Somali Armed Forces

| Somali Armed Forces | |

|---|---|

| Ciidamada Qalabka Sida القوات المسلحة الصومالية | |

| Founded | 1960 |

| Service branches | Somali National Army[1] Somali Air Force[1] Somali Navy[1] |

| Headquarters | Mogadishu, Somalia |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | Hassan Sheikh Mohamud |

| Minister of Defence | Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini |

| Chief of Army | Mohamed Adam Ahmed |

| Personnel | |

| Military age | 18 |

| Available for military service | 2,260,175 (2010 est.; males) 2,159,293 (2010 est.; females), age 18–49 |

| Fit for military service | 1,331,894 (2010 est.; males) 1,357,051 (2010 est.; females), age 18–49 |

| Reaching military age annually | 101,634 (2010 est.; males) 101,072 (2010 est.; females) |

| Active personnel | 20,000[2] |

| Expenditure | |

| Percent of GDP | 0.9% (2005) |

| Industry | |

| Foreign suppliers | |

The Somali Armed Forces (SAF) are the military forces of Somalia, officially known as the Federal Republic of Somalia.[3] Headed by the President as Commander in Chief, they are constitutionally mandated to ensure the nation's sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity.[4]

The SAF was initially made up of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Police Force.[5] In the post-independence period, it grew to become among the larger militaries in Africa.[6] Due to patrimonial and repressive state policies, the military had by 1988 begun to disintegrate.[7] By the time dictator Siad Barre fled in 1991, the armed forces had dissolved.[8] As of January 2014, the security sector is overseen by the Government of Somalia's Ministry of Defence, Ministry of National Security.[9] The Somaliland, and Puntland regional governments maintain their own security and police forces.

History

Middle Ages to colonial period

Historically, Somali society conferred distinction upon warriors (waranle) and rewarded military acumen. All Somali males were regarded as potential soldiers, except for the odd religious cleric (wadaado).[10] Somalia's many Sultanates each maintained regular troops. In the early Middle Ages, the conquest of Shewa by the Ifat Sultanate ignited a rivalry for supremacy with the Solomonic dynasty.

Many similar battles were fought between the succeeding Sultanate of Adal and the Solomonids, with both sides achieving victory and suffering defeat. During the protracted Ethiopian-Adal War (1529–1559), Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi defeated several Ethiopian Emperors and embarked on a conquest referred to as the Futuh Al-Habash ("Conquest of Abyssinia"), which brought three-quarters of Christian Abyssinia under the power of the Muslim Adal Sultanate.[11][12] Al-Ghazi's forces and their Ottoman allies came close to extinguishing the ancient Ethiopian kingdom, but the Abyssinians managed to secure the assistance of Cristóvão da Gama's Portuguese troops and maintain their domain's autonomy. However, both polities in the process exhausted their resources and manpower, which resulted in the contraction of both powers and changed regional dynamics for centuries to come. Many historians trace the origins of hostility between Somalia and Ethiopia to this war.[13] Some scholars also argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock musket, cannons and the arquebus over traditional weapons.[14]

At the turn of the 20th century, the Majeerteen Sultanate, Sultanate of Hobyo, Warsangali Sultanate and Dervish State employed cavalry in their battles against the imperialist European powers during the Campaign of the Sultanates.

In Italian Somaliland, eight "Arab-Somali" infantry battalions, the Ascari, and several irregular units of Italian officered dubats were established. These units served as frontier guards and police. There were also Somali artillery and zaptié (carabinieri) units forming part of the Italian Royal Corps of Colonial Troops from 1889 to 1941. Between 1911 and 1912, over 1,000 Somalis from Mogadishu served as combat units along with Eritrean and Italian soldiers in the Italo-Turkish War.[15] Most of the troops stationed never returned home until they were transferred back to Italian Somaliland in preparation for the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.[16]

In 1914, the Somaliland Camel Corps was formed in the British Somaliland protectorate and saw service before, during, and after the Italian invasion of the territory during World War II.[10]

