Coriander

| Coriander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. sativum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Coriandrum sativum | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 95 kJ (23 kcal) |

3.67 g | |

| Sugars | 0.87 |

| Dietary fiber | 2.8 g |

0.52 g | |

2.13 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 37% 337 μg36% 3930 μg865 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 6% 0.067 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 12% 0.162 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 7% 1.114 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 11% 0.57 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 9% 0.149 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 16% 62 μg |

| Vitamin C | 30% 27 mg |

| Vitamin E | 17% 2.5 mg |

| Vitamin K | 258% 310 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 5% 67 mg |

| Iron | 10% 1.77 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 26 mg |

| Manganese | 19% 0.426 mg |

| Phosphorus | 4% 48 mg |

| Potassium | 17% 521 mg |

| Sodium | 2% 46 mg |

| Zinc | 5% 0.5 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 92.21 g |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[1] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[2] | |

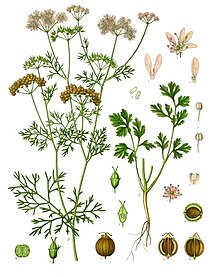

Coriander (Coriandrum sativum), also known as cilantro, Chinese parsley or dhania,[3] is an annual herb in the family Apiaceae. Coriander is native to regions spanning from southern Europe and North Africa to southwestern Asia. It is a soft plant growing to 50 cm (20 in) tall. The leaves are variable in shape, broadly lobed at the base of the plant, and slender and feathery higher on the flowering stems. The flowers are borne in small umbels, white or very pale pink, asymmetrical, with the petals pointing away from the centre of the umbel longer (5–6 mm or 0.20–0.24 in) than those pointing toward it (only 1–3 mm or 0.039–0.118 in long). The fruit is a globular, dry schizocarp 3–5 mm (0.12–0.20 in) in diameter. Although sometimes eaten alone, the seeds often are used as a spice or an added ingredient in other foods.

Etymology

First attested in English late fourteenth century, the word coriander derives from the Old French: coriandre, which comes from Latin: coriandrum,[4] in turn from [κορίαννον koriannon] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help).[5][6] The earliest attested form of the word is the Mycenaean Greek 𐀒𐀪𐀊𐀅𐀙 ko-ri-ja-da-na[7] (written in Linear B syllabic script, reconstructed as koriadnon), similar to the name of Minos's daughter Ariadne, which later evolved to koriannon or koriandron.[8]

Cilantro is the Spanish word for coriander, also deriving from coriandrum. It is the common term in North America for coriander leaves, due to their extensive use in Mexican cuisine.

Uses

All parts of the plant are edible, but the fresh leaves and the dried seeds are the parts most traditionally used in cooking. Coriander is common in South Asian, Southeast Asian, Indian, Middle Eastern, Caucasian,[9][10] Central Asian, Mediterranean, Tex-Mex, Latin American, Portuguese, Chinese, African, and Scandinavian cuisine.[11][12]

Leaves

The leaves are variously referred to as coriander leaves, fresh coriander, Chinese parsley, or (in North America) cilantro.

It should not be confused with culantro (Eryngium foetidum L.) which is a close relative to coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) but has a distinctly different appearance, a much more potent volatile leaf oil[13] and a stronger smell.

The leaves have a different taste from the seeds, with citrus overtones. However, many people experience an unpleasant soapy taste or a rank smell and avoid the leaves.[14][15][16] The flavours have also been compared to those of the stink bug, and similar chemical groups are involved (aldehydes). The different perceptions of the coriander leaves' taste is likely genetic, with some people having no response to the aromatic chemical that most find pleasant, while simultaneously being sensitive to certain offending unsaturated aldehydes.[17]

The fresh leaves are an ingredient in many Indian foods (such as chutneys and salads), in Chinese and Thai dishes, in Mexican cooking, particularly in salsa and guacamole and as a garnish, and in salads in Russia and other CIS countries. Chopped coriander leaves are a garnish on Indian dishes such as dal. As heat diminishes their flavour, coriander leaves are often used raw or added to the dish immediately before serving. In Indian and Central Asian recipes, coriander leaves are used in large amounts and cooked until the flavour diminishes.[18] The leaves spoil quickly when removed from the plant, and lose their aroma when dried or frozen.

