Immigration to Australia

Parts of this article (those related to the effects of Australian government new policy in the last few years concerning illegal immigration. About all numerical data and assessments of the policy stop around 2013.) need to be updated. (September 2015) |

Immigration to Australia is considered part of the history of human migration that started in Africa.[1] It is estimated that first humans arrived in Australia approximately 50,000 years ago[2][3] when ancestors of the first wave of migrants from Africa arrived on the continent via the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia and New Guinea. European colonisation commenced in 1788 with British colonisation. Immigration, the process of arriving in another country in order to stay,[4] continued after the Federation of the British Australian colonies in 1901.

Since 1945, more than 7 million people have settled in Australia. The trigger for a large-scale immigration program was the end of World War II. Agreements were reached with Britain, some European countries and with the International Refugee Organization to encourage immigration, including people displaced by the war in Europe. The highest number of settlers to arrive in any one year since World War II was 185,099 in 1969–70. The lowest number in any one year was 52,752 in 1975–76. Approximately 1.6 million migrants arrived between October 1945 and 30 June 1960, about 1.3 million in the 1960s, about 960,000 in the 1970s, about 1.1 million in the 1980s, over 900,000 in the 1990s, about 1.8 million in the 2000s, and nearly 1 million since the year 2010.[5]

Australia’s migrant population has historically been largely from a European background, with the largest source now being Asian migrants.[6]

Net overseas migration increased from 30,042 in 1992–93[7] to 212,700 persons in 2013–14.[8] The largest components of immigration are the skilled migration and family re-union programs. In recent years the mandatory detention of unauthorised arrivals by boat has generated great levels of controversy. However, a 2014 sociological study concluded that: "Australia and Canada are the most receptive to immigration among western nations".[9] The 2011 census reported that over one in four of Australia's 22 million people were born overseas. For the decade up to 2013, most migrants were born in New Zealand (14.3%), India (13.1%), the United Kingdom (12.7%), China (11.4%) and the Philippines (4.4%).[10]

According to the Graduate Careers Survey,[11] full-time employment for newly qualified professionals from various occupations has declined since 2011.[12] The professional associations of some of these occupations have expressed their criticism of the immigration policy.[13]

Immigration history of Australia

The first migration of humans to the continent took place around 50,000 years ago via the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea as part of the early history of human migration out of Africa.[1]

Penal transportation

European migration to Australia began with the British convict settlement of Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788. The First Fleet comprised 11 ships carrying 775 convicts and 645 officials, members of the crew, marines, and their families and children. The settlers consisted of petty criminals, second-rate soldiers and a crew of sailors. There were few with skills needed to start a self-sufficient settlement, such as farmers and builders, and the colony experienced hunger and hardships. Male settlers far outnumbered female settlers. The Second Fleet arrived in 1790 bringing more convicts. The conditions of the transportation was described as horrific and as worse than slave transports. Of the 1,026 convicts who embarked, 267 (256 men and 11 women) died during the voyage (26%); a further 486 were sick when they arrived of which 124 died soon after. The fleet was more of a drain on the struggling settlement than of any benefit. Conditions on the Third Fleet, which followed on the heels of the Second Fleet in 1791, were a bit better. The fleet comprised 11 ships. Of the more than 2000 convicts brought onto the ships, 173 male convicts and 9 female convicts died during the voyage. Other transport fleets bringing further convicts as well as freemen to the colony would follow. By the end of the penal transportation in 1868, approximately 165,000 people had entered Australia as convicts.[14]

Gold rush and population growth

The Gold rush era, beginning in 1851, led to an enormous expansion in population, including large numbers of British and Irish settlers, followed by smaller numbers of Germans and other Europeans, and Chinese. This latter group were subject to increasing restrictions and discrimination, making it impossible for many to remain in the country. With the Federation of the Australian colonies into a single nation, one of the first acts of the new Commonwealth Government was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, otherwise known as the White Australia policy, which was a strengthening and unification of disparate colonial policies designed to restrict non-White settlement. Because of opposition from the British government, an explicit racial policy was avoided in the legislation, with the control mechanism being a dictation test in a European language selected by the immigration officer. This was selected to be one the immigrant did not know; the last time an immigrant passed a test was in 1909. Perhaps the most celebrated case was Egon Erwin Kisch, a left-wing Czechoslovakian journalist, who could speak five languages, who was failed in a test in Scottish Gaelic, and deported as illiterate.

The government also found that if it wanted immigrants it had to subsidise migration. The great distance from Europe made Australia a more expensive and less attractive destination than Canada and the United States. The number of immigrants needed during different stages of the economic cycle could be controlled by varying the subsidy. Before federation in 1901, assisted migrants received passage assistance from colonial government funds. The British government paid for the passage of convicts, paupers, the military and civil servants. Few immigrants received colonial government assistance before 1831.[15]

| Period | Annual average assisted immigrants[15] |

|---|---|

| 1831–1860 | 18,268 |

| 1861–1900 | 10,087 |

| 1901–1940 | 10,662 |

| 1941–1980 | 52,960 |

With the onset of the Great Depression, the Governor-General proclaimed the cessation of immigration until further notice, and the next group to arrive were 5000 Jewish refuge families from Germany in 1938. Approved groups such as these were assured of entry by being issued with a Certificate of Exemption from the Dictation Test.

Post-war immigration to Australia

After World War II Australia launched a massive immigration program, believing that having narrowly avoided a Japanese invasion, Australia must "populate or perish". Hundreds of thousands of displaced Europeans migrated to Australia and over 1,000,000 British subjects immigrated under the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme, colloquially becoming known as Ten Pound Poms.[16] The scheme initially targeted citizens of all Commonwealth countries; after the war it gradually extended to other countries such as the Netherlands and Italy. The qualifications were straightforward: migrants needed to be in sound health and under the age of 45 years. There were initially no skill restrictions, although under the White Australia Policy, people from mixed-race backgrounds found it very difficult to take advantage of the scheme.[17]

In the 1970s, multiculturalism largely displaced cultural selectivity in immigration policy.

Current government immigration programs

Migration program

There are a number of different types of Australian immigration, classed under different categories of visa:

- Employment visas

- Australian working visas are most commonly granted to highly skilled workers. Candidates are assessed against a points-based system, granting points for certain standards of education. These types of visas are often sponsored by individual states, which recruit workers according to specific needs. Visas may also be granted to applicants sponsored by an Australian business. The most popular form of sponsored working visa is the 457 visa.[citation needed]

- Student visas

- The Australian Government actively encourages foreign students to study in Australia. There are a number of categories of student visa, most of which require a confirmed offer from an educational institution.

- Family visas

- Visas are often granted on the basis of family ties in Australia. There are a number of different types of Australian family visas, including Contributory Parent visas and Spouse visas.

- Skilled Visas

- A new[when?] electronic process for managing Australia's Skilled Migration Program. Intending migrants without an Employer Sponsor will need to complete an "Expression of Interest" (EOI), then based on the information provided, will be allocated a score against the points test. Skill Select will then rank intending migrants scores against other EOI's. - Those with the highest-ranking scores across a range of occupations may then be invited to apply for a Skilled Visa.[18]

Employment and family visas can often lead to Australian citizenship; however, this requires the applicant to have lived in Australia for at least four years with at least one year as a permanent resident.[19]

Humanitarian program

- Refugee

- "for people who are subject to persecution in their home country, who are typically outside their home country, and are in need of resettlement. The majority of applicants who are considered under this category are identified and referred by UNHCR to Australia for resettlement. The Refugee category includes the Refugee, In-country Special Humanitarian, Emergency Rescue and Woman at Risk visa subclasses."

