Homeopathy

Homeopathy (from the Greek hómoios- ὅμοιος- ("like-") + páthos πάθος ("suffering"))[1] is a form of alternative medicine first expounded by Samuel Hahnemann in 1796, that treats a disease with heavily diluted preparations created from substances that would ordinarily cause effects similar to the disease's symptoms. These substances are serially diluted, with shaking ("succussing") between each step, under the belief that this increases the effect of the treatment. This dilution is usually quite extensive, and often continues until no molecules of the original substance are likely to remain.[2]

As well as the disease symptoms, homeopaths may use aspects of the patient's physical and psychological state to select between treatments.[3][4] Reference books, known as repertories, which have been created by homeopaths, are then consulted, and a remedy selected based on the index of symptoms. Homeopathic remedies are generally considered safe, with rare exceptions.[5][6] However, homeopaths have been criticized for putting patients at risk with advice to avoid conventional medicine, such as vaccinations,[7] anti-malarial drugs,[8] and antibiotics.[9] In many countries, the laws that govern the regulation and testing of conventional drugs do not apply to homeopathic remedies.[10]

Claims of homeopathy's efficacy (beyond the placebo effect) are unsupported by the collective weight of scientific and clinical evidence.[11][12][13][14][15] Specific pharmacological effect with no active molecules is scientifically implausible[16][17] and violates fundamental principles of science,[18] including the law of mass action.[18] Supporters claim a few high-quality studies support the efficacy of homeopathy; however, the studies they point to are not definitive and have not been replicated,[19] several high-quality studies exist showing no evidence for any effect from homeopathy, and studies of homeopathic remedies have generally been shown to have problems that prevent them from being considered unambiguous evidence for homeopathy's efficacy.[20][11][13][21][14] The lack of convincing scientific evidence supporting homeopathy's efficacy[15] and its use of remedies lacking active ingredients have caused homeopathy to be described as pseudoscience[22] and quackery.[23][24]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

History

18th-century medicine

At the time of the inception of homeopathy, the late 18th century, mainstream medicine employed such measures as bloodletting and purging, the use of laxatives and enemas, and the administration of complex mixtures, such as Venice treacle, which was made from 64 substances including opium, myrrh, and viper's flesh.[25][26] Such measures often worsened symptoms and sometimes proved fatal.[27][28] While the virtues of these treatments had been extolled for centuries,[29] Hahnemann rejected such methods as irrational and unadvisable.[30] Instead, he favored the use of single drugs at lower doses and promoted an immaterial, vitalistic view of how living organisms function, believing that diseases have spiritual, as well as physical causes.[31][32] (At the time, vitalism was part of mainstream science; in the twentieth century, however, medicine discarded vitalism, with the development of microbiology, the germ theory of disease,[33] and advances in chemistry.[34][35]) Hahnemann also advocated various lifestyle improvements to his patients, including exercise, diet, and cleanliness.[30][36]

Hahnemann's concept

Samuel Hahnemann conceived of homeopathy while translating a medical treatise by Scottish physician and chemist William Cullen into German.[37] Being sceptical of Cullen’s theory concerning cinchona’s action in malaria, Hahnemann ingested some of the bark specifically to see if it cured fever "by virtue of its effect of strengthening the stomach".[38] Upon ingesting the bark, he noticed few stomach symptoms, but did experience fever, shivering and joint pain, symptoms similar to some of the early symptoms of malaria, the disease that the bark was ordinarily used to treat. From this, Hahnemann came to believe that all effective drugs produce symptoms in healthy individuals similar to those of the diseases that they can treat. This later became known as the "law of similars", the most important concept of homeopathy.[37] The term "homeopathy" was coined by Hahnemann and first appeared in print in 1807, although he began outlining his theories of "medical similars" in a series of articles and monographs in 1796.[39]

Hahnemann began to test what effects substances produced in humans, a procedure which would later become known as "homeopathic proving".[40] These time-consuming tests required subjects to clearly record all of their symptoms as well as the ancillary conditions under which they appeared. Hahnemann saw these data as a way of identifying substances suitable for the treatment of particular diseases.[40] The first collection of provings was published in 1805 and a second collection of 65 remedies appeared in his book, Materia Medica Pura, in 1810.[41] Hahnemann believed that large doses of drugs that caused similar symptoms would only aggravate illness, and so he advocated extreme dilutions of the substances; he devised a technique for making dilutions that he believed would preserve a substance's therapeutic properties while removing its harmful effects,[2] proposing that this process aroused and enhanced "spirit-like medicinal powers held within a drug".[42] He gathered and published a complete overview of his new medical system in his 1810 book, The Organon of the Healing Art, whose 6th edition, published in 1921, is still used by homeopaths today.[37]

Rise to popularity and early criticism

During the 19th century homeopathy grew in popularity. In 1830, the first homeopathic schools opened, and throughout the 19th century dozens of homeopathic institutions appeared in Europe and the United States.[43] By 1900, there were 22 homeopathic colleges and 15,000 practitioners in the United States.[19] Because of then-current medicine's reliance on unscientific blood-letting and other untested, often dangerous treatments, patients of homeopaths often had better outcomes than those of the doctors of the time.[44] Homeopathic remedies, even if ineffective, would almost surely cause no harm, making the users of homeopathic remedies less likely to be killed by the treatment that was supposed to be helping them.[37] The relative success of homeopathy in the 19th century may have led to the abandonment of the ineffective and harmful treatments of bloodletting and purging and to have begun the move towards more effective, science based medicine.[28]

In the early 19th century, homeopathy began to be criticised. Sir John Forbes, physician to Queen Victoria, said the extremely small doses of homeopathy were regularly derided as useless, laughably ridiculous and "an outrage to human reason".[45] James Young Simpson said of the highly diluted drugs: "No poison, however strong or powerful, the billionth or decillionth of which would in the least degree affect a man or harm a fly."[46] Nineteenth century American physician and author Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. was also a vocal critic of homeopathy and published an essay in 1842 entitled Homœopathy, and its kindred delusions.[47] The members of the French Homeopathic Society observed in 1867 that some of the leading homeopathists of Europe were not only abandoning the practice of administering infinitesimal doses, but were also no longer defending it.[48] The last school in the U.S. exclusively teaching homeopathy closed in 1920.[37]

Revival in the late 20th Century

The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (sponsored by New York Senator, and Homeopathic Physician Royal Copeland) of 1938 recognized homeopathic remedies as drugs. By the 1950s there were only 75 pure homeopaths practicing in the USA.[49] However, in the mid to late 1970s, homeopathy made a significant comeback and sales of some homeopathic companies increased tenfold.[50] Homeopathy was also revived worldwide;[51] for example, Brazil in the 1970s and Germany in the 1980s.[52] The medical profession started to integrate such ideas in the 1990s[53] and big mainstream pharmacies started competing for this business.[54]

General philosophy

Homeopathy is a vitalist philosophy in that it regards diseases and sickness to be caused by disturbances in a hypothetical vital force or life force in humans and that these disturbances manifest themselves as unique symptoms. Homeopathy maintains that the vital force has the ability to react and adapt to internal and external causes, which homeopaths refer to as the "law of susceptibility". The law of susceptibility states that a negative state of mind can attract hypothetical disease entities called "miasms" to invade the body and produce symptoms of diseases.[37] However, Hahnemann rejected the notion of a disease as a separate thing or invading entity[55] and insisted that it was always part of the "living whole".[56]

Law of similars

Hahnemann observed from his experiments with cinchona bark, used as a treatment for malaria, that the effects he experienced from ingesting the bark were similar to the symptoms of malaria. He therefore reasoned that cure proceeds through similarity, and that treatments must be able to produce symptoms in healthy individuals similar to those of the disease being treated. Through further experiments with other substances, Hahnemann conceived of the "law of similars", otherwise known as "like cures like" (Latin: similia similibus curentur) as a fundamental healing principle. He believed that by inducing a disease through use of drugs, the artificial symptoms empowered the vital force to neutralise and expel the original disease and that this artificial disturbance would naturally subside when the dosing ceased.[37]