Fruits

The dry fruits are known as coriander seeds. In Indian cuisine they are called dhania.[19][20]

The word coriander in food preparation may refer solely to these seeds (as a spice), rather than to the plant. The seeds have a lemony citrus flavour when crushed, due to terpenes linalool and pinene. It is described as warm, nutty, spicy, and orange-flavoured.

The nutritional profile of coriander seed is different from the fresh stems and leaves, the vitamin content being less than amounts being displayed in the chart above for the plant, with some being absent entirely. However, the seeds do provide significant amounts of calcium, iron, magnesium, and manganese.[21]

The variety C. s. vulgare has a fruit diameter of 3–5 mm (0.12–0.20 in), while var. microcarpum fruits have a diameter of 1.5–3 mm (0.059–0.118 in). Large-fruited types are grown mainly by tropical and subtropical countries, e.g. Morocco, India and Australia, and contain a low volatile oil content (0.1-0.4%). They are used extensively for grinding and blending purposes in the spice trade. Types with smaller fruit are produced in temperate regions and usually have a volatile oil content of around 0.4-1.8%, so are highly valued as a raw material for the preparation of essential oil.[22]

It is commonly found both as whole dried seeds and in ground form. Seeds can be roasted or heated on a dry pan briefly before grinding to enhance and alter the aroma. Ground coriander seed loses flavour quickly in storage and is best ground fresh.

Coriander seed is a spice in garam masala and Indian curries, which often employ the ground fruits in generous amounts together with cumin. It acts as a thickener.

Roasted coriander seeds, called dhana dal, are eaten as a snack. They are the main ingredient of the two south Indian dishes: sambhar and rasam. Coriander seeds are boiled with water and drunk as indigenous medicine for colds.

Outside of Asia, coriander seed is used widely in the process for pickling vegetables. In Germany and South Africa (see boerewors) the seeds are used while making sausages. In Russia and Central Europe, coriander seed is an occasional ingredient in rye bread (e.g. borodinsky bread), as an alternative to caraway. Coriander seeds are used in European cuisine today, though they were more important in former centuries.[citation needed]

The Zuni people have adapted it into their cuisine, mixing the powdered seeds ground with chile and using it as a condiment with meat, and eating leaves as a salad.[23]

Coriander seeds are used in brewing certain styles of beer, particularly some Belgian wheat beers.[24] The coriander seeds are used with orange peel to add a citrus character.

Roots

Coriander roots have a deeper, more intense flavour than the leaves. They are used in a variety of Asian cuisines. They are commonly used in Thai dishes, including soups and curry pastes.

History

Coriander grows wild over a wide area of the Near East and southern Europe, prompting the comment, "It is hard to define exactly where this plant is wild and where it only recently established itself."[25] Fifteen desiccated mericarps were found in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B level of the Nahal Hemel Cave in Israel, which may be the oldest archaeological find of coriander. About half a litre of coriander mericarps were recovered from the tomb of Tutankhamen, and because this plant does not grow wild in Egypt, Zohary and Hopf interpret this find as proof that coriander was cultivated by the ancient Egyptians.[25]

Coriander seems to have been cultivated in Greece since at least the second millennium BC. One of the Linear B tablets recovered from Pylos refers to the species as being cultivated for the manufacture of perfumes, and it appears that it was used in two forms: as a spice for its seeds and as a herb for the flavour of its leaves.[8] This appears to be confirmed by archaeological evidence from the same period: the large quantities of the species retrieved from an Early Bronze Age layer at Sitagroi in Macedonia could point to cultivation of the species at that time.[26]

Coriander was brought to the British colonies in North America in 1670, and was one of the first spices cultivated by early settlers.[citation needed]

Similar plants

Other herbs are used where they grow in much the same way as coriander leaves.