Modern

Just prior to independence in 1960, the Trust Territory of Somalia established a national army to defend the nascent Somali Republic's borders. A law to that effect was passed on 6 April 1960. Thus the Somali Police Force's Mobile Group (Darawishta Poliska or Darawishta) was formed. 12 April 1960 has since been marked as Armed Forces Day.[17] British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland, and the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somaliland) followed suit five days later.[18] On 1 July 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic.[19]

After independence, the Darawishta merged with the former British Somaliland Scouts to form the 5,000 strong Somali National Army.[20] The new military's first commander was Colonel Daud Abdulle Hirsi, a former officer in the British military administration's police force, the Somalia Gendarmerie.[10] Officers were trained in the United Kingdom, Egypt and Italy. Despite the social and economic benefits associated with military service, the armed forces began to suffer chronic manpower shortages only a few years after independence.[21]

Somali-Ethiopian Border War (1964)

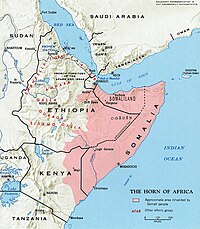

The Somali National Army (SNA) was battle-tested in 1964 when the conflict with Ethiopia over the Somali-inhabited Ogaden erupted into warfare. On 16 June 1963, Somali guerrillas started an insurgency at Hodayo, in eastern Ethiopia, a watering place north of Werder, after Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie rejected their demand for self-government in the Ogaden. The Somali government initially refused to support the guerrilla forces, which eventually numbered about 3,000. However, in January 1964, after Ethiopia sent reinforcements to the Ogaden, Somali forces launched ground and air attacks across the border and started providing assistance to the guerrillas. The Ethiopian Air Force responded with punitive strikes across its southwestern frontier against Feerfeer, northeast of Beledweyne and Galkacyo. On 6 March 1964, Somalia and Ethiopia agreed to a cease-fire. At the end of the month, the two sides signed an accord in Khartoum, Sudan, agreeing to withdraw their troops from the border, cease hostile propaganda, and start peace negotiations.

Shifta War

The Shifta War (1963–1967) was a secessionist conflict in which ethnic Somalis in the Northern Frontier District (NFD) of Kenya (a region that is and has historically been almost exclusively inhabited by ethnic Somalis[22][23][24]) attempted to join with their fellow Somalis in a Greater Somalia. The Kenyan government named the conflict "shifta", after the Somali word for "bandit", as part of a propaganda effort.

The province thus entered a period of running skirmishes between the Kenyan Army and the Northern Frontier District Liberation Movement (NFDLM) insurgents backed by the Somali Republic. One immediate consequence was the signing in 1964 of a Mutual Defense Treaty between Jomo Kenyatta's administration and the government of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie.[25]

In 1967, Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda mediated peace talks between Somali Prime Minister Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal and Kenyatta. These bore fruit in October 1967, when the governments of Kenya and Somalia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (the Arusha Memorandum) that resulted in an official ceasefire, though regional security did not prevail until 1969.[26][27] After a 1969 coup in Somalia, the new military leader Mohamed Siad Barre, abolished this MoU as he claimed it was corrupt and unsatisfactory. The Manyatta strategy is seen as playing a key role in ending the insurgency, though the Somali government may have also decided that the potential benefits of a war simply was not worth the cost and risk. However, Somalia did not renounce its claim to Greater Somalia.[25]

1969 Coup d'état

In 1968, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke narrowly escaped an assassination attempt. A grenade exploded near the car that was transporting him back from the airport, but failed to kill him.[28]

On October 15, 1969, while paying an official visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards.[28][29] On duty outside the guest-house where the president was staying, the officer fired an automatic rifle at close range, instantly killing Shermarke. Observers suggested that the assassination was inspired by personal rather than political motives.[28]

Shermarke's assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on October 21, 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Muhammad Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[29] Barre was installed as president of the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC), the new government of Somalia. Alongside him, the SRC was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Kediye officially held the title of "Father of the Revolution," and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[30] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[31][32] arrested members of the former government, banned political parties,[33] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[34]

In 2005, Cambridge historian Christopher Andrew published The World Was Going Our Way, a comprehensive account of KGB operations in Africa, Asia and Latin America co-authored with the late KGB Major Vasili Mitrokhin. Based on documents drawn from the Mitrokhin Archive, it alleges that Kediye had been a paid KGB agent codenamed "OPERATOR". Ironically, the KGB-trained National Security Service (NSS), the SRC's intelligence wing, had carried out Kediye's initial arrest.[1]

