Abraham Lincoln: Difference between revisions

→Emancipation Proclamation: as areas were taken, slaves were freed |

|||

| Line 208: | Line 208: | ||

Only Robert survived into adulthood. Of Robert's children, only Jessie Lincoln had any children (2 - Mary Lincoln Beckwith and Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith). Neither Robert Beckwith nor Mary Beckwith had any children, so Abraham Lincoln's bloodline ended when Robert Beckwith (Lincoln's great-grandson) died on [[December 24]], [[1985]]. |

Only Robert survived into adulthood. Of Robert's children, only Jessie Lincoln had any children (2 - Mary Lincoln Beckwith and Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith). Neither Robert Beckwith nor Mary Beckwith had any children, so Abraham Lincoln's bloodline ended when Robert Beckwith (Lincoln's great-grandson) died on [[December 24]], [[1985]]. |

||

[http://members.aol.com/beaufait/biography/geneology.htm] |

[http://members.aol.com/beaufait/biography/geneology.htm] |

||

==Lincoln's sexuality== |

|||

Abraham Lincoln is known to have lived for four years with [[Joshua Speed]], when both men were in their twenties. They shared a bed during these years and developed a friendship that would last until their deaths. A number of biographers, beginning with [[Carl Sandburg]] in [[1926]], have suggested or implied that this relationship was [[homosexual]], though others have argued that Lincoln and Speed shared a bed purely because of their poor financial circumstances. When Speed left Lincoln and returned to [[Kentucky]] after their four years of cohabitation, Lincoln is believed to have suffered something approaching a [[nervous breakdown]]. He displayed remarkable intimacy and affection in his correspondence with Speed, more so even than in his correspondence with his wife. |

|||

Lincoln shared beds with several other men during his life. Amongst these was an army officer, [[David Derickson]], assigned to Lincoln's bodyguard in [[1862]]. Several sources characterise the relationship between the two as intimiate, and it was the subject of gossip in [[Washington, DC|Washington]] at the time. They shared a bed during the absences of Lincoln's wife, until Derickson was promoted in [[1863]]. Again, some biographers have interpreted this as a homosexual affair. A recent study has also pointed to homosexual themes in bawdy poetry written by the teenage Lincoln, especially a poem in which a boy marries another boy. |