Miasms and disease

Hahnemann found as early as 1816 that the patients he treated through homeopathy still suffered from chronic diseases that he was unable to cure.[57] In 1828,[58] he introduced the concept of miasms, which he regarded as underlying causes for many known diseases. A miasm is often defined by homeopaths as an imputed "peculiar morbid derangement of our vital force".[59] Hahnemann associated each miasm with specific diseases, with each miasm seen as the root cause of several diseases. According to Hahnemann, initial exposure to miasms causes local symptoms, such as skin or venereal diseases, but if these symptoms are suppressed by medication, the cause goes deeper and begins to manifest itself as diseases of the internal organs.[60] Homeopathy maintains that treating diseases by directly opposing their symptoms, as is sometimes done in conventional medicine, is not so effective because all "disease can generally be traced to some latent, deep-seated, underlying chronic, or inherited tendency".[61] The underlying imputed miasm still remains, and deep-seated ailments can only be corrected by removing the deeper disturbance of the vital force.[62]

Hahnemann's miasm theory remains disputed and controversial within homeopathy even in modern times. In 1978, Anthony Campbell, then a consultant physician at The Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, criticised statements by George Vithoulkas claiming that syphilis, when treated with antibiotics, would develop into secondary and tertiary syphilis with involvement of the central nervous system. This conflicts with scientific studies, which indicate that penicillin treatment produces a complete cure of syphilis in more than 90% of cases.[63] Campbell described this as "a thoroughly irresponsible statement which could mislead an unfortunate layman into refusing orthodox treatment".[9]

Originally Hahnemann presented only three miasms, of which the most important was "psora" (Greek for itch), described as being related to any itching diseases of the skin, supposed to be derived from suppressed scabies, and claimed to be the foundation of many further disease conditions. Hahnemann claimed psora to be the cause of such diseases as epilepsy, cancer, jaundice, deafness, and cataracts.[32] Since Hahnemann's time, other miasms have been proposed, some replacing one or more of psora's proposed functions, including tubercular miasms and cancer miasms.[60]

Preparation of remedies

Dilution and succussion

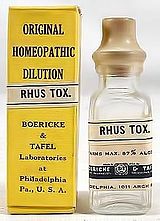

In producing treatments for diseases, homeopaths use a process called "dynamisation" or "potentisation" whereby the remedy is diluted with alcohol or distilled water and then vigorously shaken by ten hard strikes against an elastic body in a process called "succussion". Hahnemann thought that the use of remedies which present symptoms similar to those of disease in healthy individuals would only intensify the symptoms and exacerbate the condition, so he advocated the dilution of the remedies. During the process of potentisation, homeopaths believe that the vital energy of the diluted substance is activated and its energy released by vigorous shaking of the substance. For this purpose, Hahnemann had a saddle maker construct a special wooden striking board covered in leather on one side and stuffed with horsehair.[64][65] Insoluble solids, such as quartz and oyster shell, are diluted by grinding them with lactose (trituration).

Three potency scales are in regular use in homeopathy. Hahnemann created the centesimal or "C scale", diluting a substance by a factor of 100 at each stage. The centesimal scale was favored by Hahnemann for most of his life. A 2C dilution requires a substance to be diluted to one part in one hundred, and then some of that diluted solution is diluted by a further factor of one hundred. This works out to one part of the original solution mixed into 9,999 parts (100 × 100 −1) of the diluent.[66] A 6C dilution repeats this process six times, ending up with the original material diluted by a factor of 100-6=10-12. Higher dilutions follow the same pattern. In homeopathy, a solution that is more dilute is described as having a higher potency, and more dilute substances are considered by homeopaths to be stronger and deeper-acting remedies.[67] The end product is often so diluted that it is indistinguishable from the dilutant (pure water, sugar or alcohol).[2][68][69]

| X Scale | C Scale | Ratio | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1X | — | 1:10 | described as low potency |

| 2X | 1C | 1:100 | called higher potency than 1X by homeopaths |

| 6X | 3C | 10-6 | |

| 8X | 4C | 10-8 | allowable concentration of arsenic in US drinking water[70] |

| 12X | 6C | 10-12 | |

| 24X | 12C | 10-24 | Has a 60% probability of containing one molecule of original material if one mole of the original substance was used. |

| 60X | 30C | 10-60 | Dilution advocated by Hahnemann for most purposes: this would require giving two billion doses per second to six billion people for 4 billion years to deliver a single molecule of the original material to any patient. |

| 400X | 200C | 10-400 | Dilution of popular homeopathic flu remedy Oscillococcinum |

| Note: the "X scale" is also called "D scale". 1X = 1D, 2X = 2D, etc. | |||

Hahnemann advocated 30C dilutions for most purposes (that is, dilution by a factor of 1060).[71] A popular homeopathic treatment for the flu is a 200C dilution of duck liver, marketed under the name Oscillococcinum.

Commonly, critics of homeopathy, as well as homeopaths themselves, attempt to illustrate the dilutions involved in homeopathy with examples.[72] Hahnemann is reported to have joked that a suitable procedure to deal with an epidemic would be to empty a bottle of poison into Lake Geneva, if it could be succussed 60 times.[73][74][75] Another example given by a critic of homeopathy states that a 12C solution is equivalent to a "pinch of salt in both the North and South Atlantic Oceans",[73][74] which is approximately correct.[76] One third of a drop of some original substance diluted into all the water on earth would produce a remedy with a concentration of about 13C.[77][78][72]

Some homeopaths developed a decimal scale (D or X), diluting the substance to ten times its original volume each stage. The D or X scale dilution is therefore half that of the same value of the C scale; for example, "12X" is the same level of dilution as "6C". Hahnemann never used this scale but it was very popular throughout the 19th century and still is in Europe. This potency scale appears to have been introduced in the 1830s by the American homeopath, Constantine Hering.[79] In the last ten years of his life, Hahnemann also developed a quintamillesimal (Q) or LM scale diluting the drug 1 part in 50,000 parts of diluent.[80] A given dilution on the Q scale is roughly 2.35 times its designation on the C scale. For example a remedy described as "20Q" has about the same concentration as a "47C" remedy.[81]

Not all homeopaths advocate extremely high dilutions. Many of the early homeopaths were originally doctors and generally tended to use lower dilutions such as "3X" or "6X", rarely going beyond "12X". The split between lower and higher dilutions followed ideological lines with the former stressing pathology and a strong link to conventional medicine, while the latter emphasised vital force, miasms and a spiritual interpretation of disease.[82][83] Some products with such relatively lower dilutions continue to be sold, but, without evidence to the contrary, these levels of dilution are still considered to be so small as to put any effect from such treatments down to placebo.[84] [85]

Coverage in the mainstream press

The BBC's Horizon and ABC's 20/20 broadcast programs described scientific testing of homeopathic dilutions that were unable to differentiate these dilutions from water.[65][86]

Provings

In order to determine which specific remedies could be used to treat which diseases, Hahnemann experimented on himself and others for several years, before using remedies on patients. His experiments did not initially consist of giving remedies to the sick, because he thought that the most similar remedy, by virtue of its ability to induce symptoms similar to the disease itself, would make it impossible to determine which symptoms came from the remedy and which from the disease itself. Therefore, sick people were excluded from these experiments. The method used for determining which remedies were suitable for specific diseases was called "proving", after the original German word "Prüfung", meaning "test". A homeopathic proving is the method by which the profile of a homeopathic remedy is determined.[87]

At first Hahnemann used molecular doses for provings, but he later advocated proving with remedies at a 30C dilution,[71] and most modern provings are carried out using ultradilute remedies in which it is highly unlikely that any of the original molecules remain.[88] During the process of proving, Hahnemann used healthy volunteers who were given remedies, and the resulting symptoms were compiled by observers into a "Drug Picture". During the process the volunteers were observed for months at a time and were made to keep extensive journals detailing all of their symptoms at specific times during the day. During the tests volunteers were forbidden from consuming coffee, tea, spices, or wine. They were also not allowed to play chess, because Hahnemann considered it to be "too exciting", though they were allowed to drink beer and were encouraged to moderately exercise. After the experiments were over, Hahnemann made the volunteers offer their hands and take an oath swearing that what they reported in their journals was the truth, at which time he would interrogate them extensively concerning their symptoms.