Ogaden War

Somalia committed to invade the Ogaden at 0300 13 July 1977 (5 Hamle, 1969), according to Ethiopian documents (some other sources state 23 July).[36] According to Ethiopian sources, the invaders numbered 70,000 troops, 40 fighter planes, 250 tanks, 350 armoured personnel carriers, and 600 artillery.[36] By the end of the month 60% of the Ogaden had been taken by the SNA-WSLF force, including Gode, which was captured by units commanded by Colonel Abdullahi Ahmed Irro. The attacking forces did suffer some early setbacks; Ethiopian defenders at Dire Dawa and Jijiga inflicted heavy casualties on assaulting forces. The Ethiopian Air Force (EAF) also began to establish air superiority using its Northrop F-5s, despite being initially outnumbered by Somali MiG-21s. However, Somalia was easily overpowering Ethiopian military hardware and technology capability. Army General Vasily Petrov of the Soviet Armed Forces had to report back to Moscow the "sorry state" of the Ethiopian army. The 3rd and 4th Ethiopian Infantry Divisions that suffered the brunt of the Somali invasion had practically ceased to exist.[37]

The USSR, finding itself supplying both sides of a war, attempted to mediate a ceasefire. When their efforts failed, the Soviets abandoned Somalia. All aid to Siad Barre's regime was halted, while arms shipments to Ethiopia were increased. Soviet military aid (second in magnitude only to the October 1973 gigantic resupplying of Syrian forces during the Yom Kippur War) and advisors flooded into the country along with around 15,000 Cuban combat troops. Other communist countries offered assistance: the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen offered military assistance and North Korea helped train a "People's Militia"; East Germany likewise offered training, engineering and support troops.[38] As the scale of communist assistance became clear in November 1977, Somalia broke diplomatic relations with the USSR and expelled all Soviet citizens from the country.

Not all communist states sided with Ethiopia. Because of the Sino-Soviet rivalry, China supported Somalia diplomatically and with token military aid. Romania under Nicolae Ceauşescu had a habit of breaking with Soviet policies and maintained good diplomatic relations with Siad Barre.

By 17 August, elements of the Somali army had reached the outskirts of the strategic city of Dire Dawa. Not only was the country's second largest military airbase located here, as well as Ethiopia's crossroads into the Ogaden, but Ethiopia's rail lifeline to the Red Sea ran through this city, and if the Somalis held Dire Dawa, Ethiopia would be unable to export its crops or bring in equipment needed to continue the fight. Gebre Tareke estimates the Somalis advanced with two motorized brigades, one tank battalion and one BM battery upon the city; against them were the Ethiopian Second Militia Division, the 201 Nebelbal battalion, 781 battalion of the 78th Brigade, the 4th Mechanized Company, and a tank platoon possessing two tanks.[39] The fighting was vicious as both sides knew what the stakes were, but after two days, despite that the Somalis had gained possession of the airport at one point, the Ethiopians had repulsed the assault, forcing the Somalis to withdraw. Henceforth, Dire Dawa was never at risk of attack.[40]

The greatest single victory of the SNA-WSLF was a second assault on Jijiga in mid-September (the Battle of Jijiga), in which the demoralized Ethiopian troops withdrew from the town. The local defenders were no match for the assaulting Somalis and the Ethiopian military was forced to withdraw past the strategic strongpoint of the Marda Pass, halfway between Jijiga and Harar. By September Ethiopia was forced to admit that it controlled only about 10% of the Ogaden and that the Ethiopian defenders had been pushed back into the non-Somali areas of Harerge, Bale, and Sidamo. However, the Somalis were unable to press their advantage because of the high attrition on its tank battalions, constant Ethiopian air attacks on their supply lines, and the onset of the rainy season which made the dirt roads unusable. During that time, the Ethiopian government managed to raise and train a giant militia force 100,000 strong and integrated it into the regular fighting force. Also, since the Ethiopian army was a client of U.S weapons, hasty acclimatization to the new Warsaw Pact bloc weaponry took place.