|||

==Lincoln exhumed== |

==Lincoln exhumed== |

||

Revision as of 13:21, 17 December 2004

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

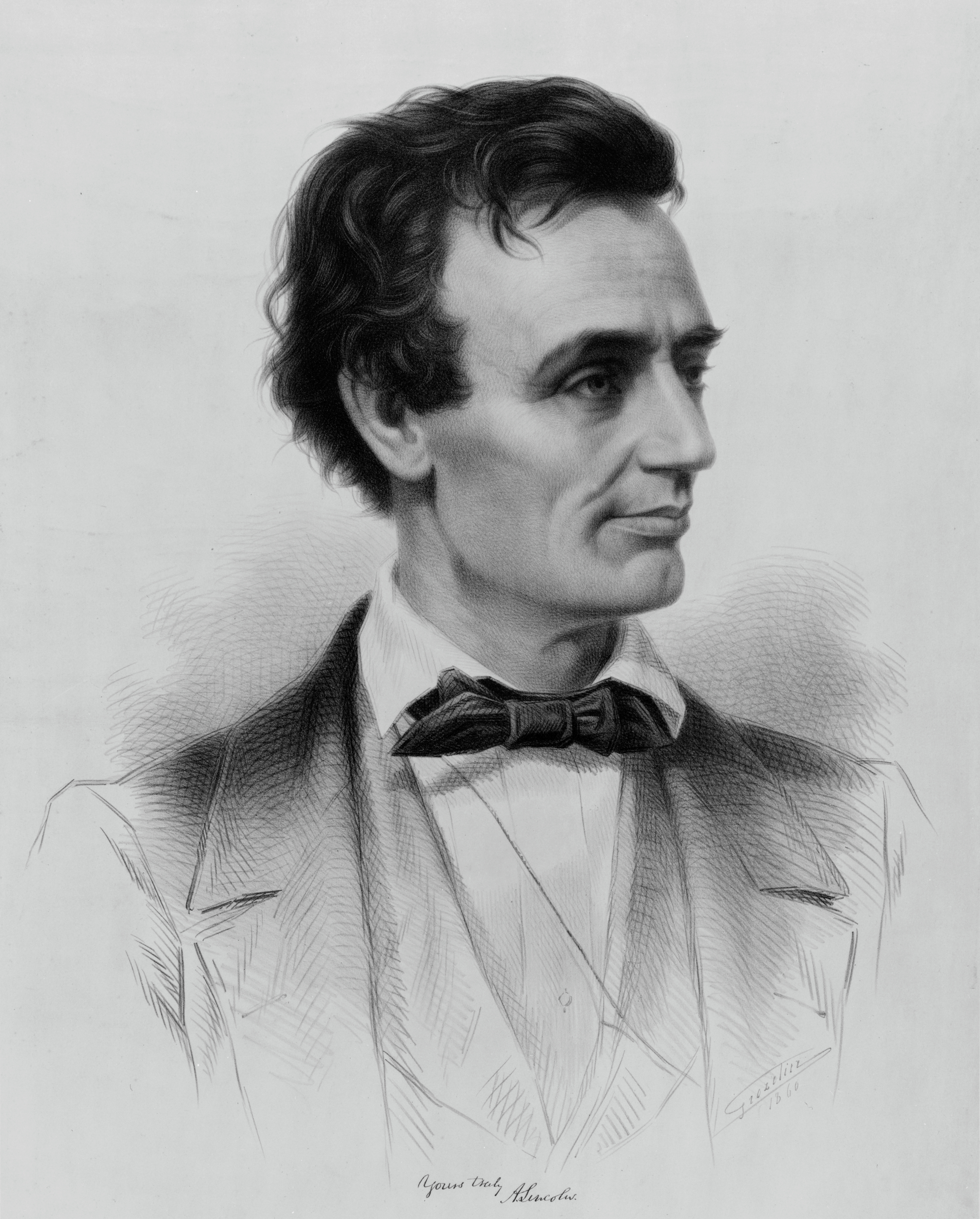

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809–April 15, 1865), sometimes called Abe Lincoln and nicknamed Honest Abe, the Rail Splitter, and the Great Emancipator, was the 16th (1861-1865) President of the United States, and the first president from the Republican Party.

The election of Lincoln, who staunchly opposed the expansion of slavery, polarized the nation, and soon led to the Civil War. During the war, Lincoln assumed more power than any previous president in U.S. history. Taking a broad view of the president's war powers, he proclaimed a blockade, suspended the writ of habeas corpus for anti-Union activity, spent money without congressional authorization, and personally directed the war effort, which ultimately led the Union forces to victory over the rebel Confederacy.

Lincoln was an extremely deft politician who emerged as a wartime leader skilled at balancing competing considerations and adept at getting rival groups to work together toward a common goal. His leadership qualities were evident in his handling of the border slave states at the beginning of the fighting, in his defeat of a congressional attempt to reorganize his cabinet in 1862, and in his defusing of the peace issue in the 1864 presidential campaign.

Lincoln had a lasting influence on U.S. political institutions. The most important was setting the precedent of sweeping executive powers in a time of national emergency. Lincoln was also the president who declared Thanksgiving as a national holiday, established the U.S Department of Agriculture (though not as a Cabinet-level department), created national banking and banks, and admitted Nebraska and West Virginia as states. His assassination, shortly after the end of the Civil War, made him something of a martyr. His reputation was forever sealed by the victory that he won, but without the tarnishing that could have resulted from the disorder of Reconstruction in the aftermath of the war. He is widely considered to be the greatest U.S. president.

Early life

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, coincidentally on the the same day as Charles Darwin, in a one-room log cabin on a farm in Hardin County, Kentucky (now in LaRue Co., in Nolin Creek, three miles (5 km) south of the town of Hodgenville), to Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. Lincoln was named after his deceased grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, who was murdered by Native Americans. Lincoln's parents were largely uneducated. When Abraham Lincoln was seven years old, he and his parents moved to Spencer County, Indiana, "partly on account of slavery" and partly because of economic difficulty in Kentucky. In 1830, after economic and land-title difficulties in Indiana, the family settled on government land along the Sangamon River on a site selected by Lincoln's father in Macon County, Illinois, near the present city of Decatur. The following winter was especially brutal, and the family nearly moved back to Indiana. When his father relocated the family to a nearby site the following year, the 22-year-old Lincoln struck out on his own, canoeing down the Sangamon to homestead on his own in Sangamon County, Illinois (now in Menard County), in the village of New Salem. Later that year, hired by New Salem businessman Denton Offutt and accompanied by friends, he took goods from New Salem to New Orleans via flatboat on the Sangamon, Illinois and Mississippi rivers. While in New Orleans he may have witnessed a slave auction that left an indelible impression on him for the rest of his life.