Provings have been described as important in the development of the clinical trial, due to their early use of simple control groups, systematic and quantitative procedures, and some of the first application of statistics in medicine.[89] The lengthy records of self-experimentation by homeopaths have occasionally proven useful in the development of modern drugs: For example, evidence nitroglycerin might be useful as a treatment for angina was discovered by looking through homeopathic provings, though homeopaths themselves never used it for that purpose at that time.[90] The first recorded provings were published by Hahnemann in his 1796 Essay on a new principle. His Fragmenta de viribus (1805)[citation needed] contained the results of 27 provings, and his 1810 Materia Medica Pura contained 65.[91] For James Tyler Kent's 1905 Lectures on Homoeopathic Materia Medica, 217 remedies underwent provings and newer substances are continually added to contemporary versions.

Repertory

A compilation of reports of many homeopathic provings is known as a homeopathic materia medica. In practice the usefulness of such a compilation is limited because a practitioner does not need to look up the symptoms for a particular remedy, but rather to explore the remedies for a particular symptom. This need is filled by the homeopathic repertory, which is an index of symptoms, listing after each symptom those remedies that are associated with it. Repertories are often very extensive and may include data from clinical experience in addition to provings. There is often lively debate among the compilers of a repertory and interested practitioners over the veracity of a particular inclusion. The first symptomatic index of the homeopathic materia medica was arranged by Hahnemann. Soon after, one of his students Clemens von Bönninghausen, created the Therapeutic pocket book, another homeopathic repertory.[92] The first such Homeopathic Repertory was Dr. George Jahr's Repertory, published in 1835 in German and then again in 1838 in English and edited by Dr. Constantine Hering. This version was less focused on disease categories and would be the forerunner to Kent's later works.[93] It consisted of three large volumes. Such repertories increased in size and detail as time progressed.

Treatments

Homeopaths generally begin with detailed examinations of their patients' histories, including questions regarding their physical, mental and emotional states, their life circumstances and any physical/emotional illnesses. The homeopath then attempts to translate this information into a complex formula of mental and physical symptoms, including likes, dislikes, innate predispositions and even body type.[94] The goal is to develop a comprehensive representation of each individual's overall health. This information can then be compared with similar lists in the drug provings found in the homeopathic materia medica. Assisted by further dialogues with the patient, the homeopath then aims to find the one drug most closely matching the "symptom totality" of the patient. There are many methods for determining the most-similar remedy (the simillimum), and homeopaths sometimes disagree. This is partly due to the insurmountable complexity of the "totality of symptoms" concept. That is, homeopaths do not include all symptoms when determining which medicine is most appropriate, but decide for themselves which are the most characteristic. This subjective evaluation of case analysis relies on the knowledge and experience of the homeopath doing the diagnosis.

Some diversity in approaches to treatments exists among homeopaths. "Classical" homeopathy generally involves detailed examinations of a patient's history and infrequent doses of a single remedy as the patient is monitored for improvements in symptoms, while "clinical" homeopathy involves combinations of remedies to address the various symptoms of an illness.[95]

Remedies

"Remedy" is a technical term used in homeopathy to refer to a substance prepared with a particular procedure and intended for treating patients. Homeopathic practitioners rely on two types of reference when prescribing remedies: Materia medicae and repertories. A homeopathic Materia medica is a collection of "drug pictures", organised alphabetically by remedy, that describes the symptom patterns associated with individual remedies. A homeopathic repertory is an index of disease symptoms that lists remedies associated with specific symptoms.[96]

Homeopathy uses many animal, plant, mineral, and synthetic substances in its remedies. Examples include Arsenicum album (arsenic oxide), Natrum muriaticum (sodium chloride or table salt), Lachesis muta (the venom of the bushmaster snake), Opium, and Thyroidinum (thyroid hormone). Homeopaths also use treatments called nosodes (from the Greek nosos, disease) made from diseased or pathological products such as fecal, urinary, and respiratory discharges, blood, and tissue.[97] Homeopathic remedies prepared from healthy specimens are called Sarcodes.

Some modern homeopaths have considered more esoteric substances, known as "imponderables" because they do not originate from a material but from electromagnetic energy presumed to have been "captured" by alcohol or lactose. Examples include X-rays, sunlight,[98] and electricity.[99] Recent ventures by homeopaths into even more esoteric substances include thunderstorms (prepared from collected rainwater).[100] Today there are about 3,000 different remedies commonly used in homeopathy.[101] Some homeopaths also use techniques that are regarded by other practitioners as controversial. These include paper remedies, where the substance and dilution are written on a piece of paper and either pinned to the patient's clothing, put in their pocket, or placed under a glass of water that is then given to the patient, as well as the use of radionics to prepare remedies. Such practices have been strongly criticised by classical homeopaths as unfounded, speculative and verging upon magic and superstition.[102][103]

Isopathy

Isopathy is a therapy derived from homeopathy and was invented by Johann Joseph Wilhelm Lux in the 1830s.[93] Isopathy differs from homeopathy in general in that the remedies are made up either from things that cause the disease, or from products of the disease, such as pus. Many so-called "homeopathic vaccines" are a form of isopathy.[104]

Flower remedies

Flower remedies can be produced by placing flowers in water and exposing them to sunlight. The most famous of these are the Bach flower remedies, which were developed by the homeopath Edward Bach. The relationship between these remedies and homeopathy is controversial. On the one hand, the proponents of these remedies share homeopathy's vitalist world-view and the remedies are claimed to act through the same hypothetical "vital force". However, although many of the same plants are used as in homeopathy, the method of preparation is somewhat different, with Bach flower therapies supposedly being prepared in "gentler" ways, such as placing flowers in bowls of sunlit water, and so on.[105] There is no convincing scientific or clinical evidence for flower remedies being effective.[106]

Veterinary use

The idea of using homeopathy as a treatment for other animals, termed veterinary homeopathy, dates back to the inception of homeopathy; Hahnemann himself wrote and spoke of the use of homeopathy in animals other than humans.[107] In the United States, veterinary homeopathy is used by veterinarian members of the Academy for Veterinary Homeopathy and/or the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association.[108] The FDA has not approved homeopathic products as veterinary medicine in the US. In the UK, veterinary surgeons who use homeopathy belong to the Faculty of Homeopathy and/or to the British Association of Homeopathic Veterinary Surgeons. Animals may only be treated by qualified veterinary surgeons in the UK and some other countries. Internationally, the body that supports and represents homeopathic veterinarians is the International Association for Veterinary Homeopathy. The use of homeopathy in veterinary medicine is controversial, as there has been little scientific investigation and current research in the field is not of a high enough standard to provide reliable data.[109] Other studies have also found that giving animals placebos can play active roles in influencing pet owners to believe in the effectiveness of the treatment when none exists.[109]

Medical and scientific analysis

| Claims | Proponents claim that illnesses can be treated with specially prepared extreme dilutions of a substance that produces symptoms similar to the illness. Homeopathic remedies rarely contain any atom or molecule of the substance in the remedy. |

|---|---|

| Related scientific disciplines | Chemistry, Medicine |

| Year proposed | 1807 |

| Original proponents | Samuel Hahnemann |

| Subsequent proponents | Organizations: Boiron, Heel, Miralus Healthcare, Nelsons Individuals: Paul Herscu, Roger Morrison, Robin Murphy, Rajan Sankaran, Luc De Schepper, Jan Scholten, Jeremy Sherr, George Vithoulkas |

| (Overview of pseudoscientific concepts) | |

Homeopathy is unsupported by modern scientific research. The extreme dilutions used in homeopathic preparations usually leave none of the original material in the final product.[110][111] Pharmacological effect without active ingredients is inconsistent with the observed dose-response relationships of conventional drugs,[112] leaving only non-specific placebo effects[113][114][12] or various novel explanations. The proposed rationale for these extreme dilutions – that the water contains the "memory" or "vibration" from the diluted ingredient – is counter to the laws of chemistry and physics.[110] The lack of convincing scientific evidence supporting its efficacy[15] and its use of remedies without active ingredients have led to characterizations as pseudoscience and quackery.[22][23][24][115][116] Use of homeopathy may delay or replace medical treatment.[citation needed]

