy sailing for the Cap d'Antifer (15 miles north of Le Havre). This was achieved by the precision dropping of "Window", strips of metal foil. The foil caused a radar return mistakenly interpreted by German radar operators as a fleet of small craft towing barrage balloons.[40]

Rehearsals and security

Allied forces rehearsed their roles for D-Day months before the invasion. On 28 April 1944, in south Devon on the British coast, 946 American soldiers and sailors were killed when German torpedo boats surprised one of these landing exercises, Exercise Tiger.[41]

The effectiveness of the deception operations was increased by a news blackout from Britain. Travel to and from the Republic of Ireland was banned, and movements within several miles of the coasts restricted.[42] The German embassies and consulates in neutral countries were flooded with all sorts of misleading information, in the well-founded hope that any genuine information on the landings would be ignored with all the confusing chaff.

There were several leaks prior to or on D-Day. Through the Cicero affair, the Germans obtained documents containing references to Overlord, but these documents lacked all detail.[43] Another such leak was General Charles de Gaulle's radio message after D-Day. He, unlike all the other leaders, stated that this invasion was the real invasion.[nb 13] This had the potential to ruin the Allied deceptions Fortitude North and Fortitude South. For example, Eisenhower referred to the landings as the initial invasion. Nevertheless, the Germans did not believe de Gaulle and waited too long to move in extra units against the Allies.

Allied invasion plan

The British were to take an airborne assault on the River Orne. The British objective was to secure the Orne River bridges; first to prevent German armor from using them to cross the river and disrupt the landings; second to hold them against destruction by the retreating Germans so that they could be used by Allied armor and logistics as the invasion moved inland. The British amphibious assault units would attack through Sword and Gold Beaches. The United States had an airborne division and land units, which were to take Omaha Beach, the Pointe du Hoc and Utah Beach. The Canadians would team up with British units to attack Sword Beach. The British and Canadians had separate beaches, Gold Beach and Juno Beach, respectively.

The Invasion Fleet was drawn from eight navies made up of warships and submarines, split into the Western Naval Task Force (Rear-Admiral Alan G Kirk) and the Eastern Naval Task Force (Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian). The fleet was overall led by Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay.

Codenames

The Allies assigned codenames to the various operations involved in the invasion. Overlord was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale lodgement on the Continent. The first phase, the establishment of a secure foothold, was codenamed Neptune.[45] It began on D-Day (6 June 1944) and ended on 30 June 1944. By this time, the Allies had established a firm foothold in Normandy. Operation Overlord also began on D-Day, and continued until Allied forces crossed the river Seine on 19 August 1944.

German preparations and defenses

Atlantic Wall

Through most of 1942 and 1943, the Germans had rightly regarded the possibility of a successful Allied invasion in the west as remote. Preparations to counter an invasion were limited to the construction, by the Organisation Todt, of impressive fortifications covering the major ports. The number of military forces at the disposal of Nazi Germany reached its peak during 1944 with 59 divisions stationed in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.[46]

In late 1943, the obvious Allied buildup in Britain prompted the German Commander-in-Chief in the west, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, to request reinforcements. In addition to fresh units, von Rundstedt also received a new subordinate, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. Rommel originally intended only to make a tour of inspection of the Atlantic Wall. After reporting to Hitler, Rommel requested command of the defenders of northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands. These were organised as Army Group B in February 1944. (The German forces in southern France were designated as Army Group G, under General Johannes Blaskowitz).

Rommel had recognized that for all their propaganda value, the Atlantic Wall fortifications covered only the ports themselves. The beaches between were barely defended, and the Allies could land there and capture the ports from inland. He revitalised the defenders, who laboured to improve the defences of the entire coastline. Steel obstacles were laid at the high-water mark on the beaches, concrete bunkers and pillboxes constructed, and low-lying areas flooded. Given the Allied air supremacy (12,000 Allied aircraft against 300 Luftwaffe fighters[47]), booby-trapped stakes known as Rommelspargel (Rommel's asparagus) were set up on likely landing grounds to deter airborne landings.

These works were not fully completed, especially in the vital Normandy sector, partly because Allied bombing of the French railway system interfered with the movement of the necessary materials, and also because the Germans were convinced by the Allied deception measures and their own preconceptions that the landings would take place in the Pas de Calais, and so they concentrated their efforts there.

The Germans had nevertheless extensively fortified the foreshore area as part of their Atlantic Wall defences (including sunken tank turrets and extensive barbed wire), believing that any forthcoming landings would be timed for high tide (this caused the landings to be timed for low tide). The sector which was attacked was guarded by four divisions, of which the 352nd and 91st were of high quality. The other defending troops included Germans who were not considered fit for active duty on the Eastern Front (usually for medical reasons) and various other nationalities such as conscripted Poles and former Soviet prisoners-of-war who had agreed to fight for the Germans rather than endure the harsh conditions of German POW camps. These "Ost" units were provided with German leadership to manage them.

Mobile reserves

Rommel's defensive measures were also frustrated by a dispute over armoured doctrine. In addition to his two army groups, von Rundstedt also commanded the headquarters of Panzer Group West under General Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg (usually referred to as von Geyr) to administer the mobile formations in reserve. Von Geyr and Rommel disagreed over the deployment and use of the vital Panzer divisions.

Rommel proposed that the armoured formations be deployed close to the coast, to counter-attack while the invaders were vulnerable. Von Geyr argued that they should instead be concentrated in a central position around Paris and deployed en masse against the main Allied beachhead when this had been identified. When the matter was brought before Hitler, he imposed an unworkable compromise solution. Rommel was given only three tank divisions, only one of which was stationed close enough to the Normandy beaches to intervene on the first day. The other mechanized divisions capable of intervening in Normandy were retained under the direct control of the German Armed Forces HQ (OKW) and were scattered across France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Weather forecast

The opportunity for launching an invasion was limited to only a few days in each month as a full moon was required, for light for the aircraft pilots and for the spring tide. Eisenhower had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault. However, on 4 June, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing; high winds and heavy seas made it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft finding their targets. The Germans meanwhile took comfort from the existing poor conditions and believed an invasion would not be possible for several days. Some troops stood down, and many senior officers were absent. Rommel, for example, took leave to attend his wife's birthday.

