Kombucha: Difference between revisions

Bon courage (talk | contribs) →Health claims: add |

Bon courage (talk | contribs) →top: per Tyler's suggestion on talk (excep using "linked to" rather than "associated with" to avoid potential copy/paste problem with source); sync with body/new source |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Kombucha Mature.jpg|thumb|225px|Kombucha including the culture]] |

[[Image:Kombucha Mature.jpg|thumb|225px|Kombucha including the culture]] |

||

'''Kombucha''' (Russian: chaynyy grib (чайный гриб), Chinese: chájūn (茶菌), Korean: hongchabeoseotcha (홍차버섯차), Japanese: kōcha-kinoko (紅茶キノコ)), is a lightly [[effervescent]] [[Fermentation (food)|fermented drink]] of sweetened [[black tea|black]] and/or [[green tea|green]] tea that is used as a [[functional food]]. It is produced by fermenting the tea using a [[SCOBY|symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast]] (SCOBY). Although kombucha is claimed to have several beneficial effects on health, the claims are not supported by scientific evidence |

'''Kombucha''' (Russian: chaynyy grib (чайный гриб), Chinese: chájūn (茶菌), Korean: hongchabeoseotcha (홍차버섯차), Japanese: kōcha-kinoko (紅茶キノコ)), is a lightly [[effervescent]] [[Fermentation (food)|fermented drink]] of sweetened [[black tea|black]] and/or [[green tea|green]] tea that is used as a [[functional food]]. It is produced by fermenting the tea using a [[SCOBY|symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast]] (SCOBY). Although kombucha is claimed to have several beneficial effects on health, the claims are not supported by scientific evidence,<ref name=acs/> and the drinking kombucha has been linked to illness and death.<ref name=Dasgupta2011/><ref name=pfp/> |

||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

Revision as of 13:28, 10 June 2015

Kombucha (Russian: chaynyy grib (чайный гриб), Chinese: chájūn (茶菌), Korean: hongchabeoseotcha (홍차버섯차), Japanese: kōcha-kinoko (紅茶キノコ)), is a lightly effervescent fermented drink of sweetened black and/or green tea that is used as a functional food. It is produced by fermenting the tea using a symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY). Although kombucha is claimed to have several beneficial effects on health, the claims are not supported by scientific evidence,[1] and the drinking kombucha has been linked to illness and death.[2][3]

Etymology

In Japan, Konbucha (昆布茶, "kelp tea") refers to a different beverage made from dried and powdered kombu (an edible kelp from the Laminariaceae family).[4] For the origin of the English word kombucha, in use since at least 1991[5] and of uncertain etymology,[6] the American Heritage Dictionary suggests: "Probably from Japanese kombucha, tea made from kombu (the Japanese word for kelp perhaps being used by English speakers to designate fermented tea due to confusion or because the thick gelatinous film produced by the kombucha culture was thought to resemble seaweed)."[7]

The Japanese name for what English speakers know as kombucha is kōcha kinoko 紅茶キノコ (literally, 'black tea mushroom'), compounding kōcha "black tea" and kinoko 茸 "mushroom; toadstool". The Chinese names for kombucha are hóngchájùn 红茶菌 ('red tea fungus'), cháméijūn 茶黴菌 ('tea mold'), or hóngchágū 红茶菇 ('red tea mushroom'), with jūn 菌 'fungus, bacterium or germ' (or jùn 'mushroom'), méijūn 黴菌 'mold or fungus', and gū 菇 'mushroom'. ("Red tea", 紅茶, in Chinese languages corresponds to English "black tea".)

A 1965 mycological study called kombucha "tea fungus" and listed other names: "teeschwamm, Japanese or Indonesian tea fungus, kombucha, wunderpilz, hongo, cajnij, fungus japonicus, and teekwass".[8] Some further spellings and synonyms include combucha and tschambucco, and haipao, kargasok tea, kwassan, Manchurian fungus or mushroom, spumonto, as well as the misnomers champagne of life, and chai from the sea.[9][clarification needed]

History

Kombucha most likely originated in Northeast China or Manchuria later spreading to east Russia sometime before 1910 and from there, to Europe.[10] In Russian, the kombucha culture is called chainyy grib чайный гриб (literally "tea fungus/mushroom"), and the fermented drink is called chainyy grib, grib ("fungus; mushroom"), or chainyy kvas чайный квас ("tea kvass"). Kombucha was highly popular and seen as a health food in China in the 1950s and 1960s. Many families grew kombucha at home.[citation needed] No historical records show use in ancient China or Japan (see history of tea in China and history of tea in Japan).[citation needed] NBC News has reported that the drink is 2,000 years old.[11]

Kombucha's English name is derived from Japanese. According to folklore, it was introduced to Japan by a Korean doctor named Kombu as a health tonic.[11]

Chemical and biological properties

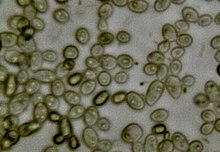

A kombucha culture is a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY), containing Acetobacter (a genus of acetic acid bacteria) and one or more yeasts, which form a zoogleal mat. In Chinese, the microbial culture is called haomo in Cantonese, or jiaomu in Mandarin, (Chinese: 酵母; lit. 'fermentation mother'). It is also known as Manchurian Mushroom.