High dilutions

The extremely high dilutions in homeopathy have been a main point of criticism. Homeopaths believe that the methodical dilution of a substance, beginning with a 10% or lower solution and working downwards, with shaking after each dilution, produces a therapeutically active "remedy", in contrast to therapeutically inert water. However, homeopathic remedies are usually diluted to the point where there are no molecules from the original solution left in a dose of the final remedy.[111] Since even the longest-lived noncovalent structures in liquid water at room temperature are only stable for a few picoseconds,[117] critics have concluded that any effect that might have been present from the original substance can no longer exist.[118] Furthermore, since water will have been in contact with millions of different substances throughout its history, critics point out that any glass of water is therefore an extreme dilution of almost any conceivable substance, and so by drinking water one would, according to homeopathic principles, receive treatment for every imaginable condition.[119]

Practitioners of homeopathy contend that higher dilutions (fewer potential molecules in each dose) result in stronger medicinal effects. This idea is inconsistent with the observed dose-response relationships of conventional drugs, where the effects are dependent on the concentration of the active ingredient in the body.[112] This dose-response relationship has been confirmed in multitudinous experiments on organisms as diverse as nematodes,[120] rats,[121] and humans.[122]

Physicist Robert L. Park, former executive director of the American Physical Society, has noted that

since the least amount of a substance in a solution is one molecule, a 30C solution would have to have at least one molecule of the original substance dissolved in a minimum of 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 molecules of water. This would require a container more than 30,000,000,000 times the size of the Earth.[123]

Park has also noted that "to expect to get even one molecule of the 'medicinal' substance allegedly present in 30X pills, it would be necessary to take some two billion of them, which would total about a thousand tons of lactose plus whatever impurities the lactose contained". The laws of chemistry state that there is a limit to the dilution that can be made without losing the original substance altogether.[17] This limit, which is related to Avogadro's number, is roughly equal to homeopathic potencies of 12C or 24X (1 part in 1024).[113][124][72]

Research on medical effectiveness

The effectiveness of homeopathy has been in dispute since its inception. The methodological quality of the research base is generally low, with such problems as weaknesses in design or reporting, small sample size, and selection bias. No individual preparation has been unambiguously demonstrated to be different from a placebo.[11][125]

Positive results have been reported, but no single model has been sufficiently widely replicated. Local models proposed are far from convincing, and the nonlocal models proposed, often invoking "weak quantum theory",[126] would predict that it is impossible to nail down homeopathic effects with direct experimental testing.[127] For example, while some reports presented data that suggested homeopathic treatment of allergy was more effective than placebo,[128][129] subsequent studies have questioned the conclusions.[130][131] One of the earliest double blind studies concerning homeopathy was sponsored by the British government during World War II in which volunteers tested the effectiveness of homeopathic remedies against diluted mustard gas burns.[132]

Meta-analyses, in which large groups of studies are analysed and conclusions drawn based on the results as a whole, have been used to evaluate the effectiveness of homeopathy. Early meta-analyses investigating homeopathic remedies showed slightly positive results among the studies examined, but such studies have warned that it was impossible to draw firm conclusions due to low methodological quality and difficulty in controlling for publication bias in the studies reviewed.[133][21][134] One of the positive meta-analyses, by Linde, et al,[134] was later corrected by the authors, who wrote:

The evidence of bias [in homeopathic trials] weakens the findings of our original meta-analysis. Since we completed our literature search in 1995, a considerable number of new homeopathy trials have been published. The fact that a number of the new high-quality trials... have negative results, and a recent update of our review for the most “original” subtype of homeopathy (classical or individualized homeopathy), seem to confirm the finding that more rigorous trials have less-promising results. It seems, therefore, likely that our meta-analysis at least overestimated the effects of homeopathic treatments.[20][16]

In 2001, a meta-analysis of clinical trials on the effectiveness of homeopathy concluded that earlier clinical trials showed signs of major weakness in methodology and reporting, and that homeopathy trials were less randomized and reported less on dropouts than other types of trials.[21]

In 2005, a systematic review of publications suggested that mainstream journals had a publication bias against clinical trials showing positive results, and vice versa on the complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) journals, although it's probably an involuntary bias. A possible submission bias was also suggested, in which positive trials tend to be sent to CAM journals and negatives ones to mainstream journals.[135] It also noted that the reviews on all journals approached the matter on an impartial manner, although most of the reviews on CAM journals avoided noting the lack of plausibility, unlike the ones on mainstream journals who almost always mentioned it.[135]

In 2005, The Lancet medical journal published a meta-analysis of 110 placebo-controlled homeopathy trials and 110 matched medical trials based upon the Swiss government's Program for Evaluating Complementary Medicine, or PEK. The study concluded that its findings were compatible with the notion that the clinical effects of homeopathy are nothing more than placebo effects.[16]

A 2006 meta-analysis of six trials evaluating homeopathic treatments to reduce cancer therapy side effects following radiotherapy and chemotherapy found "encouraging but not convincing" evidence in support of homeopathic treatment. Their analysis concluded that there was "insufficient evidence to support clinical efficacy of homeopathic therapy in cancer care".[136]

A 2007 systematic review of homeopathy for children and adolescents found that the evidence for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and childhood diarrhea was mixed. No difference from placebo was found for adenoid vegetation, asthma, or upper respiratory tract infection. Evidence was not sufficient to recommend any therapeutic or preventative intervention.[14]

The Cochrane Library found insufficient clinical evidence to evaluate the efficacy of homeopathic treatments for asthma[137] or dementia,[138] or for the use of homeopathy in induction of labor.[139] Other researchers found no evidence that homeopathy is beneficial for osteoarthritis,[140] migraines[141] or delayed-onset muscle soreness.[95]

Health organisations such as UK's National Health Service,[142] the American Medical Association,[13] and the FASEB[118] have issued statements of their conclusion that there is no convincing scientific evidence to support the use of homeopathic treatments in medicine.

Clinical studies of the medical efficacy of homeopathy have been criticised by some homeopaths as being irrelevant because they do not test "classical homeopathy".[143][144] There have, however, been a number of clinical trials that have tested individualized homeopathy. A 1998 review[145] found 32 trials that met their inclusion criteria, 19 of which were placebo-controlled and provided enough data for meta-analysis. These 19 studies showed a pooled odds ratio of 1.17 to 2.23 in favor of individualized homeopathy over the placebo, but no difference was seen when the analysis was restricted to the methodologically best trials. The authors concluded "that the results of the available randomized trials suggest that individualized homeopathy has an effect over placebo. The evidence, however, is not convincing because of methodological shortcomings and inconsistencies."