Since April, the Captain-class frigate HMS Grindall had been transmitting weather reports from the mid-Atlantic every three hours. From these reports, Group Captain James Stagg RAF, Eisenhower's chief meteorologist, predicted a slight improvement in the weather for 6 June. Grindall's reports indicated a ridge of high pressure behind a deep depression. Stagg forecast that the ridge would move eastward to reach the south-west approaches to the Channel late on 5 June, bringing a short improvement in the weather.

At a vital meeting late on 5 June, Eisenhower and his senior commanders discussed the situation. General Montgomery and Major General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower's chief of staff, were eager to launch the invasion. Admiral Bertram Ramsay also was prepared to commit his ships, while Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory was concerned that the conditions would be unfavourable for Allied aircraft to operate. After much discussion, Eisenhower decided to launch the invasion that night.[48]

Had Eisenhower postponed the invasion, the only option was to go two weeks later but this would have encountered the 'worst channel storm in 40 years' as Churchill later described it, which lasted four days between 19 and 22 June.

The invasion

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

— Eisenhower, Letter to Allied Forces[49]

To eliminate the Germans' ability to organize and launch counterattacks during the amphibious assault phase, airborne operations were used to seize key objectives, such as bridges, road crossings and terrain features, particularly on the eastern and western flanks of the landing areas. The airborne landings some distance behind the beaches were also intended to ease the egress of the amphibious forces off the beaches and in some cases to neutralize German coastal defense batteries and more quickly expand the area of the beachhead. Dropping behind enemy lines hours before the beach landings, the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were assigned to objectives west of Utah Beach. The British 6th Airborne Division was assigned to similar objectives on the eastern flank.[50] 530 Free French paratroopers from the British Special Air Service Brigade, were assigned to objectives in Brittany from 5 June to August.[51][52] (Operation Dingson, Operation Samwest, Operation Cooney).

The beaches

On Sword Beach, the regular British infantry came ashore with light casualties. They had advanced about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) by the end of the day but failed to make some of the deliberately ambitious targets set by Montgomery. In particular, Caen, a major objective, was still in German hands by the end of D-Day and would remain so until Operation Charnwood on 9 July.

The Canadian forces that landed on Juno Beach faced machine-gun nests, pillboxes, other concrete fortifications and a seawall twice the height of the one at Omaha Beach. Juno was the second most heavily defended beach on D-Day, next to Omaha.[citation needed] Despite the obstacles, the Canadians were off the beach within hours and advancing inland with minimal casualties.[53] The Canadians were the only units to wholly reach their D-Day objectives, although most units fell back a few kilometres to stronger defensive positions.

At Gold Beach, the casualties were also quite heavy, because the Germans had strongly fortified a village on the beach. However, the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division overcame these difficulties and advanced almost to the outskirts of Bayeux by the end of the day. The link with commando units securing the Port-en-Bessin gave the Allies a base to deploy their PLUTO pipeline, as an alternative to the experimental 'Tombola', a conventional tanker ship-to-shore storage system.

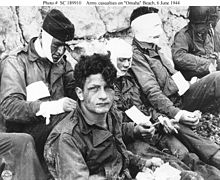

The Americans who landed on Omaha Beach faced the veteran German 352nd Infantry Division, one of the best trained on the beaches. Furthermore, Omaha was the most heavily fortified beach and the majority of landings missed their assigned sectors. Commanders considered abandoning the beachhead but small units of infantry, often forming ad hoc groups, eventually infiltrated the coastal defenses. Further landings were able to exploit the penetrations and by the end of day two footholds had been established. The tenuous beachhead was expanded over the following days and the D-Day objectives were accomplished by D+3.

At Pointe du Hoc, the task for the 2nd Ranger battalion commanded by Lt. Colonel James Rudder, was to scale the 30 metres (98 ft) cliffs under enemy fire and grenades with ropes and ladders and then destroy the guns there. The beach fortifications were vital targets since a single artillery forward observer based there could have directed fire on the U.S. beaches. The Rangers were eventually successful and captured the fortifications. They then had to fight for 2 days to hold the location, losing more than 60 percent of their men.

Casualties on Utah Beach, the westernmost landing zone, were the lightest of any beach, at 197 out of the roughly 23,000 troops that landed. Although the 4th Infantry Division troops that landed on the beach found themselves too far to the southeast, they landed on a lightly defended sector that had relatively little German opposition and the 4th Infantry Division was able to press inland by early afternoon, linking up with the 101st Airborne Division.

Once the beachhead was established, the Mulberry Harbours were made operational around 9 June. One was constructed at Arromanches by British forces, the other at Omaha Beach by American forces. Severe storms on 19 June interrupted the landing of supplies and destroyed the Omaha harbour. The Arromanches harbour was able to supply around 9,000 tons of materiel daily until the end of August 1944, by which time the port of Cherbourg had been secured by the Allies.

Despite this, the German 21st Panzer division mounted a counterattack, between Sword and Juno beaches and succeeded in nearly reaching the channel. Stiff resistance by anti-tank gunners and fear of being cut off caused them to withdraw before the end of 6 June. According to some reports, the sighting of a wave of airborne troops flying over them was instrumental in the decision to retreat.

The Allied invasion plans had called for the capture of Carentan, St. Lô, Caen and Bayeux on the first day, with all the beaches linked except Utah and Sword (the last linked with paratroopers) and a front line 10 to 16 kilometres (6.2 to 9.9 mi) from the beaches; none of these had been achieved. Casualties had not been as heavy as some had feared (around 10,000 compared to the 20,000 Churchill had estimated) and the bridgeheads had withstood the expected counterattacks.

