Sailor Moon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

| Sailor Moon | |

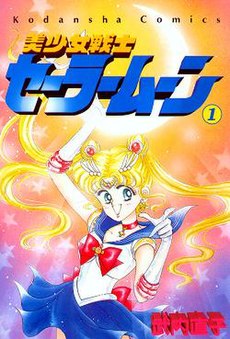

The first cover of the Sailor Moon manga as published by Kodansha on July 6, 1992 in Japan. | |

| 美少女戦士セーラームーン (Bishōjo Senshi Sērāmūn) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Magical girl Romantic Dramedy Action Adventure |

| Manga | |

| Written by | Naoko Takeuchi |

| Published by | Kodansha |

| English publisher |

|

| Magazine | Nakayoshi, Run Run |

| English magazine | |

| Demographic | Shōjo |

| Original run | February 1992 – March 1997 |

| Volumes | 18 (first edition) 12 (second edition) |

| Anime television series | |

| Directed by | Junichi Sato |

| Written by | Sukehiro Tomita |

| Music by | Takanori Arisawa |

| Studio | Toei Animation |

| Original network | TV Asahi |

| English network | |

| Original run | March 7, 1992 – February 27, 1993 |

| Episodes | 46 |

| Anime television series | |

| Sailor Moon R | |

| Directed by | Kunihiko Ikuhara |

| Written by | Sukehiro Tomita |

| Music by | Takanori Arisawa |

| Studio | Toei Animation |

| Original network | TV Asahi |

| English network | |

| Original run | March 6, 1993 – March 12, 1994 |

| Episodes | 43 |

| Anime television series | |

| Sailor Moon S | |

| Directed by | Kunihiko Ikuhara |

| Written by | Yoji Enokido |

| Music by | Takanori Arisawa |

| Studio | Toei Animation |

| Original network | TV Asahi |

| English network | |

| Original run | March 19, 1994 – February 25, 1995 |

| Episodes | 38 |

| Anime television series | |

| Sailor Moon SuperS | |

| Directed by | Kunihiko Ikuhara |

| Written by | Yoji Enokido |

| Music by | Takanori Arisawa |

| Studio | Toei Animation |

| Original network | TV Asahi |

| English network | |

| Original run | March 4, 1995 – March 2, 1996 |

| Episodes | 39 |

| Anime television series | |

| Sailor Moon Sailor Stars | |

| Directed by | Takuya Igarashi |

| Written by | Ryota Yamaguchi |

| Music by | Takanori Arisawa |

| Studio | Toei Animation |

| Original network | TV Asahi |

| Original run | March 9, 1996 – February 8, 1997 |

| Episodes | 34 |

| Anime television series | |

| Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon Crystal | |

| Directed by | Munehisa Sakai |

| Written by | Yuji Kobayashi |

| Music by | Yasuharu Takanashi |

| Studio | Toei Animation |

| Original network | Niconico |

| Original run | July 31, 2014 – present |

| Movies/Films | |

| Stage musical series | |

|

Sailor Moon musicals (SeraMyu): 25 stage shows based on the Sailor Moon franchise were released between 1993 and 2005. | |

| Live-action series | |

|

Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon: a 49 episode live action series directed by Ryuta Tasaki ran from October 4, 2003, to September 25, 2004. There were also two direct-to-video releases: a sequel (Special Act), and a prequel (Act Zero). | |

| Video games | |

| |

| Related series | |

Sailor Moon, known in Japan as Pretty Soldier Sailormoon[1][2][3] or Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon[4] (美少女戦士セーラームーン, Bishōjo Senshi Sērāmūn), is a Japanese multimedia franchise series which originated as a manga written and illustrated by Naoko Takeuchi. Fred Patten credits Takeuchi with popularizing the concept of a team of magical girls,[5][6] and Paul Gravett credits the series with revitalizing the magical girl genre itself.[7] Sailor Moon redefined the magical girl genre, as previous magical girls did not use their powers to fight evil, but this has become one of the standard archetypes of the genre.[8]

The story of the various metaseries revolves around the reborn defenders of a kingdom that once spanned the Solar System and the evil forces that they battle. The major characters – the Sailor Senshi (literally "Sailor Soldiers"; called "Sailor Scouts" or "Guardians" in Western versions) – are teenage girls who can transform into heroines named for the Moon and planets. The use of "Sailor" comes from a style of girls' school uniform popular in Japan, the sērā fuku ("Sailor outfit"), on which Takeuchi modeled the Sailor Senshi's uniforms.[9] The fantasy elements in the series are heavily symbolic and often based on mythology.[10]

Before writing Sailor Moon, Takeuchi had written Codename: Sailor V, which centered around just one Sailor Senshi. She devised the idea when she wanted to create a cute series about girls in outer space, and her editor suggested she should put them in sailor fuku.[9] When Sailor V was proposed by Toei for adaptation into an anime, the concept was modified by Takeuchi so that Sailor V herself became only one member of a team.[11][12] The resulting manga series merged elements of the popular magical girl genre and the Super Sentai Series which Takeuchi admired,[13] making Sailor Moon the first series ever to combine the two.

The manga resulted in spinoffs into other types of media, including an anime adaptation, musical theatre productions, video games, and a tokusatsu (live action drama) series. Although most concepts in the many versions overlap, often notable differences occur, and thus continuity between the different formats remains limited.

Plot

Sailor Moon follows Usagi Tsukino, an ordinary and ditzy 14-year-old – or so she thinks – who one day discovers Luna, a talking cat who reveals Usagi's identity as "Sailor Moon", a magical warrior destined to save Earth from the forces of evil. Luna tasks her with finding the Moon Princess and protecting Earth from a series of antagonists, beginning with the Dark Kingdom that appeared once before a long time ago and destroyed the Moon Kingdom. Before the start of the series, when the dark nemesis attacked the Moon Kingdom, the Queen sent the Moon Princess, her guardians, her advisors, and her true love into the future to be reborn. Together with the Moon Princess's guardians — the intelligent Sailor Mercury, psychic Sailor Mars, tomboyish Sailor Jupiter, and cheerful Sailor Venus — she fights evil and periodically encounters the mysterious Tuxedo Mask, the Moon Princess's true love.

As the series progresses, Usagi and her friends learn more and more about the enemies they face and the evil force that directs them. The characters' pasts are mysterious and hidden even to them, and much of the early series is devoted to rediscovering their true identities and pasts. Luna, who guides and advises the Sailor Senshi, does not know everything about their histories either, and the Senshi eventually learn that Usagi is the real Moon Princess; the Moon Princess's mother had her reborn as a Sailor Senshi to protect her. Gradually Usagi discovers the truth about her own past life, her destined true love, and the possibilities for the future of the Solar System.