Lincoln began his political career in 1832 with a campaign for the Illinois General Assembly. The centerpiece of his platform was the undertaking of navigational improvements on the Sangamon in the hopes of attracting steamboat traffic to the river, which would allow sparsely populated, poor areas along and near the river to grow and prosper. He served as a captain in a company of the Illinois militia drawn from New Salem during the Black Hawk War, writing after being elected by his peers that he had not had "any such success in life which gave him so much satisfaction." He later tried his hand at several business and political ventures, and failed at them. Finally, after coming across the second volume of Sir William Blackstone's four-volume Commentaries on the Laws of England, he taught himself the law, and was admitted to the Illinois Bar in 1837. That same year, he moved to Springfield, Illinois and began to practice law with Stephen T. Logan. Later, he partnered with Willam H. Herndon. He became one of the most highly respected and successful lawyers in the state of Illinois, and became steadily more prosperous. Lincoln served four successive terms in the Illinois House of Representatives, as a representative from Sangamon County, beginning in 1834. In 1837 he made his first protest against slavery in the Illinois House, stating that the institution was "founded on both injustice and bad policy." [1] In 1846 he was elected to one term in the House of Representatives.

Early political career

While in the House of Representatives, Lincoln spent most of his time in Washington, DC alone, and made a less than spectacular impression on his fellow politicians. He used his office as an opportunity to speak out against the war with Mexico, which he attributed to President Polk's desire for "military glory -- that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood."

When his term ended, the incoming Taylor administration offered him the governorship of the Oregon Territory. He declined, returning instead to Springfield, Illinois where, although he remained active in Whig Party affairs in the state, he turned most of his energies to making a living at the bar.

Law practice

Lincoln acquired prominence in Illinois legal circles by the mid 1850s, especially through his involvement in litigation involving competing transportation interests — both the river barges and the railroads.

He represented the Alton & Sangamon Railroad, for example, in an 1851 dispute with one of its shareholders, James A. Barret. Barret had refused to pay the balance on his pledge to that corporation on the ground that it had changed its originally planned route.

Lincoln argued that as a matter of law a corporation is not bound by its original charter when that charter can be amended in the public interest, that the newer proposed Alton & Sangamon route was superior and less expensive, and that accordingly the corporation had a right to sue Mr. Barret for his delinquent payment. He won this case, and the decision by the Illinois Supreme Court was eventually cited by several other courts throughout the United States.

Another important example of Lincoln's skills as a railroad lawyer was a lawsuit over a tax exemption that the state granted to the Illinois Central Railroad. McLean County argued that the state had no authority to grant such an exemption, and it sought to impose taxes on the railroad notwithstanding. In January 1856, the Illinois Supreme Court delivered its opinion upholding the tax exemption, accepting Lincoln's arguments.

Toward the Presidency

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which opened the named territories to slavery - thus erasing the limits on slavery's spread which had been part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 - also helped draw Lincoln back into electoral politics. It was a speech against Kansas-Nebraska, on October 16, 1854 in Peoria, that caused Lincoln to stand out among the other free-soil orators of the day.

During his unsuccessful 1858 campaign for the United States Senate against Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln debated Douglas in a series of events which represented a national discussion on the issues that were about to split the nation in two. The Lincoln-Douglas debates drew national attention toward the two men, bringing both men the prominence that allowed them to be nominated by their parties for the Presidential election of 1860. On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States, the first Republican to hold that office.

Shortly after his election, the South made it clear that secession was inevitable, which greatly increased tension across the nation. President-elect Lincoln survived an assassination attempt in Baltimore, Maryland, and on February 23, 1861 arrived secretly in disguise to Washington, DC. The South ridiculed Lincoln for this seemingly cowardly act, but the efforts at security may have been prudent.