- Special Humanitarian Program (SHP)

- "for people outside their home country who are subject to substantial discrimination amounting to gross violation of human rights in their home country, and immediate family of persons who have been granted protection in Australia. Applications for entry under the SHP must be supported by a proposer who is an Australian citizen, permanent resident or eligible New Zealand citizen, or an organisation that is based in Australia."[20]

The Humanitarian program for 2012–13 is set at 20,000 places, an increase of 6,250 from the previous year. This category includes a 12 per cent target for Woman at Risk visas. This allocation also includes Onshore Protection visas granted to people who apply for protection in Australia and are found to be refugees.[21] In 2010–11, a total of 13,799 visas were granted under the Humanitarian Program. A total of 5,998 visas were granted under the offshore component, including 759 Woman at Risk visas. In addition, 2,973 Special Humanitarian Program visas were granted to people outside Australia. A total of 4,828 visas were granted to people in Australia.[22]

Migration agents

It is possible to employ migration agents to assist with a visa application to Australia. Such persons who provide immigration assistance are regulated by a governing authority called the Office of the Migration Agents Registration Authority. Only Australian Citizens, Australian Permanent Residents, and New Zealand Citizens in Australia are eligible to apply to MARA for registration. Australian lawyers are immediately eligible to apply for registration whilst other applicants must hold a Graduate Certificate in Migration Law and Practice. Although, lawyers only make up a small number of registered Migration Agents, since 1998 more than 18 percent of the MARA’s sanction decisions have been against lawyer agents. The Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) strongly recommends that applicants considering using an agent should employ the services of a registered migration agent.[23]

The Australian Migration Profession has two peak professional associations, Migration Alliance and the MIA.

In February 2009, former Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, Senator Chris Evans, announced the establishment of a new body to regulate migration agents after a review found dissatisfaction among consumers and potential conflicts of interest under the existing arrangements.

Senator Evans said that from 1 July, the new Office of Migration Agents Registration Authority (MARA) will undertake the regulatory functions which have been operated under statutory self-regulation by the Migration Institute of Australia (MIA) since 1998.[24]

Migration and settlement services

The Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) is the Australian Government's largest settlement program. The AMEP is available to eligible migrants, from the humanitarian, family and skilled visa streams. Free English language courses are available to eligible migrants who do not have functional English. All AMEP clients have access to up to 510 hours of English language courses, in their first five years of settlement in Australia.

There are a variety of community-based services that cater to the needs of newly arrived migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, some of which receive funding from the Commonwealth Government, such as Migrant Resource Centres. The Department of Immigration and Citizenship also operates a 24-hour, seven days a week telephone interpreting service called the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS) National, which facilitates contact between non-English speakers and interpreters, enabling access to government and community services.

The Settlement Grants Program (SGP), provides funding to assist humanitarian entrants and migrants settle in Australia and participate equitably in Australian society as soon as possible after arrival. The SGP is targeted to deliver settlement services to humanitarian entrants, family migrants with low levels of English proficiency and dependants of skilled migrants in rural and regional areas with low English proficiency.

The Australian Cultural Orientation (AUSCO) program is provided to refugee and humanitarian visa holders who are preparing to settle in Australia. The program provides practical advice and the opportunity to ask questions about travel to and life in Australia. It is delivered overseas, before they begin their journey. The program is the beginning of the settlement process for people coming to Australia under the Humanitarian Program. AUSCO is available to all refugee and humanitarian visa holders over the age of five. The course is delivered over five days to ensure that all topics are covered in sufficient detail. From the beginning of the program in 2003 to the end of December 2010, more than 2100 courses have been conducted in Bangladesh, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, India, Iran, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Romania, the Republic of Congo, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Syria, Tanzania, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe and Afghanistan, assisting more than 39 000 people. Refugee and humanitarian visa holders are also eligible to receive on arrival settlement support through the Humanitarian Settlement Services (HSS) program, which provides intensive settlement support and equips individuals with the skills and knowledge to independently access services beyond the initial settlement period.

The Immigration Advice and Application Assistance Scheme provides professional assistance, free of charge, to disadvantaged visa applicants, to help with the completion and submission of visa applications, liaison with the department, and advice on complex immigration matters. It also provides migration advice to prospective visa applicants and sponsors.

In response to the needs of asylum seekers, the Asylum Seeker Assistance Scheme (ASAS) was created in 1992 to address Australia’s obligations under the United Nations 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. ASAS is administered by the Australian Red Cross under contract to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. ASAS provides financial assistance to asylum seekers in the community who satisfy specific eligibility criteria, and also facilitates access to casework assistance and other support services for asylum seekers through the Australian Red Cross.[25]

More recently, in 2009, Migration Alliance, a not-for-profit organisation was established to connect migrants with migration agents and settlement services via an online Australian immigration portal.

Country of birth of Australian residents

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics[27] in mid-2010 5,993,945 of the Australian resident population were born outside Australia, representing 26.8 percent of the total Australian resident population.

By 2050, it is estimated that approximately one-third of Australia's population could be born overseas.[28]

Australia and Switzerland, with about a quarter of their population born outside the country, are the two countries with the highest proportion of immigrants in the western world.[29]

| Top 40 Countries of birth | Estimated resident population(2006)[26] | Estimated resident population(2010)[27] | Estimated resident population(2015)[30] |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 1,153,264 | 1,192,878 | 1,207,000 |

| New Zealand | 476,719 | 544,171 | 611,400 |

| China | 203,143 | 379,776 | 481,800 |

| India | 153,579 | 340,604 | 432,700 |

| Italy | 220,469 | 216,303 | 198 200 |

| Vietnam | 180,352 | 210,803 | 230,200 |

| Philippines | 135,619 | 177,389 | 236,400 |

| South Africa | 118,816 | 155,692 | 178,700 |

| Malaysia | 103,947 | 135,607 | 156,500 |

| Germany | 114,921 | 128,558 | 125,900 |

| Greece | 125,849 | 127,195 | |

| South Korea | 49,141 | 100,255 | |

| Sri Lanka | 70,908 | 92,243 | |

| Lebanon | 86,599 | 90,395 | |

| Hong Kong | 76,303 | 90,295 | |

| Netherlands | 86,950 | 88,609 | |

| United States | 64,832 | 83,996 | |

| Indonesia | 67,952 | 73,527 | |

| Ireland | 57,338 | 72,378 | |

| Croatia | 56,540 | 68,319 | |

| Fiji | 58,815 | 62,778 | |

| Singapore | 49,819 | 58 903 | |

| Poland | 59,221 | 58,447 | |

| Thailand | 32,747 | 53,393 | |

| Japan | 29,469 | 52,111 | |

| Macedonia | 48,577 | 49,704 | |

| Malta | 48,978 | 48,870 | |

| Iraq | 40,400 | 48,348 | |

| Canada | 33,198 | 44,118 | |

| Serbia and Montenegro | 68,879 | 42,064 | |

| Egypt | 38,782 | 41,163 | |

| Turkey | 37,556 | 39,989 | |

| Taiwan | 31,258 | 38,025 | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 27,328 | 37,470 | |

| Iran | 25,659 | 33,696 | |

| Zimbabwe | 21,142 | 31,779 | |

| Cambodia | 28,175 | 31,397 | |

| Pakistan | 19,768 | 31,277 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 26,302 | 31,225 | |

| France | 20,054 | 30,631 | |

| Romania | 14,500 | 18,320 |

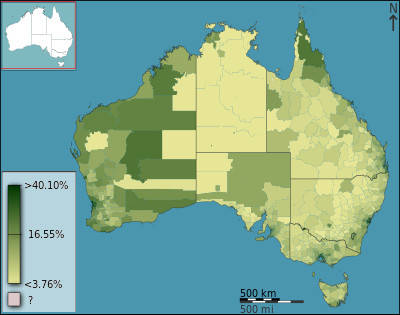

Settlement patterns

There are some differences in settlement patterns, as demonstrated in the statistics compiled at the 2006 Census.[31]

New South Wales has the largest population, and the largest foreign born population, in Australia (1,544,023). Certain nationalities are highly concentrated in this state: 74.5% of Lebanese-born, 63.1% of Iraqi-born, 63.0% of South Korean-born, 59.4% of Fijian-born and 59.4% of Chinese-born Australian residents live in New South Wales.