From October 1977 until January 1978, the SNA-WSLF forces attempted to capture Harar, where 40,000 Ethiopians had regrouped and re-armed with Soviet-supplied artillery and armor; backed by 1500 Soviet "advisors" and 11,000 Cuban soldiers, they engaged the attackers in vicious fighting. Though the Somali forces reached the city outskirts by November, they were too exhausted to take the city and eventually had to withdraw to await the Ethiopian counterattack.

The expected Ethiopian-Cuban attack occurred in early February; however, it was accompanied by a second attack that the Somalis did not expect. A column of Ethiopian and Cuban troops crossed northeast into the highlands between Jijiga and the border with Somalia, bypassing the SNA-WSLF force defending the Marda Pass. The attackers were thus able to assault from two directions in a "pincer" action, allowing the re-capture of Jijiga in only two days while killing 3,000 defenders. The Somali defense collapsed and every major Ethiopian town was recaptured in the following weeks. Recognizing that his position was untenable, Siad Barre ordered the SNA to retreat back into Somalia on 9 March 1978, although Rene LaFort claims that the Somalis, having foreseen the inevitable, had already withdrawn its heavy weapons.[41] The last significant Somali unit left Ethiopia on 15 March 1978, marking the end of the war.

Personnel

In July 1976, the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated the army consisted of 22,000 personnel, 6 tank battalions, 9 mechanised infantry battalions, 5 infantry battalions, 2 commando battalions, and 11 artillery battalions (5 anti-aircraft).[42] Two hundred T-34 and 50 T-54/55 main battle tanks had been estimated to have been delivered. The IISS emphasised that 'spares are short and not all equipment is serviceable.' The U.S. Army Area Handbook for Somalia, 1977 edition, agreed that the army comprised six tank and nine mechanised infantry battalions, but listed no infantry battalions, the two commando battalions, and 10 total artillery (five field and five anti-aircraft) battalions. (Kaplan et al., DA Pam 550-86, Second Edition, 1977, p. 315)

By 1987 the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency estimated the army was 40,000 strong.[43] The President, Mohamed Siad Barre, held the rank of Major General and acted as Minister of Defence. There were three vice-ministers of national defence. From the SNA headquarters in Mogadishu four sectors were directed: 26th Sector at Hargeisa, 54th Sector at Garowe, 21st Sector at Dusa Mareb, and 60th Sector at Baidoa. Thirteen divisions, averaging 3,300 strong, were divided between the four sectors – four in the northernmost and three in each of the other sectors. The sectors were under the command of brigadiers (three) and a colonel (one). Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan has been reported as 26th Sector commander from 1986 to 1988. Walter S. Clarke seemed to say that Barre's son [Maslah Siad] was commanding the 77th Sector in Mogadishu in November 1987.[44]

Structure

Somali Army

In March 2013 there were six trained brigades around Mogadishu, two of which were deployed at the time. Each brigade includes three to six battalions of around 1000 soldiers apiece, or 18,000 to 36,000 troops in total. Of these, an estimated 6,000 to 12,000 soldiers are currently in service.[45]

In February 2014, the Federal Government concluded a six-month training course for the first Commandos, Danab ("Lightning"), since 1991.[46] Training had been jointly carried out by Somali military experts and U.S. government personnel. The Army Chief of Staff Brigadier General Dahir Adan Elmi said that the new Commandos hail from different parts of the county. The Commandos will be headquartered at the former Balli Dogle air base (Walaweyn District, Lower Shebelle).[46] The training of the first Danab unit had begun in October 2013, and included 150 soldiers. As of July 2014, training of the second unit was underway. According to General Elmi, the special training is geared toward both urban and rural environments, and is aimed at preparing the soldiers for guerrilla warfare and all other types of modern military operations. Elmi said that a total of 570 Commandos are expected to have completed training by U.S. security personnel by the end of 2014.[47]