Presidency

At Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, 1861, the Turners formed Lincoln's bodyguard; and a sizable garrison of federal troops was also present, ready to protect the president and the capital from rebel invasion. In his address (paragraph 29), Lincoln said, "This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing Government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it." [2]

Lincoln on Slavery

Lincoln's actual position on freeing enslaved African-Americans is controversial today, despite the frequency and clarity with which he stated it both before his election to president (i.e. Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858) and after (see Lincoln's First Inaugural). He stated his position forcefully and succinctly in a letter to Horace Greeley of August 22, 1862.

- I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was." If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

- I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

However, at the time of the writing this letter, Lincoln was already leaning towards emancipation, which would lead to the Emancipation Proclamation.

Also revealing was his letter a year later to James Conkling of August 26, 1863, which included the following excerpt:

- There was more than a year and a half of trial to suppress the rebellion before the proclamation issued, the last one hundred days of which passed under an explicit notice that it was coming, unless averted by those in revolt, returning to their allegiance. The war has certainly progressed as favorably for us, since the issue of proclamation as before. I know, as fully as one can know the opinions of others, that some of the commanders of our armies in the field who have given us our most important successes believe the emancipation policy and the use of the colored troops constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the Rebellion, and that at least one of these important successes could not have been achieved when it was but for the aid of black soldiers. Among the commanders holding these views are some who have never had any affinity with what is called abolitionism or with the Republican party policies but who held them purely as military opinions. I submit these opinions as being entitled to some weight against the objections often urged that emancipation and arming the blacks are unwise as military measures and were not adopted as such in good faith.

- You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then exclusively to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistance to the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be an apt time, then, for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes.

- I thought that in your struggle for the Union, to whatever extent the negroes should cease helping the enemy, to that extent it weakened the enemy in his resistance to you. Do you think differently? I thought that whatever negroes can be got to do as soldiers, leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do, in saving the Union. Does it appear otherwise to you? But negroes, like other people, act upon motives. Why should they do any thing for us, if we will do nothing for them? If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept.

Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln is often credited with freeing enslaved African-Americans with the Emancipation Proclamation, though in practice this only freed the slaves in areas of the Confederacy as those areas came under control of Union forces; in occupied and northern territories that still allowed slavery, slaves were not freed. The proclamation made abolishing slavery in the rebel states an official war goal and it did become the impetus for the enactment of the 13th and 14th Amendments of the United States Constitution which respectively abolished slavery and established the federal enforcement of civil rights. Politically, the Emancipation Proclamation did much to help the Northern cause; Lincoln's strong abolitionist stand finally convinced Britain that the United States was a democracy working for good, and as a result Britain declined to assist the South.

Gettysburg Address

Despite his meager education and “backwoods” upbringing, Lincoln possessed an extraordinary command of the English language, as evidenced by the Gettysburg Address, a speech dedicating a cemetery of Union soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. While most of the speakers—e.g. Edward Everett—at the event spoke at length, some for hours, Lincoln's few choice words resonated across the nation and across history, defying Lincoln's own prediction that "The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here." While there is little documentation of the other speeches of the day, Lincoln's address is regarded as one of the great speeches in history. At the time, however, it was generally disregarded. Its prominence in American history developed later, as the short speech was often used by teachers as one of reasonable length to force students to memorize. Lincoln's second inaugural address is also greatly admired and often quoted.

The Civil War

The war was a source of constant frustration for the president, and it occupied nearly all of his time. After repeated difficulties with General George McClellan and a string of other unsuccessful commanding generals, Lincoln made the fateful decision to appoint a radical and somewhat scandalous army commander: General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant would apply his military knowledge and leadership talents to bring about the close of the Civil War.

When Richmond, the Confederate capital, was at long last captured, Lincoln went there to make a public gesture of sitting at Jefferson Davis's own desk, symbolically saying to the nation that the President of the United States held authority over the entire land. He was greeted at the city as a conquering hero by freed slaves, whose sentiments were epitomized by one admirer's quote, "I know I am free for I have seen the face of Father Abraham and have felt him."

The reconstruction of the Union weighed heavy on the President's mind. He was determined to take a course that would not permanently alienate the former Confederate states. "Let 'em up easy," he told his assembled military leaders Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Gen. William T. Sherman and Adm. David Dixon Porter in an 1865 meeting on the steamer River Queen.

In 1864, Lincoln was the first and only President to face a presidential election during a civil war. The long war and the issue of emancipation appeared to be severely hampering his prospects and an electoral defeat appeared likely against the Democratic nominee and former general, George McClellan. However, a series of timely Union victories shortly before election day changed the situation dramatically and Lincoln was reelected.