Victoria, the second most populous state, also has the second largest number of overseas-born persons (1,161,984). 50.6% of Sri Lankan-born, 50.1% of Turkish-born, 49.4% of Greek-born and 41.6% of Italian-born Australian residents were enumerated in this state.

Western Australia, with 528,827 overseas-born residents has the highest proportion of its population being foreign-born. The state attracts 29.6% of all Singapore-born Australian residents, and is narrowly behind New South Wales in having the largest population of British-born.

Queensland had 695,525 overseas-born residents, and attracted the greatest proportion of persons born in Papua New Guinea (52.4%) and New Zealand (38.2%).

Impacts and concerns

There is a wide range of views in the Australian community on the composition and level of immigration, and on the possible effects of varying the level of immigration and population growth, some of which are based on empirical data, others more speculative in nature. In 2002, a CSIRO population study entitled "Future Dilemmas", commissioned by the former Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, outlined six potential dilemmas associated with immigration-driven population growth. These dilemmas included the absolute numbers of aged continuing to rise despite high immigration off-setting ageing and declining birth-rates in a proportional sense, a worsening of Australia's trade balance due to more imports and higher consumption of domestic production, increased greenhouse gas emissions, overuse of agricultural soils, marine fisheries and domestic supplies of oil and gas, and a decline in urban air quality, river quality and biodiversity.[32]

Environment

Environmental movements, notably the organisation Sustainable Population Australia (SPA), believe that as the driest inhabited continent, Australia cannot continue to sustain its current rate of population growth without becoming overpopulated. SPA also argues that climate change will lead to a deterioration of natural ecosystems through increased temperatures, extreme weather events and less rainfall in the southern part of the continent, thus reducing its capacity to sustain a large population even further.[33] The UK-based Population Matters, (formerly known as the Optimum Population Trust), supports the view that Australia is overpopulated, and believes that to maintain the current standard of living in Australia, the optimum population is 10 million (rather than the then present 24 million), or 21 million with a reduced standard of living.[34]

It is argued that immigration exacerbates climate change, because immigrants generally come from countries with low greenhouse gas emissions per capita to countries with high per capita emissions (like Australia). A number of climate-change observers see population control as essential to arresting global warming.[35] Australia could experience more severe droughts and they could become more frequent in the future, a government-commissioned report said on 6 July 2008.[36] The Australian of the Year 2007, environmentalist Tim Flannery, predicted that unless it made drastic changes, Perth in Western Australia could become the world’s first ghost metropolis, an abandoned city with no more water to sustain its population.[37] This prediction has been labelled as "far-fetched" by some, considering Rottnest Island was "receiving its highest recorded rainfall figure for July".[38] Analysis by The Australia Institute shows that Australia’s population growth has been one of the main factors driving growth in domestic greenhouse gas emissions. It further finds that the average emissions per capita in the countries that immigrants come from is only 42 percent of average emissions in Australia, meaning that as immigrants alter their lifestyle to that of Australians, they increase global greenhouse gas emissions.[39] It is calculated that each additional 70,000 immigrants will lead to additional emissions of 20 million tonnes of greenhouse gases by the end of the Kyoto target period (2012) and 30 million tonnes by 2020.[40]

A correspondence published on the science journal, Nature, propose that wealthy countries should absorb climate-change migrants since the sending countries do not have the means to protect themselves against the impacts of climate change and the wealthy countries are largely responsible for the greenhouse gases accumulated in the atmosphere. The sending countries could include countries that are restricted to small islands and would not be able to return to their islands if sea levels rises due to climate change. However, the correspondence does state that the number of migrants that would be absorbed to each receiving country would be in proportion to the cumulative greenhouse gases that the receiving country is responsible for. Numbers as high as 750,000 could be absorbed by the United States while the Czech Republic could have numbers to the thousands.[41]

Housing

A number of economists, such as Macquarie Bank analyst Rory Robertson, assert that high immigration and the propensity of new arrivals to cluster in the capital cities is exacerbating the nation's housing affordability problem.[42] According to Robertson, Federal Government policies that fuel demand for housing, such as the currently high levels of immigration, as well as capital gains tax discounts and subsidies to boost fertility, have had a greater impact on housing affordability than land release on urban fringes.[43]

The Productivity Commission Inquiry Report No. 28 First Home Ownership (2004) also stated, in relation to housing, "that Growth in immigration since the mid-1990s has been an important contributor to underlying demand, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne."[44] This has been exacerbated by Australian lenders relaxing credit guidelines for temporary residents, allowing them to buy a home with a 10 percent deposit.

The RBA in its submission to the same PC Report also stated "rapid growth in overseas visitors such as students may have boosted demand for rental housing".[44] However, in question in the report was the statistical coverage of resident population. The "ABS population growth figures omit certain household formation groups – namely, overseas students and business migrants who do not continuously stay for 12 months in Australia."[44] This statistical omission lead to the admission: "The Commission recognises that the ABS resident population estimates have limitations when used for assessing housing demand. Given the significant influx of foreigners coming to work or study in Australia in recent years, it seems highly likely that short-stay visitor movements may have added to the demand for housing. However, the Commissions are unaware of any research that quantifies the effects." [44]

Two editors of Wikipedia have opposing views on a text entitled "Recent concerns about New Zealanders taking Australian jobs”. Consensus is requested. If you want to give us your opinion or have more information to add to it, please express your opinion on the talk page. |

Employment

There are thousands of low-cost IT workers entering Australia who are undermining the job prospects of new computer science graduates and reducing salaries in the IT industry.[45] However, other research sponsored by DIAC has found that Australia’s structured labour market along with the larger number of immigrants with higher education levels has tended to raise employment levels for Australians who are relatively unskilled.[46]

Australian trade unions have sometimes exposed attempts by employers to introduce foreign workers into the country in order to avoid paying local workers higher wages.[47]

In May 2008, former Immigration Minister Chris Evans said that he wanted "a major overhaul of the migrant program to boost numbers, promote unskilled as well as skilled applicants" and that "cabinet is expected to approve a pilot program for a guest worker scheme from the South Pacific." Senator Evans called this a "stalking horse" for the larger debate on unskilled migration.[48]

In October 2008, in response to a question concerning possible cuts to immigration levels resulting from possible rising unemployment due to the Global financial crisis of 2008–2009, former Prime Minister Rudd replied that : "As with all previous Governments . . whenever we set immigration targets, we will adjust them according to economic circumstances of the day. . . . What we’ll do in the future is adjust according to economic circumstances."[49]