Somali Air Force

The Somali Air Force (SAF) was originally named the Somali Air Corps (SAC), and was established with Italian aid in the early 1960s. It emerged from the Italian "Corpo di Sicurezza della Somalia" that existed between 1950 and 1960, during the trusteeship period just prior to independence. The SAF's original equipment included eight North American F-51D Mustangs, Douglas C-47s and MiG 23s, which remained in service until 1968. The air force operated most of its aircraft from bases near Mogadishu, Hargeisa and Galkayo. An air defence force equipped with Soviet surface-to-air missiles and anti-aircraft guns was in existence by 1992.[48]

By January 1991 the air force was in ruins.[8] In 2012, Italy offered to help rebuild the air force.[49] In October 2014, Somali Air Force cadets underwent additional training in Turkey.[50]

On July 1 2015, the Somali Defence Minister Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini reopened the headquarter of the Somali Air Force. Located in Afisone, Mogadishu the move would facilitate the re-establishment of the air force after 25 years of civil war.[51]

According to CQ Press' Worldwide Government Directory with Intergovernmental Organizations, Somalia's reconstituted air force as of 2013 is led by Maj. Gen. Nur Ilmi Adawe.[1]

Somali Navy

The Somali Navy was formed after independence in 1960. Prior to 1991, it participated in several joint exercises with the United States, Great Britain and Canada. It disintegrated during the beginning of the civil war in Somalia, from the late 1980s.[10] In the 2000s (decade), the central government began the process of re-establishing the Somali Navy.[52]

On 30 June 2012, the United Arab Emirates announced a contribution of $1 million toward enhancing Somalia's naval security. Boats, equipment and communication gear necessary for the rebuilding of the coast guard would be bought. A central operations naval command was also planned to be set up in Mogadishu.[53]

Agreements

Somalia has signed military cooperation agreements with Turkey in May 2010,[54] February 2014,[55] and January 2015.[56]

In February 2012, Somali Prime Minister Abdiweli Mohamed Ali and Italian Defence Minister Gianpaolo Di Paola agreed that Italy would assist the Somali military as part of the National Security and Stabilization Plan (NSSP),[49] an initiative designed to strengthen and professionalize the national security forces.[57] The agreement would include training soldiers and rebuilding the Somali army.[49] In November 2014, the Federal Parliament approved a new defense and cooperation treaty with Italy, which the Ministry of Defence had signed earlier in the year. The agreement includes training and equipping of the army by Italy.[58]

In November 2014, Somalia signed a military cooperation agreement with the United Arab Emirates.[59]

Army equipment

Army equipment, 1981

The following were the Somali National Army's major weapons in 1981:[5]

Army equipment, 1989

Previous arms acquisitions included the following equipment, much of which was unserviceable ca. June 1989:[60] 293 main battle tanks (30 Centurion from Kuwait[61] 123 M47 Patton, 30 T-34, 110 T-54/55 from various sources). Other armoured fighting vehicles included 10 M41 Walker Bulldog light tanks, 30 BRDM-2 and 15 Panhard AML-90 armored cars (formerly owned by Saudi Arabia). The IISS estimated in 1989 that there were 474 armoured personnel carriers, including 64 BTR-40/BTR-50/BTR-60, 100 BTR-152 wheeled armored personnel carriers, 310 Fiat 6614 and 6616s, and that BMR-600s had been reported. The IISS estimated that there were 210 towed artillery pieces (8 M-1944 100mm, 100 M-56 105mm, 84 M-1938 122mm, and 18 M198 155 mm towed howitzers). Other equipment reported by the IISS included 82mm and 120mm mortars, 100 Milan and BGM-71 TOW anti-tank guided missiles, rocket launchers, recoilless rifles, and a variety of Soviet air defence guns of 20mm, 23mm, 37mm, 40mm, 57mm, and 100mm calibre. As of 1 June 1989, the IISS also estimated that Somali army surface-to-air defense equipment included 40 SA-2 Guideline missiles (operational status uncertain), 10 SA-3 Goa, and 20 SA-7 surface-to-air missiles.[60]

Army equipment, 2012-2015

In May 2012, over thirty-three vehicles were donated by the U.S. government to the SNA. The vehicles include 16 Magirus Trucks, 4 Hilux Pickups, 6 Land Cruiser Pickups, 1 Water Tanker, and 6 Water Trailers.[62] On 9 April 2013, the U.S. government approved the provision of defense articles and services by the American authorities to the Somali Federal Government.[63] It handed over 15 vehicles to the new Commandos in March 2014.[64]