Cherbourg

In the western part of the lodgement, US troops were to occupy the Cotentin Peninsula, especially Cherbourg, which would provide the Allies with a deep water harbour. The country behind Utah and Omaha beaches was characterised by bocage; ancient banks and hedgerows, up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) thick, spread 100 to 200 metres (330 to 660 ft) apart, both seemingly being impervious to tanks, gunfire and vision, thus making ideal defensive positions. The U.S. infantry made slow progress and suffered many casualties as they pressed towards Cherbourg. The airborne troops were called on several times to restart an advance. The far side of the peninsula was reached on 18 June. Hitler prevented German forces from retreating to the strong Atlantic Wall fortifications in Cherbourg and after initially offering stiff resistance, the Cherbourg commander, Lieutenant General von Schlieben, capitulated on 26 June.[54] Before surrendering he had most of the facilities destroyed, making the harbour inoperable until the middle of August, by which time the combat front had moved so far east that it was less helpful.[55]

Caen

Whilst the Americans headed for Cherbourg, a unit of troops led by the British moved towards the city of Caen. Believing Caen to be the "crucible" of the battle, Montgomery made it the target of a series of attritional attacks. The first was Operation Perch, which attempted to push south from Bayeux to Villers-Bocage where the armour could then head towards the Orne and envelop Caen but was halted at the Battle of Villers-Bocage. After a delay owing to the difficulty of supply because of storms from 17 June until 23 June, a German counterattack (which was known through Ultra intelligence) was forestalled by Operation Epsom. Caen was severely bombed and then occupied north of the River Orne in Operation Charnwood from 7 July until 9 July. An offensive in the Caen area followed with all three British armoured divisions, codenamed Operation Goodwood from 18 July until 21 July that captured the high ground south of Caen while the remainder of the city was captured by Canadian forces during Operation Atlantic. A further operation, Operation Spring, from 25 July until 28 July, by the Canadians secured limited gains south of the city at a high cost.

Breakout from the beachhead

An important element of Montgomery's strategy was to cause the Germans to commit their reserves to the eastern part of the theater to allow an easier breakout from the west.[dubious – discuss] By the end of Operation Goodwood, the Germans had committed the last of their reserve divisions; there were six and a half Panzer divisions facing the British and Canadian forces compared to one and a half facing the United States armies. Operation Cobra was launched on 25 July by the U.S. First Army and was extremely successful with the advance guard of VIII Corps entering Coutances at the western end of the Cotentin Peninsula on 28 July, after a penetration through the German lines.

On 1 August, VIII Corps became part of Lieutenant General George S. Patton's newly arrived U.S. Third Army. On 4 August, Montgomery altered the invasion plan by detaching only a corps to occupy Brittany and hem the German troops there into enclaves around the ports, while the rest of the Third Army continued east. The U.S. First Army turned the German front at its western end. Because of the concentration of German forces south of Caen, Montgomery moved the British armor west and launched Operation Bluecoat from 30 July until 7 August to add to the pressure from the United States armies. This drew the German forces to the west, allowing the launch of Operation Totalize south from Caen on 7 August.

Falaise pocket

By the beginning of August, more German reserves became available with the realisation that no landings were going to take place near Calais. The German forces were being encircled and the German High Command wanted these reserves to help an orderly retreat to the Seine. However, they were overruled by Hitler who demanded an attack at Mortain at the western end of the pocket on 7 August. The attack was repelled by the Allies, who again had advance warning from Ultra. The original Allied plan was for a wide encirclement as far as the Loire valley but Bradley realized that many of the German forces in Normandy were not capable of maneuver by this stage and he obtained Montgomery's agreement by telephone on 8 August for a "short hook" further north to encircle German forces. This was left to Patton to effect, moving nearly unopposed through Normandy via Le Mans and then back north again towards Alençon. The Germans were left in a pocket with its jaws near Chambois. Fierce German defense and the diversion of some American troops for a thrust by Patton towards the Seine at Mantes prevented the jaws closing until 21 August, trapping 50,000 German troops. Whether this could have been achieved earlier with more prisoners taken has been a matter of some controversy. Patton's thrust prevented the Germans from establishing the Seine as a defensive line and the Canadian First and British Second Armies both advanced there, bringing the war in Normandy in their sector to a close ahead of the schedule set by Montgomery.

The liberation of Paris followed shortly afterwards. The French Resistance in Paris rose against the Germans on 19 August and the French 2nd Armoured Division under General Philippe Leclerc, along with the U.S. 4th Infantry Division pressing forward from Normandy, received the surrender of the German forces there and liberated Paris on 25 August.

Withdrawal to the Seine

Operations continued in the British and Canadian sector until the end of the month. On 25 August, the 2nd U.S. Armored Division fought its way into Elbeuf, making contact with both British and Canadian armoured divisions there.[56] The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division advanced into the Forêt de la Londe, (where German troops had inflicted great loss on French troops in the siege of Paris in 1870—1871) on the morning of 27 August. The area was strongly held and the 4th and 6th Canadian brigades sustained heavy casualties over the course of three days as the Germans fought a delaying action in terrain well-suited to the defense. The Germans pulled back on the 29th, withdrawing over the Seine on the 30th.[56]

On the afternoon of the 30th the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division crossed the Seine near Elbeuf and entered Rouen to a jubilant welcome.[57]

Campaign close

The campaign in Normandy is considered by historians to end either at midnight on 24 July 1944 (the start of Operation Cobra on the American front), 25 August 1944 (the liberation of Paris), or 30 August 1944, the date the last German unit retreated across the River Seine.[58] The original Overlord plan anticipated a ninety-day campaign in Normandy with the ultimate goal of reaching the Seine; this goal was met early. American forces were fighting in Brittany as anticipated by General Montgomery during the latter weeks of the campaign, and their historians consider the Normandy campaign to have ended with the massive breakout of Operation Cobra.[nb 14]