Jack Killen, acting deputy director of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, says homeopathy "goes beyond current understanding of chemistry and physics." He adds: "There is, to my knowledge, no condition for which homeopathy has been proven to be an effective treatment."[15]

Research on effects in other biological systems

While some articles have suggested that homeopathic solutions of high dilution can have statistically significant effects on organic processes including the growth of grain,[146] histamine release by leukocytes,[147] and enzyme reactions, such evidence is disputed since attempts to replicate them have failed.[148][149][150][151][152]

In 1987, French immunologist Jacques Benveniste submitted a paper to the journal Nature while working at INSERM. The paper purported to have discovered that basophils released histamine when exposed to a homeopathic dilution of anti-immunoglobulin E, a type of white blood cell. The journal editors, sceptical of the results, requested that the study be replicated in a separate laboratory. Upon replication in four separate laboratories the study was published. Still sceptical of the findings, Nature assembled an independent investigative team to determine the accuracy of the research, consisting of Nature editor and physicist Sir John Maddox, American scientific fraud investigator and chemist Walter Stewart, and sceptic and magician James Randi. After investigating the findings and methodology of the experiment, the team found that the experiments were "statistically ill-controlled", "interpretation has been clouded by the exclusion of measurements in conflict with the claim", and concluded, "We believe that experimental data have been uncritically assessed and their imperfections inadequately reported."[153][154][155] James Randi stated that he doubted that there had been any conscious fraud, but that the researchers had allowed "wishful thinking" to influence their interpretation of the data.[154]

Ethical and safety issues

As homeopathic remedies usually contain only water and/or alcohol, they are thought to be generally safe. Only in rare cases are the original ingredients present at detectable levels. This may be due to improper preparation or intentional low dilution. Instances of arsenic poisoning have occurred after use of arsenic-containing homeopathic preparations.[6] Zicam Nasal Spray, which contains 2X (1:100) zinc gluconate, reportedly caused a small percentage of users to lose their sense of smell;[156] 340 cases were settled out of court in 2006 for 12 million U.S. dollars.[5][157]

Critics of homeopathy have cited other concerns over homeopathic remedies, most seriously, cases of patients of homeopathy failing to receive proper treatment for diseases that it is claimed could have been diagnosed or cured with conventional medicine. Several surveys demonstrate that some (particularly non-physician) homeopaths advise their patients against immunisation.[158][7][159] Some homeopaths suggest that vaccines be replaced with homeopathically diluted "nosodes", created from dilutions of biological agents – including material such as vomit, feces or infected human tissues. While Hahnemann was opposed to such preparations, modern homeopaths often use them although there is no evidence to indicate they have any beneficial effects.[160][161] Cases of homeopaths advising against the use of anti-malarial drugs have been identified.[162][163][8] This puts visitors to the tropics who take this advice in severe danger, since homeopathic remedies are completely ineffective against the malaria parasite.[162][163][8] Also, in one case in 2004, a homeopath instructed one of her patients to stop taking conventional medication for a heart condition, advising her on 22 June 2004 to "Stop ALL medications including homeopathic", advising her on or around 20 August that she no longer needed to take her heart medication, and adding on 23 August, "She just cannot take ANY drugs – I have suggested some homeopathic remedies ... I feel confident that if she follows the advice she will regain her health." The patient was admitted to hospital the next day, and died eight days later, the final diagnosis being "acute heart failure due to treatment discontinuation".[164][165]

In 1978, Anthony Campbell, then a consultant physician at The Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, criticised statements made by George Vithoulkas to promote his homeopathic treatments. Vithoulkas stated that syphilis, when treated with antibiotics, would develop into secondary and tertiary syphilis with involvement of the central nervous system. Campbell described this as a thoroughly irresponsible statement which could mislead an unfortunate layman into refusing conventional medical treatment.[9] This claim echoes the idea that treating a disease with external medication used to treat the symptoms would only drive it deeper into the body and conflicts with scientific studies, which indicate that penicillin treatment produces a complete cure of syphilis in more than 90% of cases.[63]

A 2006 review by W. Steven Pray of the College of Pharmacy at Southwestern Oklahoma State University recommends that pharmacy colleges include a required course in unproven medications and therapies, that ethical dilemmas inherent in recommending products lacking proven safety and efficacy data be discussed, and that students should be taught where unproven systems such as homeopathy depart from evidence-based medicine.[166]

Edzard Ernst, the first Professor of Complementary Medicine in the United Kingdom, has expressed his concerns about pharmacists who violate their ethical code by failing to provide customers with "necessary and relevant information" about the true nature of the homeopathic products they advertise and sell:

- "My plea is simply for honesty. Let people buy what they want, but tell them the truth about what they are buying. These treatments are biologically implausible and the clinical tests have shown they don't do anything at all in human beings. The argument that this information is not relevant or important for customers is quite simply ridiculous."[167]

Regulation and prevalence

Homeopathy is fairly common in some countries while being uncommon in others; is highly regulated in some countries and mostly unregulated in others. Regulations vary in Europe depending on the country. In some countries, there are no specific legal regulations concerning the use of homeopathy, while in others, licenses or degrees in conventional medicine from accredited universities are required. In Germany, no specific regulations exist, while France, Austria and Denmark mandate licenses to diagnose any illness or dispense of any product whose purpose is to treat any illness.[10] Some homeopathic treatment is covered by the public health service of several European countries, including France, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Luxembourg. In other countries, such as Belgium, homeopathy is not covered. In Austria, the public health service requires scientific proof of effectiveness in order to reimburse medical treatments and homeopathy is listed as not reimbursable[168] but exceptions can be made; private health insurance policies sometimes include homeopathic treatment.[10][169] Two countries which formerly offered homeopathy under their public health services have withdrawn this privilege. At the start of 2004, homeopathic medications, with some exceptions, were no longer covered by the German public health service, and in June 2005, the Swiss Government, after a 5-year trial, withdrew homeopathy and four other complementary treatments, stating that they did not meet efficacy and cost-effectiveness criteria, though insurance can be bought to cover such treatments provided by a medical doctor.[citation needed]

See also

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- List of homeopathic preparations

- Homeopathic dilutions

- Electrohomeopathy

Notes and references

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ a b c "Dynamization and Dilution". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ Hahnemann Samuel, Organon of medicine, aphorism 217

- ^

Hahnemann, Samuel; Devrient, Charles H.; Stratten, Samuel (tr.) (1833). The Hœmeopathic Medical Doctrine, or Organon of the healing art. OCLC 32732625.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|original_language=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|original_title=ignored (help) aphorism 5 - ^ a b "Zicam Settlement". Online Lawyer Source. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ a b

Chakraborti, D; Mukherjee, SC; Saha, KC; Chowdhury, UK; et al. (2003). "Arsenic toxicity from homeopathic treatment". Clinical Toxicology. 47 (1): 963–967. doi:10.1081/CLT-120026518.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ernst E, White AR (1995). "Homoeopathy and immunization". The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 45 (400): 629–630. PMID 8554846. Cite error: The named reference "pmid8554846" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Jones, Meirion (2006-07-14). "Malaria advice 'risks lives'". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ a b c

"Critical review of The Science of Homeopathy". British Homoeopathic Journal. 67 (4). 1978.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine: A worldwide review" (PDF). World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 2001. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ a b c Ernst E (2002). "A systematic review of systematic reviews of homeopathy". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 54 (6): 577–82. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01699.x. PMID 12492603. Cite error: The named reference "pmid12492603" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Homeopathy results". National Health Service. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ a b c "Report 12 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A–97)". American Medical Association. June 1997. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ a b c

Altunç U, Pittler MH, Ernst E (2007). "Homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments: systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Mayo Clin Proc. 82 (1): 69–75. doi:10.4065/82.1.69. PMID 17285788.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Adler Jerry (4 February 2008). "No way to treat the dying". Newsweek.

- ^ a b c

Shang A, Huwiler-Müntener K, Nartey L; et al. (2005). "Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy". Lancet. 366 (9487): 726–732. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67177-2. PMID 16125589.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ernst E (2005). "Is homeopathy a clinically valuable approach?". Trends Pharmacol Sci. 26 (11): 547–8. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.003. PMID 16165225.

- ^ a b "When to believe the unbelievable". Nature. 333 (30): 787. 1988. doi:10.1038/333787a0.