In February 2009, Australia indicated that it will cut its annual immigration intake for the first time in eight years due to the slowing economy and weakening demand for labour. Former Immigration Minister Chris Evans said "It is fair to say that we expect the demand in the economy for labour to reduce. As it is a program very much linked to the demand for labour, we expect to run a smaller program."[50]

In March 2009, it was announced that "the Government has reduced this year's immigration target by 14 per cent because of the financial slowdown." The Permanent Migration program (skilled migrants) was cut to 115,000 people that financial year.[51]

The 2010–11 Migration Program was rebalanced towards the Skill Stream, which represented 67.5 per cent of the permanent Migration Program planning level. The program delivered 113 725 visas, which represents 67.4 per cent of the result.[10]

In a 2013 report, entitled "Scarce jobs: Migrants or locals at the end of the job queue?", Monash University academics Robert Birrell and Ernest Healy argued that immigration was hurting the job prospects of young Australians, with policymakers tending to "underestimate the scale of the recent migrant challenge for local youth who are seeking employment." According to Birrell and Healy:

"In the year to May 2013, there was an increase of 168,000 recently arrived overseas born migrants aged 15 plus in Australia. Of these, 108,200 were employed. This is almost as large as the 126,000 increase in employment in that year. The migration surge would not be an issue if the local working age population was stable or shrinking as some commentators assert. But it is not. Their numbers are growing strongly. It is young local workers who are the main losers in the competition for employment. This is especially the case for those without post-school education, who are seeking less skilled, entry-level jobs."[52]

The Sydney Morning Herald reported on November 2013 that:

"Education Minister Adrian Piccoli has called for a cap on the number of students allowed to enrol in teaching degrees to curb the state's oversupply of primary school teachers.

·

Fairfax Media revealed on Sunday more than 40,000 teachers are on a waiting list for permanent jobs in NSW and the oversupply of primary teachers is likely to last until the end of the decade even if resignations or retirements double."[53]

2011-2015 Graduate Stats

According to the Graduate Careers Survey,[11] full-time employment for newly qualified professionals from various occupations has declined since from 2011-2014. However, with some professions removed from the skilled shortage list (e.g. Dentistry) there has been a significant improvement from 2014-15. Some examples are:

| Field of Education | 2011[54] | 2013[55] | 2014[56] | 2015[57] | Change since 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentistry | 93.9% | 83.3% | 79.6% | 86.7% | -7.2 |

| Computer Science | 77.8% | 70.3% | 67.2% | 67.0% | -10.8 |

| Architecture | 68.5% | 60.0% | 57.8% | 70.2% | +1.8 |

| Psychology | 63.7% | 56.1% | 52.1% | 55.2% | -8.5 |

| Business Studies | 76.2% | 71.8% | 69.7% | 70.8% | -5.4 |

| Mechanical Engineering | 87.1% | 82.4% | 71.0% | 72.2% | -14.9 |

| Surveying | 92.9% | 86.5% | 83.9% | 90.7% | -2.2 |

| Health Other | 77.0% | 69.7% | 70.4% | 69.2% | -7.8 |

| Nursing (Initial) | 92.0% | 83.1% | 80.5% | 79.0% | -13 |

| Nursing (Post-Initial) | 84.9% | 71.4% | 75.8% | 74.9% | -10 |

The professional associations of some of these occupations have expressed their criticism of the immigration policy.

For example, The Australian newspaper reported that:

"DENTISTS have fallen in behind vets, optometrists and dietitians in asking the government to cap university places to relieve an oversupply of graduates. But the Australian Dental Association has gone further, demanding an end to work rights for international graduates of Australian dentistry degrees."[58]

The Australian Dental Association has expressed its criticism in recent years[59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68] and said that:

"There is substantial oversupply in metropolitan areas as indicated by the number of applications received for each advertised position in both the public and private sector, the proportion of full-time to part-time work available and the number of dentists who report difficulty in obtaining full-time work."

...

"Overseas qualified dentists who have met registration requirements in New Zealand receive automatic recognition in Australia .... Achieving registration in New Zealand is seen by many as a means of 'back door' entry into Australia"[13]

Optometry Australia has expressed that:

" 'Optometric supply and demand in Australia: 2011-2036' forecasts a significant oversupply of optometrists under nine different scenarios of service demand."[69][70]

The Australian newspaper reported about the veterinary occupation that:

"Competition for jobs is so high that starting salaries are about $45,000 and average annual salary for all vets in the vicinity $75,000 - for a course that takes five to seven years.

Oversupply is very real, says Dr Neutze. Australia has 455 vets per million population, compared with Britain on 349, the US (281) and Canada (429)....

Unlike the Australian Medical Association, which has been lobbying hard against more new medical schools - including at Charles Sturt and Curtin universities, which both have proposals sitting with governments - the AVA has struggled to get its message across to the general public."[71]

ABC News reported that: "Thousands of nursing graduates are unable to find work in Australian hospitals, according to the nurses' union."[72]

Architecture and Design reported that:

"The Design Institute of Australia (DIA), Australia’s peak multi-disciplinary body for professional designers, has released an important discussion paper based on the results of surveying nearly 1000 Australian designers.

...

"It is absolutely clear that the total number of designers in Australia far outstrips the realistic commercial demand for design services," notes David Robertson LFDIA, author of the discussion paper, and a design business owner himself."[73]

The Australian newspaper reported that:

"University of Technology, Sydney accounting lecturer Amanda White said any decision to drop accounting would hit international student numbers, who were a large component of accounting courses.

·

She said while some international students chose to study in Australia so they could take their skills back home, many did so with the hope of eventually migrating to Australia and finding jobs in the country.

...

Dr White said while the peak accounting bodies had argued there was a shortage of skilled accountants in Australia, anecdotally, students had been reporting that it was tougher to find jobs."[74]

The risk is that high unemployment can encourage xenophobia and protectionism as workers fear that foreigners are stealing their jobs.[75][76]

There is also the risk that the government receives less revenue if the work rights for international graduates are ended, since it is known that for many students the ability to stay in Australia after graduation is the only reason they come to study in Australia as Martin Davies, academic at the University of Melbourne, explained:

"For many students, permanent residency—not necessarily the calibre of our qualifications—has become a raison d’être for studying in Australia."[77]

"This massive growth has certainly had its good side. It has turned the Australian higher education sector from a relatively small contributor to the Australian economy, to a major influence. The international education sector now injects more than $15.5 billion into the Australian economy annually. Tertiary education now represents the largest service sector in the country, and the third-largest sector overall (after coal and iron ore)."[77]

Economy

The former Federal Treasurer, Peter Costello considers that Australia is underpopulated due to low birth rate, and claims that negative population growth will have adverse long-term effects on the economy as the population ages and the labour market becomes less competitive.[78] To avoid this outcome the government has increased immigration to fill gaps in labour markets and introduced a subsidy to encourage families to have more children. However, opponents of population growth such as Sustainable Population Australia do not accept that population growth will decline and reverse, based on current immigration and fertility projections.[79]