During the Civil War, Lincoln held powers no previous president had wielded; he suspended the writ of habeas corpus and frequently imprisoned Southern spies and sympathizers without trial. On the other hand, he often commuted executions.

Just days before Lincoln's assassination, the war ended with Union victory on April 9, 1865, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. The defeat of the Confederacy paved the way for the abolishment of slavery in the United States.

Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Abraham Lincoln | 1861–1865 |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin | 1861–1865 |

| Andrew Johnson | 1865 | |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Salmon P. Chase | 1861–1864 |

| William P. Fessenden | 1864–1865 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron | 1861–1862 |

| Edwin M. Stanton | 1862–1865 | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates | 1861–1864 |

| James Speed | 1864–1865 | |

| Postmaster General | Horatio King | 1861 |

| Montgomery Blair | 1861–1864 | |

| William Dennison | 1864–1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb B. Smith | 1861–1863 |

| John P. Usher | 1863–1865 | |

Supreme Court appointments

Lincoln appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Noah Haynes Swayne - 1862

- Samuel Freeman Miller - 1862

- David Davis - 1862

- Stephen Johnson Field - 1863

- Salmon P. Chase - Chief Justice - 1864

Assassination

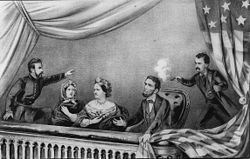

Lincoln met frequently with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as the war drew to a close. The two men planned matters of reconstruction, and it was evident to all that they held each other in high regard. During their last meeting, on April 14, 1865 (Good Friday), Lincoln invited Grant to a social engagement that evening. Grant declined (Grant's wife, Julia Dent Grant, is said to have strongly disliked Mary Todd Lincoln).

Without the General and his wife, or his bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon, to whom he related his famous dream of his own assassination, the Lincolns left to attend a play at Ford's Theater. The play was Our American Cousin, a musical comedy by the British writer Tom Taylor (1817-1880). As Lincoln sat in the balcony, John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and Southern sympathizer from Maryland, crept up behind Lincoln in his state box and aimed a single-shot, round-slug .44 caliber Deringer at the President's head, firing at point-blank range. He shouted "Sic semper tyrannis!" (Latin: "Thus always to tyrants," and Virginia's state motto; some accounts say he added "The South is avenged!") and jumped from the balcony to the stage below. Contrary to popular belief, Booth did not break his leg in the jump. He broke his leg several days later when his horse fell on him.

Booth and several other conspirators had planned to kill a number of other government officials at the same time, but for various reasons Lincoln's was the only assassination actually carried out (although Secretary of State William H. Seward was badly injured by an assailant). Booth managed to limp to his horse and escape, and the mortally wounded president was taken to a house across the street, now called the Petersen House, where he lay in a coma for some time before he quietly expired.

Abraham Lincoln was officially pronounced dead at 7:22 AM the next morning, April 15, 1865. Upon seeing him die, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton lamented, "Now he belongs to the angels." However, not long after he or others decided that 'ages' was more pleasing to the ear and appropriate to the occasion, so the quote itself was changed to Now he belongs to the ages.

Booth and several of his conspirators were eventually captured, and either hanged or imprisoned. Booth himself was shot when discovered holed up in a barn. Four people were tried by military tribunal and hanged for the assassination plot (David Herold, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell (aka Lewis Payne), and Mary Surratt, the first woman ever executed by the United States government.) Three people were sentenced to life imprisonment (Michael O'Laughlin, Samuel Arnold, and Samuel Mudd). Edward Spangler was sentenced to six years imprisonment. John Surratt, tried later by a civilian court, was acquitted. The fairness of the convictions, particularly of Mary Surratt, have been called into question, and there are doubts as to the exact degree of her involvement, if any, in the conspiracy.

Lincoln's body was carried by train in a grand funeral procession through several states on its way back to Illinois. The nation mourned a man whom many viewed as the savior of the United States, and protector and defender of what Lincoln himself called "the government of the people, by the people, and for the people." Critics say that in fact the Confederates were the ones defending the right to self-governance and Lincoln was suppressing that right. They further insist that Lincoln only preserved the Union in a geographical sense while destroying its voluntary nature.