The US official history describes the fighting beginning on 25 July as the "Northern France" campaign, and includes the fighting to close the Falaise Gap, which the British/Canadians/Poles consider to be part of the Battle of Normandy. Volume I of the Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War by C.P. Stacey, published in 1955, as well as the Canadian Army's official Historical Summary of the Second World War, published in 1948, define the Battle of Normandy as lasting from 6 June 1944 to 1 September 1944.[nb 15][60] The definition of the Battle of Normandy is also evident in another publication by the Army's Historical Section entitled Canada's Battle in Normandy.[citation needed]

SHAEF and the governments were very nervous of stagnation, and there were reports of Eisenhower requesting Montgomery's replacement in July.[citation needed] The lack of forward progress is often attributed to the nature of the terrain in which much of the post-landing fighting in the U.S. and parts of the British sectors took place, the bocage (small farm fields separated by high earth banks covered in dense shrubbery, well suited for defence), as well as the usual difficulties of opposed landings. However, as at the battle of El Alamein, Montgomery kept to his original attritional strategy, reaching the objectives within his original ninety day target.[citation needed]

Victory in Normandy was followed by a pursuit to the French border in short order, and Germany was forced once again to reinforce the Western Front with manpower and resources from the Soviet and Italian fronts.

By September, Allied forces of seven field armies (two of which came through southern France in Operation Dragoon) were approaching the German frontier. Allied material weight told heavily in Normandy, as did intelligence and deception plans. The general Allied concept of the battle was sound, drawing on the strengths of both Britain and the United States. German dispositions and leadership were often faulty, despite a creditable showing on the ground by many German units. In larger context the Normandy landings helped the Soviets on the Eastern front, who were facing the bulk of the German forces and, to a certain extent, contributed to the shortening of the conflict there.

Allied logistics, intelligence, morale and air power

Victory in Normandy stemmed from several factors. The Allies ensured material superiority at the critical point (concentration of force) and logistical innovations like the PLUTO pipelines and Mulberry harbours enhanced the flow of troops, equipment, and essentials such as fuel and ammunition. Movement of cargo over the open beaches exceeded Allied planners' expectations, even after the destruction of the U.S. Mulberry in the channel storm in mid-June. By the end of July 1944, one million American, British, Canadian, French, and Polish troops, hundreds of thousands of vehicles, and adequate supplies in most categories were ashore in Normandy. Although there was a shortage of artillery ammunition, at no time were the Allies critically short of any necessity. This was a remarkable achievement considering they did not hold a port until Cherbourg fell. By the time of the breakout the Allies also enjoyed a considerable superiority in numbers of troops (approximately 3.5:1) and armored vehicles (approximately 4:1) which helped overcome the natural advantages the terrain gave to the German defenders.

Allied intelligence and counterintelligence efforts were successful beyond expectations. The Operation Fortitude deception plan before the invasion kept German attention focused on the Pas-de-Calais, and indeed high-quality German forces were kept in this area, away from Normandy, until July. Prior to the invasion, few German reconnaissance flights took place over Britain, and those that did saw only the dummy staging areas. Ultra decrypts of German communications had been helpful as well, exposing German dispositions and revealing their plans such as the Mortain counterattack.

German leadership

Lack of a coherent strategy hampered the German defence. German leadership was split between Field Marshals von Rundstedt and Rommel. Von Rundstedt's staff advocated a strategy of keeping the most powerful units in reserve, mounting a powerful counterattack once the allied landing started. Rommel wanted to stop the allies at the beach, and thought that by the time reserve panzer units could be moved to the invasion site it would be too late. He tried to locate units so that they could counterattack quickly, with minimal allied air power intervention. While Rommel's strategy had promise, the reserve strategy suffered from the inability to move units during the day due to allied air strikes. In the end, following a hybrid of the two strategies proved to be more of a disaster than following one or the other. The beach defences were overcome and the counterattacks, after suffering attrition from allied air power and delays by the French resistance, were not strong enough.

German commanders at all levels failed to react to the assault phase in a timely manner. Communication problems exacerbated the difficulties caused by Allied air and naval firepower. Local commanders also seemed unequal to the task of fighting an aggressive defence on the beach, as Rommel envisioned. The German High Command remained fixated on the Calais area, and von Rundstedt was not permitted to commit the armored reserve. When it was finally released late in the day, success was immeasurably more difficult. Although the 21st Panzer Division, had counterattacked earlier but was stymied by strong opposition that had been allowed to build at the beaches. Overall, despite steadily growing considerable Allied material superiority, the Germans slowed the Allies advance from the bridgehead for nearly two months, aided immeasurably by terrain factors.

Although there were several well-known disputes among the Allied commanders, their tactics and strategy were essentially determined by agreement between the main commanders. By contrast, the senior German leaders were unable to prevent interference by Hitler, who possessed little knowledge of local conditions. Field Marshals von Rundstedt and Rommel repeatedly asked Hitler for more discretion but were refused. Von Rundstedt was removed from his command on 29 June after he bluntly told Field Marshal Keitel, the Chief of Staff at OKW (Hitler's Armed Forces HQ), to "Make peace, you idiots!" Rommel was severely injured by Allied aircraft on 16 July. Field Marshal von Kluge, who took over the posts held by both von Rundstedt and Rommel, was compromised by his association with some of the military plotters against Hitler, and he would not disobey or argue with Hitler for fear of arrest. As a result, the German armies in Normandy were ill-served by Hitler's insistence on counterattack rather than retreat after the American breakthrough. Kluge was relieved of command on 15 August and took his own life shortly afterwards. The more independent Field Marshal Walter Model then took command.