There is debate over whether immigration can slow the ageing of Australia's population. In a research paper entitled Population Futures for Australia: the Policy Alternatives, Peter McDonald claims that "it is demographic nonsense to believe that immigration can help to keep our population young."[80] However, according to Creedy and Alvarado (p. 99),[81] by 2031 there will be a 1.1 per cent fall in the proportion of the population aged over 65 if net migration rate is 80,000 per year. If net migration rate is 170,000 per year, the proportion of the population aged over 65 would reduce by 3.1 per cent. As of 2007 during the leadership of John Howard, the net migration rate was 160,000 per year.[82]

According to the Commonwealth Treasury, immigration can reduce the average age of the Australian population: "The level of net overseas migration is important: net inflows of migrants to Australia reduce the rate of population ageing because migrants are younger on average than the resident population. Currently, around 85 per cent of migrants are aged under 40 when they migrate to Australia, compared to around 55 per cent for the resident population."[83]

Ross Gittins, an economics columnist at Fairfax Media, backs up the Treasury study, claiming that the Liberal Party's focus on skilled migration has reduced the average age of migrants. "More than half are aged 15 to 34, compared with 28 per cent of our population. Only 2 per cent of permanent immigrants are 65 or older, compared with 13 per cent of our population."[84] Because of these statistics, Gittens claims that immigration is slowing the ageing of the Australian population. He also claims that the emphasis on skilled migration also means that the "net benefit to the economy is a lot more clear-cut."

Robert Birrell, director of the Centre for Population and Urban Research at Monash University, has argued: "It is true that a net migration intake averaging around 180,000 per year will mean that the proportion of persons aged 65 plus to the total population will be a few percentage points lower in 2050 than it would be with a low migration intake. But this ‘gain’ would be bought at the expense of having to accommodate a much larger population. These people too, will age, thus requiring an even larger migration intake in subsequent years to look after them."[85]

In July 2005 the Productivity Commission launched a commissioned study entitled Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth,[86] and released an initial position paper on 17 January 2006[87] which states that the increase of income per capita provided by higher migration (50 percent more than the base model) by the 2024–2025 financial year would be $335 (0.6%), an amount described as "very small." The paper also found that Australians would on average work 1.3 percent longer hours, about twice the proportional increase in income.[88]

Using regression analysis, Addison and Worswick found that "there is no evidence that immigration has negatively impacted on the wages of young or low-skilled natives." Furthermore, Addison's study found that immigration did not increase unemployment among native workers. Rather, immigration decreased unemployment.[89] These findings, however, are at odds with those of the Productivity Commission which found in 2005 that higher immigration levels would result in lower wage growth for existing Australian residents.[90] On the impact of immigration on unemployment levels, the Productivity Commission noted: "The conclusion that immigration has not caused unemployment at an aggregate level does not imply that it cannot lead to higher unemployment for specific groups. Immigration could worsen the labour market outcomes of people who work in sectors of the economy that have high concentrations of immigrant workers."

Gittins claims there is considerable opposition to immigration in Australia by "battlers" because of the belief that immigrants will steal jobs. Gittins claims though that "it's true that immigrants add to the supply of labour. But it's equally true that, by consuming and bringing families who consume, they also add to the demand for labour – usually by more."[84] Overall, Gittins has written that the "economic case for rapid population growth though immigration is surprisingly weak," noting the diseconomies of scale, infrastructure costs and negative environmental impacts associated with continued immigration-driven population growth.[91]

Robert Birrell has asserted that high immigration levels are being used by the Federal Government to stimulate aggregate economic growth. Yet, according to Birrell:

These aggregate growth priorities do not accord with the interests of Australian residents. What matters most to them is per capita economic growth. As the Productivity Commission has established, existing residents have little if anything to gain from high migration. In an economy increasingly dependent on the export of non-renewable resources, rapid population expansion dilutes the benefit from the eroding bounty that can accrue to existing residents. A slowdown in the rate of workforce growth is also a net benefit for existing residents. It means that governments and employers will have to pay more attention to the training, wages and conditions they offer workers to attract and keep them in the workforce. Nor will a slowdown in labour force growth be a serious problem if labour can be focused on internationally competitive industries rather than city building.[85]

Infrastructure

Individuals and interest groups such as Sustainable Population Australia filed submissions in response to the Productivity Commission's position paper, arguing among other things that immigration causes a decline in wealth per capita and leads to environmental degradation and overburdened infrastructure, the latter creating a costly demand for new infrastructure.[92][93] However, the Productivity Commission's final research report found that it was not possible to reliably assess the impact of environmental limitations upon productivity and economic growth, nor to reliably attribute the contribution of immigration to any such impact.[94]

Australia is a relatively high-immigration country like Canada (the country with the highest per capita immigration rate in the world, see Immigration to Canada) and the United States, and while other economically developed countries like Japan and Korea have historically had negligible immigration,[95] the issue of population decline is forcing a rethink of such policies.

Nobel laureate economist Gary Becker from the University of Chicago, in a piece published in the Wall Street Journal, wrote, "The only solution for countries that continue to be concerned about a future with declining and aging populations is to open their gates to immigration. Yet in most countries large-scale immigration creates political, economic and social problems. Immigration is an especially unwelcome alternative for Japan, given the history of Japanese reluctance to have many foreigners settling in their country. As a result, Japan but not Russia and many other countries face a worrisome demographic and economic future."[95]

Social

Robert Birrell has argued that immigration is creating social divisions and risks long-term national unity. According to Birrell: "The fact that Australia already has one of the highest rates of foreign-born persons in any developed society and that most of our migrants come from non-English-speaking-background (NESB) countries with little cultural affinity to that of Australia does not seem to have been considered." He points to urban settlement patterns and their implications for social differentiation. Birrell states: "Social divisions are becoming more obvious and geographically concentrated. NESB areas are being overlain by an ethnic identification. These trends will intensify if the population grows because competition for amenities will intensify."[85]

According to urban anthropologist and ethologist Frank Salter, immigration is creating "ethnic stratification" in Australian society. Salter asserts: "Aboriginal Australians remain an economic underclass and some immigrant communities show high levels of unemployment. Anglo Australians, still almost 70 percent of the population, are presently being displaced disproportionately in the professions and in senior managerial positions by Asian immigrants and their children. The situation is dramatic at selective schools which are the high road to university and the professions."[96] According to Salter: "Any [immigration] policy is suspect that threatens a country’s ecological sustainability, increases diversity or tends to subordinate the core ethnic group."

Immigration and ageism

Claims have been made that Australia's migration program is in conflict with anti age-discrimination legislation and there have been calls to remove or amend the age limit of 50 for general skilled migrants.[97]

Immigration and Australian politics

Multiculturalism policy

Australia gradually became a promising land with the vastness of land in contrast to rareness of labour. Around 1970, there was a fundamental change in immigration policy. Millions of migrants and refugees came to Australia during the 1970s which resulted in the issue of a policy of multiculturalism.[14] For the first time since 1788 there were more migrants wanting to come (even without a subsidy) than the government wanted to accept. All subsidies were abolished, and immigration became progressively more difficult.

During the 2001 election campaign, asylum-seekers and border protection became a hot issue, as a result of incidents such as the 11 September 2001 attacks, the Tampa affair, Children overboard affair, and the sinking of the SIEV-X. This incident marked the beginning of the controversial Pacific Solution. The Howard government's success in the election was largely due to the strong public support for its restrictive policy on asylum-seekers. However, the overall level of immigration increased substantially over the life of the Howard Government.