Many medical experts now believe that Lincoln may have been dying before he was assassinated. He was showing signs late in his Presidency of congestive heart failure. Lincoln, who was 6 feet 4 inches tall (the tallest President) had large hands and long, lanky arms and legs. Many doctors believe that this was evidence that Lincoln also suffered from Marfan's Syndrome. Both diseases have been known to be fatal.

Lincoln family

President Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln had four sons.

- Robert Todd Lincoln : b. August 1, 1843 in Springfield, Illinois - d. July 26, 1926 in Manchester, Vermont.

- Edward Baker Lincoln : b. March 10, 1846 in Springfield, Illinois - d. February 1, 1850 in Springfield, Illinois

- William Wallace Lincoln : b. December 21, 1850 in Springfield, Illinois - d. February 20, 1862 in Washington, D.C.

- Thomas "Tad" Lincoln : b. April 4, 1853 in Springfield, Illinois - d. July 16, 1871 in Chicago, Illinois.

Only Robert survived into adulthood. Of Robert's children, only Jessie Lincoln had any children (2 - Mary Lincoln Beckwith and Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith). Neither Robert Beckwith nor Mary Beckwith had any children, so Abraham Lincoln's bloodline ended when Robert Beckwith (Lincoln's great-grandson) died on December 24, 1985. [3]

Lincoln's sexuality

Abraham Lincoln is known to have lived for four years with Joshua Speed, when both men were in their twenties. They shared a bed during these years and developed a friendship that would last until their deaths. A number of biographers, beginning with Carl Sandburg in 1926, have suggested or implied that this relationship was homosexual, though others have argued that Lincoln and Speed shared a bed purely because of their poor financial circumstances. When Speed left Lincoln and returned to Kentucky after their four years of cohabitation, Lincoln is believed to have suffered something approaching a nervous breakdown. He displayed remarkable intimacy and affection in his correspondence with Speed, more so even than in his correspondence with his wife.

Lincoln shared beds with several other men during his life. Amongst these was an army officer, David Derickson, assigned to Lincoln's bodyguard in 1862. Several sources characterise the relationship between the two as intimiate, and it was the subject of gossip in Washington at the time. They shared a bed during the absences of Lincoln's wife, until Derickson was promoted in 1863. Again, some biographers have interpreted this as a homosexual affair. A recent study has also pointed to homosexual themes in bawdy poetry written by the teenage Lincoln, especially a poem in which a boy marries another boy.

Lincoln exhumed

Lincoln was buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, where a 177-foot-tall granite tomb surmounted with several bronze statues of Lincoln was constructed by 1874. Lincoln's wife and three of his four sons are also buried there (Robert is buried in Arlington National Cemetery). In the years following his death, attempts were made to steal Lincoln's body and hold it for ransom. Around 1900, Robert Todd Lincoln decided that, in order to prevent body theft, it was necessary to build a permanent crypt for his father. Lincoln's coffin would be encased in concrete several feet thick, surrounded by a cage, and buried beneath a rock slab. On September 26, 1901, Lincoln's body was exhumed so that it could be reinterred in the newly built crypt. However, those present (there were 23 of them) feared that his body might have been stolen in the intervening years. They decided to open the coffin and check (picture). When they did, they were amazed at the sight. Lincoln's body was almost perfectly preserved. It had been embalmed so many times following his death that his body had not decayed. In fact, he was perfectly recognizable, even more than thirty years after his death. On his chest, they could see red, white, and blue specks — remnants of the American flag with which he was buried, which had by then disintegrated.

All 23 of the people who viewed the remains of Mr. Lincoln have long since passed away. One of the last, a youth of 13 at the time, was Fleetwood Lindley, who died on February 1, 1963. Three days before he died, Mr. Lindley was interviewed. He said, "Yes, his face was chalky white. His clothes were mildewed. And I was allowed to hold one of the leather straps as we lowered the casket for the concrete to be poured. I was not scared at the time but I slept with Lincoln for the next six months." (ALRS)

Another youth present, George Cashman, also remembered the event until his death and it made even more of an impression on him, even as an adult. The last years of his life, George Cashman was the curator of the National Landmark in Springfield called "Lincoln's Tomb." He particularly enjoyed relating his story to the more than one million visitors to the site each year. Mr. Cashman passed away in 1979, the last person to have viewed the remains of Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln memorialized

Lincoln has been memorialized in many city names, notably the capital of Nebraska; with the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC (illustrated, right); on the U.S. $5 bill and the 1 cent coin; and as part of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Lincoln's Tomb, Lincoln's Home in Springfield, New Salem, Illinois (a reconstruction of Lincoln's early adult hometown), Ford's Theater and Petersen House are all preserved as museums.