In later seasons, the protagonists are joined by Chibiusa, Sailor Moon and Tuxedo Mask's daughter from the future who travels back in time to the series' events, and four additional Senshi — the masculine-acting Sailor Uranus, elegant Sailor Neptune, distant Sailor Pluto, and lonely Sailor Saturn. After the Dark Kingdom, the Senshi encounter more groups of villains, including the Black Moon Clan, the Death Busters, the Dead Moon Circus and Shadow Galactica.

Production

Before the Sailor Moon manga, Takeuchi published Codename: Sailor V, which focused on Sailor Venus. She devised the idea when she wanted to create a cute series about girls in outer space, and her editor asked her to put them in sailor fuku.[9] When Sailor V was proposed for adaptation into an anime, the concept was modified so that Sailor V herself became only one member of a team. The resulting manga series became a fusion of the popular magical girl genre and the Super Sentai Series, of which Takeuchi was a fan.[13] Recurring motifs include astronomy,[9] astrology, Greek myth,[10] Roman myth, geology, Japanese elemental themes,[14] teen fashions,[10][15] and schoolgirl antics.[15]

Discussions between Takeuchi and her publishers originally envisaged only one story arc,[16] and the storyline developed in meetings a year prior to publications,[17] but having completed it, Takeuchi was asked by her editors to continue. She issued four more story arcs,[16] often published simultaneously with the five corresponding anime series. The anime series would only lag the manga by a month or two.[17] As a result, "the anime follows the storyline of the manga fairly closely".[18] Takeuchi has stated that due to the largely male production staff of the anime, she feels that the anime version has "a slight male perspective".[18]

Takeuchi intended to have all the main characters die in the end, but her editor would not let her, stating, "This is a shōjo manga!" When the anime adaptation was created, all of the protagonists were in fact killed off, although they came back to life, and Takeuchi held a bit of a grudge that she had not been allowed to do that in her version.[19]

Media

Manga

Written and illustrated by Naoko Takeuchi, Sailor Moon spans 52 chapters, known as Acts, and ten separate side-stories. It appeared as a serial in Kodansha's monthly manga magazine Nakayoshi from the February 1992 issue to the March 1997 issue;[20] the side-stories appeared simultaneously in another of Kodansha's manga magazines, RunRun.[20] Kodansha has published all the chapters and side-stories in book form. The first collected edition of the manga was published from 1992 through 1997[21][22] and consisted of 18 volumes with all the chapters and side stories in the order in which they had been released. By the end of 1995, the thirteen Sailor Moon volumes then available had sold about one million copies each, and Japan had exported the manga to over 23 countries, including China, Mexico, Australia, most of Europe and North America.[23]

The second collected edition, called the shinsōban or "renewal" edition, began in 2003 during the run of the live-action series.[24] Kodansha redistributed the individual chapters so that there were more per book, and some corrections and updates were made to the dialogue and drawings.[citation needed] New art was featured as well, including completely new cover art and character sketches (including characters unique to the live action series).[citation needed] The second edition consisted of 12 main volumes and two separate short story volumes.[citation needed]

The third collected edition, called the kanzenban or "complete" edition, began in November 2013 to commemorate the manga's 20th anniversary, with the plan to release two volumes per month. The interior artwork has been digitally remastered while brand new artwork has been created for the covers and all color pages that were printed in the original serialization have been included in this edition. The books themselves have been enlarged from the typical Japanese manga size to A5.[25][26] The short stories will be republished in two volumes, with the order of the stories reshuffled, while Codename: Sailor V will also be included within the third edition.[26]

Anime

Toei Animation produced an anime television series based on the manga. The series, also titled Sailor Moon, began airing in Japan on March 7, 1992 and ended on February 8, 1997. The series spans 200 episodes, and is one of the longest-running magical girl anime series.[citation needed] Sailor Moon sparked a highly successful merchandising campaign of over 5,000 items,[10] which contributed to demand all over the world and translation into numerous languages. Sailor Moon has since become one of the most famous anime properties in the world.[27][28] Due to its resurgence of popularity in Japan, the series was rebroadcast on September 1, 2009. The series also began rebroadcasting in Italy in Autumn 2010, receiving permission from Naoko Takeuchi, who released new artwork to promote its return.[29]

Sailor Moon consists of five separate arcs. The titles of the series are Sailor Moon, Sailor Moon R, Sailor Moon S, Sailor Moon SuperS and Sailor Moon Sailor Stars. Each series roughly corresponds to one of the five major story arcs of the manga, following the same general storyline and including most of the same characters.[17] There were also five special animated shorts, as well as three theatrically released films: Sailor Moon R: The Movie, Sailor Moon S: The Movie, and Sailor Moon SuperS: The Movie.[30][31][32]

The anime series was directed by Junichi Satō, Kunihiko Ikuhara and Takuya Igarashi. Character design was headed by Kazuko Tadano, Ikuko Itoh and Katsumi Tamegai, all of whom were also animation directors. Other animation directors included Masahiro Andō, Hisashi Kagawa, and Hideyuki Motohashi.[33]

The anime series was sold as twenty volumes in Japan. By the end of 1995, each volume had sold approximately 300,000 copies.[23]

At the July 6, 2012 event celebrating the 20th anniversary of Sailor Moon, Naoko Takeuchi, Kodansha and idol group Momoiro Clover Z announced that a new anime adaptation was in production and scheduled to begin broadcasting in Summer 2013 for a simultaneous worldwide release,[34][35] with Momoiro Clover Z performing both the opening and ending theme music.[36] However in April 2013, it was announced that the new anime had been delayed.[37] It was later confirmed on August 4, 2013 that the new anime will be streamed in the Winter.[36] On January 9, 2014, it was announced that the new anime will premiere in July.[38] On March 13, 2014, the official website for the new anime was updated to reveal a countdown (beginning on March 14), regarding a special announcement that will be revealed on March 21, 2014.[39] That same day, an image displaying the key visual art, synopsis and staff for the new anime was leaked on to Toei's website, revealing the name for the anime, Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon Crystal.[40]

Art books

Kodansha released special art books for each of the five story arcs, collectively called the Original Picture Collection. The books contain cover art, promotional material, and other work done by Takeuchi. Many of the drawings appear accompanied by comments on how she developed her ideas, how she created each picture, whether or not she likes it, and commentary on the anime interpretation of her story.[41][42][43][44][45]