- Eryngium foetidum has a similar, but more intense, taste. It is known as culantro, and is found in Mexico, South America and the Caribbean.[27]

- Persicaria odorata is commonly called Vietnamese coriander, or rau răm. The leaves have a similar odour and flavour to coriander. It is a member of the Polygonaceae, or buckwheat family.[27]

- Papaloquelite is one common name for Porophyllum ruderale subsp. macrocephalum, a member of the Compositae or Asteraceae, the sunflower family. This species is found growing wild from Texas to Argentina.[27]

Health effects and medicinal uses

Coriander, like many spices, contains antioxidants, which can delay or prevent the spoilage of food seasoned with this spice. A study found both the leaves and seed to contain antioxidants, but the leaves were found to have a stronger effect.[28]

Chemicals derived from coriander leaves were found to have antibacterial activity against Salmonella choleraesuis, and this activity was found to be caused in part by these chemicals acting as nonionic surfactants.[29]

Coriander has been documented as a traditional treatment for type 2 diabetes.[30] A study on mice found coriander extract had both insulin-releasing and insulin-like activity.[31]

Coriander seeds were found in a study on rats to have a significant hypolipidaemic effect, resulting in lowering of levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides, and increasing levels of high-density lipoprotein. This effect appeared to be caused by increasing synthesis of bile by the liver and increasing the breakdown of cholesterol into other compounds.[32]

Coriander leaf was found to prevent deposition of lead in mice, due to a presumptive chelation of lead by substances in the plant.[33]

Coriander can produce an allergic reaction in some people.[34][35][36]

The essential oil produced from Coriandrum sativum has been shown to exhibit antimicrobial effects.[37]

References

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

- ^ "dhania". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis. "coriandrum". A Latin Dictionary.

- ^ Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott. "κορίαννον". A Greek-English Lexicon.

- ^ "Coriander", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Edition, 1989. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "The Linear B word ko-ri-ja-da-na". Palaeolexicon.

- ^ a b Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge University Press. p. 119.

- ^ "кориандр". Кулинарный словарь (Culinary Dictionary) (in Russian). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ "Кориандр посевной (кинза)". Букварь здоровья (The ABC of Health) (in Russian). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ "Cooking ingredients: Spices".

- ^ Samuelsson, Marcus (2003). Aquavit: And the New Scandinavian Cuisine. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 12 (of 312). ISBN 0618109412.

- ^ Ramcharan, C. (1999). J. Janick (ed.). "Perspectives on new crops and new uses". ASHS Press: 506–509.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ McGee, Harold (13 April 2010). "Cilantro Haters, It's Not Your Fault". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

Some people may be genetically predisposed to dislike cilantro, according to often-cited studies by Charles J. Wysocki of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia.

- ^ Rubenstein, Sarah (13 February 2009). "Across the Land, People Are Fuming Over an Herb (No, Not That One)". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Website devoted to those finding cilantro offensive

- ^ NPR story about how people taste cilantro/coriander (December 2008)

- ^ Gernot Katzer. "Coriander Seeds and Cilantro Herb". Spice Pages.

- ^ "dhania". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "coriander". Tarladala.com.

- ^ Nutritional Data, coriander seed spice, nutritionaldata.self.com, accessed 2013.08.10

- ^ Bruce Smallfield (June 1993). "Coriander - Coriandrum sativum". Archived from the original on 4 April 2004.

- ^ Stevenson, Matilda Coxe 1915 Ethnobotany of the Zuni Indians. SI-BAE Annual Report #30 (p. 66)

- ^ [1] Wheat Beers

- ^ a b Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of plants in the Old World, third edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 205–206

- ^ Fragiska, M. (2005). "Wild and Cultivated Vegetables, Herbs and Spices in Greek Antiquity". Environmental Archaeology. 10 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1179/146141005790083858.