Nowadays, Australia, which is a popular destination of migrants all over the world, has become one of the most multicultural and diverse countries with more than 200 languages and about 25 percent of the population from overseas countries of birth.[14]

Political trends

Over the last decade, leaders of the major Federal political parties have demonstrated support for high level immigration (including John Howard, Peter Costello and Kim Beazley[98][98]). There was, overall, an upward trend in the number of immigrants to Australia over the period of the Howard Government (1996–2007). The Rudd Labor Government (elected 2007) increased the quota again once in office.[99] In 2010, both major parties continue to support high immigration, with former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd advocating a 'Big Australia'; and Opposition Leader Tony Abbott stating in a 2010 Australia Day speech that: "My instinct is to extend to as many people as possible the freedom and benefits of life in Australia".[100]

Controversy

Immigration policy has often been controversial – notably during the economic down-turn of the early 1990s when the policy of mandatory detention of unauthorised arrivals was established by the Australian Labor Party government of Paul Keating in 1992.[101] Designed to prevent circumvention of Australia's refugee immigration processes, the practice did not alter Australia's overall commitment to accepting refugees, but it became increasingly high profile and controversial during the period of the Coalition Government of John Howard, particularly after a system of processing claims for asylum offshore at Christmas Island, Nauru and Papua New Guinea was established (The Pacific Solution). While the policy was initially popular in the electorate, it came under criticism from a range of religious, community and political groups including the National Council of Churches, Amnesty International, Australian Democrats, Australian Greens and Rural Australians for Refugees, as well as high profile members of the Parliamentary Liberal Party led by Petro Georgiou.[102] In 2005 the Liberal Government finally ended the practice of detention of children which had been established under the previous Labor Government and consistently promulgated by the Liberals.

Anti-immigration policies were a major plank of the One Nation Party, formed by Pauline Hanson in the late 1990s (the movement also championed economic protectionism and increased government support for regional Australia). Although Hanson lost her seat at the subsequent election, the Party obtained brief electoral success winning one Senate position at the 1998 Federal Election, and 11 of 89 seats in the 1998 State Election in Queensland (although state parliaments have no jurisdiction over immigration and the Party did not maintain unity once sitting in the Parliament).[103] One Nation argued for a zero net immigration policy, asserting that "environmentally Australia is near her carrying capacity, economically immigration is unsustainable and socially, if continued as is, will lead to an ethnically divided Australia."[104] The Party is now electorally marginalised.

In 2001 the Tampa affair and Children Overboard Affair caused significant political controversy. In August, the Tampa, a Norwegian vessel, went to the rescue of a sinking boat carrying over 400 asylum seekers bound for Australia. The Howard government refused to allow the asylum seekers to land at Christmas Island, causing a diplomatic dispute with Norway, and leading to the establishment of the Pacific Solution whereby claims for asylum by unauthorised arrivals would be processed at offshore locations.[105] In October, during an election campaign, the Government relayed to the media incorrect advice from the Royal Australian Navy that asylum seekers had "thrown their children overboard" in an effort to secure asylum.[106] Subsequently the incident became known as the Children Overboard Affair, and politicians and commentators (notably David Marr of the Sydney Morning Herald) have accused the Howard government of deception and of exploiting the incident for political purposes.[107] Former Prime Minister Howard denies this.[108]

In 2003, economist Ross Gittins, a columnist at Fairfax Media, said former Prime Minister John Howard had been "a tricky chap " on immigration, by appearing "tough" on illegal immigration to win support from the working class, while simultaneously winning support from employers with high legal immigration.[109]

In 2006, the Labor Party under Kim Beazley took a stance against the importation of increasingly large numbers of temporary skilled migrant workers ("foreign workers") by employers, arguing that this is simply a way for employers to drive down wages.[98] At the same time, it is estimated that a million Australians are employed outside Australia.[98]

Kevin Rudd's Labor government announced in July 2008, that the "majority" of asylum seekers would no longer be detained and that "a person who poses no danger to the community will be able to remain in the community while their visa status is resolved." Mandatory detention will now apply to three groups who "pose a risk to the wider community": those who have repeatedly breached their visa conditions or those who have security, identity or health risks. However, asylum seekers who arrive at Christmas Island will still also be detained for health and security checks and will also continue to be processed at Christmas Island.[110] Boat arrivals dramatically increased during 2009, as did reports of drownings on people smuggling boats and controversy continues to surround the issue of the best way to process unauthorised immigration arrivals and to dissuade people-smugglers from profiteering from dangerous voyages to Australia.[111][112] As of 29 March 2010, 100 asylum seeker boats had arrived in Australian waters during the life of the Rudd government.[113]

Current issues

Detention of asylum seekers is consistently topical.[114] Mr Patrick McGorry, Australian of the Year 2009 and mental health advocate, called for an end to the policy of mandatory detention on Australia Day 2010. In response, the then Deputy Prime Minister Julia Gillard re-affirmed the Rudd Government's commitment to the policy: "We believe mandatory detention is necessary when people arrive unauthorised, for security reasons, in order to do health checks and in order to check identity, and we will continue to have a mandatory detention policy".[115]

The Rudd government announced a temporary suspension on processing of refugee claims for asylum seekers from Afghanistan and Sri Lanka who arrived in Australia after 9 April 2010.[116] This policy has received serious criticism from local and international human rights groups,[117] despite the Rudd government's assertions that the safety of minority groups is improving in both countries.

In April 2010, the Rudd government announced its decision to re-open the remote Curtin Detention Centre in Western Australia, which once housed more than 1000 asylum seekers, but was decommissioned in 2002 after riots, reports of violence and detainee mistreatment. This decision was heavily criticised by refugee advocate groups who called the move "punitive" and an abuse of human rights, and liken the facilities at the former RAAF base to a "hell hole".[118]

The debate about Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs) continues, and Leader of the Opposition Tony Abbott recently floated the idea of bringing TPVs back in an attempt to discourage asylum seekers.[119] The TPV regime is consistently criticised for its approach of leaving legitimate, recognised refugees in limbo, and also because of the limitations on TPV holders sponsoring family members to Australia.

With projections of a population of 35 million by 2050, debate is underway in Australia as to how to organise infrastructure accordingly.[120] The former Federal Finance Minister Lindsay Tanner has rejected arguments that Australia should consider lowering immigration on environmental grounds, saying in 2009 that the "primary source of stress on our urban and natural environments is bad management not population growth". Former Premier of New South Wales Bob Carr remains a vocal critic of high immigration, believing that population growth is unsustainable on a dry continent, commenting in 2009: "because of a very significant ramping up of the immigration intake, really a doubling of the intake, over the last five years, that we're looking at a population of... 42.5 million by 2055. And I am very worried about that. I don't think we've got the carrying capacity.".[121] The Australian Greens also claim to favour keeping Australia's population low on environmental grounds, but they do not have any policy on the appropriate level of immigration.[122] Sustainable Australia on the other hand has a comprehensive policy on this issue [123]

On 19 July 2013 in a joint press conference with PNG Prime Minister Peter O'Neill and Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd detailed the Regional Resettlement Arrangement (RRA) between Australia and Papua New Guinea:[124]

"From now on, any asylum seeker who arrives in Australia by boat will have no chance of being settled in Australia as refugees. Asylum seekers taken to Christmas Island will be sent to Manus and elsewhere in Papua New Guinea for assessment of their refugee status. If they are found to be genuine refugees they will be resettled in Papua New Guinea... If they are found not to be genuine refugees they may be repatriated to their country of origin or be sent to a safe third country other than Australia. These arrangements are contained within the Regional Resettlement Arrangement signed by myself and the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea just now."