Another picture collection, Volume Infinity, appeared in a strictly limited edition after the end of the series in 1997. This self-published artbook includes drawings by Takeuchi as well as by her friends, her staff, and many of the voice-actors who worked on the anime. In 1999, Kodansha published the Materials Collection; this contained development sketches and notes for nearly every character in the manga, as well as for some characters who never appeared. Each drawing is surrounded with notes by Takeuchi about the specifics of various costume pieces, the mentality of the characters, and her particular feelings about them. It also includes timelines for the story arcs and for the real-life release of products and materials relating to the anime and manga. At the end, the Parallel Sailor Moon short story is featured, celebrating the year of the rabbit.[46]

Stage musicals

The musical stage shows, usually referred to collectively as SeraMyu, were a series of live theatre productions that played over 800 performances in some 29 musicals between 1993 and 2005. The stories of the shows include anime-inspired plotlines as well as a large amount of original material. Music from the series has been released on about 20 "memorial" albums.[47] The popularity of the musicals has been cited as a reason behind the production of the live action Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon TV series.[48]

Musicals ran twice a year, in the winter and in the summer. In the summer, the musicals showed only in the Sunshine Theatre in the Ikebukuro area of Tokyo; however, in the winter they went on tour to the other large cities in Japan, including Osaka, Fukuoka,[49] Nagoya, Shizuoka, Kanazawa, Sendai,[50] Saga, Oita, Yamagata and Fukushima.[51]

The final incarnation of the series, The New Legend of Kaguya Island (Revised Edition) (新・かぐや島伝説 <改訂版>, Shin Kaguyashima Densetsu (Kaiteban)), went on stage in January 2005. Following that show, Bandai officially put the series on a hiatus.[52]

On June 2, 2013, it was announced that the Sailor Moon musicals would begin again in September 2013.[53][better source needed]

Trading figures

Megahouse will release a set of Sailor Moon trading figures for release in early 2014, consisting of twelve figurines, two for each Senshi and two for Tuxedo Mask.[54]

Live-action series

The Tokyo Broadcasting System and Chubu-Nippon Broadcasting screened a tokusatsu version of Sailor Moon from October 4, 2003 through September 25, 2004. The series, titled Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon (often shortened to "PGSM"), used an entirely English-language title for the first time in the Sailor Moon franchise. It lasted a total of 49 episodes.[55][56]

The series' storyline more closely follows the original manga than the anime at first, but in later episodes it proceeds into a significantly different storyline from either, with original characters and new plot developments.[48][57]

In addition to the main episodes, two direct-to-video releases appeared after the show ended its television broadcast. These were the "Special Act", which is set four years after the main storyline ends and which shows the wedding of the two main characters, and "Act Zero", a prequel which shows the origins of Sailor V and Tuxedo Mask.[58]

Video games

More than 20 Sailor Moon console and arcade games have appeared in Japan, all based on the anime series. Bandai and a Japanese game company called Angel (unrelated to the American-based Angel Studios, as of 2010[update] known as Rockstar San Diego) made most of them, with some produced by Banpresto. The early games were side-scrolling fighters, whereas the later ones were unique puzzle games, or versus fighting games. Another Story was a turn-based role-playing video game.[59]

The only Sailor Moon game produced outside of Japan, 3VR New Media's The 3D Adventures of Sailor Moon, went on sale in North America in 1997.[60]

A video game was released in Spring 2011 for the Nintendo DS, called Sailor Moon: La Luna Splende (Sailor Moon: The Shining Moon).[61]

English adaptations

The English adaptations of both the manga and anime series became the first successful shōjo title in the United States.[62] The anime adaptation of Sailor Moon attempted to capitalize on the success of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers.[15][63] After a bidding-war between Toon Makers, who wanted to produce a half live-action and half American-style cartoon version,[64] and DIC Entertainment, DiC — then owned by The Walt Disney Company[65] — and Optimum Productions acquired the rights to the first two seasons of Sailor Moon,[66] from which they cut a total of six episodes (five from the first season and one from the second season) and merged the final two episodes of the first season into one.[citation needed] Editors cut each of the remaining episodes by several minutes to make room for more commercials, to censor plot points or visuals deemed inappropriate for children, and to allow the insertion of "educational" segments called "Sailor Says" at the end of each episode.[citation needed] The second season, named Sailor Moon R in Japan, was dubbed solely as Sailor Moon with the "R" removed from the logo.

The English adaptations of Sailor Moon S and Sailor Moon Super S, produced by Optimum Productions and Cloverway, stayed relatively close to the original Japanese versions, without skipping or merging any episodes.[citation needed] Some controversial changes were made, however, such as the depiction of Sailors Uranus and Neptune as cousins rather than lesbian lovers.[67]

Toei has never licensed the fifth and final series, Sailor Stars, for adaptation into English. In 2004, the rest of the media franchise officially went off the air in all English-speaking countries due to lapsed and unrenewed licenses.[68]

The manga publisher Mixx (later Tokyopop) translated the Sailor Moon manga into English in 1997. The manga initially appeared as a serial in MixxZine but was later pulled out of that magazine and made into a separate monthly comic to finish the first through third arcs. At the same time, the fourth and fifth arcs began printing in a secondary magazine called Smile.[69] The series was later reprinted into three parts—Sailor Moon, Sailor Moon SuperS, and Sailor Moon: StarS—spanning eighteen volumes which were published from December 1, 1998, to September 18, 2001.[70][71] Tokyopop's translation officially went out of print on May 2, 2005, after the license expired,[72] but was later revived by Kodansha Comics USA in association with Random House. Kodansha Comics USA published the main series in twelve volumes simultaneously with the two-volume edition of Codename Sailor V, from September 2011 to July 2013.[73][74][75] The first volume of the two related short stories was published on September 10, 2013,[76] with the other published on November 26.[77]

Music

Numerous people wrote and composed music for the Sailor Moon metaseries, with frequent lyrical contributions by creator Naoko Takeuchi. Takanori Arisawa, who earned the "Golden Disk Grand Prize" from Columbia Records for his work on the first series soundtrack in 1993, composed and arranged the background musical scores, including the spinoffs, games, and movies. In 1998, 2000, and 2001 he won the JASRAC International Award for most international royalties, owing largely to the popularity of Sailor Moon music in other nations.[78]

