Ingush people

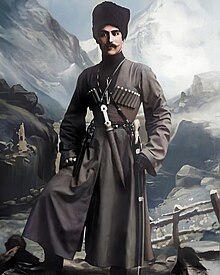

Ingush. Early 20th century. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ± 700,000 [1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 536,357 | |

| | 507 061[3][4] |

| | 1,296 |

| | 28 336[5] |

| 16,893 | |

| 455 | |

| Languages | |

| Ingush | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam (Shafii Madhhab) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chechens, Bats, Kists and other Northeast Caucasian peoples | |

The Ingush (/ˈɪŋɡʊʃ/, Ingush: ГIалгIай, Ghalghaj, pronounced Template:IPA-cau), historically also referred to as Kisti,[6] are a Northeast Caucasian native ethnic group of the North Caucasus, mostly inhabiting their native Ingushetia, a federal republic of Russian Federation. The Ingush are predominantly Sunni Muslims and speak the Ingush language, a Northeast Caucasian language that is closely related to Chechen; the two form a dialect continuum.[7] The Ingush and Chechen peoples are collectively known as the Vainakh.

History

The Ingush people have been historically mentioned under many different names, such as Dzurdzuks, Kists or Ghlighvi[8][9], although none of them was used as an ethnonym. The ancient Greek historian Strabo wrote about the Gelians, an unknown people in the Caucasus[10], which the American cartographer Joseph Hutchins Colton later used for the Vainakh people in his map from 1856.[11] Contemporary sources mention the ethnonym Nakhchoy, which was used by the Chechens as well.[12] The ethnonym Nakhchoy was replaced by the word Vainakh starting from the 1930s.[13]

In 1770, the elders of 24 Ingush tribes signed a treaty with Russia,[14] but are commonly considered under Russian rule from 1810. Under Soviet rule during World War II the Ingush, along with the Chechens were falsely accused of collaborating with the Nazis and thus, the entire population was deported to the Kazakh and Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republics. The Ingush were rehabilitated in the 1950s, after the death of Joseph Stalin, and allowed to return home in 1957, though by that time western Ingush lands had been ceded to North Ossetia.

Architecture

The famous Soviet archaeologist and historian, professor E.I. Krupnov described the Ingush towers in his work «Medieval Ingushetia»[15]:

«Ingush battle towers are in the true sense the pinnacle of the architectural and constructional mastery of the ancient population of the region. Striking in their simplicity of form, monumentality and strict grace. For their time, the Ingush towers were a true miracle of human genius.»

Culture

The Ingush possess a varied culture of traditions, legends, epics, tales, songs, proverbs, and sayings. Music, songs and dance are particularly highly regarded. Popular musical instruments include the dachick-panderr (a kind of balalaika), kekhat ponder (accordion, generally played by girls), mirz ponder (a three-stringed violin), zurna (a type of oboe), tambourine, and drums.

Religion

The Ingush are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Shāfi‘ī Madh'hab, with a Sufi background.[16]

Ingush genetics

The Caucasus populations exhibit, on average, less variability than other populations for the eight Alu insertion poly-morphisms analysed here. The average heterozygosity is less than that for any other region of the world, with the exception of Sahul. Within the Caucasus, Ingushians have much lower levels of variability than any of the other populations. The Ingushians also showed unusual patterns of mtDNA variation when compared with other Caucasus populations (Nasidze and Stoneking, submitted), which indicates that some feature of the Ingushian population history, or of this particular sample of Ingushians, must be responsible for their different patterns of genetic variation at both mtDNA and the Alu insertion loci.[17][18]

— European Journal of Human Genetics, 2001

According to one test by Nasidze in 2003 (analyzed further in 2004), the Y-chromosome structure of the Ingush greatly resembled that of neighboring Caucasian populations (especially Chechens, their linguistic and cultural brethren).[19][20]

There has been only one notable study on the Ingush Y chromosome. These following statistics should not be regarded as final, as Nasidze's test had a notably low sample data for the Ingush. However, they do give an idea of the main haplogroups of the Ingush.

- J2 – 89% of Ingush have the highest reported frequency of J2 which is associated with the Fertile Crescent.[21]

- F* – (11% of Ingush)[20] This haplogroup was called "F*" by Nasidze. It may have actually been any haplogroup under F that was not under G, I, J2, or K; however, it is probably consists of haplotypes that are either under J1 (typical of the region, with very high frequencies in parts of Dagestan, as well as Arabia, albeit in a different subclade) or F3.