Casualties

Allies

The cost of the Normandy campaign was high for both sides. From D-Day to 21 August, the Allies landed 2,052,299 men in northern France[6] There were around 209,672 Allied casualties from 6 June to the end of August, around 10% of the forces landed in France. The casualties break down to 36,976 killed, 153,475 wounded and 19,221 missing. Split between the Army Groups, the Anglo-Canadian Army Group suffered 16,138 killed, 58,594 wounded and 9,093 missing for a total of 83,825 casualties. The US Army Group suffered 20,838 killed, 94,881 wounded and 10,128 missing for a total of 125,847 casualties. To these casualties it should be added that 4,101 aircraft were lost and 16,714 airmen were killed or missing in direct connection to Operation Overlord. Thus total Allied casualties were 226,386 men.[6]

77 Free French SAS (Special Air Service) were killed and another 200 wounded or prisoners of war from 6 June to the beginning of August in Brittany.[61][62] Allied tank losses have been estimated at around 4,000, of which approximately 2,000 were fighting in American units.[7]

Germany

The German casualties remain unclear.[7] The German forces in France reported losses of 158,930 men between D-Day and 14 August – the night before the start of Operation Dragoon in Southern France.[63] Just in the following battle of the Falaise pocket, a minimum of another 50,000 men were lost in Normandy, of which approximately 10,000 were killed and 40,000 captured.[7] Figures over total casualties stretches from a calculation based on German reports of approximately 210,000 men[7] to estimates between 393,689[64] and 450,000 men. The majority of the German casualties in Normandy consisted of POWs. Allied forces captured at least 200,000 men during the campaigns in France.[63]

There are no exact figures regarding German tank losses in Normandy. Approximately 2,300 tanks and assault guns were committed to the battle of Normandy, of which only 100 to 120 crossed the Seine at the end of the campaign.[4] However, the German forces reported only 481 tanks destroyed between D-day and 31 July.[63] Yet research conducted by No. 2 Operational Research Section, of 21st Army Group, contradicts this German position. Between 6 June and 7 August 1944, 110 destroyed German tanks were examined however "owing to a lack of personnel no Pz Kw MK II and only a small proportion of Pz kw MK IV were examined.". Between 8 August and 31 August, 223 destroyed German tanks were examined, which "is considered to be approximately half the total" of German tank losses during this period.[65] Milton Shulman states "It is safe to say that at least 550 of the 750 tanks deployed in Normandy were destroyed" by the end of July.[66] In just some of the major battles of the campaign, German tank losses amount to over 600 tanks.[nb 16]

Civilians and French heritage

During the course of the liberation of Normandy between 13,632 and 19,890 French civilians were killed.[9] Information held at Caen university concludes that 13,632 civilians were killed, includes the deaths of 7,557 within the Calvados department.[67] Other French sources calculate that the death rate was only 15,000.[68] However, the civilian casualty toll is actually much higher due to the greater number of people who were wounded:[69] for example by D+7 French casualty estimates had reached 22,499.[70] In addition to those who died during the campaign between 11,000 and 19,000 Normans are estimated to have been killed during pre-invasion bombing; the higher figure however is disputed.[9] Following the end of the campaign mines and unexploded ordnance continued to inflict casualties upon the Norman population.[71]

Many cities and towns in Normandy had been totally devastated by the fighting and bombings. In particular by the end of the Battle of Caen there remained only 8,000 livable quarters for a population of over 60,000.[72] Out of Caen’s 210 strong Jewish community, on liberation, only one person had survived the occupation. By the end of the campaign 125,000 inhabitants of the Calvados department had been listed as war victims, including 76,000 who had lost everything including their homes.[73]

Prior to the invasion SHAEF issued instructions (later the basis for the 1954 Hague Convention Protocol I) emphasizing the need to limit the destruction to French heritage sites, including looting and sacrilege. These sites were named in Official Civil Affairs Lists of Monuments, were not to be used by troops unless given express permission from the upper echelons of their chain of command, were defined as "structures or object of historic artistic, scientific, or literary value, or any part or fragment thereof". Eisenhower issued personal instructions that "all measures consistent with military necessity, to avoid damage to all structures, objects, or document of cultural, artistic, archaeological or historical value; and to assist, wherever practicable, in securing them from deterioration consequent upon the process of war".[74] It was established that the German occupation forces had completed similar lists. However, on the seizure of these documents it was determined that they "would not have served to preserve many monuments during an operation" and that they were primarily concerned with ensuring the billets were kept in good order.[75]

By 19 June British Second Army reported that no apparent damage had been caused to monuments in their area. However, as the campaign proceeded so did the levels of damage; by mid-July across Normandy three monuments had been destroyed, 16 damaged and seven seriously. By early August a survey of 69 monuments found seven destroyed, 12 badly damaged, nine damaged, six slightly and the remaining were intact. Other surveys found similar levels of destruction; for example, by the end of the campaign, of 18 Caen’s listed churches five had been destroyed and four seriously damaged while 66 other monuments within the city had been destroyed. In 18 communes, in the Calvados department, monuments had been destroyed and in other locations damaged. A particular example is the Château d'Harcourt, that was destroyed, which contained family records dating back to William the Conqueror. However, the Bayeux Tapestry was located in safe condition at the Château de Sourches in Mid-July and the destroyed roof of the Saint-Sepulcre, in Caen, was temporary repaired by French civilians and Royal Engineers to prevent further degradation of the historical and government records that had been exposed to the elements.[76] Efforts were also made to comb the ruins and debris for artefacts before the rubble was removed.[75]

During the Spring of 1944 French civilians had amassed plenty of evidence of newly arriving German troops looting civilian property;[75] an issue that increased during the battle with all sides, including French civilians, taking part. Well known examples include British forces, generally lines of communication troops and not the infantry, looting Caen’s Musée des antiquaires and Bayeux’s Château d'Andrieu.[75] Looting was never condoned by allied forces and proven perpetrators were punished. This was not the case for German forces.

The Normandy campaign in context

The landings were planned to take place in May 1944, but poor weather conditions and insufficient buildup delayed the landings until June. By then, the Allies had taken Rome in the Italian Campaign, and in the Pacific War, the Americans were launching their first strikes on Japan.