Most of the TV series used for an opening theme "Moonlight Densetsu" (ムーンライト伝説, Mūnraito Densetsu, lit. "Moonlight Legend"), composed by Tetsuya Komoro with lyrics by Kanako Oda. It was one of the series' most popular songs. "Moonlight Densetsu" was performed by DALI as the opener for the first two anime series,[79][80] and then by Moon Lips for the third and fourth.[81][82] The final series, Sailor Stars, switched to using "Sailor Star Song" for its opening theme, written by Shōki Araki with lyrics by Naoko Takeuchi and performed by Kae Hanazawa.[83] "Moonlight Densetsu" made its final appearance as the closing song for the very last episode, #200.[33]

The English-language dub of the anime series used the melody of "Moonlight Densetsu", but with very different lyrics. At the time, it was unusual for anime theme songs to be translated, and this was one of the first such themes to be redone in English since Star Blazers.[84] The English theme has been described as "inane but catchy".[85] The Japanese theme is a love song based on the relationship between Usagi and Mamoru ("born on the same Earth"); its first verse, as it appears in the English subtitles, is as follows:[86]

- I'm sorry I'm not straightforward,

- I can say it in my dreams

- My thoughts are about to short circuit,

- I want to see you right now

The English "Sailor Moon Theme" rather resembles a superhero anthem. Its first verse is written:[87]

- Fighting evil by moonlight,

- Winning love by daylight,

- Never running from a real fight,

- She is the one named Sailor Moon

Moonlight Densetsu was released as a CD single in March 1992, and was an "explosive hit".[88] "Moonlight Densetsu" won first place in the Song category in Animage's 15th and 16th Anime Grand Prix.[89][90] It came seventh in the 17th Grand Prix, and "Moon Revenge", from Sailor Moon R: The Movie, came eighth.[91] "Rashiku Ikimasho", the second closing song for SuperS, placed eighteenth in 1996.[92] In 1997, "Sailor Star Song", the new opening theme for Sailor Stars, came eleventh, and "Moonlight Densetsu" came sixteenth.[93]

Reception

The manga won the Kodansha Manga Award in 1993 for shōjo.[94]

Originally planned to run for only six months, the Sailor Moon anime repeatedly continued due to its popularity, concluding after a five-year run.[95] In Japan, it aired every Saturday night in prime time,[10][96] getting TV viewership ratings around 11-12% for most of the series run.[10][97] Commentators detect in the anime adaptation of Sailor Moon "a more shonen tone", appealing to a wider audience than the manga, which aimed squarely at teenage girls.[98] The media franchise became one of the most successful Japan has ever had, reaching 1.5 billion dollars in merchandise sales during the first three years. Ten years after the series completion, the series featured among the top thirty of TV Asahi's Top 100 anime polls in 2005 and 2006.[27][28] The anime series won the Animage Anime Grand Prix prize in 1993.[89] Sales of Sailor Moon fashion-dolls overtook those of Licca-chan in the 1990s; Mattel attributed this to the "fashion-action" blend of the Sailor Moon storyline. Doll accessories included both fashion items and the Senshi's weapons.[15]

Sailor Moon has also become popular internationally. Spain and France became the first countries outside of Japan to air Sailor Moon, beginning in December 1993.[30] Other countries followed suit, including Australia, South Korea, the Philippines (Sailor Moon became one of its carrier network's main draws, helping it to become the third-biggest network in the country), Poland, Italy, Peru, Brazil, Sweden and Hong Kong, before North America picked up the franchise for adaptation.[99] In 2001, the Sailor Moon manga was Tokyopop's best selling property, outselling the next-best selling titles by at least a factor of 1.5.[100] In Diamond Comic Distributors's May 1999 "Graphic Novel and Trade Paperback" category, Sailor Moon Volume 3 ranked #1 in sales of all the comic books sold in the United States.[101]

Critics have commended the anime series for its portrayal of strong friendships,[102] as well as for its large cast of "strikingly different" characters who have different dimensions and aspects to them as the story continues,[103] and for an ability to appeal to a wide audience.[104] Writer Nicolas Penedo attributes the success of Sailor Moon to its fusion of the shōjo manga genre of magical girls with the Super Sentai fighting teams.[98] According to Martha Cornog and Timothy Perper, Sailor Moon became popular because of its "strongly-plotted action with fight scenes, rescues" and its "emphasis on feelings and relationships", including some "sexy romance" between Usagi and Mamoru.[105] The romance of Usagi and Mamoru has been seen as an archetype where the lovers "become more than the sum of their parts", promising to be together forever.[106] In contrast, others see Sailor Moon as campy[57] and melodramatic. Criticism has singled out its use of formulaic plots, monsters of the day,[107] and stock footage.[108]

Drazen notes that Sailor Moon has two kinds of villains, the Monster of the Day and the "thinking, feeling humans". Although this is common in anime and manga, it is "almost unheard of in the West".[109] Despite the series' apparent popularity among Western anime fandom, the dubbed version of the series received poor ratings in the United States when it was initially broadcast in syndication and did not do well in DVD sales in the United Kingdom.[110] Anne Allison attributes the lack of popularity in the United States primarily to poor marketing (in the United States, the series was initially broadcast at times which did not suit the target audience - weekdays at 9:00 a. m. and 2:00 pm). Executives connected with Sailor Moon suggest that poor localization played a role.[15] Helen McCarthy and Jonathan Clements go further, calling the dub "indifferent", and suggesting that Sailor Moon was put in "dead" timeslots due to local interests.[111] The British distributor, MVM Films, has attributed the poor sales to the United Kingdom release being of the dub only, and that major retailers refused to support the show leading to the DVD release appealing to neither children nor older anime fans.[110]

Both the manga editorial vid and the anime series were released in Mexico twice in a quite accurate translation in Imevisión (what is now Azteca), which also aired almost complete versions of Saint Seiya, Senki, Candy Candy, Remi, Nobody's Girl, Card Captor Sakura and Detective Conan. With quite a success and in the U. S. censored version in the Cartoon Network that was very quickly taken off the air due to the lack of viewers being lackluster compared to the original version; due to sensitive or controversial topics a Catholic parents' group exerted pressure to take it off the market, which partially succeeded - but after the whole series had been aired once from Sailor Moon to Sailor Stars and some of the movies.[112]

Due to anti-Japanese sentiment, most Japanese media other than animated ones was banned for many years in South Korea.[citation needed] A producer in KBS "did not even try to buy" Sailor Moon because he thought it would not pass the censorship laws, but as of May 1997, Sailor Moon was airing on KBS 2 without issues and was "enormously" popular.[113]