Kombucha cultures may contain one or more of the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Brettanomyces bruxellensis, Candida stellata, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Torulaspora delbrueckii, and Zygosaccharomyces bailii. Alcohol production by the yeast(s) contributes to the production of acetic acid by the bacteria.[citation needed]

Although the bacterial component of a kombucha culture comprises several species, it almost always includes Gluconacetobacter xylinus (formerly Acetobacter xylinum), which ferments the alcohol(s) produced by the yeast(s) into acetic acid, increasing the acidity while limiting the kombucha's alcoholic content. The number of bacteria and yeasts that were found to produce acetic acid increased for the first four days of fermentation, decreasing thereafter. Sucrose gets broken down into fructose and glucose, and the bacteria and yeast convert the glucose and fructose into gluconic acid and acetic acid, respectively.[10] G. xylinum is responsible for most or all of the physical structure of a kombucha mother, and has been shown to produce microbial cellulose,[12] likely due to selection over time for firmer and more robust cultures by brewers.

The acidity and mild alcoholic element of kombucha resists contamination by most airborne molds or bacterial spores. A study showed that kombucha inhibits growth of harmful microorganisms such as E. coli, Sal. enteritidis, Sal. typhimurium, and Sh. sonnei.[10] As a result, kombucha is relatively easy to maintain as a culture outside of sterile conditions. The bacteria and yeasts in kombucha promoted microbial growth for the first six days of fermentation; after that, they steadily declined. Kombucha retained its antimicrobial capability even after being heated, and at a pH of 7. While the beverage inhibited growth of certain bacteria, it had no effect on the yeasts. The study also found that large proteins and catechins such as Epigallocatechin gallate also contributed to the antimicrobial properties of kombucha.[10]

Kombucha culture can also be used to make artificial leather, for example London based fashion designer Suzanne Lee is experimenting with creating jackets and shoes. [13]

Kombucha contains multiple species of yeast and bacteria along with the organic acids, active enzymes, amino acids, and polyphenols they produce. The exact quantities vary between samples, but may contain: acetic acid, ethanol, gluconic acid, glucuronic acid, glycerol, lactic acid, usnic acid and B-vitamins.[14][15][16] It was also found that kombucha contains about 1.51 mg/mL of vitamin C.[17]

According to the American Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, many kombucha products contain more than 0.5% alcohol by volume, but some contain less.[18]

Reports of adverse reactions may be related to unsanitary fermentation conditions, leaching of compounds from the fermentation vessels, or "sickly" kombucha cultures that cannot acidify the brew.[19]

Health claims

According to the American Cancer Society, "Kombucha tea has been promoted as a cure-all for a wide range of conditions including baldness, insomnia, intestinal disorders, arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, AIDS, and cancer. Supporters say that Kombucha tea can boost the immune system and reverse the aging process."[1] The consumption of Kombucha can cause liver damage, and has been associated with other illness and fatality.[2][3] Although laboratory experiments are suggestive of possible health effects, there is no evidence that kombucha consumption benefits human health.[20][21][22]

Case reports "raise doubts about the safety of kombucha",[22] since there have been incidents of central nervous system impairment, suspected liver damage, metabolic acidosis,[22] and toxicity in general.[22][23] Acute conditions caused by drinking of kombucha, such as lactic acidosis, are more likely to occur in persons with pre-existing medical conditions.[23] Other reports suggest exercising caution if regularly drinking kombucha while taking medical drugs or hormone replacement therapy.[24] Kombucha may also cause allergic reactions.[25] Some adverse health effects may be due to the acidity of the tea, cautioning preparers to avoid over-fermentation.[26]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Kombucha Tea". American Cancer Society. 21 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2015-06-07. Retrieved January 2015.

Available scientific evidence does not support claims that Kombucha tea promotes good health, prevents any ailments, or works to treat cancer or any other disease. Serious side effects and occasional deaths have been linked with drinking Kombucha tea.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Dasgupta A (2011). Chapter 11: Toxic and Dangerous Herbs. Walter de Gruyter. p. 111. ISBN 978-3-11-024561-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bryant BJ, Knights KM (2011). Chapter 3: Over-the-counter Drugs and Complementary Therapies (3rd ed.). Elsevier Australia KM. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7295-3929-6.

Kombucha has been associated with illnesses and death. A tea made from Kombucha is said to be a tonic, but several people have been hospitalised and at least one woman died after taking this product.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Wong, Crystal. U.S. 'kombucha': Smelly and No Kelp, The Japan Times. July 12, 2007.

- ^ The New York Times "A Magic Mushroom Or a Toxic Fad?"

- ^ Algeo, John; Algeo, Adele (1997). "Among the New Words". American Speech. 72 (2): 183–97. doi:10.2307/455789. JSTOR 455789.