In April 2013, Djibouti presented the SNA with 15 armoured military vehicles. The equipment was part of a larger consignment of 25 military trucks and 25 armoured military vehicles.[65]

The same month, the Italian government handed over 54 armored and personnel carrier vehicles to the army at a ceremony in Mogadishu.[66]

As of April 2015, the Ministry of Defence's Guulwade Plan identifies the equipment and weaponry requirements of the army.[67]

Leadership

Minister of Defence

| Name | Tenure | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini | 27 January 2015 – Present | Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) |

| Mohamed Sheikh Hassan | 17 January 2014 – 27 January 2015 | Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) |

| Abdihakim Mohamoud Haji-Faqi | 4 November 2012 – 17 January 2014 | Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) |

| Hussein Arab Isse | 20 July 2011 – 4 November 2012 | Transitional Federal Government (TFG) |

| Abdihakim Mohamoud Haji-Faqi | 12 November 2010 – 20 July 2011 | Transitional Federal Government (TFG) |

| Mohamed Abdi Mohamed | 21 February 2009 – 12 November 2010 | Transitional Federal Government (TFG) |

| Aden Abdullahi Nur | 1986 – 1988 | Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP) |

| Muhammad Ali Samatar | 1980 – 1986 | Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP) |

Chief of Army

| Name | Took command | Left command |

|---|---|---|

| Maj. Gen Ismail Qasim Naji | 14 April 2005[68] | 10 February 2007[69] |

| Maj. Gen Abdullahi Ali Omar | 10 February 2007[69] | 21 July 2007[70] |

| Brig. Gen Salah Hassan Jama | 21 July 2007[70] | 11 June 2008[71] |

| Maj. Gen Said Dheere Mohamed | 11 June 2008[71] | 15 May 2009[72] |

| Maj. Gen Yusuf Osman Dhumal | 15 May 2009[72] | 10 December 2009[73] |

| Brig. Gen Mohamed Gelle Kahiye | 6 December 2009[73] | 18 September 2010[74] |

| Brig. Gen Ahmed Jimale Gedi | 18 September 2010 | 28 March 2011 |

| Maj. Gen Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini | 28 March 2011[75] | 13 March 2013[76] |

| Brig. Gen Dahir Adan Elmi | 13 March 2013[76] | 3 September 2015 (S/2015/801, p. 24) |

| Maj. Gen Mahamed Aadan Ahmed | -- - 2015[76] | continue (S/2015/802, p. 24) |

Military ranks

In July 2014, General Dahir Adan Elmi announced the completion of a review of the Somali National Army ranks. The SNA in conjunction with the Ministry of Defense is also slated to standardize the martial ranking system and eliminate any unauthorized promotions as part of a broader reform.[77]

As of 1977, Somalia's army ranks were as follows:[5]

Notes

- ^ a b c d Martino, John (2013). Worldwide Government Directory with Intergovernmental Organizations 2013. CQ Press. p. 1462. ISBN 1452299374.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Fsijmriswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "The Federal Republic of Somalia – Provisional Constitution" (PDF). Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "The Federal Republic of Somalia – Provisional Constitution". Retrieved 13 March 2013. Chapter 14, Article 126(3).

- ^ a b c "Somalia: A Country Study – Chapter 5: National Security" (PDF). Library of Congress. c. 1981. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ See discussion in Abdullah A. Mohamoud, State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa : the case of Somalia (1960–2001). West Lafayette, Ind. : Purdue University Press, c2006

- ^ Daniel Compagnon, 'Political decay in Somalia: From Personal Rule to Warlordism,' Refuge, Vol 12, No. 5, November–December 1992, 9.

- ^ a b Nina J. Fitzgerald, Somalia: issues, history, and bibliography, (Nova Publishers: 2002), p.19.

- ^ "SOMALIA PM Said "Cabinet will work tirelessly for the people of Somalia"". Midnimo. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Library of Congress Country Study, Somalia, The Warrior Tradition and Development of a Modern Army, research complete May 1992.