In his 2007 book Manga: The Complete Guide, Jason Thompson gave the manga series 3 / 4 stars. He enjoyed the blending of shōnen and shōjo styles, stating that the combat scenes seemed heavily influenced by Saint Seiya, but shorter and less bloody, and noting that the manga itself appeared similar to Super Sentai television shows. While Thompson found the series fun and entertaining, the repetitive plot lines were a detriment to the title which the increasing quality of art could not make up for; even so, he still states that the series is "sweet, effective entertainment".[62] Thompson states that although the audience for Sailor Moon is both male and female, Takeuchi does not use excessive fanservice for males, which would run the risk of alienating her female audience. Thompson states that fight scenes are not physical and "boil down to their purest form of a clash of wills", which he argues "makes thematic sense" for the manga.[114]

When comparing the manga and anime, Sylvian Durand first notes that the manga artwork is gorgeous, but that the storytelling is more compressed and erratic, and that the anime has more character development. Durand felt "the sense of tragedy is greater" in the manga's telling of the "fall of the Silver Millennium", giving more detail on the origins of the Shitennou and on Usagi's final battle with Beryl and Metalia. Durand feels that the anime leaves out information which makes the story easier to understand, but judges the anime more "coherent", with a better balance of comedy and tragedy, whereas the manga is "more tragic" and focused on Usagi and Mamoru's romance.[115]

For the week of 11 September 2011 - 17 September 2011, the first volume of the re-released Sailor Moon manga was the bestselling manga on the The New York Times Manga Best Sellers list, with the first volume of Codename: Sailor V in second place.[116][117] The first print run of the first volume sold out after four weeks.[118]

Legacy

The manga and anime series has been cited as reinvigorating the magical girl genre by adding dynamic heroines and action-oriented plots. After its success, many similar magical girl series, such as Magic Knight Rayearth, Wedding Peach, Nurse Angel Ririka SOS, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Fushigi Yuugi and Pretty Cure, emerged.[119][120] Sailor Moon has been called "the biggest breakthrough" in English dubbed anime up until 1995, when it premiered on YTV,[99] and "the pinnacle of little kid shōjo anime".[121] Matt Thorn notes that soon after Sailor Moon, shōjo manga began to be featured in book shops, as opposed to fandom-dominated comic shops.[122] It is credited as the beginning of a wider movement of girls taking up shōjo manga.[62][123][124] Gilles Poitras defines a "generation" of anime fans as those who were introduced to anime by Sailor Moon in the 1990s, noting that they were both much younger than the other fans and also mostly girls.[120]

Fred Patten credits Takeuchi with popularizing the concept of a Super Sentai-like team of magical girls,[5][6] and Paul Gravett credits the series with "revitalizing" the magical girl genre itself.[7] The series is credited with changing the genre of magical girls — its heroine must use her powers to fight evil, not simply to have fun as previous magical girls had done.[8]

In the West, people sometimes associated Sailor Moon with the feminist or Girl Power movements and with empowering its viewers,[123] especially regarding the "credible, charismatic and independent" characterizations of the Sailor Senshi, which were "interpreted in France as an unambiguously feminist position. "[98] Although Sailor Moon is regarded as empowering to girls, and feminist in concept through the aggressive nature and strong personalities of the Sailor Senshi,[125] it is a specific type of feminist concept where "traditional feminine ideals [are] incorporated into characters that act in traditionally male capacities".[125] Whilst the Sailor Senshi are strong, independent fighters who thwart evil (which is generally a masculine stereotype), they are also ideally feminized through the transformation of the Sailor Senshi from teenage girls to magical girls which heavily emphasizes on jewellery, make-up, and their highly-sexualized outfits (cleavage, short skirt, and accentuated waist).[10] The most notable hyper-feminine features of the Sailor Senshi (and most other females in Japanese girls’ comics) are the girls’ thin bodies, extremely long legs, and, in particular, round, orb-like eyes.[10] Eyes are commonly known as the primal source within characters where emotion is evoked – sensitive characters have larger eyes than insensitive ones.[125] Male characters generally have smaller eyes and do not contain a sparkle or shine in them like the eyes of the female characters.[125] The stereotypical role of women in Japanese culture is to undertake ‘romantic’ and ‘loving’ feelings;[10] therefore, the prevalence of hyper-feminine qualities like the openness of the female eye (in Japanese girls’ comics) is clearly exhibited in Sailor Moon, as well. Thus, Sailor Moon emphasizes a type of feminist model by combining traditional masculine action with traditional female affection and sexuality through the Sailor Senshi.[125] Its characters have been described as "catty stereotypes", with Sailor Moon's character in particular being singled out as less-than-feminist.[126]

Sailor Moon has also been compared with Mighty Morphin Power Rangers,[10][102] Buffy the Vampire Slayer,[127][128][129] and Sabrina, the Teenage Witch.[130]

James Welker believes that Sailor Moon's futuristic setting helps to make lesbianism "naturalized" and a peaceful existence. Yukari Fujimoto notes that although there are few "lesbian scenes" in Sailor Moon, it has become a popular subject for yuri parodic dōjinshi. She attributes this to the source work's "cheerful" tone, although she notes that "though they seem to be overflowing with lesbians, the position of heterosexuals is earnestly secured".[131]

In English-speaking countries, Sailor Moon developed a cult following amongst various anime fans and male university students,[10] and Drazen considers that the Internet was a new medium that fans used to communicate and played a role in the popularity of Sailor Moon.[127] Fans could use the Internet to communicate about the series, using it to organize campaigns to return Sailor Moon to U. S. broadcast, and to share information about episodes that had not yet aired, or to write fan fiction.[126][132] In 2004, one study suggested there were 3,335,000 sites about Sailor Moon, compared to 491,000 for Mickey Mouse.[133] NEO magazine suggested that part of Sailor Moon's allure was that fans communicated, via the Internet, about the differences between the dub and the original version.[134] The Sailor Moon fandom was described in 1997 as being "small and dispersed".[135] In a United States study, children paid rapt attention to the fighting scenes in Sailor Moon, although when questioned if Sailor Moon was "violent" only two would say yes, the other ten preferring to describe the episodes as "soft" or "cute".[136]

International revival

In 2010, Toei offered 200 refurbished episodes of Sailor Moon at MIPTV.[137] Toei has started to license the refurbished Sailor Moon episodes to countries which the show has not been aired before, like Israel, which began airing on January 2011. In December 2011 Sailor Moon was aired for the third time (after 1995 and 2000) in Poland.[138]