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary, 4th ed. 2000, updated 2009, Houghton Mifflin Company. kombucha, TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ Hesseltine, C. W. (1965). "A Millennium of Fungi, Food, and Fermentation". Mycologia. 57 (2): 149–97. doi:10.2307/3756821. JSTOR 3756821. PMID 14261924.

- ^ Kombucha, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

- ^ a b c d Sreeramulu, G; Zhu, Y; Knol, W (2000). "Kombucha fermentation and its antimicrobial activity". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (6): 2589–94. doi:10.1021/jf991333m. PMID 10888589.

- ^ a b Helm, Janet. "Trendy Fizzy Drink is Mushrooming". NBC News. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Nguyen, VT; Flanagan, B; Gidley, MJ; Dykes, GA (2008). "Characterization of cellulose production by a gluconacetobacter xylinus strain from kombucha". Current Microbiology. 57 (5): 449–53. doi:10.1007/s00284-008-9228-3. PMID 18704575.

- ^ "Suzanne Lee: Grow your own clothes". TED2011. March 2011.

- ^ Teoh, AL; Heard, G; Cox, J (2004). "Yeast ecology of kombucha fermentation". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 95 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020. PMID 15282124.

- ^ Dufresne, C; Farnworth, E (2000). "Tea, kombucha, and health: A review". Food Research International. 33 (6): 409. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3.

- ^ Velicanski, A; Cvetkovic, D; Markov, S; Tumbas, V; Savatovic, S (2007). "Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of lemon balm Kombucha". Acta Periodica Technologica (38): 165–72. doi:10.2298/APT0738165V.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Bauer-Petrovska, B; Petrushevska-Tozi, L (2000). "Mineral and water soluble vitamin content in the kombucha drink". International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 35 (2): 201–5. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2621.2000.00342.x.

- ^ "Kombucha FAQs" (PDF). Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Phan, TG; Estell, J; Duggin, G; Beer, I; Smith, D; Ferson, MJ (December 1998). "Lead poisoning from drinking kombucha tea brewed in a ceramic pot". The Medical journal of Australia. 169 (11–12): 644–6. PMID 9887919.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Jayabalan, R; Malbaša, RV; Lončar, ES; Vitas, JS; Sathishkumar, M (July 2014). "A review on kombucha tea — microbiology, composition, fermentation, beneficial effects, toxicity, and tea fungus". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 13 (4): 538–50. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12073.

There has been no evidence published to date on the biological activities of kombucha in human trials.

- ^ Vīna I, Semjonovs P, Linde R, Deniņa I (2014). "Current evidence on physiological activity and expected health effects of kombucha fermented beverage". J Med Food (Review). 17 (2): 179–88. doi:10.1089/jmf.2013.0031. PMID 24192111.

- ^ a b c d Ernst, E. (April 2003). "Kombucha: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Evidence". Forschende Komplementärmedizin und Klassische Naturheilkunde. 10 (2): 85–87. doi:10.1159/000071667. PMID 12808367.

- ^ a b Sunghee Kole, A.; Jones, H. D.; Christensen, R.; Gladstein, J. (May 2009). "A Case of Kombucha Tea Toxicity". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 24 (3): 205–07. doi:10.1177/0885066609332963. PMID 19460826.

- ^ Srinivasan, Radhika; Smolinske, Susan; Greenbaum, David (Oct 1997). "Probable Gastrointestinal Toxicity of Kombucha Tea". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 12 (10): 643–44. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07127.x. PMC 1497178. PMID 9346462.

- ^ Perron, AD; Patterson, JA; Yanofsky, NN (1995). "Kombucha 'Mushroom' Hepatotoxicity". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 26 (5): 660–61. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70028-5. PMID 7486385.

- ^ Nummer, Brian A. (2013). "Kombucha Brewing Under the Food and Drug Administration Model Food Code: Risk Analysis and Processing Guidance". Journal of Environmental Health. 76 (4).

Further reading

- Dipti, P; Yogesh, B; Kain, A. K.; Pauline, T; Anju, B; Sairam, M; Singh, B; Mongia, S. S.; Kumar, G. I.; Selvamurthy, W (September 2003). "Lead induced oxidative stress: beneficial effects of Kombucha tea". Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES. 16 (3): 276–82. PMID 14631833.

- Ernst, E (April 2003). "Kombucha: a systematic review of the clinical evidence". Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 10 (2): 85–7. doi:10.1159/000071667. PMID 12808367.

- Frank, Günther W. (1995). Kombucha: Healthy Beverage and Natural Remedy from the Far East, Its Correct Preparation and Use. Steyr: Pub. House W. Ennsthaler. ISBN 978-3-85068-337-1.

- Pauline, T; Dipti, P; Anju, B; Kavimani, S; Sharma, S. K.; Kain, A. K.; Sarada, S. K.; Sairam, M; Ilavazhagan, G; Devendra, K; Selvamurthy, W (September 2001). "Studies on toxicity, anti-stress and hepato-protective properties of Kombucha tea". Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES. 14 (3): 207–13. PMID 11723720.