People who travel to Australia for financial reasons may not meet the international definition of refugee.[125] There is currently keen debate around the world and in Australia regarding how to distinguish a refugee versus an economic migrant.[126] These terms are used to distinguish between people with genuine refugee claims and people who choose to move to Australia on economic grounds. An example of this is Hussein Khodor from Qabeet who "sold his small poster shop in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli to pay the $80,000 cost of smuggling him and his family to Australia where he hoped to build a better life".[127] Many people who have travelled to Australia by boat using people smuggler networks have died.[127]

In October 2013 Immigration Minister Scott Morrison instructed departmental and detention centre staff to publicly refer to asylum seekers as ‘‘illegal’’ arrivals and as ‘‘detainees’’, rather than as clients.[128]

The cost per person who arrives illegally by boat claiming to be an asylum seeker in Australia is estimated to be more than $70,000.[129] Liberal Democrats senator-elect David Leyonhjelm proposed in 2013 to charge asylum seekers $50,000 for permanent residency in Australia saying "If you don't think you can get a job and support yourself, you don't come,".[130] The federal budget for handling asylum seeker issues for 2013-2014 is AUD$2.9 billion.

People who arrived in Australian waters who sought asylum since August 13, 2012 received no benefit compared with people who stayed in refugee camps who waited to be processed.[131]

See also

- Visa policy of Australia

- Demographics of Sydney

- Demographics of Australia

- Department of Immigration and Border Protection

- Post war immigration to Australia

- German Australian

- French Australian

- Migration Alliance

References

- ^ a b https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/human-journey/

- ^ https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/migration-to-australia/

- ^ Smith, Debra (9 May 2007). "Out of Africa – Aboriginal origins uncovered". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

Aboriginal Australians are descended from the same small group of people who left Africa about 70,000 years ago and colonised the rest of the world, a large genetic study shows. After arriving in Australia and New Guinea about 50,000 years ago, the settlers evolved in relative isolation, developing unique genetic characteristics and technology.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/immigration

- ^ [1]

- ^ The Conversation, The changing face of Australian immigration

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics, International migration

- ^ Australian Bureau of noms

- ^ Markus, Andrew. "Attitudes to immigration and cultural diversity in Australia." Journal of Sociology 50.1 (2014): 10-22.

- ^ a b [2]

- ^ a b http://www.graduatecareers.com.au/research/surveys/australiangraduatesurvey/

- ^ Immigration to Australia#2014

- ^ a b http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1411/M829809_v1_635525128596298953.pdf

- ^ a b c "Migration Expert – History of Australian Immigration". Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ a b Price, Charles (1987). "Chapter 1: Immigration and Ethnic Origin". In Wray Vamplew (ed.) (ed.). Australians: Historical Statistics. Broadway, New South Wales, Australia: Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates. pp. 2–22. ISBN 0-949288-29-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ "Ten Pound Poms". ABC Television (Australia). 1 November 2007.

- ^ "Ten Pound Poms". Museum Victoria. 10 May 2009.

- ^ The Emigration Group (23 April 2013). "Australia Skilled Working visas". Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Australian Visa Bureau (22 December 2011). "Australia visas". Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Fact Sheet 60 – Australia's Refugee and Humanitarian Programme

- ^ Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Border Protection Fact Sheet 60

- ^ Australian Immigration Fact Sheet 60 - Australia's Refugee and Humanitarian Program Template:Webcite

- ^ Australian Immigration Agency http://www.australianimmigrationagency.com/

- ^ "New body to regulate migration agents". Minister.immi.gov.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Australian Immigration Fact Sheet 66. Humanitarian Settlement Services

- ^ a b "3412.0 – Migration, Australia, 2005–06" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 29 March 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b "3412.0 – Migration, Australia, 2009–10" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Procter, Nicholas, et al. "Mental health of people of immigrant and refugee backgrounds." Mental Health (2014): 197. "If current rates of immigration to Australia continue to grow, it is estimated that by 2050 approximately one-third of Australia's population will be overseas-born"

- ^ Template:Fr icon Jacques Neirynck, "Pour son bien-être, la Suisse doit rester une terre d’immigration", Le Temps, Friday 20 September 2011.

- ^ 3412.0 - Migration, Australia, 2014-15 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "2006 Census Data : View by Location Or Topic". Censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Foran, B., and F. Poldy, (2002), Future Dilemmas: Options to 2050 for Australia's population, Technology, Resources and Environment, CSIRO Resource Futures, Canberra.

- ^ "Baby Bonus Bad for Environment" (PDF). population.org.au. Sustainable Population Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Optimum Population Trust". Optimumpopulation.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bill Miller (27 June 2007). "Rich nations blamed for global warming, but not for all the right reasons". Desmogblog.com. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Australia faces worse, more frequent droughts: study, Reuters

- ^ Metropolis strives to meet its thirst, BBC News

- ^ "Perth to become a desert 'Ghost City', according to FOX News". 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Population Growth and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Tai.org.au. 10 July 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "High Population Policy Will Double Greenhouse Gas Growth". Tai.org.au. 10 July 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Nature. "Access". Nature. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Klan, A. (17 March 2007) Locked out

- ^ Wade, M. (9 September 2006) PM told he's wrong on house prices

- ^ a b c d "Microsoft Word - prelims.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Australian Financial Review 7/7/04, "Immigrants taking local IT jobs: report"

- ^ DIMA research publications (Garnaut), Migration to Australia and Comparisons with the United States: Who Benefits?, p.21

- ^ LaborNET Foreign Labour Used to Lower Wages Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Labor promises massive increase in migration to lure workers". Theaustralian.news.com.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.[dead link]

- ^ PM Rudd – 3AW Interview Archived 2014-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Slowing economy forces immigration cut 23Feb 2009". Business.smh.com.au. 23 February 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Immigration cut only temporary 16Mar 2009". Abc.net.au. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Scarce jobs: migrants or locals at the end of the job queue". The Conversation. 28 August 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ http://www.smh.com.au/national/education/piccoli-calls-for-cap-on-teaching-degrees-20131120-2xvm8.html

- ^ http://www.graduatecareers.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/gca002770.pdf

- ^ http://www.graduatecareers.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/GCAGradStats2013.pdf

- ^ http://www.graduatecareers.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/GCA_GradStats_2014.pdf

- ^ "2015 Graduate Stats" (PDF). Retrieved 08/07/2016.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/dentists-join-the-growing-calls-for-cap-on-student-uni-places/story-e6frgcjx-1226871304881

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1412/M838155_v1_635545178851658624.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1405/M764403_v1_635345549375904529.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1306/M622830_v1_635068198974665016.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1407/M786159_v1_635400641731797089.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1406/M783727_v1_635393882999427518.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1403/M751647_v1_635316017667250313.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1303/M491843_v1_634981571906615480.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1301/M476721_v1_634944463847345477.pdf

- ^ http://www.ada.org.au/App_CmsLib/Media/Lib/1206/M415993_v1_634763968722800952.pdf

- ^ http://www.smh.com.au/national/dental-glut-sparks-call-to-cap-university-graduates-20130111-2clhp.html

- ^ http://www.optometrists.asn.au/our-news.aspx

- ^ http://www.optometrists.asn.au/blog-news/2014/6/23/workforce-report-forecasts-1,200-excess-by-2036.aspx

- ^ http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/surfeit-of-vets-prompts-call-to-cap-places/story-e6frgcjx-1226807060998

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-05-24/thousands-of-nursing-graduates-unable-to-find-work/5475320

- ^ http://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/news/does-australia-have-too-many-designers

- ^ http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/immigration/accounting-not-cut-from-immigration-skilled-occupations-list-for-2015/story-fn9hm1gu-1227120626345

- ^ Steininger, M.; Rotte, R. (2009). "Crime, unemployment, and xenophobia?: An ecological analysis of right-wing election results in Hamburg, 1986–2005". Jahrbuch für Regionalwissenschaft. 29 (1): 29–63. doi:10.1007/s10037-008-0032-0.