- ^ Saheed A. Adejumobi, The History of Ethiopia, (Greenwood Press: 2006), p.178

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc, Encyclopedia Britannica, Volume 1, (Encyclopaedia Britannica: 2005), p.163

- ^ David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State (Boulder: Westview Press, 1987).

- ^ Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792 By Jeremy Black pg 9

- ^ W. Mitchell. Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Whitehall Yard, Volume 57, Issue 2. p. 997.

- ^ William James Makin. War Over Ethiopia. p. 227.

- ^ "Puntland Forces mark 50th anniversary of Somali Armed". Garowe Online. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, (Encyclopaedia Britannica: 2002), p. 835

- ^ "The dawn of the Somali nation-state in 1960". Buluugleey.com. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ A transcript of a Reuters report of June 26, 1960 says that, during the independence ceremony for Somaliland “..Nearly 1,000 British-trained Somaliland Scouts were then handed over to the Prime Minister by Brigadier O. G. Brooks, the Colonel Commandant.” http://www.slnnews.com/2015/06/somaliland-independence-26th-june-1960-the-world-press/

- ^ Library of Congress Country Study, Somalia, Manpower, Training, and Conditions of Service (Thomas Ofcansky), research complete May 1992.

- ^ Africa Watch Committee, Kenya: Taking Liberties, (Yale University Press: 1991), p.269

- ^ Women's Rights Project, The Human Rights Watch Global Report on Women's Human Rights, (Yale University Press: 1995), p.121

- ^ Francis Vallat, First report on succession of states in respect of treaties: International Law Commission twenty-sixth session 6 May-26 July 1974, (United Nations: 1974), p.20

- ^ a b "The Somali Dispute: Kenya Beware" by Maj. Tom Wanambisi for the Marine Corps Command and Staff College, April 6, 1984 (hosted by globalsecurity.org)

- ^ Hogg, Richard (1986). "The New Pastoralism: Poverty and Dependency in Northern Kenya". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 56 (3): 319–333. JSTOR 1160687.

- ^ Howell, John (May 1968). "An Analysis of Kenyan Foreign Policy". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 6 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00016657. JSTOR 158675.

- ^ a b c Colin Legum, John Drysdale, Africa contemporary record: annual survey and documents, Volume 2, (Africa Research Limited., 1970), p.B-174.

- ^ a b Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p.290.

- ^ Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Richard Ford (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56902-073-6.

- ^ J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 8, (Cambridge University Press: 1985), p.478.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac, Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p.214.

- ^ Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Coup d'Etat", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, retrieved 21 October 2009

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy, (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p.279.

- ^ Oliver Ramsbotham, Tom Woodhouse, Encyclopedia of international peacekeeping operations, (ABC-CLIO: 1999), p.222.

- ^ a b Gebru Tareke, "Ethiopia-Somalia War," p. 644

- ^ Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978 by Mark Urban pg 42

- ^ "Ethiopia: East Germany". Library of Congress. 8 November 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ^ Gebru Tareke, "Ethiopia-Somalia War," p. 645.

- ^ Gebru Tareke, "Ethiopia-Somalia War", p. 646

- ^ Rene LaFort, Ethiopia: An Heretical Revolution?, translated by A.M. Berrett (London: Zed Press, 1983), p. 260

- ^ IISS Military Balance 1976–77, p.44

- ^ Defense Intelligence Agency, 'Military Intelligence Summary, Vol IV, Part III, Africa South of the Sahara', November 1987, 12

- ^ Walter S. Clarke, Background Information for Operation Restore Hope, Strategic Studies Institute, p. 27.

- ^ Kwayera, Juma (9 March 2013). "Hope alive in Somalia as UN partially lifts arms embargo". Standard Digital. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ a b Mohyaddin, Shafi’i (8 February 2014). "Somalia trains its first commandos after the collapse of the central government". Hiiraan Online. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Dan Joseph, Harun Maruf (31 July 2014). "US-Trained Somali Commandos Fight Al-Shabab". VOA. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Somalia, A Country Study, 1992/3, 205.