In 2009, Funimation Entertainment announced that it was considering an entire re-dub of the Sailor Moon series and asked people to take part in a survey on what their next project should be. The re-dub of the Sailor Moon series was included. The results of the survey have not been released to the public.[139]

In 2011, Kodansha USA announced that it would publish the Sailor Moon manga in English, along with the lead in series Codename: Sailor V, both were released on September 13, 2011.[140] The manga continues to be released bimonthly[141][142][143] with the next Sailor Moon and Codename: Sailor V volumes being released on November 15, 2011.[141][144][145]

In 2012, Takeuchi, Kodansha, and Momoiro Clover Z announced that a new Sailor Moon anime is in production and was scheduled to premiere in summer 2013 for a simultaneous worldwide release in celebration of its 20th anniversary.[34] However, the new anime has since been delayed. The new series is set to premiere in July 2014.[38]

References

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (August 1994). Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon Volume I Original Picture Collection. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-324507-1.

- ^ "Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon SuperS: Piano Fantasia". Sailormusic.net. 1995-09-21. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ "TV Series Theme Song Collection [Memorial Song Box Disc 1]". Sailormusic.net. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ "美少女戦士セーラームーン 完全版 第3巻、第4巻が発売開始" (in Japanese). sailormoon-official.com. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- ^ a b "Atsukamashii Onna - Taking One for the Team: A Look at Sentai Shows (vol V/iss 11/November 2002)". Sequential Tart. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ a b Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews by Fred Patten page 50

- ^ a b Paul Gravett (2004) Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics (Harper Design, ISBN 1-85669-391-0) page 78

- ^ a b "THEM Anime Reviews 4.0 - Sailor Moon". Themanime.org. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ a b c d Takeuchi, Naoko (September 2003). Sailor Moon Shinsouban Volume 2. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-334777-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Grigsby, Mary. "Sailormoon: Manga (Comics) and Anime (Cartoon) Superheroine Meets Barbie: Global Entertainment Commodity Comes to the United States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2012.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (December 18, 1993). "Vol. 1". Codename wa Sailor V Book 1. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-322801-0.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (September 29, 2004). "Vol. 1". Codename wa Sailor V Shinsouban Book 1. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-334929-2.

- ^ a b "Public Interview with Takeuchi Naoko". Ex.org. Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ Drazen, Patrick (October 2002). Anime Explosion! The What? Why? & Wow! Of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 286. ISBN 1-880656-72-8. OCLC 50898281.

- ^ a b c d e Allison, Anne (2000). "A Challenge to Hollywood? Japanese Character Goods Hit the US". Japanese Studies. 20 (1). Routledge: 67–88. doi:10.1080/10371390050009075.

- ^ a b Takeuchi, Naoko (October 1999). Materials Collection. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-324521-7.

- ^ a b c Schodt, Frederik (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-880656-23-5.

- ^ a b Alverson, Brigid (2011-05-27). "Sailor Moon 101: Pretty, Powerful, And Pure Of Heart". MTV. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (October 23, 2003). "Punch!". Bishōjo Senshi Sailormoon Shinsouban Volume 3. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-334783-4.

- ^ a b Takeuchi, Naoko (2013). "Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon ~Ten Years of Love and Miracles~". Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon: Short Stories. Vol. 2. New York: Kodansha Comics USA. pp. 196–200. ISBN 978-1-612-62010-7.

- ^ "美少女戦士セーラームーン (1)" (in Japanese). Kodansha. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ^ "美少女戦士セーラームーン (18)" (in Japanese). Kodansha. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ^ a b Schodt, Frederik (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-880656-23-5.

- ^ "美少女戦士セーラームーン 新装版(1)" (in Japanese). Kodansha. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ^ Brad Stephenson (2012-01-23). "3rd Gen Japanese Sailor Moon Manga Shopping Guide". moonkitty.net. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- ^ a b by Elly (2013-10-10). "Sailor Moon Kanzenban + iPad Mini + Smart Phone Cases". Miss Dream. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- ^ a b "TV Asahi Top 100 Anime Part 2". Anime News Network. 2005-09-23. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ a b "Japan's Favorite TV Anime". Anime News Network. 2006-10-13. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ "『美少女戦士セーラームーン』が9月に一挙放送! 月野うさぎ役・三石琴乃さんの合同記者会見レポート!". ANIMAX. Archived from the original on 2011-09-12. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ a b "セーラームーンのあゆみ 1993年" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Retrieved 2009-07-21.[dead link]

- ^ "セーラームーンのあゆみ 1994年" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Archived from the original on 2009-04-25. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ "セーラームーンのあゆみ 1995年" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Archived from the original on 2011-03-13. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Sailor Moon staff information". Usagi.org. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ a b "Sailor Moon Manga Gets New Anime in Summer 2013". Anime News Network. July 6, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Zahed, Ramin (July 6, 2012). "New 'Sailor Moon' Reboot Arrives in 2013". Animation Magazine. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "New Sailor Moon Anime to Stream Worldwide This Winter". Anime News Network. 2013-08-04. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ "New Sailor Moon Anime Delayed - News". Anime News Network. 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ a b "New Sailor Moon Anime by Toei to Premiere in July - News". Anime News Network. 2014-01-09. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- ^ "Sailor Moon Website's Animation Page Opens a Countdown - News". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ "2014's New Sailor Moon Crystal Anime's 1st Image, Story Intro Posted Online - News". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (August 1994). Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon Volume I Original Picture Collection. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-324507-1.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (August 1994). Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon Volume II Original Picture Collection. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-324508-X.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (September 1996). Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon Volume III Original Picture Collection. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-324518-7.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (September 1996). Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon Volume IV Original Picture Collection. Kodansha. ISBN ISBN 4-06-324519-5.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (August 1997). Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon Volume V Original Picture Collection. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-324522-5.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (September 1999). Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon Materials Collection. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-324521-7.