- ^ Unemployment#Social

- ^ a b http://quadrant.org.au/magazine/2010/03/the-permanent-residency-rort/

- ^ "Costello hatches census-time challenge: procreate and cherish". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 July 2006.

- ^ Goldie, J. (23 February 2006) "Time to stop all this growth" (Retrieved 30 October 2006)

- ^ McDonald, P., Kippen, R. (1999) Population Futures for Australia: the Policy Alternatives Archived 2011-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Population Ageing, Migration and Social Expenditure". Amazon.com. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Farewell, John. We will never forget you". The Age. Melbourne. 25 November 2007.

- ^ "Part 2: Long-term demographic and economic projections". Treasury.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Back-scratching at a national level". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 June 2007.

- ^ a b c Birrell, B. The Risks of High Migration, Policy, Vol. 26 No. 1, Autumn 2010

- ^ [3] Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Productivity Commission, Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth (Position Paper), p. 73 Archived 2006-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Productivity Commission, Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth Key Points Archived 2006-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Addison, T. and Worswick, C. (2002). The impact of immigration on the earnings of natives: Evidence from Australian micro data. [4], Vol. 78, pp. 68–78.

- ^ Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth

- ^ Gittins, R. Beware gurus selling high migration, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 December 2010

- ^ Claus, E (2005) Submission to the Productivity Commission on Population and Migration (submission 12 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth). Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nilsson (2005) Negative Economic Impacts of Immigration and Population Growth (submission 9 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth). Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Productivity Commission, Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth (Research Report), p.119 Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "The Wall Street Journal Online – Extra". Opinionjournal.com. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Salter, F. The Misguided Advocates of Open Borders, Quadrant, Volume LIV Number 6, June 2010.

- ^ How old is too old? Calls are being made to lift or abolish the age restriction for General Skilled Migrants amid claims Australia's migration program could be in conflict wit...

- ^ a b c d "Workers of the World", Background Briefing, Radio National Sunday 18 June 2006

- ^ "Lateline – 11/06/2008: Immigration intake to rise to 300,000". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Hudson, Phillip (23 January 2010). "Abbott urges more migration, compassion for boat people". The Advertiser.

- ^ "Timeline: Asylum seekers : World News Australia on SBS". Sbs.com.au. 14 October 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Gordon, Michael (22 November 2008). "Georgiou, the party conscience, to quit". The Age. Melbourne.

- ^ "1998 Queensland Election (Current Issues Brief 2 1998–99)". Aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "One Nation's Immigration, Population and Social Cohesion Policy 1998". Australianpolitics.com. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Australia ships out Afghan refugees". BBC News. 3 September 2001.

- ^ "Parliament of Australia: Senate: Select Committee for an inquiry into a certain maritime incident – Report". Aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Truth overboard – the story that won't go away". The Sydney Morning Herald. 28 February 2006.

- ^ "Insiders – 17/02/2002: Howard denies deliberate deception in children overboard claims". Abc.net.au. 17 February 2002. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ Gittens, R. (20 August 2003). Honest John's migrant twostep. The Age. Retrieved 2 October from http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2003/08/19/1061261148920.html

- ^ "Sweeping changes to mandatory detention announced: ABC News 29/7/2008". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Rudd 'like Howard' on asylum seekers". AAP. 26 October 2009.

- ^ Johnston, Tim (30 July 2008). "Australia Announces Changes on Asylum Seekers". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Rudd Government marks 100th asylum seeker boat". The Australian. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ McKenzie, J. and Hasmath, R. (2013) “Deterring the ‘Boat People’: Explaining the Australian Government's People Swap Response to Asylum Seekers”, Australian Journal of Political Science 48(4): 417–430.

- ^ Overington, Caroline (26 January 2010). "Julia Gillard shoots down Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry's call to shut detention centres". The Australian. News Limited.

- ^ online political correspondent Emma Rodgers (9 April 2010). "Rule changes leave asylum seekers in limbo – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Asia Pacific:Story:45 human rights groups condemn Aust asylum claim suspension". Radio Australia. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ AM Simon Santow. "Asylum seekers sent to Curtin 'hell hole' – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Refugee group slams Abbott's boat threat – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 1 January 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "The shape of a big country". The Australian. 31 October 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Lateline – 11/12/2009: Bracks, Carr discuss population growth". Abc.net.au. 11 December 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Population". The Australian Greens. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "SUSTAINABLE POPULATION & IMMIGRATION - AUSTRALIA". Sustainable Australia. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ REGIONAL RESETTLEMENT ARRANGEMENT BETWEEN AUSTRALIA AND PAPUA NEW GUINEA. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/national/country-shoppers-targeted-by-abbott/story-fncynkc6-1226523155100

- ^ Lubbers, Ruud (5 April 2004). "Refugees and migrants: Defining the difference". BBC News.

- ^ a b "AFP was told doomed asylum seekers were on their way". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/minister-wants-boat-people-called-illegals-20131019-2vtl0.html

- ^ "Australia will be paying $70,000 for each asylum seeker that arrives". News Corp Australia Network. 3 June 2013.

- ^ "Charge asylum seekers $50,000 to come here, says incoming senator". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ The Conversation, FactCheck: are asylum seekers really economic migrants?

- Commonwealth of Australia. Migration Act 1958

Further reading

- Betts, Katharine. Ideology and Immigration: Australia 1976 to 1987 (1997)

- Burnley, I.H. The Impact of Immigration in Australia: A Demographic Approach (2001)

- Foster, William, et al. Immigration and Australia: Myths and Realities (1998)

- Jupp, James. From White Australia to Woomera: The Story of Australian Immigration (2007) excerpt and text search

- Jupp, James. The English in Australia (2004) excerpt and text search

- Jupp, James. The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, its People and their Origins (2002)

- Markus, Andrew, James Jupp and Peter McDonald, eds. Australia's Immigration Revolution (2010) excerpt and text search

- O'Farrell, Patrick. The Irish in Australia: 1798 to the Present Day (3rd ed. Cork University Press, 2001)

- Wells, Andrew, and Theresa Martinez, eds. Australia's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook (ABC-CLIO, 2004)

External links

- Department of Immigration and Border Protection of Australia

- Costello hope for skilled migrant intake

- NSW training Chinese workers

- Chinese Museum - Museum of Chinese immigration to Australia in Melbourne

- Origins: Immigrant Communities in Victoria – Immigration Museum, Victoria, Australia

- NSW Migration Heritage Centre, Australia

- Office of The Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA)

- Australian State of Queensland skilled and business migration information site

- Australian State of Victoria official site for skilled and business migrants

- Culture Victoria – Stories about migration to Australia

- Migration Alliance - Peak Society for Australian Migrants and Migration Agents (Not-for-profit incorporated association)

- Jupp, James (2008). "Immigration". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 4 October 2015. (Immigration in Sydney) [CC-By-SA]