- ^ a b Toufexis Anastasia (25 September 1995). "Is homeopathy good medicine?". Time. p. 2. Retrieved 2008-04-20.(page numbering given from online version)

- ^ a b

Linde; et al. (1999,). "Impact of study quality on outcome in placebo-controlled trials of homeopathy". J Clin Epidemiol. 52 (7): 631–636. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00048-7.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c

Linde K, Jonas WB, Melchart D, Willich S (2001). "The methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of homeopathy, herbal medicines and acupuncture". Int J Epidemiol. 30 (3): 526–531. doi:10.1093/ije/30.3.526. PMID 11416076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

National Science Board (2002). "Science and engineering indicators". Arlington, Virginia: National Science Foundation Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|chapter_title=ignored (|chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|section_title=ignored (help) - ^ a b Wahlberg A (2007). "A quackery with a difference—New medical pluralism and the problem of 'dangerous practitioners' in the United Kingdom". Social Science & Medicine. 65 (11): 2307–2316. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.024. PMID 17719708.

- ^ a b

Atwood KC (2003). "'Neurocranial Restructuring' and Homeopathy, Neither Complementary nor Alternative". Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 129 (12): 1356–7. doi:10.1001/archotol.129.12.1356. PMID 14676179.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Template:Harvard reference page 18

- ^ Griffin JP (2004). "Venetian treacle and the foundation of medicines regulation". Br J of Clin Pharmacol. 58 (3): 317. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02147.x.

- ^

"Blood-letting". British Medical Journal: 283. 18 March 1871.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|pmcid=ignored (|pmc=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Kaufman, Martin (1 October 1971). Homeopathy in America: The rise and fall of a medical heresy. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801812385.

- ^ Wright, Iaian. "Shakespeare and Queens' (Part II)". Queens' College Cambridge. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ a b

Lasagna, Louis (1970). The doctors' dilemmas. New York: Collier Books. p. 33. ISBN 9780836916690.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|original-year=ignored (help) - ^

Nicholls, Philip A. (1988). Homeopathy and the Medical Profession. Croom Helm. ISBN 9780709918363.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hahnemann, Samuel (1818). Organon of medicine. Leipzig.

- ^ Baxter AG (2001). "Louis Pasteur's beer of revenge". Nat Rev Immunol. 1 (3): 229–32. doi:10.1038/35105083. PMID 11905832.

- ^ Coley NG (2004). "Medical chemists and the origins of clinical chemistry in Britain (circa 1750–1850)". Clin Chem. 50 (5): 961–72. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2003.029645. PMID 15105362.

- ^ Ramberg PJ (2000). "The death of vitalism and the birth of organic chemistry: Wohler's urea synthesis and the disciplinary identity of organic chemistry". Ambix. 47 (3): 170–95. PMID 11640223.

- ^ Bradford Thomas Lindsley (1895). "35". The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann. Philadelphia: Boericke & Tafel. OCLC 1489955.

- ^ a b c d e f g "History of Homeopathy". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^

"History of Homoeopathy". Retrieved 2008-08-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Emmans Dean, Michael (2001). "Homeopathy and "the progress of science"" (PDF). History of science; an annual review of literature, research and teaching. 39 (125 Pt 3): 255–83. PMID 11712570.

- ^ a b "Homeopathic Provings". Creighton University School of Medicine. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ^

Kirschmann, Anne Taylor (2003). A Vital Force: Women in American Homeopathy. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813533209.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Samuel Hahnemann. "Organon of Medicine" (combined 5th/6th edition ed.).

{{cite web}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Winston, Julian (2006). "Homeopathy Timeline". The Faces of Homoeopathy. Whole Health Now. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Ernst E, Kaptchuk TJ (1996). "Homeopathy revisited". Arch Intern Med. 156 (19): 2162–4. doi:10.1001/archinte.156.19.2162. PMID 8885813.

- ^ John Forbes (1846). Homeopathy, allopathy and young physic. London.

- ^ James Y Simpson (1853). Homoeopathy, its tenets and tendencies, theoretical, theological and therapeutical. Edinburgh: Sutherland & Knox. p. 11.

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell (1842). Homœopathy, and its Kindred Delusions; two lectures delivered before the Boston society for the diffusion of useful knowledge. Boston: William D. Ticknor. OCLC 166600876.

- ^ Allen, J Adams, ed. (1867). "Homœopathists vs homœopathy". Chicago Medical Journal. 24: 268–269.

- ^ Homeopathic Hassle, Time, 20 August 1956

- ^ Rader William M. (March 1985), Riding the coattails of homeopathy's revival, FDA Consumer Magazine

- ^

Jonas Wayne B, Kaptchuk Ted J, Linde Klaus (4 April 2003), "A critical overview of homeopathy", Annals of Internal Medicine, 138 (5): 393–399, PMID 12614092

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ von Reiswitz F, Dinges M (2008), "Homeopathy and hospitals in history. Conference of the International Network for the History of Homeopathy (INHH) - Stuttgart, 4th to 6th July 2007" (PDF), Homoeopathic Links, 21 (1), Betalingen: 50, doi:10.1055/s-2007-989212

- ^ Winnick Terri A (February 2005), "From quackery to complementary medicine: The American medical profession confronts alternative therapies", Social Problems, 52 (1): 38–61, doi:10.1525/sp.2005.52.1.38

- ^ O'Hara Mary (5 January 2002), A question of health or wealth?, The Guardian

- ^ Winston, Julian. "Outline of the Organon". Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Hahnemann, Samuel. "Organon Of Medicine". Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Little David. "The classical view on miasms". Homeopathy Online. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- ^

The chronic diseases, their nature and homoeopathic treatment. Dresden and Leipsic: Arnold.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|volumes=ignored (help) - ^ Hahnemann Samuel. "Organon" (5th edition, para 29 ed.). HomeopathyHome.com. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ a b "Miasms in homeopathy". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Ward JW. "Taking the History of the Case". Pacific Coast Jnl of Homeopathy, July 1937. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ "Cause of Disease in homeopathy". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ a b Birnbaum NR, Goldschmidt RH, Buffett WO (1999). "Resolving the common clinical dilemmas of syphilis". American family physician. 59 (8): 2233–40, 2245–6. PMID 10221308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Online Museum". The Institute for the History of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ a b

Williams Nathan (26 November 2002). "Homeopathy: The test". Horizon (BBC). Retrieved 2007-01–26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) (transcript) - ^ In standard chemistry, this produces a substance with a concentration of 0.01%, measured by the volume-volume percentage method.

- ^ "Glossary of Homeopathic Terms". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Smith, Trevor. Homeopathic Medicine Healing Arts Press, 1989. 14–15

- ^ "Similia similibus curentur (Like cures like)". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ "Arsenic in drinking water". United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- ^ a b Hahnemann. "Organon of medicine". aphorism 128

- ^ a b c For further discussion of homeopathic dilutions and the mathematics involved, see Homeopathic dilutions.

- ^ a b Bambridge AD (1989). Homeopathy investigated. Kent, England: Diasozo Trust. ISBN 0-94817120-0.

- ^ a b Andrews Peter (1990). "Homeopathy and Hinduism". The Watchman Expositor.

- ^

Pouring a 1 liter bottle of poison into Lake Geneva would only result in about a 7C remedy, since Lake Geneva has a volume of about 89 cubic kilometers of water (

Anneville Orlane, Souissi Sami, Ibanez Frederic, Ginot Vincent, Druart Jean Claude, Angeli Nadine (2002). "Temporal mapping of phytoplankton assemblages in Lake Geneva: Annual and interannual changes in their patterns of succession". Limnology and Oceanography. 47 (5): 1355–1366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)) - ^ A 12C solution produced using sodium chloride (also called natrum muriaticum in homeopathy) is the equivalent of dissolving 0.36 mL of table salt, weighing about 0.77 g, into a volume of water the size of the Atlantic Ocean, since the volume of the Atlantic Ocean and its adjacent seas is 3.55×108 km3 or 3.55×1020 L : Emery Kenneth Orris, Uchupi Elazar (1984). The geology of the Atlantic Ocean. Springer. ISBN 0-38796032-5.

- ^ The volume of all water on earth is about 1.36×109 km3: "Earth's water distribution". Water Science for Schools. United States Geological Survey. 28 August 2006.