The Normandy landings threatened Hitler's hold on the Belgian and northern French coasts as bases for the "V" weapons, which had started launching against the UK. As the Allies were closing in on Paris and sealing the Falaise Gap, an invasion in southern France was also launched. The linkup with the Allied forces in southern France occurred on 12 September as part of the drive to the Siegfried Line.[77]

On the Eastern Front, the Red Army were planning their own offensive, Operation Bagration, to drive the Germans away from Soviet territory. Combined with the Allied lodgement established at Normandy, the second front in Western Europe that had been demanded by Stalin since the Tehran Conference had been established, the Axis powers were driven back from all fronts.[78]

While the Normandy landings are popularly believed to have signaled the "beginning of the end" for Nazi Germany, it is arguable that Germany's defeat had already been rendered inevitable by its huge losses on the Eastern Front. Germany had already been in almost continuous retreat on the Eastern Front since mid 1943, and the massive German defeats at the Battle of Stalingrad and the Battle of Kursk in early and mid 1943 were arguably more decisive for the course of the war in Europe, whether measured in terms of forces committed, the number of German casualties, or the amount of German war material destroyed. The American historian Jeffrey Herf wrote that, "Whereas German deaths between 1941 and 1943 on the western front had not exceeded 3 percent of the total from all fronts, in 1944 the figure jumped to about 14 percent. Yet even in the months following D-day, about 68.5 percent of all German battlefield deaths occurred on the eastern front, as a Soviet blitzkrieg in response devastated the retreating Wehrmacht".[79]

However, the Normandy landings were the largest seaborne invasion in history, and they did hasten the end of the war in Europe, drawing large forces away from the Eastern Front that might otherwise have slowed the Soviet advance. The opening of a second front in Europe was also a tremendous psychological blow for Germany's military, who had long feared a repetition of the two-front war of World War I. The Normandy landings also heralded the start of the "race for Europe," between the Soviet forces and the Western powers, which some historians consider to be the start of the Cold War.[80]

War memorials and tourism

The beaches of Normandy are still known by their invasion codenames today. Streets near the beaches are still named after the units that fought there, and occasional markers commemorate notable incidents. At significant points, such as Pointe du Hoc and Pegasus Bridge, there are plaques, memorials or small museums. The remains of the Mulberry harbour still sits in the sea at Arromanches. In Sainte-Mère-Église, a mannequin paratrooper hangs from the church spire.

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ "On 25 July there were 812,000 US soldiers and 640,000 British in Normandy".[1]

- ^ "By 21 August, the Allies had landed 2,052,299 men in Normandy". [2][verification needed]

- ^ "When Operation Cobra was launched, the Germans had brought to Normandy about 410,000 men in divisions and non-divisional combat units. If this is multiplied by 1.19 we arrive at approximately 490,000 soldiers. However, until 23 July, casualties amounted to 116,863, while only 10,078 replacements had arrived".[1]

- ^ Shulman states that the Wehrmacht committed well over 1 million men to the Normandy Campaign.[3]

- ^ This is the total number of casualties suffered by the Allied forces up to the end of August. The Allied forces suffered 36,976 killed, 153,475 wounded and 19,221 missing. Split between the Army Groups: the Anglo-Canadian Army Group suffered 16,138 killed, 58,594 wounded and 9,093 missing for a total of 83,825 casualties. The American Army Group suffered 20,838 killed, 94,881 wounded and 10,128 missing for a total of 125,847 casualties.[5]

- ^ To these numbers should also be added the losses of the allied airforces operating. The allied airforces made 480,317 sorties in direct connection to the operation with the loss of 4,101 planes and the lives of 16,696 crewmen.[6]

- ^ Approximately 4000 Allied tanks was destroyed, of which 2000 were fighting in American units.[7]

- ^ Tamelander states that the German army committed 600,000 men to Normandy and 230,000 to Southern France during the period between 1 June and 31 July. Of these forces stationed in France, 288,875 men were lost, a figure that breaks down to 23,019 dead, 67,240 wounded, and 198,616 missing. Tamelander notes that the number of missing corresponds to the number of men reported captured by the Allied forces during the fighting in France and as these figures also include losses from the fighting in Southern France as well as from the following retreat, he suggests roughly 79,000 men should be deducted from this total to give an accurate figure for the Normandy campaign. Total German losses for Normandy thus reach 210,000 men and Tamelander points out that this figure corresponds to the reported losses that previous to Operation Dragoon were 158,930, which together with the losses inflicted by the Falaise pocket reach approximately 210,000 men.[8]

- ^ Shulman claims 240,000 men of the German army had been killed or wounded during the Normandy campaign and a further 210,000 had been taken prisoner.[3] Wilmot supports the figure of 210,000 prisoners being taken during the "10 week campaign".[4]

- ^ Wilmot quotes Günther Blumentritt, von Rundstedt's Chief-of-Staff, who states that around 2,300 tanks and assault guns had been committed to the battle in Normandy and "only 100 to 120 were brought back across the Seine."[4]

- ^ The British 79th Armoured Division never operated as a single formation[30] thus has been excluded from the total. In addition a combind total of 16 (three from the 79th Armoured Division) British, Belgian, Canadian and Dutch independent brigades were committed to the operation along with four battalions of the Special Air Service.[31]

- ^ "The allied D-Day objective-the vital communications centre at Caen"[36]

- ^ "We are told that an immense assault force has begun to leave the shores of Old England to aid us."[44]

- ^ Montgomery wrote of his intent to tie down German armoured forces near Caen in a policy directive on 30 June 1944: "My broad policy, once we had secured a firm lodgement area, has always been to draw the main enemy forces into the battle on our eastern flank, and to fight them there, so that our affairs on the western flank could proceed the easier."[59]

- ^ Both publications are available online from the Directorate of History and Heritage, a department of the Department of National Defence, as free downloads at the Official Histories download page at the Canadian National Defence website

- ^ Sword Beach: 50+ tanks; During the course of Operation Perch through to the end of June saw the loss of over 90 tanks from the Panzer Lehr and 12th SS, as nine Tiger tanks destroyed and a further 21 damaged by 16 June; Operation Epsom: 126 tanks; Operation Charnwood: over 30 tanks; Operation Goodwood: Up to 100 tanks; Operation Totalize: at least 45 tanks; Operation Lüttich: 150 tanks.