- ^ a b c "PM meets Italian Defence minister, IFAD director and addressed Rome 3 students". Laanta. 2 February 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Somali air force cadets in Turkey". Somalia Newsroom. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Somalia Reopens Air Force Headquarter". Goobjoog News. 1 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Somalia to Make Task Marine Forces to Secure Its Coast". Shabelle Media Network. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "UAE committed to contribute US$1 million to support Somali naval security capabilities, says Gargash". UAE Interact. 30 June 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Turkey-Somalia military agreement approved". Today's Zaman. 9 November 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ "SOMALIA: Ministry of Defense signs an agreement of military support with Turkish Defense ministry". Raxanreeb. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Press Release: Erdogan's Somalia Visit". Goobjoog. 25 January 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ "Press Release: AMISOM offers IHL training to senior officials of the Somali National Forces". AMISOM. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ "SOMALIA: Parliament approves Somalia's military treaty with Italy". Raxanreeb. 4 November 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "UAE, Somalia sign military cooperation agreement". Kuwait News Agency. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ a b IISS Military Balance 1989–90, Brassey's for the IISS, 1989, 113.

- ^ "Arms Trade Register". SIPRI. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ "PRESS RELEASE: AMISOM hands over military vehicles to the Somali National Army". AMISOM. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "U.S. eases arms restrictions for Somalia". UPI. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "SOMALIA: U.S donates military vehicles to newly trained Somali Commandos". Raxanreeb. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Djibouti donates armoured vehicles to Somalia". Sabahi. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Italy Hands over Military Consignment to Somali Government". Goobjoog. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Urotsgosmtfwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Somali cabinet fills key posts". Al-Jazeera. 14 April 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Ssacsanaaawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Peaceful day for Somalia reconciliation conference" garoweonline.com

- ^ a b "Somalia's Interim President Appoints New Chief of Staff for the Armed Forces" hiiraan.com

- ^ a b "Somali president names new military chief amid insurgent push" topnews.in

- ^ a b "Somalia fires heads of police force and military" reuters.com

- ^ "Somali president fires top commanders" hiiraan.com

- ^ "Salad Gabeyre Kediye Was a Brigadier General In The Somali Military And A Revolutionary". Banaadir Weyne. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ a b c "Somalia changes its top military commanders". Shabelle Media Network. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Somalia: Military Chief warns counterfeit military ranks". Raxanreeb. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

References

- Defense Intelligence Agency, 'Military Intelligence Summary, Vol IV, Part III, Africa South of the Sahara', November 1987

- International Crisis Group, Somalia: The Transitional Government on Life Support, Africa Report 170, 20 February 2011.

- Human Rights Watch, Human Rights Abuses by Transitional Federal Government Forces in 'So Much to Fear: War Crimes and Devastation in Somalia', December 2008

- Library of Congress Somalia Country Study 1992

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud, State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa : the case of Somalia (1960–2001). West Lafayette, Ind. : Purdue University Press, c2006 (DT407 M697 S).

- Williams, Paul D. "Into the Mogadishu maelstrom: the African Union mission in Somalia." International Peacekeeping 16.4 (2009): 514–530.

Further reading

- Adam, Hussein M. "Somalia: Personal Rule, Military Rule and Militarism." The Military and Militarism in Africa, Dakar: CODESRIA (1998): 355-97.

- Brian Crozier, The Soviet Presence in Somalia, Institute for the Study of Conflict, London, 1975

- Irving Kaplan, Area Handbook for Somalia, American University, 1969 and 1977.

- Nilsson, Claes, and Johan Norberg, "European Union Training Mission Somalia: A Mission Assessment", Swedish National Defence Research Institute, 2014.

- Baffour Agyeman-Duah, The Horn of Africa: Conflict, Demilitarization and Reconstruction, Journal of Conflict Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1996, accessed at https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/JCS/article/view/11813/12632#a50

External links

- Anderson, Jon Lee (14 December 2009). "The Most Failed State". The New Yorker. Retrieved 18 May 2015. - includes notes on state of Somali Navy

- Air Combat Information Group, Somalia, 1980–1996

- "Weapons at War", a World Policy Institute Issue Brief by William D. Hartung, , May 1995, chapter III: Strengthening Potential Adversaries (12th paragraph), Somalia.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.