- ^ Gleick PH, Water resources, In

Schneider SH (ed) (1996). Encyclopedia of climate and weather. Vol. 2. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 817–823.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)). - ^ Robert, Ellis Dudgeon (1853). Lectures on the theory & practice of homeopathy (PDF). London: B. Jain. pp. 526–7. ISBN 81-7021-311-8.

- ^ Little, David. "Hahnemann's advanced methods". Simillimum.com. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ If a dilution is designated as q on the Q scale, and c on the C scale, c/q=log10(50,000)/2=2.349485.

- ^ Edwin Wheeler, Charles (1941). Dr. Hughes: Recollections of some masters of homeopathy. Health through homeopathy.

- ^ Bodman, Frank (1970). The Richard Hughes memorial lecture. BHJ. pp. 179–193.

- ^ "ConsumerReports.org - HeadOn: Headache drug lacks clinical data". Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ "Analysis of Head On". James Randi's Swift. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

- ^ Stossel John (2008). "Homeopathic remedies – can water really remember?". 20/20. ABC News. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^

Dantas F, Fisher P, Walach H; et al. (2007). "A systematic review of the quality of homeopathic pathogenetic trials published from 1945 to 1995". Homeopathy : the journal of the faculty of homeopathy. 96 (1): 4–16. PMID 17227742.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kayne, S. B. and Caldwell, I. M. (2006). Homeopathic pharmacy: theory and practice. 2nd Ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, p.52

- ^

Cassedy, James H. (1999). American Medicine and Statistical Thinking, 1800–1860. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-58348428-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fye WB (1986). "Nitroglycerin: a homeopathic remedy" (PDF). Circulation. 73 (1): 21–9. PMID 2866851.

- ^

Samuel Hahnemann; et al. (1826–1828). Materia medica pura; sive, Doctrina de medicamentorum viribus in corpore humano sano observatis; e Germanico sermone in Latinum conversa (in Latin). Dresden: Arnold. OCLC 14840659.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^

von Bönninghausen Clemens, Bradford TL, Boger CM. (1999, Reprint Ed.). Boenninghausen's characteristics and repertory with word index. New Delhi: B. Jain. ISBN 8-170-21207-3.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

Bellavite P, Conforti A, Piasere V, Ortolani R (2005). "Immunology and homeopathy. 1. Historical background". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2 (4): 441–52. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh141. PMID 16322800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Stehlin Isadora (1996). "Homeopathy: Real medicine or empty promises?". US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b

Jonas WB, Kaptchuk TJ, Linde K (2003). "A critical overview of homeopathy". Ann Intern Med. 138 (5): 393–399. doi:10.1001/archinte.138.3.393. PMID 12614092.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones, Kathryn. "Materia medica: remedy information". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^

Bellavite P, Conforti A, Piasere V, Ortolani R (2005). "Immunology and homeopathy. 1. Historical background". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2 (4): 441–52. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh141. PMID 16322800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Norland Misha (1998). "The homœopathic proving of positronium". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Clarke John Henry (1902). A Dictionary of Practical Materia Medica. London: Homeopathic Publishing. OCLC 11081023.

- ^ English, Mary. "The homeopathic proving of 'Tempesta' the storm". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Doheny, Kathleen. "Homeopathy: natural approach or all a fake?". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Shah, Rajesh. "Call for introspection and awakening" (PDF). Life Force Center. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Barwell, Bruce. "Homoeopathica: The wo-wo effect". New Zealand Homoeopathic Society. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ "Isopathy". Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ van Haselen RA (1999). "The relationship between homeopathy and the Dr Bach system of flower remedies: a critical appraisal". The British homoeopathic journal. 88 (3): 121–7. doi:10.1054/homp.1999.0308. PMID 10449052.

- ^ Ernst E (2002). ""Flower remedies": a systematic review of the clinical evidence". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 114 (23–24): 963–6. PMID 12635462.

- ^ Saxton JG (2007). "The diversity of veterinary homeopathy". Homeopathy. 96 (1): 3. doi:10.1016/j.homp.2006.11.010. PMID 17227741.

- ^ "The American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association". Retrieved 2008-10-04.[dubious ]

- ^ a b Hektoen L (2005). "Review of the current involvement of homeopathy in veterinary practice and research". Vet Rec. 157 (8): 224–9. PMID 16113167.

- ^ a b Teixeira J (2007). "Can water possibly have a memory? A sceptical view". Homeopathy : the journal of the Faculty of Homeopathy. 96 (3): 158–162. doi:10.1016/j.homp.2007.05.001.

- ^ a b

Milgrom LR (2007). "Conspicuous by its absence: the Memory of Water, macro-entanglement, and the possibility of homeopathy". Homeopathy. 96 (3): 209–19. doi:10.1016/j.homp.2007.05.002. PMID 17678819.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b

Levy G (1986). "Kinetics of drug action: an overview". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 78 (4 Pt 2): 754–61. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(86)90057-6. PMID 3534056.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Barrett, Stephen (28 December 2004). "Homeopathy: the ultimate fake". Quackwatch. Quackwatch. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ Ernst E (2007). "Placebo: new insights into an old enigma". Drug Discov Today. 12 (9–10): 413–8. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2007.03.007. PMID 17467578.

- ^

Ndububa VI (2007). "Medical quackery in Nigeria; why the silence?". Niger J Med. 16 (4): 312–317. PMID 18080586.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ernst E, Pittler MH (1998). "Efficacy of homeopathic arnica: a systematic review of placebo-controlled clinical trials". Arch Surg. 133 (11): 1187–90. doi:10.1001/archsurg.133.11.1187. PMID 9820349.

- ^

Teixeira1 J, Luzar A, Longeville S (2006). "Dynamics of hydrogen bonds: how to probe their role in the unusual properties of liquid water". J Phys Condens Matter. 18: S2353–S2362. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/36/S09.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

Weissmann G (2006). "Homeopathy: Holmes, Hogwarts, and the Prince of Wales". Faseb J. 20 (11): 1755–8. doi:10.1096/fj.06-0901ufm. PMID 16940145.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Horizon's homeopathic coup, Cuzco's altitude, more funny sites, the clangers, overdue, Orbito nabbed in Padua, Randi a zombie?, Stellar guests at amazing meeting, and great new Shermer books!". Swift, Online Newsletter of the JREF. James Randi Educational Foundation. 29 November 2002. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ^

Boyd WA, Williams PL (2003). "Comparison of the sensitivity of three nematode species to copper and their utility in aquatic and soil toxicity tests". Environ Toxicol Chem. 22 (11): 2768–74. doi:10.1897/02-573. PMID 14587920.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Goldoni M, Vettori MV, Alinovi R, Caglieri A, Ceccatelli S, Mutti A (2003). "Models of neurotoxicity: extrapolation of benchmark doses in vitro". Risk Anal. 23 (3): 505–14. doi:10.1111/1539-6924.00331. PMID 12836843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Yu HS, Liao WT, Chai CY (2006). "Arsenic carcinogenesis in the skin". J Biomed Sci. 13 (5): 657–66. doi:10.1007/s11373-006-9092-8. PMID 16807664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stephen Barrett. "Homeopathy - The Ultimate Fake". newsletter of the Rational Examination Association of Lincoln Land (REALL).