- Citations

- ^ a b Zetterling 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Zetterling 2000, p. 341.

- ^ a b c Shulman, p. 192

- ^ a b c d Wilmot 1997, p. 434.

- ^ Ellis, Allen & Warhurst 2004, p. 493.

- ^ a b c d Tamelander & Zetterling 2003, p. 341.

- ^ a b c d e Tamelander & Zetterling 2003, p. 342.

- ^ a b Tamelander & Zetterling 2003, pp. 342–343.

- ^ a b c d Flint 2009, pp. 336–337.

- ^ Churchill 1951, p. 642.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, pp. 627–630.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. [page needed].

- ^ Stacey 1960, p. 295.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 322.

- ^ Bauer, Eddy (1981). Spelet vid konferensbordet (in Swedish). Bokorama. p. 44. ISBN 91-7024-017-5.

- ^ Ambrose 1995, p. [page needed]

- ^ Churchill, Winston (1948). The Second World War book 5, Closing the Ring. Chapter 16, paragraph 1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gilbert 1989, p. 397, 478.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 211.

- ^ Wilmot 1997, pp. 134–135, 171.

- ^ The World At War, episode 17, Morning. 1974. Event occurs at 2:29-3:09.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|person=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ambrose 1995, Chapter 4 Paragraph 4

- ^ Williams 2000, The Atlantic Wall.

- ^ a b Wilmot 1997, p. 170.

- ^ Ambrose 1995, chapter 4 paragraph 10.

- ^ Gilbert 1989, p. 491.

- ^ Hamilton 2004.

- ^ Wilmot 1997, p. 174.

- ^ Ellis, Allen & Warhurst 2004, pp. 521–533.

- ^ Buckley 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Ellis, Allen & Warhurst 2004, pp. 521–523, 524.

- ^ Weinberg 1995, p. 684.

- ^ Wilmot 1997, p. 195.

- ^ "St. Pauls School biographies of famous pupils". pp. paragraph 4. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ Weinberg 1995, p. 698.

- ^ Gilbert 1989, p. 538.

- ^ Sulzberger, C.L. “World War 2” American Heritage Press, New York 1970 pg 279

- ^ a b Weinberg 1995, p. 680.

- ^ "8th Air Force 1944 Chronicles: June". Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ Bickers 1994, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Small, Ken, and Mark Rogerson. The Forgotten Dead - Why 946 American Servicemen Died Off The Coast Of Devon In 1944 - And The Man Who Discovered Their True Story. London: Bloomsbury. 1988. ISBN 0-7475-0309-5

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 667.

- ^ Keegan 1990, p. 279.

- ^ "Text of De Gaulle's message on D-Day" (Press release). SHAEF. 6 June 1944. Retrieved 9 October 2007. [dead link]

- ^ D Day Museum

- ^ Wilmot 1952, p. [page needed].

- ^ Keegan 1997, p. 309.

- ^ Wilmot 1952, pp. 224–226.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (8 June 2000). "The Passing of the Torch". United States Department of Defense. American Forces Press Service. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Ambrose 1994, p. [page needed].

- ^ Corta 1952, p. 159.

- ^ Corta 1997, pp. 65–78.

- ^ Martin 1994, p. 16.

- ^ Video: Cherbourg, Gateway to Victory, 1944/07/02 (1944). Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Weigley 1981, p. 157.

- ^ a b Stacey 1960, p. 286.

- ^ Stacey 1948, p. 219.

- ^ Stacey 1948, p. 295.

- ^ Stacey 1948, p. 195.

- ^ Stacey 1960, p. [page needed].

- ^ Corta 1952, p. many pages.

- ^ Corta 1997, p. many pages.

- ^ a b c Tamelander & Zetterling 2003, p. 343.

- ^ Lecouturier, Y (2000), De stranden van de landing, Editions Ouest-France, p. 109. ISBN 978-2-7373-2686-8

- ^ Copp, Montgomery's Scientists, pp. 399-400

- ^ Shulman, p. 166

- ^ Flint 2009, pp. 336, 370.

- ^ Flint 2009, p. 336.

- ^ Beevor 2009, p. 519.

- ^ Flint 2009, p. 267.

- ^ Flint 2009, p. 305.

- ^ Beevor 2009, p. 520.

- ^ Flint 2009, p. 337.

- ^ Flint 2009, p. 350.

- ^ a b c d Flint 2009, p. 354.

- ^ Flint 2009, p. 352–353.

- ^ Keegan 1997, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Gilbert 1989, pp. 531, 540, 544.

- ^ Herf 2006, p. 252.

- ^ Gaddis 1990, p. 149.