- ^ "セーラームーン ビデオ・DVDコーナー" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Retrieved 2009-07-19.[dead link]

- ^ a b Font, Dillon (May 2004). "Sailor Soldiers, Saban Style". Animefringe. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ "これまでの公演の紹介 93サマースペシャルミュージカル 美少女戦士セーラームーン 外伝 ダーク・キングダム復活篇" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Retrieved 2009-07-21.[dead link]

- ^ "これまでの公演の紹介 94サマースペシャルミュージカル美少女戦士セーラームーンSうさぎ・愛の戦士への道" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Retrieved 2009-07-21.[dead link]

- ^ "95スプリングスペシャルミュージカル 美少女戦士セーラームーンS 変身・スーパー戦士への道(改訂版)" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Retrieved 2009-07-21.[dead link]

- ^ Lobão, David Denis (May 24, 2007). "Musicais do OhaYO! – Parte 2" (in Portuguese). Universo Online. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ "Osabu Twitter" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- ^ "Sailor Moon Chibi Trading Figures Scheduled for Early 2014". Crunchyroll. 2013-10-10. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- ^ "Sailormoon. Channel - History of Sailor Moon". Archived from the original on 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ "Sailormoon. Channel - Sailor Moon Live Action TV Corner". Archived from the original on 2007-06-17. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ a b Mays, Jonathon (April 6, 2004). "Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon - Review". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ "実写板DVD(TVシリーズ)" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.gamefaqs.com/search/index.html?game=sailor+moon&platform=0

- ^ "The 3D Adventures of Sailor Moon for PC". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "New Sailor Moon DS Game to Ship in Spring in Italy - Interest". Anime News Network. 2011-09-16. Retrieved 2011-09-20.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Jason (2007). Manga: The Complete Guide. New York: Ballantine Books & Del Rey Books. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-345-48590-8.

- ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=VHEVAAAAIBAJ&sjid=C-sDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6716,7966764&dq=sailor+moon+power+rangers

- ^ Arnold, Adam "OMEGA" (June 2001). "Sailor Moon à la Saban: Debunked - An Interview with Rocky Solotoff" (Q&A). Animefringe. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ "DIC Entertainment Corporate". DiC Entertainment. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=COcyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=vgcGAAAAIBAJ&pg=1971,3417888&dq=sailor+moon&hl=en

- ^ Sebert, Paul (2000-06-28). "Kissing cousins may bring controversy Cartoon Network juggles controversial topics contained in the "Sailor Moon S" series". The Daily Athenaeum Interactive. Archived from the original on 2007-03-29. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ^ "AnimeNation Anime News Blog » Blog Archive » Ask John: What's the Current Status of Sailor Moon in America?". Animenation.net. 2005-12-02. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "Mixx Controversies: Analysis". Features. Anime News Network. 2008-08-14. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ "Sailor Moon Volume 1". Mixx Entertainment. Archived from the original on November 7, 2004. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ "Sailor Moon StarS Volume 3". Mixx Entertainment. Archived from the original on November 10, 2004. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ "Tokyopop Out of Print". 2007-10-13. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ^ "Sailor Moon 1 by Naoko Takeuchi - Book". Random House. 2011-09-13. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ "Sailor Moon 1 by Naoko Takeuchi - Book". Random House. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ "Codename Sailor V 1 by Naoko Takeuchi - Book". Random House. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ "Sailor Moon Short Stories 1 by Naoko Takeuchi - Book". Random House. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ "Sailor Moon Short Stories 2 by Naoko Takeuchi - Book". Random House. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ "Takanori Arisawa Profile(E)". Arizm.com. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "/ セーラームーン". Toei-anim.co.jp. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "/ セーラームーン R". Toei-anim.co.jp. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "/ セーラームーン S". Toei-anim.co.jp. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "/ セーラームーン Supers". Toei-anim.co.jp. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "/ 美少女戦士セーラームーン セーラースターズ". Toei-anim.co.jp. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Ledoux, Trish (1996). The Complete Anime Guide: Japanese Animation Video Directory & Resource Guide. Tiger Mountain Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-9649542-3-6.

The American Sailor Moon even translated the Japanese show's signature opening song more or less intact, one of the few anime adaptations since Star Blazers to do so.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Whoosh! In the News: Babes in toyland; Xena versus Sailor Moon". Whoosh.org. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ^ "Crybaby Usagi's Magnificent Transformation". Sailor Moon. Episode 1. March 7, 1992. Toei. Asahi.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|seriesno=ignored (|series-number=suggested) (help) As translated in the licensed subtitled DVD release by ADV films. - ^ "A Moon Star is Born". Sailor Moon (English dub). Episode 1. September 11, 1995. DiC. YTV.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|seriesno=ignored (|series-number=suggested) (help) - ^ channel.or. jp/ayumi/1992.html "セーラームーンのあゆみ 1992年" (in Japanese). Sailormoon. Channel.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2009-02-28. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "第15回アニメグランプリ [1993年5月号]" (in Japanese). Animage.jp. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ "第16回アニメグランプリ [1994年5月号]" (in Japanese). Animage.jp. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ "第17回アニメグランプリ [1995年5月号]" (in Japanese). Animage.jp. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ "第18回アニメグランプリ [1996年5月号]" (in Japanese). Animage.jp. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ "第19回アニメグランプリ [1997年6月号]" (in Japanese). Animage.jp. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Joel Hahn. "Kodansha Manga Awards". Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Animazement Sailor Moon Voice Actors 2005". May 2005. Archived from the original on 2006-10-22. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ http://www.akadot.com/story.php?id=31[dead link]

- ^ "Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon TV episode guide". Usagi.org. 1994-12-22. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ a b c Penedo, Nicolas (2008). Nicolas Finet (ed.). Dicomanga: le dictionnaire encyclopédique de la bande dessinée japonaise (in French). Paris: Fleurus. p. 464. ISBN 978-2-215-07931-6.

- ^ a b Drazen, Patrick (October 2002). Anime Explosion! The What? Why? & Wow! Of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 1-880656-72-8. OCLC 50898281.

- ^ "ICv2 News - Sailor Moon Graphic Novels Top Bookstore Sales - Demonstrates Shoujo's Potential". ICv2. August 14, 2001. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ "MIXX'S SAILOR MOON MANGA IS THE NUMBER 1 GRAPHIC NOVEL OR TRADE PAPERBACK IN AMERICA!" Mixx Entertainment. June 18, 1999. Retrieved on August 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Allison, Anne (June 2000). "Sailor Moon: Japanese Superheroes for Global Girls". In Timothy J. Craig (ed.). Japan Pop!: Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. M. E. Sharpe. pp. 259–278. ISBN 978-0-7656-0561-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|origdate=(help) - ^ Allison, Anne (2006). Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. University of California Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-520-24565-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Poitras, Gilles (2000-12-01) Anime Essentials: Every Thing a Fan Needs to Know Stone Bridge Press, ISBN 1-880656-53-1 p.44

- ^ Cornog, Martha; and Perper, Timothy (March 2005) Non-Western Sexuality Comes to the U. S.: A Crash Course in Manga and Anime for Sexologists Contemporary Sexuality vol 39 issue 3 page 4

- ^ "Platonic Eros, Ottonian Numinous and Spiritual Longing in Otaku Culture" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ Bertschy, Zac (2003-08-10). "Sailor Moon DVD - Review". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- ^ Merrill, Dave (2006-01-17). "Sailor Moon Super S TV Series Complete Collection". Anime Jump. Archived from the original on May 10, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- ^ Drazen, Patrick (October 2002). Anime Explosion! The What? Why? & Wow! Of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 284. ISBN 1-880656-72-8. OCLC 50898281.