- ^ "Dynamization and dilution". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ "Questions and answers about homeopathy". US National Institute of Health (NCCAM research report). Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ^ Atmanspacher, H., Romer, H., Walach, H. (2002): Weak Quantum Theory: Complementarity and Entanglement in Physics and Beyond. Foundations of Physics, Volume 32, Number 3, March 2002 , pp. 379-406(28)

- ^

Walach H, Jonas WB, Ives J, van Wijk R, Weingärtner O (2005). "Research on homeopathy: state of the art". J Altern Complement Med. 11 (5): 813–29. doi:10.1089/acm.2005.11.813. PMID 16296915.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Reilly DT, Taylor MA, McSharry C, Aitchison T (1986). "Is homoeopathy a placebo response? Controlled trial of homoeopathic potency, with pollen in hayfever as model". Lancet. 2 (8512): 881–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90410-1. PMID 2876326.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Taylor MA, Reilly D, Llewellyn-Jones RH, McSharry C, Aitchison TC (2000). "Randomised controlled trial of homoeopathy versus placebo in perennial allergic rhinitis with overview of four trial series". BMJ. 321 (7259): 471–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7259.471. PMID 10948025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Brien S, Lewith G, Bryant T (2003). "Ultramolecular homeopathy has no observable clinical effects. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proving trial of Belladonna 30C". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 56 (5): 562–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01900.x. PMID 14651731.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Lewith GT, Watkins AD, Hyland ME; et al. (2002). "Use of ultramolecular potencies of allergen to treat asthmatic people allergic to house dust mite: double blind randomised controlled clinical trial". BMJ. 324 (7336): 520. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7336.520. PMID 11872551.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Report on mustard gas experiments". British Homoeopathic Journal. 33. British Homoeopathic Society: 1–12. 1943.

- ^

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P, ter Riet G (1991). "Clinical trials of homoeopathy". BMJ. 302 (6772): 316–323. PMID 1825800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

Linde K, Clausius N, Ramirez G; et al. (1997). "Are the clinical effects of homeopathy placebo effects? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials". Lancet. 350 (9081): 834–43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02293-9. PMID 9310601.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b

Caulfield T, Debow S (2005), "A systematic review of how homeopathy is represented in conventional and CAM peer reviewed journals", BMC Complement Altern Med, 5: 12, doi:10.1186/1472-6882-5-12, PMID 15955254

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^

Milazzo S, Russell N, Ernst E (2006). "Efficacy of homeopathic therapy in cancer treatment". Eur J Cancer. 42 (3): 282–289. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.09.025. PMID 16376071.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

McCarney RW, Linde K, Lasserson TJ (2004). "Homeopathy for chronic asthma". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000353. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000353.pub2. PMID 14973954.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

McCarney R, Warner J, Fisher P, Van Haselen R (2003). "Homeopathy for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003803. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003803. PMID 12535487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith CA (2003). "Homoeopathy for induction of labour". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003399. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003399. PMID 14583972.

- ^ Long L, Ernst E (2001). "Homeopathic remedies for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review". The British homoeopathic journal. 90 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1054/homp.1999.0449. PMID 11212088.

- ^

Whitmarsh TE, Coleston-Shields DM, Steiner TJ (1997). "Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of homoeopathic prophylaxis of migraine". Cephalalgia. 17 (5): 600–604. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1705600.x. PMID 9251877.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Homeopathy results". National Health Service. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ Vithoulkas George. "Another point of view for the homeopathic trials and meta-analyses".

- ^ "Homoeopathy's benefit questioned". BBC News. 26 August 2005. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ Linde Klaus, Melchart Dieter (1 December 1998). "Randomized controlled trials of individualized homeopathy: A state-of-the-art review". J Altern Complement Med. 4 (4): 371–388. doi:10.1089/acm.1998.4.371. PMID 9884175.

- ^

Kolisko Lilly (1959). [Physiological and physical evidence of the effectiveness of the smallest entities] Physiologischer und physikalischer Nachweis der Wirksamkeit kleinster Entitäten (in German). Stuttgart.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nlmid=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Junker H (1925). Biologisches Zentralblatt. 45 (1): 26.{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) and Pflügers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 219 (B). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer: 5–6. 1928. eISSN 1432-2013. ISSN 0031-6768.{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^

Wälchli C, Baumgartner S, Bastide M (2006). "Effect of low doses and high homeopathic potencies in normal and cancerous human lymphocytes: an in vitro isopathic study". J Altern Complement Med. 12 (5). New York: 421–7. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.421. PMID 16813505.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Walach H, Köster H, Hennig T, Haag G (2001). "The effects of homeopathic belladonna 30CH in healthy volunteers — a randomized, double-blind experiment". J Psychosom Res. 50 (3): 155–60. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00224-5. PMID 11316508.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Hirst SJ, Hayes NA, Burridge J, Pearce FL, Foreman JC (1993). "Human basophil degranulation is not triggered by very dilute antiserum against human IgE". Nature. 366 (6455): 525–7. doi:10.1038/366525a0. PMID 8255290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Ovelgönne JH, Bol AW, Hop WC, van Wijk R (1992). "Mechanical agitation of very dilute antiserum against IgE has no effect on basophil staining properties". Experientia. 48 (5): 504–8. doi:10.1007/BF01928175. PMID 1376282.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Witt CM, Bluth M, Hinderlich S; et al. (2006). "Does potentized HgCl2 (Mercurius corrosivus) affect the activity of diastase and alpha-amylase?". J Altern Complement Med. 12 (4). New York: 359–65. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.359. PMID 16722785.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Guggisberg AG, Baumgartner SM, Tschopp CM, Heusser P (2005). "Replication study concerning the effects of homeopathic dilutions of histamine on human basophil degranulation in vitro". Complement Ther Med. 13 (2): 91–100. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2005.04.003. PMID 16036166.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Maddox, John (1988-07-28). "'High-dilution' experiments a delusion" (PDF). Nature. 334: 287–90. doi:10.1038/334287a0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sullivan, Walter (1988-07-27). "Water That Has a Memory? Skeptics Win Second Round". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Beneveniste defended his results, however, comparing the inquiry to the Salem witch hunts and asserting that "It may be that all of us are wrong in good faith. This is no crime but science as usual and only the future knows."

- ^ "Zicam Marketers Sued". Homeowatch.org. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ Boodman, Sandra (31 January 2006). "Paying through the nose". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ Ernst E (1997). "The attitude against immunisation within some branches of complementary medicine". Eur. J. Pediatr. 156 (7): 513–5. doi:10.1007/s004310050650. PMID 9243229.

- ^ Ernst E (2001). "Rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine: reasons and consequences for vaccination". Vaccine. 20 Suppl 1: S90–3, discussion S89. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00290-0. PMID 11587822.

- ^

Pray, W.S. (1992). "A challenge to the credibility of homeopathy". Am. J. Pain Mangmnt., (2): 63–71.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^

English, John (1992). "The issue of immunization". British Homoeopathic journal. 81 (4): 161–3. doi:10.1016/S0007-0785(05)80171-1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Jha, Alok (2006-07-14). "Homeopaths 'endangering lives' by offering malaria remedies". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ a b

Delaunay P, Cua E, Lucas P, Marty P (2000). "Homoeopathy may not be effective in preventing malaria". BMJ. 321 (7271): 1288. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1288. PMID 11082104.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bunyan, Nigel (2007-03-22). "Patient died after being told to stop heart medicine". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^

"Fitness To Practise panel hearing on Dr Marisa Viegas". General Medical Council. 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pray WS (2006). "Ethical, scientific, and educational concerns with unproven medications". American journal of pharmaceutical education. 70 (6): 141. PMID 17332867.

- ^ Ian Sample (2008-07-21). "Pharmacists urged to 'tell the truth' about homeopathic remedies". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ^

Hauptverband der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger (31 March 2004). "Liste nicht erstattungsfähiger Arzneimittelkategorien gemäß § 351c Abs. 2 ASVG (List of treatments not reimbursable by social service providers in [[Austria]]) [[:Template:De icon]]".

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dr. Dietmar G* vs. Salzburger Gebietskrankenkasse, 10ObS46/08z (Reimbursement of homeopathic treatment on medical grounds) Template:De icon (Oberster Gerichtshof OGH - Austrian supreme court 24 July 2008).

External links

Associations and regulatory bodies

- British Homeopathic Association (BHA)

- European Committee for Homeopathy (ECH)

- European Council for Classical Homeopathy (ECCH)

- Homeopathic Pharmacopeia Convention of the United States (HPCUS)

- National Center for Homeopathy (NCH)

Other links

- "Homeopathy: real medicine or empty promises?". FDA Consumer Magazine. US Food and Drug Administration. 1996. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Questions and answers about homeopathy". National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). 2003. Retrieved 9 January 2009.