On February 12, 1892 Abraham Lincoln's birthday was declared to be a federal holiday in the United States, though it was later combined with Washington's birthday in the form of President's Day. (They are still celebrated separately in Illinois.)

The statue of Lincoln that is furthest south is outside the USA - in Mexico. A gift from the United States, dedicated in 1966 by LBJ, it is a 13 foot high bronze statue in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico. The USA received a statue of Benito Juárez in exchange, which is in Washington, DC. Juárez and Lincoln exchanged friendly letters, and Mexico remembers Lincoln's opposition to the Mexican War. There are also at least two statues of Lincoln in England, one in London and another in Manchester .

The ballistic missile submarine Abraham Lincoln (SSBN-602) and the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) were named in his honor.

There is a notion that clocks display the time 10:10 in advertisements, and in shops before they are sold, in memory of Lincoln's death. This is certainly not true since Lincoln was shot at 10:15 pm and died at 7:22 am. [4]

Quotes

"I should like to know, if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle, and making exceptions to it, where will it stop? If one man says it does not mean a negro, why may not another man say it does not mean another man? If the Declaration is not the truth, let us get the statute book in which we find it and tear it out. Who is so bold as to do it? If it is not true, let us tear it out." - From the Lincoln-Douglas debates (1858)

The Ten Cannots are often attributed to Lincoln; however, their true author is the Rev. William J. H. Boetcker, a religious leader and motivational speaker more than 60 years Lincoln's junior.

Views on Race

Although Lincoln is well known for his role in abolishing slavery in the United States, Canadian ethicist David Sztybel has collected many examples of racism in Lincoln's speeches and writings. For example:

"Negro equality! Fudge! How long, in the government of a God, great enough to make and maintain this Universe, shall there continue knaves to vend, and fools to gulp, so low a piece of demagougism [sic] as this." - (Abraham Lincoln, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, [New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953], v. 3, p. 399. Fragments: Notes for Speeches, Sept. 6, 1859)

"I will say, then, that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races--that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which will ever forbid the two races living together in terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together, there must be the position of superior and inferior. I am as much as any other man in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race." - op cit pp. 247-8. (Sixth Debate with Steven A. Douglas at Quincy, Ill., Oct. 13, 1858)

Nevertheless, despite early hesitation due to campaign promises and the need to keep the slaveowning border states from joining the Confederacy, Lincoln did more than any of his predecessors to ensure the eventual destruction of slavery. He spoke about the evils of slavery throughout his career, strongly backed the Thirteenth Amendment, and as president consulted with black leaders such as Frederick Douglass. In issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln made the ending of slavery a key Union war aim.

Related articles

- U.S. presidential election, 1860

- U.S. presidential election, 1864

- Lincoln's second inaugural address

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Lincoln-Kennedy coincidences

- Movies: D.W. Griffith's 'Abraham Lincoln', The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln

Further reading

- Lincoln by David Herbert Donald. ISBN 068482535X

- Lincoln Reconsidered: Essays on the Civil War Era by David Herbert Donald. ISBN 0375725326

- Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President by Allen C. Guelzo. ISBN 0802842933

External links

- Abraham Lincoln Research Site

- First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln

- Second Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln

- Abraham Lincoln - Encarta

- Abraham Lincoln Online

- The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

- Especially for Students: An Overview of Abraham Lincoln's Life

- Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College

- Original 1860's Harper's Weekly Images and News on Abraham Lincoln

- The Lincoln Log: A Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln

- The Lincoln Museum

- John Summerfield Staples, President Lincoln's "Substitute"

- First State of the Union Address of Abraham Lincoln

- Second State of the Union Address of Abraham Lincoln

- Third State of the Union Address of Abraham Lincoln

- Fourth State of the Union Address of Abraham Lincoln

- Documents at Project Gutenberg

- Volume 1 and Volume 2 of Abraham Lincoln: a History (1890) by John Hay (1835-1905) & John George Nicolay (1832-1901)

- eText of The Boys' Life of Abraham Lincoln (1907) by Nicolay, Helen (1866-1954)