- G – (27% of Ingush)[20] Typical of the Middle East, the Mediterranean and the Caucasus. The highest values were found among Georgians, Circassians and Ossetes. There was a noticeable difference in G between Ingush and Chechens (in J2 and F*, Ingush and Chechens have similar levels), possibly attributable to low samples that were all from the same town.

In the mtDNA, the Ingush formed a more clearly distinct population, with distance from other populations. The closest in an analysis by Nasidze were Chechens, Kabardins and Adyghe (Circassians), but these were all much closer to other populations than they were to the Ingush.[20]

See also

References

- ^ "Russia Beyond. «Люди башен»: Как живут Ингуши".

- ^ "Экспедиция ТВ2 в Республику Ингушетия".

- ^ "Население Республики Ингушетия (2020)".

- ^ "Росстат. Демография: Численность постоянного населения в среднем за год (2019)".

- ^ "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г. Национальный состав регионов России".

- ^ Sir Richard Phillips. A Geographical View of the World. New York, 1826-1833.

- ^ Nichols, J. and Vagapov, A. D. (2004). Chechen-English and English-Chechen Dictionary, p. 4. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-31594-8.

- ^ Heinrich Julius Klaproth. "Inguschen-Ghalgha (Khißt-Ghlighwa)" Geographisch-historische Beschreibung des östlichen Kaukasus, zwischen den Flüssen Terek, Aragwi, Kur und dem Kaspischen Meere Pt.2 of Volume 50, Bibliothek der neuesten und wichtigsten Reisebeschreibungen zur Erweiterung der Erdkunde nach einem systematischen Plane bearbeitet, und in Verbindung mit einigen andern Gelehrten bearbeitet und hrsg. von M.C. Sprengel, 1800-1814.

- ^ Dietrich Christoph von Rommel. "Kisten (Inguschen)" Die Völker des Caucasus nach den Berichten der Reisebeschreiber Volume 1 van Aus dem Archiv für Ethnographie und Linguistik. Verlage des Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, 1808. Oxford University.

- ^ Karl H.E. Koch. Durch Russland Nach Dem Kaukasischen Isthmus in Den Jahern 1836, 1837 Und 1838

- ^ J.H. Colton. "Gelia" Turkey In Asia And The Caucasian Provinces Of Russia. 1856.

- ^ Берже, А.П. (1859). Чечня и Чеченцы. pp. 65–66.

- ^ Шнирельман, В. А. Быть аланами. Интеллектуалы и политика на Северном Кавказе в XX веке. — М.: Новое литературное обозрение. p. 279.

- ^ Johann Anton Güldenstädt. «Travels through Russia and the Caucasus Mountains». Vol. 1, 1787

- ^ Крупнов Е.И. 1971.

- ^ Stefano Allievi; Jørgen S. Nielsen (2003). Muslim networks and transnational communities in and across Europe. Vol. 1.

- ^ Ivane Nasidze; et al. (2001). "Alu insertion polymorphisms and the genetic structure of human populations from the Caucasus". European Journal of Human Genetics. 9 (4): 267–272. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200615. PMID 11313770.

- ^ Nasidze, I; Risch, GM; Robichaux, M; Sherry, ST; Batzer, MA; Stoneking, M (April 2001). "Alu insertion polymorphisms and the genetic structure of human populations from the Caucasus" (PDF). Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 9 (4): 267–72. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200615. PMID 11313770.

- ^ Nasidze I, Sarkisian T, Kerimov A, Stoneking M (March 2003). "Testing hypotheses of language replacement in the Caucasus: evidence from the Y-chromosome" (PDF). Human Genetics. 112 (3): 255–61. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0874-4. PMID 12596050. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-27. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ^ a b c d Nasidze, I.; Ling, E. Y. S.; Quinque, D.; et al. (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA and Y-Chromosome Variation in the Caucasus" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (3): 205–221. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00092.x. PMID 15180701. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-08.

- ^ Oleg Balanovsky, Khadizhat Dibirova, Anna Dybo, Oleg Mudrak, Svetlana Frolova, Elvira Pocheshkhova, Marc Haber, Daniel Platt, Theodore Schurr, Wolfgang Haak, Marina Kuznetsova, Magomed Radzhabov, Olga Balaganskaya, Alexey Romanov, Tatiana Zakharova, David F. Soria Hernanz, Pierre Zalloua, Sergey Koshel, Merritt Ruhlen, Colin Renfrew, R. Spencer Wells, Chris Tyler-Smith, Elena Balanovska, and The Genographic Consortium Parallel Evolution of Genes and Languages in the Caucasus Region Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011 : msr126v1-msr126.