References

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1994). D-Day (First ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80137-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ambrose, Stephen (1995). D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-67334-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beevor, Antony (2009). D-Day:The Battle for Normandy (First ed.). London: Viking an imprint of Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-88703-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bickers, Richard (1994). Air War Normandy. Pen And Sword Books. ISBN 0-85052-412-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Buckley, John (2006) [2004]. British Armour in the Normandy Campaign 1944. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-40773-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Churchill, Winston (1940). "Dieu Protege (sic) la France". London: The Churchill Society. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[clarification needed] - Churchill, Winston (1951) [1st. pub. 1948]. Closing the Ring. The Second World War, Book 5. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 396150.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corta, Henry (1952). Les bérets rouges (Red Berets) (in French). Paris: Amicale des anciens parachutistes SAS.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Henry Corta (1921–1998) was a Free French SAS lieutenant veteran. - Corta, Henry (1997). Qui ose gagne (Who dares wins) (in French). Vincennes, France: Service Historique de l'Armée de Terre. ISBN 978-2-86323-103-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dear, I.C.B.; Foot, M.R.D., eds. (2005) [1995]. The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280666-6.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ellis, L.F.; Allen, G.R.G.; Warhurst, A.E. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1962]. Butler, J.R.M (ed.). Victory in the West, Volume I: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Naval & Military Press Ltd. ISBN 1-84574-058-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Flint, Edwards R (2009). The development of British civil affairs and its employment in the British Sector of Allied military operations during the Battle of Normandy, June to August 1944 (Ph.D. thesis). Cranfield, Bedford: Cranfield University; Cranfield Defence and Security School, Department of Applied Science, Security and Resilience, Security and Resilience Group. OCLC 757064836.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gaddis, John Lewis (1990) [1972]. Russia, the Soviet Union, and the United States An Interpretive History. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780075572589.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gilbert, Martin (1989). Second World War. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-1788-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamilton, Nigel (2004). "Montgomery, Bernard Law [Monty], first Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (1887–1976)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31460.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (subscription required) - Herf, Jeffrey (2006). The Jewish enemy: Nazi propaganda during World War II and the Holocaust. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02175-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keegan, John (1982). Six Armies in Normandy. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-005293-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keegan, John (1990). The Second World War. Harmonsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-011341-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keegan, John (1997) [1989]. The Second World War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-7348-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martin, Charles Cromwell (1994). Battle Diary. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-213-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Raths, Aloyse (2008). Unheilvolle Jahre für Luxemburg - Années néfastes pour le Grand-Duché. Luxembourg: Éd. du Rappel. OCLC 723898422.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stacey, C.P. (1948). The Canadian Army 1939–45: A Historical Summary. Ottawa: Published by Authority of the Minister of National Defence.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stacey, C.P. (1960). The Victory Campaign, The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. Vol. III. Ottawa: Published by Authority of the Minister of National Defence.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)[dead link] - Tamelander, M.; Zetterling, Niklas (2003) [1st. pub. 1995]. Avgörandes Ögonblick: Invasionen i Normandie (in Swedish) (New ed.). Stockholm: Norstedts. ISBN 9789113012049.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Weinberg, Gerhard (1995) [1st pub. 1993]. A world at arms - A global history of World War II. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521558792.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weigley, Russell F. (1981). Eisenhower's Lieutenants: The Campaign of France and Germany 1944-1945. Vol. I. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253133335.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williams, Brian (2000). "The Atlantic Wall". Normandy, France - June 1944. Military history online.com. Retrieved December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williams, Jeffery (1988). The Long Left Flank. London: Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-880-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilmot, Chester (1952). The Struggle for Europe. London: Collins. OCLC 753234755.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilmot, Chester (1997) [This ed. 1st. pub. 1967]. The Struggle For Europe (Revised ed.). Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zetterling, Niklas (2000). Normandy 1944: German Military Organisation, Combat Power and Organizational Effectiveness. J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing Inc. ISBN 0-921991-56-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

![]() D-day from Wiktionary

D-day from Wiktionary

![]() D-day Textbooks from Wikibooks

D-day Textbooks from Wikibooks

![]() D-day Quotations from Wikiquote

D-day Quotations from Wikiquote

![]() D-day Source texts from Wikisource

D-day Source texts from Wikisource

![]() D-day Images and media from Commons

D-day Images and media from Commons

![]() D-day from Wikinews

D-day from Wikinews

- Badsey, Stephen (1990). Normandy 1944: Allied Landings and Breakout. Osprey Campaign Series #1. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0850459214.

- Foot, M. R. D. (1984). SOE. BBC Publications.

- Leighton, Richard M. (2000 (reissue from 1960)). "Chapter 10: Overlord Versus the Mediterranean at the Cairo-Tehran Conferences". In Greenfield, Kent Roberts (ed.). Command Decisions. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-7.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Neillands, Robin (2002). The Battle of Normandy, 1944. Cassell.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2001). Operation Cobra 1944, Breakout from Normandy. Osprey Campaign Series #88. Osprey Publishing.

- Whitlock, Flint (2004). The Fighting First: The Untold Story of The Big Red One on D-Day. Westview.

- Numerous abbreviated summaries have been written. Among the most useful are:

- Charles MacDonald, The Mighty Endeavor: American Armed Forces in the European Theater in World War II (1969); and

- Charles MacDonald and Martin Blumenson, "Recovery of France," in Vincent J. Esposito, ed., A Concise History of World War II (1965).

- Memoirs by Allied commanders contain considerable information. Among the best are:

- Omar N. Bradley, A Soldier's Story (1951);

- Sir Bernard Montgomery, Normandy to the Baltic (1948); and

- Almost as useful are biographies of leading commanders. Among the most prominent are:

- Stephen E. Ambrose, The Supreme Commander: The War Years of General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1970), and Eisenhower, Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890–1952 (1983);

- Richard Lamb, Montgomery in Europe, 1943–1945: Success or Failure (1984).

- Numerous general histories also exist, many centering on the controversies that continue to surround the campaign and its commanders. See, in particular:

- Richard Collier, Fighting Words: The Correspondents of World War II (1989). CMH Pub 72–18

- "Illustrated article about Omaha Beach". Battlefields Europe.[dead link]

- "U.S. Army's official interactive D-Day website".

- "From operation Cobra to the Seine". memorial-montormel.org.[dead link]

- "WW2DB: The Normandy Campaign".

- "Second World War Newspaper Archives—D-Day Invasion and the Normandy Campaign".[dead link]

- "Encyclopaedia Britannica Guide to Normandy 1944". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Overlord, Underhand (2013), by the American author Robert P. Wells (novelist) is a fictionalized retelling of the story of Juan Pujol Garcia (Agent Garbo), double-agent with MI5, and his role in deceiving the German High Command about "Operation Overlord". ISBN 978-1-63068-019-0.

External links

- Documents available online from the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Guide to materials at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Guide to materials on the planning of Operation Overlord at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Booknotes interview with Stephen Ambrose on D-Day: June 6, 1944, June 5, 1994.

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Use dmy dates from August 2010

- World War II invasions

- Operation Neptune

- Battles and operations of World War II involving Canada

- Battles and operations of World War II involving France

- Battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Battles and operations of World War II involving the United States

- Code names

- 1944 in France

- Operation Overlord