- ^ a b c Tucker, A.O.; DeBaggio, T. (1992). "Cilantro Around The World". Herb Conpanion. 4 (4): 36–41.

- ^ Wangensteen, Helle; Samuelsen, Anne Berit; Malterud, Karl Egil (2004). "Antioxidant activity in extracts from coriander". Food Chemistry. 88 (2): 293. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.01.047.

- ^ Kubo, Isao; Fujita, Ken-Ichi; Kubo, Aya; Nihei, Ken-Ichi; Ogura, Tetsuya (2004). "Antibacterial Activity of Coriander Volatile Compounds againstSalmonella choleraesuis". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (11): 3329–32. doi:10.1021/jf0354186. PMID 15161192.

- ^ Eidi, M; Eidi, A; Saeidi, A; Molanaei, S; Sadeghipour, A; Bahar, M; Bahar, K (2009). "Effect of coriander seed (Coriandrum sativum L.) ethanol extract on insulin release from pancreatic beta cells in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats". Phytotherapy Research. 23 (3): 404–6. doi:10.1002/ptr.2642. PMID 19003941.

- ^ Gray, Alison M.; Flatt, Peter R. (2007). "Insulin-releasing and insulin-like activity of the traditional anti-diabetic plant Coriandrum sativum (coriander)". British Journal of Nutrition. 81 (3): 203–9. doi:10.1017/S0007114599000392. PMID 10434846.

- ^ Chithra, V.; Leelamma, S. (1997). "Hypolipidemic effect of coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum): Mechanism of action". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 51 (2): 167–72. doi:10.1023/A:1007975430328. PMID 9527351.

- ^ Aga, M; Iwaki, K; Ueda, Y; Ushio, S; Masaki, N; Fukuda, S; Kimoto, T; Ikeda, M; Kurimoto, M (2001). "Preventive effect of Coriandrum sativum (Chinese parsley) on localized lead deposition in ICR mice". Journal of ethnopharmacology. 77 (2–3): 203–8. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00299-9. PMID 11535365.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Ebo, DG; Bridts, CH; Mertens, MH; Stevens, WJ (2006). "Coriander anaphylaxis in a spice grinder with undetected occupational allergy". Acta clinica Belgica. 61 (3): 152–6. PMID 16881566. INIST 17926832.

- ^ Suhonen, Raimo; Keskinen, Helena; Björkstén, Fred; Vaheri, Eero; Zitting, Antti (2007). "Allergy to Coriander a Case Report". Allergy. 34 (5): 327–30. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1979.tb04374.x. PMID 546248.

- ^ "Food Allergy - Coriander Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatments and Causes". RightDiagnosis.com. 1 February 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Duman, AD; Telci, I; Dayisoylu, KS; Digrak, M; Demirtas, I; Alma, MH (2010). "Evaluation of bioactivity of linalool-rich essential oils from Ocimum basilucum and Coriandrum sativum varieties". Natural product communications. 5 (6): 969–74. PMID 20614837.

Further reading

- Katzer, Gernot Coriander Seeds and Cilantro (Coriandrum sativum)

- Noxon, Heather and Meyer, Alex (2004). Genetic Analysis of PTC and Cilantro Taste Preferences. MindExpo 2004

- Knaapila, A.; Hwang, L.-D.; Lysenko, A.; Duke, F. F.; Fesi, B.; Khoshnevisan, A.; James, R. S.; Wysocki, C. J.; Rhyu, M.; Tordoff, M. G.; Bachmanov, A. A.; Mura, E.; Nagai, H.; Reed, D. R. (2012). "Genetic Analysis of Chemosensory Traits in Human Twins". Chemical Senses. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjs070.