- ^ a b Cox, Gemma (Spring 2006). "Anime Archive: Sailor Moon - The Most Popular Unsuccessful Series Ever?". NEO (18). Uncooked Media: 98.

- ^ Clements, Jonathan (2001-09-01). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (1st ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 338. ISBN 1-880656-64-7. OCLC 47255331.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McHarry, Mark. Yaoi: Redrawing Male Love[dead link] The Guide November 2003

- ^ Seung Mi-Han (2001). "Learning from the enviable enemy: the coexistance of desire and enmity in Korean perceptions of Japan". Globalizing Japan: Ethnography of the Japanese Presence in Asia, Europe, and America. Routledge. p. 200.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sailor Moon - Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga". Anime News Network. 2011-03-03. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Durand, Sylvain (March–April 1996). "Sailor Moon: Manga vs Animation". Protoculture Addicts (39): 39.

- ^ Taylor, Ihsan. "Best Sellers - The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "New York Times Manga Best Seller List, September 11–17". Anime News Network. September 23, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "Kodansha: Sailor Moon 1 Reprinted after 50,000 Sell Out - News". Anime News Network. 2011-10-14. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ Thompson, Jason. Manga: The Complete Guide. p. 199.

- ^ a b Poitras, Gilles (2000-12-01) Anime Essentials: Every Thing a Fan Needs to Know Stone Bridge Press, ISBN 1-880656-53-1 pp.31-32

- ^ Sevakis, Justin (January 1, 1999). "Anime and Teen Culture... Uh-oh". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Alverson, Brigid (17 February 2009). "Matt Thorn Returns to Translation". Publishers Weekly. PWxyz, LLC. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ a b http://www.akadot.com/story.php?id=30[dead link]

- ^ Deppey, Dirk (2005). "She's Got Her Own Thing Now". The Comics Journal (269). Archived from the original on 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

Scratch a modern-day manga fangirl, and you're likely to find someone who watched Sailor Moon when she was young.

- ^ a b c d e Femspec - Young Females as Super Heroes: Superheroines in the Animated Sailor Moon

- ^ a b "The Toronto Star Archive". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. 1996-07-27. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ a b Drazen, Patrick (October 2002). Anime Explosion! The What? Why? & Wow! Of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 281. ISBN 1-880656-72-8. OCLC 50898281.

- ^ "Animerica: Animerica Feature: Separated at Birth? Buffy vs. Sailor Moon". Animerica. 2004-04-07. Archived from the original on 2004-04-07. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ "Animerica: Animerica Feature: Separated at Birth? Buffy vs. Sailor Moon". Animerica. 2004-04-07. Archived from the original on 2004-04-07. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ Yoshida, Kaori (2002). net/mcel. pacificu. edu/mcel. pacificu. edu/aspac/home/papers/scholars/yoshida/yoshida. php3 "Evolution of Female Heroes: Carnival Mode of Gender Representation in Anime". Western Washington University. Archived from the original on 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

{{cite journal}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Welker, James (2006) "Drawing Out Lesbians: Blurred Representations of Lesbian Desire in Shōjo Manga" in Subhash Chandra e. d., Lesbian Voices: Canada and the World: Theory, Literature, Cinema New Delhi: Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd ISBN 81-8424-075-9 p.177, 180.

- ^ JON MATSUMOTO (1996-06-19). "Fans Sending an SOS for 'Sailor' - Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "We're Playing Their Toons". washingtonpost.com. 2004-12-06. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ Cox, Gemma. "Neo Magazine - Article". Neomag.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ Updike, Edith (1997). "The Novice Who Tamed The Web". Business Week. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Allison, Anne (2001). "Cyborg Violence: Bursting Borders and Bodies with Queer Machines" (PDF). Cultural Anthropology. 16 (2): 237–265. doi:10.1525/can.2001.16.2.237. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ "Toei Shopping 'Sailor Moon' Anime". ICv2. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ ""Czarodziejka z Księżyca" powraca do polskiej telewizji".

- ^ "Worldwide 'Sailor Moon' Revival". ICv2. 2010-02-03. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Kodansha USA Announces the Return of Sailor Moon". Press release. 2011-03-18. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- ^ a b Takeuchi, Naoko (2009-09-09). "Sailor Moon, Vol. 2 (9781935429753): Naoko Takeuchi: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (2009-09-09). "Sailor Moon, Vol. 3 (9781935429760): Naoko Takeuchi: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (2009-09-09). "Sailor Moon, Vol. 4 (9781612620008): Naoko Takeuchi: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ "Kodansha Comics USA | Release Dates". Kodanshacomics.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Takeuchi, Naoko (2009-09-09). "Codename: Sailor V, Vol. 2 (9781935429784): Naoko Takeuchi: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

External links

- Official Sailormoon website Template:Ja icon

- Official Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon 20th anniversary project website Template:Ja icon

- Sailor Moon (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Sailor Moon at Curlie

- Manga series

- 1992 manga

- 1992 anime television series debuts

- 1993 anime television series debuts

- 1994 anime television series debuts

- 1995 anime television series debuts

- 1996 anime television series debuts

- 2014 anime television series debuts

- Sailor Moon

- 1992 anime television series

- 1993 anime television series

- 1994 anime television series

- 1995 anime television series

- 1996 anime television series

- 2014 anime television series

- ADV Films

- Television series by DIC Entertainment

- Japanese LGBT-related television programs

- Comedy-drama anime and manga

- Magical girl anime and manga

- Romance anime and manga

- Science fantasy anime and manga

- Shōjo manga

- Television series about the Moon

- Toei Animation

- Tokyopop titles

- Toonami

- TV Asahi shows

- Winner of Kodansha Manga Award (Shōjo)

- Cartoon Network programs

- Upcoming television series

- English-language television programming

- Jetix

- Programs acquired by ABS-CBN